Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Energy Transition

Abstract

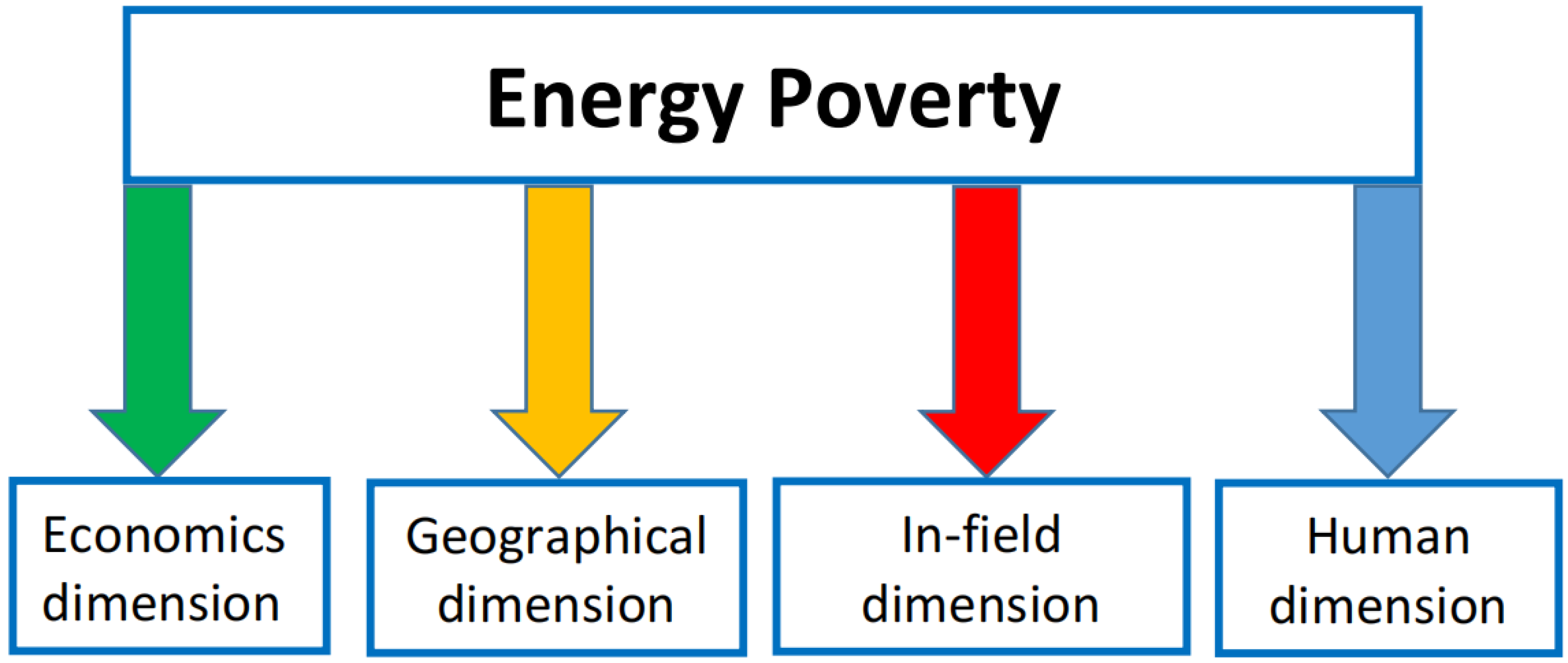

:1. Energy Poverty as a Multi-Parametric Issue: Literature Overview

- (A)

- The economic dimension, referring to energy poverty and energy vulnerability in developed and developing European countries, focuses on welfare losses, housing policies, and economic concerns. This key aspect of reviewing was further organized into the following spatial contexts of literature studies: Northern Europe, Central Europe, and Mediterranean Europe.

- (B)

- The geographical dimension, referring to the geographical context/coverage of reviewing, includes the continents of Asia (mainly China, followed by India and Pakistan) and America.

- (C)

- The in-field dimension, referring to energy poverty and large-scale spatial analyses, focuses on the regional level of analysis and typical infrastructure works involved in similar studies.

- (D)

- The human dimension, referring to energy poverty and its socio-cultural features and anthropocentric considerations, concentrates on the human adaptation and the community involvement in a global prospect of energy poverty.

2. Economic Dimension: Energy Poverty and Energy Vulnerability in Developed and Developing European Countries: Welfare Losses, Housing Policies, and Economic Concerns

3. Geographical Dimension

4. In Field Dimension: Energy Poverty and Large-Scale Spatial Analyses and Infrastructure Works

5. Human Dimension: Energy Poverty Socio-Cultural Features and Anthropocentric Considerations

6. Discussions

- -

- Controlling and regulating households’ energy consumption and the emitted huge greenhouse gases (GHG), they can potentially and positively impact energy poverty reduction, implementation of the energy justice principle, and climate change mitigation [52].

- -

- Identifying trust can be valued as an important channel through which ethnic diversity operates, shaping policies regarding social capital in multi-cultural societies and adopting feasible alternative ways to measure energy poverty [53].

- -

- By using quantitative and statistical methods, realistic longitudinal approaches can precisely record the energy efficiency measures that have been adopted in the past, interpreting energy poverty under specific socio-economic conditions and revealing that the improvement of energy efficiency in homes that are at risk of energy poverty has a profound impact on (a) the well-being and quality of life [54] and (b) exploring how the social dimension of energy poverty could be integrated into future policymaking processes [55].

- -

- Linking the utility of localized and remote renewable energy sources (RES) with better spatial planning of land uses [56,57], such as biomass production [58], enables policy makers to determine the optimal budgeting mix through relevant weights of each aspect that guarantees the success of the designed energy-oriented ventures [59].

- -

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Platten, J. Energy poverty in Sweden: Using flexibility capital to describe household vulnerability to rising energy prices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. A Systematic Literature Review of Indices for Energy Poverty Assessment: A Household Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, K.; Janzen, B. Determinants, persistence, and dynamics of energy poverty: An empirical assessment using German household survey data. Energy Econ. 2021, 102, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, K.; Seebauer, S. The energy austerity pitfall: Linking hidden energy poverty with self-restriction in household use in Austria. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat-Jarka, A.; Trębska, P.; Jarka, S. The role of renewable energy sources in alleviating energy poverty in households in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojilovska, A.; Yoon, H.; Robert, C. Out of the margins, into the light: Exploring energy poverty and household coping strategies in Austria, North Macedonia, France, and Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrella, R.; Linares, J.I.; Romero, J.C.; Arenas, E.; Centeno, E. Does cash money solve energy poverty? Assessing the impact of household heating allowances in Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boemi, S.N.; Samarentzi, M.; Dimoudi, A. Research of energy behaviour and energy poverty of households in Northern Greece. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 410, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, A.; Gouveia, J.P.; Schmidt, L.; Sousa, J.C.; Palma, P.; Simões, S. Energy poverty in Portugal: Combining vulnerability mapping with household interviews. Energy Build. 2019, 203, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dogan, E.; Madaleno, M.; Taskin, D. Which households are more energy vulnerable? Energy poverty and financial inclusion in Turkey. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Feng, C. Linking Housing Conditions and Energy Poverty: From a Perspective of Household Energy Self-Restriction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.; Hsu, C.-C.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Vu, H.M.; Nawaz, M.A. Unlocking the role of energy poverty and its impacts on financial growth of household: Is there any economic concern. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 13431–13444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Song, M.; Xie, B. Eliminating energy poverty in Chinese households: A cognitive capability framework. Renew. Energy 2022, 192, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiao, W.; Wang, K.; Li, E.; Yan, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, X. Examining the multidimensional energy poverty trap and its determinants: An empirical analysis at household and community levels in six provinces of China. Energy Policy 2022, 169, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Deng, L.; Ji, Q.; Zhai, P. Environmental regulations, clean energy access, and household energy poverty: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Chen, W.; Sun, L. Impact of energy poverty on household quality of life—Based on Chinese household survey panel data. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.-B. Who suffers from energy poverty in household energy transition? Evidence from clean heating program in rural China. Energy Econ. 2022, 106, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-P.; Zeng, W.-K.; Gong, S.-W.; Chen, Z.-G. Does Energy Poverty Reduce Rural Labor Wages? Evidence From China’s Rural Household Survey. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 670026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Li, S.; Xu, D.; Baz, K.; Rakhmetova, A. Do socioeconomic factors determine household multidimensional energy poverty? Empirical evidence from South Asia. Energy Policy 2020, 146, 111754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathen, C.K.; Sadath, A.C. Examination of energy poverty among households in Kasargod District of Kerala. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 68, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, E.; Sarangi, G.K. Household Energy Poverty Index for India: An analysis of inter-state differences. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, H.S.K.; Hari, L. Towards a new approach in measuring energy poverty: Household level analysis of urban India. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.H.; Sadath, A.C. Energy poverty and economic development: Household-level evidence from India. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurat-ul-Ann, A.-R.; Mirza, F.M. Determinants of multidimensional energy poverty in Pakistan: A household level analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12366–12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Yoon, S. Reducing energy poverty: Characteristics of household electricity use in Vietnam. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 59, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.A.; Hasanujzaman, M. Multidimensional energy poverty in Bangladesh and its effect on health and education: A multilevel analysis based on household survey data. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Madaleno, M.; Inglesi-Lotz, R.; Taskin, D. Race and energy poverty: Evidence from African-American households. Energy Econ. 2022, 108, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, G.M.F.; Leder, S.M. Energy poverty: The paradox between low income and increasing household energy consumption in Brazil. Energy Build. 2022, 268, 112234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, A.P.; Lant, P.A.; Sridharan, S.; Smart, S.; Greig, C. The role of private sector off-grid actors in addressing India’s energy poverty: An analysis of selected exemplar firms delivering household energy. Energy Build. 2019, 191, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Yan, D.; Bouzarovski, S.; Zhang, Y. Energy poverty and thermal comfort in northern urban China: A household-scale typology of infrastructural inequalities. Energy Build. 2018, 177, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Malakar, Y.; Davies, P.J. Multi-scalar energy transitions in rural households: Distributed photovoltaics as a circuit breaker to the energy poverty cycle in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Rodríguez, L.; Sánchez Ramos, J.; Guerrero Delgado, M.; Molina Félix, J.L.; Álvarez Domínguez, S. Mitigating energy poverty: Potential contributions of combining PV and building thermal mass storage in low-income households. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assareh, E.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Ghersi, D.E.; Farhadi, E.; Keykhah, S.; Lee, M. Energy, exergy, exergoeconomic, exergoenvironmental, and transient analysis of a gas-fired power plant-driven proposed system with combined Rankine cycle: Thermoelectric for power production under different weather conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, C.R.; Panchal, H.N.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Ghasemi, M.H.; Alrubaie, A.J.; Sohani, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Solar Desalination Systems Powered by Solar Energy and CFD Modelled. Energies 2022, 15, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierszcz, K.; Grenda, B.; Szczurek, T.; Chen, B. The importance of geothermal energy in energy security: Towards counteracting energy poverty of households. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2019, Granada, Spain, 10–11 April 2019; Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision. 2020; pp. 771–781. [Google Scholar]

- Poblete-Cazenave, M.; Pachauri, S. A model of energy poverty and access: Estimating household electricity demand and appliance ownership. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G. The impact of household energy poverty on the mental health of parents of young children. J. Public Health 2022, 44, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Xu, D.; Li, S.; Baz, K. Health implications of household multidimensional energy poverty for women: A structural equation modeling technique. Energy Build. 2021, 234, 110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashagidigbi, W.M.; Babatunde, B.A.; Ogunniyi, A.I.; Olagunju, K.O.; Omotayo, A.O. Estimation and determinants of multidimensional energy poverty among households in Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olang, T.A.; Esteban, M.; Gasparatos, A. Lighting and cooking fuel choices of households in Kisumu City, Kenya: A multidimensional energy poverty perspective. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeku, K.O.; Meyer, E. Socioeconomic implications of energy poverty in South African poor rural households. Acad. Entrep. J. 2019, 25, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Shu, H.; Yi, H.; Wang, X. Household multidimensional energy poverty and its impacts on physical and mental health. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawumi Israel-Akinbo, S.; Snowball, J.; Fraser, G. An Investigation of Multidimensional Energy Poverty among South African Low-income Households. South Afr. J. Econ. 2018, 86, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgwambani, S.L.; Kasangana, K.K.; Makonese, T.; Masekameni, D.; Gulumian, M.; Mbonane, T.P. Assessment of household energy poverty levels in Louiville, Mpumalanga, South Africa. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy, DUE, Cape Town, South Africa, 3–5 April 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terfa, Z.G.; Ahmed, S.; Khan, J.; Niessen, L.W.; on behalf of the IMPALA Consortium. Household Microenvironment and Under-Fives Health Outcomes in Uganda: Focusing on Multidimensional Energy Poverty and Women Empowerment Indices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Han, P.; Sharma, V.K. Socio-economic determinants of energy poverty amongst Indian households: A case study of Mumbai. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweke, A.T.; Navrud, S. Valuing energy poverty costs: Household welfare loss from electricity blackouts in developing countries. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Koch, S.F. Measuring energy poverty in South Africa based on household required energy consumption. Energy Econ. 2021, 103, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murombo, T. Regulating energy in South Africa: Enabling sustainable energy by integrating energy and environmental regulation. J. Energy Natural Res. Law 2015, 33, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduka, E. How to get rural households out of energy poverty in Nigeria: A contingent valuation. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longe, O.M.; Ouahada, K. Mitigating household energy poverty through energy expenditure affordability algorithm in a smart grid. Energies 2018, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Streimikiene, D.; Lekavičius, V.; Baležentis, T.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Abrhám, J. Climate Change Mitigation Policies Targeting Households and Addressing Energy Poverty in European Union. Energies 2020, 13, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S.; Smyth, R. Ethnic diversity, energy poverty and the mediating role of trust: Evidence from household panel data for Australia. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boemi, S.-N.; Papadopoulos, A.M. Energy poverty and energy efficiency improvements: A longitudinal approach of the Hellenic households. Energy Build. 2019, 197, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, E.; Arsenopoulos, A. Investigating EU financial instruments to tackle energy poverty in households: A SWOT analysis. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2019, 14, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.V.; Rovinaru, M.D.; Pirvu, M.; Bako, E.D.; Rovinaru, F.I. Renewable Energy Generation and Consumption Across 2030—Analysis and Forecast of Required Growth in Generation Capacity. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2020, 19, 746–766. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, K.; Tsantopoulos, G.; Arabatzis, G.; Andreopoulou, Z.; Zafeiriou, E. A spatial decision support system framework for the evaluation of biomass energy production locations: Case study in Regional unit of Drama, Greece. Sustainability 2018, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arabatzis, G.; Malesios, C. Pro-Environmental attitudes of users and not users of fuelwood in a rural area of Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zografidou, E.; Petridis, K.; Petridis, N.; Arabatzis, G. A financial approach to renewable energy production in Greece using goal programming. Renew. Energy 2017, 108, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Istudor, N.; Dinu, V.; Nitescu, D.C. Influence Factors of Green Energy on EU Trade. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2021, 20, 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Peng, S.; Song, W.; Peng, J. Relationship between Enterprise Technological Diversification and Technology Innovation Performance: Moderating Role of Internal Resources and External Environment Dynamics. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2020, 19, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty-fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasheminasab, H.; Streimikiene, D.; Pishahang, M. A novel energy poverty evaluation: Study of the European Union countries. Energy 2023, 264, 126157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Su, T.D. The influences of government spending on energy poverty: Evidence from developing countries. Energy 2022, 238, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Butt, K.M.; Xu, D.; Ali, M.; Baz, K.; Kharl, S.H.; Ahmed, M. Measurements and determinants of extreme multidimensional energy poverty using machine learning. Energy 2022, 251, 123977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Research Objectives and Main Outcomes | Year/Territory |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | The exploration of vulnerability to heating-related energy poverty in Swedish single-family housing was developed by analyzing factors that influence households’ self-perceived ability to pay for heating as well as their self-perceived flexibility capital. The study provided a better understanding of energy vulnerability while showing that integration of energy vulnerability with flexibility capital can enhance researchers’ understanding of those challenges offered by a transitioning energy system in both Sweden and globally. | 2022/North Europe |

| [2] | The study reviewed indices for energy poverty assessment from households’ perspectives and identified 34 indexes for energy poverty assessment. The study provided valuable insights for selecting the best indicators for energy poverty assessment. | 2021/North Europe |

| [3] | The study found that energy poverty in developed and industrialized economies, such as Germany has been associated with household composition, educational attainment, labor force status, energy-inefficient housing, and the heating system in place. | 2021/North Europe |

| [4] | The study dealt with hidden energy poverty emerging from residents’ reactions to their impaired situation. The case study in Austria shows that self-restriction in energy use and properly defined energy poverty cases should be assessed in alignment with high energy expenditures in association with low-income and poor housing conditions. | 2022/Central Europe |

| [5] | The study analyzed the changes in energy poverty in Poland during 2010–2018 and revealed a slow but visible decrease in energy poverty in the country. The study found that investments in RES had a positive impact on energy poverty reduction. | 2021/Central Europe |

| [6] | The coping strategies of energy-poor households in urban settings in France, Spain, Austria, and North Macedonia were assessed. Based on the interviews among energy vulnerable households, the study showed that these strategies are manifold and complex, being related to household empowerment and the depletion of energy vulnerable households’ resilience reserves that are induced and guided by coping strategic and structural lock-ins. | 2021/Central Europe |

| [7] | The assessment of the effectiveness of the two measures in reducing winter energy poverty: Thermal social allowance (TSA) and thermal energy cheque (TEC) were performed in Spain, showing that the main imitations in the design of the TSA led to a reduction in winter energy poverty of only 1%, whereas the implementation of the TEC reduced it by 11%. These two measures were proven as ineffective medium-long-term policies since they are expensive and they do not consider other energy poverty characteristics, such as that of low energy efficiency of housing. | 2021/Mediterranean Europe |

| [8] | The study provided a survey of 384 households in Northern Greece, which had high dependence on energy needs, especially at the half-year mark. The study revealed that energy poverty affects a significant proportion of households surveyed, but only in Greece. | 2020/Mediterranean Europe |

| [9] | For a better understanding of the energy poverty in Portugal, a case study combining the use of an energy poverty vulnerability index, while deploying a detailed quantitative analysis in which 3092 civil parishes were interviewed at 100 households in ten hotspots, was based on proper mapping-based planning. Results revealed that besides the phenomenologically accepted situation that households are reasonable to be comfortable feeling both cold in the winter and hot in the summer at homes, either in the winter or in the summer, there is a subtle attitude hinting the social-recognized problem of energy poverty and, then, to activate citizens to confront its negative consequences to their well-being and good health. | 2019/Mediterranean Europe |

| References | Research Objectives and Main Outcomes | Year/Territory |

|---|---|---|

| [11] | Energy self-restriction at households in China was assessed, and the main findings showed that living in (a) large, old, and low-level insulated apartments that are also deprived of energy service equipment and (b) rental housing are linked with energy poverty. The distinct characteristics between energy poverty and non-energy poverty are linked to the area of residence and to the energy installations. Self-restriction restrains energy consumption and worsens the energy poverty situation in households. | 2022/Asia |

| [12] | The energy poverty index was developed for South Asia (2001–2018) by quantifying the size and scope of energy poverty while investigating the relevance of socio-economic positions in multi-dimensional energy poverty. The variables of analysis were the place/position of the houses, the number of occupants, as well as the age of the main caregiver for them. The study revealed that Bhutan’s energy poverty index was the highest one, followed by the Maldives and Bangladesh. Contrarily, India and Pakistan were proven to be the least energy-poor countries. This study also proposed policies to eradicate energy poverty and to support policymakers in developing and implementing regional strategies. | 2022/Asia |

| [13] | Energy poverty assessment was performed using China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data. The income levels and the energy decision-making were determined by the impact of cognitive capability on household energy poverty, showing the supportive role of cognitive capability against energy poverty eradication in China. | 2022/Asia |

| [14] | The multi-dimensional energy poverty index for six provinces was deployed in China. This research was organized into three states of local households’ energy poverty, scaled as: multi-dimensional, severe multi-dimensional, and non-multi-dimensional. It can be signified by the lowering of multi-dimensional energy poverty among these six provinces. Indeed, the majority of the households had migrated to better states, thus implying a non-energy poverty trap in China. However, there were vulnerability risks for some households returning to poverty. | 2022/Asia |

| [15] | The household survey in China revealed that tightening environmental regulations can cause greater energy affordability problems for households using non-clean energy. At the same time, convenient and affordable (at lower prices) clean energy allows households to have access to energy and, at the same time, to control the adverse effects of environmental regulations imposed by households’ energy poverty. | 2022/Asia |

| [16] | Based on China Family Panel Studies data, the study investigated the situation of national energy poverty. In particular, the effect mechanism on livelihood was conducted by considering income, expense, insurance, health, and future attitude, all of which counted for a comprehensive index of family life quality. The research findings provided support for policymakers to address energy poverty in China. | 2022/Asia |

| [17] | A northern China-scaled household survey showed that energy poverty was intensified by replacing coal with electricity and gas. Other factors of energy poverty were found to be lower income, less education, and smaller household sizes. It is necessary to denote that the design of energy transition policies for low-carbon transition should take into account its distributional effect. | 2022/Asia |

| [18] | The study deployed two types of energy poverty: (a) extensive and (b) intensive; the latter is considered the net effect and heterogeneity of energy poverty on rural labor wages. The study showed that both these types of energy poverty sustained a significant negative effect on the wages of rural workers. Moreover, intensive energy poverty sustained a higher marginal effect on the wages of rural workers compared to extensive energy poverty. The study showed that the enhancement of energy consumption in rural areas is vital to eliminating energy poverty; thus, policies should take labor force heterogeneity and regional heterogeneity into account. | 2021/Asia |

| [19] | The adjusted multi-dimensional energy poverty index (MEPI) was assessed for Asian countries. The study showed that variables such as house size, household wealth, education, and gender of the head of the household are the main socio-economic determinants of increased multi-dimensional energy poverty. Contrarily, a significant and positive mitigation of multi-dimensional energy poverty was reported for the variables of place of residence, ownership status of housing, family size, and age of the primary breadwinner. | 2020/Asia |

| [20] | The study conducted in the Kerala region revealed that electrified households faced intermittent power outages while they did not have access to power backup facilities. Although most households had access to clean cooking, they also utilized extensive biomass, such as firewood for fuel-wood stacking. The study showed that effective tackling of energy poverty is not only an issue of economic security but also an indicator of how energy policies can consider caring and influencing the habits and customs of citizens/energy consumers. | 2022/India |

| [21] | The set of 15 key energy indicators, representing multiple dimensions of energy poverty, was selected by deploying a principal component analysis (PCA) in India. The four types of households in India were characterized as ‘least energy poor’, ‘less energy poor’, ‘more energy poor’, and ‘most energy poor’. It found that 65% of Indian households were evaluated as ‘more and most energy poor’, showing the high energy poverty in the country. | 2020/India |

| [22] | The study conducted in India found that energy poverty was primarily associated with deprivation in cooking and that a greater incidence of energy poverty was manifesting in larger urban areas. In parallel, complementary measures envisaged energy poverty of energy-poor areas more accurately, thus, shaping appropriate pro-poor energy policies. | 2020/India |

| [23] | An empirical study applying the Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI) was conducted in India. It was determined that energy poverty could be considered quite extensive in India, showing substantial variations across national districts. The negative relationship between economic development, was reported and urban development, with energy poverty being the most vital component of economic development in education. Higher levels of education had a positive impact on reducing energy poverty in India. | 2019/India |

| [24] | Multi-dimensional energy poverty was assessed in Pakistan by deploying logistic regression estimates, proving that male-headed households showed a higher probability of being energy poor, while offering foreign remittances to households can increase their annual income and make them less energy poor. Moreover, improving housing conditions and focusing on housing located in urban areas can significantly decrease energy poverty in all quantiles. Overall, provincial and regional differences should allow governmental policymakers to alleviate multi-dimensional energy poverty through more realistic and feasible ways of accessing energy sources. | 2021/Pakistan |

| [25] | The study investigated the ways in which a national grid expansion in Vietnam can be translated into households’ electricity use over time, thus, playing an important role in increasing household income through electricity consumption. The study showed that an increase in electricity access could not turn directly into an increased use of electricity for low-income households, but it could stress out the gap between low and high income households. Other influencing factors were the education level of the household head, household size, and type/quality of housing. | 2020/Vietnam |

| [26] | The multi-dimensional energy poverty index (MEPI) was assessed in Bangladesh based on the latest household income and expenditure survey (HIES), showing that energy poverty decreased by 53.79%, 43.51%, and 36.33% in 2005, 2010, and 2016, respectively. It can be also denoted that the health and education status of households can be negatively linked to the multidimensional energy poverty. | 2021/Bangladesh |

| [27] | This study examined the effect of race on energy poverty by conducting surveys with representative U.S. households. It was reported that African-American households were more prone to energy poverty exposure, while health and income were determinant factors by which race could influence energy poverty. Therefore, it was argued that subsidy programs should provide energy at preferentially discounted rates and easy access to populations of specific demographics. | 2022/America |

| [28] | The behavioral factors of a vulnerable population associated with their energy consumption were the research focus of this study. The study showed that energy consumption had increased over the years due to the expansion of the built area, number of occupants, quantity of the equipment, time of the year (summer), and family composition. | 2022/America |

| Domains | Energy Poverty Framework—Domains of Analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| References | ||

| Historical and Situational Background of Energy Poverty | ||

| [62] | Energy poverty is related to issues of domestic energy deprivation in many European countries, including Greece, Spain, Slovakia, Poland, Germany, and Belgium. Contrarily, the “energy precariousness” entity has been enshrined in official policies and discourses in France. Energy poverty is also involved in the European “Third Energy Package” and varies among the bodies and organizations that adopted policy documents. It could be also denoted that in the US and Australia domestic energy deprivation has been characterized as an underestimated issue to attract policy attention to date. Energy poverty extensively impacts well-being and health, mainly referring to the inability to access fuels in the home, along with vulnerability to open fires and poor indoor air conditions, especially regarding fumes and smoke from open cooking fires that cause the death of 1.5 million people, mainly women and children, annually. Developed countries are also affected by energy poverty, especially regarding the issues of personal safety, household time budgets, labor productivity, and income. It can be also denoted that energy poverty could be considered a striking gendered problem, since women are more subjected to inadequate energy access, subtle discrimination, and restrict resources for decision-making. | |

| European Union (EU) Context | ||

| [62] | In the EU, energy poverty is primarily recognized as an issue emerging from institutional factors, political economies, infrastructural legacies, housing structures, and varied access to utility services. While national-scaled policy measures are feasible and realistic, there is also a need for implementing comprehensive agendas for energy poverty alleviation by transnational bodies, such as the EU. In this respect, geographical perspectives and diversification in developed countries regarding energy deprivation are linked to a greater awareness of its health impacts and amelioration policies. At this point, it is noteworthy to note that mental health issues and well-being are steadily recognized as important topics, followed by episodes of respiratory, circulatory morbidity as well as “excess winter” deaths. | |

| [63] |

| |

| International Context | ||

| [62] |

| |

| [64] | International government policies through public spending should alleviate energy poverty, but little attention has been devoted to investigating the effects of government spending on energy poverty, especially among developing countries. Therefore, it is crucial to research the influence of government spending on energy poverty. In this study, it was reported that government spending has a U-shaped effect on energy poverty, implying that increases in government spending may alleviate energy poverty until a certain level, whereas excessive spending can impede energy prosperity, and institutional quality could support government spending towards economic growth and the confrontation of income inequality. | |

| [65] | The deployment of supervised machine learning algorithms can identify the most pertinent and multi-faceted socio-economic aspects of energy poverty, showing that among them the most prevalent are that of: wealth of a household, home size, marital status of residents, as well as place of residence. It was also argued that those socio-economic determinants have policy significance to eradicate severe energy poverty, offering incentives and allocating resources, especially for those “energy-marginalized and poor” susceptible developing countries of Asia and Africa. | |

| Proposals—Guidelines—Challenging Issues of Energy Poverty | ||

| [62] |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Streimikiene, D.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Energy Transition. Energies 2023, 16, 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020610

Streimikiene D, Kyriakopoulos GL. Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Energy Transition. Energies. 2023; 16(2):610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020610

Chicago/Turabian StyleStreimikiene, Dalia, and Grigorios L. Kyriakopoulos. 2023. "Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Energy Transition" Energies 16, no. 2: 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020610

APA StyleStreimikiene, D., & Kyriakopoulos, G. L. (2023). Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Energy Transition. Energies, 16(2), 610. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020610