Abstract

The main objective of this research is to identify the scope of the use of EU funds for the formation of a low-carbon economy by enterprises providing energy services in Poland in 2014–2020. As a result of the identification, a model for the use of EU funds based on the following criteria was identified: the purpose of the investment, the type of fund, the type of support program, the range of support values and the form and level of funding. As a research gap has been identified due to the insufficient investigation of the use of EU funds by the largest energy companies in Poland to shape a low-carbon economy, the findings presented are novel and contribute to a better understanding of the use of EU funds by Poland’s largest energy sector companies. Data on investment projects financed by EU funds were obtained from the database of the Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy for 2014–2020, while the characteristics of the companies were obtained from industry reports, the National Court Register and the Central Statistical Office. The results showed that EU funds were important in the financing of investments by the largest energy companies to decarbonize the economy. The analysis showed that the surveyed companies were pursuing the goals of Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council for energy efficiency, primarily concerning a low-carbon economy. Most EU aid funds were used for infrastructure investments, including those related to renewable energy sources. Little use has been made of EU funds for innovation and public awareness.

1. Introduction

One of today’s global challenges, achievable through tasks at the level of national economies, is to shape a low-carbon economy and increase the use of renewable energy sources. This is due to the need to halt or at least reduce the negative effects of climate change. Increasing combustion of fossil fuels, resulting from the increase in the level of economic development but not based on the principles of sustainable development, is considered as the main cause of climate change [1,2].

A low-carbon economy is most often associated with having a significant share of renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, the development and use of low-carbon technologies, the promotion of new consumption patterns and the reduction of emissions of harmful dust and gases [3,4]. It is widely recognized that its growth is achievable by integrating all activities around low-carbon technologies and practices, efficient energy solutions, clean renewable energy and green technological innovations [5,6]. Improving existing technologies to enhance their climate-friendliness or developing new technologies is accepted as an important part of shaping a low-carbon economy [7]. The European Strategic Energy Technology Plan (SET-Plan) identified ten research and innovation activities (renewable energy technologies, technology cost reduction, new consumer technologies and services, resilience and security of energy systems, new materials and technologies in buildings, energy efficiency in industry, competitiveness in the global battery and electromobility sector, renewable fuels and bioenergy, carbon capture and storage, and nuclear security) that are also expected to lead to improved decarbonization of the economy [8].

With each successive financial perspective, the European Union is increasingly focused on implementing measures to develop and support a low-carbon economy, as part of the implementation of its sustainable development policy. The European Union’s strategic documents assume that climate neutrality will be achieved by 2050 [9]. In 2015, key policy goals were defined, indicating the need to diversify Europe’s energy sources and to ensure energy security through solidarity and cooperation among EU countries. In addition, these defined policy goals pointed to the need to ensure the functioning of a fully integrated internal energy market, allowing the free flow of energy in the EU through adequate infrastructure and without technical or regulatory barriers. The stated goals also stressed the importance of improving energy efficiency and reducing dependence on energy imports. Moreover, they emphasized the need to reduce emissions and stimulate job creation and economic growth.

Another policy goal relevant to further sustainable development is the decarbonization of the economy and the transition to a low-carbon economy in line with the Paris Agreement of 2015. Promoting research in low-carbon and clean energy technologies, and prioritizing research and innovation to stimulate the energy transition and improve competitiveness is, therefore, an important goal [9].

In addition, the EU stressed that it is important to create strong, innovative and competitive European companies that develop the products and technologies needed to achieve energy efficiency and low-carbon technologies in Europe and beyond [10]. These enterprises include energy companies, which, as energy distributors, are crucial to the implementation of energy policy. The issues of this study, while they seem recognized, are not clarified in terms of large government-owned enterprises (public sector). However, there is an extensive literature on the multifaceted analysis of the use of EU funds to create an EU low-carbon economy by states and regions [11,12], small- and medium-sized enterprises [13,14] and households [15].

In the case of large enterprises in Poland, research is less frequent. Typically, energy companies are huge, state-owned corporations that receive more financial and regulatory support than do smaller business units. Moreover, it is more common to analyze the financial situation of these enterprises [16] rather than the direction of their investments from EU funds. Therefore, it is important to recognize how EU funds are spent on tasks related to the use of renewable energy sources (RESs) and decarbonization of the economy. This will also be of applied importance since the contemporary challenges of economic development clearly indicate a transition to a low-carbon economy.

From the perspective of the functioning of a state’s economy, a low-carbon economy simultaneously creates opportunities for the emergence of innovative industries and services that will ensure competitiveness in the long term. Its development must be coordinated with other measures to improve the energy efficiency of the economy. Without such measures, a phenomenon described in the literature as “Jevons’ paradox” may occur. This is based on the fact that a technical change associated with increasing the efficiency of the use of a resource usually leads to a build-up in its consumption [17,18].

One of the key EU state economies, including energy economies, is Poland, whose transformational problems in the energy sector are still evident. Since 2004 (Poland’s accession to the EU), the Polish economy has made significant progress in restructuring, modernization, the creation of market institutions and internationalization. At the same time, some sectors remain underinvested or unchanged. In the case of the energy sector, there are still numerous problems, and many of the investment projects being implemented are at varying degrees of progress. Poland’s situation is an example of such an economy where after crossing a certain level of economic development, there is a so-called “turning point” and environmental expenditures begin to increase. This relationship in relation to wealth and income inequality was recognized by Kuznets [19].

Unfortunately, the Polish power industry is still based on hard coal resources. Meanwhile, EU climate policy is making coal power generation more expensive, coal mining costs are rising, and power sector companies are financially committed to restructuring the coal industry (The current political situation related to the war waged by Russia on Ukrainian territory is forcing Poland to increase its use of coal resources for energy production. However, the long-term policy indicates the need to minimize the scale of use of this energy carrier). This causes difficulties in the operation of enterprises in the energy sector in Poland. Nevertheless, the availability of financial support from the European Union is becoming both a stimulus and an important mechanism for financing investment projects in the energy sector. Enterprises in this sector benefit from the full range of financial support, but investment projects aimed at the generation and distribution of energy from renewable energy resources (RESs), as well as any innovative projects that modernize the energy sector in any dimension, should be considered crucial in the context of a low-carbon economy.

The main objective of this research is to identify the scope of use of EU funds for the formation of a low-carbon economy by selected companies in the energy sector in Poland in 2014–2020. As a result of the identification, a model for the use of EU funds will be determined based on the following criteria: the purpose of the investment, the type of fund, the type of support program, the range of support values and the form and level of funding. The empirical research was aimed at verifying the research hypothesis, which assumed that the largest Polish energy companies have the greatest investment activity in projects aimed at shaping a low-carbon economy co-financed by EU funds, and the most important direction of the use of funds is the modernization or construction of energy infrastructure.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Low-Carbon Economy

The term “low-carbon economy”, although a concept widely met in scientific research, as well as development policy, is ambiguously understood [3,20]. Despite the fact that the low-carbon economy has not been clearly defined, it is based on two key elements: reducing greenhouse gas emissions (especially carbon dioxide) and increasing energy efficiency [6]. However, according to P. Gradziuk and B. Gradziuk [21], it is a more complex issue, encompassing a totality of activities that contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions while respecting the principles of sustainable development and being oriented towards innovation and competitiveness in the global market. It is also emphasized that the low-carbon economy should be understood in integrated terms, consisting of the development of low-carbon energy sources, improvement of energy efficiency and management of raw materials and materials, development and use of low-carbon technologies, prevention and improvement of waste management efficiency, and promotion of new consumption patterns [3,22,23]. An interesting point of view on the treatment of the low-carbon economy as a complex issue is presented by Xin et al. [24], who consider low-carbon development to consist of six concepts: low-carbon economy, low-carbon society, low-carbon city, low-carbon community and low-carbon life. Although there are opinions questioning the sense of its implementation in development processes [19], it should be recognized that it is one of the greatest challenges in economic development, at every territorial level—from local to global [25,26,27].

Currently, the EU’s approach to climate and energy policy is to achieve by 2030 such goals as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% (relative to 1990 levels), increasing the share of renewable energy in total energy consumption to at least 32% and enhancing energy efficiency by at least 32.5% [28]. Comparing the above targets to those of the Climate Package 2020 [29], a significant tightening of the European Union’s requirements for member states and climate targets is evident. In addition, the Investment Plan for Europe identifies opportunities and principles for financing strategic investments in key areas, including renewable energy and energy efficiency (among others), which are directly related to the low-carbon economy [8]. Moreover, the UN Sustainable Development Goals also emphasize the importance of transitioning to a low-carbon economy that will contribute to achieving the set goals [30].

From the perspective of the functioning of a state’s economy, a low-carbon economy simultaneously creates opportunities for the emergence of innovative industries and services that will ensure competitiveness in the long term. The low-carbon economy, according to the programmatic assumptions of the economic development of states and regions, should be of great importance, as it simultaneously generates profit for investors and economic growth for the country and causes a significant reduction in CO2 emissions [31,32,33]. With regard to businesses, improving old technologies (to enhance their climate-friendliness) and developing new technologies are considered important counters to climate change [7].

In recent years, a lot of research attention has also been paid to the formation of a low-carbon economy in Poland, most often pointing out its necessity but also the difficulties of implementation, due to the fact that the energy system relies heavily on coal and is highly concentrated [34,35,36].

2.2. EU Policies and Support Measures for a Low-Carbon Economy

The European Union defined a framework for targeting energy and climate policies for all member states and regions for the 2014–2020 period [37,38]. The framework integrates various goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions [39], securing fuel and energy supplies [40], and promoting growth, competitiveness and job creation. Paska and Surma analyzed these in the context of the so-called “Winter Package” [41] and drew attention to the impact of various EU documents on energy policy up to 2030 and the activities of energy companies. Responding to the need to develop the infrastructure necessary for the creation of a community energy market, an Infrastructure Package was presented back in 2010, the regulations of which were expected to force investment in the transmission infrastructure for electricity, gas, oil and carbon dioxide transport.

The challenge of implementing the abovementioned measures is the need to create optimal political and economic conditions, especially support and cooperation mechanisms between the private sector and financial institutions, as the realization of these projects will require significant financial resources [42]. Thus, at the same time as setting policy implementation goals for the energy sector, the EU has identified instruments for its support, including financial instruments. EU support measures are one of the major available instruments for financing investments in the energy sector. In countries and regions of Europe, in addition to this instrument, the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) are also used to a large extent. Nevertheless, it is within the framework of the Structural Funds that the greatest financial support of the energy sector has been noticed, which is due to the increased importance of this sector in the structural policy of the EU.

Member country financing of the energy sector depends on energy policy and EU state aid rules [43]. With regard to aid to the energy sector, these are the provisions of European Commission Regulation 651/2014 declaring certain types of aid compatible with the internal market in application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty [44] and the guidelines on state aid for environmental protection and energy-related objectives 2014–2020 [45]. Guided by these principles, EU countries may grant investment aid for the support for energy efficiency, investment in high-efficiency cogeneration systems solely for newly installed or renewed capacities, promotion of energy from renewable sources, energy-efficient heating and cooling systems, and for the construction or modernization of energy infrastructure [43]. All member states are applying for EU funds for these purposes, and as studies show, these goals are gradually being successfully achieved [42].

As Korbutowicz points out, the European Commission, with regard to programs and projects to support energy management tasks, is open to providing financial assistance. For example, it has not raised any objections to projects submitted by France, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland. Indeed, it usually does not raise objections and approves the provision of aid in the hope of developing the technology to reduce the high cost of renewable energy production. Positive assessment of support programs for renewable energy is most often justified by increasing the share of this energy in energy supply, reducing CO2 emissions, creating cross-border connections in energy supply and reducing the dependence of member states on the supply of other fuels, including reducing the use of coal [43].

In the years 2007–2013, Poland and Italy allocated the most funds from EU Funds to energy investments [46]. Between 2014 and 2020, more than EUR 11.5 billion was planned for energy efficiency investments across the EU, and this was more than twice as much as in 2007–2013 [47]. Support for energy efficiency and other sustainable energy investments grew unprecedentedly [48]. In the 2014–2020 period, the level of available funds was increased by more than 100%, the leverage of involving private funds was increased, the use of repayable instruments was increased, and energy services and Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) were promoted.

A profound evolution in the financing of energy-saving investments was also to take place in Poland. Beyond trends in the European-level organization of financial engineering for energy efficiency, Poland increased by more than 25% the amount of funds at the regional level, in addition to the number and variety of priority programs of the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management that were to support the involvement of Polish beneficiaries in programs financed at the European level. Above all, Poland sought to achieve the objectives of the Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council for energy efficiency [49]. The key tool for financial support of investments with EU funds for enterprises in the energy sector was the Operational Program Infrastructure and Environment, implemented in both 2007–2013 [50] and 2014–2020 [51]. The aim of this program was, among others, to protect air quality and improve the energy efficiency of enterprises. Within its scope, investments were undertaken in the thermal modernization of enterprise buildings, the modernization of heat sources and heating and electricity networks, and the construction of high-efficiency cogeneration units. The key source of financing for these tasks was the European Regional Development Fund, with additional funding from the Cohesion Fund and national and private funds required as own contribution.

2.3. Situation of the Energy Sector—The Case of Poland

Currently, the Polish electric power industry consists of several large capital groups and a few individual privatized power plants and energy distributors. Four large operators capable of competing with other European companies on the free energy market are assumed to operate: PEG Polska Grupa Energetyczna S.A., TAURON Polska Energia S.A., ENEA S.A. and ENERGA S.A. [52]. Despite the deep restructuring of the economy, the power sector is still dominated by significantly decapitalized assets. This applies to both electricity generation and transmission. The oldest units are being systematically shut down in the next few years, and by 2030, units with a total capacity of more than 16,000 MW will be out of service [53,54].

As Lipski [55], Jaworski and Czerwonka [56] note, as a member of the EU, Poland is subject to its policies, including the reduction of fossil energy sources, mainly coal. Meanwhile, the government’s policy was based on the use of coal as the main source of energy, and the vast majority of energy companies are state-owned, so they pursue the government’s interests. In addition, these companies have limited intangible assets, owning tangible assets instead. The state, as a major investor, is therefore not willing to pursue risky investment projects at the expense of the financial sector [57]. It has also been demonstrated that there is a negative impact of the amount of energy consumption and the share of renewable sources on the debt of energy companies [56]. Currently, energy market participants are operating under the pressure of high risks and conditions of current trends, taking place on a global scale, including, in particular, the progressive loss of the value of generation assets, the decline in the profitability of electricity generation in the current model, the negative impact of the energy industry on the environment, the growing awareness of consumers both as customers and energy market participants, changes in the structure of energy production, the changing costs of both technology and fuels, and the gradual depletion of fossil fuel resources [42]. This may be supported by funding from EU structural and investment funds. However, without taking other measures for the technological development of enterprises and the socio-economic development of the country, the use of renewable energy sources may be an unsustainable strategy with adverse effects.

Despite the difficulties indicated, it is necessary to build new generating capacity in the power industry and apply innovative solutions for the use of RESs. This is becoming necessary because of the European Parliament’s directive (No. 2005/32/EC), which forces a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and an increase in the use of energy from renewable sources by 2020. That is why large energy companies, most of which are integrated groups, are investing in this sector [55]. Thus, given the requirements of climate policy, the Polish energy sector is striving to make its fuel mix more balanced. TAURON, for example, is already a serious player in the RES market. The TAURON Group, through its investment activities, has sought to implement the latest technological solutions; the driving notion being that doing so should lead to the generation of cheap and clean electricity and heat while providing a tangible benefit to the natural environment [58].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Overall, we used databases published by government institutions in Poland as the basis for identifying enterprises and investment projects for shaping a low-carbon economy. The Local Data Bank [59] and The National Court Register [60] database published by the Central Statistical Office were employed to identify enterprises providing energy services. In addition, reports and documents on the functioning of the sector in Poland were used to determine the importance in the Polish energy market of individual enterprises [61,62,63]. Information on investment projects implemented with the support of EU funds was obtained from the official government database. The entity responsible for its publication is the Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy [64].

3.2. Research Procedure

The research involved three stages. The first was based on an analysis of literature and policy documents. It consisted of discerning the basis for shaping a low-carbon economy in Poland in light of EU policy. The second stage concerned the selection of companies and projects constituting the information base for further analysis. The source databases were the basis for selecting those enterprises that operate on the Polish market and, according to the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD 2007), belong to the group: generation and supply of electricity, gas, steam, hot water and air for air conditioning systems. Due to the subject of the study, representatives of that part of the aforementioned entities that are engaged in at least one of the listed activities that involved generation, transmission, distribution or energy trade were included. The final criterion for qualifying enterprises for the survey was their implementation of investment projects co-financed by EU funds. The compilation of information from all bases included 12,035 energy sector enterprises (2020) and more than 100,000 investment projects. The comparison of databases was the basis for selecting 8 energy service companies, which in total carried out 193 investment projects co-financed with EU funds between 2014 and 2020.

All projects undertaken by the selected companies were accepted for the study, and those that implemented Objective 04, which is to support the transition to a low-carbon economy, were analyzed in detail. Next, projects related to RESs were identified, and innovative projects (including those related to RESs) were identified separately. The final stage consisted of analyzing investment projects, which were considered from the following aspects: (1) the purpose of the project and its relation to EU policy goals, priorities and actions; (2) the type of fund; (3) the type of support program; (4) the value of the project; and (5) the level of EU funding. All the analysis criteria were related to individual enterprises in an attempt to determine whether the type of enterprise also has an impact on the way EU financial instruments are used in creating a low-carbon economy in Poland.

The dominant method was analytical research, including comparative research, which primarily served to detect structure and dependencies in the subject of the study. The course of action was inductive, involving the derivation of conclusions from premises that are their individual cases. On the basis of information about the investment projects studied, final generalizations were derived. Using quantitative data, inferences were made from detailed statistical summaries.

3.3. Characteristics of Selected Energy Sector Operators

Enterprises in the energy sector in Poland are recorded in the economic and statistical system in Poland in accordance with the Polish Classification of Activities (PCA 2007) and belong to the group: generation and supply of electricity, gas, steam, hot water and air for air conditioning systems. As per the aforementioned criteria for the selection of enterprises, 8 enterprises qualified for the study (Table 1). These are the most important enterprises in Poland from the point of view of their range of influence and scope of providing energy services. Their share in the volume of electricity injected into the grid in Poland in 2018 was more than 70% of the total energy market [65]. Each of the companies is an equity group, of which those with State Treasury (S.T.) participation dominate. Those with more than 50% share include the Polish Energy Group (PEG) (57.39% share of S.T.), Tauron Polish Energy (54.49% share) and Enea (51.5% share) [65]. Most are joint stock companies. From the point of view of the research problem, it is important that these are companies suitable for large investment projects, including companies planning to go public. ML System is among the companies that are also listed on the stock market. However, due to the slightly different nature of its business, it was not qualified for the study. ML System is a technology company engaged in research in the field of energy extraction with modern technologies. It produces solutions that find applications in both classic rooftop and ground-mounted photovoltaic installations, sustainable construction, land and water transportation, and the automotive industry. ML System does not produce or distribute energy but only provides the market with new solutions for obtaining energy from renewable sources.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enterprises by area of activity.

Moreover, in the energy industry, in addition to entities whose main activities are based on the production and supply of electricity, there are those providing consulting services, electricity audits, energy efficiency analyses (EnMS Polska Limited Liability Company), studies of the energy efficiency of technological processes (DB Energy), and services for the analysis of the profitability of the modernization of drive units and their implementation (DBE drives), as well as having an offer for the effective implementation of the co-generation of electricity and heat in industry (DBE cogeneration). An analysis of the data on the surveyed energy industry players shows that all are active in different fields, but energy generation and supply is typical. Of note, DB Energy’s business is focused on providing energy efficiency services to the industry.

4. Analysis

The subject of the analysis was the projects realized by the selected eight enterprises of the energy sector operating in Poland. Verification of the source material indicates that the business entities selected for the analysis carried out a total of 193 projects covered by financial support from EU funds in 2014–2020.

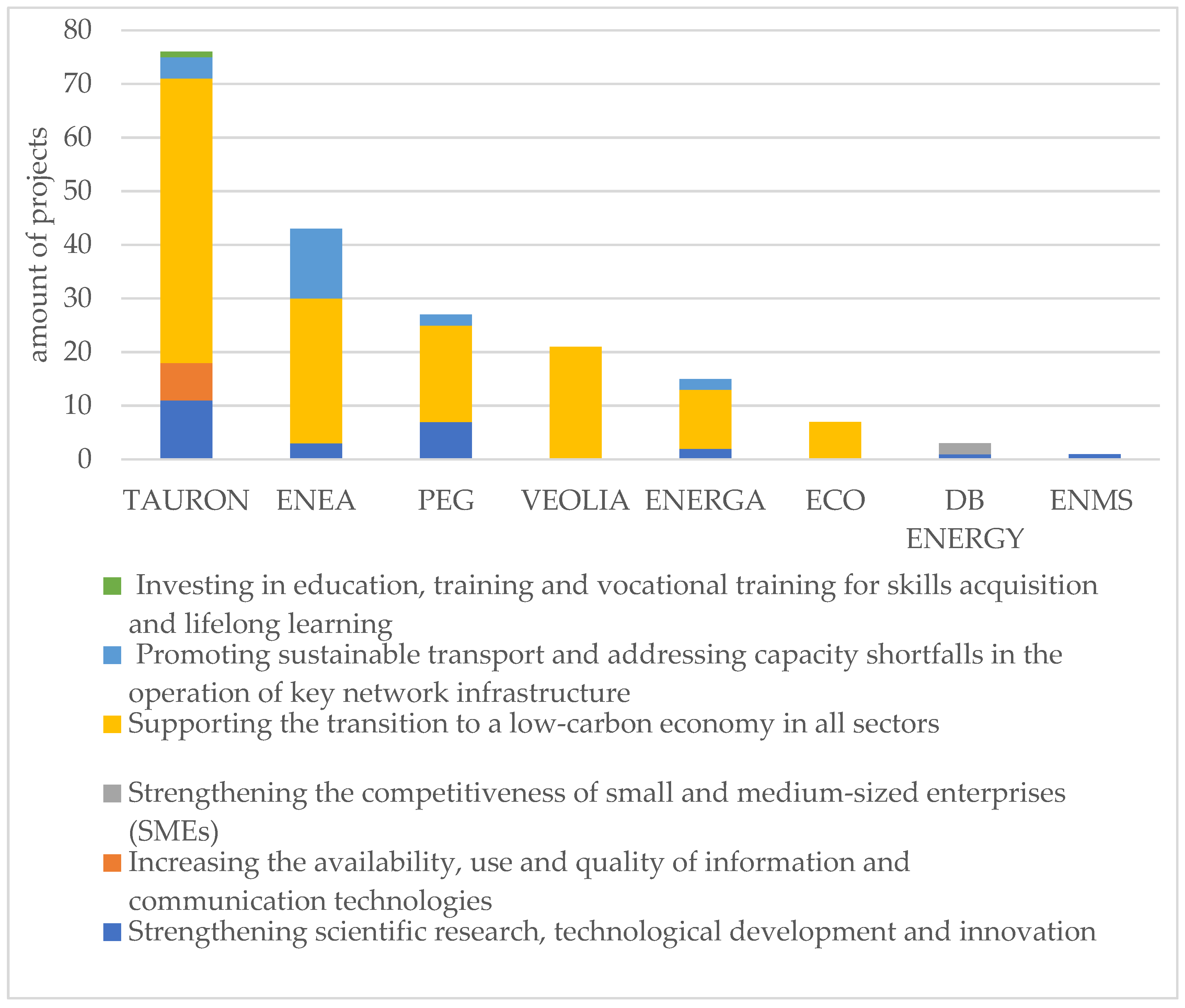

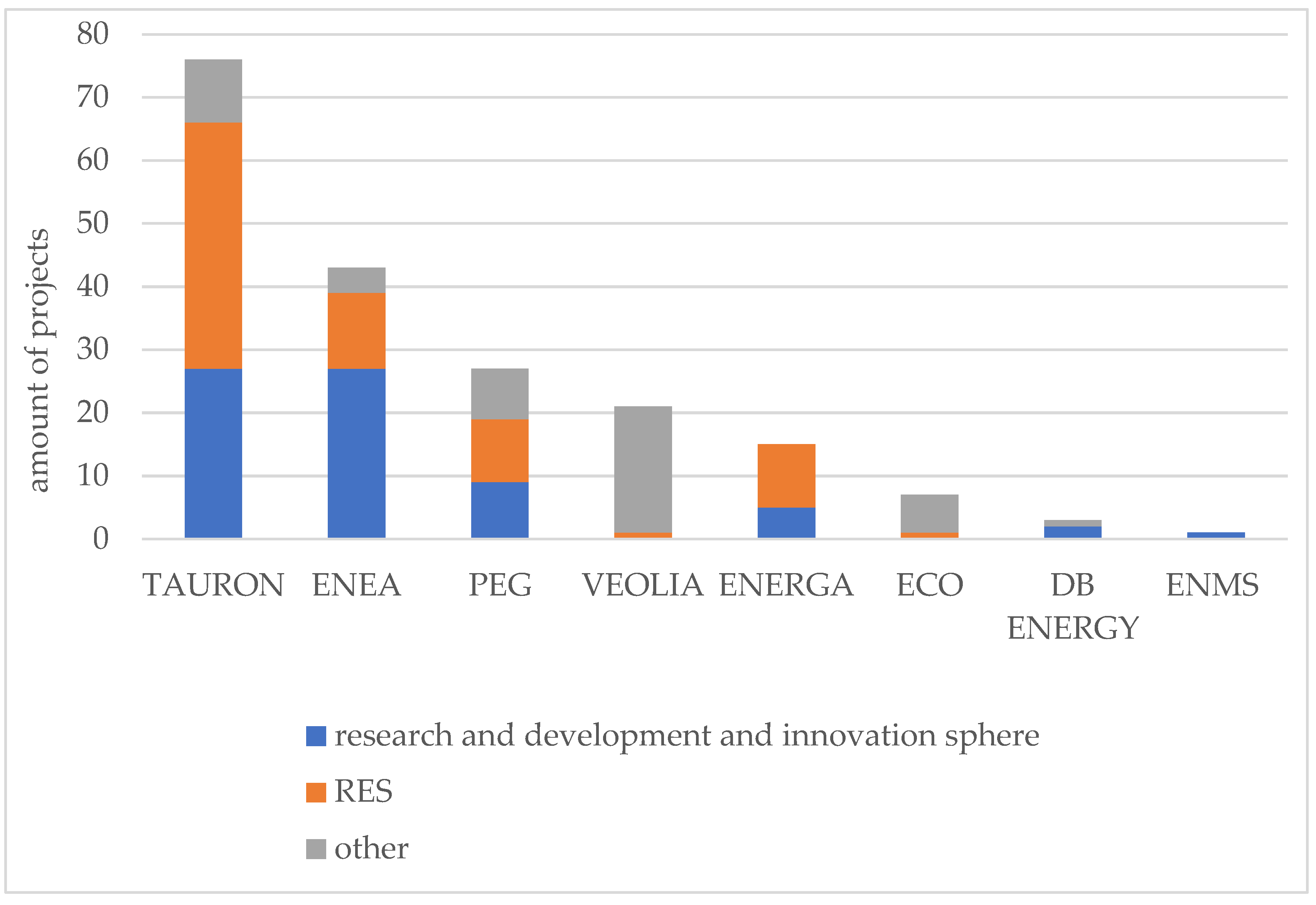

Of the subject companies, TAURON (76 projects) and ENEA Operator Ltd. (43 projects) implemented the largest number of EU-subsidized projects. Overall, they were responsible for 61.6% of the total number of projects put in place and should be considered, in this respect, as dominant on the Polish energy market. The remaining companies were of lesser importance, with PEG standing out among them, having enacted 27 projects, while VEOLIA carried out 21 and Energa executed 15 projects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of projects implemented by the analyzed enterprises.

In our analysis of the fields of activity of the invested energy sector, the emerging dominant activity was found to be energy storage and distribution. Accordingly, 80% of TAURON’s and ENERGA’s projects, 97% of ENEA’s, 92% of PEG’s and 100% of VEOLIA’s were aimed at supporting or developing this field. These activities involved both electricity and heat supplied to businesses and households and were derived from various sources. Those that provide services related to the operation of activities in the energy sector were also among the companies assessed. They support enterprises, local governments and building managers in their efforts to enhance their energy use efficiency. They perform energy audits of enterprises and provide services for implementing and maintaining energy management systems according to ISO 50001 (EnMs) (https://www.enms.pl/o-nas/, accessed on 10 November 2022).

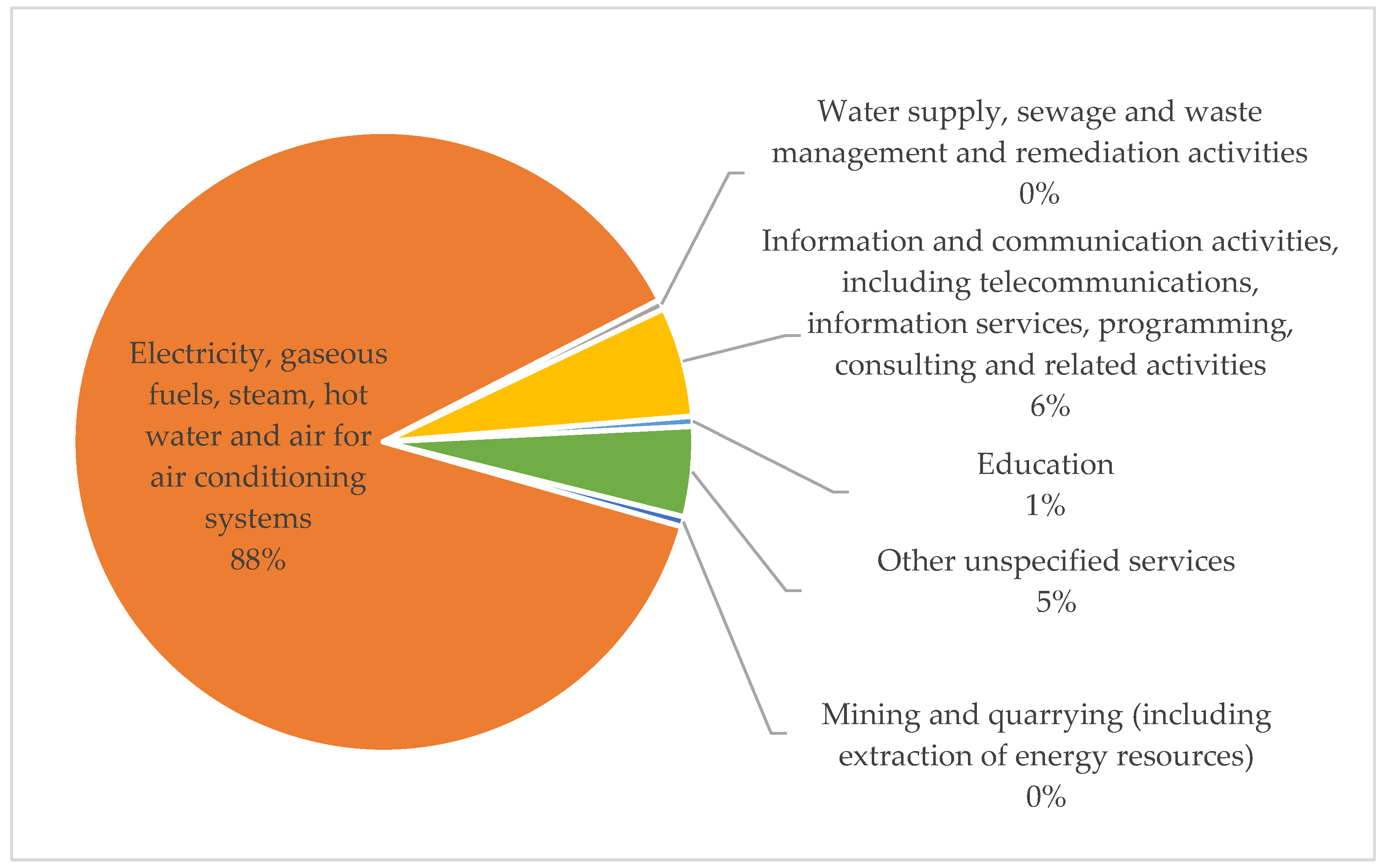

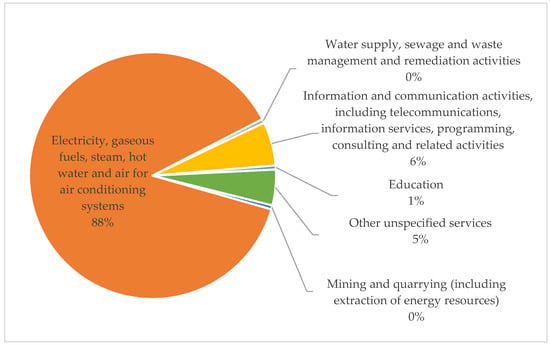

The classification of companies according to their fields of activity indicates that the investigated energy companies carried out pursuits beyond their indicated field (of which 87% of all projects were enacted), venturing into information and communication (including telecommunications, information services, programming and consulting). In addition, the category of other unspecified services transacted by energy companies, the percentage of projects, of which there was a minimum of 4%, included the following:

- −

- investments in infrastructure, capacity and equipment in SMEs directly related to research and innovation activities;

- −

- research and innovation processes in SMEs (including voucher systems, process innovation, design innovation, service innovation and social innovation);

- −

- development of SME activities, support for entrepreneurship and enterprise creation (including support for spin-off and spin-out enterprises).

Other areas of activity were carried out by a much smaller number of projects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Share of ongoing projects within the fields of activity. Source: own elaboration based on data from www.funduszeeuropejskie.pl (accessed on 10 March 2022).

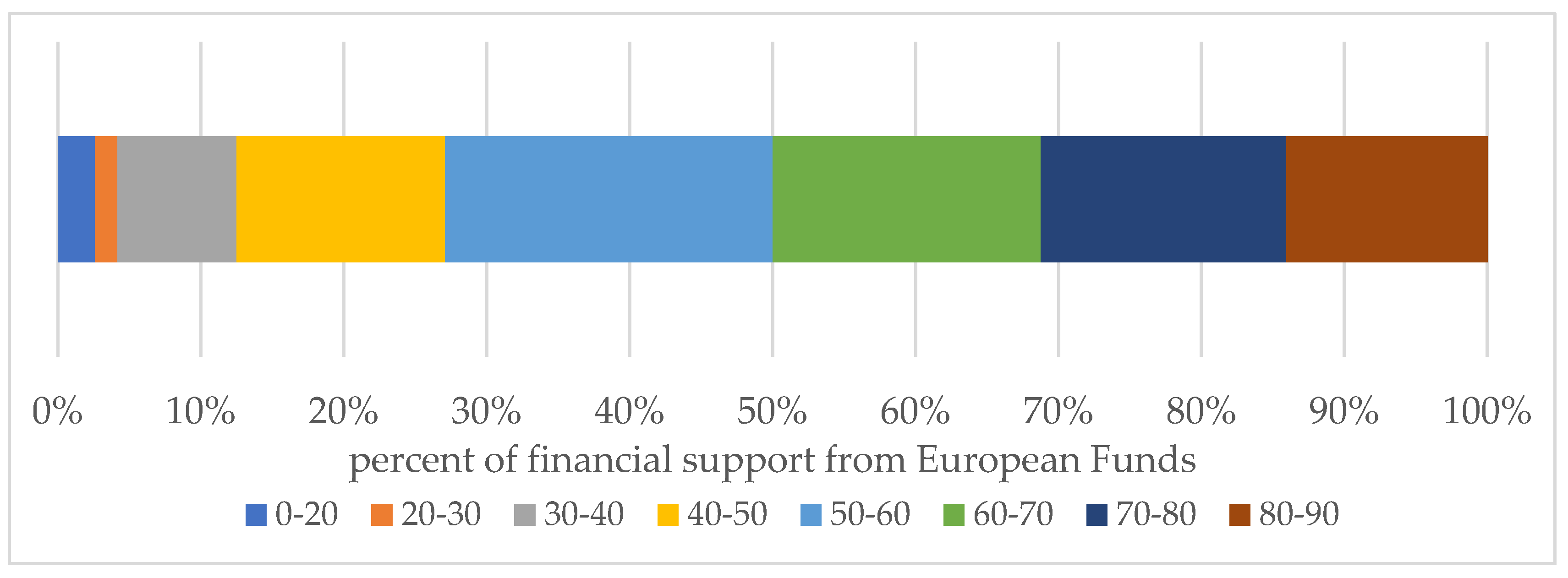

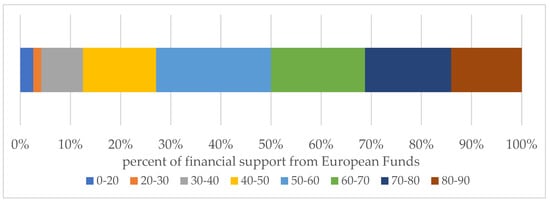

The level of EU funding for projects varied depending on several variables. Taking into account the principle of additionality of financing and the need for own funds, it can be said that most projects had financial support higher than the value of their own contribution. Support less than half of the project amount was received by 29% of the total number of projects (Figure 2). Most projects received support between 50–60% (45 projects) and 60–70% (36 projects), which together accounted for more than 40% of the total projects. TAURON (31 projects) and ENEA (22 projects) had the largest number of projects in these funding ranges. ENERGA had the most projects subsidized within 70–80% (7 projects).

Figure 2.

Share of numbers of projects implemented, specifying the level of co-financing from European Funds (distinguished intervals of EU financial support: 0–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, 60–70, 70–80 [%]). Source: own compilation based on data from www.funduszeeuropejskie.pl (accessed on 10 March 2022).

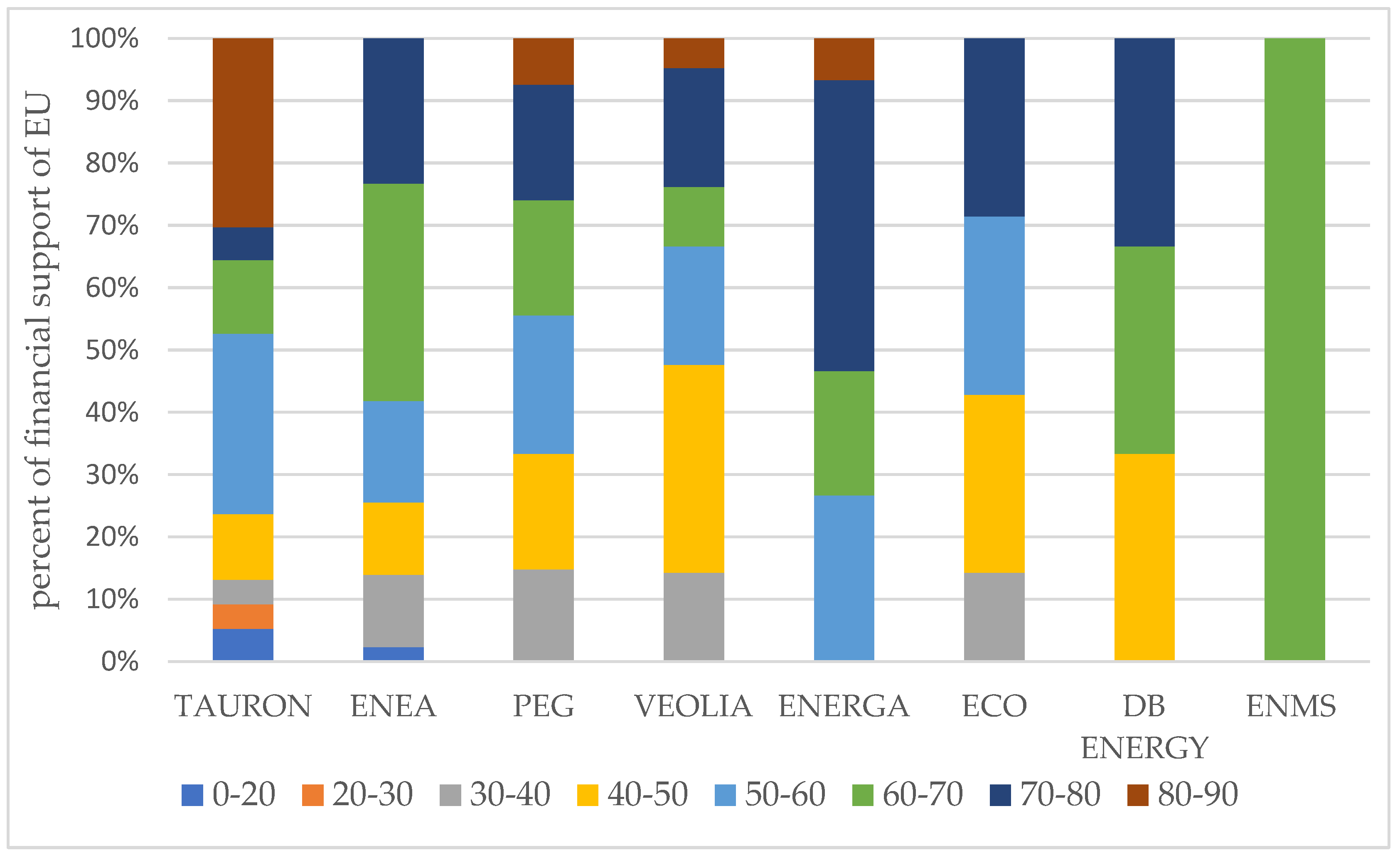

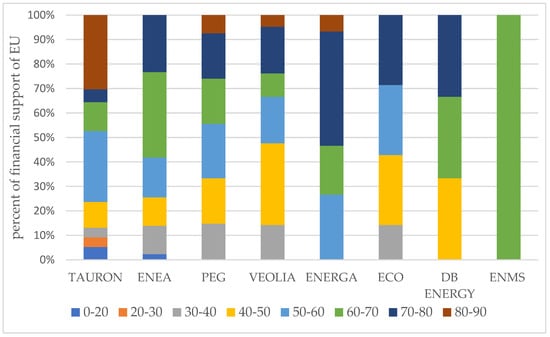

The highest level of support was gained by projects implemented by the largest companies and by projects incorporating a diverse range of fields (Figure 3). For example, a subsidy level exceeding 80% was received by TAURON for as many as 30% of all its projects. Projects implemented by the ENEA group, PEG and ENERGA also had high project support.

Figure 3.

Number of projects implemented by individual energy companies, specifying the level of financing from European funds (% of funding) (distinguished intervals of EU financial support: 0–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, 60–70, 70–80 [%]). Source: own compilation based on data from www.funduszeeuropejskie.pl (accessed on 10 March 2022).

The main sources of project funding were the European Regional Development Fund (54%), the Cohesion Fund (45%) and the European Social Fund (ESF) (0.5%). The structure of sources of support for projects is consistent with their nature. Both the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) are aimed at technological and infrastructural development, and the European Social Fund is aimed at supporting social development and so-called soft skills. The largest number of projects were carried out under the Infrastructure and Environment Operational Program 2014–2020, which is primarily intended for tasks in the field of environmental protection and infrastructural investment. This is a national program, which means that tasks financed through it have at least a supra-regional impact. In addition, an important instrument of support was the Regional Operational Programs, the scope of influence of which covers individual provinces in Poland. Thus, financial support from these projects covered tasks of regional scope. One project was financed by the Operational Program Knowledge Education Development, the funding source therein being the European Social Fund (Table 3). This distribution of funding sources indicates the implementation of mainly hard infrastructure projects (construction, modernization of the transmission network, reconstruction and construction of the power grid, etc.).

Table 3.

Sources of project funding.

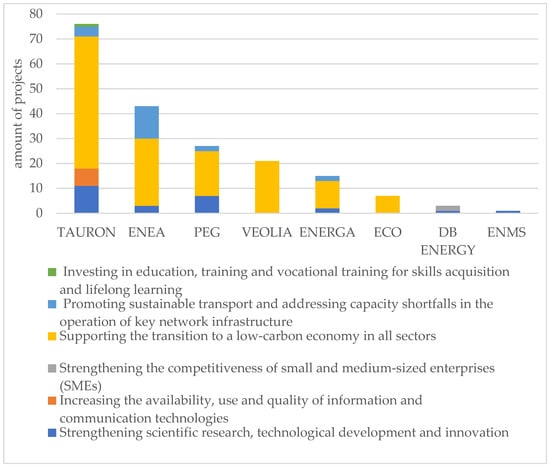

Investments undertaken by energy companies implemented six thematic objectives of the cohesion policy (Figure 4). The largest percentage of projects concerned the change-over to a low-carbon economy (71% of all projects). All projects implemented by Veolia and ECO were part of this objective; in the case of ENEA, it was 62% of all projects implemented by the company, while with PEG, it was 66% of projects. Tauron’s investments were 70% in line with the transition to a low-carbon economy, while ENERGA’s were 73%. The lowest percentage were projects aimed at strengthening the competitiveness of companies, under which DB Energy initiated two projects.

Figure 4.

Share of energy company implemented projects by cohesion policy objective. Source: own compilation based on data from www.funduszeeuropejskie.pl (accessed on 10 March 2022).

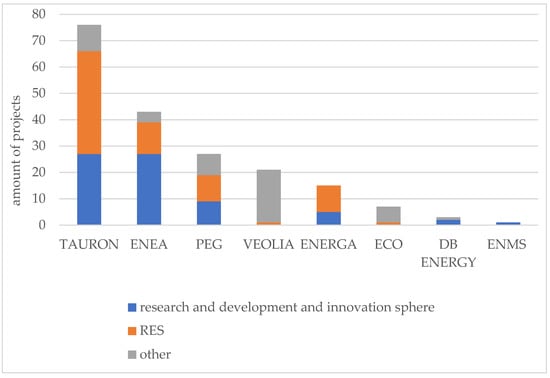

In the realization of a low-carbon economy, it is crucial to implement innovative projects incorporating new solutions and the use of renewable energy sources. Those aimed at strengthening research, technology development and innovation accounted for 37% of the total projects (Figure 5), and 38% were renewable energy projects. Analysis of the projects carried out by the surveyed companies indicated that four of them carried out investments that included renewable energy issues (Tauron, Enea, PEG and Energa). The same companies also carried out projects of an innovative nature. All of the innovative projects were financed by the ERDF, while projects implementing renewable energy sources were entirely financed by the Cohesion Fund.

Figure 5.

Share of innovative and renewable energy projects. Source: own compilation based on data from www.funduszeeuropejskie.pl (accessed on 10 March 2022).

This means that energy companies that dominate the energy market in Poland are willing to make investments aimed at developing technology and innovation. In the case of the implementation of renewable energy solutions, companies with a significant position in the energy market and those supplying energy on a large scale are also executing projects in this area. The percentage of projects related to the implementation of RES solutions is 38% of all projects enacted by companies and subsidized by the EU. Other projects not included in those of an innovative research and development or RES-related nature accounted for 25% of all projects. The analyzed projects were 98% financed as non-refundable grants and only 2% as a refundable grant. These included two projects for the modernization of water pumps at ENEA and PEG.

The level of co-financing of investments initiated by energy companies varied according to the objective of the cohesion policy. The highest average percentage of EU support was received by projects that were intended to achieve “Objective 02: Increasing the availability, use and quality of information and communication technologies” (this amounted for 85%), while the lowest average percent (54%) involved “Objective 01: Strengthening research, technological development and innovation”. On average, 65% of all project support was received by investments implementing “Objective 07: Promote sustainable transport and address capacity shortfalls in the operation of key network infrastructure” (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average level of project funding by project purpose.

In turn, an analysis of the amounts received by enterprises shows that they received the most money to support the transition to a low-carbon economy (a total of more than PLN 1 billion) and the least under the “Strengthening the competitiveness of small- and medium-sized enterprises” objective (PLN 528 thousand) (Table 5). This distribution is due to the nature of the projects, as hard infrastructure projects require large expenditures, while “soft” projects such as training are characterized by low financial outlays. Of note: 41% of the projects received funding through a competitive process and 58% through a non-competitive one.

Table 5.

Average value of EU funding by project objective.

Objective 04 was implemented by 126 projects which were financed 64% by the Cohesion Fund and 36% by ERDF. Herein, 58 projects were related to electricity storage and transmission, half of the projects concerned renewable energy sources, energy production and distribution, while 23 (18%) projects focused on the development and implementation of intelligent distribution systems operating at low- and medium-voltage levels. The remaining investments under Objective 04 were related to the efficient distribution of heat and cooling, the comprehensive elimination of low emissions in the Silesian Voivodeship and the promotion of the use of highly efficient cogeneration of heat and electricity based on the demand for useful heat.

Twenty-six projects were accomplished under the Intelligent Development Operational Program, and 66% of these involved activities of an innovative nature. Under the Regional Programs, new solutions were enacted related to modernization of medium-voltage lines and increasing energy efficiency, as well as for increasing the potential of ENEA’s power grid to receive energy from renewable sources in the Lubuskie, Wielkopolskie, Zachodniopomorskie and Kujawsko-Pomorskie voivodeship. The projects initiated by the energy companies covered urban units in the main. Most often, the investments were carried out within a single city or town or involved several localities in the same voivodeship. The latter included investments of a network nature.

DB Energy, Veolia and ECO were companies that carried out projects that had an effect upon only a single locality. PEG, in contrast, implemented investments that were often province-wide or involved several localities.

The enacted projects were for the most part infrastructure investments, which involved the construction or reconstruction of the substations or power grids at the disposal of the group. The incorporated innovative solutions and those from the research and development zone were based on developing innovative systems for effective monitoring, supporting protection devices, developing adaptive electricity storage systems based on the second life of batteries from electric vehicles and conducting research and development work aimed at creating an innovative Virtual Power Plant platform allowing aggregation of generation and regulation potential of distributed renewable energy sources. The investigated energy companies also received financial support from the European Union for projects aimed at implementing innovative energy storage system services that were designed to increase the quality and efficiency of electricity use, or for developing decision-support tools for selecting charging technologies for electric buses and locating charging infrastructure.

To sum up, projects of an infrastructural nature aimed at the reconstruction or construction of energy infrastructure elements or increasing the potential of the power grid qualified as being renewable energy source projects. The projects in the research and development zone were usually not of a hard and infrastructural nature because they concerned the performance of R&D work or the development of innovative systems, such as energy storage. Among these endeavors were those that concerned the development of a mathematical model for data processing and the development of a Data Management Platform for advanced metering infrastructure. Hence, projects related to the implementation of innovation and renewable energy sources were thus carried out by the most significant capital groups in the energy market.

5. Discussion

The energy sector in Poland is currently in a state of continuous flux due to the influence of various factors, including those political and economic. As indicated by numerous studies, it requires investment in the direction of shaping a low-carbon economy. In this regard, one important aspect is the provision of financial support for companies operating in the energy sector [66]. In other countries with similar characteristics of energy policy (high centralization), with a wide variety of financial support instruments, the degree of renewable energy use is higher [67]. An example of such a country is Italy, where the energy sector is also at a niche level and is characterized by small initiatives largely dependent on national and external support. Although it has managed to develop a number of projects and diversify its operations there, it is still dependent on financial and political support for investment [68]. As Kazak et al. [69] point out, EU funds in the field of energy management, including the use of RESs, have had different effects on Poland and other countries, such as Italy [68,70,71], Romania [72,73] and the Baltic States [74].

The results of the analysis of Polish companies in terms of how they use EU aid funds for development investments are similar to the situation in Italy, which was studied by [70]. Poland and Italy have already allocated the most EU funds to energy investments since 2007 [47,71]. However, in both countries there was a small share of companies involved in financing this type of investment. That is because these investments seem inherently risky due to the many unknowns associated with future cash flows, such as the price of energy or technological risks [75].

Energy companies, including Polish, no matter their size or location, are obliged to seek and implement innovative solutions at every stage of the delivery of their products or services [76,77]. This is strongly related to reducing their carbon footprint and the mandate emphasizing the use of renewable energy sources [78]. As an outcome, many energy companies around the world are researching the application of information and communication technological developments, including blockchain. Incorporating such technologies is expected to revolutionize the energy industry. Their implementation should lead to energy systems that are in the long run smarter, more efficient, more transparent and safer [79].

The results of a study of EU-funded investments in Polish energy companies do not, however, indicate such a trend. For the most part, infrastructure investments were undertaken, including thermal modernization of enterprise buildings, modernization of heat sources, district heating and electricity networks, and construction of high-efficiency cogeneration units. In addition to these investments, hence, innovative solutions should be incorporated, and related to this, investments in R&D and digitization should occur. This allows Poland’s energy companies to reduce operating costs and increase their efficiency of production.

Thanks to digital advances, the useful life of an energy plant can be extended by up to 30%. Advanced technologies, block-chain and the use of smart grids allow the industry to reduce energy consumption while increasing energy generation efficiency [80]. Such a direction of innovation should also be expected in the Polish power industry. An important direction of action, also financed by EU support, is the decentralization of the sector and the construction of a so-called “prosumer energy industry” based on RESs. It is indicated that this may be the best direction for the transformation of Poland’s energy sector [81]. It is assumed that in the future many electricity consumers in Poland will transform into prosumers, as is the case, for example, in the German market. Moreover, there will be a demand and a place for new, more comprehensive products and services dedicated to particular groups of consumers [82,83]. The need to build public acceptance for such activities has been written about, for example in [84,85,86]. The studies conducted do not confirm investment in such a goal by Polish companies, but it should be stipulated that the need for such activity does not arise from their essence.

Both in the cognitive and applied sense, it can be considered that our research fills a gap existing in the sphere of previous scientific endeavor, and the research problem undertaken deserves in-depth theoretical and empirical studies. Our study noted that large energy companies in Poland spend a small portion of EU support funds on innovative tasks related to the use of RESs and low-carbon energy. This is in contrast to the findings of Sterlacchini [87], who revealed that the decline in research spending was particularly strong among private or newly privatized companies, while those that remained under public control did not reduce research investment. Similarly, the findings of Cortez et al. [88] indicate that abandoning investments in fossil fuels does not negatively affect company financial performance and that investors playing an active role in the transition from high-carbon fossil fuels to renewable and clean energy sources do not necessarily face a trade-off between environmental and financial performance. Such a direction should be included in Poland’s energy policy and the strategies of the companies surveyed. It is recommended that EU funds be spent on environmental practices to minimize damage to the natural environment and quality of life.

The empirical research confirmed the accepted hypothesis that Poland’s largest energy companies are most active in investing in projects aimed at shaping a low-carbon economy co-financed by EU funds, and the most important direction for the use of funds is the modernization or construction of energy infrastructure. Ultimately, it should be recognized that these initiatives are right and properly enacted within the framework of the needs of the energy economy, but it is worthwhile to increase the involvement of companies in the initiation of projects aimed at the creation and use of innovative solutions, as well as the formation of human competence and the building of public awareness of the necessity to derive solutions aimed at reducing the carbon intensity of the economy.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, studies of the use of EU funds by energy sector companies in Poland indicate that these funds were an important instrument for the transition to a low-carbon economy in the period 2014–2020. EU policy objectives thus have accelerated the already inevitable need to modernize and rebuild Poland’s energy infrastructure. The following conclusions emerge from the research and analysis we conducted:

- −

- EU funds have been important in financing investments to decarbonize the economy. However, this did not apply to the sector as a whole but to the main players in the energy market.

- −

- The level of co-financing of investments made by energy companies was high, most often exceeding half of the investment value.

- −

- The surveyed companies, with the support of EU funds, aimed to achieve the objectives of Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council for energy efficiency, primarily concerned with bringing a low-carbon economy into reality.

- −

- Most of the EU support funds have been allocated to infrastructure investments. These are important but insufficient to accelerate the energy transition. A greater share of investments in the research and development sphere would be needed, through which the level of innovation in the energy sector could be raised.

- −

- Projects implemented by companies were closely aligned with the objectives of Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council for energy efficiency and most pursued the objective of supporting the transition to a low-carbon economy. Under this objective, half of the projects involved investments related to renewable energy sources.

- −

- There was little involvement of enterprises in the implementation of projects aimed at creating and using innovative solutions, as well as in shaping human competence and building public awareness of the implementation of solutions to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy,

- −

- Research on financing projects for shaping the low-carbon economy of key players in the energy sector in Poland needs to be continued and developed.

The obtained results suggest the need to continue this line of research by extending it with comparative analysis. The obtained results are not final and are the beginning of further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-S. and A.D.-N.; methodology, E.S.-S., A.D.-N. and A.K.; investigation, E.S.-S. and A.D.-N.; resources, A.D.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-S.; writing—review and editing, E.S.-S.; visualization, A.D.-N. and A.K.; supervision, A.D.-N.; writing—review and editing validation, A.D.-N., E.S.-S. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, A.O. Sustainable Energy Transition for Renewable and Low Carbon Grid Electricity Generation and Supply. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 743114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framework Convention on Climate Change: Adoption of the Paris Agreement, Paris. 2015. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/831039 (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Jankiewicz, S. Gospodarka niskoemisyjna jako podstawa rozwoju regionu. Nierówności Społeczne A Wzrost Gospod. 2017, 49, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglarz, A. Co Kryje się Pod Pojęciem Gospodarki Niskoemisyjnej; Energii, S.A., Ed.; Krajowa Agencja Poszanowania: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EU COM. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions, and the European Investment Bank. Accelerating Clean Energy Innovation. European Commission (EU COM): Brussels, Belgium, 2016, 763 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0763&rid=4 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Szyja, P. Transition to a Low Carbon Economy at the Level of Local Government. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2016, 437, 447–463. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G. The governance of innovations in the energy sector: Between adaptation and exploration. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2014, 27, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovation Policy. Fact Sheets on the European Union, European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_2.4.6.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Energy Policy: General Principles. Fact Sheets on the European Union, European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/pl/FTU_2.4.7.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- EU COM. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank a framework Strategy for a Sustainable Energy Union Based on a Forward-Looking Climate Policy; European Commission (EU COM): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Standar, A.; Kozera, A.; Satoła, Ł. The Importance of Local Investments Co-Financed by the European Union in the Field of Renewable Energy Sources in Rural Areas of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, A.; Satoła, Ł.; Standar, A.; Dworakowska-Raj, M. Regional diversity of low-carbon investment support from EU funds in the 2014–2020 financial perspective based on the example of Polish municipalities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Gerstlberger, W. Financing Responsible Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: An International Overview of Policies and Support Programmes. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, W.J.; Rakowska, J. Review of Regional Renewable Energy Investment Projects: The Example of EU Cohesion Funds Dispersal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, E.; Arsenopoulos, A. Investigating EU financial instruments to tackle energy poverty in households: A SWOT analysis. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2019, 14, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P.; Rezessy, S.; Vine, E. Energy service companies in European countries: Current status and a strategy to foster their development. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1818–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; McGee, J.A. Understanding the Jevons paradox. Environ. Sociol. 2016, 2, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Jevons’ Paradox revisited: The evidence for backfire from improved energy efficiency. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1456–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, D. What is Low-Carbon Development? A Conceptual Analysis. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradziuk, P.; Gradziuk, B. Gospodarka niskoemisyjna–nowe wyzwanie dla gmin wiejskich. Wieś I Rol. 2016, 1, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baleta, J.; Mikulcic, H.; Klemeš, J.J.; Urbaniec, K.; Duic, N. Integration of energy, water and environmental systems for a sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.A.; Papadopoulou, M.P.; Laspidou, C.; Munaretto, S.; Brouwer, F. Towards a Low-Carbon Economy: A Nexus-Oriented Policy Coherence Analysis in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Yuding, W.; Jianzhong, W. The Problems and Strategies of the Low Carbon Economy Development. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, D.R. Global Future: Low-Carbon Economy or High-Carbon Economy? World 2021, 2, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Decade of EVALUATION for Action to Deliver the SDGs by 2030. United Nations (UN) Campaign Concept Note; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Decade of Action—United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/decade-of-action/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- 2030 Climate & Energy Framework. Climate Action. European Commision. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2030_pl (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- 2020 Climate & Energy Package. Climate Action. European Commision. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2020-climate-energy-package_en (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Allen, M.L.; Allen, M.M.C.; Cumming, D.; Johan, S. Comparative Capitalisms and Energy Transitions: Renewable Energy in the European Union. Br. J. Manag. 2021, 32, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, D.; Gibbs, D.C.; Longhurst, J.W.S. The employment implications of a low-carbon economy. Sustain. Dev. 2000, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G.; Bouzarovski, S.; Bradshaw, M.; Eyre, N. Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy. Energy Policy 2013, 53, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, M.; De Cian, E.; Luderer, G.; Steckel, J.C.; Waisman, H. The value of technology and of its evolution towards a low carbon economy. Clim. Chang. 2011, 114, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupik, S.; Kos-Łabędowicz, J.; Trzesiok, J. Energy-Related Behaviour of Consumers from the Silesia Province (Poland) Towards a Low-Carbon Economy. Energies 2021, 14, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, B.; Domaracká, L.; Tobór-Osadnik, K. Innovative Activity of Companies in the Raw Material Industry on the Example of Poland and Slovakia—Selected Aspects. J. Pol. Miner. Eng. Soc. 2020, 2, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Standar, A.; Kozera, A.; Jabkowski, D. The Role of Large Cities in the Development of Low-Carbon Economy—The Example of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, F.; Sandoval, S.I. European Energy Policy; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miciuła, I. Polityka energetyczna Unii Europejskiej do 2030 roku w ramach zrównoważonego rozwoju. Stud. I Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. I Zarządzania 2015, 42, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Arriaga, I. Regulation of the Power Sector. In Loyola de Palacio Series on European Energy Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leveque, F.; Glachant, J.M.; Barquin, J.; Holz, F.; Nuttall, W. Security of Energy Supply in Europe Natural Gas, Nuclear and Hydrogen. In Loyola de Palacio Series on European Energy Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paska, J.; Surma, T. “Pakiet Zimowy” Komisji Europejskiej a kierunki i realizacja polityki energetycznej do 2030 roku. Rynek Energii 2017, 2, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Paska, J.; Surma, T. Wpływ polityki energetycznej Unii Europejskiej na funkcjonowanie przedsiębiorstw energetycznych w Polsce. Rynek Energii 2016, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Korbutowicz, T. Polityka pomocy publicznej UE w odniesieniu do energii. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2018, XIX/ 2, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Regulation (EU). No 651/2014 of 17 June 2014 Declaring Certain Categories of Aid Compatible with the Internal Market in Application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty Text with EEA Relevance. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2014:187:FULL&from=IT (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Official Journal of the European Union C 200. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2018:200:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Janowski, K. Mechanizmy finansowania inwestycji energetycznych ze źródeł europejskich. Rynek Energii 2011, 3, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- EU COM. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Financial Support for Energy Efficiency in Buildings; COM: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Volume 225, Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0225&from=CS (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Kochański, M. Finansowanie instrumentów poprawy efektywności energetycznej w Polsce w latach 2014–2020. Acta Innov. 2014, 10, 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2012/27/Eu of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 25 October 2012, on Energy Efficiency, Amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and Repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32012L0027&from=EN (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Operational Program Infrastructure and Environment 2007–2013, National Strategic Reference Framework 2007–2013, version 5.0. Available online: https://www.pois.gov.pl/media/92372/POIS_2007_2013_wersja_5_0.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Operational Program Infrastructure and Environment 2014–2020, Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy, Version 24.0. 2022. Available online: https://www.pois.gov.pl/media/110770/POIiS_v_24_0.docx (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Grabiec, O. Charakterystyka i funkcjonowanie grup kapitałowych polskiego sektora energetycznego. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Humanitas. Zarządzanie 2009, 2, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Policy of Poland until 2030, Ministry of Economy, Warsaw, 10 November 2009 r. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WMP20210000264/O/M20210264.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Finansowanie Inwestycji Energetycznych w Polsce; Pricewaterhouse Coopers i ING Bank Śląski: Warsaw, Poland, 2011.

- Lipski, M. Wyzwania sektora energetycznego w Polsce z perspektywy akcjonariuszy. Zesz. Nauk. PWSZ W Płocku Nauk. Ekon. 2016, XXIII, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, J.; Czerwonka, L. Determinants of Enterprises’ Capital Structure in Energy Industry: Evidence from European Union. Energies 2021, 14, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabińska, B.; Kędzior, M.; Kędzior, D.; Grabiński, K. The Impact of Corporate Governance on the Capital Structure of Companies from the Energy Industry. Case Pol. Energy 2021, 14, 7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk-Ściebura, K.; Olkuski, T. Wdrażanie polityki klimatyczno-energetycznej w TAURON POLSKA ENERGIA SA. Polityka Energetyczna 2016, 19, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Local Data Bank. Central Statistical Office: Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/dane/podgrup/temat (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- National Court Register. Available online: https://ekrs.ms.gov.pl/web/wyszukiwarka-krs/strona-glowna/index.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- National Report of the President of the Energy Regulatory Authority 2015. Available online: file:///C:/Users/Agnieszka/Downloads/Raport_Roczny_Prezesa_URE_-_2015-1.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- National Report of the President of the Energy Regulatory Authority 2020. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/download/9/11395/Raport2020.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Electricity and Gas Market in Poland Report TOE. 2022. Available online: https://toe.pl/pl/wybrane-dokumenty/rok-2022?download=1601:rynek-energii-elektrycznej-i-gazu-w-polsce-stan-na-31-marca-2022-raport-toe (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Database of Implemented EU Projects; Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy: Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/media/112582/Lista_projektow_FE_2014_2020_011222.xlsx (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Pakuła, J. Raport sektorowy—energetyka. Profit J. Mag. Finans. 2020, 31. Available online: https://profit-journal.pl/raport-sektorowy-energetyka/ (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Jarosz, S.; Gawlik, K.; Gozdecki, K. Pozyskanie Finansowania Dla Działalności Przedsiębiorstw—Analiza Sektora Energetycznego. Zarządzanie I Jakość 2022, 4, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cucchiella, F.; Condemi, A.; Rotilio, M.; Annibaldi, V. Energy Transitions in Western European Countries: Regulation Comparative Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelise, C.; Ruggieri, G. Status and Evolution of the Community Energy Sector in Italy. Energies 2020, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, J.K.; Kamińska, J.A.; Madej, R.; Bochenkiewicz, M. Where Renewable Energy Sources Funds are Invested? Spatial Analysis of Energy Production Potential and Public Support. Energies 2020, 13, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bointner, R.; Pezzutto, S.; Grilli, G.; Sparber, W. Financing innovations for the renewable energy transition in Europe. Energies 2016, 9, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A.; Romano, A.A.; Ronghi, M.; Scandurra, G. Renewable generation across Italian regions: Spillover effects and effectiveness of European Regional Fund. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostan, I.; Lazar, C.M.; Asalos, N.; Munteanu, I.; Horga, G.M. The three-dimensional impact of the absorption effects of European funds on the competitiveness of the SMEs from the Danube Delta. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 132, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostan, I.; Moroşan, A.A.; Hapenciuc, C.V.; Stanciu, P.; Condratov, I. Are Structural Funds a Real Solution for Regional Development in the European Union? A Study on the Northeast Region of Romania. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Klevas, V.; Bubeliene, J. Use of EU structural funds for sustainable energy development in new EU member states. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1167–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexis, F.D.; Papapostolou, A.; Karakosta, C.; Psarras, J.; Psarras, J. Financing Sustainable Energy Efficiency Projects: The Triple-A Case. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, F.; Rogge, K.S.; Howlett, M. Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: New approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, K. Finansowanie inwestycji w energetykę odnawialną i poprawę efektywności energetycznej—atrakcyjność, ryzyko, bariery. Pr. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Bank. W Gdańsku 2013, 27, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of eco-innovations: Reflections from selected case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, A.; Verma, P.; Southernwood, L.; Massey, B.; Corcoran, P. Blockchain in Energy Effciency: Potential Applications and Benefits. Energies 2019, 12, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Digitization, Digital Twins, Blockchain, and Industry 4.0 as Elements of Management Process in Enterprises in the Energy Sector. Energies 2021, 14, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretek, H. Przyszłość energetyki w Polsce w drodze transformacji ku OZE. Etyka Bizn. I Zrównoważony Rozw. Interdyscyplinarne Stud. Teor. Empiryczne 2018, 1, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thon, F. Energetyka Potrzebuje “Nowej Pary Oczu”. Przyszłość to Innowacje. Available online: http://www.rp.pl/artykul/1163332-Energetyka-potrzebuje-nowej-pary-oczu-Przyszlosc-to-innowacje.html (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Zawada, M.; Pabian, A.; Bylok, F.; Chichobłaziński, L. Innowacje w sektorze energetycznym. Res. Rev. Czest. Univ. Technol. Manag. 2015, 19, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wolsink, M. Distributed energy systems as common goods: Socio-political acceptance of renewables in intelligent microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 127, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neska, E.; Kowalska-Pyzalska, E. Conceptual design of energy market topologies for communities and their practical applications in EU: A comparison of three case studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parag, Y.; Sovacool, B. Electricity market design for the prosumer era. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16032–16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterlacchini, A. Energy R&D in private and state-owned utilities: An analysis of the major world electric companies. Energy Policy 2012, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.C.; Andrade, N.; Silva, F. The environmental and financial performance of green energy investments: European evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 197, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).