Exploring the User Adoption Mechanism of Green Transportation Services in the Context of the Electricity–Carbon Market Synergy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Consumer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention

2.2. Risk Perception and Repurchase Intention

2.3. Sustainability Awareness and Repurchase Intention

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures and Questionnaire Development

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Reliability and Validity

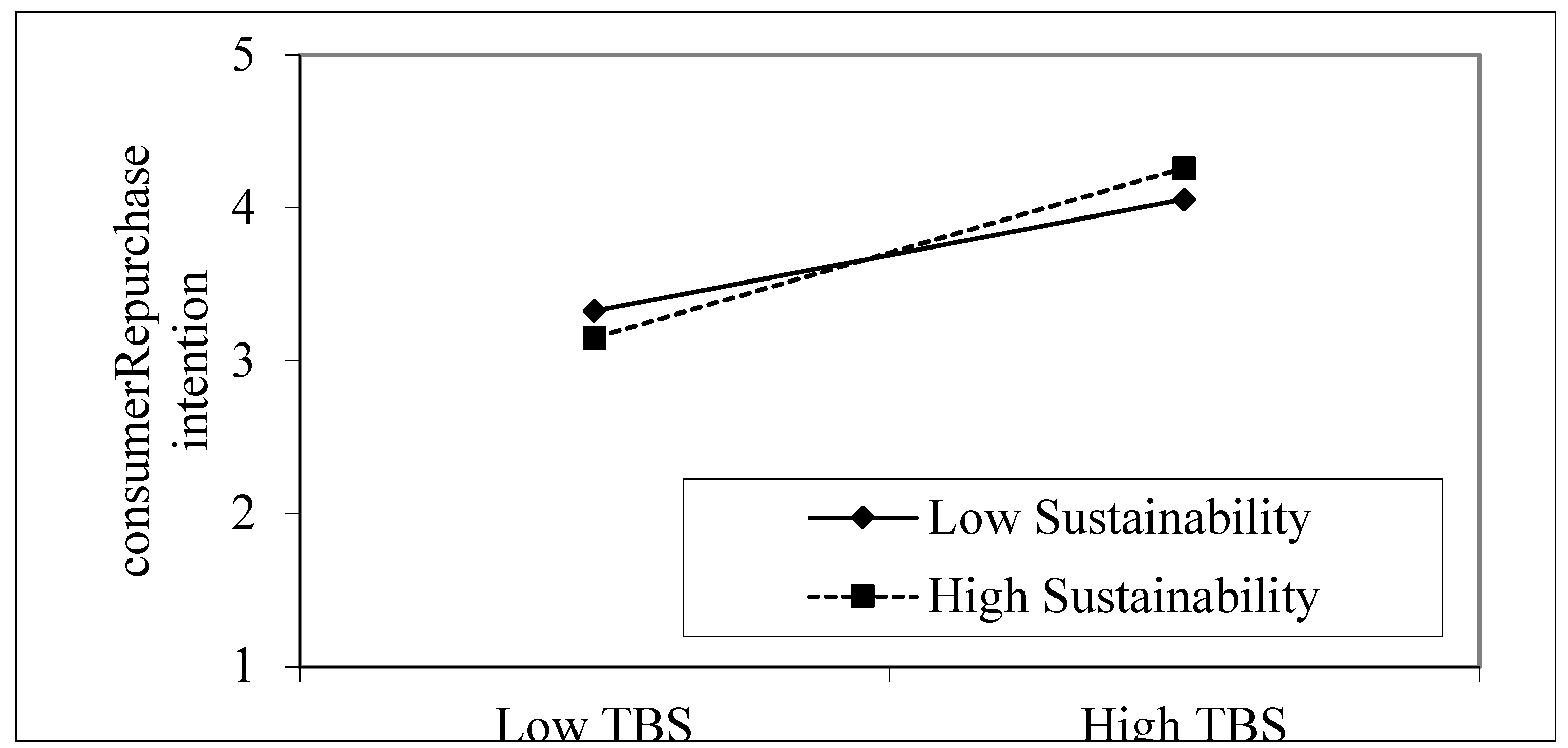

4.2. Hypothesis Testing and Result Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huo, W.; Qi, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Z. Effects of China’s pilot low-carbon city policy on carbon emission reduction: A quasi-natural experiment based on satellite data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A.; Alnour, M.; Jahanger, A.; Onwe, J.C. Do technological innovation and urbanization mitigate carbon dioxide emissions from the transport sector? Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Bianco, V.; Barth, H.; Pereira da Silva, P.; Vargas Salgado, C.; Pallonetto, F. Technologies and Strategies to Support Energy Transition in Urban Building and Transportation Sectors. Energies 2023, 16, 4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, T.T.; Liu, L.L.; Zhang, M.X. How do the electricity market and carbon market interact and achieve integrated development?—A bibliometric-based review. Energy 2023, 265, 126308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.J.; Gleim, M.R.; Perren, R.; Hwang, J. Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhi, Q. Impact of shared economy on urban sustainability: From the perspective of social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Energy Procedia 2016, 104, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.P.; Rose, R.L. When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, A. From Zipcar to the sharing economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.J. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s mine is yours. In The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Tantor Audio: Old Saybrook, CT, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.A. Intermediation in a sharing economy: Insurance, moral hazard, and rent extraction. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 31, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C.; Lutz, C. What’s mine is yours (for a nominal fee)—Exploring the spectrum of utilitarian to altruistic motives for Internet-mediated sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.; Smith, S.; Potwarka, L.; Havitz, M. Why tourists choose Airbnb: A motivation-based segmentation study. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ert, E.; Fleischer, A.; Magen, N. Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, B.; Cleveland, S. The future of hotel chains: Branded marketplaces driven by the sharing economy. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Wu, J.J.; Chung, Y.S. Cultural impact on trust: A comparison of virtual communities in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2008, 11, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Limayem, M.; Liu, V. Online customer stickiness: A longitudinal study. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 2002, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, E.R. The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment–trust theory and e-commerce success model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, P.; Horner, D.; Pemberton, L. Factors contributing to adoption and use of information and communication technologies within research collaborations in Kenya. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S1), 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, D.; Hahn, R. Does shared consumption affect consumers’ values, attitudes, and norms? A panel study. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; Wensley, R. Marketing theory with a strategic orientation. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.A.; Malech, A.R. Handbook of Modern Marketing; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T.S.; Cui, G.; Cui, G. Consumer attitudes toward marketing in a transitional economy: A replication and extension. J. Consum. Mark. 2004, 21, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuwichanont, J.; Mechinda, P.; Serirat, S.; Lertwannawit, A.; Popaijit, N. Environmental sustainability in the Thai hotel industry. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2011, 10, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.T.B.; Wu, D.D. Online banking performance evaluation using data envelopment analysis and principal component analysis. Comput. Oper. Res. 2009, 36, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Tian, L. Collaborative consumption: Strategic and economic implications of product sharing. Manag. Sci. 2016, 64, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gu, G.; An, S.; Zhou, G. Understanding online consumer stickiness in e-commerce environment: A relationship formation model. Int. J. u- e-Serv. Sci. Technol. 2014, 7, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.; Puchinger, J.; Chu, C. A survey of models and algorithms for optimizing shared mobility. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 123, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence customer loyalty. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Baker, T.L.; Bolton, R.N.; Gruber, T.; Kandampully, J. A triadic framework for collaborative consumption (CC): Motives, activities and resources & capabilities of actors. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.; Wilson, W. Measuring customer satisfaction: Fact and artifact. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M.A.; Miceli, G.; Costabile, M. How Relationship Age Moderates Loyalty Formation: The Increasing Effect of Relational Equity on Customer Loyalty. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 11, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Fornell, C. A framework for comparing customer satisfaction across individuals and product categories. J. Econ. Psychol. 1991, 12, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, V.; Vladimir, S.; Obradović, S.; Šapić, S. Understanding antecedents of customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth communication: Evidence from hypermarket chains. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 8515–8524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahagun, M.A.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z. Can fast-food consumers be loyal customers, if so how? Theory, method and findings. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselius, T. Consumer rankings of risk reduction methods. J. Mark. 1971, 35, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.C.; Harlow, W.V.; Tinic, S.M. Risk aversion, uncertain information, and market efficiency. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 22, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Institutional pressures and environmental management practices: The moderating effects of environmental commitment and resource availability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M.; King, N.; Harris, M.; Lewis, E. Electric vehicle drivers’ reported interactions with the public: Driving stereotype change? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 17, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.M.; Stracca, L. Getting beyond carry trade: What makes a safe haven currency? J. Int. Econ. 2012, 87, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, H.E.; Ozanne, L.K.; Ballantine, P.W. Examining temporary disposition and acquisition in peer-to-peer renting. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 1310–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J. Assessing Economic Value of Reducing Perceived Risk in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Ride-Sharing Services; AIS Electronic Library: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Lyu, J. Why travelers use Airbnb again? An integrative approach to understanding travelers’ repurchase intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2464–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, Lugano, Switzerland, 3–6 February 2015; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E. Do greens drive Hummers or hybrids? Environmental ideology as a determinant of consumer choice. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 54, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Understanding current and future issues in collaborative consumption: A four-stage Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 104, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.J.; Choi, H.C.; Joppe, M. Understanding repurchase intention of Airbnb consumers: Perceived authenticity, electronic word-of-mouth, and price sensitivity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Sherk, M. Institutional pressures and product modularity: Do supply chain coordination and functional coordination matter? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 6644–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Statistical power with moderated multiple regression in management research. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frör, O. Bounded rationality in contingent valuation: Empirical evidence using cognitive psychology. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Information Center. China’s Sharing Economy Development Report. 2023. Available online: http://www.sic.gov.cn/News/79/8860.htm (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Zhang, T.C.; Gu, H.; Jahromi, M.F. What makes the sharing economy successful? An empirical examination of competitive customer value propositions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Bhatnagar, A.; Rao, H.R. Assurance seals, on-line customer satisfaction, and repurchase intention. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2010, 2010, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, I.; Agag, G. E-retailing ethics and its impact on customer satisfaction and repurchase intention: A cultural and commitment-trust theory perspective. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delistavrou, A.; Tilikidou, I.; Papaioannou, E. Climate change risk perception and intentions to buy consumer packaged goods with chemicals containing recycled CO2. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkowski, O.K.; Pakseresht, A.; Lagerkvist, C.J.; Bröring, S. Debunking the myth of general consumer rejection of green genetic engineering: Empirical evidence from Germany. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Rjoub, H.; Yesiltas, M. Environmental awareness and guests’ intention to visit green hotels: The mediation role of consumption values. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustam, A.; Wang, Y.; Zameer, H. Environmental awareness, firm sustainability exposure and green consumption behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Transaction-based satisfaction (TBS) | TBS1. I was satisfied with the recent transaction process with the Didi Chuxing platform. | Marinković et al. (2012) [45]; Sahagun and Vasquez-Parraga (2014) [46]; Liang, Choi, and Joppe (2018) [62] |

| TBS2. I am satisfied with the mechanism of Didi Chuxing. | ||

| TBS3. When I used Didi Chuxing to travel, the driver was polite to me. | ||

| TBS4. When I used Didi Chuxing to travel, the driver provided professional services to me. | ||

| Experience-based satisfaction (EBS) | EBS1. Overall, I am pleased with my experience using Didi Chuxing to travel. | Möhlmann (2015) [8]; Liang, Choi, and Joppe (2018) [62] |

| EBS2. My experience with Didi Chuxing is pleasurable. | ||

| EBS3. The last use of Didi Chuxing fulfilled my expectations. | ||

| EBS4. My choice to use Didi Chuxing to travel was a wise one. | ||

| Risk perception (RP) | RP1. When I use Didi Chuxing to travel, the security system designed by the Didi Chuxing platform makes me feel safe. | Pavlou (2003) [63]; Kim, Ferrin, and Rao (2008) [49]; Hong (2017) [54] |

| PR2. When I used Didi Chuxing to travel, I did not have to worry about waiting too long for service. | ||

| PR3. When I used Didi Chuxing to travel, I was concerned that the platform might sell my personal information to others without my permission. | ||

| RP4. I feel secure about the electronic payment system of the Didi Chuxing platform. | ||

| Sustainability awareness (SA) | SA1. Ride-sharing services such as Didi Chuxing are a sustainable mode of travel. | Tussyadiah (2015) [57]; Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen (2016) [5]; Lawson, Gleim, Perren, and Hwang (2016) [6] |

| SA2. Ride-sharing services help reduce environmental pollution. | ||

| SA3. Ride-sharing services such as Didi Chuxing are environmentally friendly. | ||

| SA4. Ride-sharing services such as Didi Chuxing to travel will be beneficial to save energy. | ||

| Consumer repurchase intention (CRI) | CRI1. I am likely to choose ride-sharing services such as Didi Chuxing to travel or a similar sharing option the next time. | Lamberton and Rose (2012) [10]; Möhlmann (2015) [8]; Liang, Choi, and Joppe (2018) [62] |

| CRI2. In the future, I would prefer a ride-sharing service option like Didi Chuixng for my car. | ||

| CRI3. In the future, I would likely choose a ride-sharing service option like Didi Chuxing instead of my car. |

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 208 | 58.1 |

| Female | 150 | 41.9 |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 14 | 3.9 |

| 21–30 | 176 | 49.2 |

| 31–40 | 122 | 34.1 |

| 41–50 | 34 | 9.5 |

| 51 or above | 12 | 3.4 |

| Education level | ||

| Senior high school or below | 4 | 1.1 |

| Upper secondary | 12 | 3.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree or sub-degree | 158 | 44.1 |

| Master’s degree or above | 184 | 51.4 |

| Annual income (RMB) | ||

| Below 30,000 | 110 | 30.7 |

| 30,001–50,000 | 52 | 14.5 |

| 50,001–80,000 | 64 | 17.9 |

| Above 80,000 | 132 | 36.9 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha Value | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBS | TBS1 | 0.78 *** | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.70 |

| TBS2 | 0.86 *** | ||||

| TBS3 | 0.84 *** | ||||

| TBS4 | 0.86 *** | ||||

| EBS | EBS1 | 0.81 *** | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| EBS2 | 0.80 *** | ||||

| EBS3 | 0.82 *** | ||||

| EBS4 | 0.79 *** | ||||

| RP | RP1 | 0.80 *** | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| RP2 | 0.85 *** | ||||

| RP3 | 0.74 *** | ||||

| SA | SA1 | 0.85 *** | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| SA2 | 0.88 *** | ||||

| SA3 | 0.90 *** | ||||

| SA4 | 0.87 *** | ||||

| CRI | CRI1 | 0.91 *** | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.79 |

| CRI2 | 0.90 *** | ||||

| CRI3 | 0.86 *** |

| Construct | Mean | SD | TBS | EBS | RP | SA | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBS | 3.50 | 0.73 | 0.84 | ||||

| EBS | 3.71 | 0.60 | 0.47 ** | 0.81 | |||

| RP | 2.81 | 0.66 | −0.10 * | −0.18 ** | 0.80 | ||

| SA | 3.60 | 0.72 | 0.38 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.04 | 0.88 | |

| CRI | 3.35 | 0.80 | 0.41 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.10 * | 0.14 * | 0.89 |

| Dependent Variable: Consumer Repurchase Intention (CRI) | VIF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | −0.038 | −0.0032 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 1.172 |

| Age | −0.031 | −0.016 | −0.024 | −0.009 | 1.442 |

| Education | −0.070 | −0.074 | −0.048 | −0.057 | 1.416 |

| Income | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.037 | 0.033 | 1.627 |

| Independent variables | |||||

| TBS | 0.272 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.339 *** | 0.339 *** | 1.500 |

| EBS | 0.293 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.315 ** | 0.269 ** | 1.588 |

| Moderator variables | |||||

| RP | −0.017 | 0.080 | 1.120 | ||

| SA | −0.074 | −0.018 | 1.449 | ||

| Interacting effects | |||||

| TBS*RP | −0.144 ** | −0.158 ** | 1.137 | ||

| EBS*RP | −0.152 ** | −0.134 ** | 1.184 | ||

| TBS*SA | 0.104 ** | 0.107 * | 2.165 | ||

| EBS*SA | −0.019 | −0.042 | 2.176 | ||

| R2 | 0.242 | 0.291 | 0.264 | 0.312 | |

| Adjust R2 | 0.229 | 0.273 | 0.245 | 0.288 | |

| F-value | 18.656 *** | 15.860 *** | 13.898 *** | 13.028 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, D.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Wu, F. Exploring the User Adoption Mechanism of Green Transportation Services in the Context of the Electricity–Carbon Market Synergy. Energies 2024, 17, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17010274

Pan D, Wang B, Li J, Wu F. Exploring the User Adoption Mechanism of Green Transportation Services in the Context of the Electricity–Carbon Market Synergy. Energies. 2024; 17(1):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17010274

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Dong, Bao Wang, Jun Li, and Fei Wu. 2024. "Exploring the User Adoption Mechanism of Green Transportation Services in the Context of the Electricity–Carbon Market Synergy" Energies 17, no. 1: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17010274