Looking at Economics through the Eyes of Thermodynamics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- The number of units of merchandise and money (with intrinsic value, and thus of economic interest) of an economic system is one of its properties;

- -

- The accounting of the number of units of merchandise and money in the economic system leads to the units balance equation, which is the proposed economic counterpart of the First Law balance equation;

- -

- The merchandise (goods and services) transfers by trading occur in the decreasing economic temperature direction, driven by economic temperature differences, without generating new/additional merchandise units in the trading operation but generating economic entropy (generating financial value, or profit). This analogy comes from Thermodynamics, as heat transfers occur in the decreasing temperature direction, driven by temperature differences, without generating new/additional units of energy but generating entropy [1,2,3];

- -

- The one-way merchandise trading in the decreasing economic temperature direction and the economic entropy (financial value) generation in trading operations lead to the proposed Economics counterpart of the Second Law. Economic entropy (financial value) generation is the economic analog of entropy generation in Thermodynamics;

- -

- The economic entropy (the financial value) of an economic system is one of its properties;

- -

- The accounting of the economic entropy (the financial value) of an economic system leads to the economic entropy balance equation, which is the proposed economic counterpart of the Second Law balance equation.

- -

- Temperature and thermal equilibrium (economic temperature and economic equilibrium);

- -

- Heat reservoir (merchandise reservoir);

- -

- Energy and energy transfer interactions (units and units transfer interactions);

- -

- The First Law and the energy balance equation (the economic First Law and the units balance equations);

- -

- Heat transfer through a finite temperature difference (merchandise transfer by trading through a finite economic temperature difference);

- -

- Reversibility, irreversibility, and spontaneity (economic reversibility, economic irreversibility, and economic spontaneity);

- -

- Entropy and entropy generation (economic entropy (financial value) and economic entropy generation);

- -

- The Second Law and the entropy balance equation (the economic Second Law and the economic entropy balance equation);

- -

- Friction and irreversibility (economic friction and economic irreversibility).

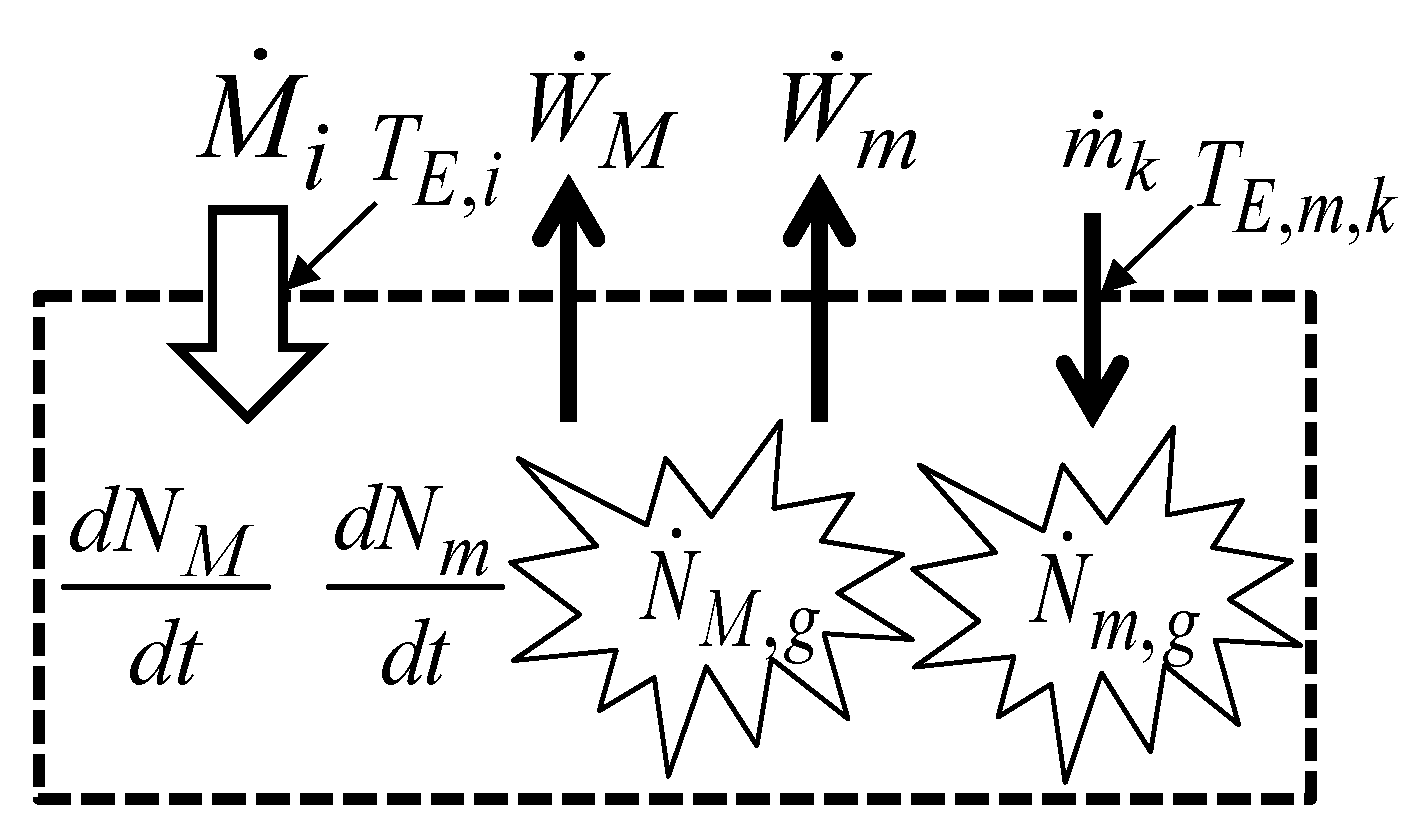

2. The First Law and the Units Balance Equations

2.1. Concepts and Definitions

2.2. Merchandise and Money Transfer Interactions

- -

- Merchandise (goods or services) traded, [U/s]: the number of merchandise units in transit per unit of time (which may be composed of merchandise flow rates [U/s] of different merchandise species i) driven by a potential (economic temperature difference), [U/s] flowing spontaneously in the decreasing economic temperature direction. These are merchandise units that are in the market. The economic temperature at which [U/s] crosses the economic system’s boundary is of major relevance. The economic temperature will be defined in Section 3.1.

- -

- Merchandise wealth, [U/s]: the number of merchandise units in transit per unit of time (which may be composed of merchandise wealth flow rates [U/s] of different merchandise species i) not driven by any potential and thus not being transferred by trading reasons/motivations. These are merchandise units that are not in the market. Consider, for example, a loaded truck, the load being (tradable) merchandise but not the truck itself (which, in this sense, is merchandise wealth). In a different context, the truck can itself be tradable merchandise.

- -

- Monetary wealth, [U/s]: the number of monetary units in transit per unit of time (which may be composed of monetary wealth flow rates [U/s] of different monetary species k) not driven by a potential. These are monetary units not used in the market operations, not being exchanged for merchandise units in the purchasing and selling operations.

- -

- Monetary transfer, [U/s]: the number of monetary units in transit per unit of time (which may be composed of monetary flow rates [U/s] of different monetary species k) not driven by a potential. These are monetary units in the market, used in the market operations and exchanged for merchandise units in the purchasing and selling operations.

2.3. The Units Balance Equations

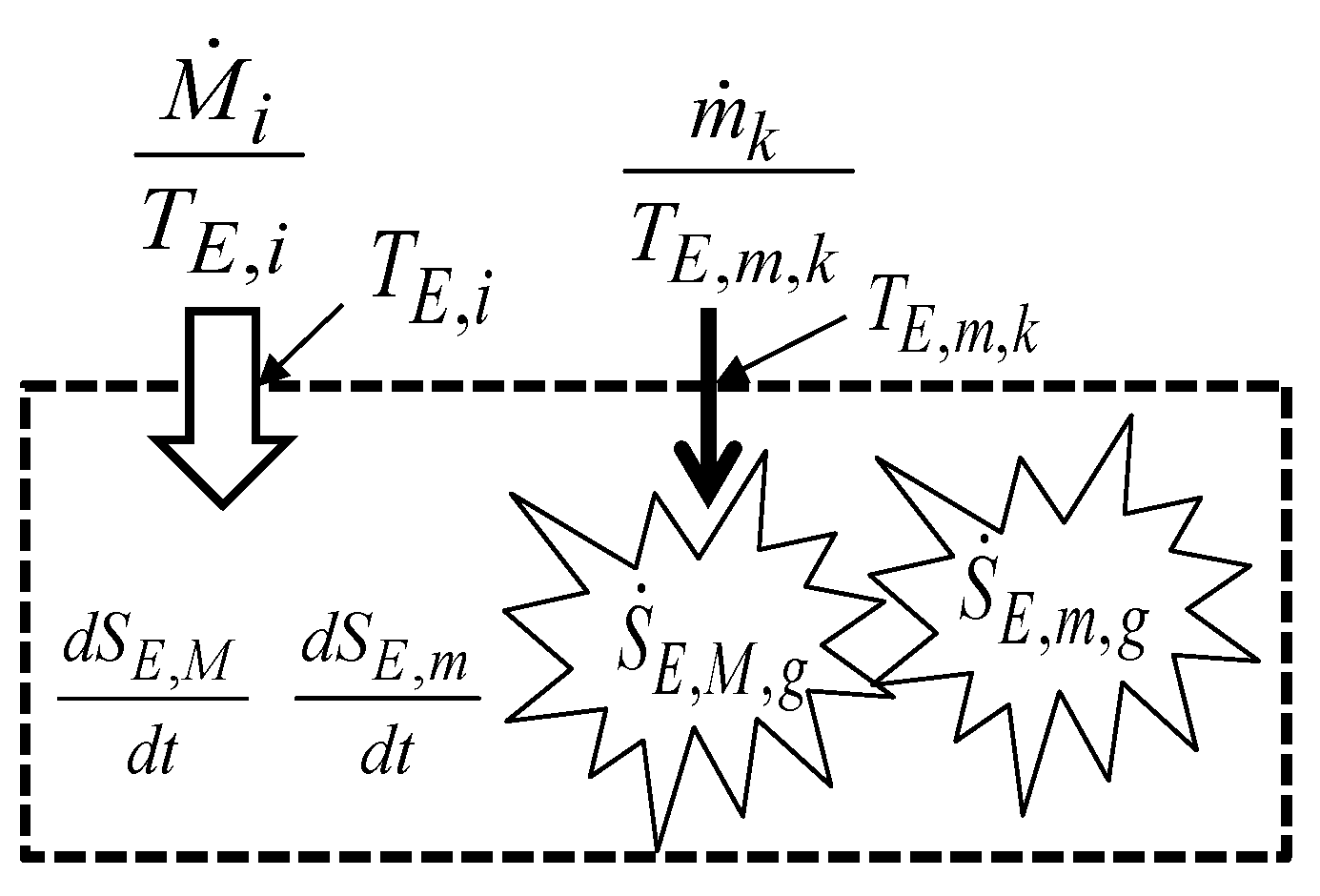

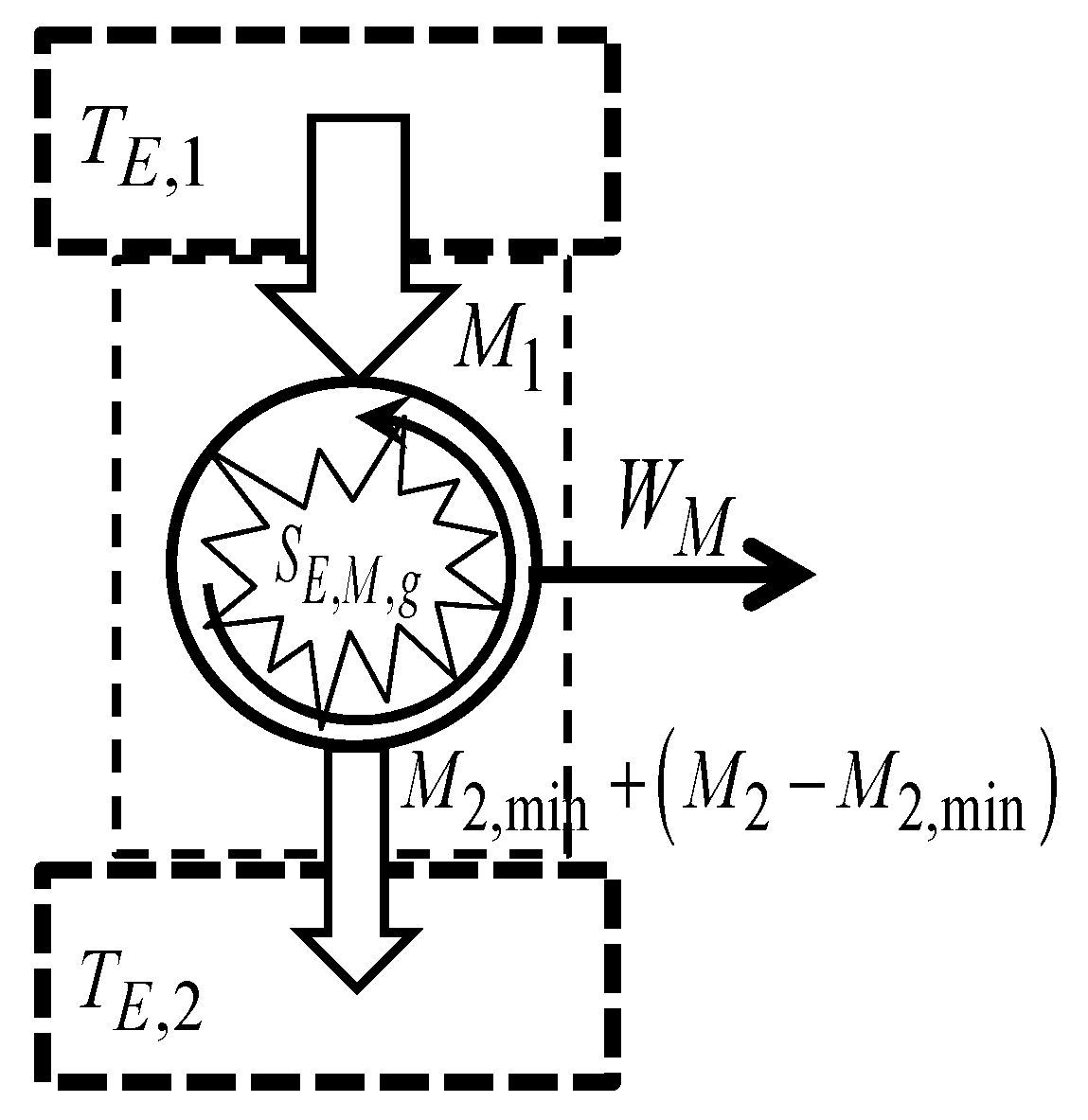

3. The Second Law and the Economic Entropy Balance Equations

3.1. The Meaning of the New Concepts and Variables Involved in the Economic Entropy Balance Equations

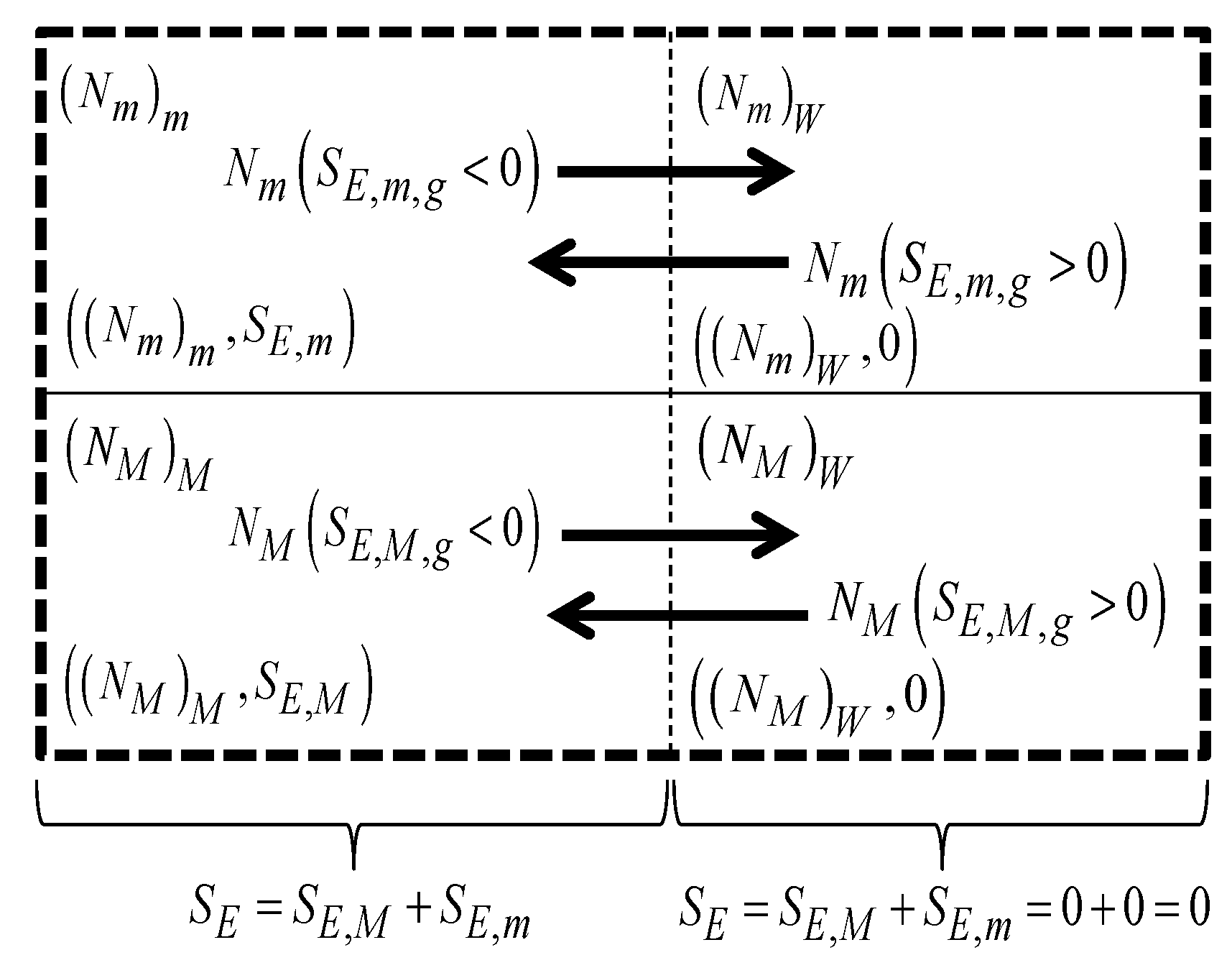

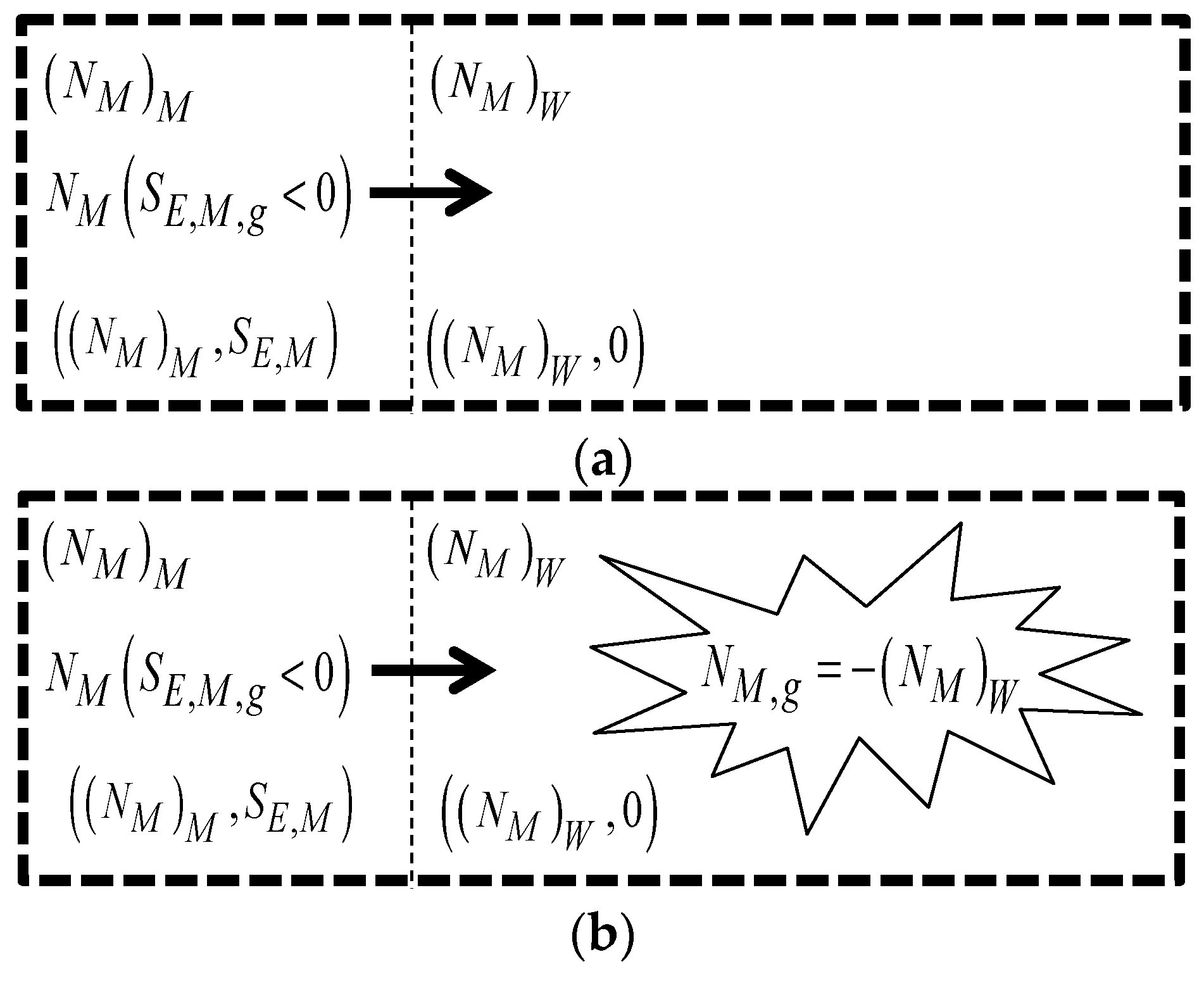

3.2. The Economic Entropy Balance Equations

3.3. Merchandise Transfers Motivated by Trading and Arbitrary Decisions

3.4. Naturally Driven Economic Operations and Arbitrary Decisions

3.5. End User and Final Consumer

3.6. Some Challenging Reflections

- -

- -

- Should economic thinking and decision-making be based increasingly more on the First Law of Economics and less on its Second Law? In some ways of life, such as those of small farms and villages, exchanging products with the neighbors, helping each other free of charge, sharing tools, manpower, and non-paid labor, exchanging goods and avoiding purchasing and selling, thus avoiding using money and trading operations, are efforts in that direction (emphasis on the number of units rather than on economic entropy and financial value).

- -

- Should the entropy generation minimization criterion be taken as the headlight of both Thermodynamics and Economics?

- -

- Merchandise transfers (First Law of Economics) in trading operations have their associated merchandise economic entropy transfers (Second Law of Economics), which have their associated monetary economic entropy transfers and their respective monetary units transfers (a third species involved in the trading operations). Heat transfers (First Law) have their associated entropy transfers (Second Law), but there is no third species involved to reward the entropy donor and receive from the entropy receiver. Entropy transfers seem to be intangible and not accompanied by any species of entropic money. Should we set ‘thermy’ as the thermodynamic analog of money in Economics to reward the entropy donor and receive from the entropy receiver, to pay for the received entropy?

- -

- Banks have business models based on monetary financial values, that is, based on monetary economic entropy. Perhaps in the future, they, or other organizations, will have their analog business models based on (thermodynamic) entropy, using entropic counters and ‘thermies’.

3.7. Concluding Remarks

4. Trading as Merchandise Exchange for Money

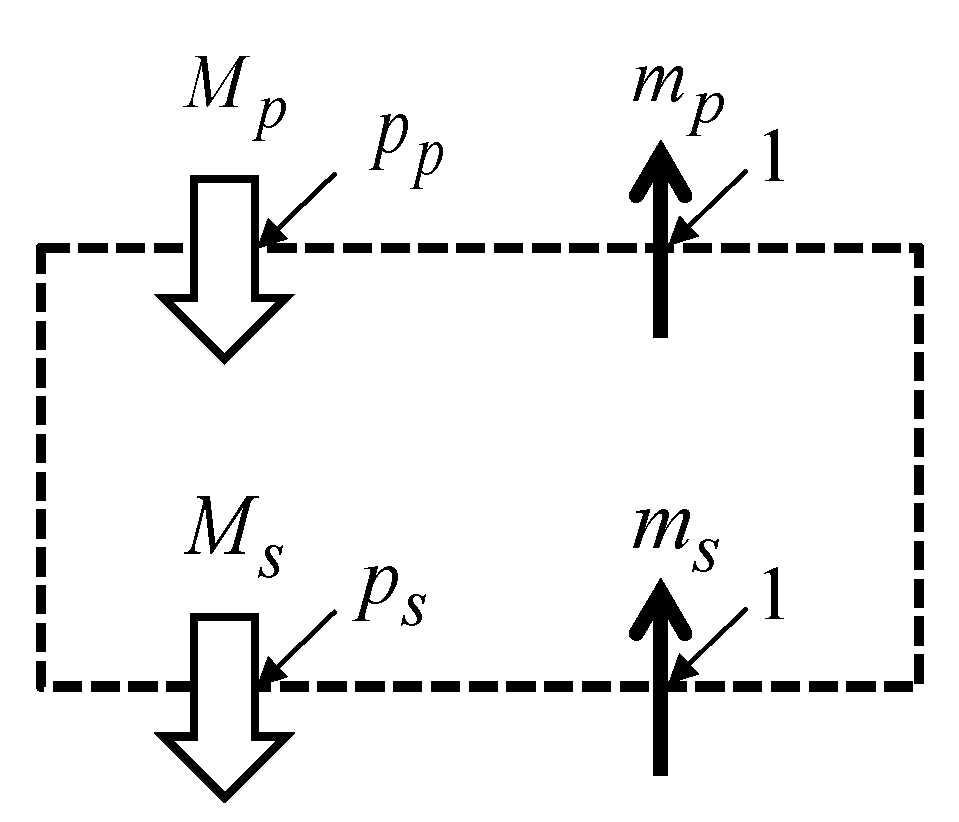

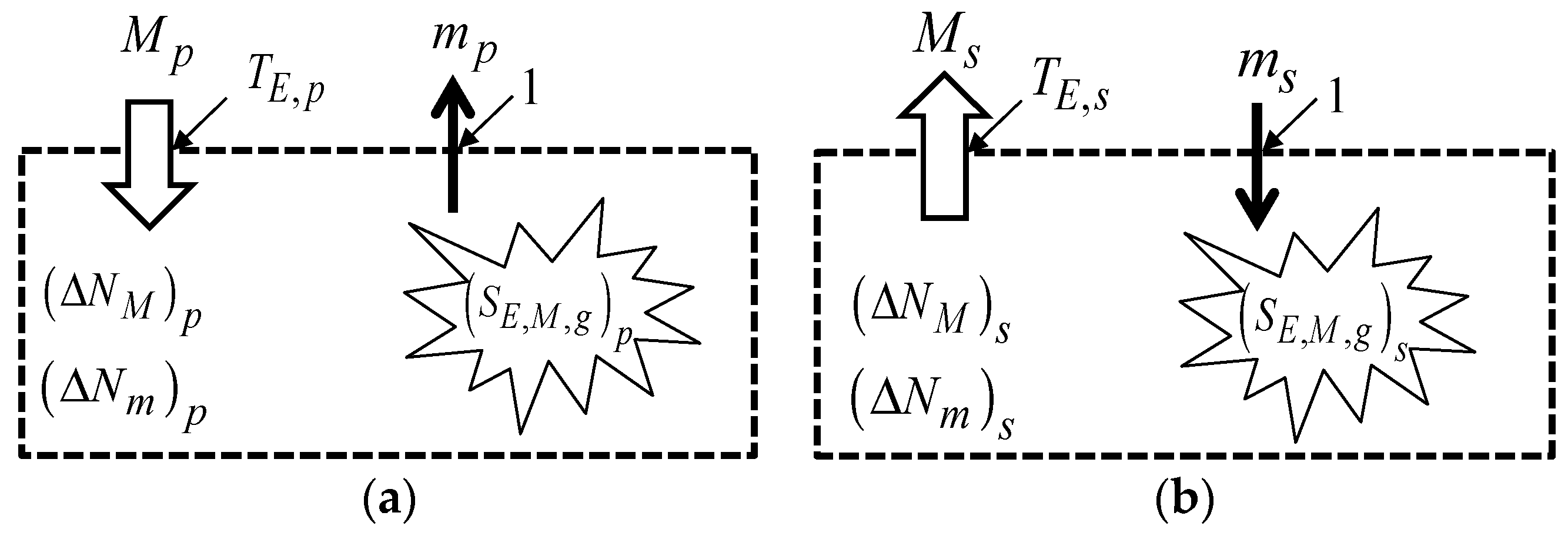

4.1. Purchasing Process

4.2. Selling Process

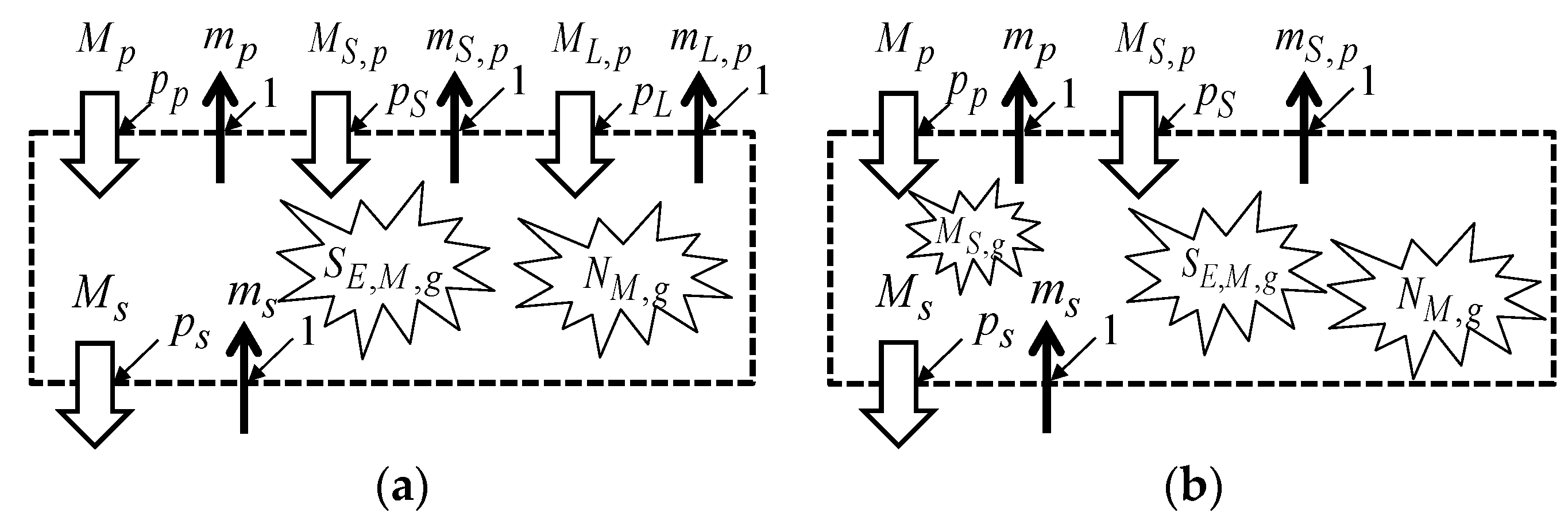

4.3. Trading Process

4.4. Trading with Null Economic Entropy Generation

4.5. Trading Operations Involving Services

4.6. Services as Economic Friction/Viscosity

4.7. Additional Notes on the Generation of New Units and Their Introduction to the Market

5. Merchandise Transfer through an Economic Temperature Difference

5.1. Merchandise Transfer through a Finite Economic Temperature Difference

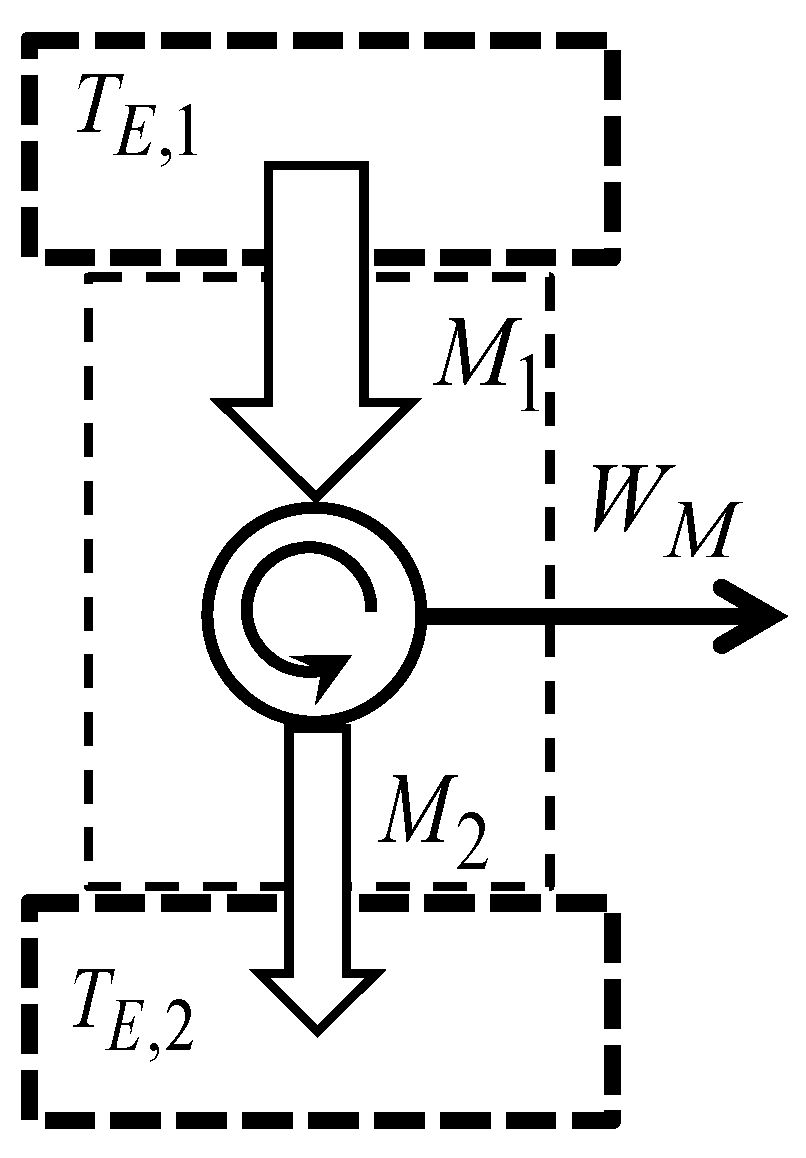

5.2. The Economic Carnot Cycle

5.3. Additional Notes on the Reversible and Irreversible Economic Processes

5.4. How to Proceed toward More Reversible and Perfect Economic Processes?

6. Interpreting Some Observations of Economic Activity

6.1. Thermodynamics and Economics

6.2. Some Observations and Conclusions on Economic Activity

- -

- Economic activity is Second Law-oriented: firstly, thoughts are based on the economic Second Law balance equation and its terms, after which actions are taken based on the economic First Law balance equation and its terms to reach the expected (Second Law balance equation) objectives.

- -

- Individuals are naturally trained to conduct economic Second Law balance equation calculations (are naturally trained to conduct financial value calculations), even through quick mental calculations, but not to naturally conduct (thermodynamic) Second Law balance equation calculations.

- -

- Financial accounting of economic processes is based on the economic entropy (financial value) balance equation.

- -

- Trading generates profit but does not add value, corresponding to economic entropy generation (financial value generation) but not to added intrinsic value (not to intrinsic value generation) (economic entropy generation, but no new merchandise units generation).

- -

- Commercial activity increases the unit prices of merchandise (goods and services) but does not increase the intrinsic value of those goods and services.

- -

- Productive and/or creative processes create value (generation of better or new merchandise units), giving rise to added value products and/or services, introduced into the market at higher unit prices, or to new products and/or services generation introduced into the market at finite unit prices.

- -

- Frequently, some goods are obtained (purchased) as merchandise, at given unit prices, but they are used or stored as merchandise wealth (with no trading motivations), and they can later be treated again as merchandise, given unit prices, and traded. As referred to in Section 2.2, for example, the load of a truck (the truck itself having been obtained previously as merchandise) is merchandise (tradable) but not the truck itself; however, in a different context, the truck can itself be the traded merchandise.

- -

- Acquisition of goods (merchandise) and their use or storage as wealth even if they are not wealth (they were not obtained at, nor have they, null unit prices), and their eventual later sale is expected by both individuals and corporations.

- -

- Everyone, individuals and corporations, likes to store (set aside) some goods as wealth, thus implicitly assuming that they are not on the market (they have null unit prices). However, if placed on the market, given them non-zero unit prices, which is usually referred to as selling the family silver, in the sense that merchandise wealth is converted into tradable merchandise.

- -

- Accumulation of generated economic entropy (generated financial value) is expected by both individuals and corporations.

- -

- Accumulation of (merchandise and monetary) wealth is expected by both individuals and corporations.

- -

- Wealth (merchandise and monetary) is not used to satisfy the common day-by-day needs, corresponding to units set aside (not to be traded, nor exchanged in trading).

- -

- Education, training, and skills and competencies acquisition strongly increase the potential for innovation and the creation of new merchandise units. These are originally generated at null unit prices (originally generated as merchandise wealth), but when introduced into the market (giving them non-zero unit prices), that results in merchandise economic entropy generation, that is, in merchandise financial value generation.

- -

- Technologically developed equipment, machines, and facilities strongly increase the potential for high volume flow rate production of new merchandise units as merchandise wealth, which, once introduced into the market (at higher unit prices), results in increased merchandise economic entropy generation, that is, in increased merchandise financial value generation.

- -

- Services that are originally obtained as new units of merchandise wealth at null unit prices and released/sold at non-zero unit prices, and that cannot be later used as tradable merchandise (that are extinguished after their first release, and thus do not have any reproductive effect), are the economic analogs of the mechanical work dissipation into heat by friction. Consider, for example, the cash operator of a supermarket. The cash operator may use its time and skills to perform cash operations for free and thus generate units of service as merchandise wealth. However, as the cash operator is paid for the service, this corresponds to giving unit prices to the so-generated units of service as merchandise wealth and introducing them into the market, which the supermarket customer is paying for. However, the supermarket customer cannot take advantage of the purchased units of service to sell them later at a higher unit price, nor to reproduce/replicate them. The potential of the units of service of the cash operator ceases in the cash operations. The same applies to the cleaning, security, or maintenance services of the supermarket. This corresponds to converting (dissipating) merchandise wealth into tradable merchandise, similar to what happens in Thermodynamics with mechanical work dissipation into heat, which is lost. It is in this sense that those services that cannot be repeatedly traded at higher and higher unit prices, or that do not have a reproductive effect, such as education and training, are like merchandise wealth dissipation as tradable merchandise that is lost, in the sense that it has no further useful effect.

- -

- Non-reproductive services are the economic friction, corresponding to merchandise wealth dissipation, with no further useful economic effect (in the same way as in the thermodynamic systems friction corresponds to mechanical work dissipation as heat, with no further useful effect).

- -

- Reproductive services have some associated economic irreversibility, but they increase the potential for new merchandise units generation, and thus they have further useful economic effects.

- -

- Economic equilibrium (economic reversibility, economic perfection) means trading with no profit, or with new merchandise units generation retention as merchandise wealth.

- -

- Economic irreversibility corresponds to economic non-equilibrium associated with merchandise economic entropy (merchandise financial value) generation, associated in turn with profit generation in trading operations or the introduction into the market (at non-zero unit prices) of the new merchandise units previously obtained/generated as merchandise wealth.

- -

- When central banks introduce monetary values into the economy, they generate monetary economic entropy, which contributes to a greater departure from the economic equilibrium and increased economic irreversibility.

- -

- Natural resources (air, water, solar energy, wind energy, minerals, forests, fuels, etc.) are economic wealth once they can be primarily obtained at null unit prices. However, once harvested and placed on the market, giving them non-zero unit prices corresponds to converting them into tradable merchandise, with the corresponding merchandise economic entropy generation (merchandise financial value generation).

- -

- Individuals and corporations strive to improve their performances in terms of economic growth, which corresponds to the increase in economic entropy through economic entropy generation (economic irreversibility and economic imperfection); they do not strive to move toward economic reversibility and perfection.

- -

- Market regulation and fair-trading initiatives lead to a less aggressive economy, containing economic entropy generation (containing financial value generation), pulling toward a more perfect and more reversible economy.

- -

- Inflation corresponds to an increase in the unit prices of merchandise (goods and services) which is not accompanied by any change, improvement, or intrinsic added value of those goods and services, corresponding thus to merchandise economic entropy generation (requiring increased numbers of monetary units in the purchasing and selling of those merchandises).

- -

- In the past, central banks had the equivalent of the circulating monetary units in gold, which is no longer the case. The financial markets take the monetary units as merchandise, with no effective merchandise counterpart existence. The monetary financial values involved in the financial markets are thus artificial monetary economic entropy, in the sense that they have no effective (real merchandise) counterparts.

- -

- Donations are (merchandise or monetary) wealth transfer interactions, as they are not motivated by trading, and the donated money is not exchanged as compensation for merchandise trading. Donations have associated null unit prices.

- -

- Taxes paid to the state are monetary wealth transfers, as they are not monetary units exchanged as compensation for merchandise trading. In a way, taxes paid to the state can be seen as forced donations to the state, and the money collected by the state is monetary wealth.

- -

- When the state grants a subsidy for purchasing goods or services, it is as if it was providing the purchase of those goods or services at lower unit prices. The state enters monetary wealth (collected from the taxes paid to it) into the process, which is transferred to the merchandise seller (who is selling the merchandise at a higher unit price (at a lower economic temperature)) as monetary exchange involved in the merchandise purchasing, the merchandise becoming available at a lower unit price (at higher economic temperature). It is as if merchandise were transferred from the lower economic temperature to the higher economic temperature and thus in a direction contrary to that of normal merchandise transfer, using the invested wealth for that purpose. This process is similar to a heat pump, which receives mechanical work (heat and infinite temperature) to promote heat transfer from a lower temperature to a higher temperature, thus in a direction contrary to that of normal heat transfer, using the invested mechanical work for that purpose. Thus, a subsidy from the state acts like a merchandise pump, promoting merchandise transfer from a lower economic temperature (a higher unit price) to a higher economic temperature (a lower unit price), thus economically heating the economy.

- -

- If I grow corn and my neighbor grows beans, and I exchange some of my corn for some of his beans, but without me selling him corn and him selling me beans, there are no unit prices for the corn or beans, there is no merchandise traded, and there is no money involved in the process. Only merchandise wealth is generated and transferred in such a process, and no economic entropy (no financial value) is generated. This is thus a perfect, economically reversible, economic process.

- -

- If I invest some of my time and skills, which I have available free of charge (at null unit prices), to clean my house, I do not need money to pay for house cleaning services. In such a process, I am using generated merchandise (services) wealth (time and skills), which is destroyed in the cleaning operation, and neither merchandise to be traded nor money has been involved in such a process, which does thus not contribute to economic entropy generation. Everything we can do for ourselves, using our time, skills, and resources, does not involve the trade of merchandise or the exchange of money and does not contribute to the generation of economic entropy.

7. Finishing Notes

- -

- Revisiting, reviewing, comparing, adopting, adapting, and perhaps redefining some of the concepts, viewpoints, and insights of Thermodynamics and Economics;

- -

- A different and new perception of Economics and economic activities from the perspective of Thermodynamics, with a significant potential for discovery and knowledge creation in both Economics and Thermodynamics;

- -

- A set of concepts and quantitative tools for economic interpretations and analyses through the lens of Thermodynamics;

- -

- Opening new ways of thinking and analysis, outside the box, in both Economics and Thermodynamics;

- -

- New analyses, observations, interpretations, methodologies, conclusions, bridges, and interrelations in Economics and Thermodynamics, additionally relating and comparing these two fields;

- -

- Conducting more advanced and specific analyses, using the new tools, from which new and important revelations, relations, insights, and interpretations could emerge in both Economics and Thermodynamics;

- -

- Analysis of economic processes and economic systems from new perspectives and using new tools, derived from physical laws;

- -

- Obtaining the best from the cross-fertilization of Thermodynamics and Economics, with mutual benefits and the development of a fertile interface area with immense potential;

- -

- New pedagogical approaches for both Thermodynamics and Economics teaching and learning, with the more easily understandable aspects of one helping to understand the less easily understandable aspects of the other. In addition, new teaching/learning methodologies could emerge from the similarities between Thermodynamics and Economics, even if caution is always needed when teaching/learning through analogies;

- -

- Seeing Thermodynamics and Engineering Thermodynamics as live and relevant disciplines, claiming new and innovative developments, instead of having the commonly misconceived static, stabilized, frozen, dated, and self-contained character;

- -

- The application of the previous point not only in Thermodynamics and Engineering Thermodynamics, but also in Economics and, additionally, in both Economics and Thermodynamics simultaneously, with special emphasis on their interface area;

- -

- Enlarging the capacity of Thermodynamics for the understanding and analysis of numerous phenomena and processes, the proposed similarities giving scope for more new ways of understanding and analysis than before, even in the very different and far- field of Economics.

- -

- A four-Laws structure similar to that of Thermodynamics that can be set for Economics;

- -

- Additional interesting and useful observations to be made concerning the economic Carnot cycle;

- -

- A rigorous and detailed derivation of the economic Second Law that can be similarly conducted, as it is well established for the Second Law of Thermodynamics, leading to the formal definition of the economic temperature and economic entropy;

- -

- Formal developments that can be conducted, leading to the definition of the economic temperature scale;

- -

- Similar structures and developments that can be made to regard Economics through the lens of Thermodynamics, broader than those presented in the present work, which will be the subject of future works.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| E | Energy |

| F | Monetary exchange rate |

| i | ith merchandise species |

| k | kth monetary species |

| m | Number of monetary units |

| M | Merchandise transfer interaction |

| Merchandise transfer flow rate | |

| N | Number of merchandise reservoirs |

| N | Number of units |

| p | Unit price |

| S | Entropy |

| t | Time |

| T | Temperature |

| V | Value (financial value) |

| W | Wealth transfer interaction |

| Wealth transfer flow rate | |

| Subscripts | |

| E | Economic |

| f | Final |

| F | Financial value |

| g | Generation |

| i | Initial |

| i | ith merchandise species |

| in | Inlet |

| j | jth merchandise reservoir |

| k | kth monetary species |

| lost | Lost |

| m | Monetary |

| M | Merchandise |

| out | Outlet |

| p | Purchasing |

| s | Selling |

| t | Trading operation |

| W | Wealth |

References

- Moran, M.J.; Shapiro, H.N.; Boettner, D.D.; Bailey, M.B. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 8th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Çengel, Y.A.; Boles, M.A. Thermodynamics—An Engineering Approach, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, A. Advanced Engineering Thermodynamics, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, P.A.; Nordhaus, W.D. Economics, 19th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.; Wells, R. Economics, 4th ed.; Worth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. Energy and Economic Myths—Institutional and Analytical Economic Essays; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. The Entropy Law and the Economic Process; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. La Décroissance; Entropie, Écologie, Économie; Éditions Sang de la Terre: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, E.L. The three Laws of Thermodynamics and the theory of production. J. Econ. Issues 2004, 38, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S. Nicolas Georgescu-Roegen & la Bioéconomie; Éditions le passager clandestin: Lorient, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burley, P.; Foster, J. (Eds.) Economics and Thermodynamics—New Perspectives on Economic Analysis; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M. Statistical Physics and Economics—Concepts, Tools and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. The Physical Foundations of Economics—An Analytical Thermodynamic Theory; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmel, R. The Second Law of Economics: Energy, Entropy, and the Origins of Wealth; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, R.U.; Nair, I. Thermodynamics and Economics. Phys. Today 1984, 37, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, R.U. Eco-thermodynamics: Economics and the Second Law. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 26, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, J.L. Thermodynamic analogies in economics and finance—Instability of markets. Phys. A 2003, 329, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saslow, W.M. An economic analogy to thermodynamics. Am. J. Phys. 1999, 67, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.V. Thermodynamic laws applied to economic systems. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 2009, 2, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Annila, A.; Salthe, S. Economies evolve by energy dispersal. Entropy 2009, 11, 606–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, H.; Quevedo, M.N. Statistical thermodynamics of economic systems. J. Thermodyn. 2011, 2011, 676495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabes, A. What can economists and energy engineers learn from thermo-dynamics beyond the technical aspects? Real-World Econ. Rev. 2019, 88, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rashkovskiy, S.A. Thermodynamics of markets. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 567, 125699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashkovskiy, S.A. Economic thermodynamics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 582, 126261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddier, F. De la Thermodynamique à l’Économie; Éditions Parole: Artignosc-sur-Verdon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan, A. Entropy Generation Minimization: The Method of Thermodynamic Optimization of Finite-Size Systems and Finite-Time Processes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carnot, S. Réflexions sur la Puissance Motrice du Feu et sur les Machines Propres a Développer cette Puissance; Bachelier: Paris, France, 1824. [Google Scholar]

- Carnot, S. Réflexions sur la Puissance Motrice du Feu et sur les Machines Propres a Développer cette Puissance; Gauthier Villars: Paris, France, 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered; Blond & Briggs: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

| Purchasing | Unit Price Increase | Selling | Trading Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔNM [U] | Mp | 0 | ||

| ΔSE,M [€] | Mp · pp | |||

| ΔNm [U] | 0 | ms | ||

| ΔSE,m [€] | 0 | ms × 1 | ||

| SE,M,g [€] | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, V.A.F. Looking at Economics through the Eyes of Thermodynamics. Energies 2024, 17, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112478

Costa VAF. Looking at Economics through the Eyes of Thermodynamics. Energies. 2024; 17(11):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112478

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Vítor A. F. 2024. "Looking at Economics through the Eyes of Thermodynamics" Energies 17, no. 11: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112478

APA StyleCosta, V. A. F. (2024). Looking at Economics through the Eyes of Thermodynamics. Energies, 17(11), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112478