Abstract

This research explores how participants in an innovation ecosystem, operating without a focal firm, can collaboratively envision and create societal value beyond their individual business goals. Using participatory action research, the investigation focuses on two cases within the offshore wind energy sector, involving four complementary enterprises and nine enterprises that are both complementary and competitive. The findings suggest that ecosystem participants can collectively pursue opportunities for sustainable value creation that surpass the interests and goals of individual firms. This shift towards a future-oriented, ecosystem-wide perspective was driven by the focus on ecosystem-level value propositions and the dynamic organizing of heterogeneous knowledge, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors, enabling successful future-oriented sensemaking. The research process highlights practices that led to significant innovation outcomes, such as halving investments, reducing accidents and rework, accelerating operational flow, and fostering long-term investments, like a floating port for installation and maintenance improvements. This study enhances understanding of how future-oriented sensemaking in innovation ecosystems without a focal firm can drive innovation and societal value creation, offering insights for practitioners, academics, and policymakers on governance and collaborative efforts to enable value creation in innovation ecosystems.

1. Introduction

The critical importance of achieving net-zero CO2 emissions was underscored at the UN Climate Change Conference in November/December 2023 [1]. Transitioning to renewable and clean energy necessitates a multifaceted approach involving various actors and enterprises, each navigating their independent yet interdependent actions. This complex scenario requires diverse entities to collaboratively make sense of future actions within innovation ecosystems to achieve CO2 reduction and reach for affordable energy. Addressing this comprehensive challenge calls for a thorough understanding of future-oriented sensemaking to facilitate effective and efficient collaboration within innovation ecosystems, leading to the following research question:

How can innovation ecosystems pursue future sensemaking to enable innovation for value creation?

The purpose of this research is to contribute to the scholarly understanding and practical approaches that enable future sensemaking within innovation ecosystems, with the objective of increasing value creation in society. This study investigates two cases within the early phases of offshore wind energy innovation ecosystems. The first case involves four complementary enterprises, while the second case includes nine complementary and competing enterprises. This research is conducted using a participatory action research approach, closely engaging with practice to address both practical applications and conceptual insights derived from the activities of the research participants.

The concept of sensemaking, initially introduced by Weick [2], has evolved over time, as highlighted in the comprehensive literature reviews conducted by Maitlis and Christianson [3] and Sandberg and Tsoukas [4]. These literature reviews emphasize aligned tendencies in the sensemaking literature. Especially, Sandberg and Tsoukas emphasized a tendency in the sensemaking literature to focus excessively on the past, which needs to shift towards more dynamic, future-oriented processes to address climate challenges more efficiently and effectively. However, research on interorganizational sensemaking, particularly regarding future-oriented sensemaking, remains limited [5,6]. This means that relevant extant literature regarding the research question remains scarce.

Value creation at the innovation ecosystem level emphasizes collaborative efforts beyond individual and organizational self-interests to exploit and explore various forms of value, such as instrumental, moral, and intrinsic values [7]. The perception of value varies among ecosystem participants [8], leading to governance and coordination challenges and necessitating a cross-disciplinary and multi-layered approach to the literature and practice activities [9].

The empirical context of offshore wind energy innovation ecosystems aims to shed light on future-oriented sensemaking within innovation ecosystems and the potential for CO2 reduction through renewables to pursue the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDG 7) for “affordable and clean energy” [10]. This study examines two cases in the front-end early phases of value creation in innovation ecosystems, one case in the Baltic Sea and one case in the North Sea. The first case involves four complementary ecosystem enterprises, each with two participants in leadership and expert positions. The second case involves nine enterprises, both complementary and competitive, each with two participants in leadership positions.

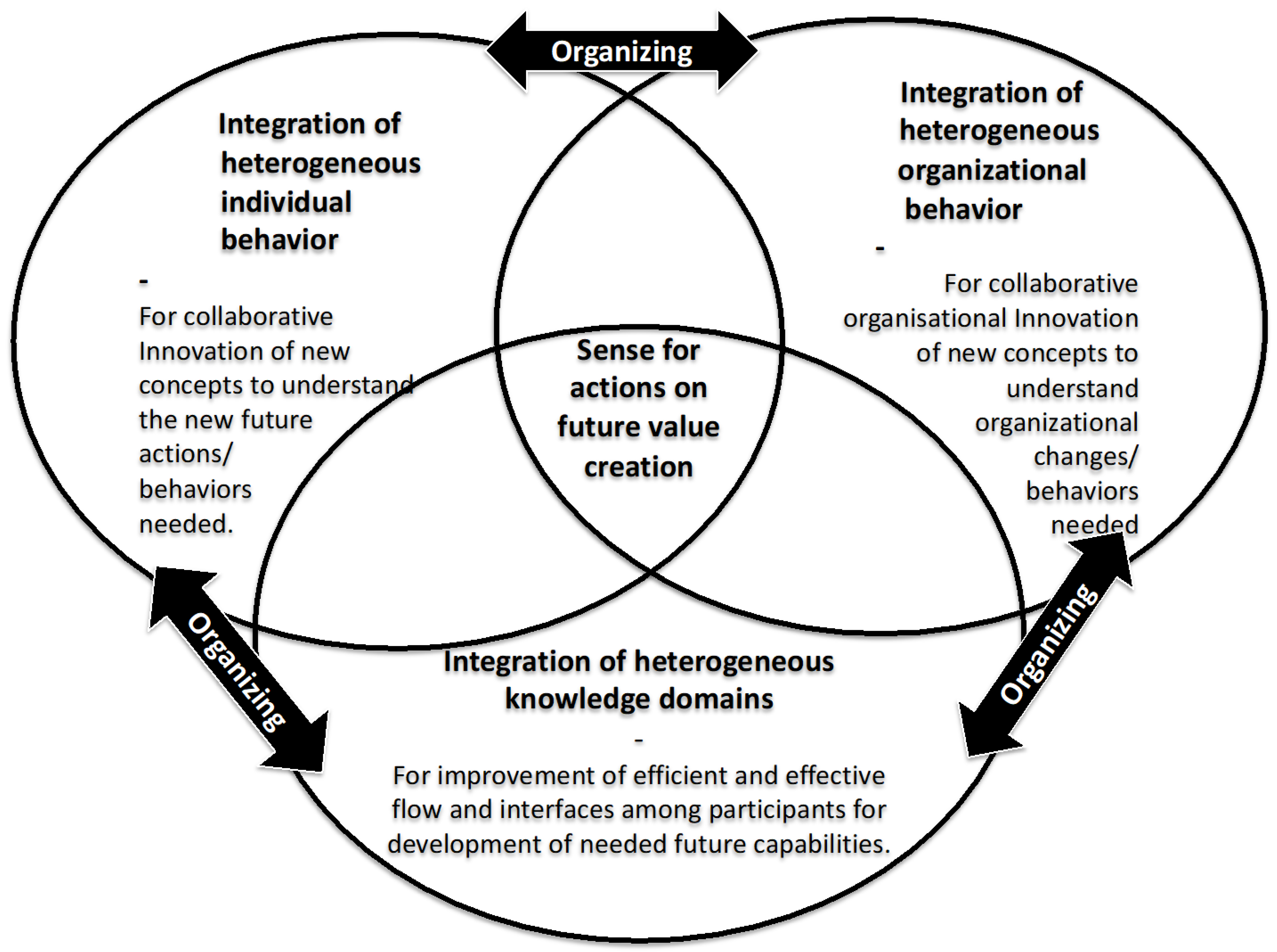

The results of this research highlight the importance of the dynamic organizing and integration of heterogeneous domains, including individual behavior, organizational behavior, and knowledge, to enhance value creation. Furthermore, the research process in the two cases outlines practices to achieve these outcomes. In Case 1, the results were obtained through the development of standards, increased flexibility via both explorative and exploitative innovation, and improvements in hinterland logistics. These efforts successfully halved the investment needed in the port and reduced accidents and rework challenges, thereby making the operational flow through the port faster and more reliable. In Case 2, the results were achieved by developing standards, enhancing flexibility through both explorative and exploitative innovation, and improving port flow. This case identified collective best practices for faster flow through the port and the necessary sharing of facilities for, e.g., the decommissioning of wind turbines and suggested the development of a floating port to improve installation and maintenance. The two cases showed aligned development initiatives with noticeable context-specific and different outcomes.

This introduction presents the research question, its relevance, and the conceptual framework of sensemaking and innovation ecosystems. Additionally, the existing literature is reviewed more thoroughly in the next section on sensemaking and innovation ecosystems. Next, the method illuminates the participatory action research (PAR) approach, case study contexts, data collection, and analysis. Then, the findings are analyzed to state the insights gained from the case studies, highlighting the process of future sensemaking, value creation at the ecosystem level, and the contributions obtained. The discussion addresses the implications in practice and the generalizability of the EcoSense model. The conclusion finalizes the article.

2. Literature Review

The extant literature emphasizes the necessity of a focal firm in innovation ecosystems to create value, as shown in the review by Möller, Nenonen, and Storbacka [11]. However, many independent yet interdependent enterprises collaborate on large infrastructural projects without a focal firm to guide future sensemaking within innovation ecosystems. Therefore, the literature is underdeveloped on the topic of future sensemaking in innovation ecosystems without a focal firm. Furthermore, the high degree of Knightian unknowns [12], where deviations and probabilities of successful implementation are unknown ex ante, highlights the need for research on the front-end pre-phases of innovation at the ecosystem level in uncertain environments [13].

The research question addresses the literature on sensemaking and innovation ecosystems to enable future value creation. These literature streams note the importance of integrating heterogeneous knowledge domains, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors to support innovation and future sensemaking for value creation. These levels within the innovation ecosystem are highlighted as important and necessary by Autio and Thomas [14] and are thus reviewed.

2.1. Sensemaking to Enable Future Innovation for Value Creation

Weick [2] emphasized in his seminal work on sensemaking in organizations that reality is constructed through enactment. He highlights the inherently retrospective approach of enactment with the question: “How can I know what we did until I see what we produced?” [2] (p. 30). This retrospective approach based on past actions creates challenges and tensions when new innovative actions are required to enhance future value creation initiatives among actors. Weick [2] (p. 72) explains the need for a process approach, called “organizing”, to expand and perpetuate past retrospective understandings to produce future innovation for value creation [2,5].

Literature reviews on sensemaking by Maitlis and Christianson [3] and Sandberg and Tsoukas [4] note that the understanding of sensemaking, both in theory and practice, has narrowed over time. The sensemaking literature has focused on deliberate enactment without considering temporality, either from other experiences or by introducing new frameworks for new actions to create value [5,15]. Temporality here is understood as “being-in-the-world” (Dasein), which means the active involvement and contribution of participants in emerging collaborative innovative activities. Additionally, the sensemaking literature has become preoccupied with present issues—also called logocentrism [4,5]—at the expense of what is absent and not yet enacted. Moreover, the sensemaking literature has centered around human ordering practices—also called anthropocentrism [4,5]—in crisis situations, excluding other ordering practices in ordinary situations [5]. Enhanced empirical research on organizing future sensemaking practices is called for [5], as retrospective sensemaking processes are inadequate for ambiguous settings such as those revealed in innovation ecosystem contexts [16].

2.2. Innovation Ecosystems to Enable Future Value Creation

The concept of innovation ecosystems represents a system that includes any organization contributing to offerings for shared value creation [16]. This is a more broad and loosely coupled definition than the previous definition of business ecosystems containing a network community of organizations that co-evolve their capabilities and roles in response to external environmental changes and innovation [17].

Adner [18] advanced the understanding of innovation ecosystems through the concept of the “ecosystem-as-structure”, highlighting “ecosystems as configurations of activity defined by their value proposition”. The configuration of value propositions among independent yet interdependent enterprises focuses on collaborative value creation as the starting point for future sensemaking in innovation ecosystems.

In the literature, Adner [18], Reypens et al. [19], and Möller et al. [11] question the practicality of assuming a single focal firm can span the entire ecosystem efficiently and effectively. It is suggested that ecosystem participants can develop a thorough understanding of their ecosystem’s characteristics and collaboratively pursue value creation at the ecosystem level [18]. Open dialogs are emphasized to organize innovation initiatives, integrating heterogeneous knowledge domains and individual and organizational behaviors to enable collaborative ecosystem innovation for future value creation [6,18,19].

2.3. Integration of Heterogeneous Knowledge Domains

The literature suggests the integration of heterogeneous knowledge domains [20,21] to sustain legitimacy and ownership of practices across domains. Innovation is cross-disciplinary, as noted by Dodgson, Cann, and Phillips [21] in their definition of innovation as the “successful application of new ideas”. Therefore, integrating heterogeneous knowledge domains is necessary to pursue innovation. Recognizing “other knowledge domains” is essential for open dialogs to understand potential value creation across the diverse patchwork of knowledge domains in the innovation ecosystem [18,22].

2.4. Integration of Heterogeneous Individual Behaviors

The literature suggests integrating individual behaviors [19] to harness individual contributions and avoid defiance. An understanding of individual behaviors can be found in psychological attitudes and preferences, as revealed in Jung’s [23] seminal work on personality archetypes, further elaborated by Jacoby [24] and Csikszentmihaly [25,26] for innovation performance. Jung [23] highlighted continuums of individual behavior: introversion versus extroversion (how people react to inner and outer experiences) and thinking versus feeling (how people make decisions). This matrix illustrates four personality types [23,24,25,26,27], respectively: “details and procedures” (introvert thinking), “people and caring” (introvert feeling), “ideas and involvement” (extrovert feeling), and “goals and competition” (extrovert thinking). Creative individuals and teams can integrate these opposing behaviors to pursue innovative value creation. Csikszentmihaly [25,26] supports Jung’s [23] suggestion through his description of “flow”, based on interviews with creative individuals in various fields (athletes, artists, scientists, and ordinary employees).

2.5. Integration of Heterogeneous Organizational Behaviors

The literature suggests integrating organizational behaviors [19] to leverage organizational knowledge and experiences and utilize the diverse objectives of ecosystem enterprises for future actions. Cameron and Quinn [28] highlight the competing organizational behavior framework, which they claim has “high congruence with well-known and well-accepted categorical schemes that organize the way individuals think, their values and assumptions, and the ways they process information” [28], referencing Jung [23]. This framework combines two continuums: internal (inner organizational focus) versus external (outward organizational focus) and stability (reasoning based on thinking) versus flexibility (reasoning based on feelings). This creates four organizational behaviors: “hierarchy-control”, “clan-collaboration”, “adhocracy-development”, and “market-competition” [28]. These behaviors, perceived as competing yet overlapping within the organization, mobilize multiple stakeholder actions across organizational boundaries, as suggested by Reypens et al. [19]. Innovation ecosystems are suggested to represent problematic, open-ended temporality for actors, which cannot be mastered through planning practices alone [22].

2.6. Summary of Gaps in the Literature for Research

Both the sensemaking and ecosystem literature highlight the need for integrating heterogeneous knowledge domains, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors to enable ecosystem future innovation for value creation. However, these concepts have only been scarcely researched empirically, indicating gaps in understanding. Future research should thus, amongst others, address the following sub-questions:

1. Can innovation ecosystem participants make sense of innovation for future value creation at the ecosystem level?

2. Can innovation ecosystem participants collaboratively make sense of innovative actions to enable future value creation?

Research addressing these questions can extend current knowledge and contribute to practice and the literature in the field.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context and Participants

Both cases are situated within offshore wind parks, which consist of wind turbines located at sea. Typically, a variety of stakeholders from different countries participate in offshore wind park ecosystems, engaging in construction, production, assembly, installation, commissioning, operation, and maintenance (O&M) for the production of MWh and subsequent use of energy by end users. Nearby ports play a crucial role in supporting offshore wind parks. They serve as transport corridors, providing spaces for renewable wind activities [29].

The success of offshore wind energy parks is measured by the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCoE). All energy sources, such as oil, coal, and onshore wind, are compared using this measure to assess their ability to provide “affordable and clean energy” in SDG 7 [10]. The LCoE is defined as the sum of discounted lifetime generated costs (EUR) divided by the sum of lifetime electricity output [30]. Reducing the LCoE is essential for providing affordable energy and benefiting both climate and society. The LCoE can be reduced by increasing the production of MWh from the wind park and/or by reducing costs. Many independent yet interdependent actors contribute to reducing the LCoE through various activities within the innovation ecosystem [29].

Ports function as transport corridors, accommodating components and equipment arriving by land or sea from other production facilities or ports, ranging from nearby to distant locations. All actors within the offshore wind park energy innovation ecosystems utilize nearby ports for logistics, production, mounting, operations, maintenance, and decommissioning activities. These ports also interact with other ecosystems, such as transport and fisheries. Consequently, multiple stakeholders are intertwined within and across innovation ecosystems. Data collection for the two cases was conducted from September 2017 to June 2018 and from September 2019 to January 2022.

3.2. Research Design

The literature highlights the suitability of “action research” for developing theories closely linked to practice and management processes. Given the limited existing literature on innovation ecosystems without a focal firm, it is essential to gain a thorough understanding of emerging phenomena during research. Therefore, the Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach was employed in both cases [31]. This study uses PAR to involve research participants in developing knowledge and understanding, focusing on collaborative phenomena for value creation.

PAR, as described by Creswell and Poth [31], uses recursive dialectical dialogs to capture discussions and actions among participants. It aims to give voice to research participants in data collection and analysis [32,33], allowing comprehensive insights and understanding to emerge. In PAR, research participants are considered knowledgeable agents, while researchers act as facilitators, enabling the collaborative development of new knowledge [32]. The research process was designed in collaboration with participating managers and organizations, with the aim formulated by the managerial participants themselves. The existing literature on open innovation to improve performance and cross-disciplinary innovation [9] was shared with managers, and reflective recursive dialectical dialogs were introduced to unlock discussions and enable innovation for value creation [31].

When managers seemed to get stuck in the same arguments, researchers intervened and introduced reflective recursive dialectical dialogs in PAR, grounded in the Weick and Quinn [34] notion of a “reversed Lewin”. This process involves reversing Lewin’s [35] seminal “unfreeze-rebalance-freeze” model to “freeze-rebalance-unfreeze”. This reversion aims to make participants aware of their own “frozen” assumptions, encouraging open discussions on needed changes of existing frames and developing new discussions to enable innovation and value creation. Otherwise, researchers followed the research process and provided practical support. The PAR approach means that issues not considered actionable by participants do not receive attention [31], allowing participants to develop actionable approaches during the research.

In both cases, research began with individual meetings with participating enterprises to elucidate participants’ perspectives on opportunities for developing the value proposition at the ecosystem level. Two managers or experts from each enterprise attended these meetings. The Business Model Innovation (BMI) approach [36] was used to understand the ecosystem-level value proposition and required activities, resources, customers, and partners. Additionally, the self-reporting online insights tool [37,38] was employed to reveal individual behavior in line with Jung’s [23] seminal theory, and the organizational behavior model by Cameron and Quinn [28] was used by participants to self-report organizational behavior. Subsequently, enterprises proposed action plans for value creation at the ecosystem level. This data collection approach aimed to unveil the intertwined multiple layers, encompassing technical, economic, organizational, and behavioral facets [39,40]. The research then diverged in the two cases, which are explained individually.

3.3. Case 1: Innovation for Future Value Creation in the Baltic Sea

In the first case, four enterprises representing complementary activities aimed at enhancing value creation in the front-end pre-phases of a port development adjacent to a new offshore wind park in the Baltic Sea. The participants included the port itself, the wind park owner, a sea logistics partner, and a land logistics partner. A snowball approach was used to self-select participants, with the port serving as the initial point of contact. These participants were not previously acquainted.

Three collaborative Participatory Action Research (PAR) meetings were held, each spanning one day. Each enterprise was represented by two managers or experts. Future collaborative sensemaking for innovation to create value was conducted according to each participant’s behavior and the behavior of the participating organizations, as shown in Table 1. Because the participants were self-selected in the research it could not be known beforehand how the behaviors would be distributed. The research participants defined their own organizational behavior based on their understanding of individual behaviors obtained during research.

Table 1.

Overview of individual and organizational behaviors—Case 1.

Table 1 delineates the diverse and complementary individual and organizational behaviors in the participating enterprises. The dominant preferred behavior is reported for simplicity, but individual participants may exhibit one or two other preferred behaviors to a lesser extent. The table emphasizes the dynamic nature of collaboration due to the different stands and preferred behaviors of the managerial participants, driving ongoing discussions on various levels. However, participants focused primarily on goals and competitive actions, framed by market and competitive organizational behaviors. This short-term competitive orientation can potentially limit long-term innovation initiatives due to detailed procedures and hierarchical processes, which can challenge explorative innovation [24]. However, all individual behaviors were present in the research and could therefore be used.

The first collaborative PAR workshop resulted in a unanimous decision to further explore port activities through a physical simulation model featuring 3D-printed wind turbine components, vessels, cranes, and other relevant elements within the port. This simulation was conducted during the second PAR workshop. During the third workshop, participants engaged in in-depth discussions regarding proposed enhancements on robustness. The focus then shifted towards required port investments. The developed result on the value creation concept was discussed with a wind turbine producer for reflective feedback and additional suggestions for value creation.

3.4. Case 2: Innovation for Value Creation in the North Sea

In the second case, nine enterprises, characterized by both complementary and competitive activities within the offshore wind energy innovation ecosystem, participated in the early phases of leveraging port spaces in the North Sea. The participants included offshore wind park owners/developers, wind turbine OEMs, logistics and technical enterprises, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with one chosen representative for the SMEs in the hinterland of the port. The participants were again self-selected through a snowball approach with the port serving as the initial point of contact.

The research participants themselves addressed the issue of competition as they recognized the need to strike a balance between protecting their own firm’s core sources of profit and enabling complementors and competitors to profit and protect their proprietary knowledge. The literature acknowledges that this balance can limit competitor collaboration [11]. Additionally, the research participants discussed the benefits of collaboration for innovation and value creation at the ecosystem level. They agreed that non-core knowledge and experiences could be shared and integrated into collaboration for innovation, as long as it did not compromise the protection of their core sources of profit.

All participants in the research possessed core knowledge and experiences. Throughout the research process, the participants disclosed varying levels of knowledge, but they acknowledged the intangible boundary of communication due to their own interests in protecting their firm’s core sources of profit. This awareness allowed for collaboration among participants as they exchanged and integrated cross-disciplinary technical, logistic, maritime, and commercial knowledge for the development of concepts and proposals at the ecosystem level.

Again, future collaborative sensemaking for innovation to create value was conducted according to each participant’s behavior and the behavior of the participating organizations, as shown in Table 2. Again, the participants were self-selected in the research and therefore it could not be known beforehand how the behaviors would be distributed among research participants. Again, the research participants defined their own organizational behavior based on their understanding of individual behaviors obtained during research.

Table 2.

Overview of individual and organizational behaviors—Case 2.

Table 2 presents an overview of the distribution of preferred individual behaviors and organizational behaviors. The dominant preferred behavior is reported for simplicity, but individual participants may exhibit one or two other preferred behaviors to a lesser extent. The table emphasizes the dynamic nature of collaboration due to the different stands and preferred behaviors of the managerial participants, driving ongoing discussions on various levels. It is notable that there was a lack of introverted feeling for behavioral action to support “people and caring”. This may challenge collaboration for innovation to create value, as highlighted in the literature review emphasizing the importance of affectively charged feelings such as inspiration, empathy, and altruism for value creation success [25]. Additionally, the organizational culture was primarily focused on market/competition rather than clan for human development, hierarchy/control, and adhocracy/innovativeness. This market and competition focus may divert attention from the innovation ecosystem level towards individual enterprise self-interest in competitive goal achievement.

In collaboration with research participants and researchers, presentations on BMI, individual and organizational behaviors, and proposed ecosystem-level actions were prepared and delivered by a manager from each participating enterprise during the first ecosystem workshop in January 2020. These presentations fostered open communication based on the distinct perspectives of each enterprise. This comprehensive understanding at the ecosystem level facilitated subsequent PAR discussions during the first and ensuing ecosystem workshops, extending until August 2020. Follow-up telephone interviews were conducted in January 2022 to further enrich data collection.

During the first ecosystem workshop, participants proposed several collaborative BMI ideas to enhance value creation at the ecosystem level. The research proceeded by collectively selecting proposals titled “floating ports”, “decommissioning”, and “best practices” to continue collaborative BMI endeavors aimed at future value creation at the ecosystem level.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted consistently in both cases. All research meetings and workshops were recorded and transcribed, employing an iterative approach to data reflection that contributed to the PAR process. During the research, it became evident that the typical short-term coding techniques used in qualitative research [32], which focus on first- and second-order rubrics, were insufficient for capturing the depth of underlying constructs. This method led to a loss of meaning, as the short coding could not adequately discern and reproduce the nuances emphasized by participants. This challenge has also been encountered in other research contexts [32,40].

To address this issue, an adapted approach was employed, emphasizing longer citations that more accurately represented the participants’ intended meanings. The research material underwent thorough analysis, with selected citations categorized according to the research question and gaps identified in the literature review. This sorting process was applied to both first- and second-order citations.

Ultimately, these analyses were synthesized into a conceptual logic for developing future sensemaking in innovation ecosystems without a focal firm. This approach allowed for a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the data, facilitating the identification of key insights and contributions to the field

4. Results

The analyses originate from the sensemaking of value creation at the ecosystem level as perceived by the individual participating organizations. This sheds light on the ability of research participants to understand value creation at the ecosystem level and collaboratively envision and make future sense of actions to enable and enhance innovation for societal value.

4.1. Value Creation in Innovation Ecosystems

The value creation insights of all research participants were revealed through a focus on the value proposition at the ecosystem level in offshore wind parks. Surprisingly, all participants in both cases easily related to value contribution at the ecosystem level based on retrospective actions within their organizations. A key issue stressed by all participants was the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCoE), a strategic measure for sustaining business opportunities in offshore wind energy ecosystems compared to other energy sources. However, the LCoE spans the lifetime of the offshore wind park, approximately 15–20 years, and individual enterprises have only a limited overview of this period. Despite this limitation, the participants were able to understand the need to focus on the LCoE, as evidenced by quotations from Case 1:

- -

- N4: “We know that subsidies do not provide a sustainable wind business for us. If we have subsidies, we are too dependent on political support, which can often change”.

- -

- N2: “We need to build offshore wind parks on par with other energy sources to support sustainability in society and increase the number of investors willing to fund these projects”.

- -

- N3: “It is necessary for us to reach the next level in the renewable energy revolution and be able to build projects at market prices”.

- -

- N1: “Investments require quite large sums. It is important to get input from users so we can do things right from the beginning”.

These quotations highlight the participants’ understanding of the competition with other energy sources on the LCoE. Overlapping suggestions for value creation at the ecosystem level were revealed in both cases. The finding in Case 1 is summarized as follows:

- Improved sustainability (SDG 7: affordable and clean energy, SDG 17: partnerships for the goals) for reducing the LCoE, with a focus on the following:

- ○

- Development of standards;

- ○

- Development of flexibility—explorative and exploitative innovation;

- ○

- Development of hinterland logistics.

A similar approach was found in Case 2:

- Improved sustainability (SDG 7: affordable and clean energy, SDG 17: partnerships for the goals) for reducing the LCoE, with a focus on the following:

- ○

- Development of standards;

- ○

- Development of flexibility—explorative and exploitative innovation;

- ○

- Improved flow through the port.

Collaborative innovation for value creation at the ecosystem level, beyond individual enterprise interests, can be relatively easily identified. The overall issues identified in both cases indicate a collaborative innovation logic, providing robustness for value creation at the ecosystem level. However, specific operational initiatives differ due to the distinct contexts of each case. At a strategic level, a coherent direction for collaborative future sensemaking and innovation leadership is suggested.

4.2. Collaborative Future Sensemaking to Enable Innovation for Future Value Creation

All workshops conducted in the two cases provided lively debates among research participants, generating rich data for understanding sensemaking for future collaborative innovation and value creation at the ecosystem level.

In the first collaborative workshop in both cases, participants presented their perspectives on value creation at the ecosystem level, anonymous individual behaviors of two participants from each enterprise, organizational behaviors within the enterprise, and suggestions for ecosystem-level activities to create value. After each presentation, numerous questions were posed by other participants, primarily on detailed knowledge domain understandings, such as technical and logistic product and service activities. Once these clarifications were exhausted, the focus shifted to ecosystem goals, discussing their impact on people and organizations, and exploring new ideas to solve challenges and enhance value creation. This process involved participants questioning and answering according to their individual behaviors, enhancing both their own and others’ understandings.

Questions related to organizational behavior included the following: “Who makes decisions in your organization?” “Have you collected detailed information for all employees to use?” “How do you collaborate on innovative activities?” “What is your strategy?” “How far are you in implementing future aims?” These questions provided insights into how participating organizations could collaborate to make future sense of value creation. Participants also criticized their own organizations for hindering value creation through rigidity, lack of collaboration awareness, short-term goals, and excessive competitiveness, offering a mirror to understand these hindrances.

Examples of these elaborations include the following:

- -

- An extrovert-feeling person suggested long-term radical innovations, such as developing a hub-port or floating port, initially rejected by others as unrealistic but later explored in further detail.

- -

- An extrovert-thinking person posed a goal-oriented question, sparking discussions on handling simultaneous wind projects in the port, exploring the idea’s impact on people and organizations, and prioritizing ecosystem value creation.

This collaboration at the ecosystem level, integrating heterogeneous knowledge domains, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors, fleshed out essential concepts and activities, prioritizing innovation for future value creation. It transcended time perspectives from past to future innovative actions, driven by the diverse knowledge and behaviors present in the meetings.

Participants framed the impact of this collaborative future sensemaking as follows:

- -

- NX: “For us, it has been an eye-opener. If you look at the whole process, it will work well for many ports”.

- -

- NY: “Everything is set free, allowing us to model scenarios freely and find the right solutions, balancing advantages and disadvantages”.

- -

- NZ: “A process this open will bring optimization, benefiting end users with a comprehensive layout and solution”.

- -

- NW: “We’ve considered all opportunities, drawing on participants’ experience, leading to good results”.

Participants emphasized the need for integrating knowledge domains, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors for collaborative future sensemaking to address uncertainties in ecosystem concepts and activities for value creation. A key challenge is the potential short-term revenue loss from new product and service concepts due to streamlined activities. However, long-term revenue can increase through enhanced competitiveness of offshore wind park innovation ecosystems. One participant framed this as follows: “The market is large enough for all of us when offshore wind energy can compete with other sources”. Another participant highlighted the importance of preliminary discussions: “Before you start the excel spreadsheet, it’s worthwhile to stand around and discuss and toy with some blocks”.

The results obtained in this research highlight the importance of future sensemaking in innovation ecosystems. The research in the two cases both outlines practices and suggests a concept to achieve value creation in innovation ecosystems. In Case 1, the results revealed a need to develop standards, increased flexibility via both explorative and exploitative innovation, and improvements in hinterland logistics. These efforts successfully halved the investment in the port and reduced accidents and rework to make the flow through the port faster and more reliable. In Case 2, the results revealed the need to develop standards, enhance flexibility through both explorative and exploitative innovation, and improve port flow. These efforts enhanced several best practices and highlighted the sharing of facilities for the decommissioning of wind turbines as very important and suggested the development of a floating port to enable further innovation and value creation.

The EcoSense model in Figure 1 suggests the free-floating integration of the three heterogeneous dimensions for future value creation sensemaking. One participant summarized the model’s potential: “This is interesting for us, and it will be even more interesting when we can use the insight in specific projects”. These insights are expected to be applied in subsequent interorganizational activities in offshore wind park ecosystems, extending and disseminating innovation in energy ecosystems, thus contributing to the research question on innovation ecosystems creating value at the ecosystem level.

Figure 1.

Organizing to transcend the past for future sense of innovation for value creation—EcoSense model.

The insights gained from Figure 1 contribute the innovation energy ecosystem practitioners understanding the necessary activities to succeed long term in offshore wind energy ecosystems as described in the Section 3 in this research. Additionally, academic understanding is improved for further research to enhance the contributions and dissemination of insights. Furthermore, governmental bodies can use the insights to create enhanced space for involvement among participants to focus on future sensemaking to succeed in value creation in society.

5. Discussion

The participants in this research, representing a segment of the broader innovation ecosystem, primarily contribute insights into the front-end sensemaking processes. While these insights are limited in scope, they hold potential for broader applicability. It is highlighted in the research that front-end processes illuminate how teams create user interfaces that are intuitive, functional, and tailored to user needs, through continuous understanding and adaptation based on user needs and behavior.

As indicated by the participants, the concepts and strategies developed for future sensemaking can be adapted and applied to other ports (N1) and future initiatives (N2). This adaptability suggests that while the findings are confined to the front-end pre-phases of innovation, they offer valuable knowledge for dissemination, aligning with the views of Adner [33]. The effectiveness of this dissemination hinges on the participants’ willingness to share and act upon these new insights.

In terms of organizing, the diverse sensemaking processes proposed in this study facilitate collaborative value creation. This is achieved by enhancing the reliability of “interfaces” and streamlining the “flow” through the port, thus reducing required investments. Such a decentralized approach to innovation and value creation [5,41,42] could lead to considerable cost-effective and efficient MWh production in offshore wind park ecosystems. This approach leverages diverse behaviors across and within organizations, encouraging both exploration and exploitation, as conceptualized by March [43]. March [44] later acknowledged the need for a balance between these two activities, recognizing their complementary nature in fostering organizational ambidexterity. Further research in the diverse ecosystem context has the potential to enhance understanding.

The findings illustrate how sensemaking in ecosystems can address the tension between retrospective and future-oriented activities [2], a concept rooted in the work of Weick [2] and Introna [5]. Further empirical research in varied ecosystem contexts is necessary to understand the generalizability of these front-end pre-phase organizing strategies for balancing exploration and exploitation to boost innovation and value creation in innovation ecosystems.

The EcoSense model proposed from the findings underscores the importance of a long-term perspective for collaborative innovation in ecosystems, potentially conflicting with the short-term revenue goals of participating enterprises. This tension was evident in the concerns raised by research participants. Thus, additional research is needed to understand the long-term impacts of the EcoSense model on the offshore wind park ecosystem, considering both immediate and extended implications. Moreover, this approach likely requires political backing to establish legislative frameworks and funding mechanisms to create an enhanced space for the involvement of participants for future sensemaking activities to enable future innovation to create societal value.

This research contributes to the literature by providing case examples that illustrate how individual enterprises can focus on ecosystem-level value creation, moving beyond their immediate self-interests. This shift in perspective paves the way for managing innovation ecosystems differently from traditional enterprise management, emphasizing diverse aims and a long-term strategy for societal value creation and competitive advantage of enterprises to go hand in hand. This is also found in previous research in micro and small-sized enterprises [45]; however, it is scarcely researched among larger enterprises and in ecosystems. Further research is needed to understand the implications of this shift more thoroughly.

While the offshore wind park ecosystem operates with a clear long-term success metric (LCoE), applicable across various energy innovation ecosystems, other ecosystems might have more varied and ambiguous objectives [46,47]. This diversity could limit the broader applicability of the findings, indicating the need for future research in different ecosystem contexts.

Furthermore, research extending beyond the front-end pre-phase of ecosystem innovation is recommended to enrich our understanding and facilitate wider dissemination. The insights gained from this research should also be examined through mixed methods of qualitative and quantitative research to enhance the understanding of their general applicability and relevance for value creation in society.

6. Conclusions

This research sheds light on how innovation ecosystems can pursue future sensemaking to enable innovation for value creation. The two qualitative participatory action research (PAR) cases were situated within ports connected to offshore wind energy innovation ecosystems. The first case involved complementary ecosystem participants, while the second case included both complementary and competitive participants. These cases were conducted from September 2017 to June 2018 and from September 2019 to January 2022, respectively.

The findings highlight that participants found it relatively easy to identify sensemaking activities at the ecosystem level through their own enterprise lenses. Subsequently, the research participants facilitated future sensemaking through the collaborative integration of heterogeneous knowledge domains, individual behaviors, and organizational behaviors. This collaborative effort aimed to create future value at the ecosystem level. The elaborations transcended past retrospectivity, developing future-oriented sensemaking to enable innovation for value creation, as illustrated in the EcoSense model. Contributions are thus made to ecosystem participants in practice, to academia for further research and dissemination, and to governmental bodies to provide an enhanced space and governance for involvement among participants to focus on future sensemaking to succeed in value creation in society from the start of innovation energy ecosystems to the end.

Funding

The research received external fund from the Danish innovation networks Brandbase and Energy Innovation Cluster for data collection. No grant number is available. Neither of these networks were further involved in the research. A waiver was obtained from energies for the APC.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank first and foremost the participating enterprises contributing anonymous to this article, the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science and respectively the Innovation Network BrandBase and Energy innovation Cluster for financing the data collection. Additionally, the author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers providing valuable input for the article. Last but not least, the author would like to thank research colleagues contributing to the data collection and discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- COP 28. Media Factsheet. 2023. Available online: https://prod-cd-cdn.azureedge.net/-/media/Project/COP28/PRs/PDF-Files/COP28-OG-Charter-Media-Fact-Sheet-21223.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage Publication Series: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Maitlis, S.; Christianson, M. Sensemaking in organizations: Taking Stock and moving forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 57–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Tsoukas, H. Making sense of the sensemaking perspective: Its constituents, limitations, and opportunities for further development. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, S6–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, L.D. On the making of sense in the sensemaking: Decentered sensemaking in the meshwork life. Organ. Stud. 2019, 40, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattringer, R.; Damm, F.; Kranewitter, P.; Wiener, M. Prospective collaborative sensemaking for identifying the potential impact of emerging technologies. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.R.; Skyttemoen, T.; Vaagaasar, A.L. Project Management a Value Creation Approach; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3 (accessed on 6 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Visscher, K.; Hahn, K.; Konrad, K. Innovation ecosystem strategies of industrial firms: A multilayered approach to alignment and strategic positioning. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Strategic Development Goals (SDGs). 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Möller, K.; Nenonen, S.; Storbacka, K. Networks, Ecosystems, fields, market systems? Making sense of the business environment. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 90, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit; Hart, Schaffner, and Marx Prize Essays, No. 31; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1921; Available online: http://www.econlib.org/library/Knight/knRUP.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Bruskin, S.; Mikkelsen, E.N. Anticipating the end: Exploring future-oriented sensemaking of change through metaphors. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Thomas, L.D.W. Innovation Ecosystems—Implications for innovation management. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; Dodgson, M., Cann, D.M., Philips, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 204–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gephart, R.; Totpal, C.; Zhang, Z. Future-oriented sensemaking: Temporalities and institutional legitimation– Oxford scholarship. In Process, Sensemaking, and Organizing; Hernes, T., Maitlis, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 275–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Orlikowski, W.J. Temporal work in strategy making. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 965–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. The Death of Competition: Leadership and Strategy in the Age of Business Ecosystems; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reypens, C.; Lievens, A.; Blazevic, V. Hybrid orchestration in multi-stakeholder innovation networks: Practices of mobilizing multiple diverse stakeholders across organizational boundaries. Organ. Stud. 2020, 42, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J. Stakeholder relationships and social welfare: A behavioral theory of contributions to joint value creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D.M.; Philips, N. Perspectives on innovation Management. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation; Dodgson, M., Gann, D.M., Philips, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M.; Krämer, H.; Koch, J.; Reckwitz, A. Future and Organizations Studies: On the rediscovery of a problematic temporal category in organizations. Organ. Stud. 2020, 41, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.G. Psychological Types; Routledge: London, UK, 1923; Available online: https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Jung/types.htm (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Jacobi, J. The Psychology of C.G. Jung; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihaly, M. Creativity—Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihaly, M. Flow. The Classic Work on How to Achieve Happiness; Rider: London, UK; Sydney, Australia; Auckland, New Zealand; Johannesburg, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J.S.; Melwani, S.; Goncalo, A. The Bias Against Creativity: Why People Desire but Reject Creative Ideas. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture—Based on the Competing Values Framework; Jossey-Bass—A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, T.; Madsen, S.O.; Lutz, S. Perspectives on how Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Innovations Contribute to the Reduction of Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) in Offshore Wind Parks. Danish Wind Industry Association. 2015. Available online: http://ipaper.ipapercms.dk/Windpower/OWDrapport (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Crown Estate. Offshore Wind Cost Reduction Pathways Study. 2012. Available online: https://bvgassociates.com/publications/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on Gioia Methodologi. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/1094428112452151 (accessed on 6 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications. Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Quinn, R.E. Organizational change and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, K. Resolving Social Conflicts; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.L.; Afuah, A. A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, S.; Schurink, C.; Desson, S. An Overview of the Development, Validity and Reliability of the English Version 3.0 of the Insights Discovery Evaluator; University of Westminster. 2008. Available online: https://www.insights.com/what-we-do/validity/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Lothian, A.; Lothian, A. Insights. 1993. Available online: https://insights.easysignup.com (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Jung, C.G. Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious. In The Collected Works of Jung, 2nd ed.; Read, H., Fordham, M., Adler, G., McGuire, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; Volume 9, Part 1; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E.; Sonenshein, S. Grand Challenges and inductive Methods: Rigor without rigor mortis. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E. Orchestrating ecosystems: A multi-layered framework. Organ. Manag. 2021, 24, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, T. Organizing to enable innovation. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2016, 10, 402–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organisational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Explorations in Organizations; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, T. Future Innovation Unleashed for Sustainability in Longitudinal Research in Micro- and Small-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. How companies become platform leaders. In MIT Sloan Management Review. Sloan Select Collection, Ed.; 2015. Available online: http://marketing.mitsmr.com/PDF/STR0715-Top-10-Strategy.pdf#page=70 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Schneckenberg, D.; Velamuri, V.; Comberg, C. The Design Logic of New Business Models: Unveiling Cognitive Foundations of Managerial Reasoning. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).