Method for Spatiotemporal Solar Power Profile Estimation for a Proposed U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid under Hurricanes †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Hurricane Shading on PV Power

1.2.2. Super Grids

1.3. Research Gaps and Motivation

1.4. Challenges

1.5. Contribution

1.6. Paper Organization

2. Materials and Methods

- Model of global irradiance on the tilted PV module [23], formulated in Appendix A.

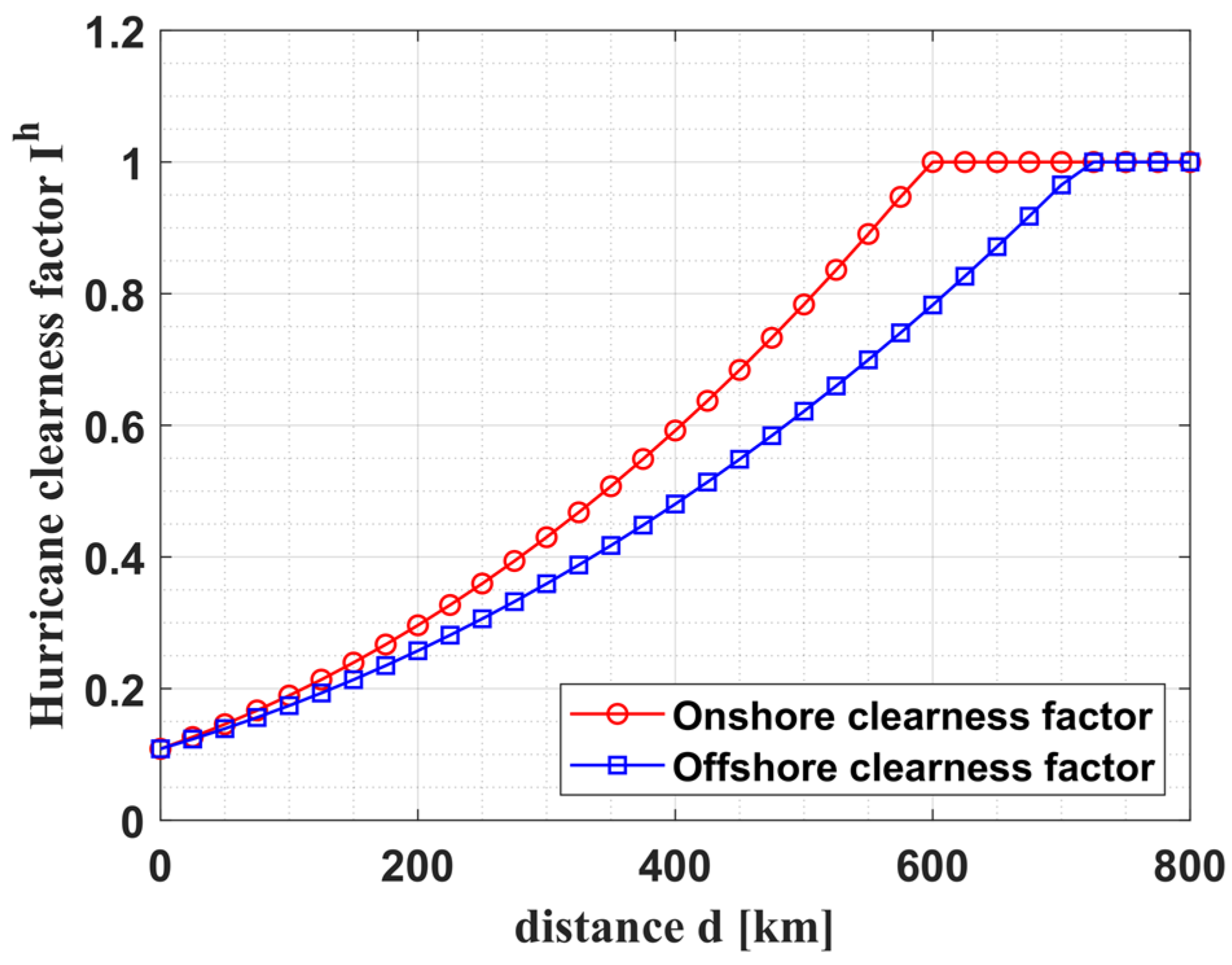

- Model of irradiance decay by the hurricane shading effect [3].

- Conversion of irradiance on a PV module into a power profile, as formulated in [24].

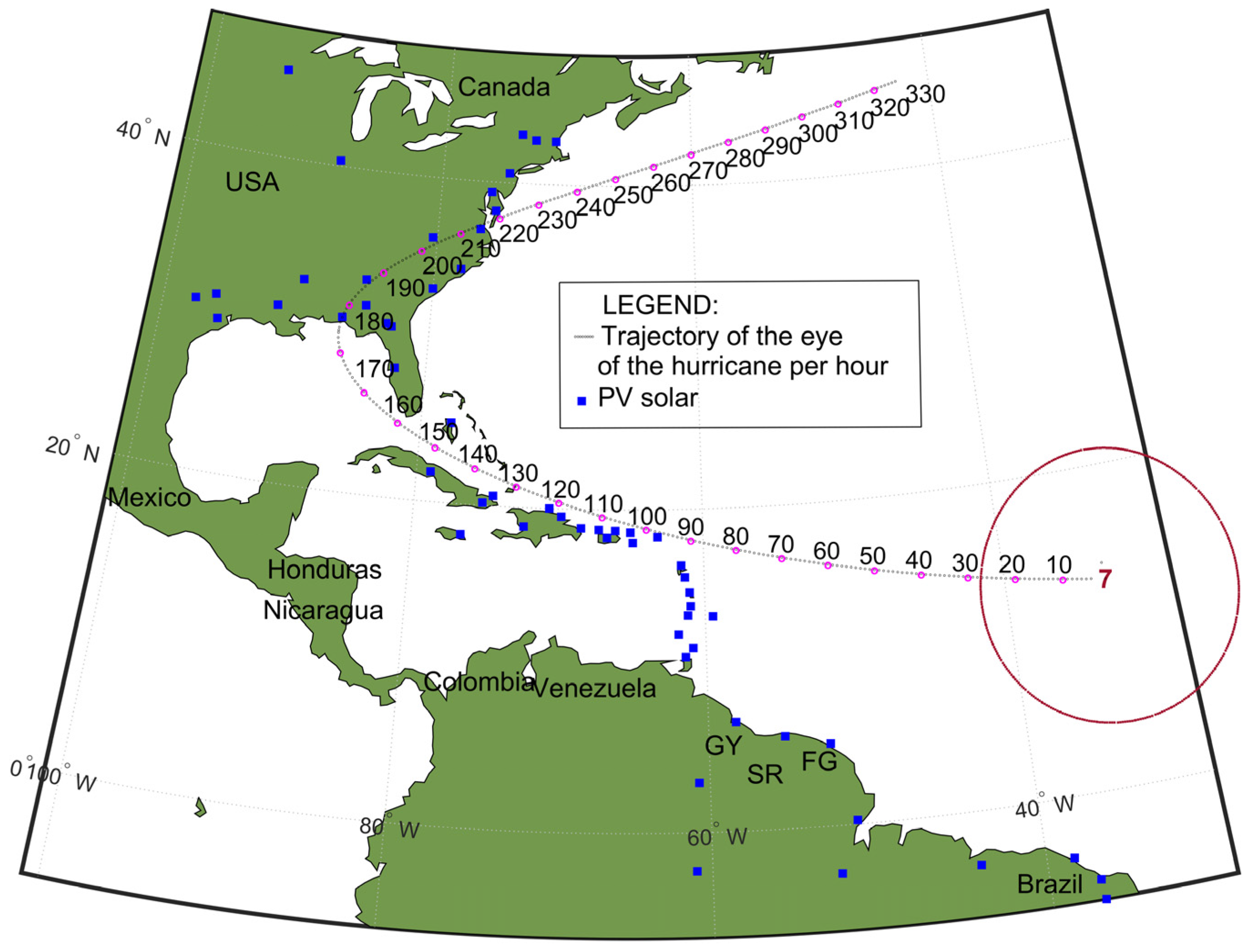

- Model of the hurricane movement over a synthetic parabolic trajectory.

- Model of future PV solar capacity expansion along the U.S.–Caribbean–South America super grid.

- Spatiotemporal estimation of PV solar power profile of super grids under hurricane shading.

2.1. Model of Global Irradiance on the Tilted PV Module

2.2. Model of the Hurricane Shading Effect

2.3. Conversion of Solar Energy into Alternating Current Electric Power

2.4. Model of the Hurricane Movement over a Synthetic Parabolic Trajectory

2.5. Model of Future PV Solar Capacity Expansion in the U.S., Caribbean, and South America

| Countries or Territories | Population | Total Capacity [MW] | Fossil Dep. ) | 2050 Cumulative PV [MWac] | PV Latitude, and Longitude [°] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 339,665,118 | 1,143,266 (est. 2020) | 59.9% | 1,000,000 | Appendix B | [30,31] |

| The Bahamas | 358,508 | 578 | 99.8% | 288 | 24.698981, −77.789604 | [30] |

| Cuba | 10,985,974 | 7479 | 95.5% | 3571 | 21.598426, −78.974099; 19.907734, −75.218468; 20.358009, −74.504742 | [30] |

| Haiti | 11,470,261 | 3453 | 85.8% | 1481 | 18.576618, −72.296021 | [30] |

| Jamaica | 2,820,982 | 1216 | 87.5% | 532 | 17.876148, −76.582014 | [30] |

| Dominican Republic | 10,790,744 | 5674 | 93.4% | 2650 | 19.755237, −70.564617; 19.267622, −69.730425; 18.568692, −68.348547 | [30] |

| Puerto Rico | 3,057,311 | 6180 | 94.8% | 2929 | 18.494859, −67.135248; 18.010464, −66.563032; 18.436395, −66.002171 | [30] |

| Virgin Islands (U.S.) | 104,917 | 321 | 98.9% | 159 | 17.699028, −64.797495 | [30] |

| British Virgin Islands | 39,369 | 33 | 98.8% | 16 | 18.339107, −64.966938 | [30] |

| Anguilla | 19,079 | 16 | 98.8% | 8 | 18.043635, −63.113343 | [30] |

| Guadeloupe | 390,704 | 551 | 68.9% | 190 | 16.269481, −61.526794 | [32,33] |

| Dominica | 74,656 | 42 | 74.8% | 16 | 15.545482, −61.300085 | [30] |

| Martinique | 371,246 | 438 | 85.1% | 186 | 14.595778, −61.000148 | [32,33] |

| St Lucia | 167,591 | 92 | 99.1% | 46 | 13.736792, −60.949993 | [30] |

| St Vincent and Grenadines | 100,804 | 49 | 73.5% | 18 | 13.163664, −61.151563 | [30] |

| Grenada | 114,299 | 55 | 98.3% | 27 | 12.007409, −61.785788 | [30] |

| Barbados | 303,431 | 311 | 95.9% | 149 | 13.080299, −59.488530 | [30] |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 1,407,460 | 2123 | 99.9% | 1060 | 10.601978, −61.339610; 11.152808, −60.839655 | [30] |

| Guyana | 791,739 | 380 | 97.4% | 185 | 6.504099, −58.252893 | [30] |

| Suriname | 639,759 | 542 | 40.5% | 220 | 5.456538, −55.199946 | [30] |

| French Guiana | 301,099 | 281 | 37% | 52 | 4.822596, −52.364161 | [34] |

| Brazil | 218,689,757 | 195,037 | 11.8% | 58,500 | Appendix B | [30,35] |

| Total | 602,392,300 | 1,368,117 | - | 1,072,283 | - | - |

2.6. Proposed Spatiotemporal Algorithm for Estimation of PV Solar Power under Hurricane Shading

2.7. Assumptions

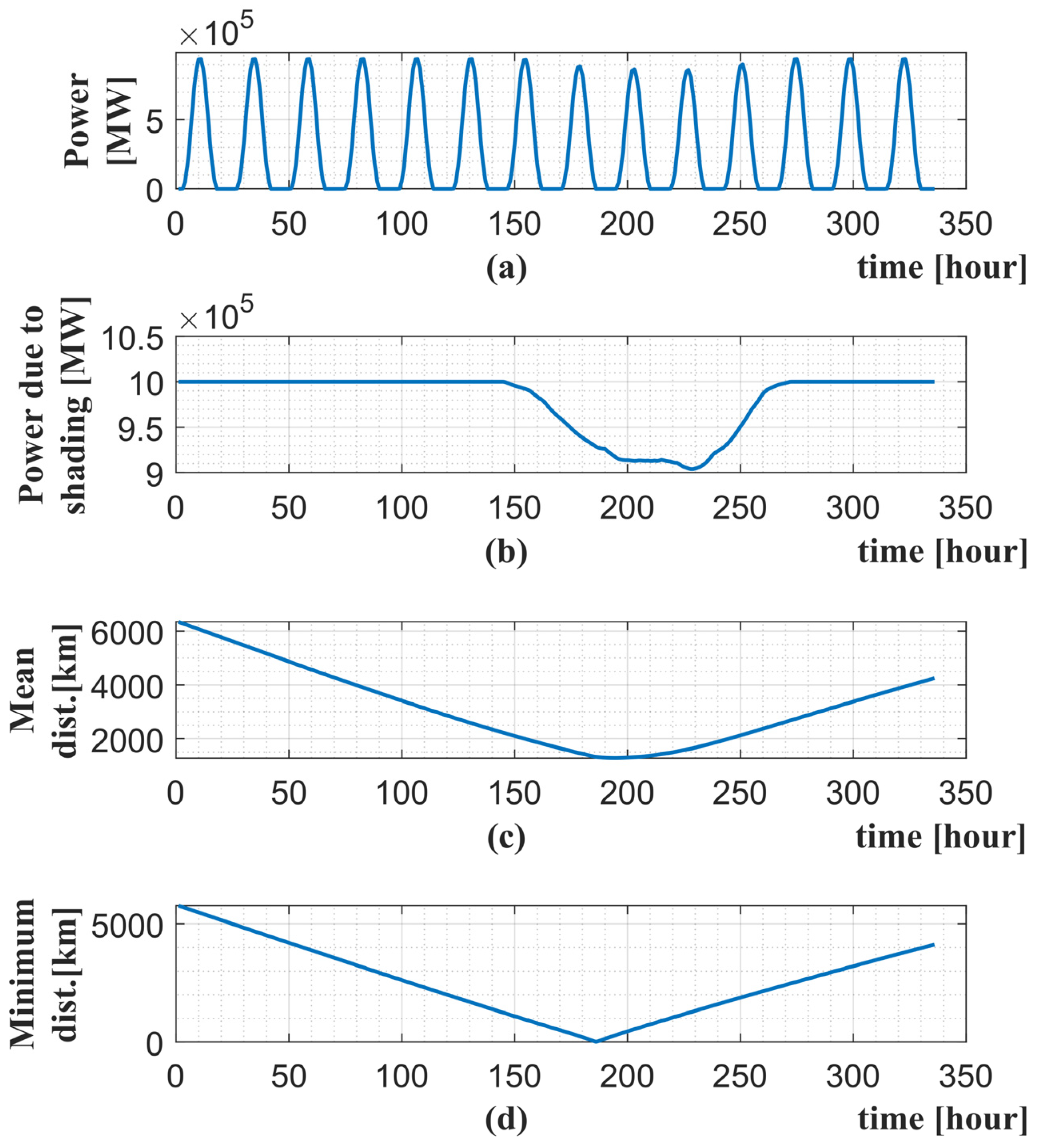

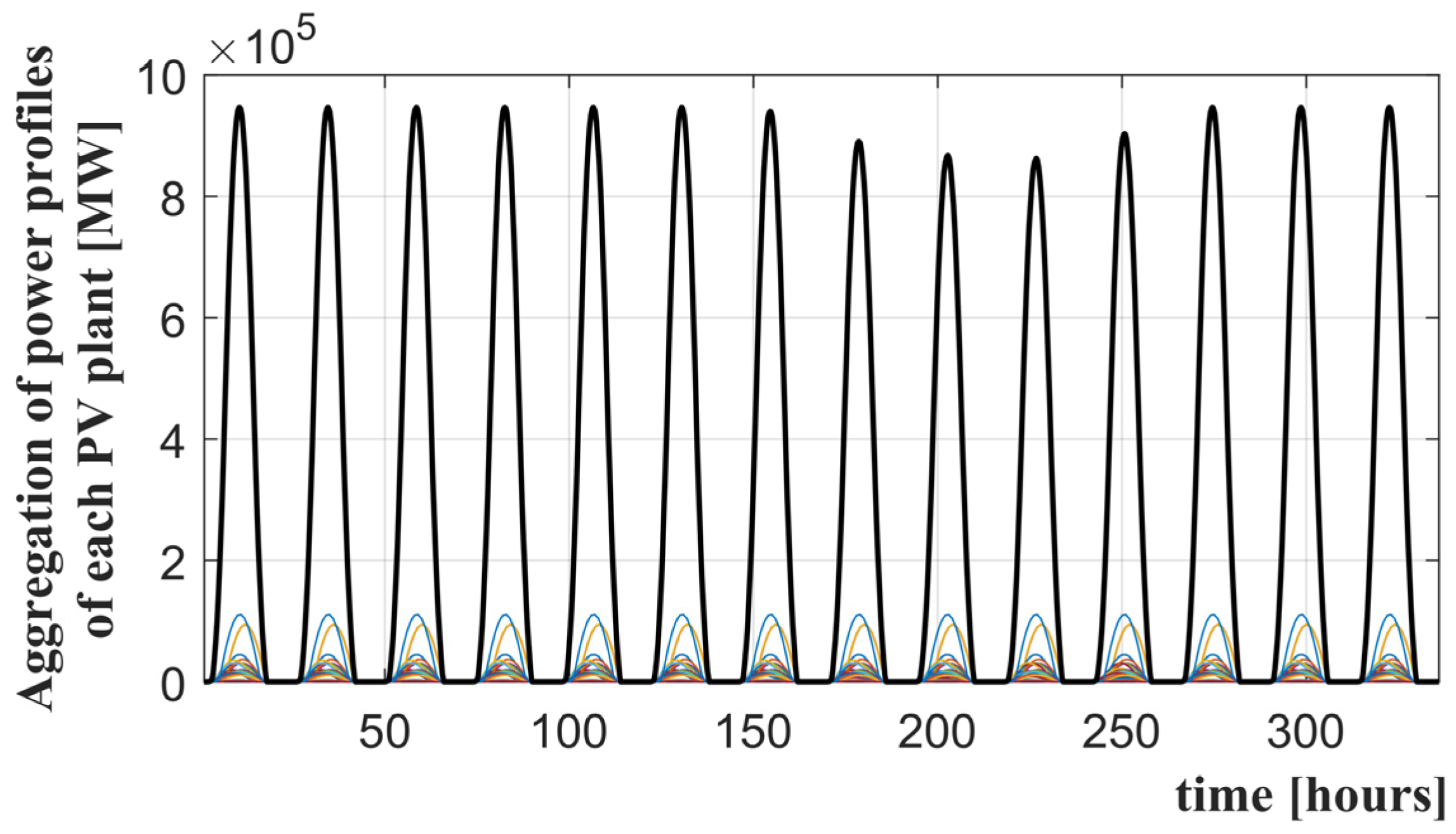

3. Results

- Standalone contiguous U.S. power grid;

- Standalone Caribbean super grid;

- U.S.–Caribbean super grid;

- U.S.–Caribbean–South America super grid.

3.1. Standalone Contiguous U.S. Power Grid

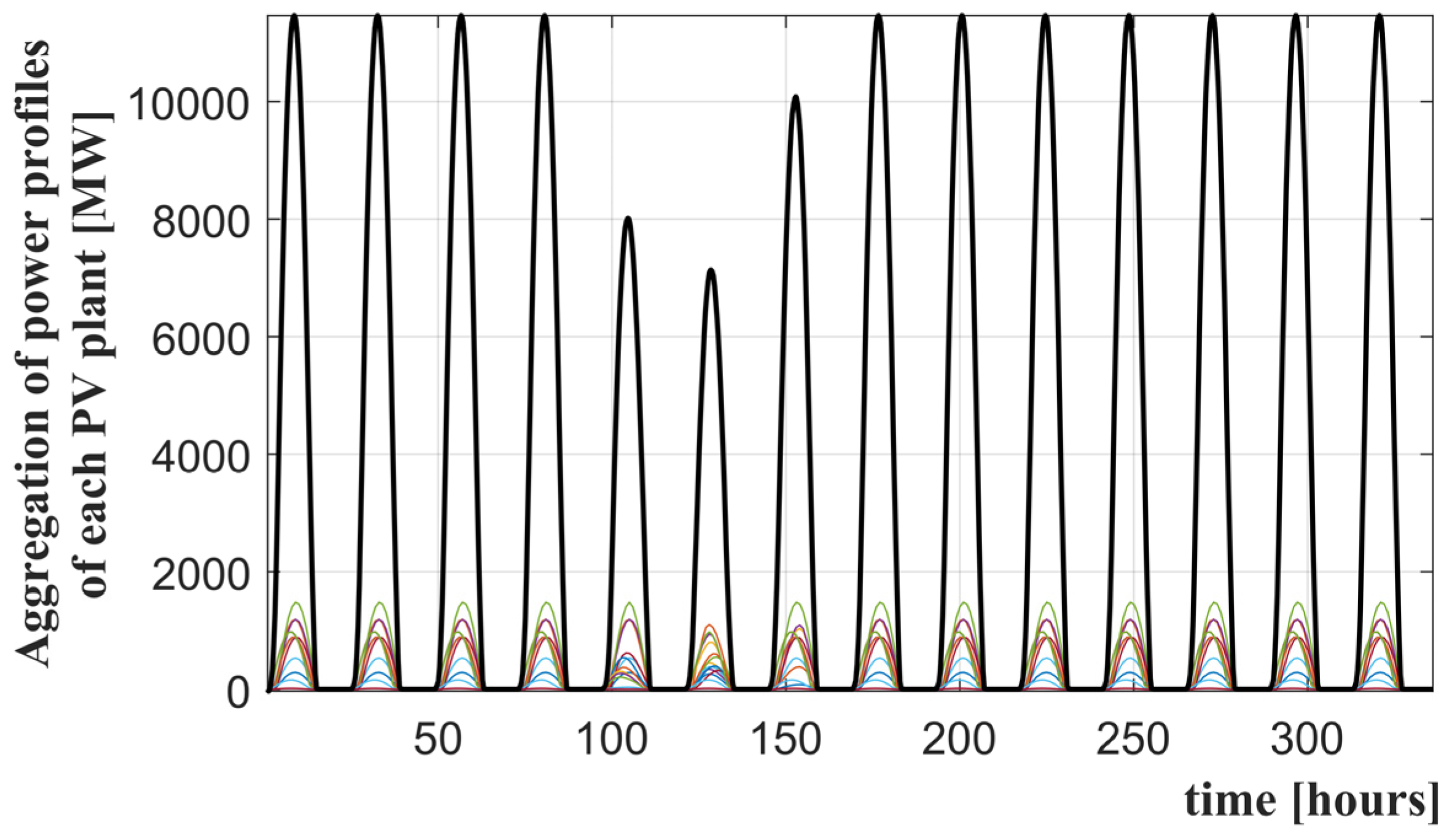

3.2. Standalone Caribbean Super Grid

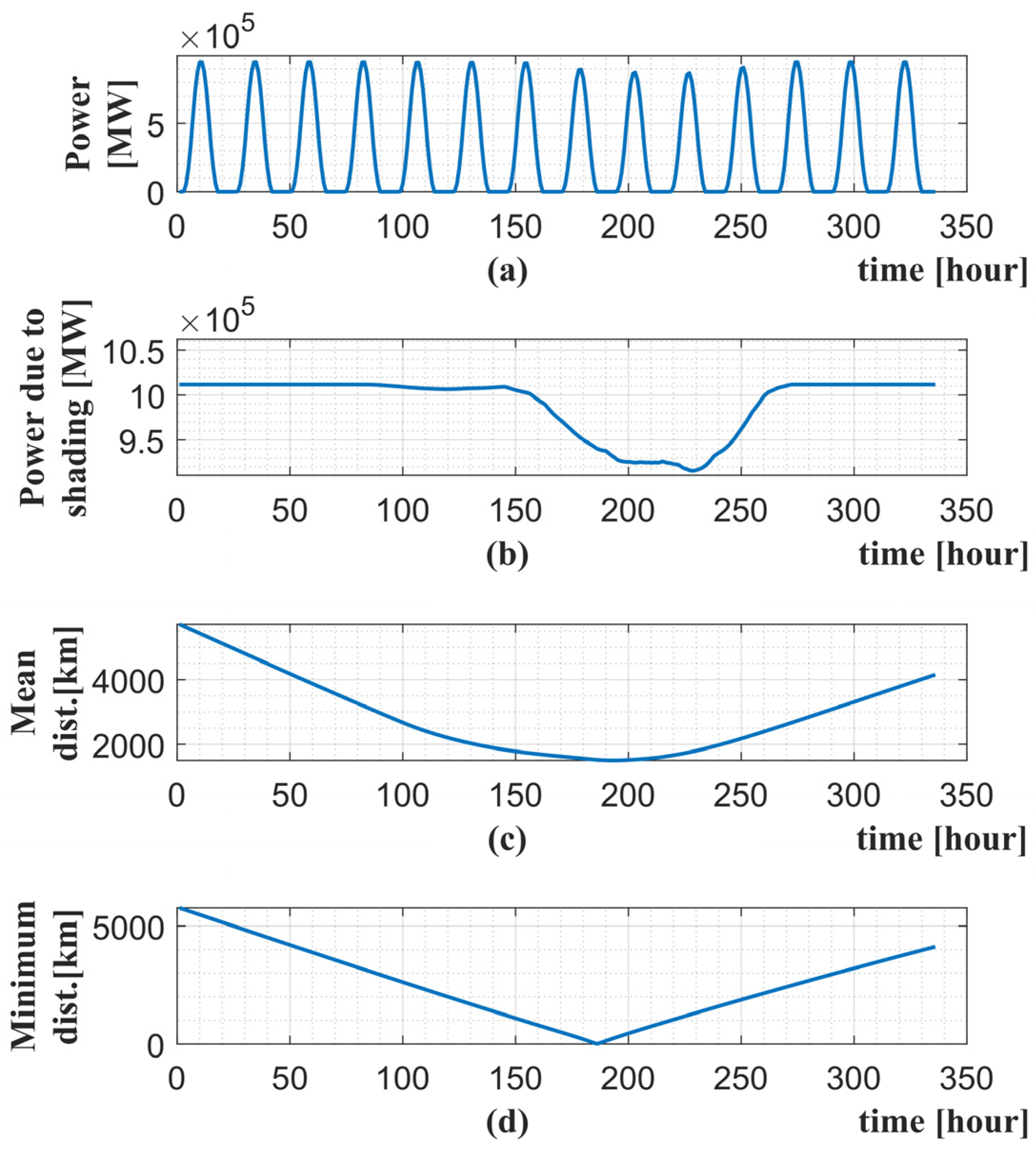

3.3. U.S.–Caribbean Super Grid

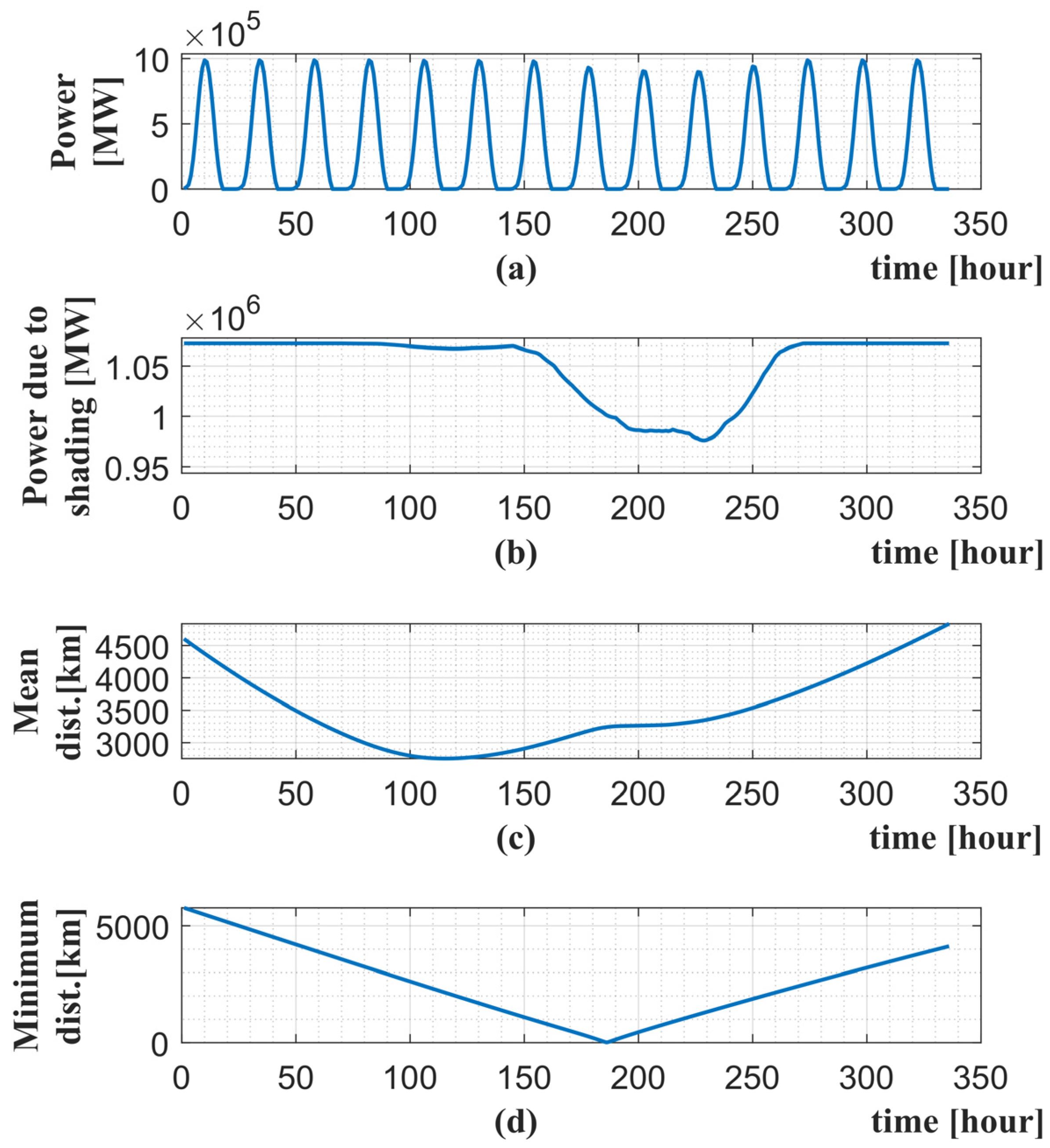

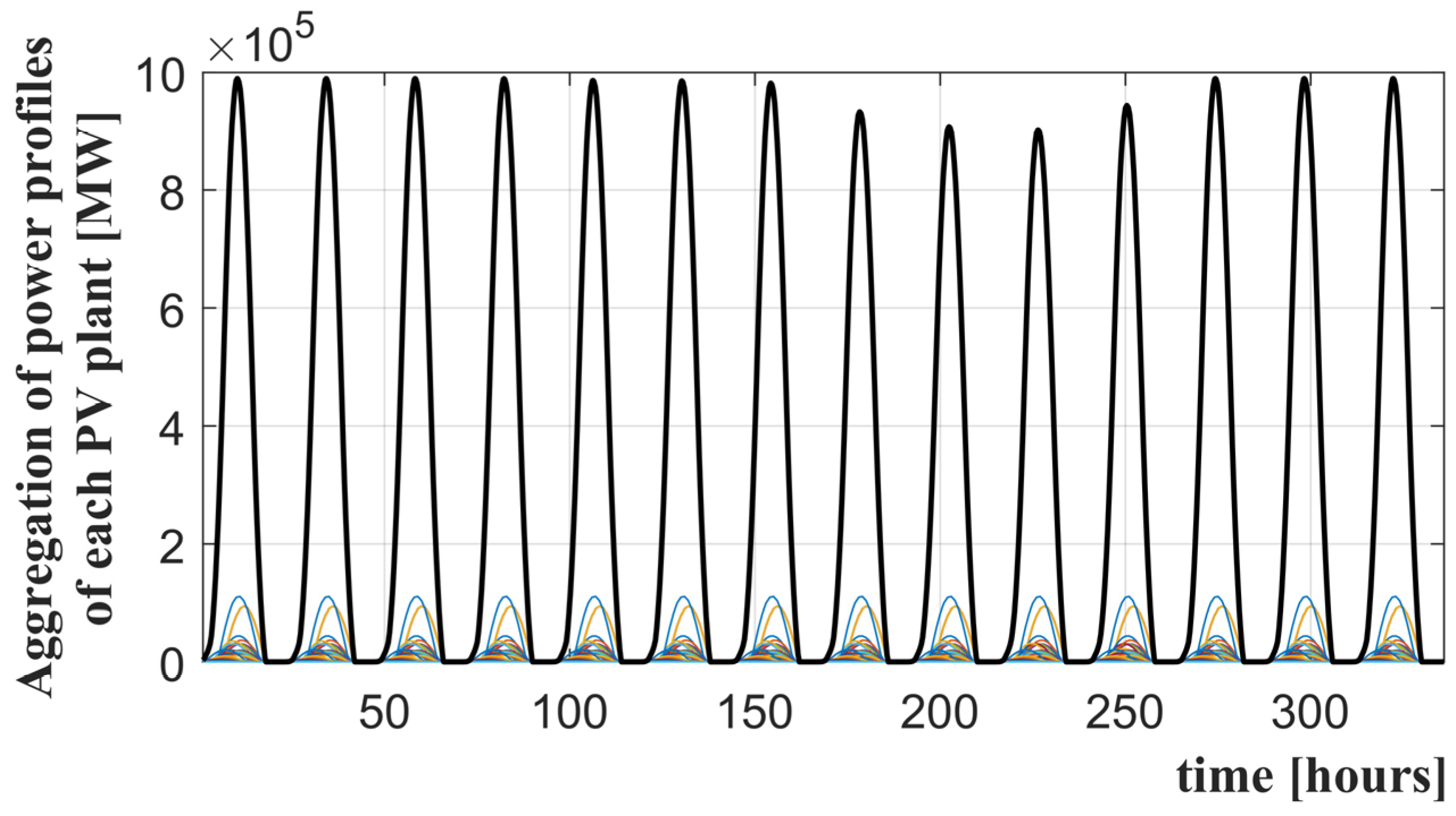

3.4. U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid

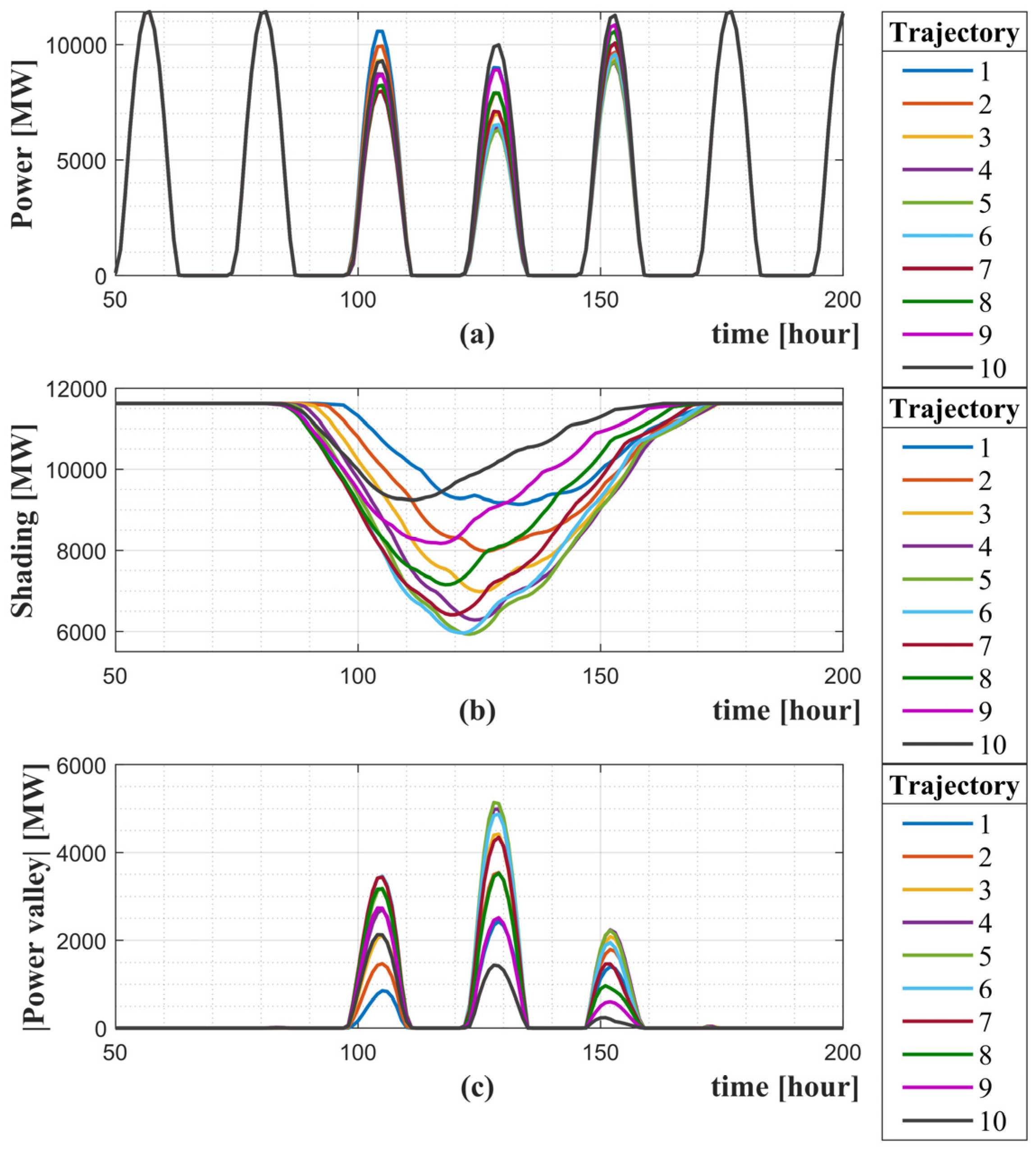

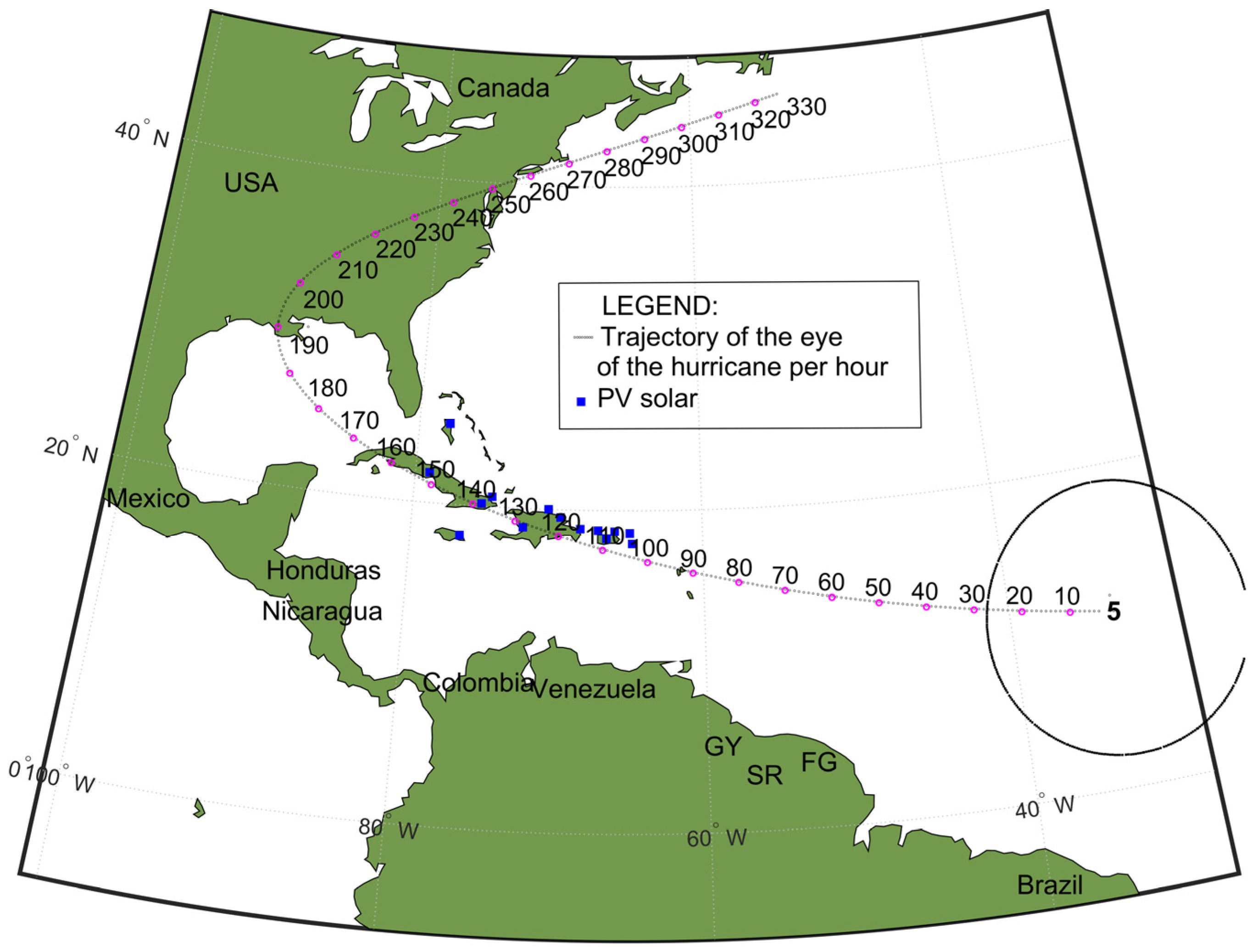

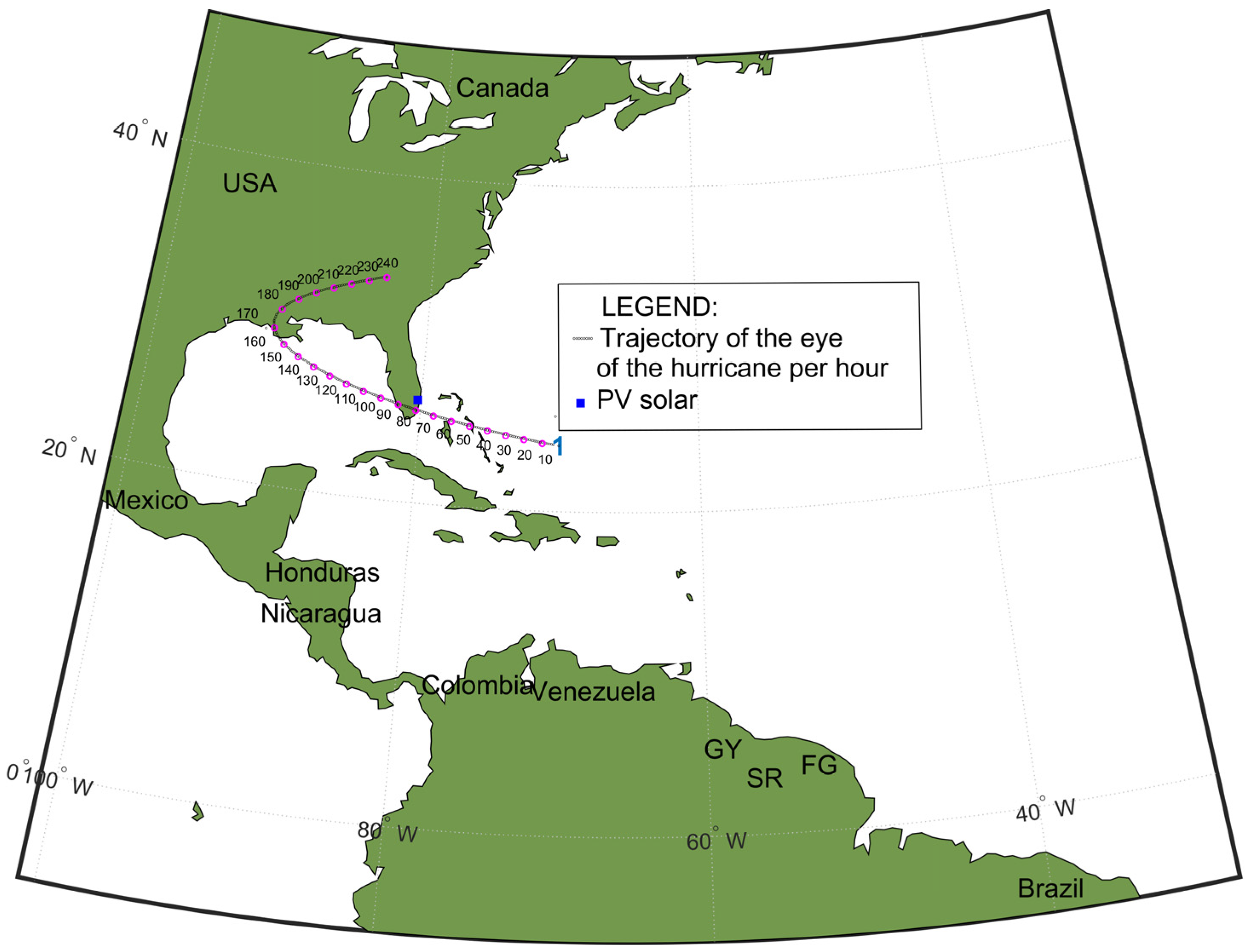

3.5. All Trajectories into the U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid

3.6. All Trajectories into Standalone Caribbean Super Grid

3.7. Comparative Analysis of Scenarios

- Standalone contiguous U.S. power grid: the U.S. is projected to reach 1,000,000 MW in 2050, significantly exceeding the forecasted 72,335 MW for the Caribbean and northern countries and states in South America. In this scenario, the power variability of the standalone contiguous U.S. power grid is not sensitive to hurricanes over the Caribbean.

- Standalone Caribbean super grid: without interconnection to the U.S. or South America grid for power valley filling, a standalone Caribbean super grid would endure the most significant power valley among all schemes. This is primarily due to the arrangement of PV plants on a chain of closely situated islands nearly entirely covered by the shading caused by hurricanes. Additionally, the trajectories of hurricanes typically align parallel to the axis of the Caribbean island chain, prolonging the duration of their impact. Given the projected Caribbean PV capacity by 2050, which is negligible compared to that of the U.S., the Caribbean region would derive substantial benefits from either a U.S.–Caribbean interconnector or a Caribbean–South America interconnector.

- U.S.–Caribbean super grid: the U.S.–Caribbean super grid significantly reduces power variability during hurricanes passing over the Caribbean. The integration of the overseas U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands into an integrated U.S.–Caribbean super grid proves beneficial in mitigating local power valleys.

- U.S.–Caribbean–South America super grid: this interconnectivity scheme adds approximately 60,712 MW of PV capacity, primarily from Brazil (58,500 MW), situated outside the hurricane corridor. Extending the U.S.–Caribbean super grid does not significantly reduce the overall relative power variability. More PV solar power capacity or other renewable energy sources (e.g., wind or hydropower) in South America would be needed to significantly smooth the power variability in hurricane-prone areas. Connecting the U.S.-Caribbean super grid to South America would provide energy security by an alternative power supply in the event of the disconnection of a segment of the Caribbean super grid.

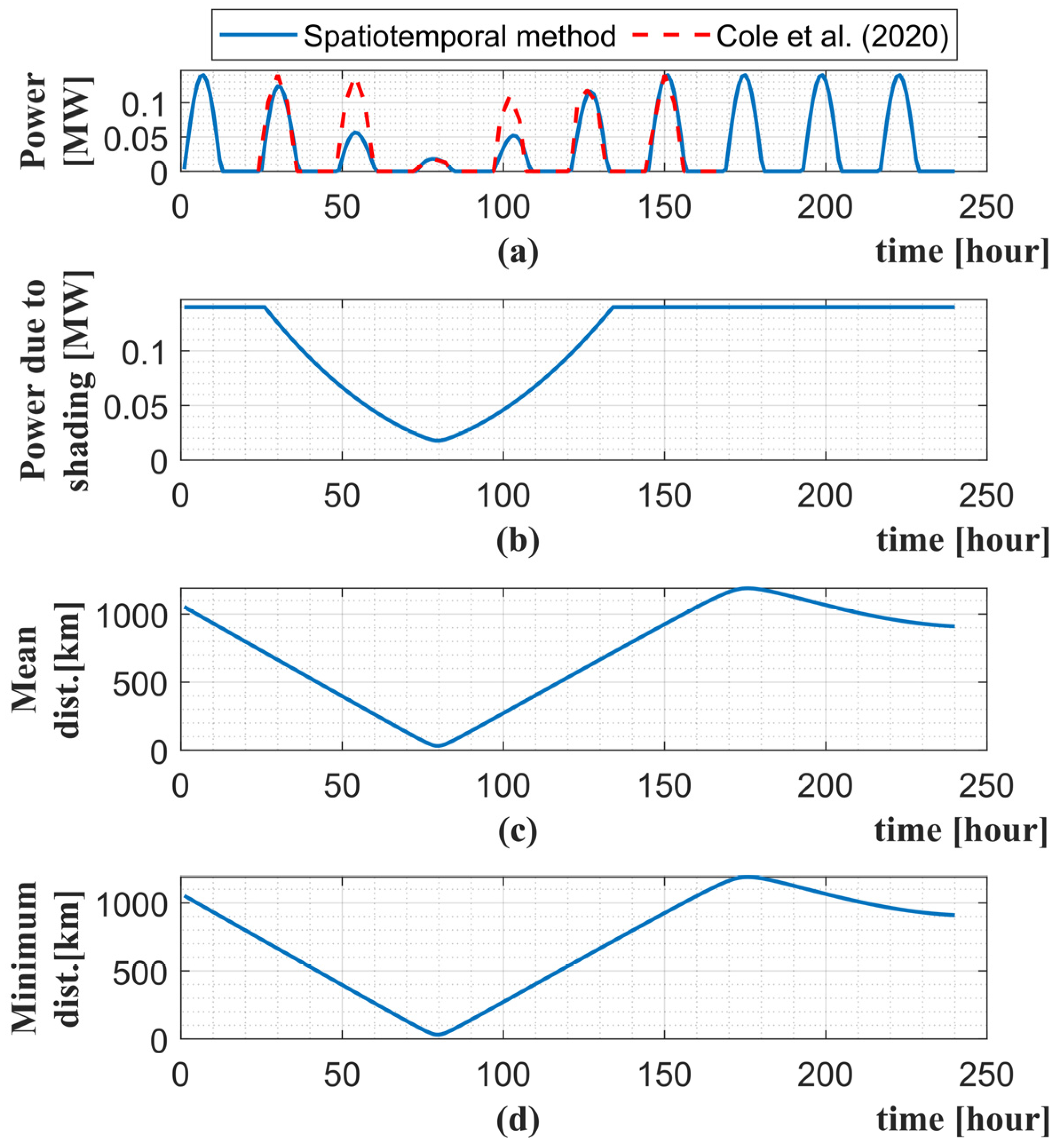

4. Analysis of Consistency

5. Conclusions

5.1. The Contributions of this Research

5.2. Limitations of This Work and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| W/m2 | Extraterrestrial solar energy flux | |

| - | Hurricane shading slope factor | |

| - | Hurricane shading slope factor | |

| - | Parabola coefficient | |

| - | Albedo | |

| h | Apparent or true solar time | |

| rad | Equation of time (relative to the day number N in the year) | |

| - | Hurricane shading short-distance correction factor | |

| - | Hurricane shading short-distance correction factor | |

| - | Parabola coefficient | |

| Tilt angle of PV module | ||

| - | Hurricane shading scale factor | |

| - | Hurricane shading scale factor | |

| - | Parabola coefficient | |

| - | Hurricane category | |

| km | Distance to the hurricane eye. | |

| - | Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) Decay | |

| Angle of declination | ||

| % | PV solar power variability | |

| minutes | Difference between apparent and mean solar times | |

| - | Functional forms | |

| % | Fossil fuel dependence factor | |

| % | PV expansion factor | |

| - | Derating factor of PV cell | |

| GHI | kW/m2 | Global Horizontal Irradiance |

| kW/m2 | Beam solar irradiation by collector on a horizontal surface | |

| kW/m2 | Beam solar irradiation in the sky | |

| kW/m2 | Diffuse solar irradiation | |

| kW/m2 | Reflected solar irradiation | |

| kW/m2 | Incident radiation at standard test conditions (equal to 1 kW/m2) | |

| kW/m2 | Total solar irradiation absorbed by fixed tilted PV module | |

| 1/C | Temperature coefficient of PV panel (3.5 × 10−3 1/C), | |

| p.u. | Irradiance for per unit calculation in clear sky | |

| % | Clearness factor | |

| Latitude of the PV plant | ||

| Longitude of the PV plant | ||

| Local mean sidereal time, degrees | ||

| day | Day number in a year | |

| NOAA | - | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| MW | PV power in pre-hurricane conditions | |

| MW | Minimum instantaneous peak PV power | |

| MWac | Photovoltaic power capacity | |

| MW | Total power capacity of a country | |

| PV | - | Photovoltaic |

| km | Relative distance to the hurricane eye | |

| km | Radius of outermost closed isobar. | |

| % | Ratio between global solar energy on a horizontal surface and global solar energy on a tilted surface. | |

| % | Ratio between diffuse solar energy on a horizontal surface and diffuse solar energy on a tilted surface. | |

| % | Factor of reflected solar energy on a tilted surface | |

| °C | Ambient temperature (in °C) | |

| °C | Solar time correction | |

| °C | PV cell temperature (in °C) | |

| °C | PV cell temperature at standard test conditions (equal to 25 °C) | |

| h | Time difference with reference to GMT | |

| h | Time of sunrise with correction | |

| h | Time of sunset with correction | |

| ° | Hour angle degree | |

| ° | Sunrise hour angle time | |

| ° | Sunset hour angle time | |

| ° | Latitude of hurricane eye in parabola trajectory | |

| ° | Longitude of hurricane eye in parabola trajectory |

Appendix A

- : latitude of the PV plant;

- : longitude of the PV plant;

- N: day number 258, corresponding to 15 September, in the middle of the U.S. hurricanes season;

- The remaining variables are described in the list of abbreviations.

Appendix B

| U.S. States | Cumulative PV Capacity [MW ac] [40] | Latitude, Longitude | Brazil States | Cumulative PV Capacity [MW ac] [41] | Latitude, Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 30,738 | 36.232171, −119.916045; 34.795990, −118.446496; 35.382405, −120.058481 | Minas Gerais | 6468 | −17.127722, −43.844568 |

| Texas | 13,404 | 31.095329, −102.344823; 30.241752, −97.513868 29.217125, −95.658233 30.706400, −96.068545 | Bahia | 2402 | −12.598216, −44.106217 |

| Florida | 7838 | 27.763334, −82.234079 30.515422, −86.514052 30.449714, −83.198413 30.289455, −82.777271 | Piaui | 3050 | −10.098598, −45.258506 |

| North Carolina | 6371 | 36.027904, −80.300748 36.027838, −80.300811 34.223174, −77.945766 | Sao Paulo | 1162 | −21.295295, −49.935380 |

| Arizona | 4806 | 33.266410, −111.616842 | Ceara | 1536 | −3.988918, −38.393514 |

| Nevada | 4008 | 35.787342, −114.959010 | Pernambuco | 1158 | −9.070659, −38.146141 |

| New York | 3906 | 42.750417, −73.760531 | Rio Grande do Norte | 1383 | −5.566330, −37.028634 |

| Georgia | 3676 | 31.415000, −84.836573 32.999522, −85.035689 | Paraiba | 811 | −6.840431, −36.930855 |

| New Jersey | 3413 | 40.334604, −74.646582 | Rio Grande do Sul | 23 | −29.663366, −50.589770 |

| Massachusetts | 3257 | 42.445847, −72.622222 42.402297, −71.007982 | Mato Grosso | 22 | −15.285470, −56.267769 |

| Virginia | 3032 | 36.792318, −76.668125 37.960675, −75.555078 | Parana | 16 | −25.341358, −49.094838 |

| Colorado | 2154 | 38.626906, −104.663352 | Para | 16 | −3.224113, −52.255189 |

| Utah | 2001 | 39.843394, −111.884718 | Roraima | 14 | 2.815288, -60.683043 |

| Illinois | 1815 | 40.081691, −88.243801 | Espirito Santo | 13 | −19.402187, −39.990263 |

| South Carolina | 1602 | 32.878153, −79.972821 | Santa Catarina | 12 | −26.824511, −52.221743 |

| Maryland | 1496 | 39.112493, −75.963808 | Mato Grosso do Sul | 11 | −21.927429, −54.867826 |

| Minnesota | 1309 | 45.097138, −93.644808 | Tocantins | 6 | −10.145414, −48.316027 |

| Hawaii | - | Not contiguous U.S. | Rio de Janeiro | 5 | −21.266003, −41.761048 |

| New Mexico | 1173 | 35.048635, −106.529196 | Goias | 5 | −15.385015, −49.090919 |

| Louisiana [42] | 345 | 30.676825, −91.392683 | Amapa | 4 | −0.002117, −51.083712 |

| Mississippi [42] | 300 | 30.676447, −91.392408 | Alagoas | 4 | −9.571945, −35.771952 |

| Alabama [42] | 175 | 30.675551, −91.391077 | Maranhao | 2 | -3.591578, −43.937995 |

| Tennessee [42] | 150 | 32.510525, −89.730594 | Roraima | 2 | 2.815280, −60.683045 |

| Others | 12,039 | 41.233289, −110.753551 | Acre | 1 | −10.010626, −67.759293 |

| Distrito Federal | 1 | −15.781504, −48.122397 | |||

| Amazonas | 1 | −2.636500, −60.949138 | |||

| Sergipe | 1 | −10.984704, −37.054391 | |||

| Total PV | 109,008 MW | in December 2022 [40,42] | Total PV | 18,129 MW | in October 2023 [41] |

| Total PV | 1,000,000 MW | projected to 2050 [31] | Total PV | 58,500 MW | projected to 2050 [35] |

References

- Méndez-Tejeda, R.; Hernández-Ayala, J.J. Links between climate change and hurricanes in the North Atlantic. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, W.; Greer, D.; Lamb, K. The potential for using local PV to meet critical loads during hurricanes. Sol. Energy 2020, 205, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceferino, L.; Lin, N.; Xi, D. Stochastic modeling of solar irradiance during hurricanes. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 2681–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transitions; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitions (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Bompard, E.; Fulli, G.; Ardelean, M.; Masera, M. It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s a…Supergrid!: Evolution, Opportunities, and Critical Issues for Pan-European Transmission. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2014, 12, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianel, G.; Ergun, H.; Van Hertem, D. A Multi-GW Energy Hub for Southern Europe: The Mediterranean Energy Island Proposal. In Proceedings of the 2023 AEIT HVDC International Conference (AEIT HVDC), Rome, Italy, 25–26 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Mekhilef, S.; Shah, R.; Mithulananthan, N. Investigation into transmission options for cross-border power trading in ASEAN power grid. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itiki, R.; Manjrekar, M.; Di Santo, S.G.; Machado, L.F.M. Topology Design Method for Super Grids based on experiences in China and North America. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 17–20 February 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Dong, H.; Huang, H. Debates on ultra-high-voltage synchronous power grid: The future super grid in China? IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2015, 9, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, M.; Minnebo, P. The suitability of seas and shores for building submarine power interconnections. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvins, A.; Sereno, L.; Ardelean, M.; Covrig, C.-F.; Efthimiadis, T.; Minnebo, P. Submarine power cable between Europe and North America: A techno-economic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namjil, E.; Komoto, K. Strategies for Implementing of Very Large Scale Solar and Wind Power Plants in the Gobi Desert for the Northeast Asia Regional Energy Market. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 49th Photovoltaics Specialists Conference (PVSC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 5–10 June 2022; pp. 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jung, T.Y. Embarking on the Asia Supergrid: Trade impact of carbon pricing on regional sustainability in northeast Asia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itiki, R.; Manjrekar, M.; Di Santo, S.G. Technical feasibility of Japan-Taiwan-Philippines HVdc interconnector to the Asia Pacific Super Grid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Siala, K.; de La Rúa, C.; Massier, T.; Ahmed, A.; Hamacher, T. Life Cycle Climate Change Impact of a Cost-Optimal HVDC Connection to Import Solar Energy from Australia to Singapore. Energies 2021, 14, 7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itiki, R.; Manjrekar, M.; Di Santo, S.G. Proposed Extension of the U.S.–Caribbean Super Grid to South America for Resilience during Hurricanes. Energies 2024, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, N.A.; Ríos, M.A. Planning a Latin America SuperGrid: A First Approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE ANDESCON, Santiago de Cali, Colombia, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.E.; Clack, C.T.M.; Alexander, A.; Dunbar, A.; Wilczak, J.; Xie, Y. Future cost-competitive electricity systems and their impact on US CO2 emissions. Nature Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlela, N.W.; Davidson, I.E. Power Planning for a Smart Integrated African Super-Grid. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference (SAUPEC), Durban, South Africa, 25–27 January 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itiki, R.; Manjrekar, M.; Di Santo, S.G.; Itiki, C. Method for spatiotemporal wind power generation profile under hurricanes: U.S.-Caribbean super grid proposition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhs, J.W.; Parvania, M. Stochastic Spatio-Temporal Hurricane Impact Analysis for Power Grid Resilience Studies. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 18–21 February 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, T.; Lawrence, T.; Hall, M. Drivers and barriers to public acceptance of future energy sources and grid expansion in the United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 126, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, T.; Elmenreich, W. Modeling of Photovoltaic Systems Using MATLAB: Simplified Green Codes, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, Z.; Santarelli, M.; Marocco, P.; Ferrero, D.; Zahid, U. Techno-economic feasibility analysis of Renewable-fed Power-to-Power (P2P) systems for small French islands. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 255, 115368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven II, L.J.; Berg, R.; Hagen, A. Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Michael (AL142018) 7–11 October 2018, National Hurricane Center 17 May (2019). Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL142018_Michael.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Pasch, R.J.; Brown, D.P.; Blake, E.S. Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Charley 9–14 August 2004, National Hurricane Center. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL032004_Charley.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Pasch, R.J.; Blake, E.S.; Cobb III, H.D.; Roberts, D.P. Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Wilma 15–25 October 2005, National Hurricane Center, 12 January. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL252005_Wilma.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- U.S. Department of Commerce. National Weather Service, North Atlantic Hurricane Tracking Chart 2020. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tracks/tracks-at-2020.png (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Dornan, M.; Shah, K.U. Energy policy, aid, and the development of renewable energy resources in Small Island Developing States. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA. The World Factbook—Explore All Countries; Central Intelligence Agency. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- NREL. Solar Futures Study; National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/Solar%20Futures%20Study.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Rakotoson, V.; Praene, J.P. A life cycle assessment approach to the electricity generation of French overseas territories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notton, G.; Voyant, C.; Duchaud, J.L. Difficulties of Solar PV Integration in Island Electrical Networks—Case Study in the French Islands. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 111, 06028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillot, B.; Al-Kurdi, N.; Gervet, C.; Linguet, L. Optimizing operational costs and PV production at utility scale: An optical fiber network analogy for solar park clustering. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, N.M.; Oliveira, C.B.; Cunha, D. Photovoltaic electronic waste in Brazil: Circular economy challenges, potential and obstacles. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabb, R.D.; Rhome, J.R.; Brown, D.P. Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Katrina 23–30 August 2005, National Hurricane Center, 4 January 2023. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL122005_Katrina.pdf. (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- NOAA. 2005 Major Hurricane KATRINA (2005236N23285), International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS), National Centers for Environmental Information. Available online: https://ibtracs.unca.edu/index.php?name=v04r00-2005236N23285 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Roumpakias, E.; Stamatelos, A. Comparative performance analysis of grid-connected photovoltaic system by use of existing performance models. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 150, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.H.; Jordan, R.C. The long-term average performance of flat-plate solar-energy collectors: With design data for the US its outlying possessions and Canada. Sol. Energy 1963, 7, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.; Dummit, K.; Zuboy, J.; Margolis, R. Spring 2023 Solar Industry Update; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 27 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANEEL. Installed Capacity by State, Superintendency of Concessions, Permits and Authorizations for Electrical Energy Services (SCE). Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNjc4OGYyYjQtYWM2ZC00YjllLWJlYmEtYzdkNTQ1MTc1NjM2IiwidCI6IjQwZDZmOWI4LWVjYTctNDZhMi05MmQ0LWVhNGU5YzAxNzBlMSIsImMiOjR9 (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Solar Energy Industry Association. Project Location Map. 2023. Available online: https://www.seia.org/research-resources/major-solar-projects-list. (accessed on 17 October 2023).

| Parameters | Description | Michael (2018) [25] | Charley (2004) [26] | Wilma (2005) [27] | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hurricane category | 5 | 4 | 3 | [20] | |

| slope factor | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.97 | [3] | |

| slope factor | 0.0965 | 0.0965 | 0.0965 | [3] | |

| short-distance correction factor | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.15 | [3] | |

| short-distance correction factor | −0.126 | −0.126 | −0.126 | [3] | |

| scale factor | 2.48 | 2.48 | 2.48 | [3] | |

| scale factor | −0.139 | −0.139 | −0.139 | [3] | |

| for onshore | radii of the outermost closed isobar | 150 nautical miles (278 km) | 100 nautical miles (185 km) | 250 nautical miles (463 km) | NOAA [25,26,27] |

| for offshore | radii of the outermost closed isobar | 200 nautical miles (370 km) | 100 nautical miles (185 km) | 300 nautical miles (556 km) | NOAA [25,26,27] |

| d, and | absolute distance from hurricane eye, relative distance from hurricane eye, and functional form | recalculated after each step | recalculated after each step | recalculated after each step | [3] |

| simulation time step | 1 h | 1 h | 1 h | [20] | |

| hurricane translational speed | 9.722 m/s | 12.5 m/s | 13.333 m/s | [20] |

| Parameters | Specification and Environment Variables | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| PV module technology | Monocrystalline | [3] |

| Tilt type | Fixed open rack (hurricane resistant) | [3] |

| Tilt angle | Made equal to plant latitude (degrees) | [3] |

| Azimuth orientation | 180 degrees (Northern Hemisphere) 0 degrees (Southern Hemisphere) | [3] |

| PV-rated ac power output | Appendix B |

| Track # | [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | −69.9563 | 30 | −100.0 |

| 2 | 8 | −70.2564 | 30 | −97.7778 |

| 3 | 9 | −33.1111 | 30 | −95.5556 |

| 4 | 10 | −33.1667 | 30 | −93.3333 |

| 5 | 11 | −33.2222 | 30 | −91.1111 |

| 6 | 12 | −33.2778 | 30 | −88.8889 |

| 7 | 13 | −33.3333 | 30 | −86.6667 |

| 8 | 14 | −33.3889 | 30 | −84.4444 |

| 9 | 15 | −33.4444 | 30 | −82.2222 |

| 10 | 16 | −33.5 | 30 | −80 |

| Values | Standalone U.S. Power Grid | Standalone Caribbean Super Grid | U.S.–Caribbean Super Grid | U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory number | #7 | #7 | #7 | #7 |

| Total number of PV solar plants | 36 | 14 | 50 | 90 |

| Total PV capacity [MW] | 1,000,000 | 11,623 | 1,011,623 | 1,072,335 |

| Figures | Figure 6 and Figure 7 | Figure 9 and Figure 10 | Figure 11 and Figure 12 | Figure 13 and Figure 14 |

| Power valley in the Caribbean: | - | - | - | - |

| [MW] | N.A. | 11,463 | 955,983 | 989,600 |

| [MW] | N.A. | 7135 | 952,087 | 985,563 |

| [%] | N.A. | 37.8% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Power valley in the contiguous U.S.: | - | - | - | |

| [MW] | 946,114 | N.A. | 955,983 | 989,600 |

| [MW] | 861,819 | N.A. | 871,316 | 901,893 |

| [%] | 8.9% | N.A. | 8.9% | 8.9% |

| Trajectory # | States | Spatial Density of PV Capacity [MW/km2] | Instantaneous Power Valley [MW] | Capacity Power Valley [MW] | Capacity Power Valley [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Texas | 0.0193 (2) | 63,156 (2) | 66,700 (1) | 6.7% |

| 2 | Texas | 0.0193 (2) | 88,851 (9) | 79,690 (3) | 8.1% |

| 3 | Texas | 0.0193 (2) | 85,178 (5) | 90,150 (4) | 9.1% |

| 4 | Louisiana | 0.0025 (3) | 88,455 (7) | 95,130 (5) | 9.6% |

| 5 | Louisiana | 0.0025 (3) | 78,304 (3) | 101,850 (9) | 10.3% |

| 6 | Alabama | 0.0013 (4) | 88,563 (8) | 102,110 (10) | 10.3% |

| 7 | Florida | 0.0460 (1) | 87,707 (6) | 96,090 (6) | 9.7% |

| 8 | Florida | 0.0460 (1) | 81,970 (4) | 98,880 (8) | 10.0% |

| 9 | Florida | 0.0460 (1) | 90,249 (10) | 98,130 (7) | 9.9% |

| 10 | Off the coast of Florida | 0 (5) | 55,656 (1) | 79,310 (2) | 8.0% |

| Trajectory # | Instantaneous Power Valley [MW] | Capacity Power Valley [MW] | Capacity Power Valley [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2414 | 2325 | 20.3% |

| 2 | 3543 | 3482 | 30.4% |

| 3 | 4439 | 4477 | 39.1% |

| 4 | 5026 | 5177 | 45.2% |

| 5 | 5145 | 5530 | 48.2% |

| 6 | 4891 | 5500 | 48.0% |

| 7 | 4329 | 5051 | 44.1% |

| 8 | 3515 | 4306 | 37.6% |

| 9 | 2754 | 3288 | 28.7% |

| 10 | 2143 | 2223 | 19.4% |

| Parameters | Description | Katrina (2005) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| hurricane category | 1 (in Florida) | [36] | |

| slope factor | 1.97 | [3] | |

| slope factor | 0.0965 | [3] | |

| short-distance correction factor | 1.15 | [3] | |

| short-distance correction factor | −0.126 | [3] | |

| scale factor | 2.48 | [3] | |

| scale factor | −0.139 | [3] | |

for onshore | radii of the outermost closed isobar | 150 nautical miles (277 km) | [37] |

for offshore | radii of the outermost closed isobar | 130 nautical miles (241 km) | [37] |

and | absolute distance from hurricane eye, relative distance from hurricane eye, and functional form | recalculated after each hurricane step | - |

| simulation time step | 1 h | [16], | |

| hurricane translational speed | 4.11–5.14 m/s (8–10 knots) | [37] | |

| - | trajectory shape | parabola crossing the border of Broward/Miami-Dade County, FL | [16,36] |

| Method | Spatiotemporal Method | Cole et al.’s Measurements [2] | Difference: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days under shading | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Pre-hurricane power [kW ac] | 140 (100%) | 140 (100%) | 0 |

| Day 1’s noon peak power [kW ac] | 123.8 (88%) | 140 (100%) | −16.2 |

| Day 2’s noon peak power [kW ac] | 56.5 (40%) | 140 (100%) | −83.5 |

| Day 3’s noon peak power [kW ac] | 18.1 (13%) | 18 (13%) | 0.1 |

| Day 4’s noon peak power [kW ac] | 52.1 (37%) | 110 (79%) | −57.9 |

| Day 5’s noon peak power [kW ac] | 113.2 (81%) | 118 (84%) | −4.8 |

| Peak average [kW ac] | 72.7 (52%) | 82.0 (59%) | −9.3 (−6.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Itiki, R.; Stenvig, N.; Kuruganti, T.; Di Santo, S.G. Method for Spatiotemporal Solar Power Profile Estimation for a Proposed U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid under Hurricanes. Energies 2024, 17, 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17071545

Itiki R, Stenvig N, Kuruganti T, Di Santo SG. Method for Spatiotemporal Solar Power Profile Estimation for a Proposed U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid under Hurricanes. Energies. 2024; 17(7):1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17071545

Chicago/Turabian StyleItiki, Rodney, Nils Stenvig, Teja Kuruganti, and Silvio Giuseppe Di Santo. 2024. "Method for Spatiotemporal Solar Power Profile Estimation for a Proposed U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid under Hurricanes" Energies 17, no. 7: 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17071545

APA StyleItiki, R., Stenvig, N., Kuruganti, T., & Di Santo, S. G. (2024). Method for Spatiotemporal Solar Power Profile Estimation for a Proposed U.S.–Caribbean–South America Super Grid under Hurricanes. Energies, 17(7), 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17071545