Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection of Low-Intensity Noise Fiber Laser Based on Polarized Light Demodulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

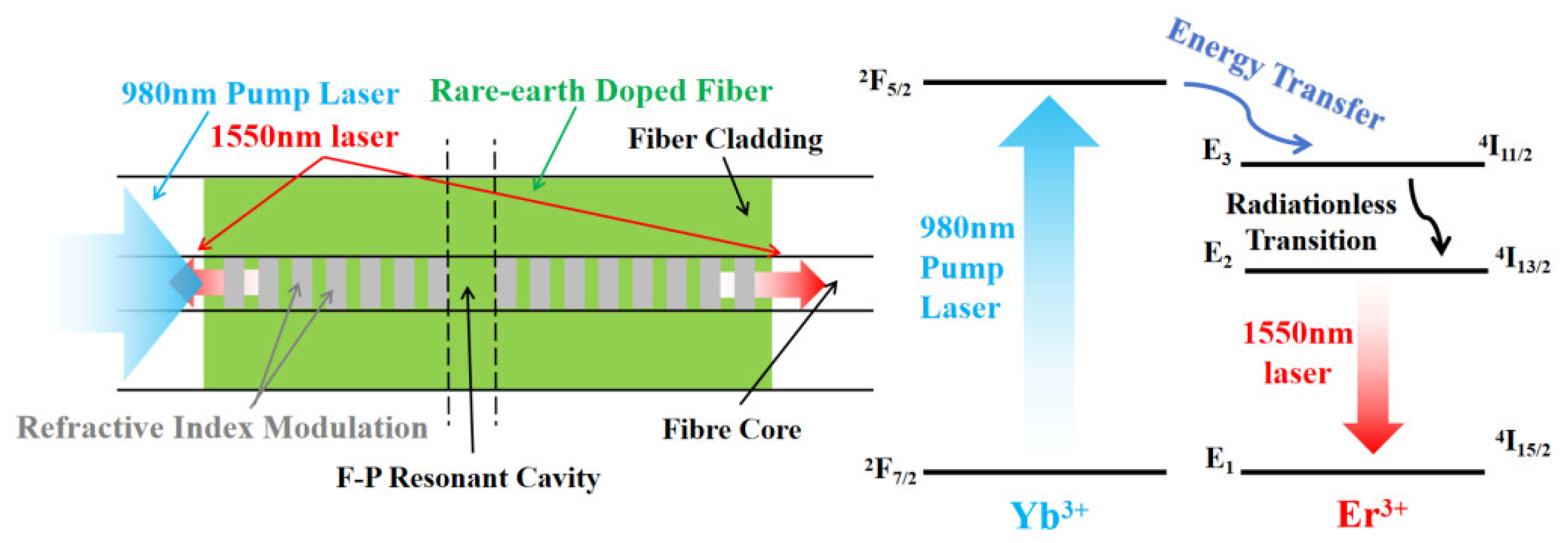

2. Mechanism of DFB Polarized Light Demodulation System

2.1. DFB Theoretical Structure Model

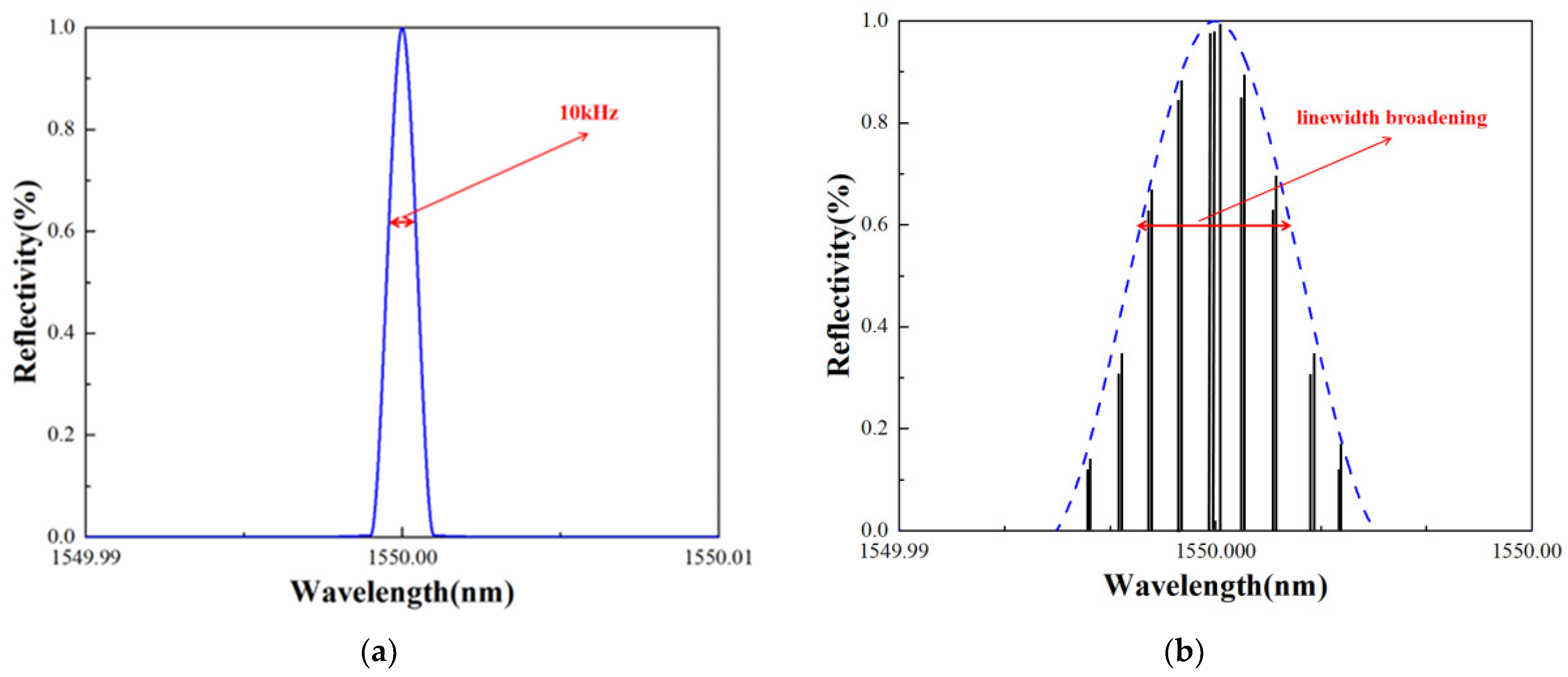

2.2. Principle of Polarized Light Demodulation System

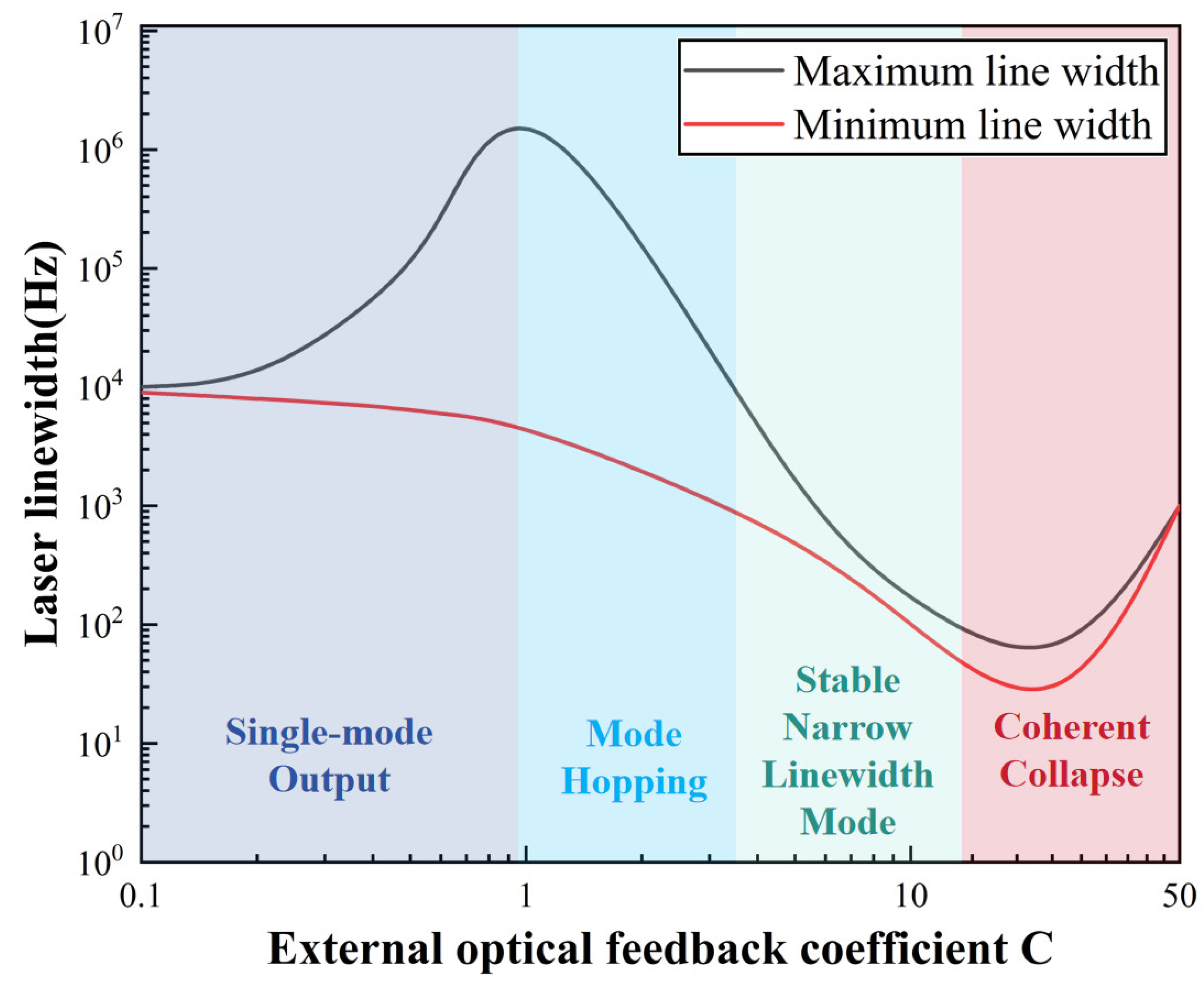

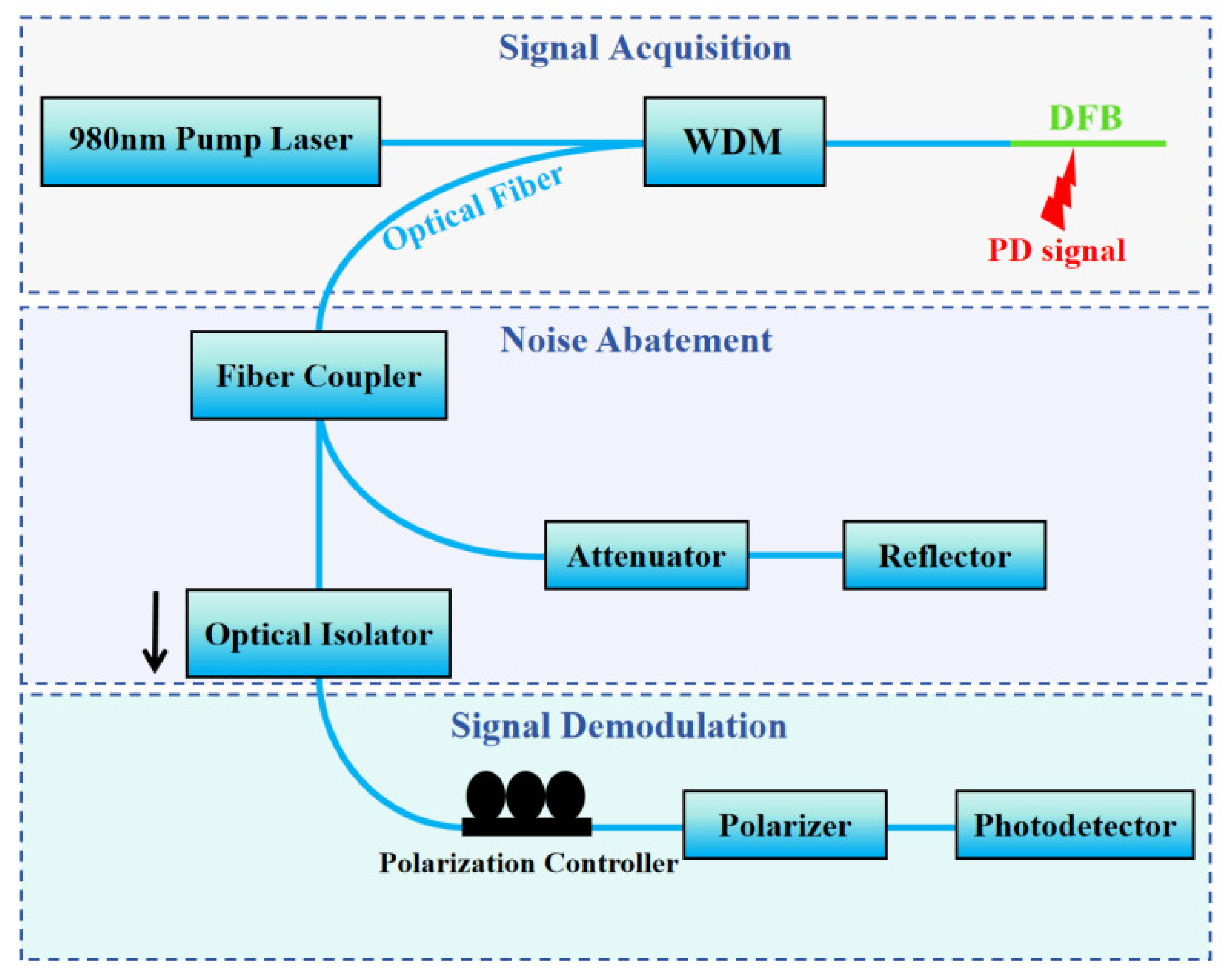

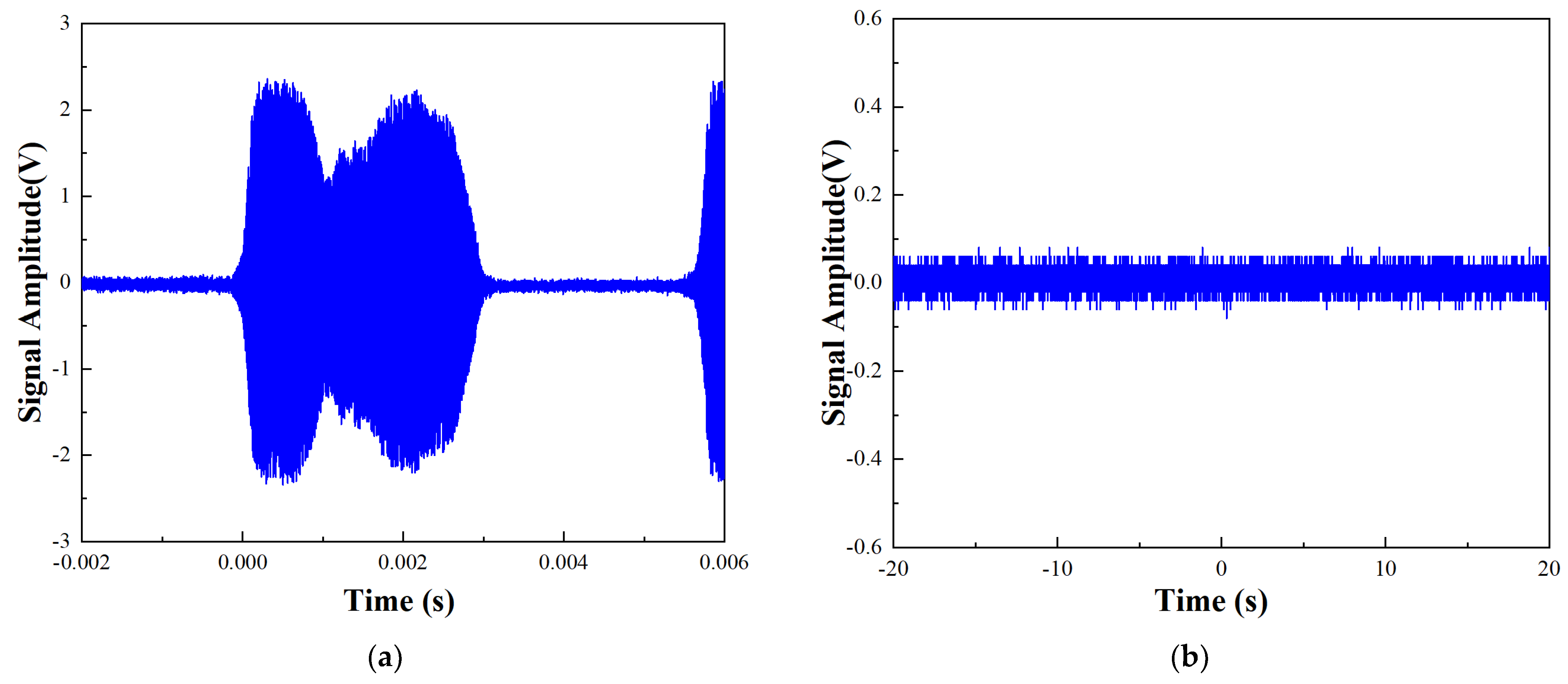

3. Active Feedback Optical Injection DFB Noise Suppression System

3.1. Feedback Optical Noise Mechanism

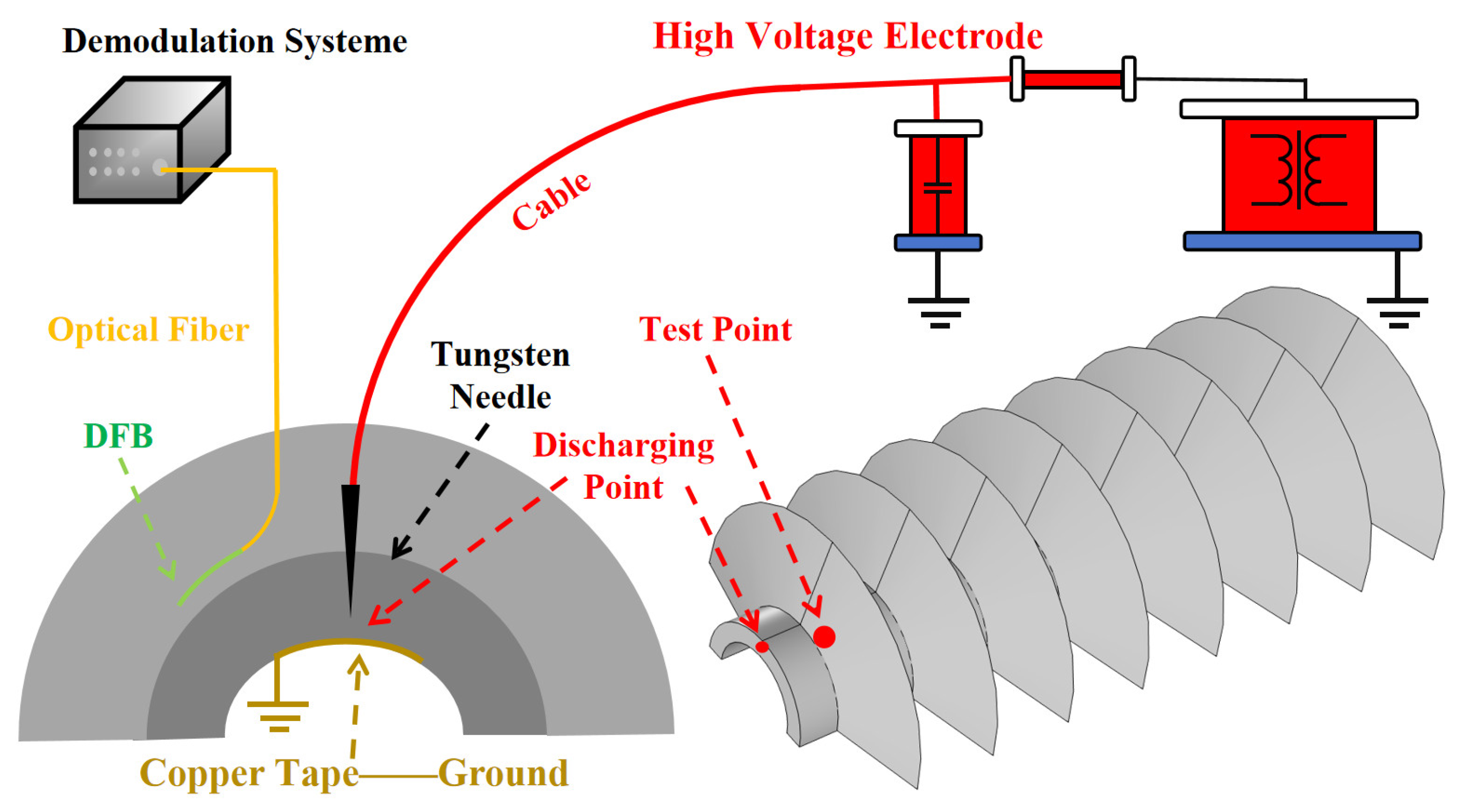

3.2. DFB Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection System

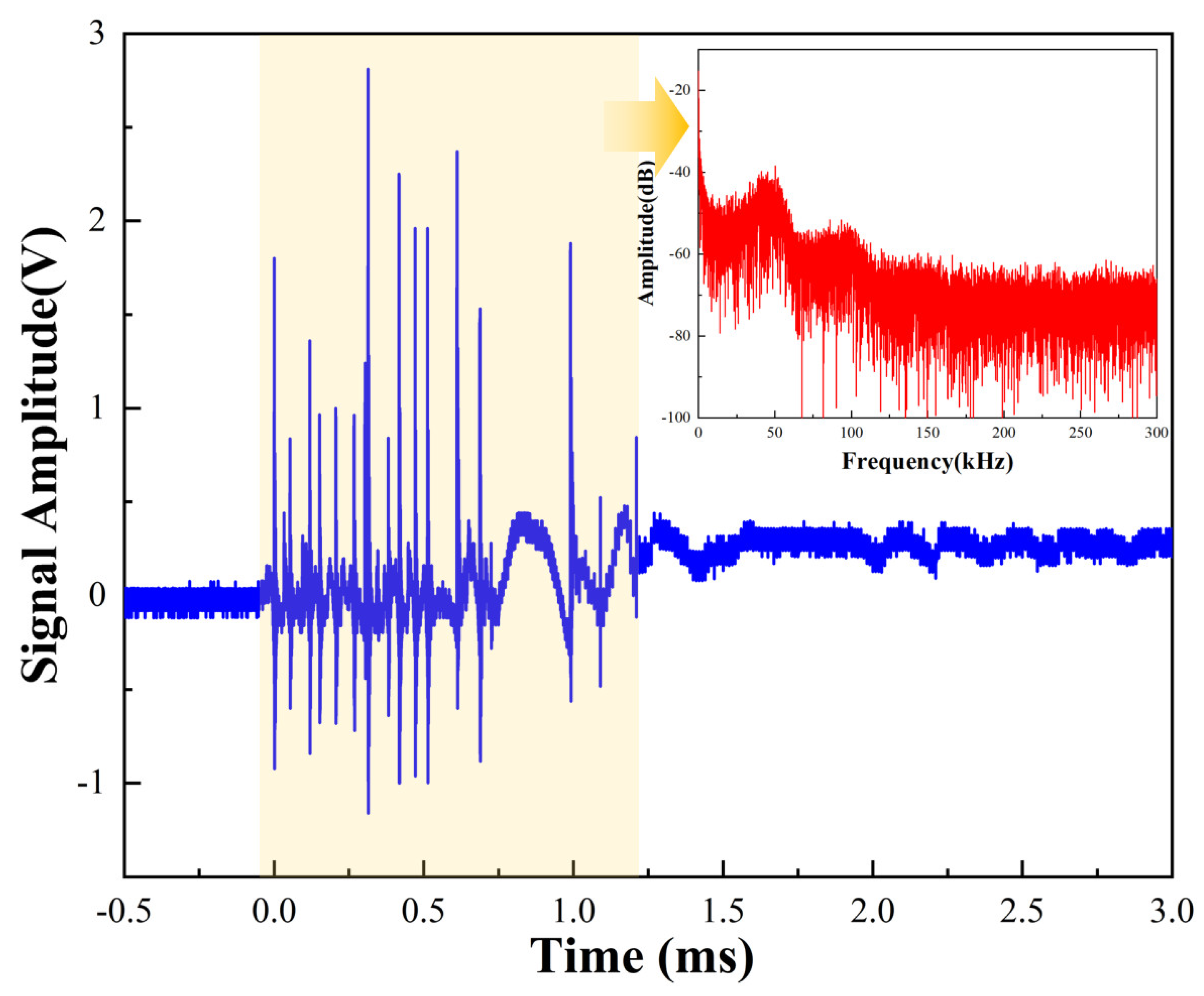

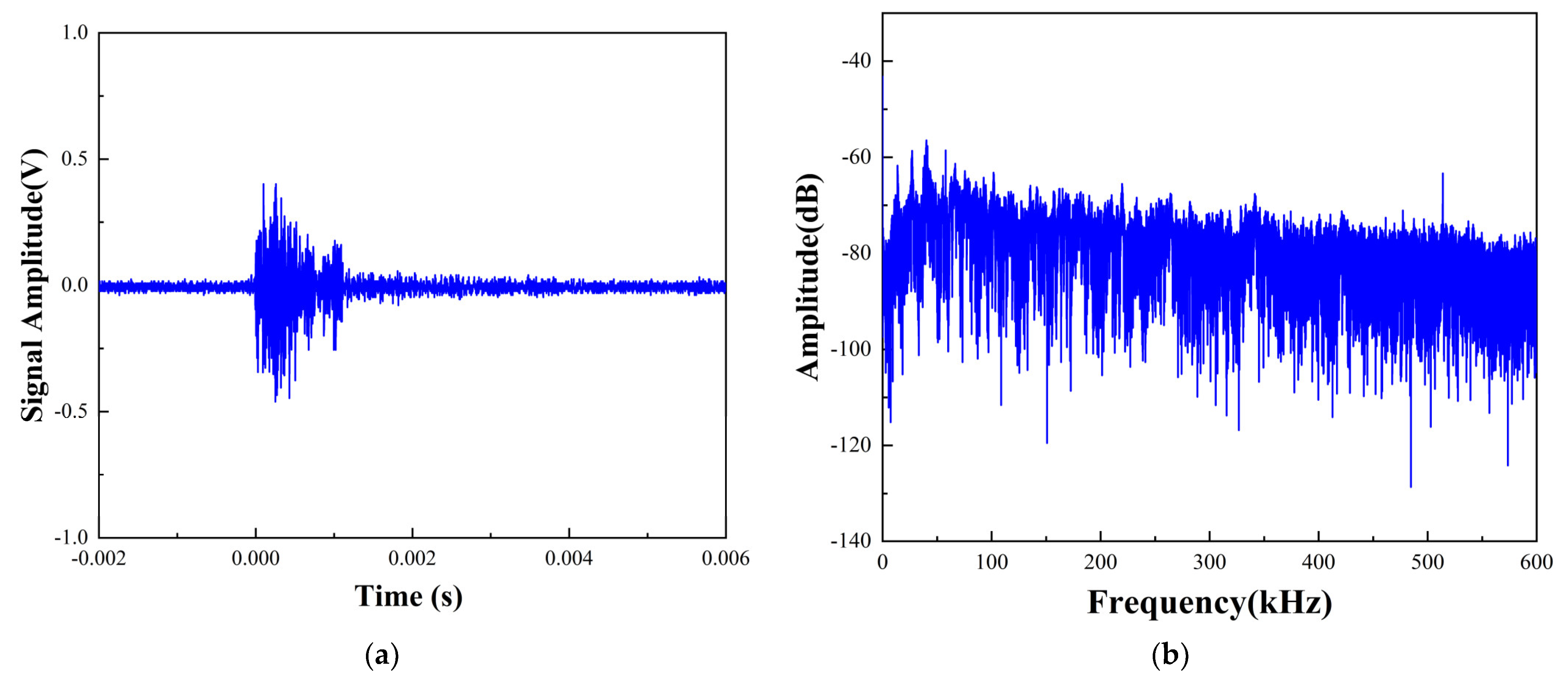

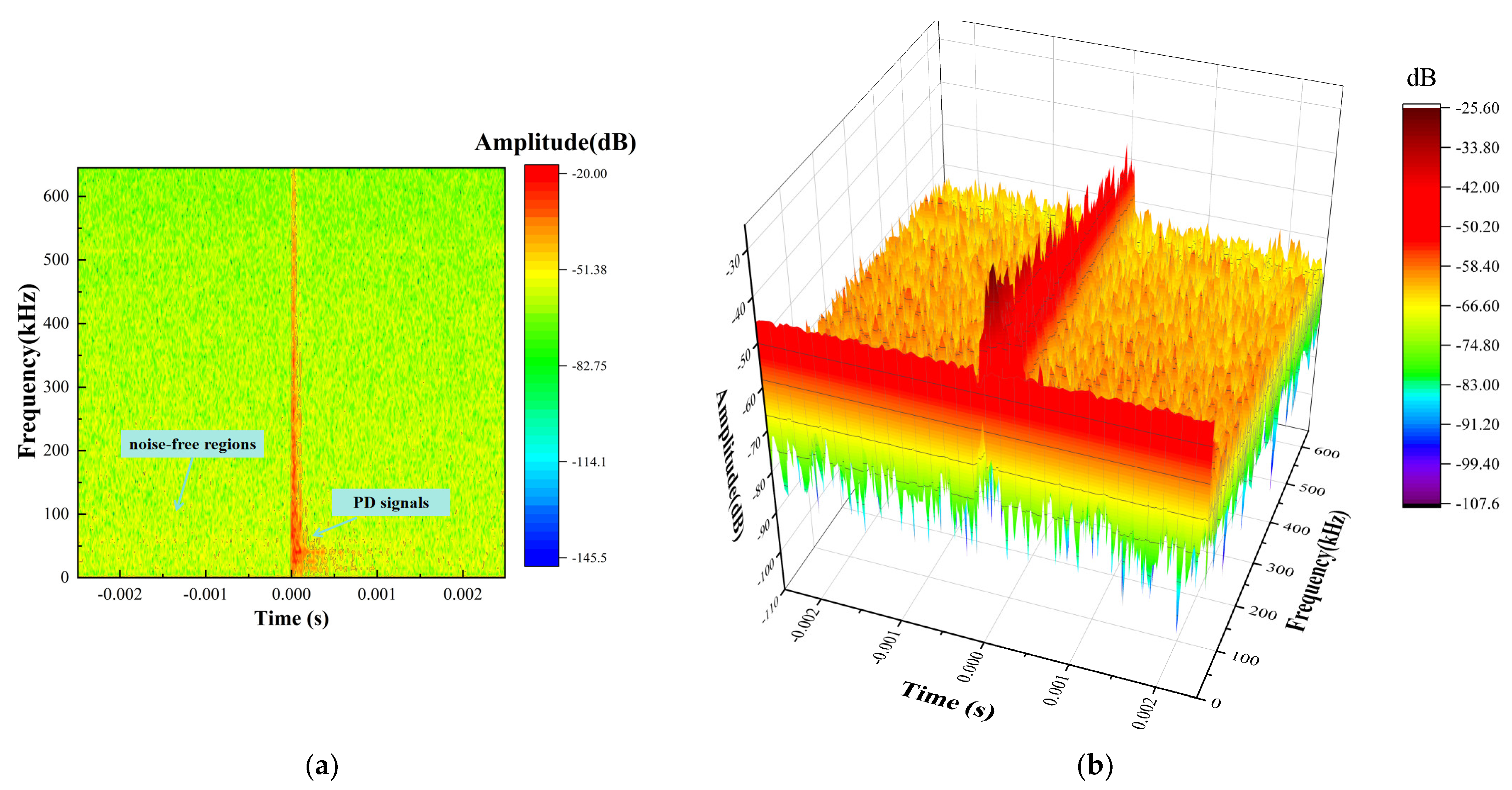

4. Partial Discharge Experimental Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaacob, M.M. Review on Partial Discharge Detection Techniques Related to High Voltage Power Equipment Using Different Sensors. Photonic Sens. 2014, 4, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, F.; Garnacho, F.; Ortego, J.; Sánchez-Urán, M.Á. Application of HFCT and UHF sensors in on-line partial discharge measurements for insulation diagnosis of high voltage equipment. Sensors 2015, 15, 7360–7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casals-Torrens, P.; González-Parada, A.; Bosch-Tous, R. Online PD detection on high voltage underground power cables by acoustic emission. Procedia Eng. 2012, 35, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitei, S.N.; Borah, K.; Chatterjee, S. Partial Discharge Detection in an Oil-Filled Power Transformer Using Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 10304–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-R.; Tsuda, H. A novel fiber Bragg grating acoustic emission sensor head for mechanical tests. Scr. Mater. 2005, 53, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Karalekas, D.; Botsis, J. On the effects of the lateral strains on the fiber Bragg grating response. Sensors 2013, 13, 2631–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Ma, G.; Mao, N.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, S. Ultrasonic detection coherence of fiber Bragg grating for partial discharge in transformers. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 19th International Conference on Dielectric Liquids (ICDL), Manchester, UK, 25–29 June 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorat, M.; Gharehpetian, G.B.; Latifi, H.; Hejazi, M.A.; Bagheri, M. High-resolution FBG-based fiber-optic sensor with temperature compensation for PD monitoring. Sensors 2019, 19, 5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lu, P.; Zhang, J.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Hu, P.; Yan, W.; Ni, W.; Liu, D.; et al. Micromachined extrinsic Fabry-Pérot cavity for low-frequency acoustic wave sensing. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 24300–24310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Huang, Y.Q.; Lei, W.; Ye, X.J. A Novel Fabry-Perot Cavity Fiber Sensor. Phys. Procedia 2012, 33, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qi, H.; Han, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Peng, W.; Chen, K. Ultrahigh-speed phase demodulation of a Fabry–Perot sensor based on fiber array parallel spectral detection. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lv, A.; Xie, Z.; Li, Y.; Yan, K. Impact analysis of fiber optic rings on partial discharge parameters. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 016037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Jin, B. Partial discharge ultrasound detection using the Sagnac interferometer system. Sensors 2018, 18, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.-Y.; Ma, G.-M.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.-C.; Li, C.-R. A High Sensitivity Optical Fiber Interferometer Sensor for Acoustic Emission Detection of Partial Discharge in Power Transformer. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Macalpine, M.; Demokan, M.S. The directionality of an optical fiber high-frequency acoustic sensor for partial discharge detection and location. J. Light. Technol. 2000, 18, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Mandal, S. Mathematical Modeling of π-Phase-Shifted Fiber Bragg Grating and its Application for Strain Measurement in Epoxy Resin Cantilever Beam. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 9856–9863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.M.; Zhou, H.Y.; Shi, C.; Li, Y.B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.R.; Zheng, Q. Distributed Partial Discharge Detection in a Power Transformer Based on Phase-Shifted FBG. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 2788–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H. DFB-FL Applied in the Liquid-Solid Composite Dielectric for Ultra-High Sensitive Partial Discharge Acoustic Emission Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 20960–20968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.C.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Q.C.; Shao, Q.B.; Qiao, J.X.; Zhao, H. Single Arm Optical Fiber Interferemeter Technology for Partial Discharge Acoustic Detection. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 3083–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Zhang, W.-C.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, H. The effect of polymer material properties on partial discharge vibration signals using EYDF-πPSG. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3527810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Improved demodulation method for fibre optic sensors applied in transformer partial discharge detection. High Volt. 2023, 8, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H. DFB Fiber Laser Based on External Optical Feedback Theory Applied in Long-Distance Power Transformer Partial Discharge Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 11747–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Q.; Cai, J.; Zhao, H. Ultra-High SNR Demodulation Method for Optical Fiber Sensors Applied in Power Transformer Partial Discharge Detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L.; Guan, B.O. Simultaneous strain and temperature fiber grating laser sensor based on radio-frequency measurement. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 20650–20656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, G.S.T.; Shao, L.Y.; Chan, H.L.W.; Tam, H.Y.; Hu, C.H.; Kim, H.H.; Liu, R.; Shung, K.K. Characterization of a 40-MHz focused transducer with a fiber grating laser hydrophone. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2009, 55, 2714–2718. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Wong, A.C.L.; Liu, W.; Guan, B.O.; Lu, C.; Tam, H.Y. Beat-frequency adjustable Er-doped DBR fiber laser for ultrasound detection. Opt. Exp. 2011, 19, 2485–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liang, Y.; Jin, L.; Sun, H.; Cheng, L.; Guan, B.O. Highly sensitive fiber laser ultrasound hydrophones for sensing and imaging applications. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 4530–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Liu, Y. DFB fiber laser hydrophone with bandpass response. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 4320–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.K.W.; Garside, B.K. Characterization of single-mode optical fiber filters. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, G.A.; Glenn, W.H. Design of a single-mode linear-cavity erbium fiber laser utilizing Bragg reflectors. J. Light. Technol. 1992, 10, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, B.-O.; Tam, H. Distributed bragg-reflector fiber-laser sensor for lateral force measurement. In Proceedings of the 2007 Asia Optical Fiber Communication and Optoelectronics Conference, Shanghai, China, 17–19 October 2007; pp. 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, B.-O.; Sun, X.-S.; Tan, Y.-N. Dual polarization fiber grating laser accelerometer. In Proceedings of the (EWOFS’10) Fourth European Workshop on Optical Fibre Sensors, Porto, Portugal, 8–10 September 2010; Santos, J.L., Culshaw, B., López-Higuera, J.M., MacPherson, W.N., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; p. 76530Z. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.L.W.; Chiang, K.S.; Price, D.C.; Gardner, J.L. The characterization of high-frequency ultrasonic fields using a polarimetric optical fiber sensor. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 66, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C. Theory of the linewidth of semiconductor lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1982, 18, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acket, G.; Lenstra, D.; Den Boef, A.; Verbeek, B. The influence of feedback intensity on longitudinal mode properties and optical noise in index-guided semiconductor lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1984, 20, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Hou, J.; Chen, L.; Tang, L.; Xu, M. Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection of Low-Intensity Noise Fiber Laser Based on Polarized Light Demodulation. Energies 2025, 18, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040955

Zhang Z, Liang Z, Hou J, Chen L, Tang L, Xu M. Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection of Low-Intensity Noise Fiber Laser Based on Polarized Light Demodulation. Energies. 2025; 18(4):955. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040955

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhenpeng, Zhengbo Liang, Junping Hou, Li Chen, Lin Tang, and Mingzhong Xu. 2025. "Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection of Low-Intensity Noise Fiber Laser Based on Polarized Light Demodulation" Energies 18, no. 4: 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040955

APA StyleZhang, Z., Liang, Z., Hou, J., Chen, L., Tang, L., & Xu, M. (2025). Solid Insulation Partial Discharge Detection of Low-Intensity Noise Fiber Laser Based on Polarized Light Demodulation. Energies, 18(4), 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040955