Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Acoustic Sensing

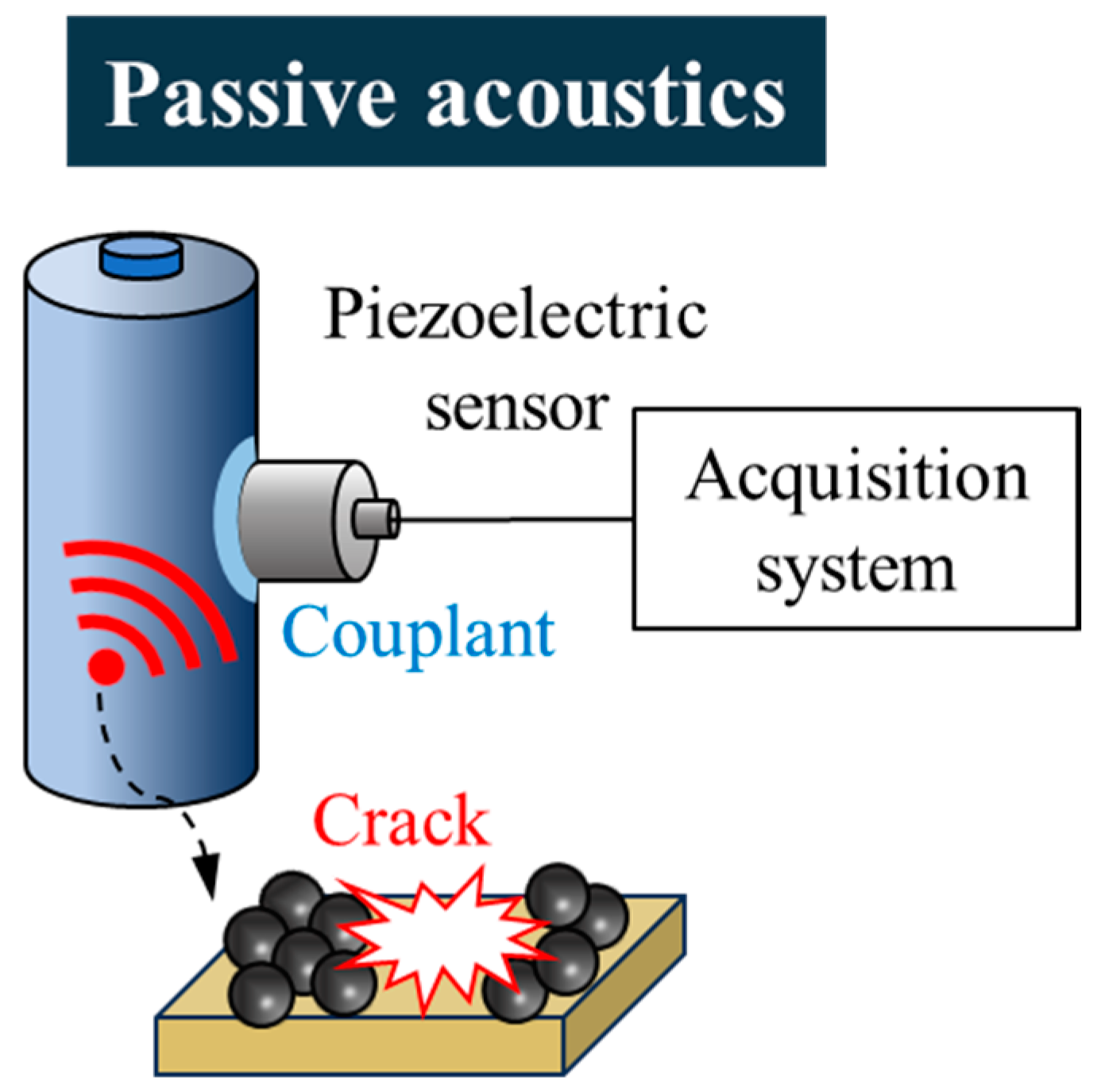

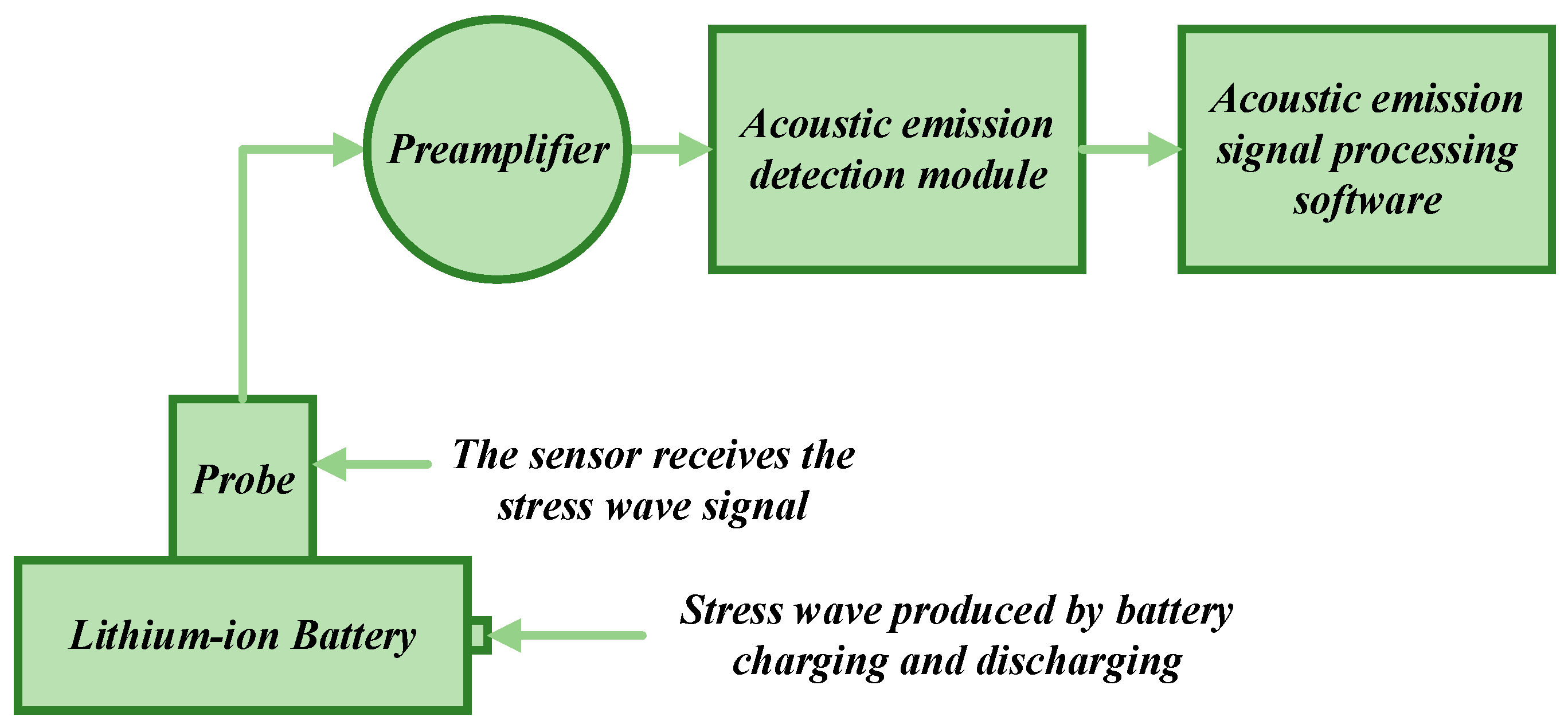

2.1. Acoustic Emission Technology

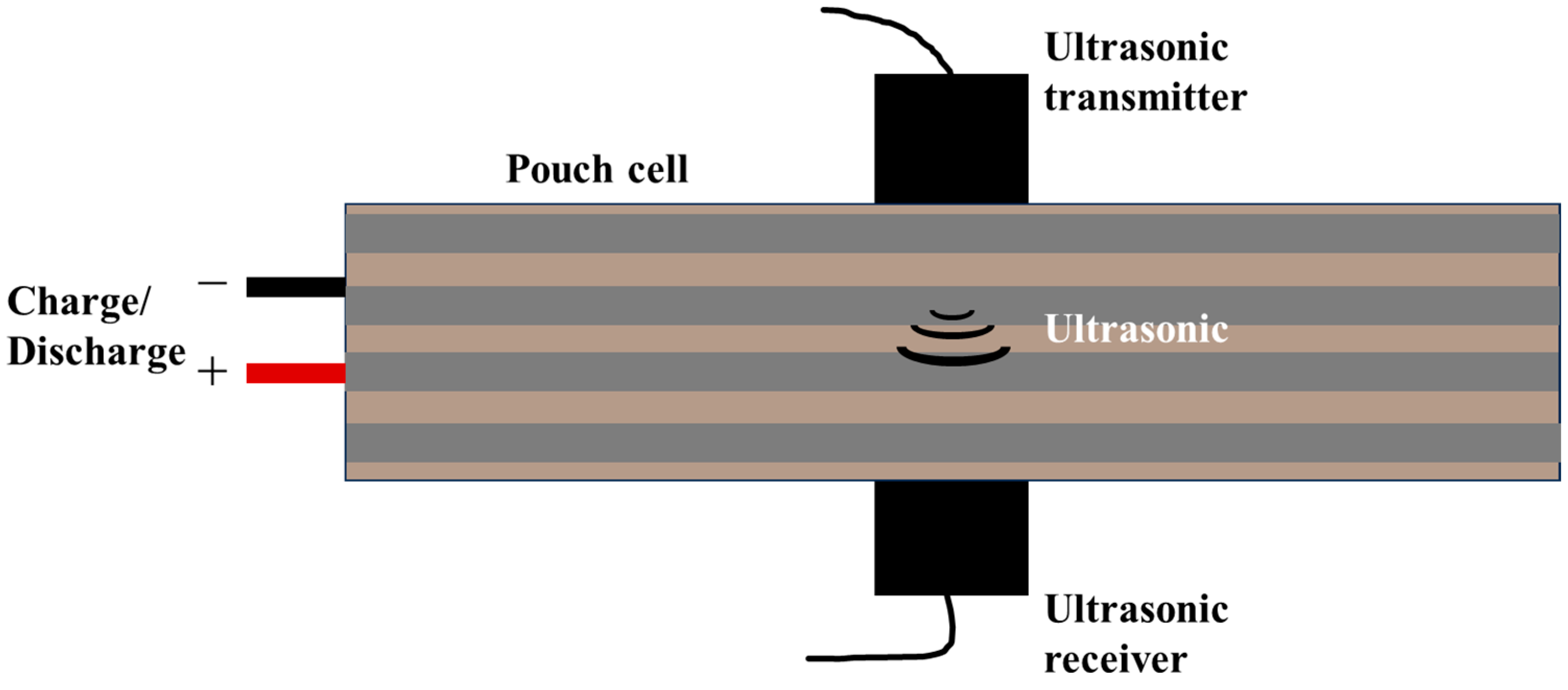

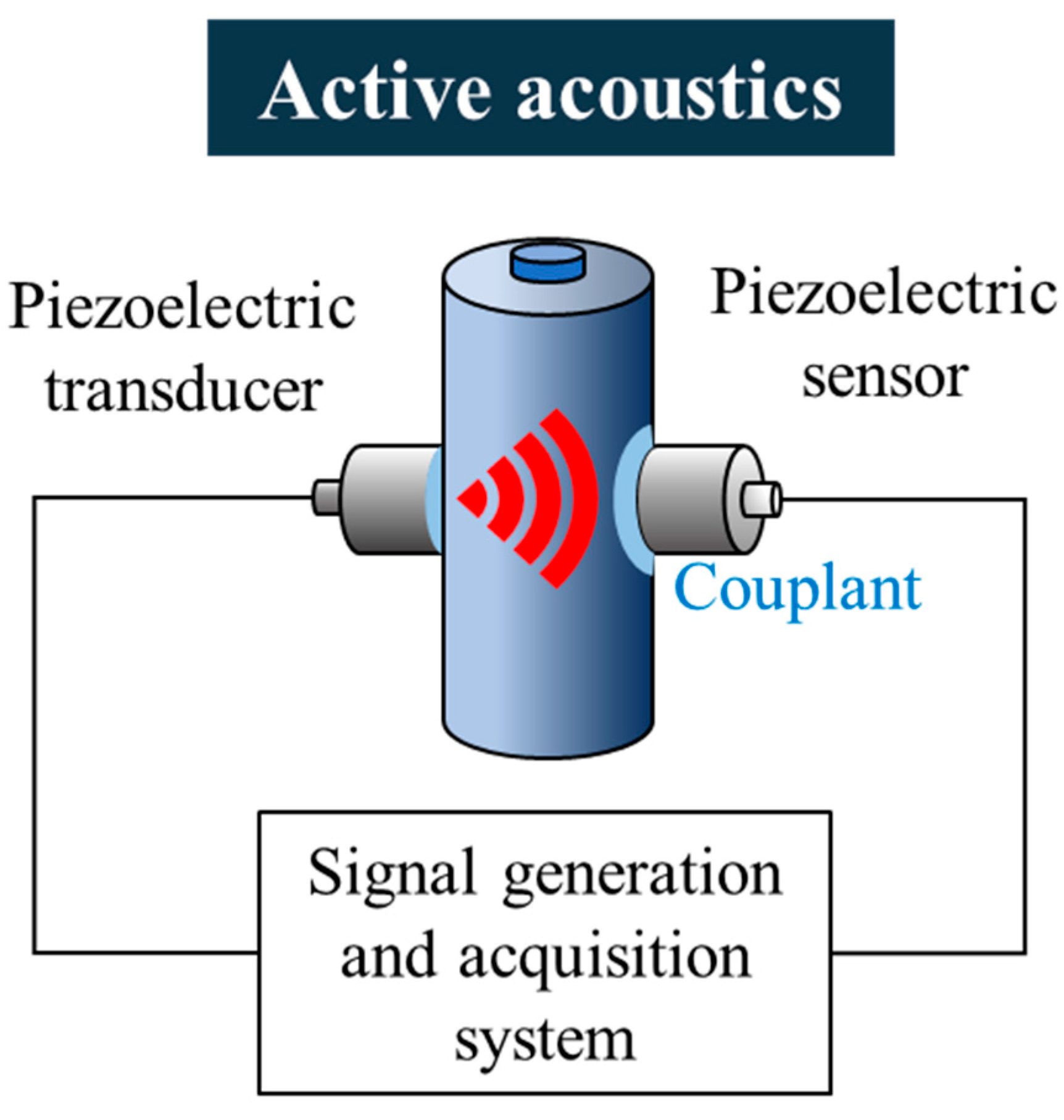

2.2. Ultrasonic Testing Technology

3. LIB-Based Acoustic Sensing Technology

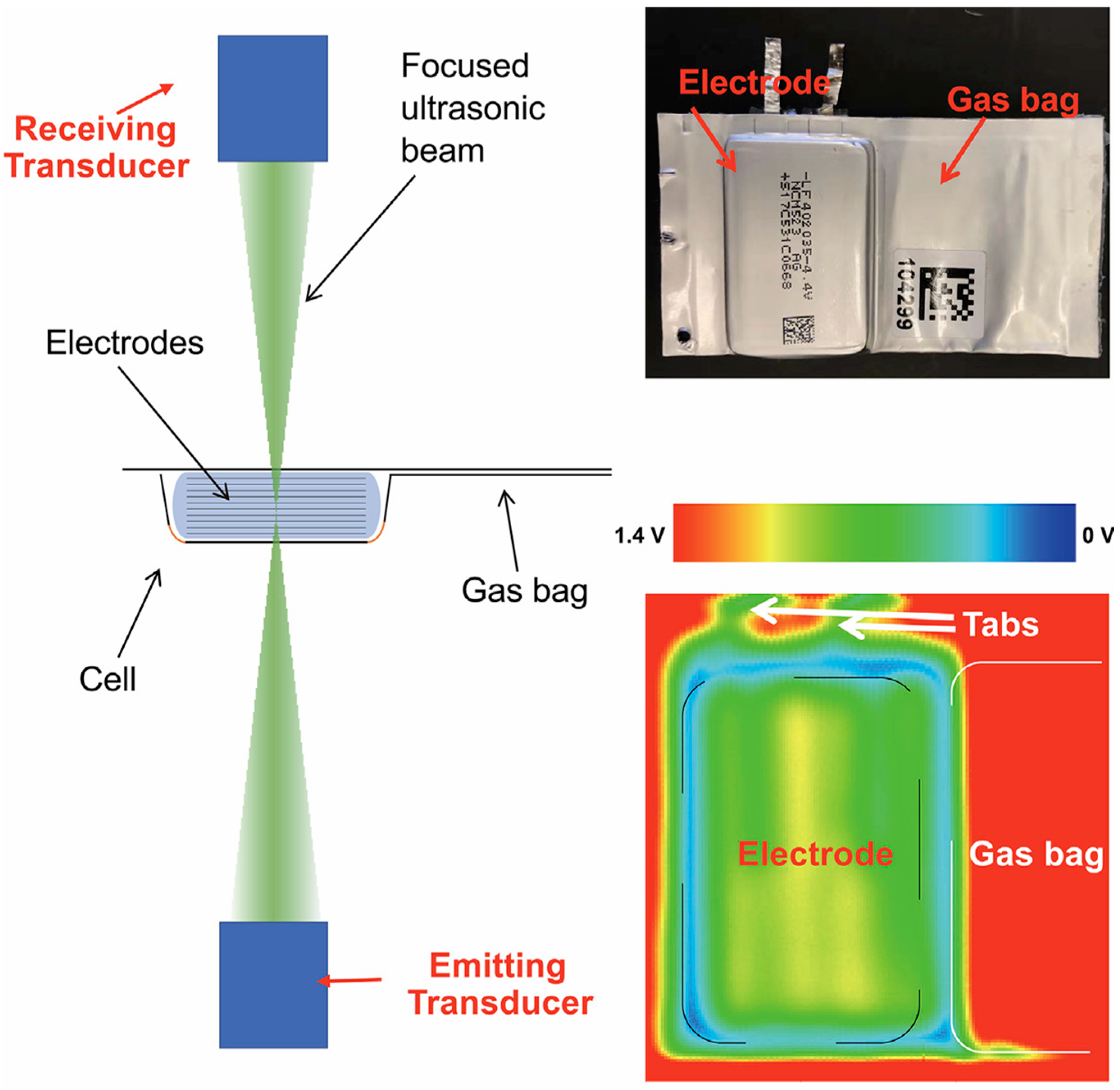

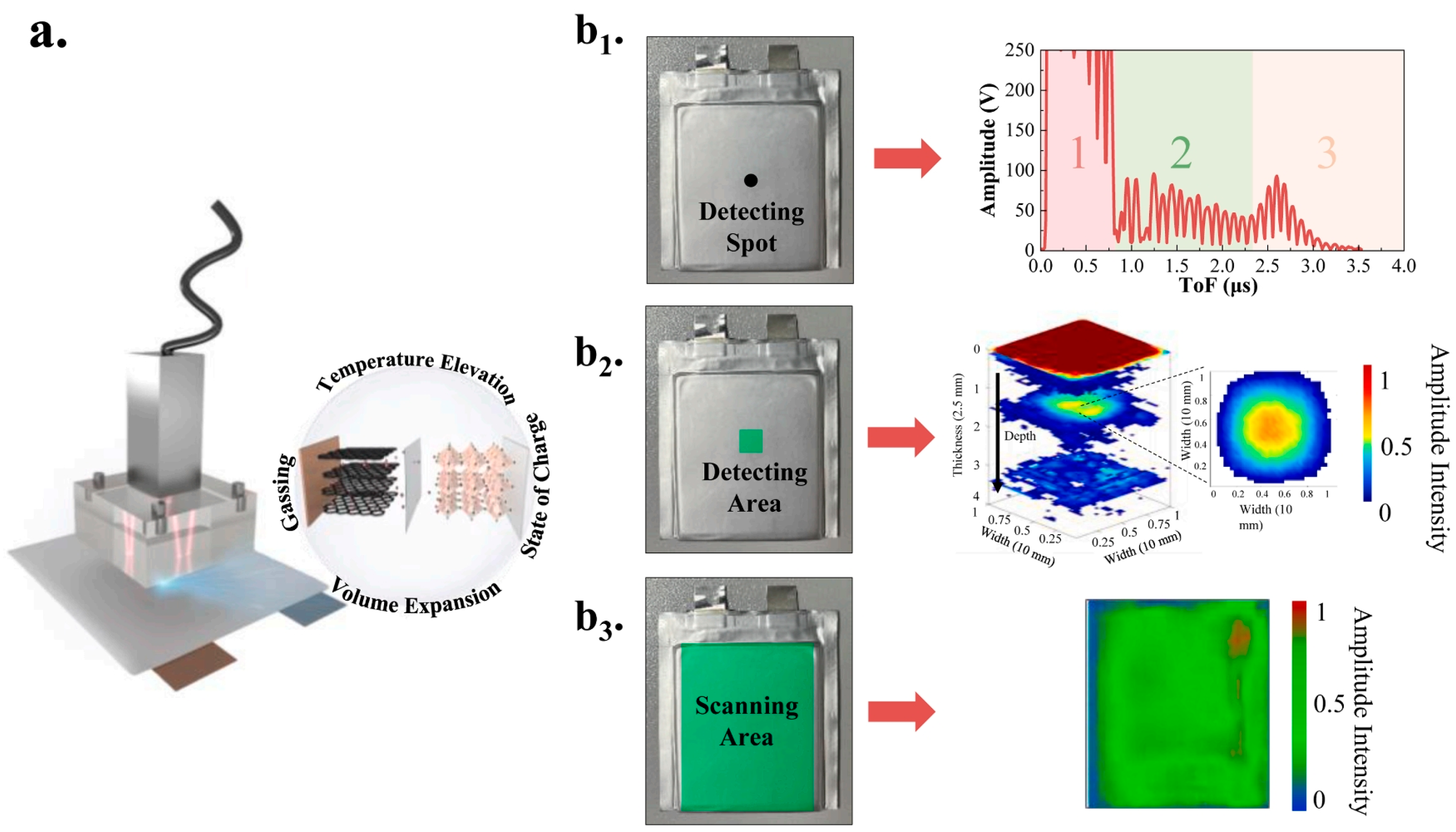

3.1. The Application of Ultrasonic Testing Technology in the Field of Battery Inspection

3.1.1. Ultrasonic Testing of SOC

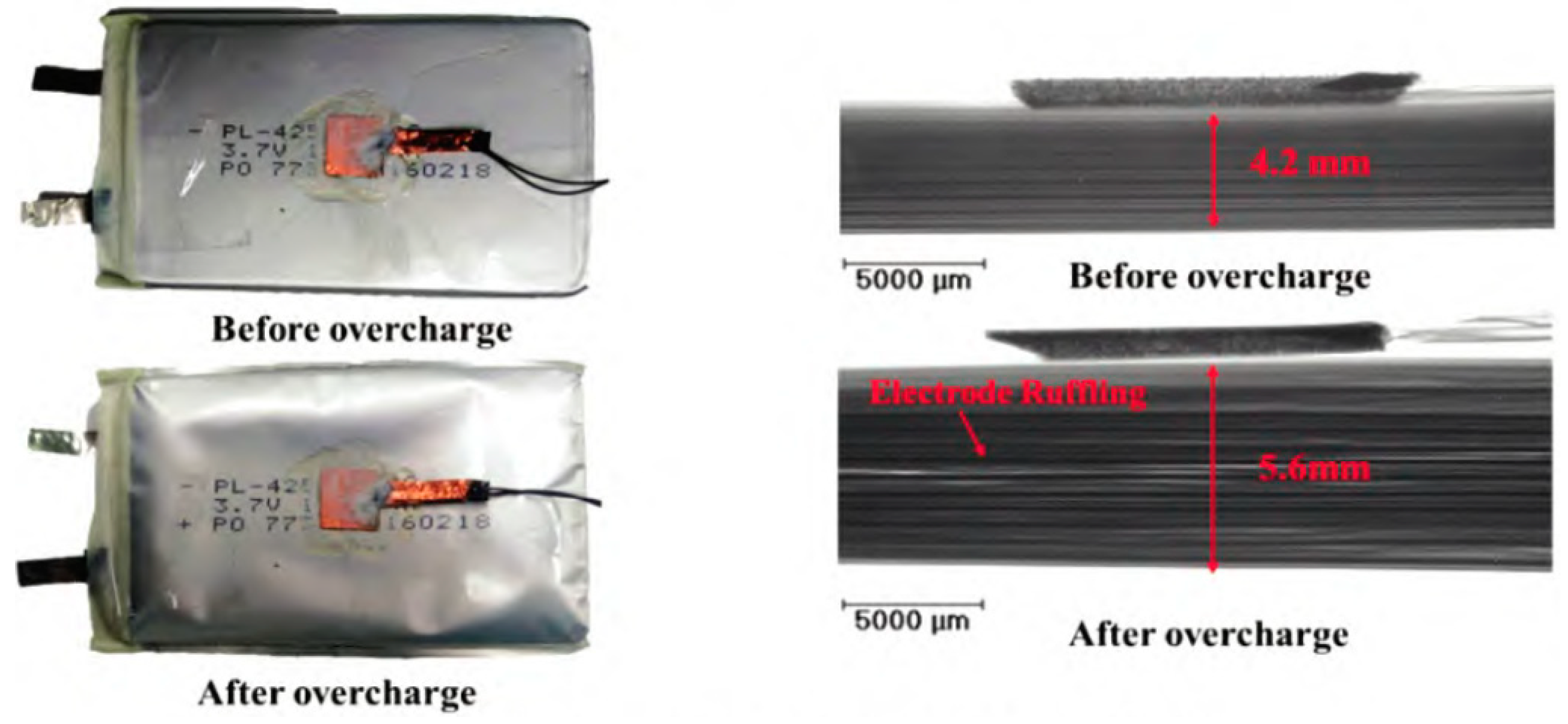

3.1.2. Ultrasonic Testing of Overcharge Behavior

3.1.3. SOH Estimation Based on Ultrasonic Testing

3.1.4. In Situ Detection

3.2. Application of Acoustic Emission Technology in the Field of Battery Testing

3.2.1. Acoustic Emission Detection for SOH

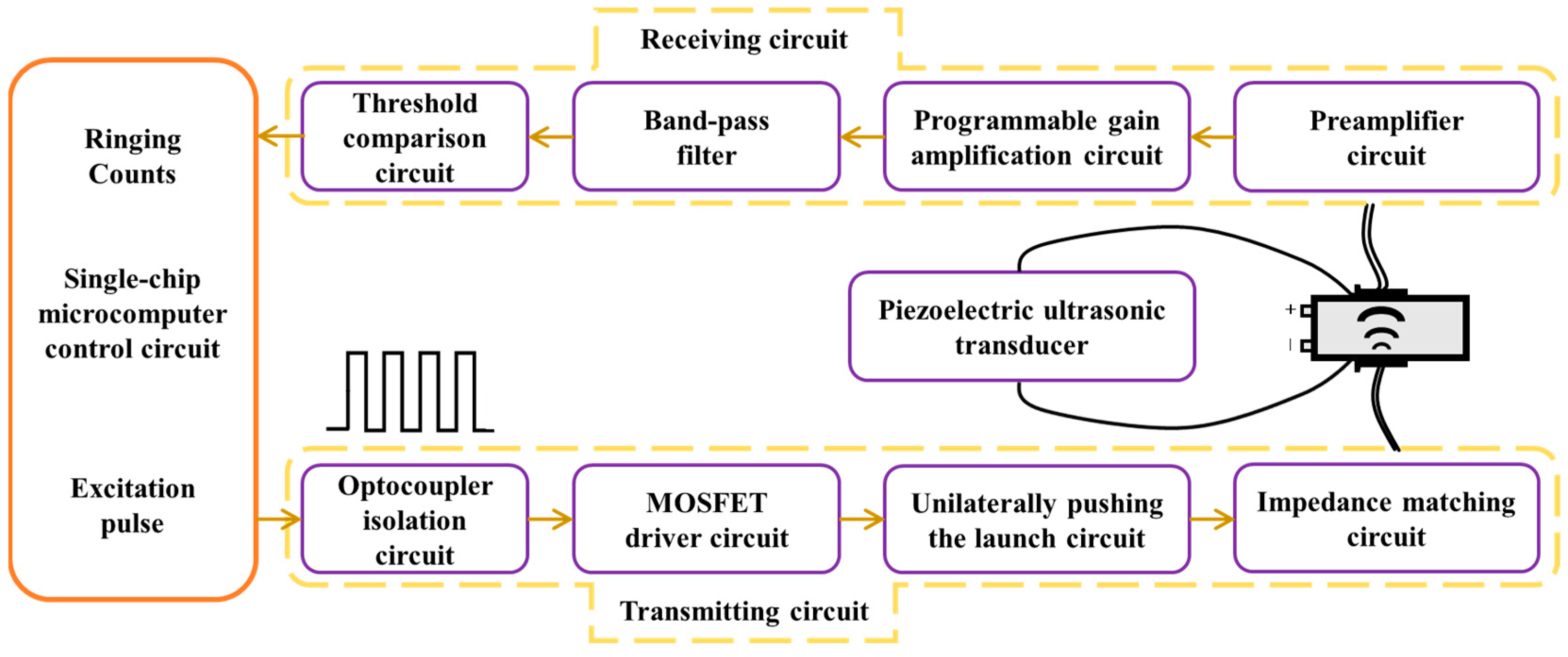

3.2.2. Active Acoustic Emission Sensing for Fast Co-Estimation of SOC and SOH

- (1)

- Fundamental frequency f0: Generated by the excitation frequency.

- (2)

- Harmonics of the fundamental frequency nf0 (where n denotes a positive integer): they are caused by the transducer itself or possibly by nonlinear propagation in the cell.

- (3)

- Elementary f0/n subharmonics: they are excited by bubbles twice the size of the resonance or non-spherical bubbles with surface oscillations.

4. Results and Discussion

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuanyuan, P.; Yifan, Z.; Yanan, L.; Haosong, L.; Yao, C.; Qiang, L.; Mingbo, W. Homonuclear transition-metal dimers embedded monolayer C2N as promising anchoring and electrocatalytic materials for lithium-sulfur battery: First-principles calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 610, 155507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Cui, S.; Chen, M.; Zhou, S.; Wang, K. Review of Family-Level Short-Term Load Forecasting and Its Application in Household Energy Management System. Energies 2023, 16, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Jingyi, G.; Le, K.; Yi, Z.; Licheng, W.; Kai, W. State of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on modified flower pollination algorithm-temporal convolutional network. Energy 2023, 283, 128742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tang, Y.; Ren, J.; Wei, Y. State of charge estimation with the adaptive unscented Kalman filter based on an accurate equivalent circuit model. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, K. A Novel Approach for State of Health Estimation and Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Supercapacitors Using an Improved Honey Badger Algorithm Assisted Hybrid Neural Network. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, T.; Wang, K. A comprehensive review on research methods for lithium-ion battery of state of health estimation and end of life prediction: Methods, properties, and prospects. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lv, X.; Wang, K. Application of triboelectric nanogenerator in self-powered motion detection devices: A review. APL Mater. 2024, 12, 070601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yuan, L.; Xu, H.; Huang, Y. Building Practical High-Voltage Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries (Adv. Mater. 52/2022). Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2270362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namhyung, K.; Yujin, K.; Jaekyung, S.; Jaephil, C. Issues impeding the commercialization of laboratory innovations for energy-dense Si-containing lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Yang, L.; Yuan, L.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, J.; Pan, F.; Huang, Y.J.J. Alkali-metal anodes: From lab to market. Joule 2019, 3, 2334–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Du, G.; Wang, K. Progress in estimating the state of health using transfer learning–based electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of lithium-ion batteries. Ionics 2025, 1–13, prepublish. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, M.S. Electrical energy storage and intercalation chemistry. Science 1976, 192, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, K.; Jones, P.; Wiseman, P.; Goodenough, J.B. LixCoO2 (0 < x < −1): A new cathode material for batteries of high energy density. Mater. Res. Bull. 1980, 15, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhou, J.; Ullah, S.; Yang, X.; Tokarska, K.; Trzebicka, B.; Ta, H.Q.; Rümmeli, M.H. A review of recent developments in Si/C composite materials for Li-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 34, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaosen, T.; Guobo, Z.; Ann, R.; Tan, S.; Haegyeom, K.; Jingyang, W.; Julius, K.; Yingzhi, S.; Bin, O.; Tina, C.; et al. Promises and Challenges of Next-Generation “Beyond Li-ion” Batteries for Electric Vehicles and Grid Decarbonization. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 1623–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, J. Key Challenges for grid-scale lithium-ion battery energy storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2202197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, W.; Liwei, L.; Yong, L.; Peng, D.; Guoting, X. Application Research of Chaotic Carrier Frequency Modulation Technology in Two-Stage Matrix Converter. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 2614327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, K. Research Progress and Prospects of Liquid–Liquid Triboelectric Nanogenerators: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Challenges. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanli, W.; Dongfang, Y.; Zhenxing, H.; Han, H.; Licheng, W.; Kai, W. Electrodeless Nanogenerator for Dust Recover. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2200699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, W.; Liwei, L.; Huaixian, Y.; Tiezhu, Z.; Wubo, W. Thermal Modelling Analysis of Spiral Wound Supercapacitor under Constant-Current Cycling. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Tang, X.; Dai, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Wei, X.; Huang, Y.J.E.E.R. Building safe lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: A review. Energy Rev. 2020, 3, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Zhang, M.; Fu, Y.; Wang, K. Transfer learning to estimate lithium-ion battery state of health with electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Energy Storage 2025, 110, 115345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominko, R.; Fichtner, M.; Otuszewski, T. Battery 2030+. Available online: https://battery2030.eu/research/roadmap/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Xin, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, L.; Song, W.; Sun, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, D. Implantable Sensing Technology for Lithium-ion Batteries. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Qiu, J.; Ming, H.; Fang, Z. Analysis of nondestructive testing and monitoring methods for batteries. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 1713–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Ge, X.; Sun, Q.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y. Health monitoring by optical fiber sensing technology for rechargeable batteries. eScience 2024, 4, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Boles, S.T.; Tarascon, J.-M.J.N.S. Sensing as the key to battery lifetime and sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y. Progress on acoustic and optical sensing technologies for lithium rechargeable batteries. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majasan, J.O.; Robinson, J.B.; Owen, R.E.; Maier, M.; Radhakrishnan, A.N.; Pham, M.; Tranter, T.G.; Zhang, Y.; Shearing, P.R.; Brett, D.J. Recent advances in acoustic diagnostics for electrochemical power systems. J. Phys. Energy 2021, 3, 032011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohzuku, T.; Tomura, H.; Sawai, K. Monitoring of particle fracture by acoustic emission during charge and discharge of Li/MnO2 cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier-Laurent, S.; Idrissi, H.; Roué, L. In-situ study of the cracking of metal hydride electrodes by acoustic emission technique. J. Power Sources 2008, 179, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, C.; Redfern, B. Acoustic emission studies of the breakdown of beta-alumina under conditions of sodium ion transport. J. Mater. Sci. 1978, 13, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohzuku, T.; Matoba, N.; Sawai, K. Direct evidence on anomalous expansion of graphite-negative electrodes on first charge by dilatometry. J. Power Sources 2001, 97, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.; Dudney, N.; Lara-Curzio, E.; Daniel, C. Understanding the degradation of silicon electrodes for lithium-ion batteries using acoustic emission. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, C.-Y.; Jung, W.-S.; Byeon, J.-W. Damage evaluation in lithium cobalt oxide/carbon electrodes of secondary battery by acoustic emission monitoring. Mater. Trans. 2015, 56, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweidler, S.; Bianchini, M.; Hartmann, P.; Brezesinski, T.; Janek, J. The sound of batteries: An operando acoustic emission study of the LiNiO2 cathode in Li–ion cells. Batter. Supercaps 2020, 3, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Muralidharan, N.; Amin, R.; Rathod, V.; Ramuhalli, P.; Belharouak, I. Ultrasonic nondestructive diagnosis of lithium-ion batteries with multiple frequencies. J. Power Sources 2022, 549, 232091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y. Application of Ultrasonic Technology in Characterization of Lithium-ion Batteries. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 1033–1039. Available online: https://esst.cip.com.cn/CN/10.12028/j.issn.2095-4239.2019.0146 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Robinson, J.B.; Owen, R.E.; Kok, M.D.; Maier, M.; Majasan, J.; Braglia, M.; Stocker, R.; Amietszajew, T.; Roberts, A.J.; Bhagat, R. Identifying defects in Li-ion cells using ultrasound acoustic measurements. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 120530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, B.; Hendricks, C.; Osterman, M.; Pecht, M. Health monitoring of lithium-ion batteries. EDFA Tech. Artic. 2014, 16, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ding, H.; Luscombe, A.; Johnson, M.; Harlow, J.E.; Gauthier, R.; Dahn, J.R. Ultrasonic scanning to observe wetting and “unwetting” in Li-ion pouch cells. Joule 2020, 4, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Rao, Z.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Fang, C.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xie, X.; Huang, Y. Lithium-Metal Batteries: Polycationic Polymer Layer for Air-Stable and Dendrite-Free Li Metal Anodes in Carbonate Electrolytes (Adv. Mater. 12/2021). Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2170087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, K.; Du, J.; Han, Y.; Shen, Y. Ultrasonic Appearance of Trace Water Pollution in Electrolyte of Lithium-ion Battery. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 4030–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; Huang, K.; Luo, W.; Meng, J.; Zhou, L.; Deng, Z.; Wen, J.; Dai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Shen, Y. Evaluating interfacial stability in solid-state pouch cells via ultrasonic imaging. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.; Bhadra, S.; Hertzberg, B.; Gjeltema, P.; Goy, A.; Fleischer, J.W.; Steingart, D.A. Electrochemical-acoustic time of flight: In operando correlation of physical dynamics with battery charge and health. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louli, A.; Eldesoky, A.; Weber, R.; Genovese, M.; Coon, M.; Degooyer, J.; Deng, Z.; White, R.; Lee, J.; Rodgers, T. Diagnosing and correcting anode-free cell failure via electrolyte and morphological analysis. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.B.; Maier, M.; Alster, G.; Compton, T.; Brett, D.J.; Shearing, P.R. Spatially resolved ultrasound diagnostics of Li-ion battery electrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 6354–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, L.; Bach, T.; Virsik, W.; Schmitt, A.; Müller, J.; Staab, T.E.; Sextl, G. Probing lithium-ion batteries’ state-of-charge using ultrasonic transmission–Concept and laboratory testing. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Knehr, K.W.; Van Tassell, B.; Hodson, T.; Biswas, S.; Hsieh, A.G.; Steingart, D.A. State of charge and state of health estimation using electrochemical acoustic time of flight analysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladpli, P.; Kopsaftopoulos, F.; Chang, F.-K. Estimating state of charge and health of lithium-ion batteries with guided waves using built-in piezoelectric sensors/actuators. J. Power Sources 2018, 384, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Z.; Kubiak, P. Lithium-ion battery SOC/SOH adaptive estimation via simplified single particle model. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 12444–12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, G.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A. A review on online state of charge and state of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 5141–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Guided wave based structural health monitoring: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2016, 25, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hua, W.; Wu, C.; Zheng, S.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J. State estimation of a lithium-ion battery based on multi-feature indicators of ultrasonic guided waves. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, C.; Fu, C.; Zheng, S.; Tian, J. State characterization of lithium-ion battery based on ultrasonic guided wave scanning. Energies 2022, 15, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Tian, J.; Tian, Y. State-of-charge estimation tolerant of battery aging based on a physics-based model and an adaptive cubature Kalman filter. Energy 2021, 220, 119767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Huang, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, X. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on cubature Kalman filters with different matrix decomposition strategies. Energy 2022, 238, 121917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, S.; Luo, Y.; Xu, B.; Hao, W. Guided wave imaging of thin lithium-ion pouch cell using scanning laser Doppler vibrometer. Ionics 2021, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Jiang, S.; Hao, W. State-of-charge and state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion battery using the direct wave signals of guided wave. J. Energy Storage 2021, 39, 102657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Sun, C.; Yang, S.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J. State of charge and temperature joint estimation based on ultrasonic reflection waves for lithium-ion battery applications. Batteries 2023, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, Z.; Huang, K.; Xu, M.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Y. Precise state-of-charge mapping via deep learning on ultrasonic transmission signals for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 8217–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, H.; Koller, M.; Keller, S.; Glanz, G.; Klambauer, R.; Bergmann, A. State estimation approach of lithium-ion batteries by simplified ultrasonic time-of-flight measurement. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 170992–171000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchev, A.; Guillet, N.; Brun-Buission, D.; Gau, V. Li-ion cell safety monitoring using mechanical parameters: Part, I. Normal battery operation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 010515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladpli, P.; Liu, C.; Kopsaftopoulos, F.; Chang, F.-K. Estimating lithium-ion battery state of charge and health with ultrasonic guided waves using an efficient matching pursuit technique. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific), Bangkok, Thailand, 6–9 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, T.; Lieske, U.; Nikolowski, K.; Marcinkowski, P.; Wolter, M.; Schubert, L. Monitoring of lithium-ion cells with elastic guided waves. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Palermo, Italy, 5–8 July 2020; Special Collection of 2020 Papers. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, B.; Jin, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Q. State-of-charge characterization of lithium-ion batteries based on sonic time-domain characteristics. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2021, 36, 4666–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Chang, W.; Xu, J. A robust ultrasonic characterization methodology for lithium-ion batteries on frequency-domain damping analysis. J. Power Sources 2022, 547, 232003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, G.; Liangheng, Z.; Yan, L.; Fan, S.; Bin, W.; Cunfu, H. Ultrasonic guided wave measurement and modeling analysis of the state of charge for lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xue, J.; Ma, L. Research on Cyclic Aging of Typical Energy Storage Conditions of Lithium Iron Phosphate Battery Packs. Chin. J. Power Sources 2022, 46, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Ren, D.; Lu, L.; Li, J.; Feng, X.; Han, X.; Liu, G. Overcharge-induced capacity fading analysis for large format lithium-ion batteries with LiyNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2+ LiyMn2O4 composite cathode. J. Power Sources 2015, 279, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Hua, W.; Yang, X.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J.; Xiong, R. Optimal charging for lithium-ion batteries to avoid lithium plating based on ultrasound-assisted diagnosis and model predictive control. Appl. Energy 2024, 367, 123396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, S.K.; Kim, J.; Lucht, B.L. Generation and Evolution of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 2322–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oca, L.; Guillet, N.; Tessard, R.; Iraola, U. Lithium-ion capacitor safety assessment under electrical abuse tests based on ultrasound characterization and cell opening. J Energy Storage 2019, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yung, W.K.; Pecht, M. Ultrasonic health monitoring of lithium-ion batteries. Electronics 2019, 8, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, R.; Cumming, D.; Wu, Y.; Dwyer-Joyce, R. Measurements and modelling of the response of an ultrasonic pulse to a lithium-ion battery as a precursor for state of charge estimation. J. Energy Storage 2021, 36, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Q. A systematic investigation of internal physical and chemical changes of lithium-ion batteries during overcharge. J. Power Sources 2022, 518, 230767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z. Research on Real-time Detection Method of Overcharge of Lithium-ion Battery Based on Ultrasonic Time Domain Characteristics. Chin. J. Power Sources 2023, 47, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.B.; Pham, M.; Kok, M.D.; Heenan, T.M.; Brett, D.J.; Shearing, P.R. Examining the cycling behaviour of li-ion batteries using ultrasonic time-of-flight measurements. J. Power Sources 2019, 444, 227318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xiong, R.; Shen, W. A review on state of health estimation for lithium ion batteries in photovoltaic systems. ETransportation 2019, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

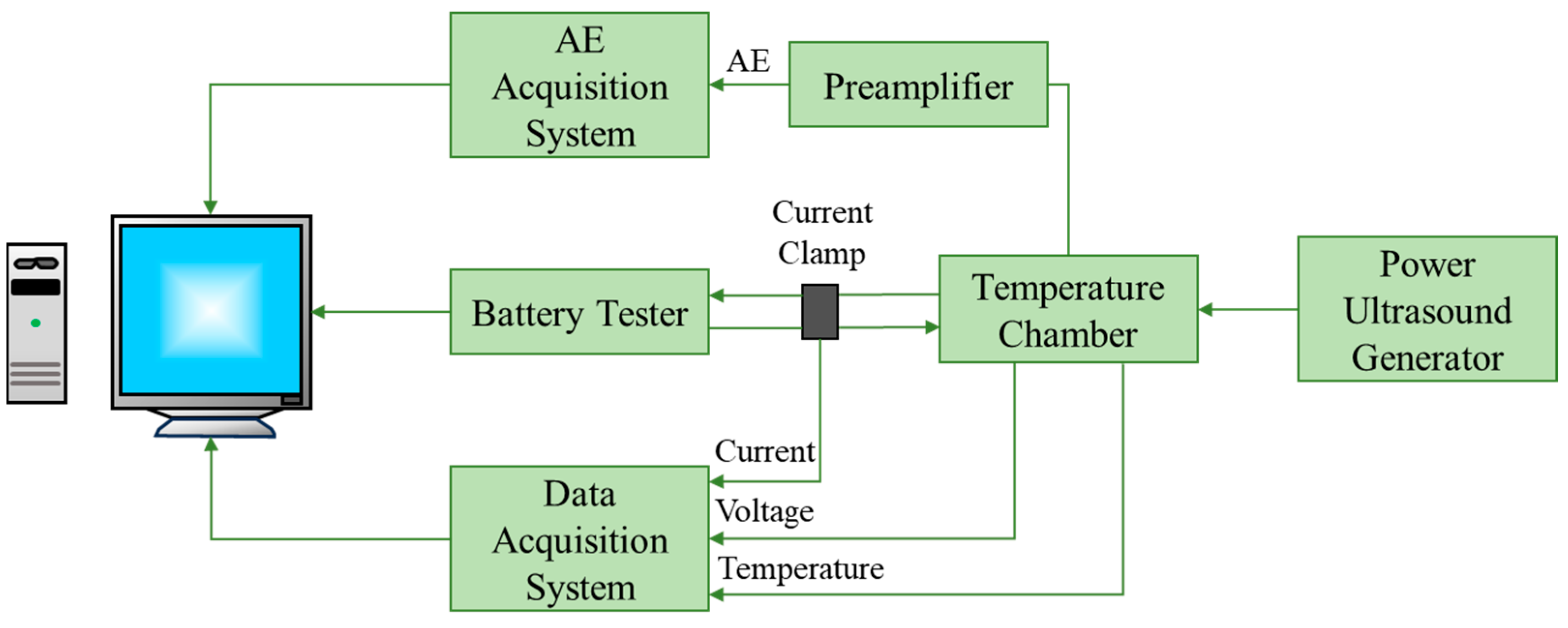

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A. Active acoustic emission sensing for fast co-estimation of state of charge and state of health of the lithium-ion battery. J Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Jo, J.-H.; Byeon, J.-W. Ultrasonic monitoring performance degradation of lithium ion battery. Microelectron. Reliab. 2020, 114, 113859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Acoustic Emission Test and Signal Analysis During Charging and Discharging of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.; Bingchen, Z.; Zidong, Z.; Maoshu, X.; Sheng, W.; Qixing, L.; Haomiao, L.; Min, Z.; Kai, J.; Kangli, W. In situ detection of lithium-ion batteries by ultrasonic technologies. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 62, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yin, J.; He, Y. Acoustic emission detection and analysis method for health status of lithium ion batteries. Sensors 2021, 21, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Gong, H.; He, Z.; Zhang, P.; He, L. Recent advances in applications of power ultrasound for petroleum industry. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2021, 70, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, X. A new model in correlating and calculating the solid–liquid equilibrium of salt–water systems. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 24, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, M.; Chow, R.; Zeqiri, B. High-frequency acoustic emissions generated by a 20 kHz sonochemical horn processor detected using a novel broadband acoustic sensor: A preliminary study. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2004, 11, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitenko, S.I.; Brau, M.; Pflieger, R. Acoustic noise spectra under hydrothermal conditions. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2020, 67, 105189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.E.; Coric, A.; Su, B.; Zhao, Q.; Eriksson, L.; Krysander, M.; Tidblad, A.A.; Zhang, L. Online acoustic emission sensing of rechargeable batteries: Technology, status, and prospects. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 23280–23296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Battery Type | Energy Density | Cycle Life | Safety | Cost | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-ion | High | Long | Moderate Risk | Moderate | Consumer electronics, EVs, Grid storage |

| Redox Flow | Moderate | Very Long | Low Risk | High | Large-scale energy storage |

| Lead-acid | Low | Moderate | Low Risk | Low | Backup power, grid storage |

| Name of the Technology | AE | UT |

|---|---|---|

| The principle of detection | Detect acoustic radiation signals generated when the internal structure of a material changes | Detecting the sound wave signal after the interaction between ultrasonic waves and materials |

| Sound wave frequency | Full frequency band (usually 20 kHz~1 MHz) | Usually ranging from 0.1 to 15 MHz |

| Signal parameter indicators | Peak frequency and intensity | Flight time and peak intensity |

| Testing equipment | 1 acoustic probe | 2 acoustic probes |

| The way of detection | Passive detection | Active detection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, K. Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology. Energies 2025, 18, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051068

Pan Y, Xu K, Wang R, Wang H, Chen G, Wang K. Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051068

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Yuanyuan, Ke Xu, Ruiqiang Wang, Honghong Wang, Guodong Chen, and Kai Wang. 2025. "Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology" Energies 18, no. 5: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051068

APA StylePan, Y., Xu, K., Wang, R., Wang, H., Chen, G., & Wang, K. (2025). Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology. Energies, 18(5), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051068