Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced SCADA Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

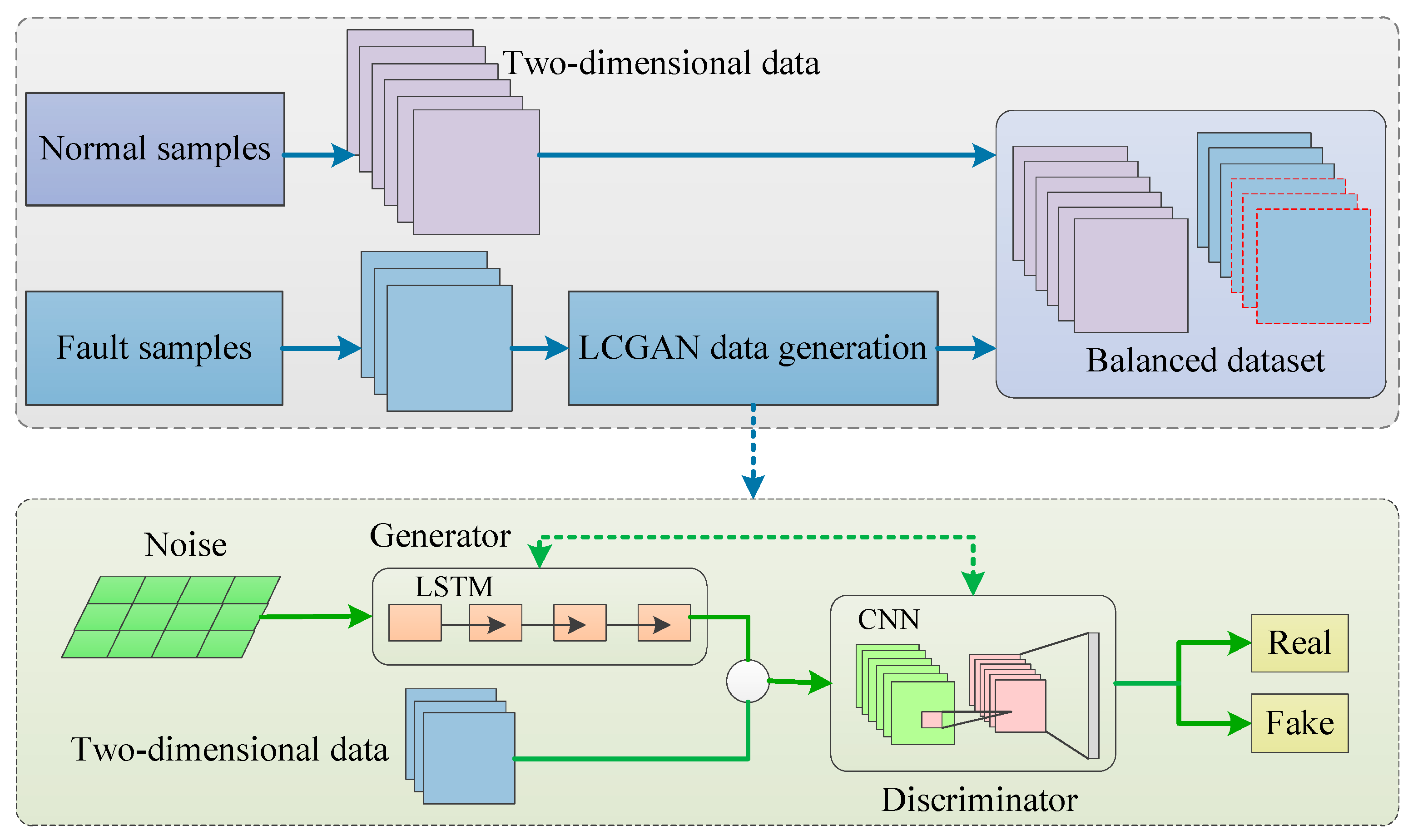

- A novel LCGAN data generation model is proposed to learn the distributions of the real SCADA data samples and deal with the class imbalance problem. Afterwards, an additional CNN model is built to perform the fault classification task using the augmented dataset. The proposed fault diagnosis approach integrating LCGAN data generation and CNN fault classification can enhance the fault diagnosis performance.

- In the proposed LCGAN model, generator and discriminator networks are designed separately. Specifically, LSTM is used in the generator network to learn the temporal correlations from SCADA data, thereby creating samples with temporal dependencies. Moreover, the CNN is employed in the discriminator network to extract complex feature representations, enabling better judgment of the authenticity of the samples. And data can be generated through continuous adversarial learning between the two networks.

- The efficacy of the proposed fault diagnosis approach is confirmed using SCADA data from actual wind turbines, and comparative experiments are performed.

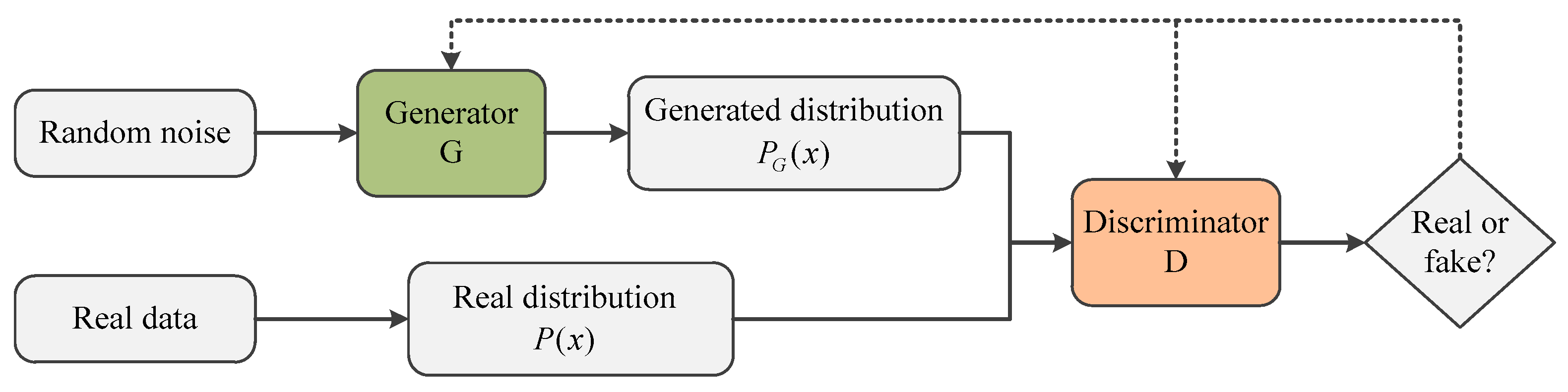

2. Theoretical Background of Generative Adversarial Networks

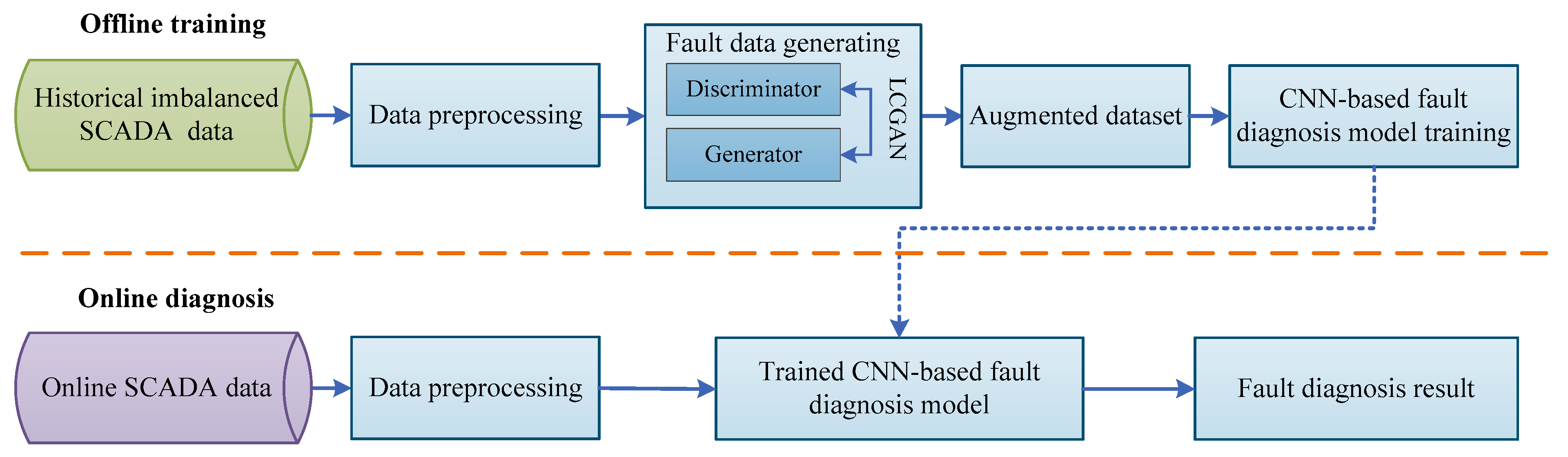

3. Proposed Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis Method

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Method

- Offline training phase: Historical imbalanced SCADA data with normal and fault conditions are first collected. For different health conditions, necessary data preprocessing, including data normalization as well as two-dimensional fragment segmentation, is then carried out. Further, the LCGAN model is employed to produce fault data. These produced data are then merged into the original imbalanced dataset for data augmentation. At last, based on the expanded balanced dataset, the CNN-based fault diagnosis model is trained for wind turbine fault classification and identification.

- Online diagnosis phase: Online SCADA data are acquired and then preprocessed in the same manner as in the offline phase. Afterwards, the data are entered into the CNN-based fault classification model that has been adequately trained to automatically determine the health condition it belongs to and give the fault classification results.

3.2. LCGAN-Based Data Generation

3.3. Fault Classification

4. Experimental Verification

4.1. Data Description

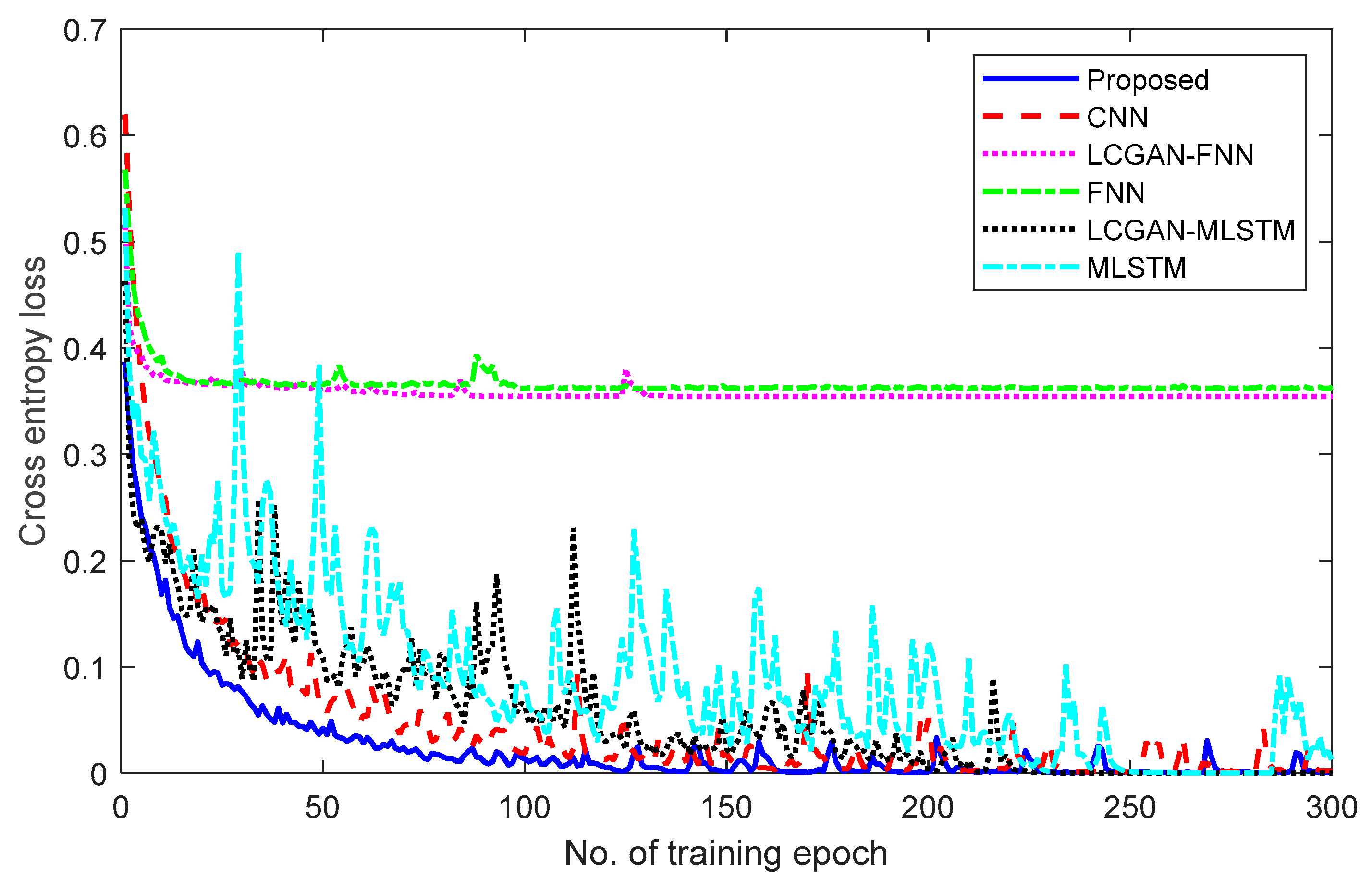

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahimilarki, R.; Gao, Z.; Jin, N.; Zhang, A. Convolutional neural network fault classification based on time-series analysis for benchmark wind turbine machine. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takoutsing, P.; Wamkeue, R.; Ouhrouche, M.; Slaoui-Hasnaoui, F.; Tameghe, T.A.; Ekemb, G. Wind turbine condition monitoring: State-of-the-art review, new trends, and future challenges. Energies 2014, 7, 2595–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Yu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Xiao, H. Reassigned second-order synchrosqueezing transform and its application to wind turbine fault diagnosis. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cui, L.; Zhang, J. Novel morphological scale difference filter with application in localization diagnosis of outer raceway defect in rolling bearings. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 184, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmir, B.; Ninoslav, Z.; Alexandros, S.G.; Nenad, M. Feature extraction using discrete wavelet transform for gear fault diagnosis of wind turbine gearbox. Shock Vib. 2015, 2016, 6748469. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Wang, T.; Yang, H.; Chu, F. Damage identification of wind turbine blades using an adaptive method for compressive beamforming based on the generalized minimax-concave penalty function. Renew. Energy 2022, 181, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshuva, A.; Sugumaran, V. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine blade using vibration signals through j48 decision tree algorithm and random tree classifier. Int. J. Contr. Theory Appl. 2016, 9, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rizk, P.; Rizk, F.; Karganroudi, S.S.; Ilinca, A.; Younes, R.; Khoder, J. Advanced wind turbine blade inspection with hyperspectral imaging and 3D convolutional neural networks for damage detection. Energy AI 2024, 16, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, P.; Younes, R.; Ilinca, A.; Khoder, J. Wind turbine ice detection using hyperspectral imaging. Remote Sens. Appl. 2022, 26, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvela Nieto, M.T.; Gelbhardt, H.; Ohlendorf, J.H.; Thoben, K.D. Detecting ice on wind turbine rotor blades: Towards deep transfer learning for image data. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on System-Integrated Intelligence (SysInt 2022), Genova, Italy, 7–9 September 2022; pp. 574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, P.B. Condition monitoring and fault diagnosis of wind turbines based on structural break detection in SCADA data. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Omariba, Z.B. Ice detection model of wind turbine blades based on random forest classifier. Energies 2018, 11, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Shu, L. Wind turbine fault diagnosis based on Gaussian process classifiers applied to operational data. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wen, T.; Da, Z. Ice detection for wind turbine blades based on PSO-SVM method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1087, 022036. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Xie, P.; He, H.; Yan, J. Wind turbine fault detection using a denoising autoencoder with temporal information. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; He, Q.; Jiang, G.; Xie, P. Spatio-temporal fusion neural network for multi-class fault diagnosis of wind turbines based on SCADA data. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Tao, J.; Zhao, Z. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine pitch system based on LSTM with multi-channel attention mechanism. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 4087–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; He, H.; Yan, J.; Xie, P. Multiscale convolutional neural networks for fault diagnosis of wind turbine gearbox. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 3196–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Kong, X.; Wang, Q.; Cui, H. Intelligent wind turbine blade icing detection using supervisory control and data acquisition data and ensemble deep learning. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estefania, A.; Sergio, M.M.; Andrés, H.E.; Emilio, G.L. Wind turbine reliability: A comprehensive review towards effective condition monitoring development. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Tsai, C.F.; Hu, Y.; Jhang, J. Clustering-based undersampling in classimbalanced data. Inf. Sci. 2017, 409–410, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Novel discriminant locality preserving projections based on improved synthetic minority oversampling with application to fault diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 10th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference, Suzhou, China, 14–16 May 2021; pp. 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liang, G.; Wang, L.; Long, W. Imbalanced data fault diagnosis of rotating machinery using synthetic oversampling and feature learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 48 (Pt C), 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Jiang, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, B. Imbalanced classification based on minority clustering synthetic minority oversampling technique with wind turbine fault detection application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 5867–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Pu, Z.; Du, W.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Improved adversarial learning for fault feature generation of wind turbine gearbox. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.K.; Myung, H. Autoencoder-combined generative adversarial networks for synthetic image data generation and detection of jellyfish swarm. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 54207–54214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Bao, G.; Zhang, D. Multiview generative adversarial network and its application in pearl classification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 8244–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. Dual-discriminator GAN: A GAN way of profile face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 27–29 June 2020; pp. 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.; Deng, C.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, L. A deep capsule neural network with data augmentation generative adversarial networks for single and simultaneous fault diagnosis of wind turbine gearbox. ISA Trans. 2023, 135, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Meng, L.; Kong, X.; Xu, T.; Lan, X.; Li, Y. Generative adversarial networks for gearbox of wind turbine with unbalanced data sets in fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 13285–13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. A research on fault diagnosis of wind turbine CMS based on Bayesian-GAN-LSTM neural network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2417, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the 27th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Ma, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, X. Machinery fault diagnosis with imbalanced data using deep generative adversarial networks. Measurement 2020, 152, 107377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, J.; Cai, Y. Multifactor spatio-temporal correlation model based on a combination of convolutional neural network and long short-term memory neural network for wind speed forecasting. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2019, 185, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, H.; Zhong, D. A review on ice detection technology and ice elimination technology for wind turbine. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Wang, C.; Jiang, F.; Long, M.; Yu, P.S.; Liu, Y. WaveletFCNN: A deep time series classification model for wind turbine blade icing detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.05625. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Variable Description | No. | Variable Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wind speed | 14 | Temperature of pitch motor 1 |

| 2 | Generator speed | 15 | Temperature of pitch motor 2 |

| 3 | Active power | 16 | Temperature of pitch motor 3 |

| 4 | Wind direction | 17 | Horizontal acceleration |

| 5 | Average wind direction angle within 25 s | 18 | Vertical acceleration |

| 6 | Yaw position | 19 | Environmental temperature |

| 7 | Yaw speed | 20 | Internal temperature of nacelle |

| 8 | Angle of pitch 1 | 21 | Switching temperature of pitch 1 |

| 9 | Angle of pitch 2 | 22 | Switching temperature of pitch 2 |

| 10 | Angle of pitch 3 | 23 | Switching temperature of pitch 3 |

| 11 | Speed of pitch 1 | 24 | DC power of pitch 1 switch charger |

| 12 | Speed of pitch 2 | 25 | DC power of pitch 2 switch charger |

| 13 | Speed of pitch 3 | 26 | DC power of pitch 3 switch charger |

| Condition | Size of Training Data | Size of Testing Data |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 3000 | 360 |

| Fault | 1112 | 360 |

| Describe | Layer | Hidden Size/Filter | Kernel Size | Stride | Padding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generator LSTM | LSTM | 128 | |||

| LSTM | 128 | ||||

| FC | 128 | ||||

| Discriminator CNN | Conv2D | 128 | (8,8) | 1 | same |

| BN | |||||

| Conv2D | 256 | (5,5) | 1 | same | |

| BN | |||||

| Conv2D | 128 | (3,3) | 1 | same | |

| BN | |||||

| Global_avg_pool2D | |||||

| FC | 1 |

| Layer | Hidden Size/Filter | Kernel Size | Stride | Padding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D | 64 | (8,8) | 1 | same |

| BN | ||||

| Conv2D | 128 | (5,5) | 1 | same |

| BN | ||||

| Global_avg_pool2D | ||||

| FC | 2 |

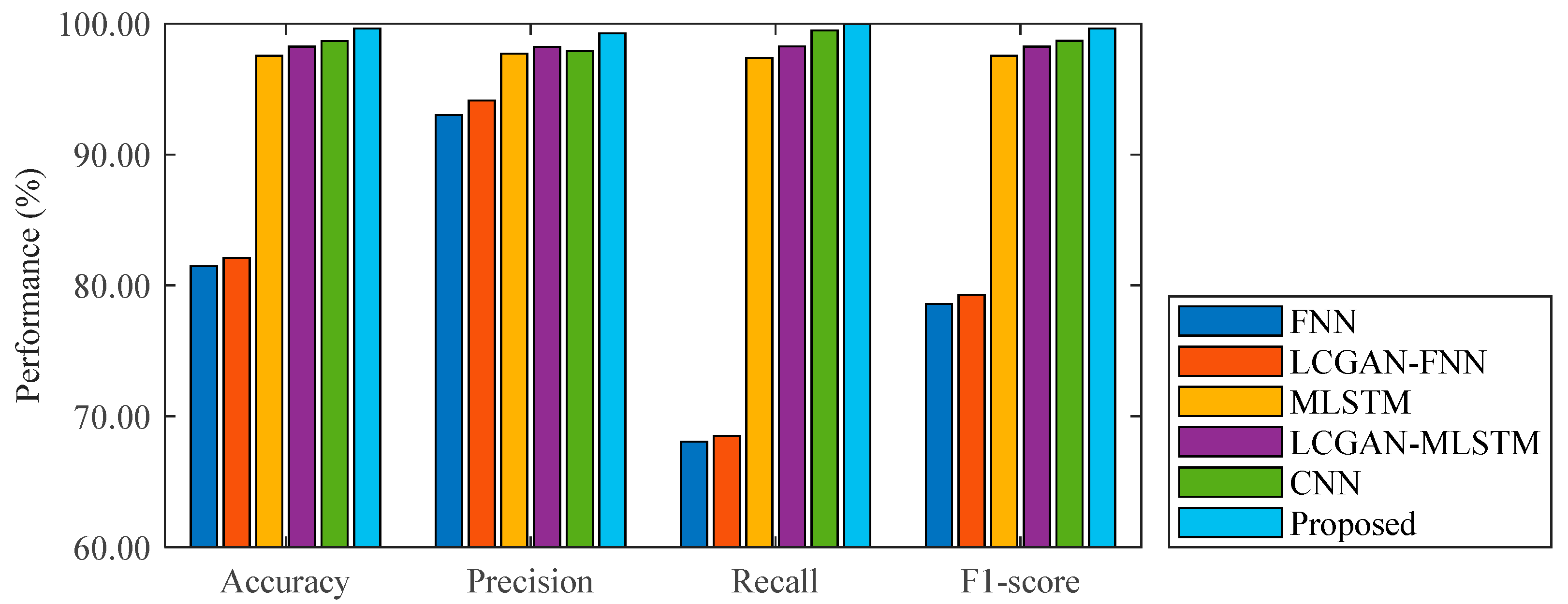

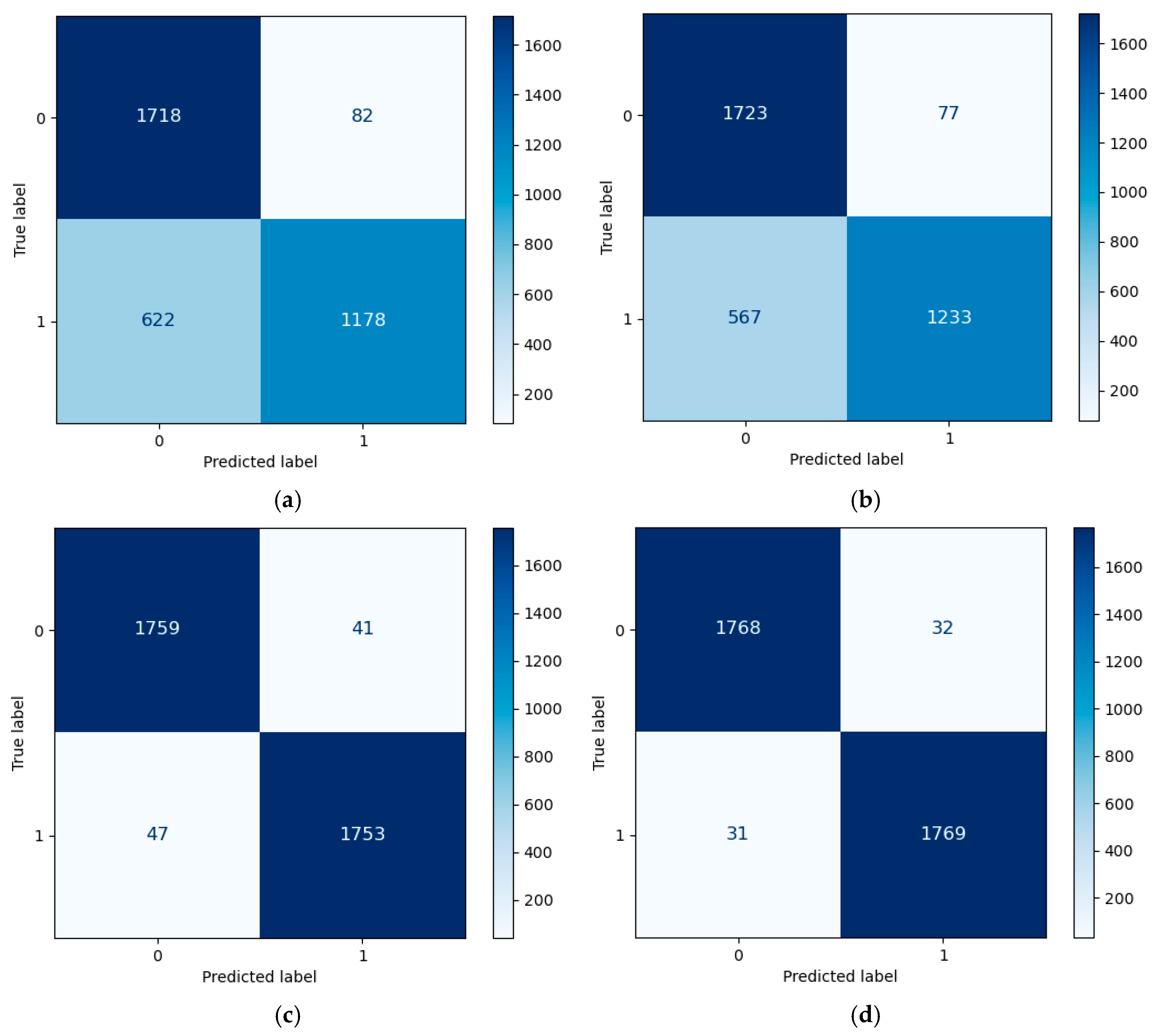

| Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNN | 81.47 | 93.02 | 68.06 | 78.60 |

| LCGAN-FNN | 82.11 | 94.13 | 68.50 | 79.29 |

| MLSTM | 97.55 | 97.72 | 97.39 | 97.55 |

| LCGAN-MLSTM | 98.25 | 98.23 | 98.28 | 98.25 |

| CNN | 98.69 | 97.92 | 99.50 | 98.70 |

| Proposed | 99.64 | 99.28 | 100 | 99.64 |

| Method | Training Time (s) | Testing Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| FNN | 40.28 | 0.01 |

| LCGAN-FNN | 124.47 | 0.02 |

| MLSTM | 43.49 | 0.01 |

| LCGAN-MLSTM | 65.10 | 0.01 |

| CNN | 836.94 | 0.16 |

| Proposed | 1272.32 | 0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Li, T.; Xie, M.; Tian, W.; Han, W. Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced SCADA Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Energies 2025, 18, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051158

Wang H, Li T, Xie M, Tian W, Han W. Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced SCADA Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051158

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hong, Taikun Li, Mingyang Xie, Wenfang Tian, and Wei Han. 2025. "Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced SCADA Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks" Energies 18, no. 5: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051158

APA StyleWang, H., Li, T., Xie, M., Tian, W., & Han, W. (2025). Wind Turbine Fault Diagnosis with Imbalanced SCADA Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Energies, 18(5), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051158