The Influence of Tri-Structural Isotropic Fuel on the Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of SiC Tri-Structural Isotropic Composite Fuels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

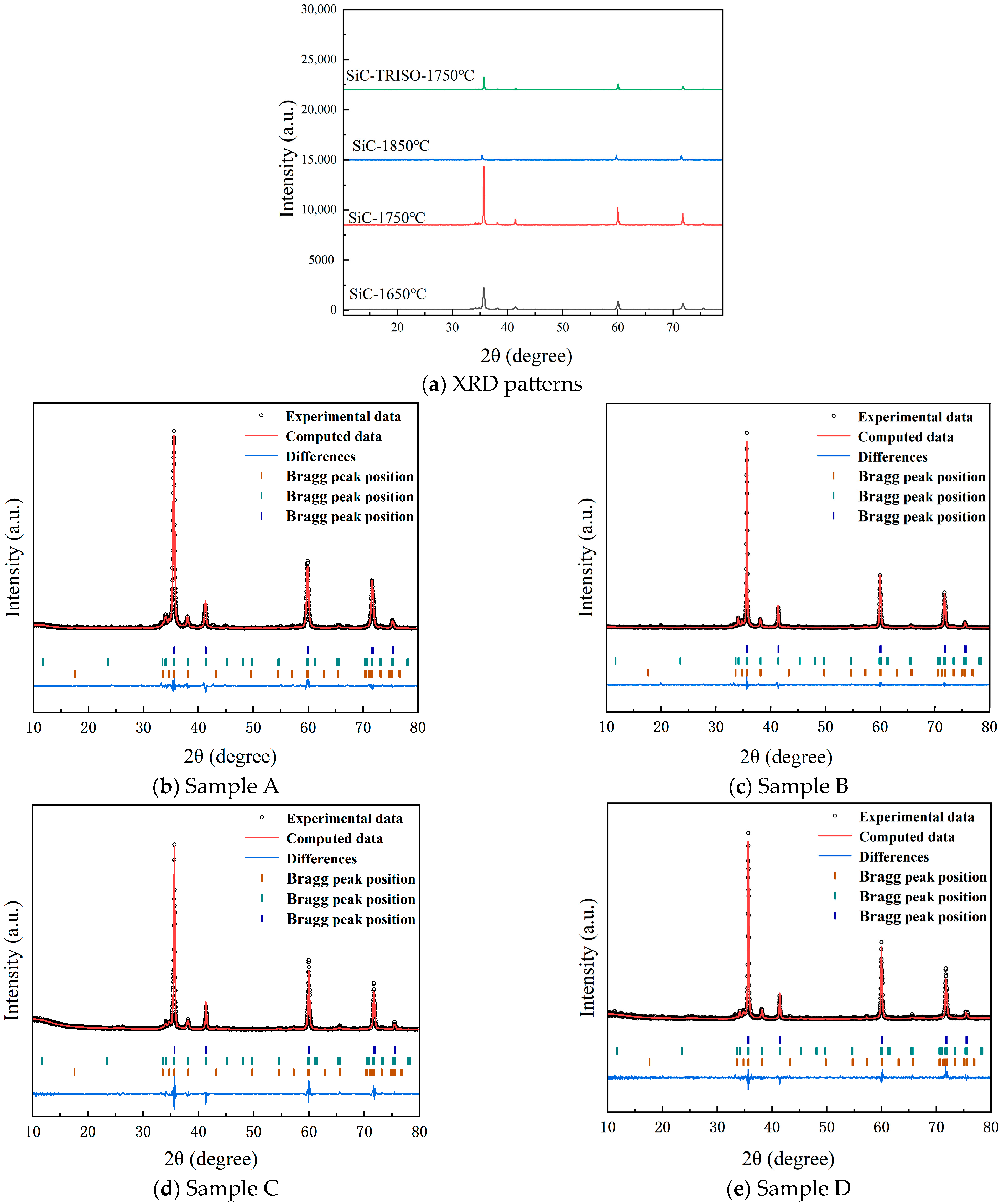

3.1. Phase Transition of SiC at Different Sintering Temperatures

3.2. λ of SiC at Various Sintering Temperatures

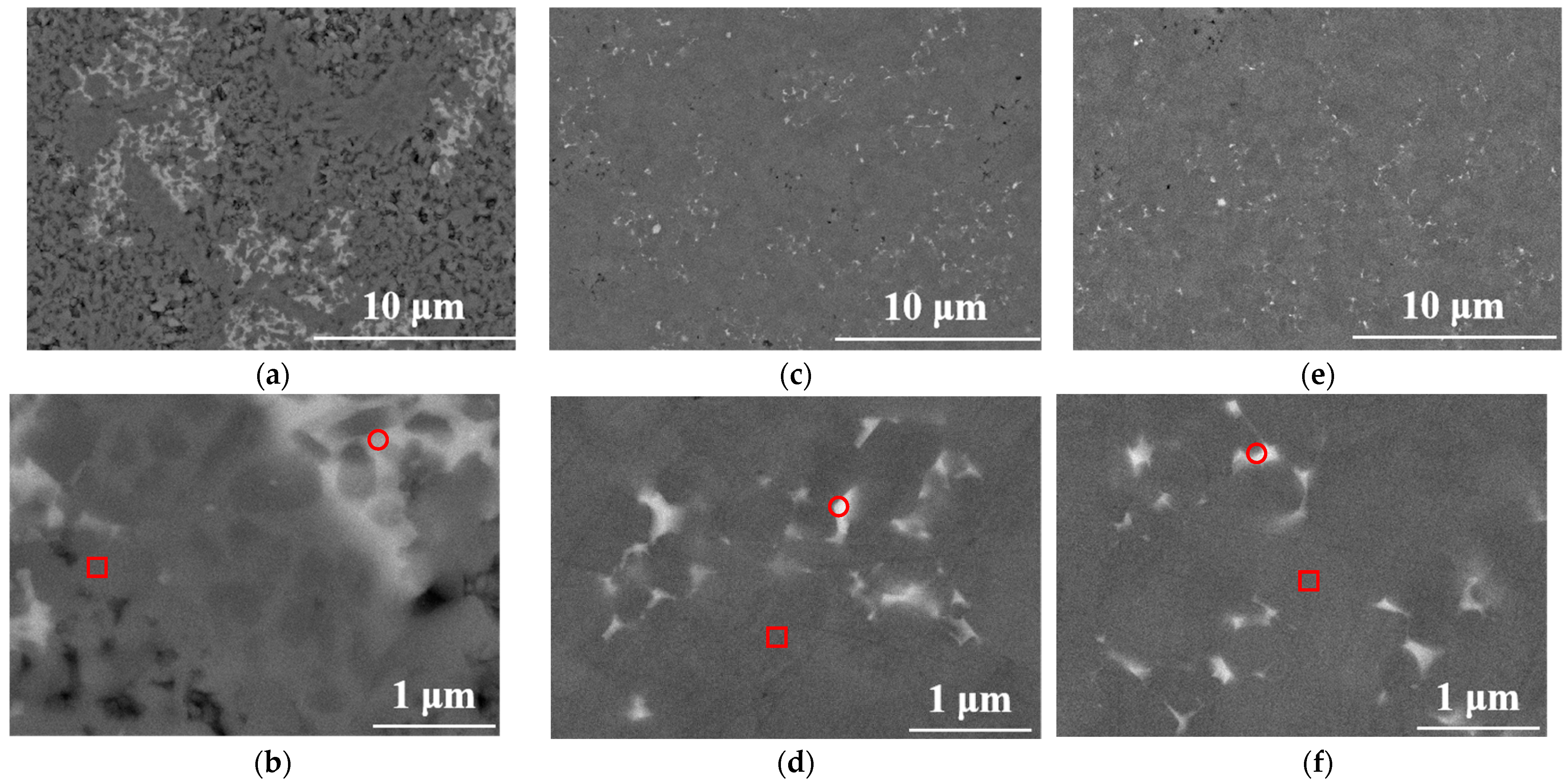

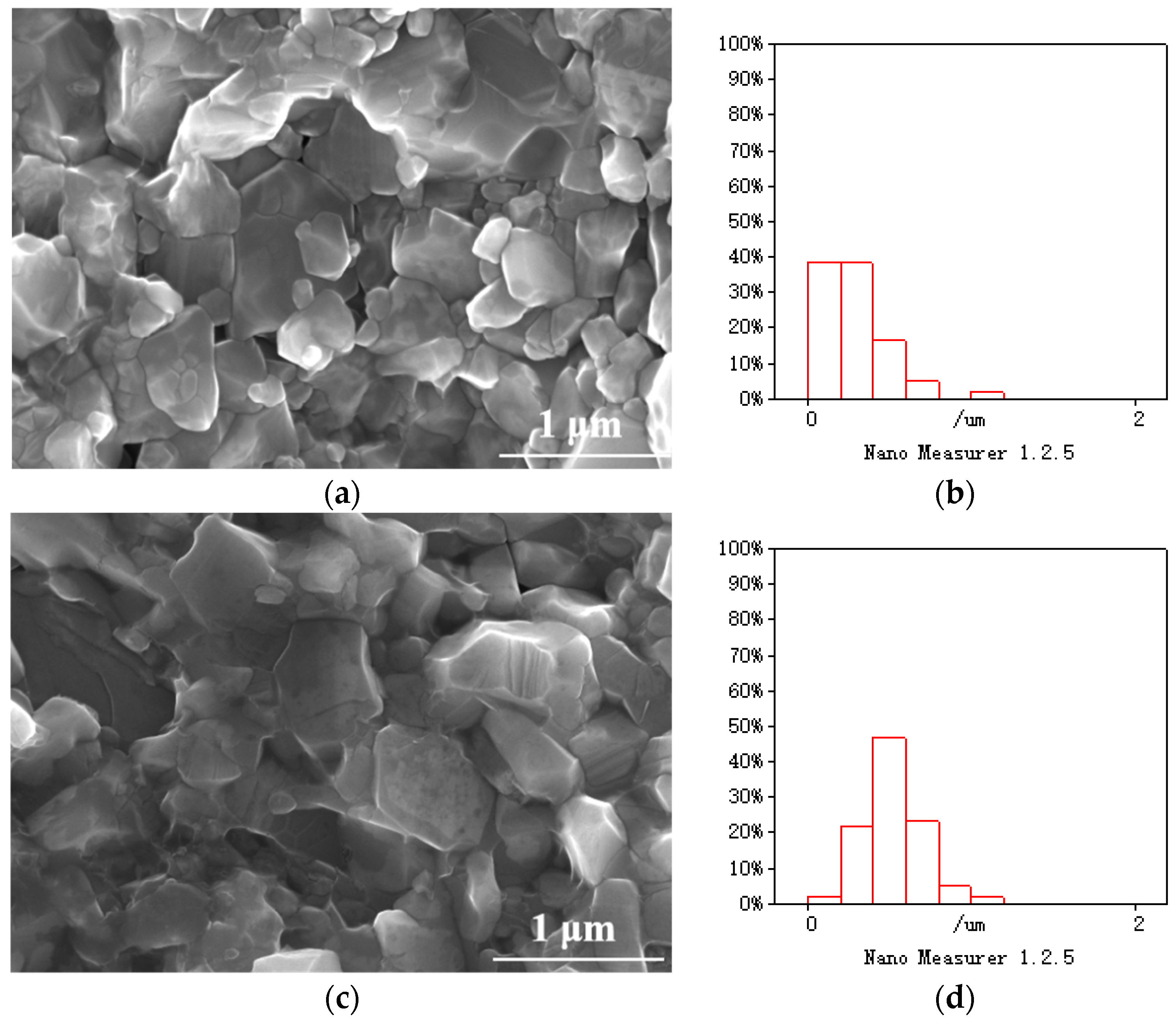

3.3. Microstructure of SiC at Different Sintering Temperatures

3.4. Effect of TRISO Fuel on the Phase Transition of the SiC Matrix

3.5. Thermal Conductivity of SiC-TRISO Composite Fuel

3.6. The Effect of TRISO Fuel on the Microstructure of the Silicon Carbide Matrix

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- After the hot-press sintering of silicon carbide at 1650 °C, 1750 °C, and 1850 °C, the volume fractions of 3C-SiC in the matrix were 91.1%, 90.3%, and 52.2%, respectively. The λ values at room temperature were 18.66, 75.51, and 61.59 , which declined to 15.75, 43.36, and 40.57 at 500 °C.

- (2)

- As the sintering temperature increased, the concentrations of Al, Y, and Ca in both the silicon carbide grains and the liquid-phase region declined, with each element exhibiting a similar reduction of approximately 70%. The observed decrease was attributed to the reaction between silicon carbide and sintering aids, leading to the volatilization of Al, Y, and Ca in gaseous form.

- (3)

- The content of 3C-SiC in the SiC-TRISO composite fuel was determined to be 87.7%, which was 3% lower than that of the SiC sample. The λ values of the SiC-TRISO composite fuel were 57.96 and 34.51 at room temperature and 500 °C, respectively, approximately 20% lower than that of Sample B. The average silicon carbide grain size in the SiC-TRISO composite fuel was twice that of the SiC sample without TRISO particles. Furthermore, TRISO particles facilitated the 3C-SiC→6H-SiC→4H-SiC transformation. Moreover, the carbon layer on the outermost TRISO grains reacted with the liquid phase, promoting grain growth and increasing the free-carbon content. Simultaneously, the diffusion and volatilization of Al, Y, and Ca within the silicon carbide grains were enhanced, thereby reducing the thermal conductivity of the composite fuels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| SI | ||||

| TRISO | Tri-structural Isotropic | XRD | X-ray diffraction | |

| HTGCR | High-temperature gas-cooled reactor | SEM | Scanning electron microscopy | |

| Cp | Heat capacity | EDS | Energy-dispersive spectroscopy | |

| ρ | Density | BSE | Back-scattered electron | |

| λ | Thermal conductivity | SE | Secondary electron |

References

- Fu, Z.; He, L.; van Rooyen, I.J.; Yang, Y. Comparison of microstructural and micro-chemical evolutions in the irradiated fuel kernels of AGR-1 and AGR-2 TRISO fuel particles. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 176, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Song, Q.; Shen, Y.; Lou, L.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, H.; Gu, H. Development and verification of an MC/MOC two-step scheme for neutronic analysis of FCM-fueled micro gas-cooled reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 211, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recuero, A.M.; Singh, G.; Jiang, W. Fracture mechanics approach to TRISO fuel particle failure analysis. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 596, 155083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yang, G.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Liu, M. Numerical study of TRISO particles with random size and location distribution in cuboid and cylindrical matrix: A validation for two-regime heat conduction model. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 423, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, P.; He, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhang, J.; Tian, W.; Su, G.; et al. Preliminary numerical investigation of TRISO-matrix interface debonding characteristics in fully ceramic microencapsulated fuel. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 159, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Di Fulvio, A. Rotation-invariant rapid TRISO-fueled pebble identification based on feature matching and point cloud registration. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2024, 203, 110527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, J.D.; Jiang, W. Versatile TRISO fuel particle modeling in Bison. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 428, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Ding, S.; Ren, Q. Modeling of irradiation-induced thermo-mechanical coupling and multi-scale behavior in a fully ceramic-microencapsulated fuel pellet. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 544, 152673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, Y.A.; Mehboob, K.; Mohamad, D.; Alhawsawi, A.; Abolaban, F.A. Neutronic performance of fully ceramic microencapsulated of uranium oxycarbide and uranium nitride composite fuel in SMR. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 155, 108152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Hong, S.G.; Kwon, H. Conceptual design of a long cycle small modular reactor core with annular UO2 and FCM (TRU) fuels. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 45, 11957–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, V.; Bratten, A.; Shi, M.; Gerczak, T.; Zhao, H.; Poplawsky, J.D.; He, X.; Helmreich, G.; Wen, H. Influence of temperature, oxygen partial pressure, and microstructure on the high-temperature oxidation behavior of the SiC Layer of TRISO particles. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 116913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, C.; Snead, L.; Kato, Y. A logical approach for zero-rupture Fully Ceramic Microencapsulated (FCM) fuels via pressure-assisted sintering route. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 531, 151987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-G.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.J.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, W.-J. Distribution Analysis of TRISO-Coated Particles in Fully Ceramic Microencapsulated Fuel Composites. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2018, 55, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Huang, R.; Lin, H.-T.; Liu, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, R. Fully ceramic microencapsulated fuels with high TRISO particles loading capacity fabricated by gel-casting. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023, 581, 154449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Kim, H.-M.; Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lim, K.-Y.; Lim, K.-Y. Pressureless sintered silicon carbide matrix with a new quaternary additive for fully ceramic microencapsulated fuels. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.S.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lim, K.-Y.; Lee, S.-J. New quaternary additive for processing fully ceramic microencapsulated fuels without applied pressure. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-D.; Kim, Y.-W. Processing of fully ceramic microencapsulated fuels with a small amount of additives by hot-pressing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 3980–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, R.; Tan, J.; Lin, H.-T.; Liu, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, R. Fully ceramic microencapsulated fuels fabricated by tape casting. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 564, 153675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Yuan, R.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, M. Numerical analysis of effective thermal conductivity of FCM with multilayer TRISO particle. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 36, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, J.; Jian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Ding, S.; Ren, Q. Effects of the mesostructures and irradiation conditions on the ther-mo-mechanical coupling behaviors in LWR-used fully ceramic-microencapsulated fuel pellets. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 34, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanovskiy, A.V.; Zeodinov, M.G.; Kostanovskaya, M.E.; Pronkin, A.A. Thermal Conductivity of Silicicated Silicon Carbide at 1400−2200 K. High Temp. 2019, 57, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Watari, K.; Hayashi, H.; Urabe, K. Microstructural Characterization of High-Thermal-Conductivity Aluminum Nitride Ceramic. J. Food Qual. 2002, 85, 3093–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.G.; Orihuela, M.; Ramirez-Rico, J.; Chacartegui, R.; Martínez-Fernández, J. Thermal conductivity of porous biomorphic SiC derived from wood precursors. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 16220–16229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Gui, Z.; Janotti, A.; Ni, C.; Karandikar, P. Strong effect of electron-phonon interaction on the lattice thermal conductivity in 3C-SiC. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2017, 1, 034601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Cho, T.-Y.; Kim, Y.-W.; Nishimura, T.; Narimatsu, E. Electrical and thermal properties of silicon carbide–boron nitride composites prepared without sintering additives. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 4423–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, G.; Xie, R.; Mitomo, M.; Kim, Y. Effect of β-to-α Phase Transformation on the Microstructural Development and Mechanical Properties of Fine-Grained Silicon Carbide Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Mitomo, M.; Hirotsuru, H. Microstructural Development of Silicon Carbide Containing Large Seed Grains. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 80, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, M.A.; Krstic, V.D. Low-temperature pressureless sintering of silicon carbide with aluminum oxide and yttrium oxide additions. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 1991, 70, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Tian, C.; Xiao, H.; Guo, W.; Gao, P.; Liang, J. Effect of B4C on co-sintering of SiC ceramic membrane. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 3921–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerczak, T.J.; Hunn, J.D.; Lowden, R.A.; Allen, T.R. SiC layer microstructure in AGR-1 and AGR-2 TRISO fuel particles and the influence of its variation on the effective diffusion of key fission products. J. Nucl. Mater. 2016, 480, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.J.; Wirth, B.D. A review of TRISO fuel performance models. J. Nucl. Mater. 2010, 405, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample No. | Sample Designation | Sintering Temperature | Polytype Content (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C | 6H | 4H | |||

| A | SiC | 1650 °C | 91 | 9 | <1 |

| B | SiC | 1750 °C | 90 | 4 | 6 |

| C | SiC | 1850 °C | 52 | 38 | 10 |

| Element | Sample A (1650 °C) | Sample B (1750 °C) | Sample C (1850 °C) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiC Grain | Liquid Phase | SiC Grain | Liquid Phase | SiC Grain | Liquid Phase | |

| C | 47.89 ± 0.46 | 17.05 ± 0.38 | 49.50 ± 0.40 | 37.59 ± 0.41 | 51.68 ± 0.64 | 44.74 ± 0.37 |

| Si | 45.24 ± 0.44 | 19.02 ± 0.22 | 42.67 ± 0.38 | 33.62 ± 0.32 | 47.68 ± 0.63 | 31.44 ± 0.29 |

| Al | 2.09 ± 0.08 | 14.90 ± 0.17 | 2.80 ± 0.08 | 5.79 ± 0.10 | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 5.01 ± 0.09 |

| Y | – | 9.53 ± 0.43 | – | 3.86 ± 0.36 | – | 3.12 ± 0.31 |

| Ca | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.10 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.28 ± 0.08 | – | 0.13 ± 0.06 |

| O | 4.57 ± 0.15 | 39.05 ± 0.28 | 4.51 ± 0.14 | 18.86 ± 0.20 | – | 15.55 ± 0.17 |

| No. | C | Si | Al | Y | Ca | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample B | 49.50 ± 0.40 | 42.67 ± 0.38 | 2.80 ± 0.08 | – | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 4.51 ± 0.14 |

| Sample D | 59.63 ± 0.52 | 30.64 ± 0.61 | 1.85 ± 0.13 | – | – | 7.88 ± 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; You, Y.; Zhang, Z. The Influence of Tri-Structural Isotropic Fuel on the Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of SiC Tri-Structural Isotropic Composite Fuels. Energies 2025, 18, 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051216

Wang X, Zhu L, You Y, Zhang Z. The Influence of Tri-Structural Isotropic Fuel on the Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of SiC Tri-Structural Isotropic Composite Fuels. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051216

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaojiao, Libing Zhu, Yan You, and Zhaoquan Zhang. 2025. "The Influence of Tri-Structural Isotropic Fuel on the Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of SiC Tri-Structural Isotropic Composite Fuels" Energies 18, no. 5: 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051216

APA StyleWang, X., Zhu, L., You, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2025). The Influence of Tri-Structural Isotropic Fuel on the Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of SiC Tri-Structural Isotropic Composite Fuels. Energies, 18(5), 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051216