Public Engagement in Energy Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method and Focus

- -

- The formation of research and innovation policy;

- -

- The development of research and innovation programmes;

- -

- The definition of a research and innovation project;

- -

- Actual research and innovation activities.

- (1)

- In December 2013, the Engage 2020 consortium set up an international online survey which was used to collect examples of methods or tools being used at the time to engage civil society stakeholders at all levels of the research and innovation process across all grand societal challenges. The consortium partners invited relevant parties in their networks and professional associations to contribute. The majority of these are professionally organising public engagement, such as science communicators, community-based researchers, and technology-assessors. Over 200 questionnaires were filled out over a period of four months. Based on this input and research on fields of practice in engagement by the consortium [5], 57 methods and tools were identified. For all of the methods and tools a specific factsheet was made, based on the information in the questionnaire and additional desktop research. The report on the factsheets was published online in October 2014 [6].

- (2)

- As part of, and in addition to the work carried out in step 1, we obtained specific information on engagement in energy research; with a focus on engagement during project definition or the actual research and innovation activities. Most of this information was gathered from the Dutch language area. The main catalogues used were:

- -

- National Academic Research and Collaborations Information System (Narcis) of the Dutch Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS);

- -

- SmartCat, which is the University of Groningen’s localized version of WorldCat;

- -

- Web of Science.

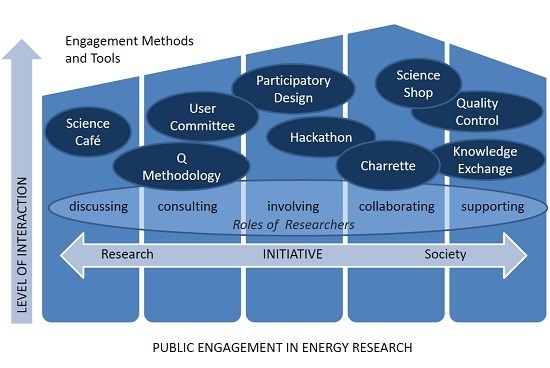

Theoretical Background

- Informing: To provide the public with balanced and objective information to assist them in understanding the problem, alternatives, opportunities and/or solutions;

- Consult: To obtain public feedback on analysis, alternatives, and/or decisions;

- Involve: To work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public issues and concerns are consistently understood and considered;

- Collaborate: To partner with the public in each aspect of the decision including the development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution;

- Empowerment: To place final decision-making in the hands of the public.

3. Results

3.1. Discussing

Science Café

3.2. Consultation

3.2.1. User committee

3.2.2. Q Methodology

- i.

- Definition of the concourse

- ii.

- Interviews and perspective identification

- iii.

- Analysis & Conclusions

- Keep all options open;

- Hit the brakes;

- Support small-scale innovative initiatives;

- Security of supply with global, certified, 2nd generation biomass;

- Efficiency the goal: biomass a means?

- Just do it, step by step.

3.3. Involving

3.3.1. Participatory Design

- i.

- Workshop with communities (citizens engaged in a certain issue), academics & local government, including collaborative mapping sessions, probes and workbooks to feed the discussion;

- ii.

- Fieldwork;

- iii.

- Design & adaptation during deployment.

3.3.2. Hackathon

3.4. Collaborating

3.4.1. Science Shop

3.4.2. Charrette

- i.

- Getting to know each other and the core issues. It can be useful to do a site visit but the information that has been gathered beforehand to bring the participants up to speed is the key;

- ii.

- Gathering input from the participants. In depth interviews in subgroups should be held to gain insight into the views of each stakeholder. Each participant also prioritises the issues that they raise;

- iii.

- Integration.

3.5. Supporting

3.5.1. Knowledge Exchange

3.5.2. Quality Control

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- RRI is an inclusive approach to research and innovation (R & I), to ensure that societal actors work together during the whole research and innovation process. It aims to better align both the process and outcomes of R & I, with the values, needs and expectations of European society. In general terms, RRI implies anticipating and assessing potential implications and societal expectations with regard to research and innovation. In practice, RRI consists of designing and implementing R & I policy that will: Engage society more broadly in its research and innovation activities, increase access to scientific results, ensure gender equality, in both the research process and research content, take into account the ethical dimension, and promote formal and informal science education Science with and for Society—Horizon 2020—European Commission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/science-and-society (accessed on 12 October 2015).

- Next to these motives, governments also want to engage people in research to make society enthusiastic and knowing about science and technology, in order to have an abundant, well trained, technically informed labour force; also governments want to share scientific findings because they are part of our cultural development.

- The Grand Challenges as defined by the European Commission are: Health, demographic change and wellbeing; Food security, sustainable agriculture and forestry, marine and maritime and inland water research, and the Bio economy; Secure, clean and efficient energy; Smart, green and integrated transport; Climate action, environment, resource efficiency and raw materials; Europe in a changing world—Inclusive, innovative and reflective societies; Secure societies—Protecting freedom and security of Europe and its citizens. See for more information: Societal Challenges—Horizon 2020—European Commission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/societal-challenges (accessed on 12 October 2015).

- For more information on the Engage 2020 project, the consortium members and publications see the website. Available online: http://www.engage2020.eu (accessed on 27 November 2014).

- Hennen, L.; Pfersdorf, S. Public Engagement—Promises, Demands and Fields of Practice, 2014. Available online: http://engage2020.eu/media/D2.1-Public-Engagement-Promises-demands-and-fields-of-practice.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Tools and Instruments for a Better Societal Engagement in “Horizon 2020” (Engage2020 Consortium, October 2014). Available online: http://engage2020.eu/media/D3.2-Public-Engagement-Methods-and-Tools.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2014).

- Arnstein, S.R.J. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundations of Public Participation (International Association for Public Participation (IAP2)). Available online: http://www.iap2.org.au/documents/item/83 (accessed on 5 December 2014).

- We decided to use 5 different forms of engagement, whereas in the Engage2020 project uses 6; we omitted engagement where the citizens or civil society has the “direct decision” on research. We deviate from the project here, since we do not consider this “engagement”, though one could argue that at least in establishing research policy this is what democracy demands.

- Science Cafés|NOVA. Available online: http://sciencecafes.org/for-organizers/ (accessed on 13 June 2014).

- Kenniscafé Groningen: Schaliegas. Available online: http://www.rug.nl/research/energy/news/agenda/kenniscafe-groningen-schaliegas (accessed on 31 May 2014).

- Powell, M. Science Café. In Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Communication; Hornig-Priest, S., Ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 688–690. [Google Scholar]

- Navid, E.L.; Einsiedel, E.F. Synthetic biology in the Science Café: What have we learned about public engagement? J. Sci. Commun. 2012, 11, A02:1–A02:9. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, A.M.; Critchley, C.R. Nanotechnology in Dutch science cafés: Public risk perceptions contextualised. Public Underst. Sci. 2016, 25, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Task and method of working—STW User Committee (Technology Foundation STW, May 2014). Available online: http://stw.nl/sites/stw.nl/files/mediabank/TaskAndMethod-STW-UserCommittee.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2014).

- Künneke, R. MVI Project Windenergie Onderzoeksvoorstel Publieksversie. Available online: http://www.tki-windopzee.nl/files/2013-05/MVI%20project%20windenergie%20onderzoeksvoorstel%20publieksversie.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Responsible Innovation—Project summaries. (Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), January 2010). Available online: http://www.nwo.nl/binaries/content/documents/nwo-en/common/documentation/application/gw/responsible-innovation/responsible-innovation---project-summaries/Responsible+Innovation+%7C+Project+Summaries.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2014).

- Di Ruggero, O.; Thissen, W.A.H. TU Delft: Technology, Policy and Management: Multi Actor Systems; TU Delft, Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppen, E.; Breukers, S.; Hisschemöller, M.; Bergsma, E. Q methodology to select participants for a stakeholder dialogue on energy options from biomass in the Netherlands. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, E.H.W.J. Putting Perspectives into Participation: Constructive Conflict Methodology for Problem Structuring in Stakeholder Dialogues; Uitgeverij BOXPress: Oisterwijk, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC|Energy & Co-Designing Communities|Process. Available online: http://www.ecdc.ac.uk/# (accessed on 31 July 2014).

- ECDC|Energy & Co-Designing Communities|Background. Available online: http://www.ecdc.ac.uk/# (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Boucher, A.; Bowers, J.; Cameron, D.; Jarvis, N.; Gabrys, J.; Gaver, W.; Kerridge, T.; Michael, M.; Wilkie, A. Sustainability, Invention and Energy Demand Reduction: Co-Designing Communities and Practice. Available online: http://research.gold.ac.uk/4782/1/ecdc_poster_4.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Innovatieprogramma Intelligente Netten (IPIN) Position paper kennis—En leertraject, thema Gebruikersbenadering en gebruikersonderzoek (Agency NL—Ministry of Economic Affairs, July 2013). Available online: http://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2013/08/Position%20paper%20Gebruikersbenadering%20en%20gebruikersonderzoek-ipin_0.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Mourik, R. Power Matching City: Power to the People? 2014. Available online: http://www.ieadsm.org/Files/Tasks/Task%2024%20-%20Closing%20the%20Loop%20-%20Behaviour%20Change%20in%20DSM,%20From%20Theory%20to%20Policies%20and%20Practice/Publications/Power%20to%20the%20People_final%20report%20Subtask%202_Netherlands.doc (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Gasunie. Implementation of Smart Grids Could Generate €3.5 Billion for the Netherlands. Press Release 16 April 2015. Available online: http://www.gasunie.nl/en/news/implementation-of-smart-grids-could-generate-eur35-billion-for-th (accessed on 19 October 2015).

- Engage 2020—actioncatalogue.eu. Hackathon. Available online: http://actioncatalogue.eu/method/7392 (accessed on 19 October 2015).

- Apps for Energy Wiki. Available online: http://wiki.appsforenergy.nl/Main_Page (accessed on 12 December 2014).

- “Slurpers” Beste App for Energy. Available online: http://news.utrechtinc.nl/89871-slurpers-beste-app-for-energy (accessed on 6 January 2015).

- Kaye, G. Grassroots Involvement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, G.P. The Sound of High Winds: The Effect of Atmospheric Stability on Wind Turbine Sound and Microphone Noise; University of Groningen: Groningen, the Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer. Besluit van 14 Oktober 2010 Tot Wijziging van Het Besluit Algemene Regels Voor Inrichtingen Milieubeheer en Het Besluit Omgevingsrecht (Wijziging Milieuregels Windturbines). Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2010-749.html (accessed on 8 October 2015). (In Dutch)

- Some, including us, would favour the word “expressed” here instead of “experience”.

- Science Shops. Available online: http://www.livingknowledge.org/livingknowledge/science-shops (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Dublin Descriptors—ECApedia. Available online: http://ecahe.eu/w/index.php/Dublin_Descriptors (accessed on 20 January 2016).

- Wetenschapswinkel WUR, 2010. Wageningen UR. Jubileummagazine 25 jaar Wetenschapswinkel. p. 29. Available online: http://edepot.wur.nl/140385 (accessed on 22 February 2016).

- Mulder, H.; Straver, G. Strengthening Community-University Research Partnerships: Science Shops in the Netherlands. In Strengthening Community University Research Partnerships: GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES; Hall, B., Tandon, R., Tremblay, C., Eds.; UNESCO Chair in Community Based Research and Social Responsibility in Higher Education; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2015; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Extra|Bosch Slabbers. Available online: http://www.bosch-slabbers.nl/Extra/Labrem/Labrem3/# (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Noorman, K.J.; de Roo, G. Energielandschappen, de 3de generatie; Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Assen, The Netherlands, 2011. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Participatory Methods Toolkit. A Practitioner’s Manual; New Edition. Available online: http://www.kbs-frb.be/publication.aspx?id=294864&langtype=1033 (accessed on 28 July 2014).

- Charrette. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopaedia. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charrette&oldid=595193961 (accessed on 13 July 2014).

- Shirk, J.L.; Ballard, H.L.; Wilderman, C.C.; Phillips, T.; Wiggins, A.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Minarchek, M.; Lewenstein, B.V.; Krasny, M.E.; et al. Public Participation in Scientific Research: A Framework for Deliberate Design. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 29:1–29:20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Een Onderzoeksagenda Vanuit Lokale Initiatieven. (HIER opgewekt). Available online: http://www.hieropgewekt.nl/sites/default/files/u11/7.4_een_onderzoeksagenda_vanuit_lokale_initiatieven_def.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Prof. Frans Stokman: “The revolution in energy production is beginning at local level”|News articles|News|University of Groningen. Available online: http://www.rug.nl/news/2012/11/37fransstokman (accessed on 19 October 2015).

- Geschiedenis. Available online: https://milieudefensie.nl/onsverhaal/geschiedenis (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Milieu Centraal Geeft Raad over Luizen, Wasmachines en Auto’s|Voordeel. Available online: http://www.volkskrant.nl/voordeel/milieu-centraal-geeft-raad-over-luizen-wasmachines-en-auto-s~a460096/ (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Over Milieu Centraal. Available online: http://www.milieucentraal.nl/over-milieu-centraal/ (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- Energie Besparen. Available online: http://www.milieucentraal.nl/energie-besparen/ (accessed on 8 October 2015).

- REF 2014. Available online: http://www.ref.ac.uk/ (accessed on 20 January 2016).

- Standard Evaluation Protocol|VSNU. Available online: http://www.vsnu.nl/sep (accessed on 8 April 2015).

- Valorisatie|VSNU. Available online: http://www.vsnu.nl/valorisatie (accessed on 22 February 2016).

| Discussing | Consulting | Involving | Collaborating | Supporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharing information about research & innovation and opening up channels for discussion and interactive communication. No “strings attached“. | Requesting visions on research and innovation processes, and facilitating contributions and structured discussions. There are “strings attached“. | Creating opportunities for contributions to deliberations and research activities or contributing to research execution as more than a subject in the project. | Working together on research initiation and/or execution, so there is co-ownership of the project. | Societal actors are in the lead in the research initiation and execution. On their request, they are supported by researchers or institutions. |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jellema, J.; Mulder, H.A.J. Public Engagement in Energy Research. Energies 2016, 9, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/en9030125

Jellema J, Mulder HAJ. Public Engagement in Energy Research. Energies. 2016; 9(3):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/en9030125

Chicago/Turabian StyleJellema, Jako, and Henk A. J. Mulder. 2016. "Public Engagement in Energy Research" Energies 9, no. 3: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/en9030125

APA StyleJellema, J., & Mulder, H. A. J. (2016). Public Engagement in Energy Research. Energies, 9(3), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/en9030125