Thermo-Electro-Mechanical Simulation of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Gas Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Micro-Hotplate Fabrication

1.2. Sensing Film Deposition

2. SMO Gas Sensor

2.1. Gas Sensing Mechanisms

2.2. SMO Sensor

- The main concerns with the mechanical stability of SMO sensors is due to the need of high temperature operation of the metal oxide film. Regularly heating a device to temperatures between 250 C and 500 C from room temperature and then cooling them back down results in added mechanical stresses and poor stability in all involved layers. Allowing for a reduction in the operating temperature to levels below 100 C would lead to an improved stability, reliability, and power consumption.

- In order to operate at high temperatures, a microheater must be integrated underneath the sensing layer. Due to this requirement, thermal isolation must be provided from the surrounding devices, complicating the fabrication process and demanding a MEMS suspended membrane. Furthermore, the temperature provided has a large impact on the sensing response, while knowing the exact microheater behavior is not always possible, especially since the properties of the microheater materials change with time under operation. These changes can be brought up by the induced thermal stresses, thermo-migration, or electro-migration [47].

- The SMO’s selectivity is another concern. This is currently being addressed by introducing a sensor array, where multiple sensors are individually engineered to increase their selectivity towards a particular gas [50,51,52,53,54,55]. By combining many sensors, each with a prevalent response towards a particular gas, the collected data set can be post-processed to better pin-point which gas or gases are adsorbed at the surface [56]. The requirement of added post-processing makes efficient CMOS integration even more essential, since integration with CMOS electronics would allow the sensor to operate at increased speeds while reducing the power and signal losses readily associated with long interconnect lines.

- There are several research groups looking into the processes taking place during the SMO sensors’ operation; however, a full understanding is as of yet not available. Until recently, it was thought that sensing was only due to a redox surface reaction with adsorbed oxygen. However, it was not long ago shown that even when oxygen is not present, a thin accumulation layer can form at the SMO film’s surface. This layer is formed due to the direct adsorption of gas molecules by the surface oxygen vacancies and results in a change in the film’s resistivity. Many studies also show that adding a dopant to an SMO film can improve the sensitivity or selectivity towards desired gases. Modeling all the simultaneously-occurring phenomena, including dopant influences, is not currently available. Such a predictable model would be very beneficial towards developing a technology computer aided design (TCAD) environment for the design and optimization of SMO sensors.

- Due to the nature of the sensing mechanism, gas molecules can remain adsorbed to the surface even after a sensing cycle has already concluded. In industrial applications, annealing to higher temperatures in clean air or vacuum (above 500 C) promotes the removal of adsorbed species and surface contaminants; however, this is not feasible in portable electronics [57]. Ideally, the simple cooling to room temperature should result in the desorption of all species on the surface, but this is not the case and a removal procedure must be incorporated in the portable device. Removing the previous species is essential in order to ensure that all initially available surface adsorption sites are once again ready for the next measurement cycle.

- As can be expected, the surface of the sensitive SMO film must be exposed to the ambient in order to interact with the target gas molecules. Therefore, its deposition must be performed at the end of the CMOS front end of line sequence. This means that the deposition must proceed at low temperatures, not exceeding the typical back end of line (BEOL) fabrication temperature of about 400 C.

- A microheater element is the essential component used to heat the SMO layer locally to quite high temperatures to ensure enough energy is reached to initiate gas sensing. Here we concentrate on several modeling and simulation aspects for the membrane which is required to house the microheater/sensor element as well as the microheater itself.

2.3. Choice of Sensing Film

3. Modeling the SMO Sensor Structure

3.1. Fabrication

- Wet chemical etching: After a 150 min KOH bath with a concentration of 30% at 70 C the right size of hole was generated and the suspended membrane was released. The etch rate for the silicon wafer depends on the crystallographic orientation which, under the processing setup used, was found to be 13.3 nm/s, 24.2 nm/s, 0.1 nm/s and 23.9 nm/s for directions <100>, <110>, <111>, and <311>, respectively. Although the final structure, shown in Figure 4a appears to be very smooth and clean, with no unwanted lateral etching, the wet chemical etching step can be very corrosive to FEOL devices and surrounding features. Therefore, as an additional alternative analysis using plasma etching was carried out for the same structure. Plasma etching is a commonly used process in CMOS fabrication, which is much less corrosive than a wet chemical bath.

- Dry plasma etching: The simulation for plasma etching involves a stochastic approach for particles which represent the molecules, atoms, and ions, all commonly found in a plasma etch chamber. While not all particles which are found in the chamber contribute to the etch rate, the ones which do are simulated using Monte Carlo ray tracing. The particles can be neutral or charged, representing the chemical and physical accelerated ion etch components, respectively. Because the physical etching component etches layers indiscriminately, the chemical etch is the main contributor, since it can be more selective. However, the negative aspect is the resulting lateral etch, since chemical etching is non-directional. In Figure 4b the increased amount of lateral etching is evident. This simulation setup involved an SF plasma chemistry with a surface fluorine flux of 1 × 10 cm s. The required plasma etch time was found to be much shorter than the wet chemical bath, as a 300 s etch was long enough to fully expose the membrane, as shown in Figure 4b.

3.2. Mechanical Stability

3.3. Electro-Thermo-Mechanical Analysis

3.3.1. Electro-Thermal Behavior

3.3.2. Thermo-Mechanical Behavior

4. Modeling the Thermal Response

4.1. Heater Materials

4.2. Heater Designs

4.3. Heat Loss Mechanisms

4.3.1. Conduction

4.3.2. Convection

4.3.3. Radiation

4.4. Transient Response

5. Modeling the SMO Sensing Mechanism

5.1. SMO Conductivity

5.2. Surface Reactions

- In an inert environment (e.g., N) the surface energy bands are flat and no depletion or accumulation region is present. The number of charges at the surface is the same as that found in the bulk.

- When oxygen is present in the environment, the oxygen vacancies found on the surface of the SMO film are filled by adsorbed O or O and one or two charges are trapped, respectively. The bulk donates one or two electrons to the adsorbed oxygen and a depletion region is formed, resulting in energy band bending, depicted in Figure 18a.

- When CO gas is in the ambient together with O gas the oxygen will be adsorped on the surface and subsequently removed by CO to form CO. The surface will, thereby continuously re-oxidize, leading to a reduction in the depletion region, which depends on the amount of CO found. This is depicted in Figure 18b.

- If only a target gas is present without any oxygen, an oxygen vacancy at the surface of the SMO film can react with a CO molecule, ultimately reducing the surface. In this interaction, CO donates an electron on the surface, forming an accumulation region, depicted in Figure 18c.

5.2.1. Mass Action Law

5.2.2. Power Law Response

5.2.3. Langmuir Adsorption Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| ADC | analog-to-digital converter |

| BEOL | back end of line |

| CAD | computer aided design |

| CMOS | complementary metal oxide semiconductor |

| CTE | coefficient of thermal expansion |

| CVD | chemical vapor deposition |

| DRIE | deep reactive ion etching |

| FEM | finite element method |

| FEOL | front end of line |

| KOH | potassium hydroxide |

| IoE | internet of everything |

| IoT | internet of things |

| IR | infrared |

| ITO | indium tin oxide |

| MEMS | micro-electro-mechanical systems |

| RC | resistance/capacitance |

| RF | radio frequency |

| RAM | random access memory |

| ROM | read-only memory |

| SMO | semiconductor metal oxide |

| TCAD | technology computer aided design |

| TCR | temperature coefficient of resistance |

References

- Martinelli, G.; Carotta, M.C.; Ferroni, M.; Sadaoka, Y.; Traversa, E. Screen-printed perovskite-type thick films as gas sensors for environmental monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1999, 55, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotta, M.C.; Ferroni, M.; Gnani, D.; Guidi, V.; Merli, M.; Martinelli, G.; Casale, M.; Notaro, M. Nanostructured pure and Nb-doped TiO2 as thick film gas sensors for environmental monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1999, 58, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, G.F.; Cavanagh, L.M.; Afonja, A.; Binions, R. Metal oxide semi-conductor gas sensors in environmental monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 5469–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Mu, X.; Yang, Y.; Mason, A.J. Low power multimode electrochemical gas sensor array system for wearable health and safety monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 14, 3391–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.; Müller, R.; Plog, C.; Knezevic, A.; Leye, H.; Irion, E.; Braun, T.; Marquardt, K.J.; Binder, K. Selective ammonia exhaust gas sensor for automotive applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 83, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, J.; Neumann, H.; Wiedenmann, H.M. Exhaust gas sensors for automotive emission control. Solid State Ion. 2002, 152, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, D.J.; Grand, J.; Ting, V.P.; Burke, R.D.; Edler, K.J.; Bowen, C.R.; Mintova, S.; Burrows, A.D. Gas sensing using porous materials for automotive applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4290–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gu, H.; Swager, T.M. Carbon nanotube/polythiophene chemiresistive sensors for chemical warfare agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 5392–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomchenko, A.A.; Harmer, G.P.; Marquis, B.T. Detection of chemical warfare agents using nanostructured metal oxide sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 108, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, R.; Cho, S.; Song, M.J.; Lee, W. Highly sensitive gas sensor based on Al-doped ZnO nanoparticles for detection of dimethyl methylphosphonate as a chemical warfare agent simulant. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 221, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.E. Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Electronics 1965, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, W.; Brillouët, M.; Cogez, P.; Graef, M.; Huizing, B.; Mahnkopf, R. More-Than-Moore White Paper. ITRS, 2010. Available online: http://itrs2.net/uploads/4/9/7/7/49775221/irc-itrs-mtm-v2_3.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Zhang, G.Q.; van Roosmalen, A. (Eds.) More Than Moore: Creating High Value Micro/Nanoelectronics Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggelaar, R.M.; Sanders, R.G.; Groenland, A.; Gardeniers, J.G. Stability of thin platinum films implemented in high-temperature microdevices. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2009, 152, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, A.; Cocuzza, M.; Perrone, D.; Pirri, C.; Mosca, R.; Villani, M.; Delmonte, N.; Zappettini, A.; Calestani, D.; Marasso, S. Modeling, fabrication and testing of a customizable micromachined hotplate for sensor applications. Sensors 2017, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

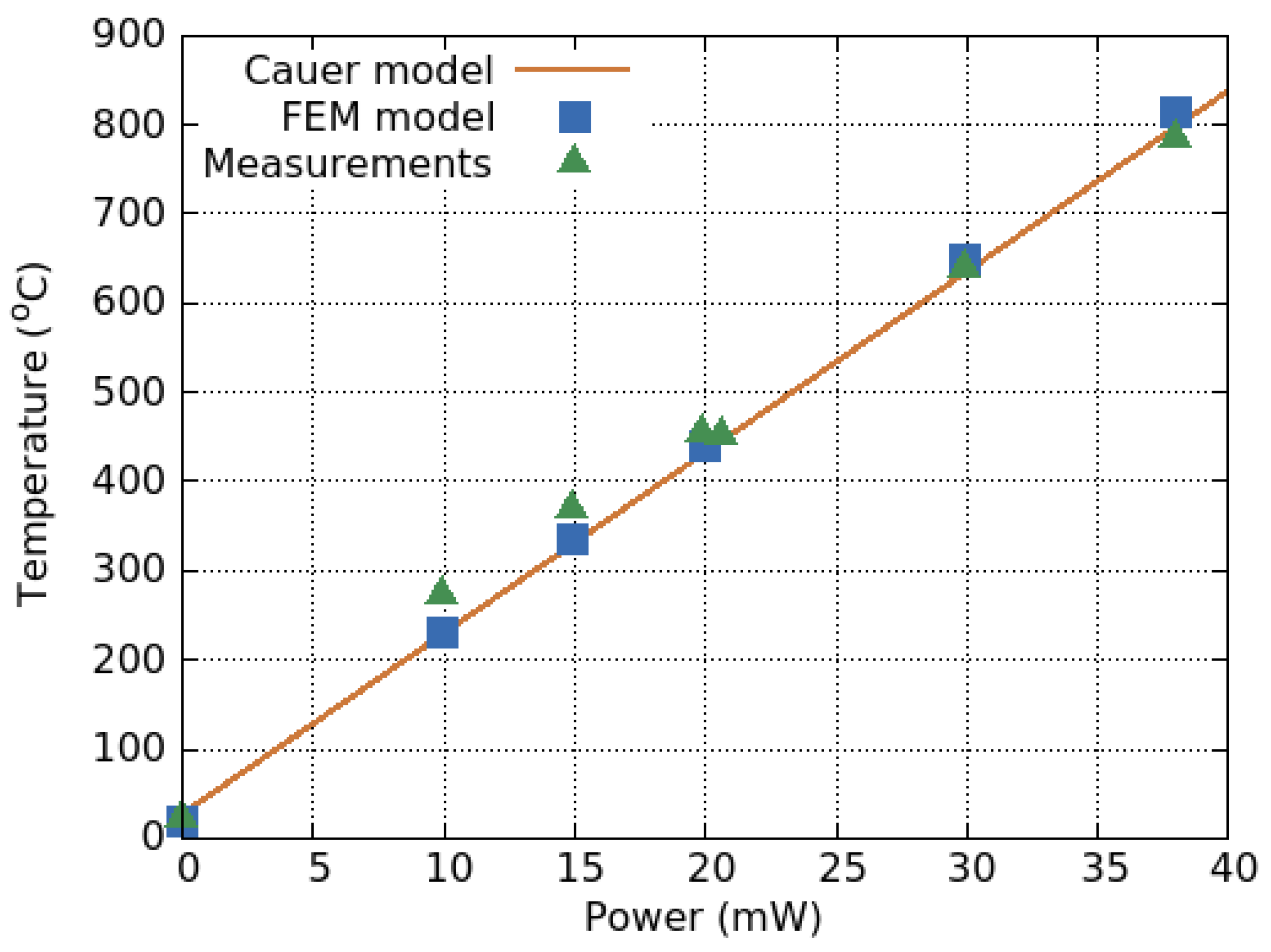

- Lahlalia, A.; Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Modeling and simulation of novel semiconducting metal oxide gas sensors for wearable devices. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlalia, A.; Le Neel, O.; Shankar, R.; Kam, S.Y.; Filipovic, L. Electro-thermal simulation & characterization of a microheater for SMO gas sensors. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2018, 27, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder, T.; Sagalowicz, L.; Muralt, P. Stabilized platinum electrodes for ferroelectric film deposition using Ti, Ta and Zr adhesion layers. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 37, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.G.; Holmen, J.O.; Foster, R.B.; Sridhar, U. Adhesion Layer for Platinum Based Sensors. U.S. Patent No. 4,952,904, 28 August 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Klemenschits, X.; Selberherr, S.; Filipovic, L. Modeling of gate stack patterning for advanced technology nodes: A review. Micromachines 2018, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhou, H.J.; Jin, Z.L.; Savinell, R.F.; Liu, C.C. Application of nano-crystalline porous tin oxide thin film for CO sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1998, 52, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.W.; Park, B.S.; Akbar, S.A.; Lee, W.S.; Hong, K.J.; Seo, Y.J.; Shin, D.C.; Park, J.S.; Choi, G.P. ZnO sol–gel derived porous film for CO gas sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2003, 96, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Hu, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Qin, Y. NO2-sensing properties of porous WO3 gas sensor based on anodized sputtered tungsten thin film. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 161, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinati, G.; Brunet, E.; Steinhauer, S.; Köck, A.; Teva, J.; Kraft, J.; Siegert, J.; Schrank, F.; Bertagnolli, E. CMOS-integrable ultrathin SnO2 layer for smart gas sensor devices. Procedia Eng. 2012, 47, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W. A Au-functionalized ZnO nanowire gas sensor for detection of benzene and toluene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17179–17186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sun, G.J.; Jin, C.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, C. Synergistic effects of a combination of Cr2O3-functionalization and UV-irradiation techniques on the ethanol gas sensing performance of ZnO nanorod gas sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 2805–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhushner, M.A.; Trakhtenberg, L.I.; Landerville, A.C.; Oleynik, I.I. Theory of sensing response of nanostructured tin-dioxide thin films to reducing hydrogen gas. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 11562–11568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, B.; Hu, J.; Qin, H.; Jiang, M. Semiconducting gas sensor for ethanol based on LaMgxFe1-xO3 nanocrystals. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 129, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Park, J.A.; Lee, S.J.; Zyung, T.; Kim, I.D. Pd-doped TiO2 nanofiber networks for gas sensor applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 149, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, P.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Shimanoe, K.; Yamazoe, N.; Lu, G. Highly sensitive acetone gas sensor based on porous ZnFe2O4 nanospheres. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 206, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Gou, X. α-Fe2O3 nanotubes in gas sensor and lithium-ion battery applications. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Zhan, J. Fabrication and gas-sensing properties of porous ZnO nanoplates. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4547–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, G.; Bonavita, A.; Micali, G.; Rizzo, G.; Callone, E.; Carturan, G. Resistive CO gas sensors based on In2O3 and InSnOx nanopowders synthesized via starch-aided sol–gel process for automotive applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 132, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, P.; Kneer, J.; Knobelspies, S.; Kronast, W.; Mescheder, U.; Palzer, S. Micromachined hotplate platform for the investigation of ink-jet printed, functionalized metal oxide nanoparticles. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2015, 24, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, I.; Bârsan, N.; Bauer, M.; Weimar, U. Micromachined metal oxide gas sensors: Opportunities to improve sensor performance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 73, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frietsch, M.; Zudock, F.; Goschnick, J.; Bruns, M. CuO catalytic membrane as selectivity trimmer for metal oxide gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2000, 65, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annanouch, F.; Gràcia, I.; Figueras, E.; Llobet, E.; Cané, C.; Vallejos, S. Localized aerosol-assisted CVD of nanomaterials for the fabrication of monolithic gas sensor microarrays. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 216, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Basu, S. Improved zinc oxide film for gas sensor applications. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2002, 25, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S.; Mutinati, G.C.; Brunet, E.; Steinhauer, S.; Köck, A.; Teva, J.; Kraft, J.; Siegert, J.; Schrank, F.; et al. Modeling the growth of tin dioxide using spray pyrolysis deposition for gas sensor applications. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2014, 27, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, E.; Maier, T.; Mutinati, G.; Steinhauer, S.; Köck, A.; Gspan, C.; Grogger, W. Comparison of the gas sensing performance of SnO2 thin film and SnO2 nanowire sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 165, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, G. First fifty years of chemoresistive gas sensors. Chemosensors 2015, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Yu, B.; Deng, P.; Xing, L.; Xue, X. High and fast H2S response of NiO/ZnO nanowire nanogenerator as a self-powered gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, E.; Meyyappan, M.; Nalwa, H.S. Flexible graphene-based wearable gas and chemical sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 34544–34586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eranna, G.; Joshi, B.; Runthala, D.; Gupta, R. Oxide materials for development of integrated gas sensors—A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 29, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G. Metal oxides for solid-state gas sensors: What determines our choice? Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2007, 139, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A. Semiconductor metal oxide gas sensors: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2018, 229, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, L.; Lahlalia, A. System-on-chip SMO gas sensor integration in advanced CMOS technology. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, B862–B879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Hu, S.; Zhang, D.; Ning, H. A survey on gas sensing technology. Sensors 2012, 12, 9635–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, A.; Baratto, C.; Cattabiani, N.; Falasconi, M.; Galstyan, V.; Nunez-Carmona, E.; Rigoni, F.; Sberveglieri, V.; Zambotti, G.; Zappa, D. Metal oxide gas sensors, a survey of selectivity issues addressed at the SENSOR Lab, Brescia (Italy). Sensors 2017, 17, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, B.T.; Vetelino, J.F. A semiconducting metal oxide sensor array for the detection of NOx and NH3. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 77, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Okawa, Y.; Tajima, M.; Nakai, T.; Yoshiike, N.; Natukawa, K. Micro-machined gas sensor array based on metal film micro-heater. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 79, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsan, N.; Koziej, D.; Weimar, U. Metal oxide-based gas sensor research: How to? Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 121, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.T.; Boussaid, F.; Bermak, A. A CMOS single-chip gas recognition circuit for metal oxide gas sensor arrays. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2011, 58, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konduru, T.; Rains, G.C.; Li, C. A customized metal oxide semiconductor-based gas sensor array for onion quality evaluation: System development and characterization. Sensors 2015, 15, 1252–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Hayasaka, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Oliveira, O.N.; Lin, L. A review on chemiresistive room temperature gas sensors based on metal oxide nanostructures, graphene and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Jiang, C.; Liu, A.; Xia, B. Quantitative detection of formaldehyde and ammonia gas via metal oxide-modified graphene-based sensor array combining with neural network model. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 240, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo Lee, S.; ping Tsai, P.; Chen, H. H2 sensing behavior of MOCVD-derived SnO2 thin films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1997, 41, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsan, N.; Rebholz, J.; Weimar, U. Conduction mechanism switch for SnO2 based sensors during operation in application relevant conditions; implications for modeling of sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 207, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Brinzari, V.; Pronin, I.; Ham, M.; Cho, B. Metal oxides for application in conductometric gas sensors: How to choose. In Solid State Phenomena; Trans Tech Publications: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 266, pp. 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.W.; Guha, P.K.; Udrea, F.; Covington, J.A. CMOS interfacing for integrated gas sensors: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2010, 10, 1833–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.H.; Cho, I.; Kang, K.; Kweon, S.J.; Lee, M.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, I. Fully integrated and portable semiconductor-type multi-gas sensing module for IoT applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 265, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattain, W.H.; Bardeen, J. Surface properties of germanium. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1953, 32, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiyama, T.; Kato, A.; Fujiishi, K.; Nagatani, M. A new detector for gaseous components using semiconductive thin films. Anal. Chem. 1962, 34, 1502–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P.J. Activated tungsten oxide gas detectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1967, 11, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ams AG. Ultra-Low Power Analog VOC Sensor for Indoor Air Quality Monitoring, CCS801:v1-02. 23 April 2016. Available online: https://ams.com/documents/20143/36005/CCS801_DS000457_3-00.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- ams AG. Air Quality Sensor, AS-MLV-P2:v1-01. 12 October 2015. Available online: https://ams.com/documents/20143/36005/AS-MLV-P2_DS000359_1-00.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- ams AG. Ultra-Low Power Digital Gas Sensor for Monitoring Indoor Air Quality, CCS811:v1-00. 7 February 2019. Available online: https://ams.com/documents/20143/36005/CCS811_DS000459_7-00.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Figaro USA, Inc. TGS 2600—For the Detection of Air Contaminants. September 2013. Available online: http://www.figarosensor.com/product/entry/tgs2600.html (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Figaro USA, Inc. TGS 2602—For the Detection of Air Contaminants. June 2015. Available online: http://www.figarosensor.com/product/entry/tgs2602.html (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Figaro USA, Inc. TGS 8100—For the Detection of Air Contaminants. September 2014. Available online: http://www.figarosensor.com/product/entry/tgs8100.html (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Taguchi, N. Gas-Detecting Device. U.S. Patent No. 3,695,848, 3 October 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. Gas-detecting device. U.S. Patent No. 3,631,436, 28 December 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Velmathi, G.; Mohan, S.; Henry, R. Analysis and review of tin oxide-based chemoresistive gas sensor. IETE Tech. Rev. 2016, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, E.; Krainer, J.; Wimmer-Teubenbacher, R.; Sosada, F.; Deluca, M.; Gspan, C.; Rohracher, K.; Wachmann, E.; Köck, A. Carbon monoxide detection with CMOS integrated thin film SnO2 gas sensor. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 7128–7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

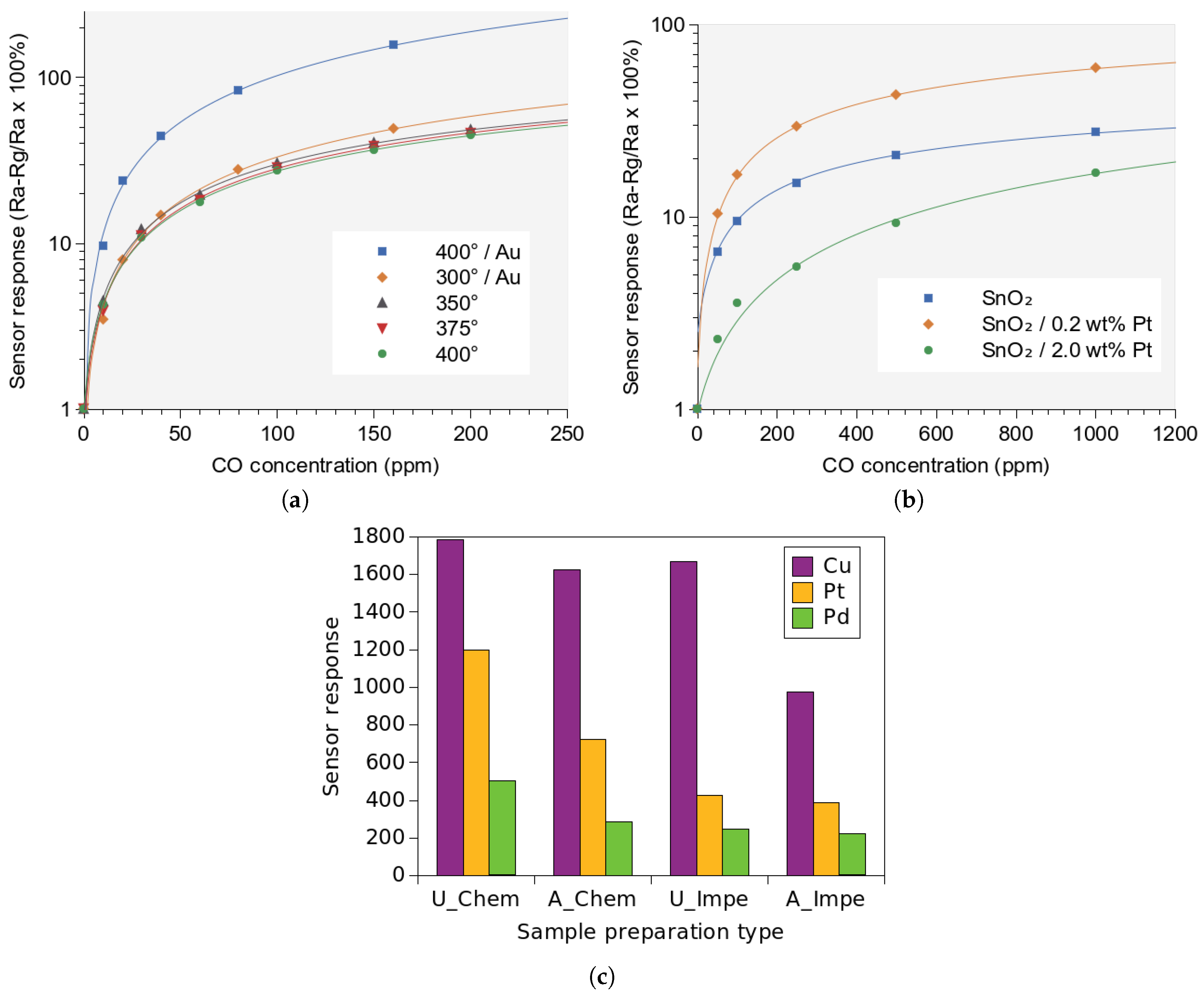

- Wimmer-Teubenbacher, R.; Steinhauer, S.; von Sicard, O.; Magori, E.; Siegert, J.; Rohracher, K.; Gspan, C.; Grogger, W.; Köck, A. Gas sensing characterisation of CMOS integrated nanocrystalline SnO2–Au thin films. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 4295–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Performance and stress analysis of metal oxide films for CMOS-integrated gas sensors. Sensors 2015, 15, 7206–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mädler, L.; Sahm, T.; Gurlo, A.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Barsan, N.; Weimar, U.; Pratsinis, S.E. Sensing low concentrations of CO using flame-spray-made Pt/SnO2 nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2006, 8, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, V.; Gómez-Pozos, H.; Rodríguez-Lugo, V.; Olvera, M. A study of the CO sensing responses of Cu-, Pt- and Pd-activated SnO2 sensors: Effect of precipitation agents, dopants and doping methods. Sensors 2017, 17, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degler, D. Spectroscopic Insights in the Gas Detection Mechanism of tin Dioxide Based Gas Sensors. Ph.D. Thesis, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degler, D.; Müller, S.A.; Doronkin, D.E.; Wang, D.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Platinum loaded tin dioxide: A model system for unravelling the interplay between heterogeneous catalysis and gas sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 2034–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.A.; Degler, D.; Feldmann, C.; Türk, M.; Moos, R.; Fink, K.; Studt, F.; Gerthsen, D.; Bârsan, N.; Grunwaldt, J.D. Exploiting synergies in catalysis and gas sensing using noble metal-loaded oxide composites. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 864–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Stress considerations for system-on-chip gas sensor integration in CMOS technology. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2016, 16, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, I.; Zampolli, S.; Cozzani, E.; Mancarella, F.; Cardinali, G. Development of ultra-low-power consumption MOX sensors with ppb-level VOC detection capabilities for emerging applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 135, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Processing of integrated gas sensor devices. In Proceedings of the TENCON—2015 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Macau, China, 1–4 November 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenović, B.; Radmilović-Radjenović, M. 3D simulations of the profile evolution during anisotropic wet etching of silicon. Thin Solid Film. 2009, 517, 4233–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Jun Belen, R.; Kiehlbauch, M.; Aydil, E.S. Etching of high aspect ratio structures in Si using SF6/O2 plasma. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2004, 22, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen, R.J.; Gomez, S.; Kiehlbauch, M.; Cooperberg, D.; Aydil, E.S. Feature-scale model of Si etching in SF6 plasma and comparison with experiments. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vacuum, Surf. Film 2005, 23, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Microelectronics, TU Wien. ViennaTS, the Vienna Topography Simulator. Available online: http://www.iue.tuwien.ac.at/software/viennats/ (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Seele, S. Stress and Structure Evolution during Volmer-Weber Growth of Thin Films. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. Available online: http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/29912 (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Stress considerations in thin films for CMOS-integrated gas sensors. ECS Trans. 2015, 66, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, H.M.; Tse, M.S.; Chiu, M.M. Thermal induced stress on the membrane in integrated gas sensor with micro-heater. In Proceedings of the 1998 Hong Kong Electron Devices Meeting (Cat. No. 98TH8368), Hong Kong, China, 29 August 1998; pp. 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppeta, R.; Lahlalia, A.; Kozic, D.; Hammer, R.; Riedler, J.; Toschkoff, G.; Singulani, A.; Ali, Z.; Sagmeister, M.; Carniello, S.; et al. Electro-thermal-mechanical modeling of gas sensor hotplates. In Sensor Systems Simulations; van Driel, W.D., Pyper, O., Schumann, C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; Chapter 2; pp. 17–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Dyer, D.; Gardner, J. Design and optimisation of a high-temperature silicon micro-hotplate for nanoporous palladium pellistors. Microelectron. J. 2003, 34, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, R.G.; van Omme, J.T.; Ghatkesar, M.K.; Garza, H.H.P. A Review on development and optimization of microheaters for high-temperature in situ studies. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2017, 26, 1165–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridi, A.; Ruan, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M. Residual stresses in thin film systems: Effects of lattice mismatch, thermal mismatch and interface dislocations. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013, 50, 3562–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Chung, W.Y.; Choi, M.S.; Baek, J.M. Low-power micro gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1996, 33, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatthanakun, R.; Deekla, P.; Pummara, W.; Sriphung, C.; Pantong, C.; Chomnawang, N. Fabrication and control of thin-film aluminum microheater and nickel temperature sensor. In Proceedings of the 8th Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI) Association of Thailand-Conference 2011, Khon Kaen, Thailand, 17–19 May 2011; pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chou, S.; Ang, S. Fabrication, modeling and testing of a thin film Au/Ti microheater. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2007, 46, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, T.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. Development of a reliable micro-hotplate with low power consumption. IEEE Sens. J. 2010, 11, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Basu, P.; Mondal, B.; Saha, H. A low power MEMS gas sensor based on nanocrystalline ZnO thin films for sensing methane. Microelectron. Reliab. 2008, 48, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibbern, U. A substrate for thin-film gas sensors in microelectronic technology. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1990, 2, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, I.; Burzo, M.; Ali, S.; Komarov, P.; Udrea, F.; Raad, P. Thermal characterization of SOI CMOS micro hot-plate gas sensors. In Proceedings of the 2010 16th International Workshop on Thermal Investigations of ICs and Systems (THERMINIC), Barcelona, Spain, 6–8 October 2010; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5636330 (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Ali, S.Z.; Udrea, F.; Milne, W.I.; Gardner, J.W. Tungsten-based SOI microhotplates for smart gas sensors. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2008, 17, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, H.; Kuang, Y.; Du, L.; Guo, J. Nickel membrane temperature sensor in micro-flow measurement. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 449, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika, D.; Arora, A. Design and simulation of MEMS based microhotplate as gas sensor. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2. Available online: http://ijarcet.org/wp-content/uploads/IJARCET-VOL-2-ISSUE-8-2487-2492.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Mele, L.; Santagata, F.; Iervolino, E.; Mihailovic, M.; Rossi, T.; Tran, A.; Schellevis, H.; Creemer, J.; Sarro, P. A molybdenum MEMS microhotplate for high-temperature operation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2012, 188, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.; Dinh, T.; Phan, H.P.; Kozeki, T.; Namazu, T.; Dao, D.V.; Nguyen, N.T. Steady-state analytical model of suspended p-type 3C–SiC bridges under consideration of Joule heating. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2017, 27, 075008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemer, J.; Briand, D.; Zandbergen, H.; Van der Vlist, W.; De Boer, C.; de Rooij, N.F.; Sarro, P. Microhotplates with TiN heaters. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2008, 148, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, G.G.S. Design of a Silicon Carbide Micro-Hotplate Geometry for High Temperature Chemical Sensing. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/17535 (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Spannhake, J.; Schulz, O.; Helwig, A.; Krenkow, A.; Müller, G.; Doll, T. High-temperature MEMS heater platforms: Long-term performance of metal and semiconductor heater materials. Sensors 2006, 6, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.Z.; De Luca, A.; Hopper, R.; Boual, S.; Gardner, J.; Udrea, F. A low-power, low-cost infra-red emitter in CMOS technology. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 6775–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlalia, A.; Le Neel, O.; Shankar, R.; Selberherr, S.; Filipovic, L. Improved sensing capability of integrated semiconducting metal oxide gas sensor devices. Sensors 2019, 19, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegele, M.; Gamauf, C.; Nemecek, A.; Mutinati, G.C.; Steinhauer, S.; Köck, A.; Kraft, J.; Siezert, J.; Schrank, F. Optimized integrated micro-hotplates in CMOS technology. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 11th International New Circuits and Systems Conference (NEWCAS), Paris, France, 16–19 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çengel, Y.A.; Cimbala, J.M.; Turner, R.H. Fundamentals of Thermal-Fluid Sciences, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parameswaran, M.; Robinson, A.M.; Blackburn, D.L.; Gaitan, M.; Geist, J. Micromachined thermal radiation emitter from a commercial CMOS process. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1991, 12, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- März, M.; Nance, P. Thermal Modeling of Power Electronic Systems; Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS-B, Erlangen & Infineon Technologies AG: Munich, Germany, 2000; Available online: https://www.iisb.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/iisb2014/en/Documents/Research-Areas/Energy_Electronics/publications_patents_downloads/Publications/Therm_Modelling_2000_IISB.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Murthy, K.; Bedford, R. Transformation between Foster and Cauer equivalent networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 1978, 25, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulzer, G.; Baumgartner, S.; Brunet, E.; Mutinati, G.C.; Steinhauer, S.; Köck, A.; Barbano, P.E.; Heitzinger, C. Kinetic parameter estimation and fluctuation analysis of CO at SnO2 single nanowires. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 315501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, A.; Mugnaini, M.; Rocchi, S.; Serrano-Santos, M.B.; Vignoli, V.; Spinicci, R. Simplified models for SnO2 sensors during chemical and thermal transients in mixtures of inert, oxidizing and reducing gases. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 124, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degler, D.; Wicker, S.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Identifying the active oxygen species in SnO2 based gas sensing materials: An operando IR spectrsocopy study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 11792–11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, S. Influence of Humidity on the Gas Sensing Characteristics of SnO2: DRIFTS Investigation of Different Base Materials and Dopants. Ph.D. Thesis, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Tian, C.; Huang, D.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, C.; Tian, X.; Wang, M.; Li, E. Power-law response of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors to oxygen in presence of reducing gases. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 267, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y. A theoretical investigation of the power-law response of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors I: Schottky barrier control. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, M.; Li, E. A theoretical investigation of the power-law response of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors II: Size and shape effects. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 3541–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | SMO | Catalyic Pellistor | Piezo- Electric | Electro- Chemical | Thermal Pellistor | Photo- Ionization | Infrared Adsorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Accuracy | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Selectivity | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Response time | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Stability | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Durability | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Power | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Cost | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Footprint | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Material | CTE (10 K) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’S Ratio | Density (Mg/m) | Thermal Conductivity (W·mK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO | 0.55–0.75 | 66.3–74.8 | 0.15–0.19 | 2.17–2.65 | 1.3–1.5 |

| SiN | 1.4–3.7 | 166–297 | 0.23–0.28 | 2.37–3.25 | 10–43 |

| Si | 7–8 | 140–180 | 0.265–0.275 | 2.28–2.38 | 84–100 |

| Aluminum | 16–24 | 68–88.5 | 0.32–0.36 | 2.57–2.95 | 80–220 |

| Platinum | 8.8–9.2 | 154–172 | 0.385–0.395 | 21.45–21.47 | 70–72 |

| Tungsten | 4.2–4.6 | 340–410 | 0.27–0.29 | 19.25–19.35 | 170–175 |

| Thermal Parameter | Electrical Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Temperature (K) | Voltage (V) |

| Specific heat (J kg K) | Permittivity (F m) |

| Thermal resistivity (K m W) | Electrical resistivity ( m) |

| Thermal resistance (K W) | Resistance (V A) |

| Heat flow (W) | Current (A) |

| Heat (J = W s) | Charge (C = A s) |

| Thermal conductivity (W K m) | Electrical conductivity (S m) |

| Capacitance (J K) | Capacitance (F) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filipovic, L.; Selberherr, S. Thermo-Electro-Mechanical Simulation of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. Materials 2019, 12, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152410

Filipovic L, Selberherr S. Thermo-Electro-Mechanical Simulation of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. Materials. 2019; 12(15):2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152410

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilipovic, Lado, and Siegfried Selberherr. 2019. "Thermo-Electro-Mechanical Simulation of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Gas Sensors" Materials 12, no. 15: 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152410

APA StyleFilipovic, L., & Selberherr, S. (2019). Thermo-Electro-Mechanical Simulation of Semiconductor Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. Materials, 12(15), 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152410