Durability and Time-Dependent Properties of Low-Cement Concrete

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Significance

3. Experimental Program

3.1. Concrete Formulation

3.2. Workability and Mechanical Properties of Concrete

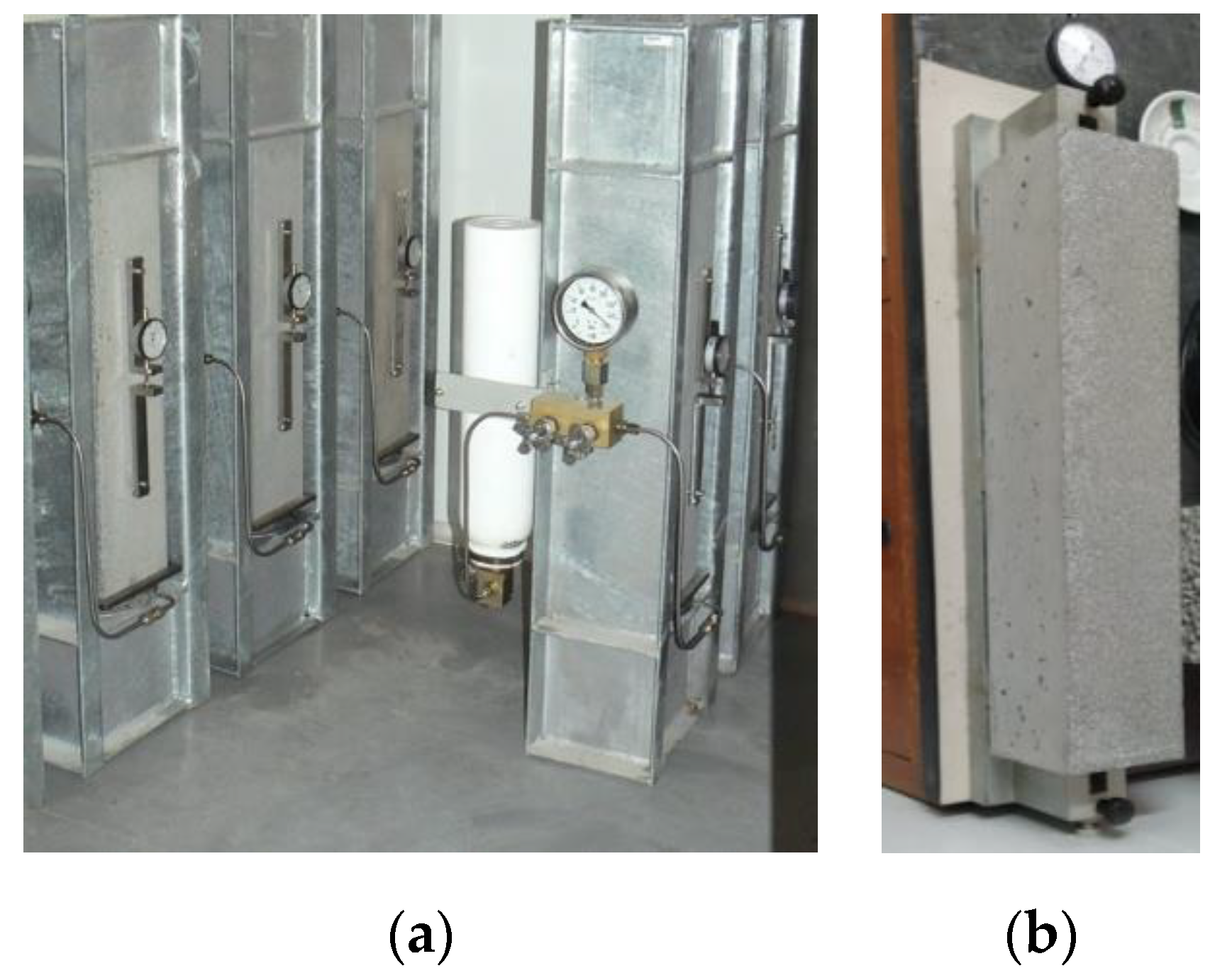

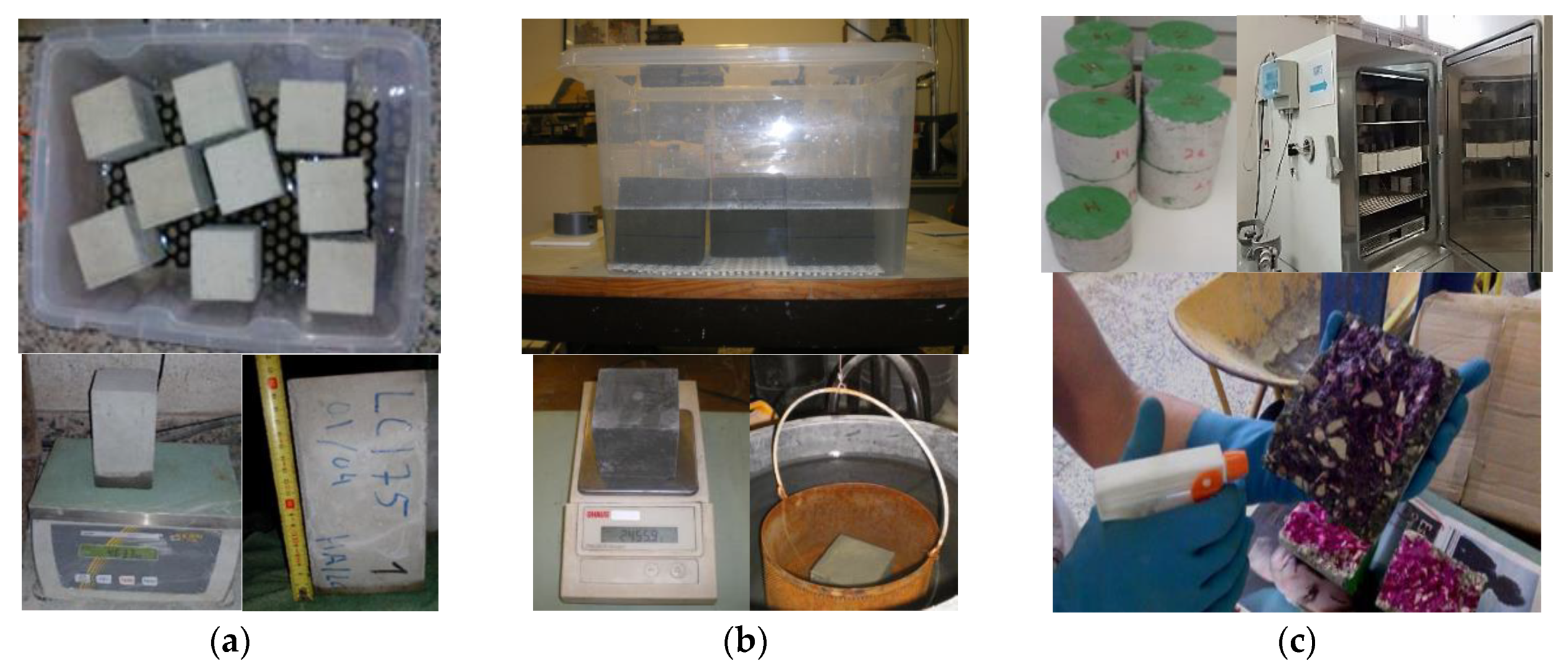

3.3. Durability and Time-Dependent Tests

4. Results and Discussion

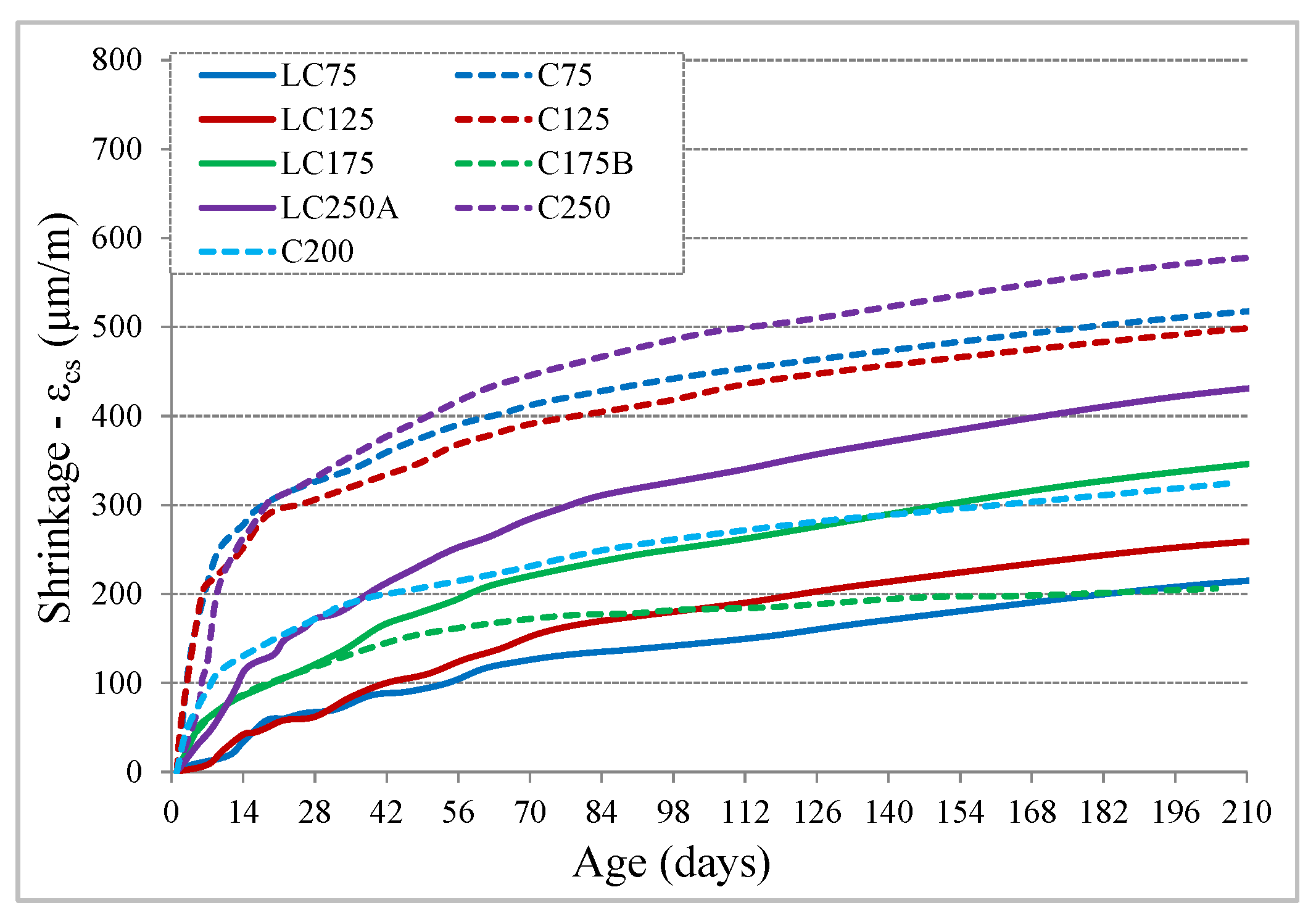

4.1. Shrinkage

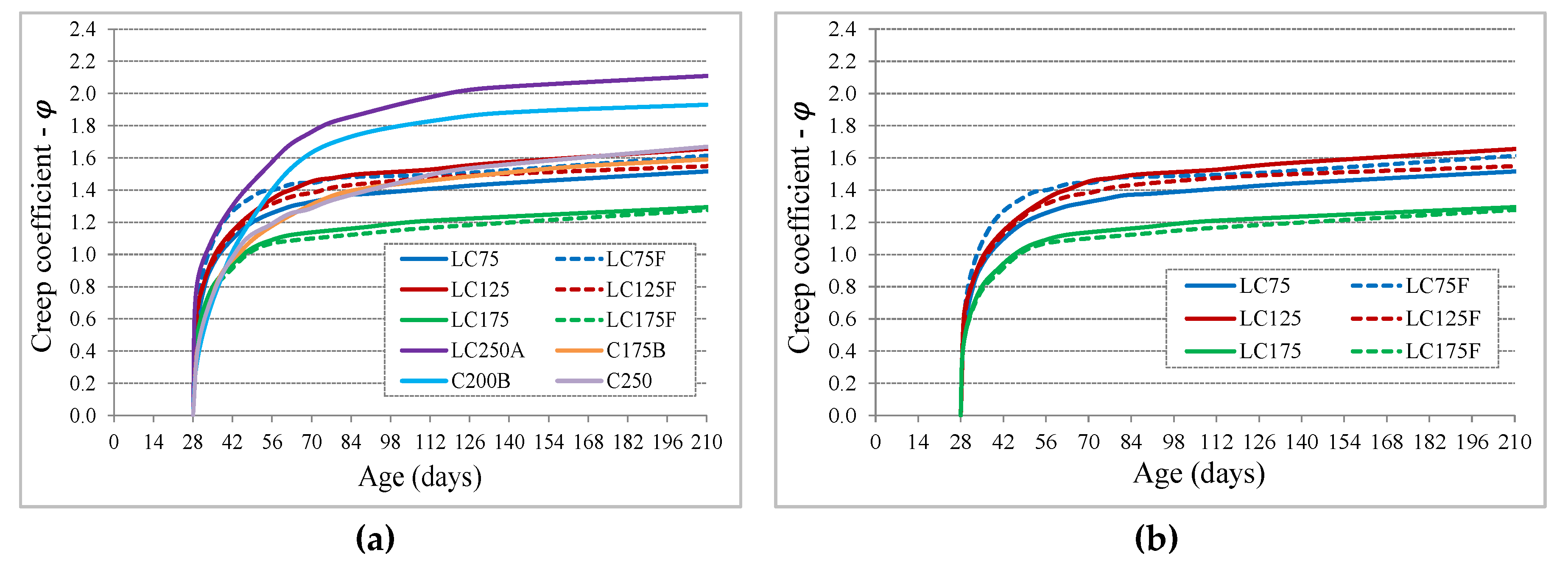

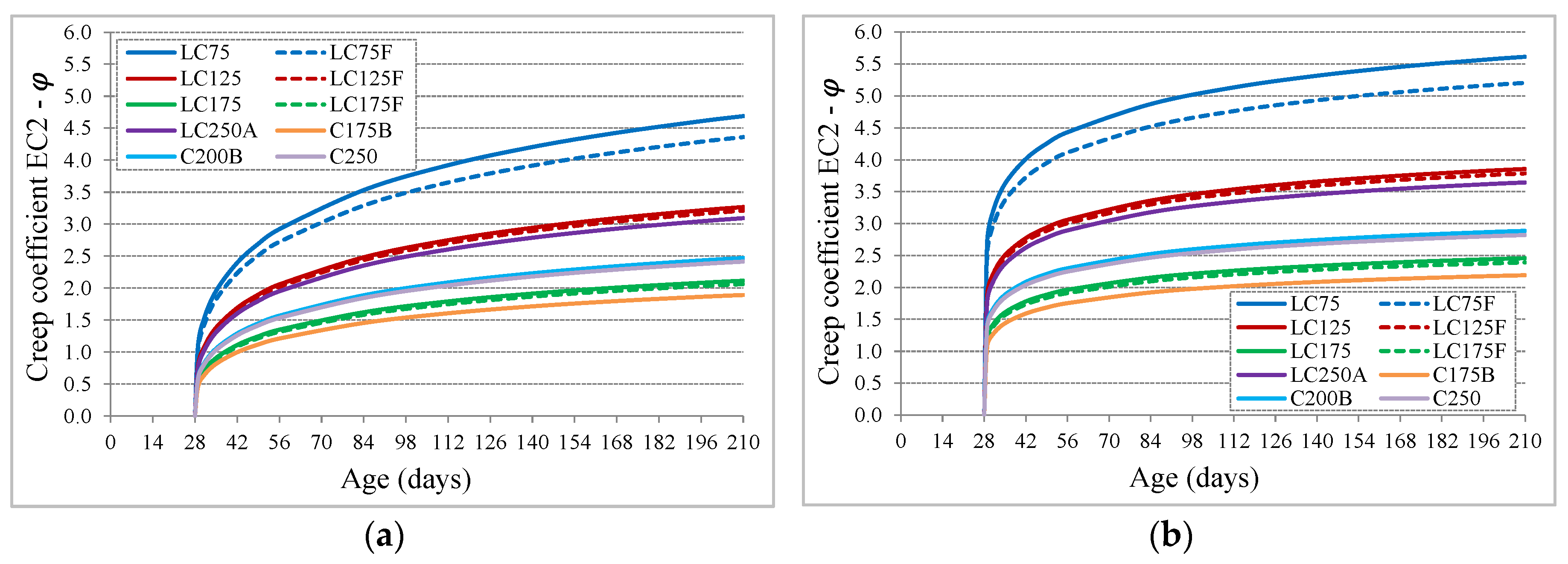

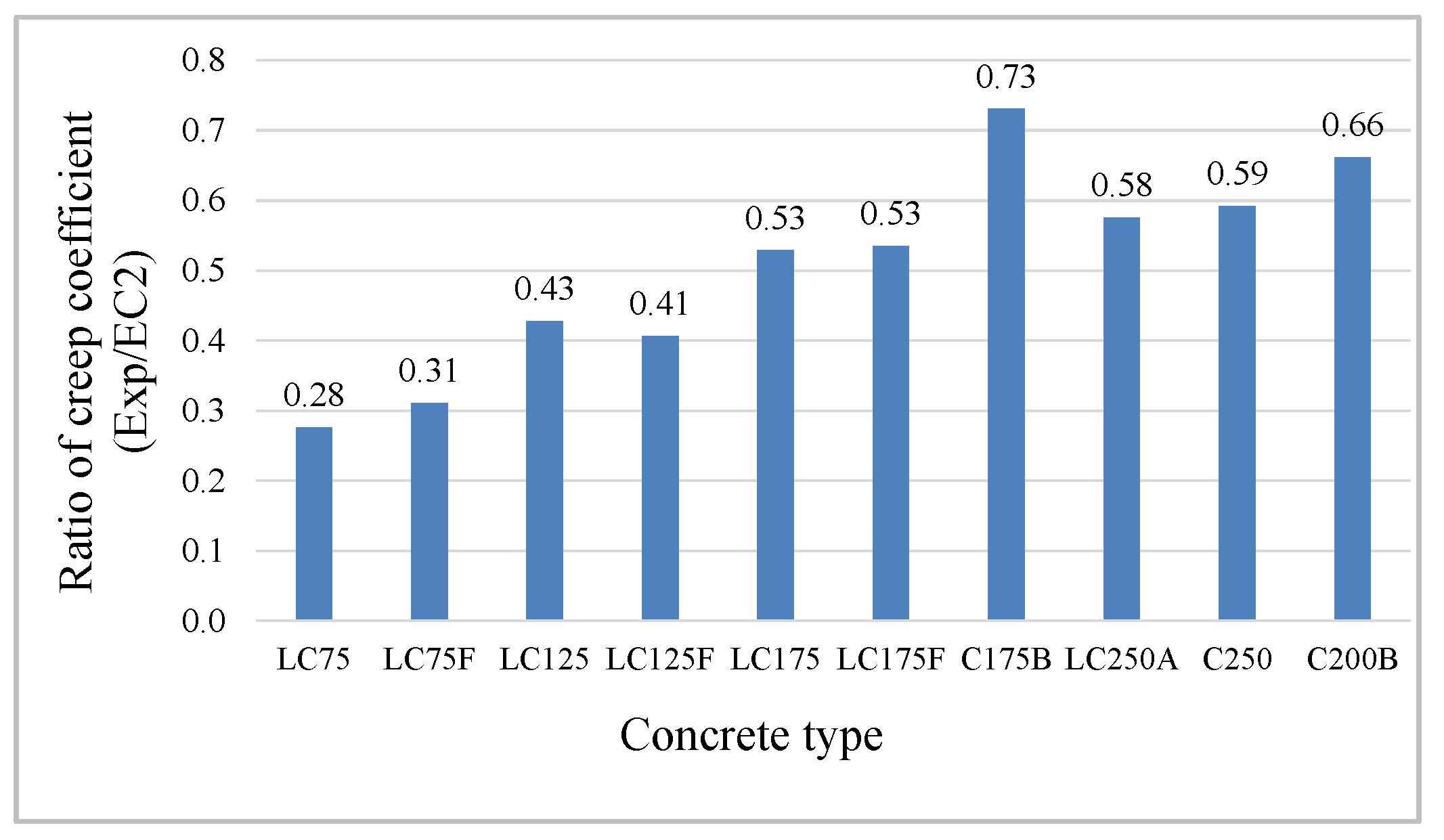

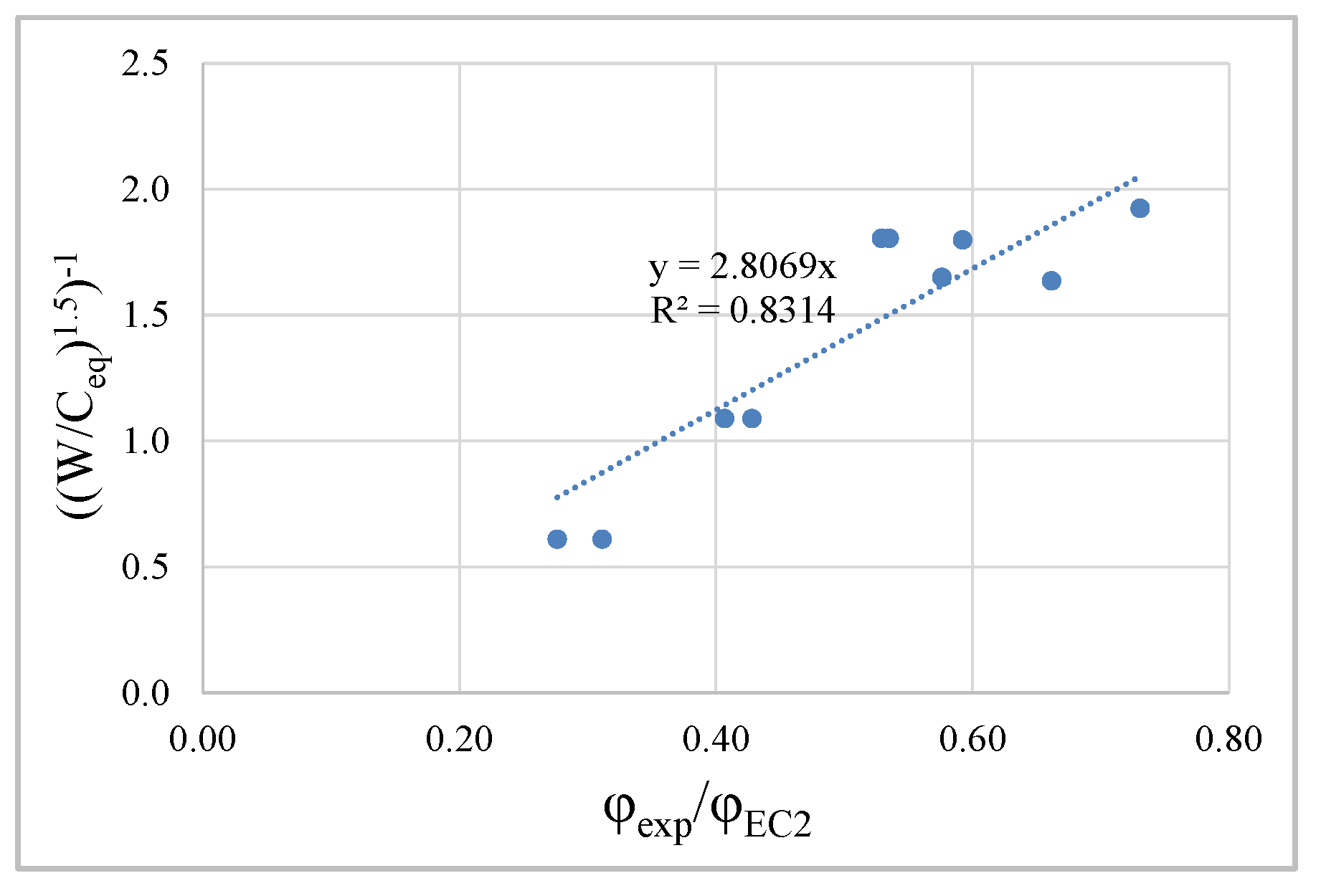

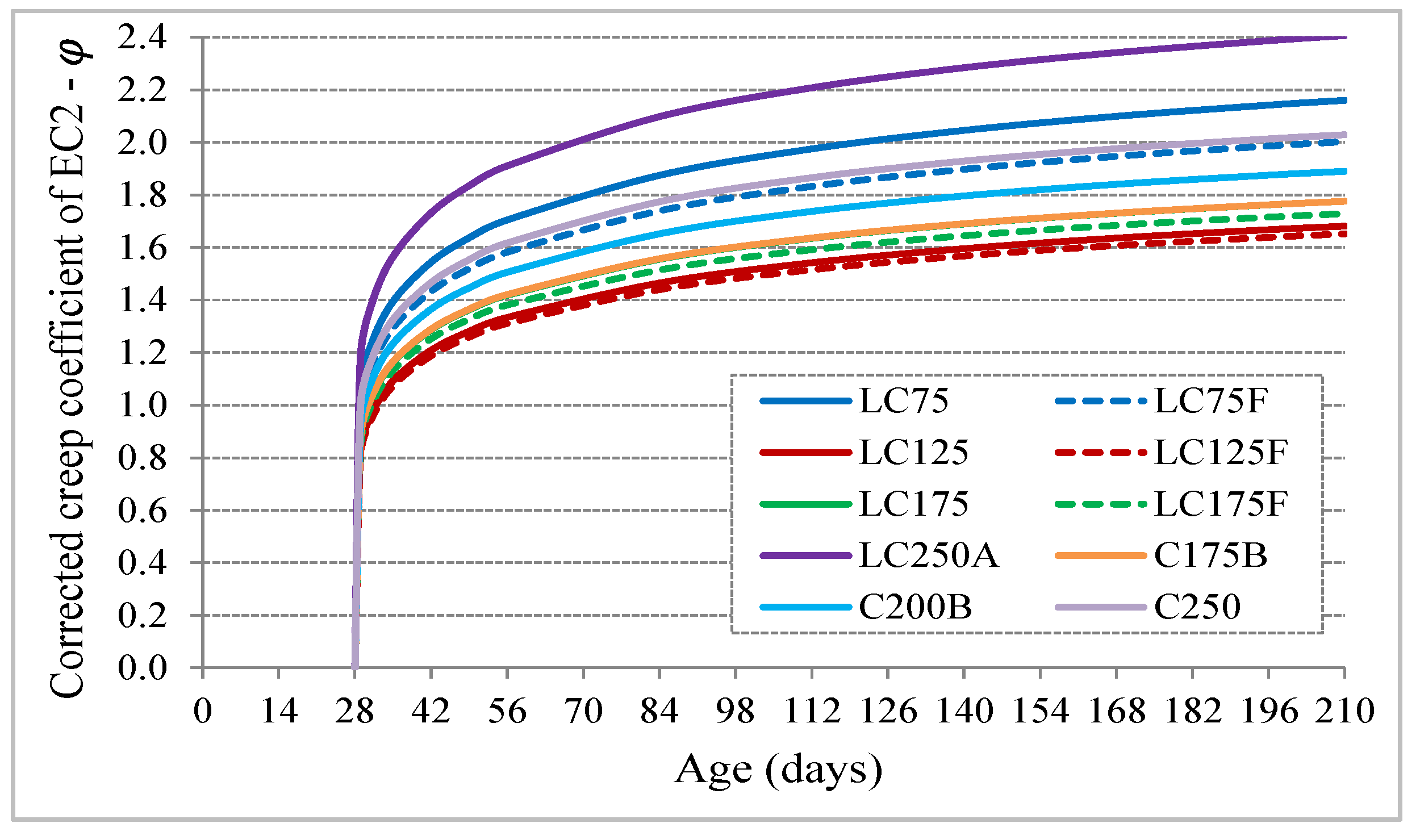

4.2. Creep

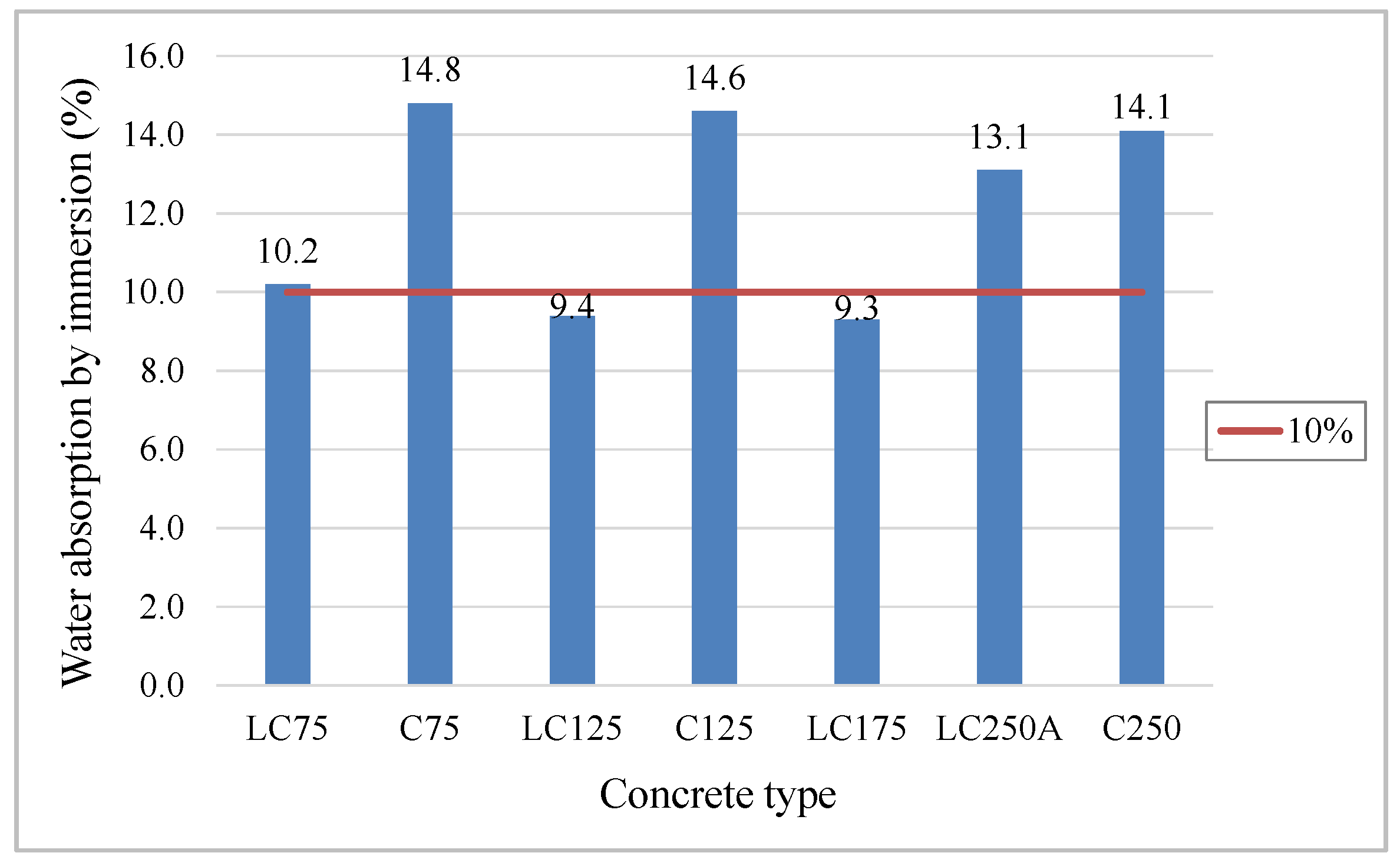

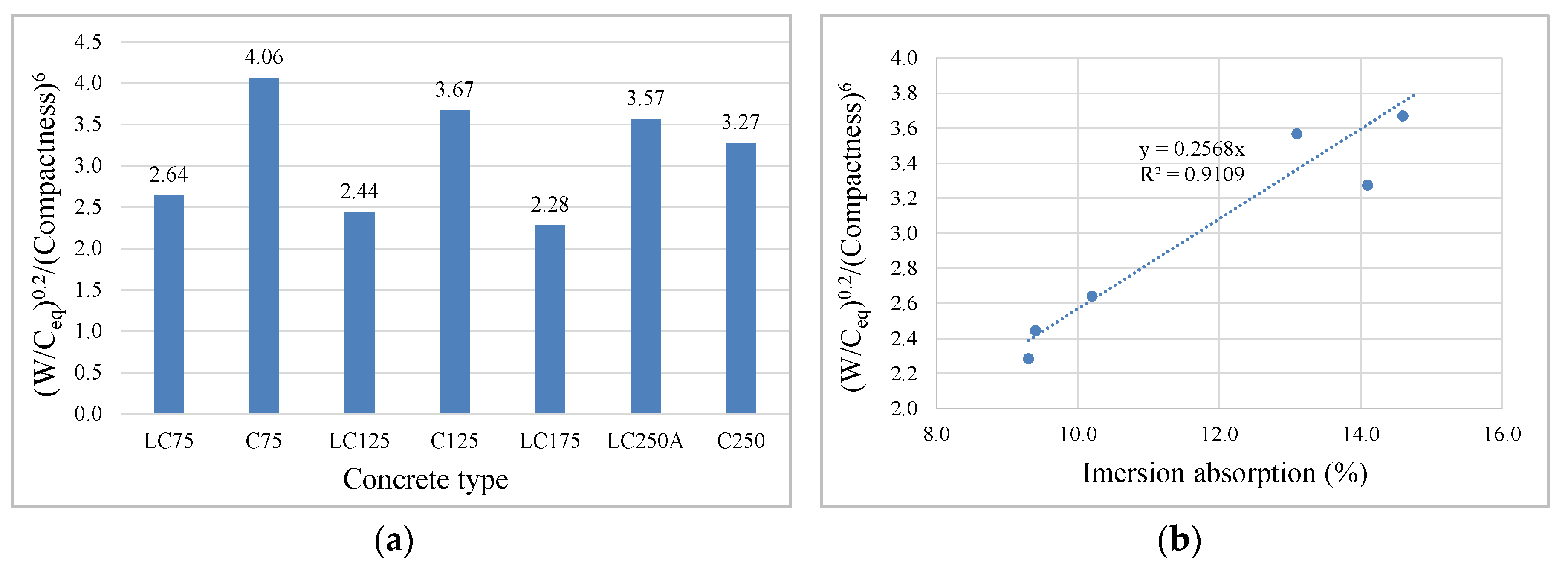

4.3. Water Absorption by Immersion

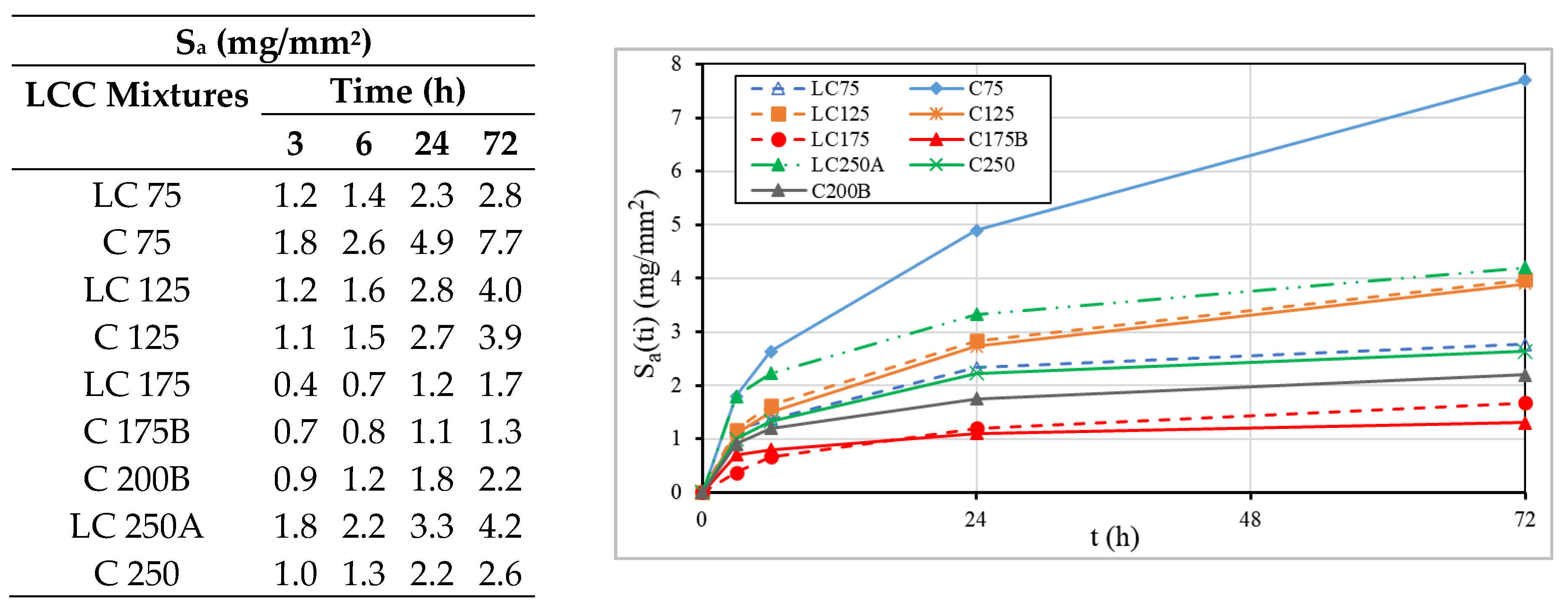

4.4. Capillary Water Absorption

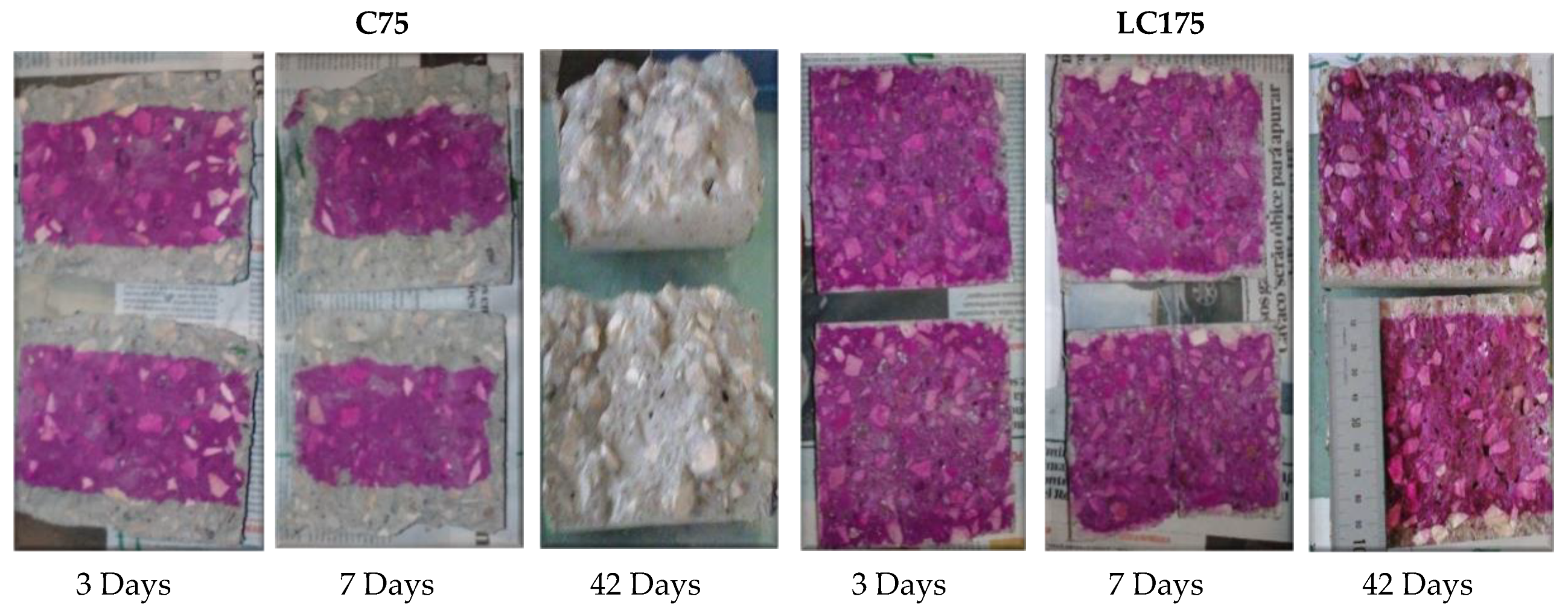

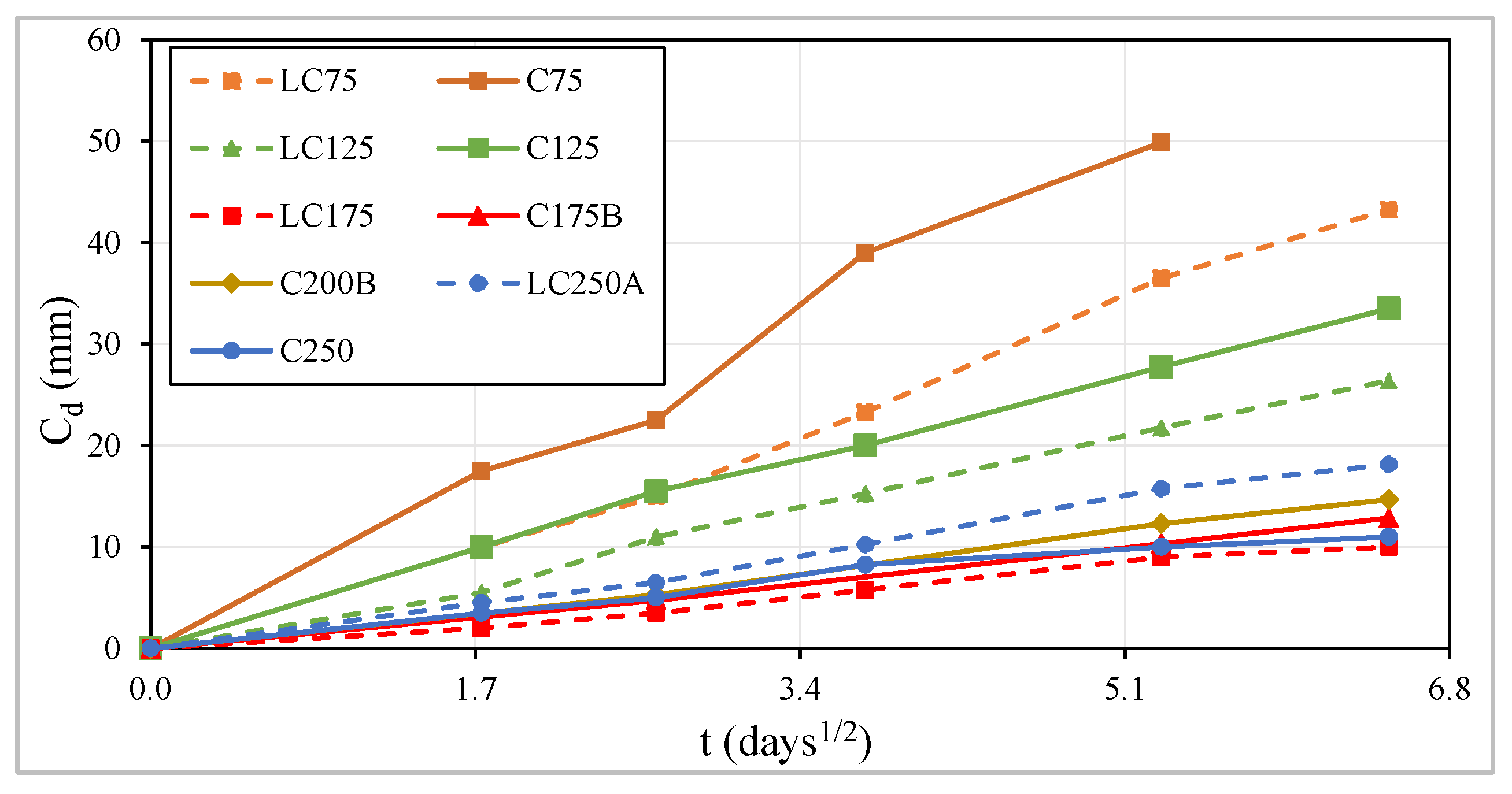

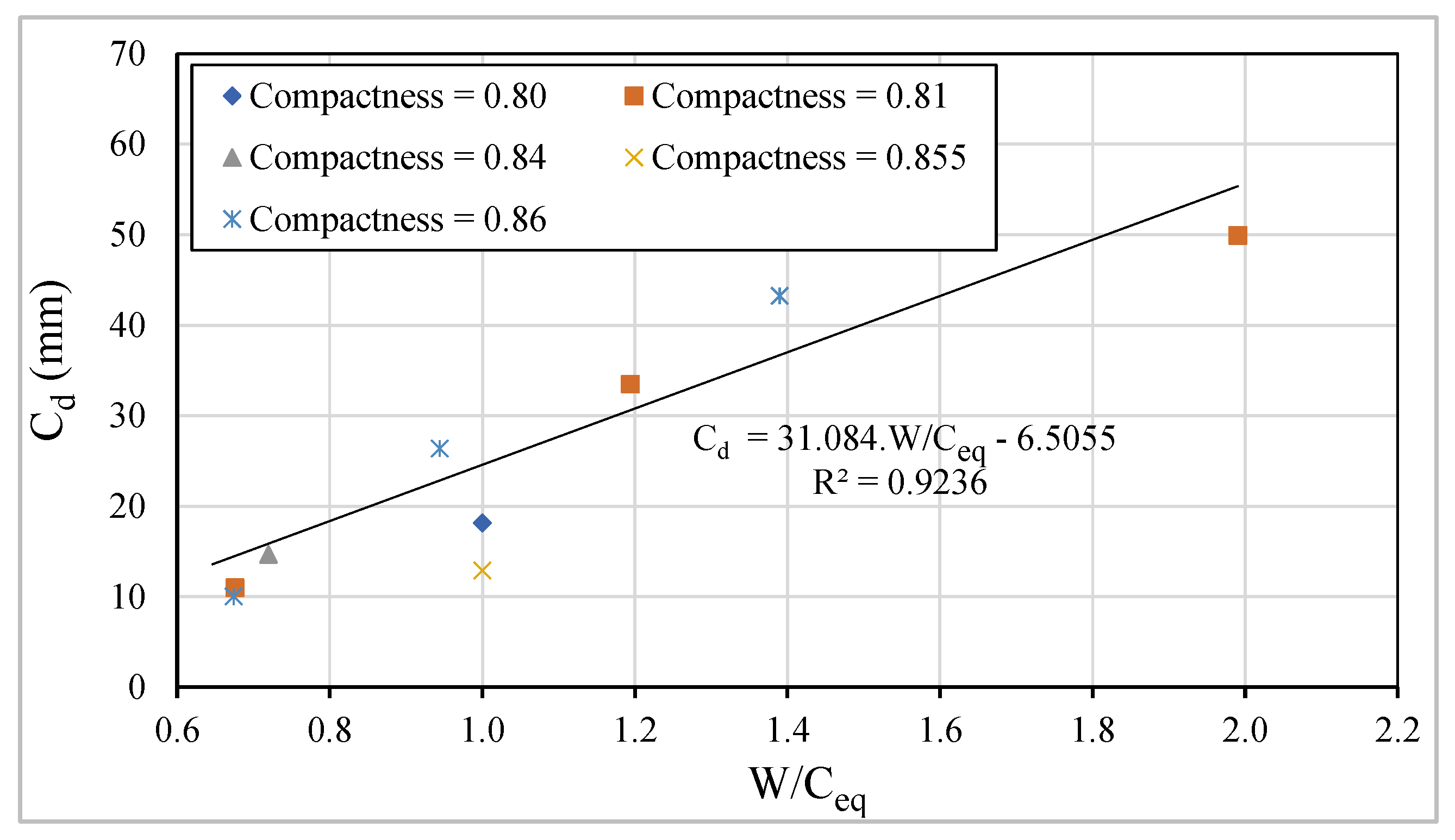

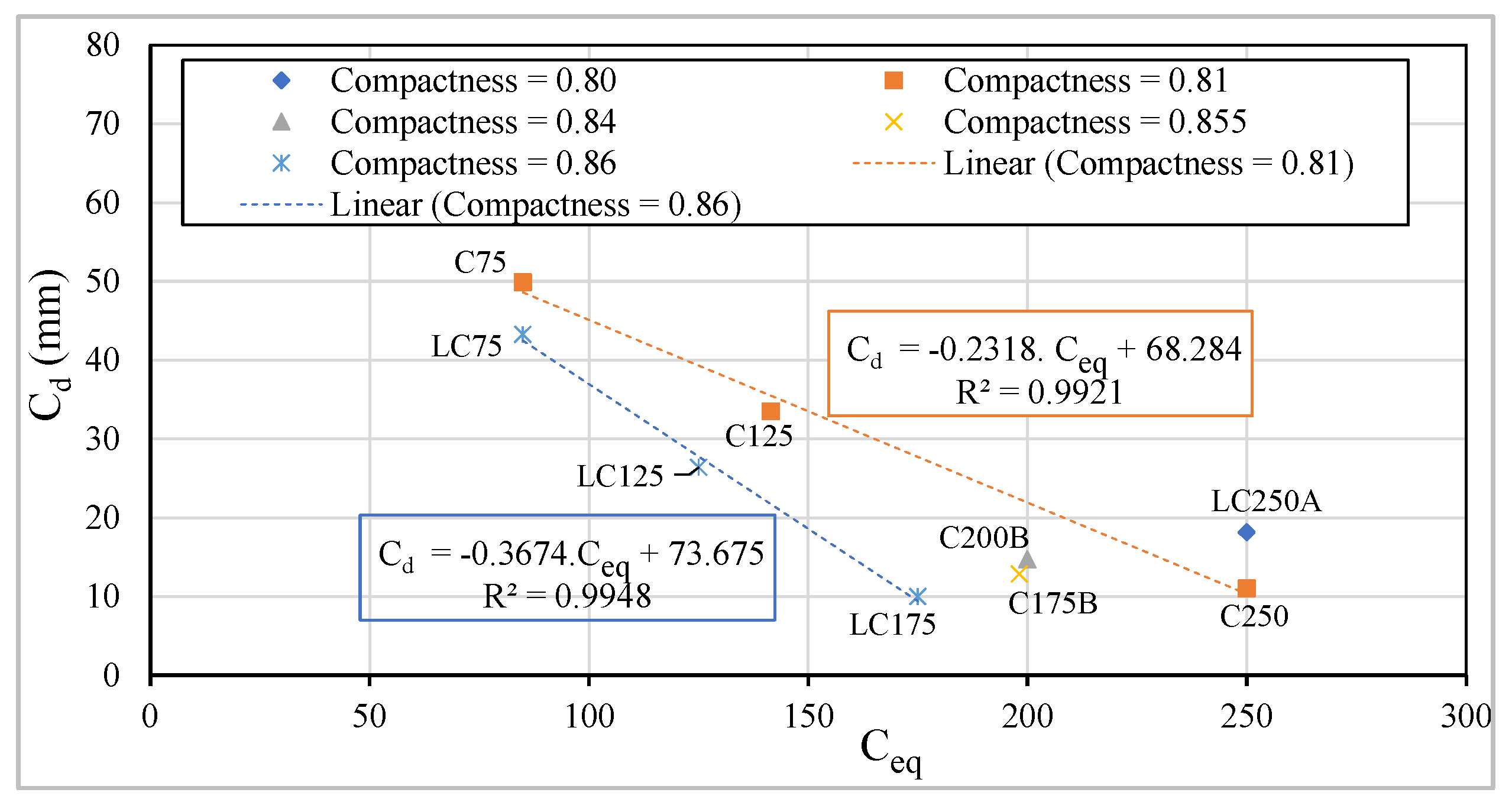

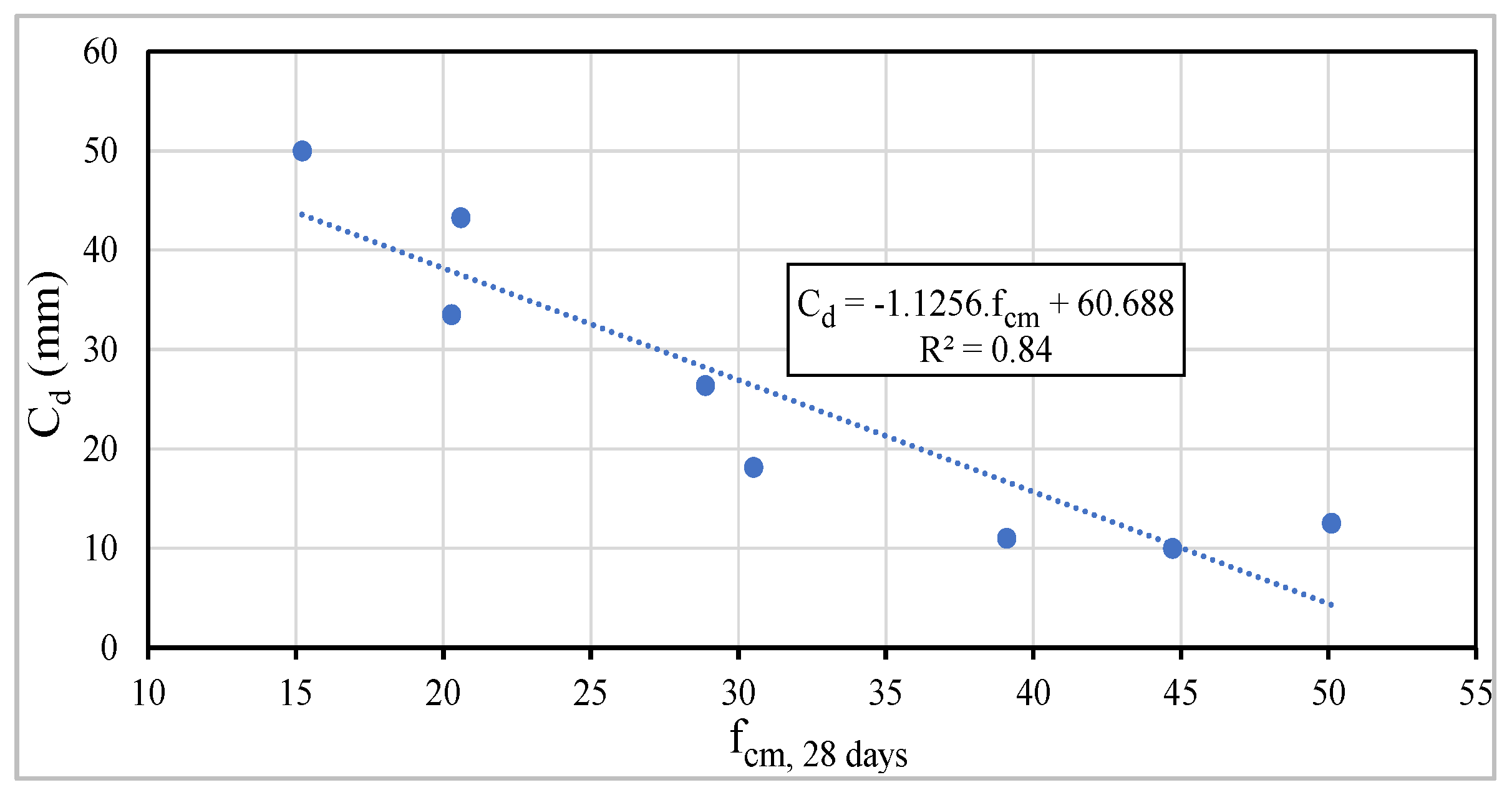

4.5. Carbonation

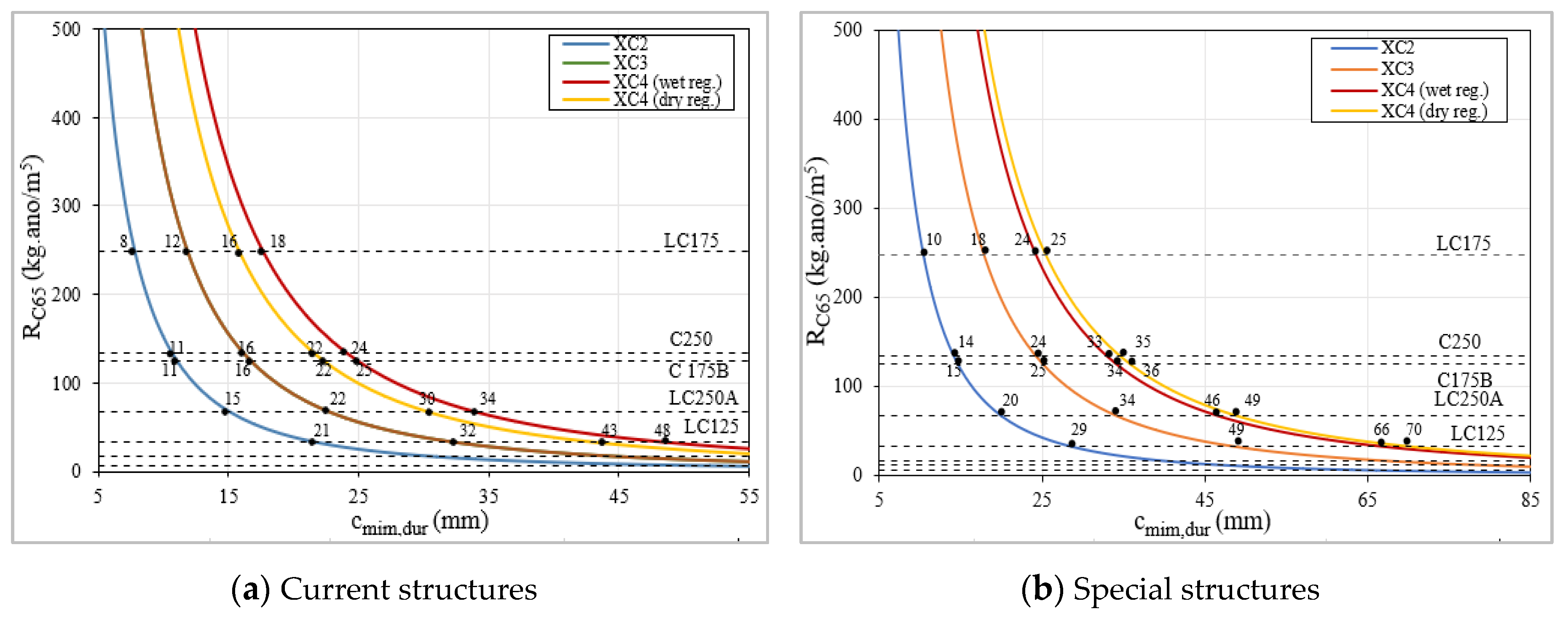

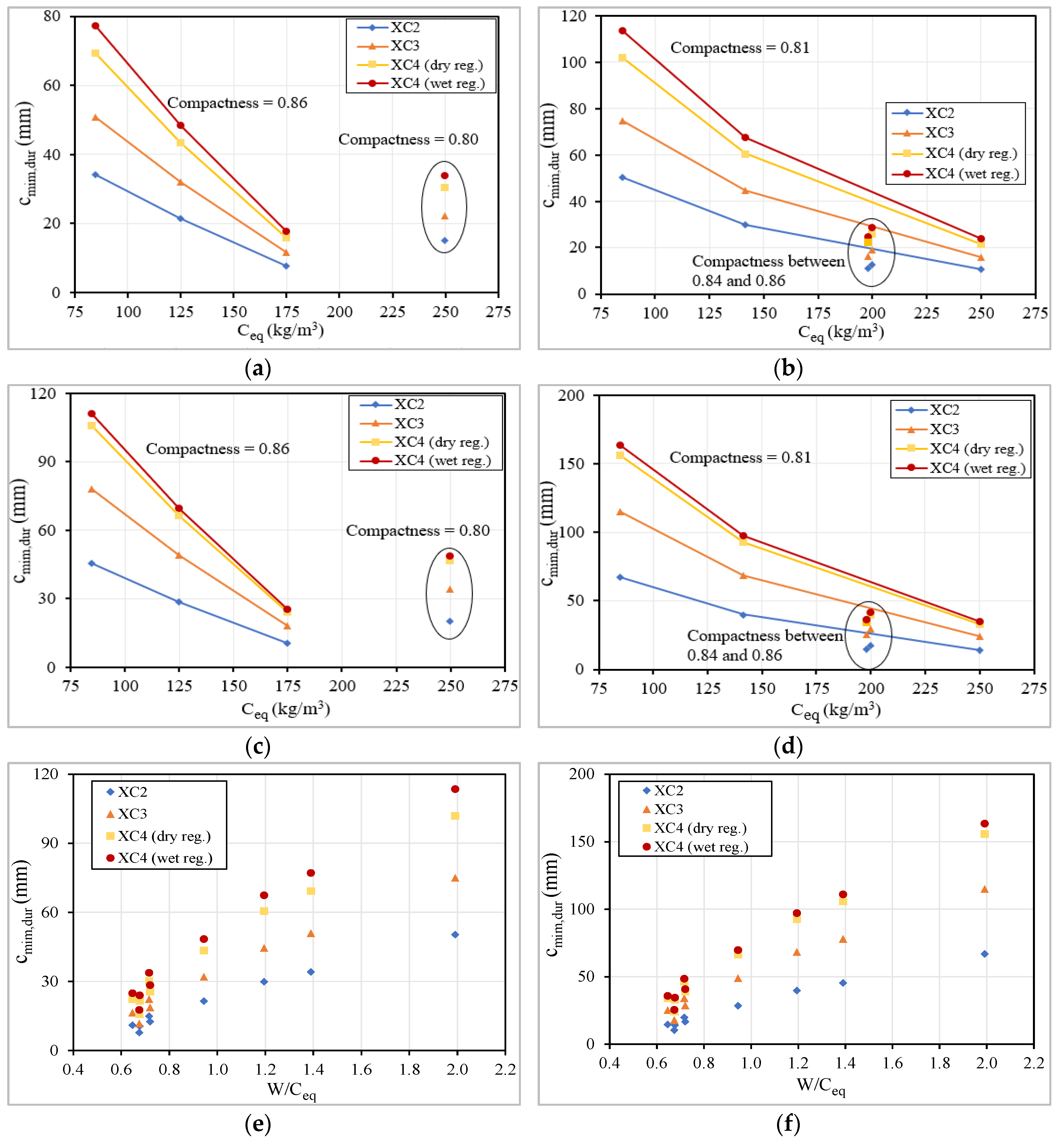

4.6. Lifetime of Structures and Minimum Concrete Cover Regarding Carbonation

5. Conclusions

- Shrinkage: (i) LCC concrete with high compactness of 0.86 and reduced powder dosage (250 kg/m3) promotes reduced shrinkage, tending to increase with the increase of cement dosage; however, in concrete with powder dosage of 350 kg/m3, the increase of compactness tends to gradually decrease shrinkage; (ii) due to the inadequacy of the EC2 prediction of shrinkage, compared to experimental values, a correction is proposed to improve the curves development, where a βshape coefficient assumes different values (0.06 for concrete with powder of 350 kg/m3 and 0.08 for concrete with powder of 250 kg/m3); (iii) beyond the parameters considered by the concrete codes, the concrete compactness has a noticeable influence on the amplitude of concrete shrinkage, mainly when combined with reduced binder powder (250 kg/m3) and very reduced cement dosage, where the experimental/prediction ratio of shrinkage can go down to 0.4.

- Creep: (i) the granulometric reference curve (Faury vs. Alfred), in concrete with reduced binder powder (250 kg/m3), does not have a relevant influence on the evolution and amplitude of creep coefficient; (ii) similarly to the known behavior of current concrete, the creep coefficient is highly influenced by the concrete strength; thus, LCC presents reduction of creep coefficient for concrete with high compactness (0.86) and higher cement dosage (175 kg/m3), which has also higher strength; (iii) a divergence between the shape of the creep curve experimentally obtained and that according to EC2 is noticeable; however, the shape of the creep curve can be improved significantly by adjusting the αt coefficient on βc (t,t0) parameter, from 0.30 to 0.15, for LCC; (iv) there is a huge difference between experimental and EC2 predicted values for the creep of LCC, mainly in concretes with lower cement dosage and with lower compactness (0.80 to 0.81), thus with higher W/B ratio, the creep being ratio experimental/code around 0.3; (v) W/Ceq ratio has a significant influence on that difference, therefore, a corrective parameter is proposed to be included on the β (fcm) coefficient of EC2 to significantly improve the code prediction, namely , which was obtained by correlation analysis.

- Water absorption by immersion: (i) the increase of compactness has a great influence on the reduction of water absorption, since the values for concretes with lower compactness (0.80 to 0.81) are close to 15% and those values reduce to below 10% for concretes with compactness of 0.86; (ii) the W/Ceq ratio also has an influence on absorption, although it is less significant; thus, the relation that incorporates compactness and that ratio, (W/Ceq)0.2/Compactness6, proved by correlation analysis, has high influence on water absorption.

- Water absorption by capillarity: (i) high compactness of LCC combined with higher cement dosage significantly reduces the capillary absorption; (ii) fly ash addition as partial replacement of cement also promotes a significant decrease in capillary absorption; however, its excessive dosage may jeopardize the concrete performance regarding capillarity; (iii) the capillary coefficients of the LCC characterized allow all concretes to be classified as high quality, except the one with reduced compactness (0.81) and very reduced cement dosage (75 kg/m3).

- Carbonation resistance: (i) maintaining the cement dosage, compactness increase has a significant influence on reducing carbonation depth, since the LC series (concrete with high compactness of 0.86 and with 250 kg/m3 of binder powder) exhibits much lower carbonation depth than the corresponding C series (concrete with lower compactness and 350 kg/m3 of binder powder); (ii) maintaining the binder dosage, the carbonation depth decreases with the increase of cement or equivalent cement dosages, since it reduces the W/Ceq ratio; (iii) the higher the amount of fly ash incorporated in the concrete, replacing cement dosage, the lower the carbonation resistance, because it increases the carbonation velocity; (iv) it is possible to produce concrete with good structural performance, with low binder powder of 250 kg/m3 and only 175 kg/m3 of cement dosage, developing higher carbonation resistance, in circa 10%, than current formulation concrete with 250 kg/m3 of cement dosage and binder powder of 350 kg/m3.

- Minimum cover required to avoid corrosion induced by carbonation: (i) it is necessary to use a minimum cement dosage, since only concretes with cement dosage equal or higher than 175 kg/m3 (even though with very different formulation parameters) have adequate resistance to carbonation for general exposure; for those concretes the minimum required covers are lower than those presented in EC2, reaching differences of up to 17 mm; (ii) the compactness increase has also high influence on reducing the minimum cover, since it increases the concrete strength and carbonation resistance; reducing the concrete compactness implies increasing the cover, even if higher cement dosage is used; the LCC with 175 kg/m3 of cement and compactness of 0.86 presents much higher resistance to carbonation compared to that of all formulated concrete, including those with equivalent cement dosage between 200 and 250 kg/m3.

- Lifetime of structures due to carbonation exposure: (i) higher cement dosages promotes longer lifetime; concretes with at least 175 kg/m3 of cement dosage have, submitted to XC2 and XC3 conditions, service lifetime values above the minimum, for current (50 years) and special (100 years) structures and, for XC2, the values are quite high; (ii) for special structures and under XC4 in wet conditions, only the LC175 and C250 have adequate performance, the first due to the high compactness and the latter due to higher cement dosage, being the only mixtures with an expected lifetime of more than 100 years.

- LCC mixtures with a good performance and a long lifetime: (i) concrete with at least 175 kg/m3 of cement dosage reveals adequate combined mechanical, time-dependent and durability performances; (ii) concrete LC175 (with high compactness of 0.86 and powder dosage of only 250 kg/m3) is revealed to be the most eco-efficient of the concretes studied herein, since for current and special structures, and for any type of XC exposure, it is possible to reduce the cover below the standard minimum, presenting a long lifetime; (iii) the amount of cement can be reduced between 37.5% and 42%, depending on the environmental exposure classes XC, comparing the LCC concrete which contains only 175 kg/m3 of cement with the minimum recommendation of 280 kg/m3, for XC2 and XC3, and 300 kg/m3 for XC4.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ecra (European Cement Research Academy). Calcined Clay: A Supplementary Cementitious Material with a Future. Available online: https://ecra-online.org/fileadmin/ecra/newsletter/ECRA_Newsletter_3_2019.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Colaço, R. Reduce the Environmental Impact of Cement (In Portuguese). Constr. Mag. 2019, 90, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- CEMBUREAU. Cementing the European Green Deal—Reaching Climate Neutrality along the Cement and Concrete Value Chain by 2050. Available online: https://cembureau.eu/media/1948/cembureau-2050-roadmap_final-version_web.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Coutinho, J.S. Improving the Durability of Concrete by Treating Formwork, 1st ed.; FEUP: Porto, Portugal, 2005. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Bažant, Z.P. Prediction of Concrete Creep and Shrinkage: Past, Present and Future. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 203, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, H. Structural Concretes of Light Aggregates. Applications in Prefabrication and Reinforcement of Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2012. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M. Creep and Shrinkage of High Performance Lightweight Concrete: A Multi-Scale Investigation. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Klausen, A.E.; Kanstad, T.; Bjøntegaard, Ø.; Sellevold, E. Comparison of Tensile and Compressive Creep of Fly Ash Concretes in the Hardening Phase. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 95, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.H. Effect of Paste Volume on Fresh and Hardened Properties of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mat. 2019, 218, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Coutinho, A. Concrete Manufacturing and Properties; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2006; Volumes 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.; Kahn, L.F.; Kurtis, K.E. Effect of Internally Stored Water on Creep of High-Performance Concrete. ACI Mat. J. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1992-1-1. Eurocode 2—Design of Concrete Structures Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- CEB-FIP Model Code. First Complete Draft-Vol.1. In fib–International Federation for Structural Concrete; EPFL: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Bisschop, J. On the Origin of Eigenstresses in Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Jensen, O.M.; Van Breugel, K. Autogenous Shrinkage in High-Performance Cement Paste: An Evaluation of Basic Mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueramae, S.; Tangchirapat, W.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Sukontasukkul, P. Autogenous and Drying Shrinkages of Mortars and Pore Structure of Pastes Made with Activated Binder of Calcium Carbide Residue and Fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.; Júlio, E.; Lourenço, J. New Approach for Shrinkage Prediction of High-Strength Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 35, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M.; Brooks, J. Concrete Technology, 2nd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P. High-Performance, High-Volume Fly Ash Concrete for Sustainable Development. In International Workshop on Sustainable Development and Concrete Technology; Iowa State University: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, J.S. Eco-Efficient Concrete with Waste. In JMC’2011-1st Journeys on Building Materials; FEUP: Porto, Portugal, 2011; pp. 171–214. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P. Sustainable Cements and Concrete for the Climate Change Era—A Review. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Sustainable Constrution Materials and Tecnologies, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy, 28–30 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.; Monteiro, P. Concrete in the Era of Global Warming and Sustainability. In Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bentz, D.P.; Hansen, A.S.; Guynn, J.M. Optimization of Cement and Fly Ash Particle Sizes to Produce Sustainable Concretes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogas, J.A.; Real, S. A Review on the Carbonation and Chloride Penetration Resistance of Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.J.; Ng, P.L.; Chu, S.H.; Guan, G.X.; Kwan, A.K.H. Ternary Blending with Metakaolin and Silica Fume to Improve Packing Density and Performance of Binder Paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 252, 119031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, N.; Kumar, R.; Zahid, M.; Tufail, R.F. Effects of Modified Metakaolin Using Nano-Silica on the Mechanical Properties and Durability of Concrete. Materials 2019, 12, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Özdiş, B.E.; Çam, N.F.; Canbaz Öztürk, B. Assessment of Natural Radioactivity in Cements Used as Building Materials in Turkey. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017, 311, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Monteiro, P. Concrete: Microstructure Properties and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Proske, T.; Hainer, S.; Rezvani, M.; Graubner, C. Eco-Friendly Concretes with Reduced Water and Cement Content – Mix Design Principles and Application in Practice. Constr. Build. Mater. J. 2014, 67, 307–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.; Branco, F.; Camões, A. Eco-Efficient Concrete Study through the Use of Biomass Fly Ash. In Proceedings of the 3rd Luso-Brazilian Congress on Sustainable Construction Materials, Coimbra, Portugal, 14–16 February 2018. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Nasvik, J. Sustainable Concrete Structures—How to Use Concrete for Sustainable Purposes. Concr. Constr. 2013, 2, 765–778. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, H.; Alves, H.; Freitas, E.; Júlio, E. Mechanical Performance of Concrete with Low Cement Dosage. In Proceedings of the National Meeting of Structural Concrete–BE2016, Coimbra, Portugal, 2–4 November 2016. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Fennis, S.; Walraven, J.; Uijl, J. Compaction-Interaction Packing Model: Regarding the Effect of Fillers in Concrete Mixture Design. Mat. Struct. 2013, 46, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, A.; Giergiczny, Z.; Kuterasińska-Warwas, J. Properties of Concrete Made with Low-Emission Cements CEM II/C-M and CEM VI. Materials 2020, 13, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, K.; Haha, M.; Le Saout, G.; Kjellsen, K.; Justnes, H.; Lothenbach, B. Hydration Mechanisms of Ternary Portland Cements Containing Limestone Powder and Fly Ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P.; Sato, T.; de la Varga, I.; Weiss, W.J. Fine Limestone Additions to Regulate Setting in High Volume Fly Ash Mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakali, G.; Tsivilis, S.; Aggeli, E.; Bati, M. Hydration Products of C3A, C3S and Portland Cement in the Presence of CaCO3. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, G.; Bonavetti, V.; Irassar, E. Strength Development of Ternary Blended Cement with Limestone Filler and Blast-Furnace Slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 206-1. Concrete–Part 1: Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Björnström, J.; Chandra, S. Effect of Superplasticizers on the Rheological Properties of Cements. Mat. Struct. 2003, 36, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A. Effect of Class F Fly Ash on the Durability Properties of Concrete. Sust. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.M.; Huang, R.; Yang, C.C. Effects of Carbonation on Mechanical Properties and Durability of Concrete Using Accelerated Testing Method. J. Mar. Sci.Technol. 2002, 10, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Binici, H.; Shah, T.; Aksogan, O.; Kaplan, H. Durability of Concrete Made with Granite and Marble as Recycle Aggregates. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 208, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Bhunia, D.; Singh, S. Comparative Study of Accelerated Carbonation of Plain Cement and Fly-Ash Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 10, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proske, T.; Hainer, S.; Rezvani, M.; Graubner, C. Eco-Friendly Concretes with Reduced Water and Cement Content: Mix Design Principles and Experimental Tests. Constr. Build. Mater. J. 2016, 67, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, G. Evaluation of Water Absorption of Concrete as a Measure for Resistance against Carbonation and Chloride Migration. Mater. Struct. 2004, 37, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faury, J. Le Bêton, 3rd ed.; Dunod: Paris, France, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, E.; Costa, H.; Louro, A.S.; Pipa, M.; Júlio, E. Adherence between Steel Bars and Concrete with Low Binder Dosage. In Proceedings of the National Meeting of Structural Concrete–BE2016, Coimbra, Portugal, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, J.; Júlio, E.; Maranha, P. Expanded Clay Lightweight Aggregate Concrete; APEB: Lisbon, Portugal, 2004. (in Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Fennis, S.; Walraven, J. Using Particle Packing Technology for Sustainable Concrete Mixture Design. Heron 2012, 57, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, J.; Dinger, D. Derivation of the Dinger-Funk Particle Size Distribution Equation. In Predictive Process Control of Crowded Particulate Suspensions: Applied to Ceramic Manufacturing; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12350-2. Testing Fresh Concrete–Part 2: Slump-Test; British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12350-4. Testing Fresh Concrete Part 4: Degree of Compactability; British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12390-3. Testing Hardened Concrete Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens; British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12390-6. Testing Hardened Concrete–Part 6: Tensile Splitting Strength of Test Specimens; British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EN 12390-5. Testing Hardened Concrete Part 5: Flexural Strength of Test Specimens; British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- E 397. Hardened Concrete–Determination of the Modulos of Elasticity of Concrete in Compression; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- E 399. Concrete. Chraracterization of Creep in Compressive Test; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- E 398. Hardened Concrete. Determination of the Shrinkage and of the Swelling; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- E 393. Concrete. Determination of the Absorption of Water through Capillarity; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- E 394. Concrete. Determination of the Absorption of Water by Immersion; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- E391. Concrete. Determination of Carbonation Resistance; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.G.; Feng, J.J.; Zhu, J.; Chu, S.H.; Kwan, A.K.H. Pervious Concrete: Effects of Porosity on Permeability and Strength. Mag. Concr. Res. 2019, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y. Relationship between Water Permeability and Pore Structure of Cementitious Materials. Mag. Concr. Res. 2019, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Feng, N.; Yang, J.; Zheng, X. Effect of Superfine Slag Powder on Cement Properties. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Chu, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, H.S. Coupling Effect of γ-Dicalcium Silicate and Slag on Carbonation Resistance of Low Carbon Materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camões, A. Eco-Efficient Concrete with Low Cement Content. In Metacaulino in Portugal: Production, Application and Sustainability; C-TAC, University of Minho: Aveiro, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Woyciechowski, P.; Woliński, P.; Adamczewski, G. Prediction of Carbonation Progress in Concrete Containing Calcareous Fly Ash Co-Binder. Materials 2019, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- E465. Concrete. Methodology for Estimating the Concrete Performance Properties Allowing to Comply with the Design Working Life ofthe Reinforced or Prestressed Concrete Structures under the Environmental Exposures XC and XS; National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LNEC): Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, E.; Louro, A.S.; Costa, H.; Cavaco, E.S.; Júlio, E.; Pipa, M. Bond Behaviour between Steel/Stainless-Steel Reinforcing Bars and Low Binder Concrete (LBC). Eng. Struct. 2020, 221, 111072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.H.; Jiang, Y.; Kwan, A.K.H. Effect of rigid fibres on aggregate packing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.H.; Li, L.G.; Kwan, A.K.H. Fibre factors governing the fresh and hardened properties of steel FRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constituents | LC75 | LC75F | C75 | LC125 | LC125F | C125 | LC175 | LC175F | C175B | C200B | LC250A | C250 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (kg/m3) | 75 | 75 | 75 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 175 | 175 | 175 | 200 | 250 | 250 |

| Lf (kg/m3) | 75 | 75 | 75 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 75 | 75 | 100 | 150 | - | 100 |

| FA (kg/m3) | 100 | 100 | 200 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 75 | - | - | - |

| SKY (kg/m3) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| W (kg/m3) | 118 | 118 | 169 | 118 | 118 | 169 | 118 | 118 | 128 | 144 | 179 | 169 |

| S0/3 (kg/m3) | 44 | 587 | 286 | 44 | 671 | 371 | 44 | 747 | 181 | 186 | 218 | 492 |

| S0/4 (kg/m3) | 1068 | 308 | 585 | 1080 | 244 | 520 | 1084 | 210 | 762 | 742 | 817 | 427 |

| G4/8 (kg/m3) | 284 | 78 | 106 | 287 | 82 | 110 | 288 | 98 | 92 | 96 | 278 | 116 |

| C6/14 (kg/m3) | 623 | 1050 | 798 | 631 | 1049 | 797 | 633 | 997 | 894 | 869 | 587 | 795 |

| Total aggregates (kg/m3) | 2018 | 2023 | 1774 | 2042 | 2047 | 1798 | 2048 | 2053 | 1929 | 1893 | 1900 | 1831 |

| W/C | 1.57 | 1.57 | 2.26 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Equiv.-cement, Ceq (kg/m3) | 85 | 85 | 85 | 125 | 125 | 142 | 175 | 175 | 198 | 200 | 250 | 250 |

| W/Ceq | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.99 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 1.19 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| W/B | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.72 | 0.48 |

| Compactness | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| LCC Mixtures | fcm,7 (MPa) | fcm,28 (MPa) | fcm,56 (MPa) | Ecm (GPa) | fctm,f (MPa) | fctm,sp (MPa) | Slump (mm) | D_Comp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC75 | 11.6 | 20.6 | 26.5 | 37.4 | 3.2 | 1.5 | - | 1.21 |

| LC75F | 15.7 | 22.1 | - | 28.7 | - | - | 50 | - |

| C75 | 7.6 | 15.2 | 20.5 | - | 2.1 | 0.7 | 90 | - |

| LC125 | 25.2 | 28.9 | 33.9 | 40.6 | 4.5 | 2.3 | - | 1.23 |

| LC125F | 26.4 | 29.4 | - | 34.5 | - | - | 45 | - |

| C125 | 14.3 | 20.3 | 26.5 | - | 3.6 | 1.5 | 120 | - |

| LC175 | 35.0 | 44.7 | 50.2 | 42.4 | 6.9 | 3.4 | - | 1.25 |

| LC175F | 36.8 | 45.9 | - | 38.2 | - | - | 65 | - |

| C175B | 36.2 | 50.1 | 52.9 | 47.9 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 107 | - |

| C200B | 32.9 | 38.2 | 39.1 | 41.3 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 110 | - |

| LC250A | 25.8 | 30.5 | 34.3 | 38.1 | 5.1 | 2.2 | - | 1.16 |

| C250 | 34.9 | 39.1 | 41.5 | 36.5 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 80 | - |

| Cd (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCC Mixtures | Days | ||||

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 42 | |

| LC75 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 23.3 | 36.5 | 43.3 |

| C75 | 17.5 | 22.5 | 39.0 | 49.9 | - |

| LC125 | 5.5 | 11.0 | 15.3 | 21.8 | 26.4 |

| C125 | 10.0 | 15.5 | 20.0 | 27.8 | 33.5 |

| LC175 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 10.0 |

| C175B | - | 4.8 | - | 10.3 | 12.9 |

| C200B | - | 5.3 | - | 12.3 | 14.7 |

| LC250A | 4.5 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 15.8 | 18.1 |

| C250 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 11.0 |

| RC65 (kg·year/m5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCC Mixtures | - | - | Days | - | - | Average |

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 42 | ||

| LC75 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 13 |

| C75 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 | - | 5 |

| LC125 | 49 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 33 |

| C125 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 17 |

| LC175 | 370 | 282 | 209 | 170 | 207 | 248 |

| C175B | - | 153 | - | 129 | 125 | 125 |

| LC250A | 73 | 82 | 66 | 56 | 63 | 68 |

| C200B | - | 123 | - | 91 | 15 | 80 |

| C250 | 121 | 138 | 101 | 138 | 171 | 134 |

| Intended Service Lifetime | Propagation Time and Period of Initiation | XC2 (Wet, Rarely Dry) | XC3 (Moderate Humidity) | XC4 (Dry Regime) | XC4 (Wet Regime) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tg = 50 years (RC2) | tp (years) | 10 | 45 | 15 | 5 |

| tic (years) | 92 | 12 | 80 | 105 | |

| tg = 100 years (RC3) | tp (years) | 20 | 90 | 20 | 10 |

| tic (years) | 224 | 28 | 224 | 252 |

| Minimum Cover cmin,dur (mm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Class | Current Structures (Class S4) | Special Structures (Class S5) | ||||||

| Exposure Classes | XC2 | XC3 | XC4 (Dry Reg.) | XC4(Wet Reg.) | XC2 | XC3 | XC4 (Dry Reg.) | XC4 (Wet Reg.) |

| EC2 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 35 | ||

| LC75 | 34 | 51 | 69 | 77 | 45 | 78 | 106 | 111 |

| C75 | 50 | 75 | 102 | 114 | 67 | 115 | 156 | 163 |

| LC125 | 21 | 32 | 43 | 48 | 29 | 49 | 66 | 70 |

| C125 | 30 | 45 | 61 | 67 | 40 | 68 | 93 | 97 |

| LC175 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 10 | 18 | 24 | 25 |

| C175B | 11 | 16 | 22 | 25 | 15 | 25 | 34 | 36 |

| LC250A | 15 | 22 | 30 | 34 | 20 | 34 | 46 | 49 |

| C200B | 13 | 19 | 25 | 28 | 17 | 29 | 39 | 41 |

| C250 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 24 | 14 | 24 | 33 | 35 |

| Structural Class | Current and Special Structures (Classes S4 and S5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Cement | CEM I; CEM II/A (1) | ||||

| Exposure Class | XC2 | XC3 | XC4 (Wet and Dry Reg.) | ||

| EN 206 | Minimum dosage of C (kg/m3) | 280 | 280 | 300 | |

| Maximum W/C ratio | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.50 | ||

| - | - | Total powder (kg/m3) | Equivalent dosage of cement, Ceq (kg/m3) | W/Ceq | |

| - | Concretes | LC75 | 250 | 85 | 1.39 |

| LC125 | 125 | 0.94 | |||

| LC175 | 175 | 0.67 | |||

| LC250A | 250 | 0.47 | |||

| C75 | 350 | 85 | 2.25 | ||

| C125 | 142 | 0.97 | |||

| C175B | 198 | 0.73 | |||

| C200B | 200 | 0.72 | |||

| C250 | 250 | 0.68 | |||

| Structural Class | Current Structures (Class S4, RC2, 50 Years) | Special Structures (Class S5, RC3, 100 Years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Class | XC2 | XC3 | XC4 (Dry Reg.) | XC4 (Wet Reg.) | XC2 | XC3 | XC4 (Dry Reg.) | XC4 (Wet Reg.) | |

| Concretes | cmin,dur (mm) | 25 | 30 | 30 | 35 | ||||

| LC75 | tg (years) | 25 | 46 | 19 | 9 | 42 | 91 | 25 | 15 |

| C75 | 15 | 46 | 17 | 7 | 27 | 91 | 22 | 12 | |

| LC125 | 75 | 48 | 29 | 19 | 114 | 94 | 37 | 27 | |

| C125 | 33 | 47 | 21 | 11 | 53 | 92 | 27 | 17 | |

| LC175 | >>>> 200 | 69 | 179 | 169 | >> 200 | 119 | 216 | 206 | |

| C175B | >> 200 | 57 | 86 | 76 | >> 200 | 104 | 105 | 95 | |

| LC250A | >> 200 | 51 | 49 | 39 | >> 200 | 98 | 60 | 50 | |

| C200B | >> 200 | 54 | 67 | 57 | >> 200 | 101 | 82 | 72 | |

| C250 | >> 200 | 58 | 92 | 82 | >> 200 | 105 | 113 | 103 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robalo, K.; Soldado, E.; Costa, H.; Carvalho, L.; do Carmo, R.; Júlio, E. Durability and Time-Dependent Properties of Low-Cement Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163583

Robalo K, Soldado E, Costa H, Carvalho L, do Carmo R, Júlio E. Durability and Time-Dependent Properties of Low-Cement Concrete. Materials. 2020; 13(16):3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163583

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobalo, Keila, Eliana Soldado, Hugo Costa, Luís Carvalho, Ricardo do Carmo, and Eduardo Júlio. 2020. "Durability and Time-Dependent Properties of Low-Cement Concrete" Materials 13, no. 16: 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163583

APA StyleRobalo, K., Soldado, E., Costa, H., Carvalho, L., do Carmo, R., & Júlio, E. (2020). Durability and Time-Dependent Properties of Low-Cement Concrete. Materials, 13(16), 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163583