Room-Temperature Catalyst Enables Selective Acetone Sensing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pt/Al2O3 Fabrication

2.2. Pt/Al2O3 Characterization

2.3. Catalytic Evaluation

2.4. Detector Fabrication and Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

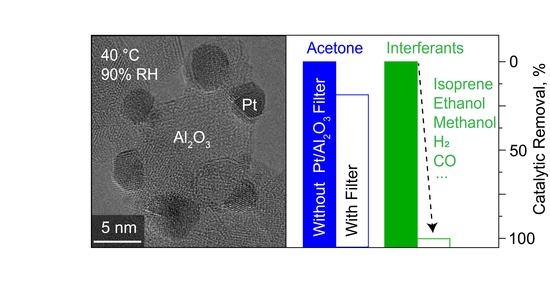

3.1. Tailoring Pt Size and Dispersion

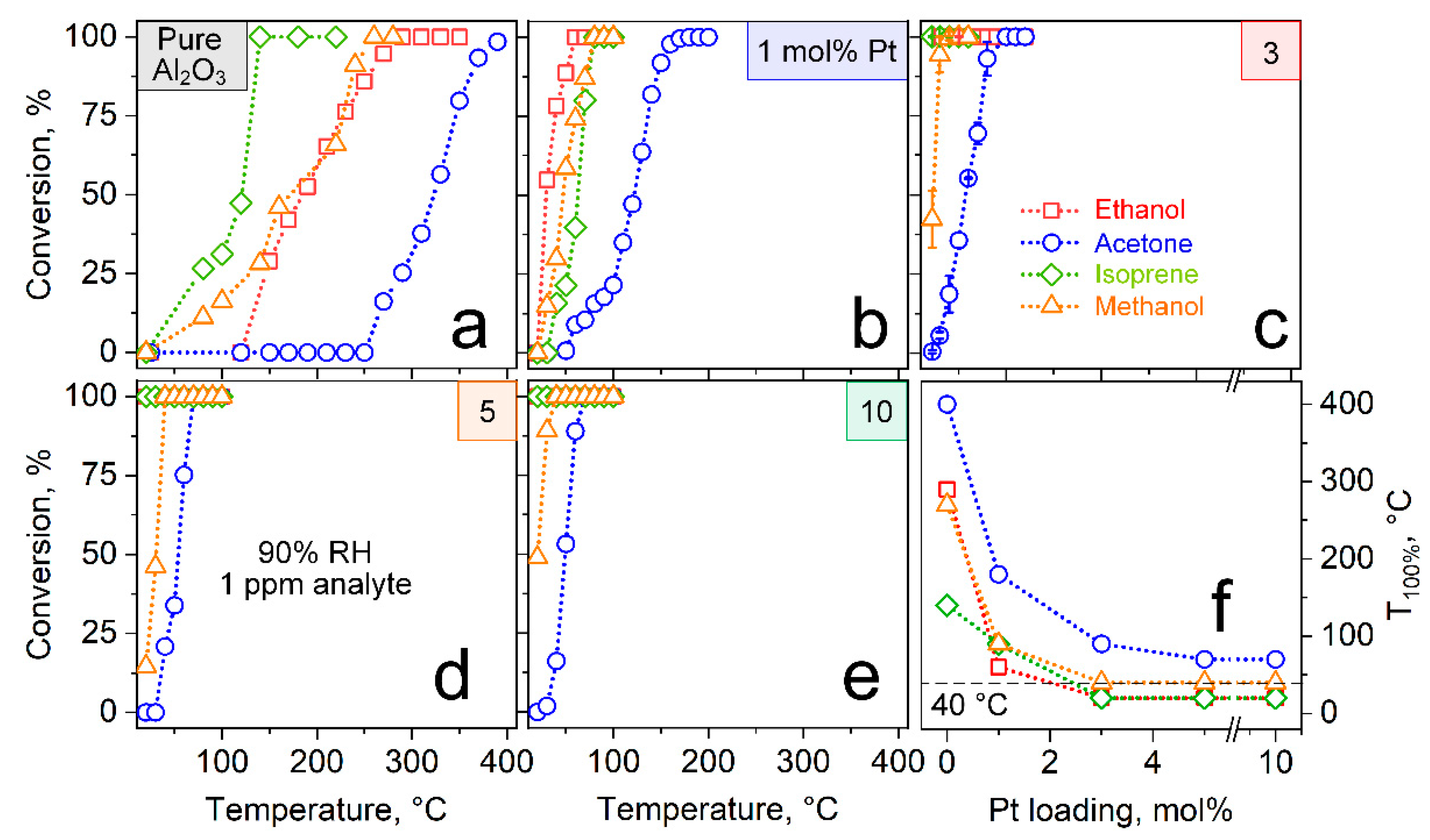

3.2. Catalytic Reactivity

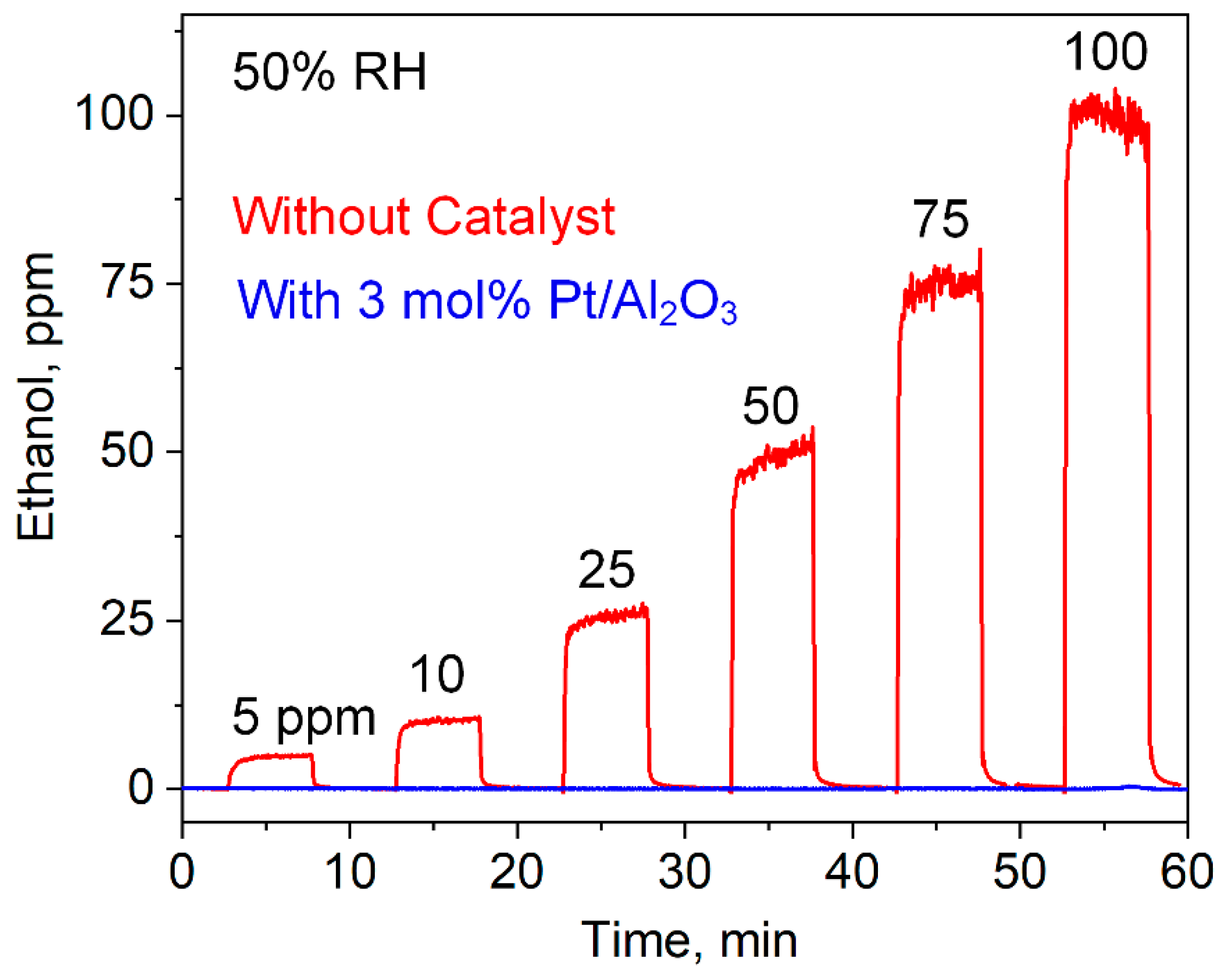

3.3. Selective Acetone Sensing with Room Temperature Filter

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moon, Y.K.; Jeong, S.Y.; Jo, Y.K.Y.M.; Kang, Y.K.; Lee, J.H. Highly Selective Detection of Benzene and Discrimination of Volatile Aromatic Compounds Using Oxide Chemiresistors with Tunable Rh-TiO2 Catalytic Overlayers. Adv. Sci. 2021, 2004078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broek, J.; Abegg, S.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Güntner, A.T. Highly selective detection of methanol over ethanol by a handheld gas sensor. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, J.; Davis, C.E.; Pleil, J.D. Breathborne Biomarkers and the Human Volatilome; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-819967-1. [Google Scholar]

- Güntner, A.T.; Pineau, N.J.; Mochalski, P.; Wiesenhofer, H.; Agapiou, A.; Mayhew, C.A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Sniffing Entrapped Humans with Sensor Arrays. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 4940–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruzsanyi, V.; Wiesenhofer, H.; Ager, C.; Herbig, J.; Aumayr, G.; Fischer, M.; Renzler, M.; Ussmueller, T.; Lindner, K.; Mayhew, C.A. A portable sensor system for the detection of human volatile compounds against transnational crime. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 328, 129036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broek, J.; Weber, I.C.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Highly selective gas sensing enabled by filters. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 661–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lacy Costello, B.; Amann, A.; Al-Kateb, H.; Flynn, C.; Filipiak, W.; Khalid, T.; Osborne, D.; Ratcliffe, N.M. A review of the volatiles from the healthy human body. J. Breath Res. 2014, 8, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, O.O.; Alm, S.; Katsouyanni, K.; Künzli, N.; Maroni, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Saarela, K.; Srám, R.J.; Zmirou, D.; Jantunen, M.J. The EXPOLIS study: Implications for exposure research and environmental policy in Europe. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 2004, 14, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoff, M.A.; Grace, R.; Guzman, A.M.; Runco, P.D.; Yannopoulos, L.N. Enhancement of MOS gas sensor selectivity by “on-chip” catalytic filtering. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1991, 5, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, M.; Kornely, S.; Weh, T.; Frank, J.; Meixner, H. Selective gas detection with high-temperature operated metal oxides using catalytic filters. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2000, 69, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statheropoulos, M.; Agapiou, A.; Georgiadou, A. Analysis of expired air of fasting male monks at Mount Athos. J. Chromatogr. B 2006, 832, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntner, A.T.; Kompalla, J.F.; Landis, H.; Theodore, S.J.; Geidl, B.; Sievi, N.A.; Kohler, M.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Gerber, P.A. Guiding ketogenic diet with breath acetone sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Güntner, A.T.; Sievi, N.A.; Theodore, S.J.; Gulich, T.; Kohler, M.; Pratsinis, S.E. Noninvasive Body Fat Burn Monitoring from Exhaled Acetone with Si-doped WO3-sensing Nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 10578–10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzsányi, V.; Kalapos, M.P. Breath acetone as a potential marker in clinical practice. J. Breath Res. 2017, 11, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Li, S.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Han, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, P. Improved selective acetone sensing properties of Co-doped ZnO nanofibers by electrospinning. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 155, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifani, M.; Comini, E.; Díaz, R.; Genç, A.; Andreu, T.; Siciliano, P.; Morante, J.R. Acetone sensors based on TiO2 nanocrystals modified with tungsten oxide species. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 665, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Kupferthaler, A.; Unterkofler, K.; Koc, H.; Teschl, S.; Teschl, G.; Miekisch, W.; Schubert, J.; Hinterhuber, H.; Amann, A. Isoprene and acetone concentration profiles during exercise on an ergometer. J. Breath Res. 2009, 3, 027006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, R.; Güntner, A.T.; Park, Y.; Rim, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, W. Sensing of acetone by Al-doped ZnO. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 283, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.C.; Braun, H.P.; Krumeich, F.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Superior Acetone Selectivity in Gas Mixtures by Catalyst-Filtered Chemoresistive Sensors. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narjinary, M.; Rana, P.; Sen, A.; Pal, M. Enhanced and selective acetone sensing properties of SnO2-MWCNT nanocomposites: Promising materials for diabetes sensor. Mater. Des. 2017, 115, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, T.H.; Sohn, W.; Suh, J.M.; Shim, Y.S.; Kwon, K.C.; Hong, K.; Choi, S.; Byun, H.G.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Au decoration of vertical hematite nanotube arrays for further selective detection of acetone in exhaled breath. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 274, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessonneau, V.; Thomas, O. Assessment of exposure to alcohol vapor from alcohol-based hand rubs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Güntner, A.T.; Weber, I.C.; Pratsinis, S.E. Catalytic filter for continuous and selective ethanol removal prior to gas sensing. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, N.C.; Lee, J.S.; Tae, E.L.; Lee, Y.J.; Yoon, K.B. Acidity scale for metal oxides and Sanderson’s electronegativities of lanthanide elements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 10128–10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.M.; Lim, K.; Choi, H.J.; Yoon, J.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H. 2D metal-organic framework derived co-loading of Co3O4 and PdO nanocatalysts on In2O3 hollow spheres for tailored design of high-performance breath acetone sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 325, 128821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.C.; Derron, N.; Königstein, K.; Gerber, P.A.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Monitoring Lipolyis by Sensing Breath Acetone down to ppb. Small Sci. 2021, 2100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, T.; Baiker, A. Oxidation of Alcohols with Molecular Oxygen on Solid Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3037–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.L.; Yan, B.; Liang, Y.; Xu, B.Q. Water effects on the acidic property of typical solid acid catalysts by 3,3-dimethybut-1-ene isomerization and 2-propanol dehydration reactions. Catal. Today 2017, 295, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.G.; Fripiat, J.J. Acetone condensation reaction on acid catalysts. J. Catal. 1998, 178, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvedar, J.C.; Fogel, A.L. MHealth advances clinical research, bit by bit. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroi, T. Role of Precious Metal Catalysts. In Noble Metals; Industrial Catalysts Laboratory: Kukushima, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Sapi, A.; An, K.; Kennedy, G.; Michalak, W.D.; Somorjai, G.A. Influence of Size-Induced Oxidation State of Platinum Nanoparticles on Selectivity and Activity in Catalytic Methanol Oxidation in the Gas Phase. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2976–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotta, L.F. Catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds on supported noble metals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 100, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneda, M.; Wantanabe, T.; Kamiuchi, N.; Ozawa, M. Effect of platinum dispersion on the catalytic activity of Pt/Al2O3 for the oxidation of carbon monoxide and propene. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 142–143, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Španěl, P.; Smith, D. A longitudinal study of methanol in the exhaled breath of 30 healthy volunteers using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry, SIFT-MS. Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourtelesis, M.; Panagiotopoulou, P.; Verykios, X.E. Influence of structural parameters on the reaction of low temperature ethanol steam reforming over Pt/Al2O3 catalysts. Catal. Today 2015, 258, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garetto, T.F.; Apesteguía, C.R. Oxidative catalytic removal of hydrocarbons over Pt/Al2O3 catalysts. Catal. Today 2000, 62, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, R.; Stark, W.J.; Mädler, L.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Baiker, A. Flame-made platinum/alumina: Structural properties and catalytic behaviour in enantioselective hydrogenation. J. Catal. 2003, 213, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righettoni, M.; Tricoli, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Thermally stable, silica-doped ε-WO3 for sensing of acetone in the human breath. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 3152–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mädler, L.; Kammler, H.K.; Mueller, R.; Pratsinis, S.E. Controlled synthesis of nanostructured particles by flame spray pyrolysis. J. Aerosol Sci. 2002, 33, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntner, A.T.; Pineau, N.J.; Chie, D.; Krumeich, F.; Pratsinis, S.E. Selective sensing of isoprene by Ti-doped ZnO for breath diagnostics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 5358–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güntner, A.T.; Righettoni, M.; Pratsinis, S.E. Selective sensing of NH3 by Si-doped α-MoO3 for breath analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 223, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntner, A.T.; Wied, M.; Pineau, N.J.; Pratsinis, S.E. Rapid and Selective NH3 Sensing by Porous CuBr. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 19033907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ellis, A.M.; Mayhew, C.A. Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781405176682. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.; Mikoviny, T.; Feil, S.; Haidacher, S.; Hanel, G.; Hartungen, E.; Jordan, A.; Märk, L.; Mutschlechner, P.; Schottkowsky, R.; et al. A compact PTR-ToF-MS instrument for airborne measurements of volatile organic compounds at high spatiotemporal resolution. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, K.; Filipiak, W.; Amann, A. Determining concentration patterns of volatile compounds in exhaled breath by PTR-MS. J. Breath Res. 2009, 3, 027002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntner, A.T.; Koren, V.; Chikkadi, K.; Righettoni, M.; Pratsinis, S.E. E-nose Sensing of Low-ppb Formaldehyde in Gas Mixtures at High Relative Humidity for Breath Screening of Lung Cancer? ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righettoni, M.; Tricoli, A.; Gass, S.; Schmid, A.; Amann, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Breath acetone monitoring by portable Si:WO3 gas sensors. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 738, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tricoli, A.; Graf, M.; Mayer, F.; Kühne, S.; Hierlemann, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Micropatterning layers by flame aerosol deposition-annealing. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3005–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, S.; Theodore, S.J.; Güntner, A.T. Versatile breath sampler for online gas sensor analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 273, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessman, J.; Stefan, R.I.; Van Staden, J.F.; Danzer, K.; Lindner, W.; Burns, D.T.; Fajgelj, A.; Müller, H. Selectivity in analytical chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jang, E.J.; Kwak, J.H. Effect of number and properties of specific sites on alumina surfaces for Pt-Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 569, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Hattori, T. The support effect on platinum catalyst under oxidizing atmosphere: Improvement in the oxidation-resistance of platinum by the electrophilic property of support materials. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2002, 237, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casapu, M.; Fischer, A.; Gänzler, A.M.; Popescu, R.; Crone, M.; Gerthsen, D.; Türk, M.; Grunwaldt, J.D. Origin of the Normal and Inverse Hysteresis Behavior during CO Oxidation over Pt/Al2O3. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touir, H.; Dixmier, J.; Zellama, K.; Morhange, J.F.; Elkaim, P. Bimodal crystal size distribution in annealed r.f. magnetron silicon films: A memory effect of the local order inhomogeneities in the initial amorphous state. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 1998, 227–230, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, D.; Kwak, J.H.; Hu, J.; Cho, S.J.; Szanyi, J.; Allard, L.F.; Peden, C.H.F. Unique Role of Anchoring Penta-Coordinated Al3+ Sites in the Sintering of γ-Al2O3-Supported Pt Catalysts. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 2688–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibi, P.T.Z.; Zhdanov, V.P.; Langhammer, C.; Grönbeck, H. Transient Bimodal Particle Size Distributions during Pt Sintering on Alumina and Silica. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. 1976, A32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Španěl, P.; Smith, D. A longitudinal study of ammonia, acetone and propanol in the exhaled breath of 30 subjects using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry, SIFT-MS. Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrus, L.; Guenard, H.; Vardon, G.; Varene, P. Respiratory Water Loss. Respir. Physiol. 1980, 39, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, D.R.; Grass, M.E.; Zeng, Z.; Aksoy, F.; Bluhm, H.; Li, W.X.; Mun, B.S.; Somorjai, G.A.; Liu, Z. In situ oxidation study of Pt(110) and its interaction with CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20319–20325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliaee, S.N.; Khodadadi, A.; Mortazavi, Y.; Alipour, S. Highly selective Pt/SnO2 sensor to propane or methane in presence of CO and ethanol, using gold nanoparticles on Fe2O3 catalytic filter. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 147, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righettoni, M.; Tricoli, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Si:WO3 sensors for highly selective detection of acetone for easy diagnosis of diabetes by breath analysis. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3581–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königstein, K.; Abegg, S.; Schorn, A.N.; Weber, I.C.; Derron, N.; Krebs, A.; Gerber, P.A.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Güntner, A.T. Breath acetone change during aerobic exercise is moderated by cardiorespiratory fitness. J. Breath Res. 2020, 15, 016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eranna, G.; Joshi, B.C.; Runthala, D.P.; Gupta, R.P. Oxide Materials for Development of Integrated Gas Sensors—A Comprehensive Review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 29, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegg, S.; Magro, L.; Van den Broek, J.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Güntner, A.T. A pocket-sized device enables detection of methanol adulteration in alcoholic beverages. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntner, A.T.; Abegg, S.; Königstein, K.; Gerber, P.A.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Breath Sensors for Health Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weber, I.C.; Wang, C.-t.; Güntner, A.T. Room-Temperature Catalyst Enables Selective Acetone Sensing. Materials 2021, 14, 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14081839

Weber IC, Wang C-t, Güntner AT. Room-Temperature Catalyst Enables Selective Acetone Sensing. Materials. 2021; 14(8):1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14081839

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeber, Ines C., Chang-ting Wang, and Andreas T. Güntner. 2021. "Room-Temperature Catalyst Enables Selective Acetone Sensing" Materials 14, no. 8: 1839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14081839