Aplitic Granite Waste as Raw Material for the Production of Outdoor Ceramic Floor Tiles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

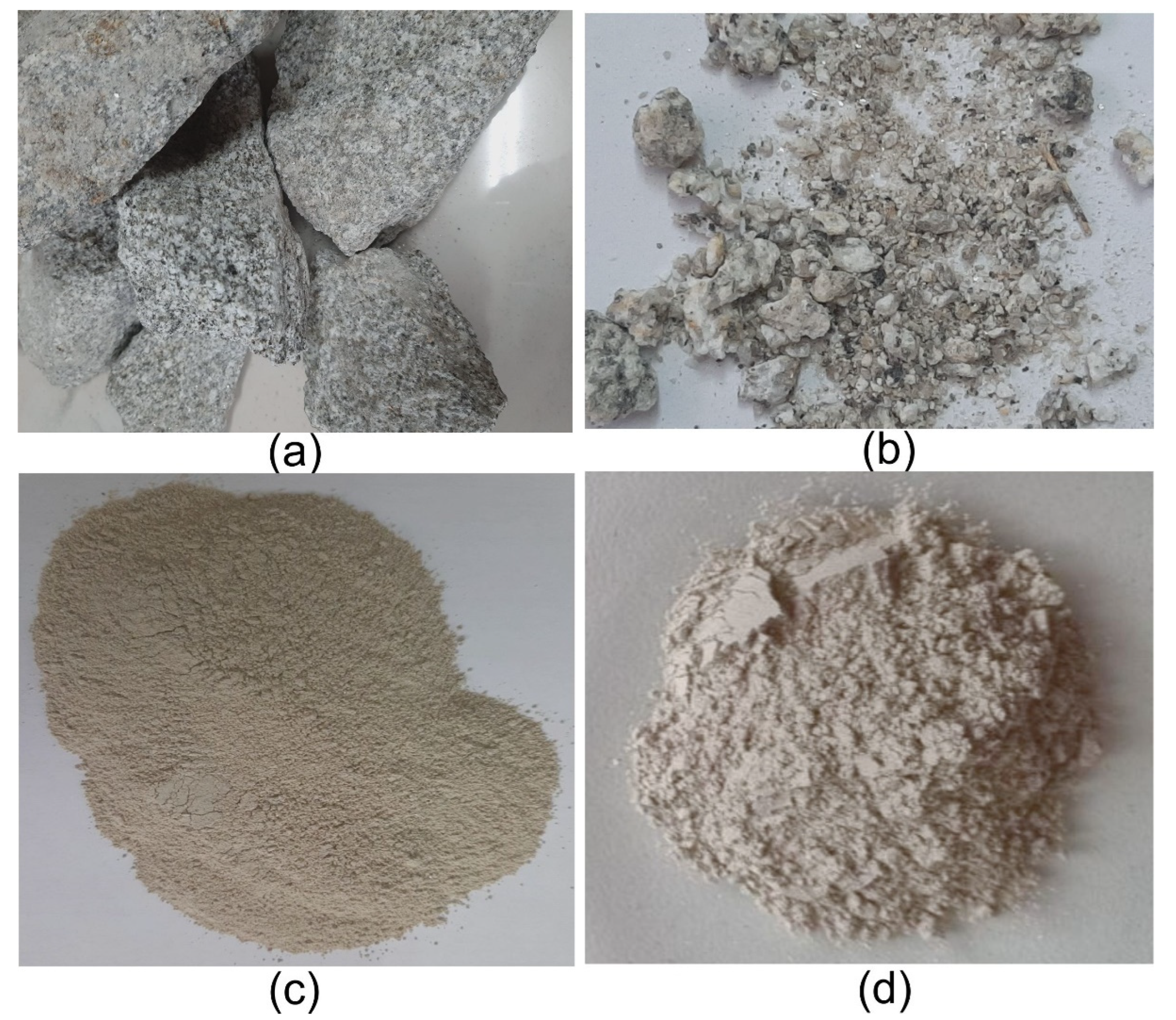

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

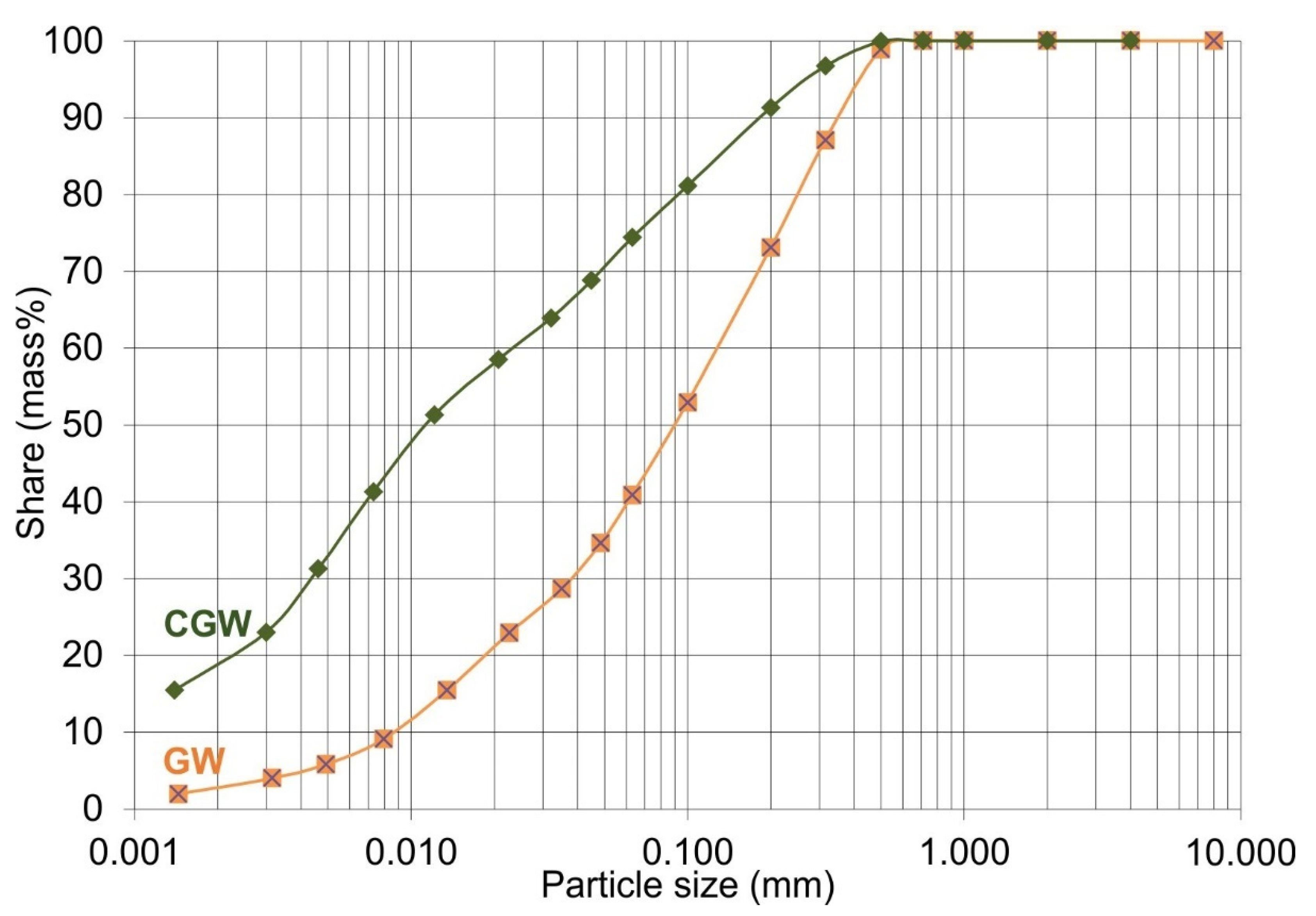

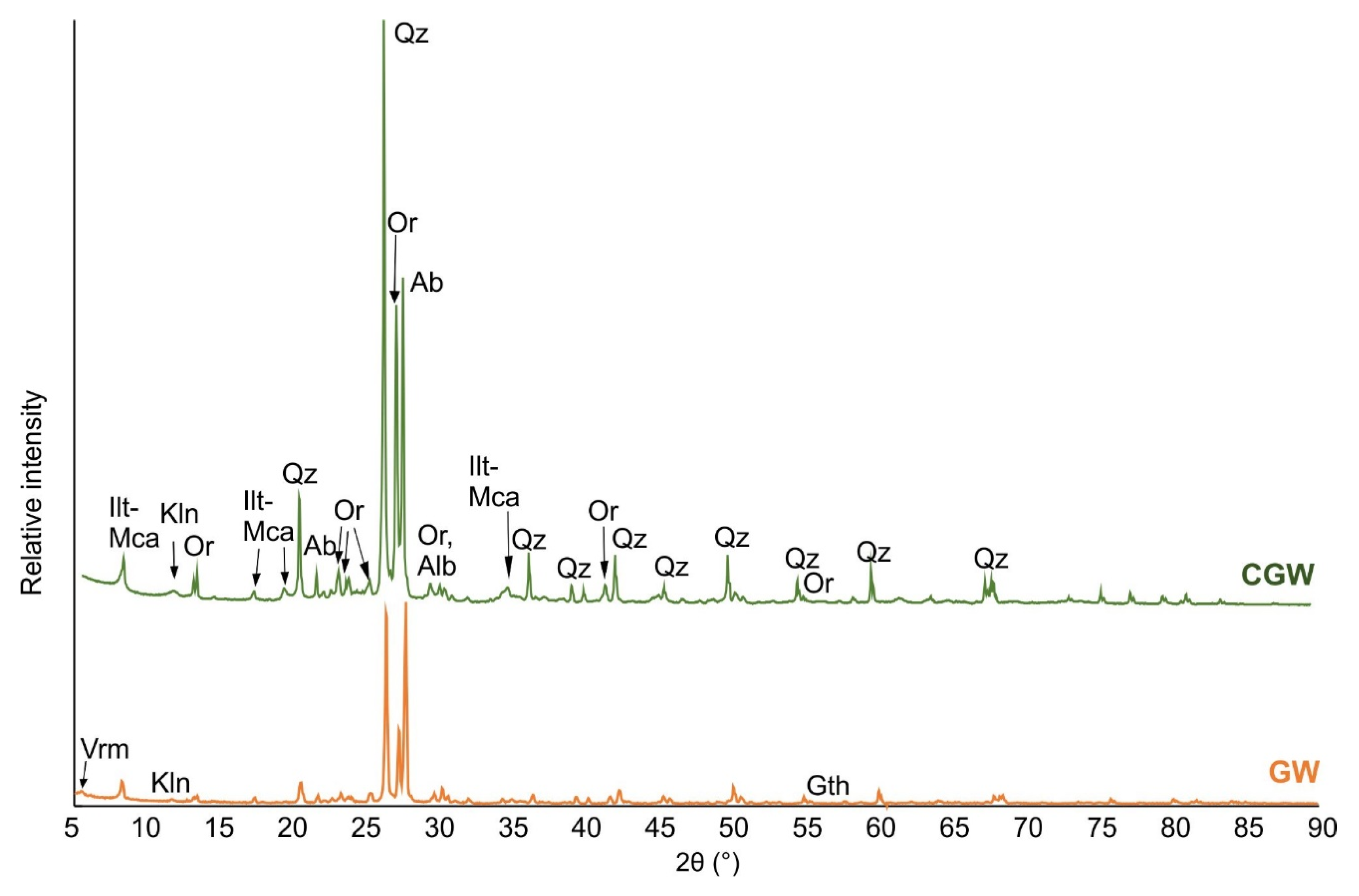

3.1. Characterization of Initial Materials

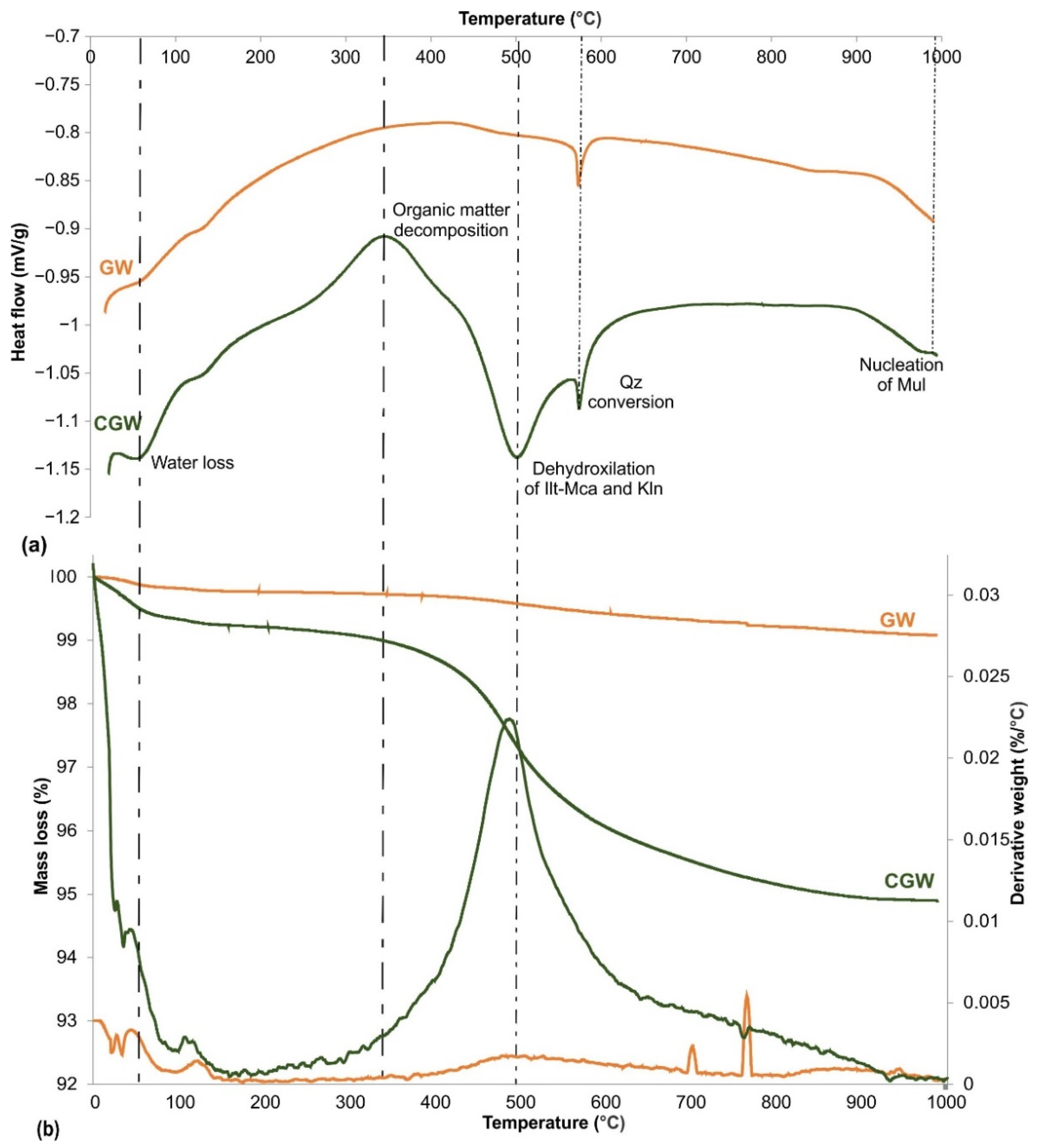

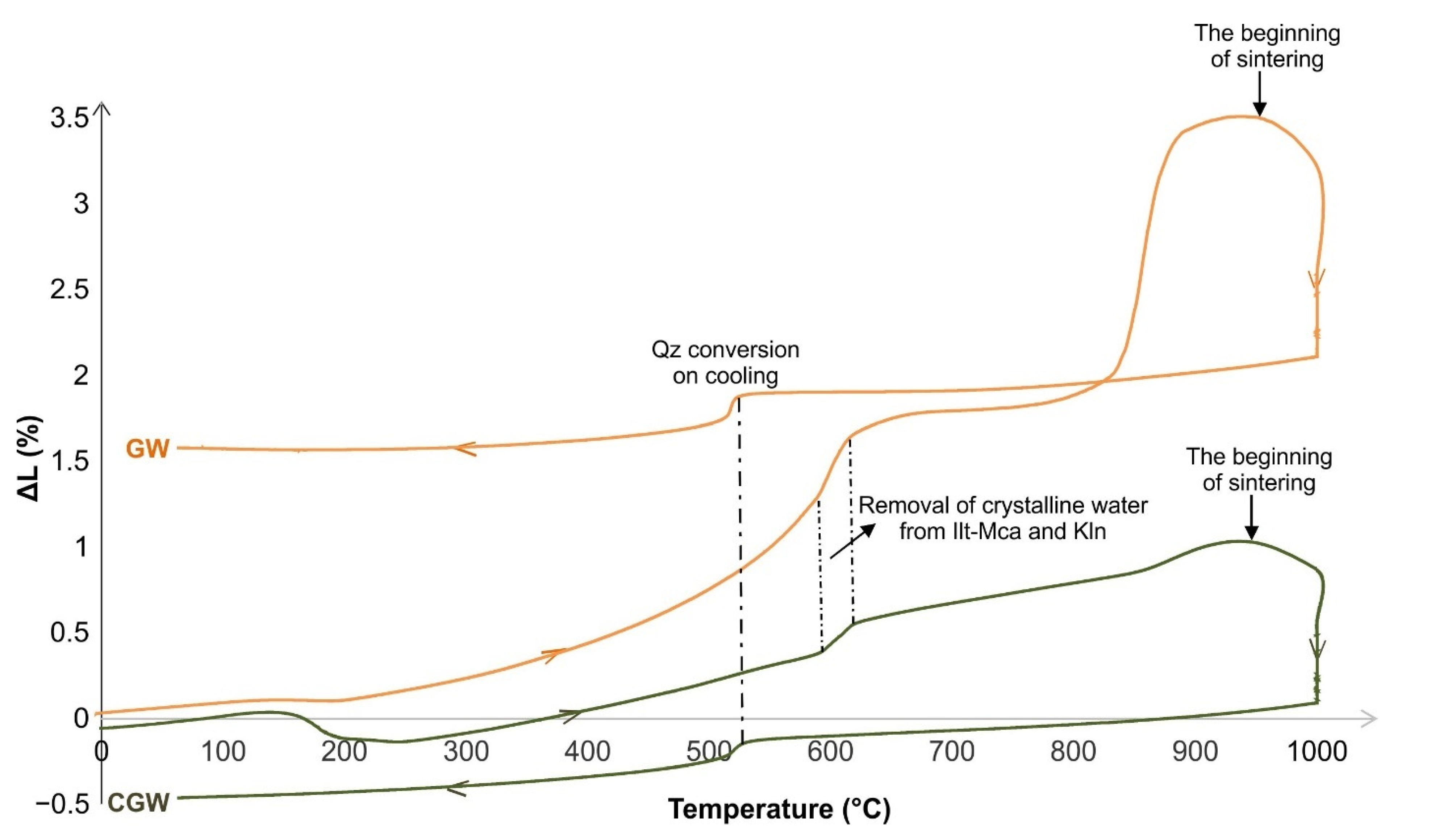

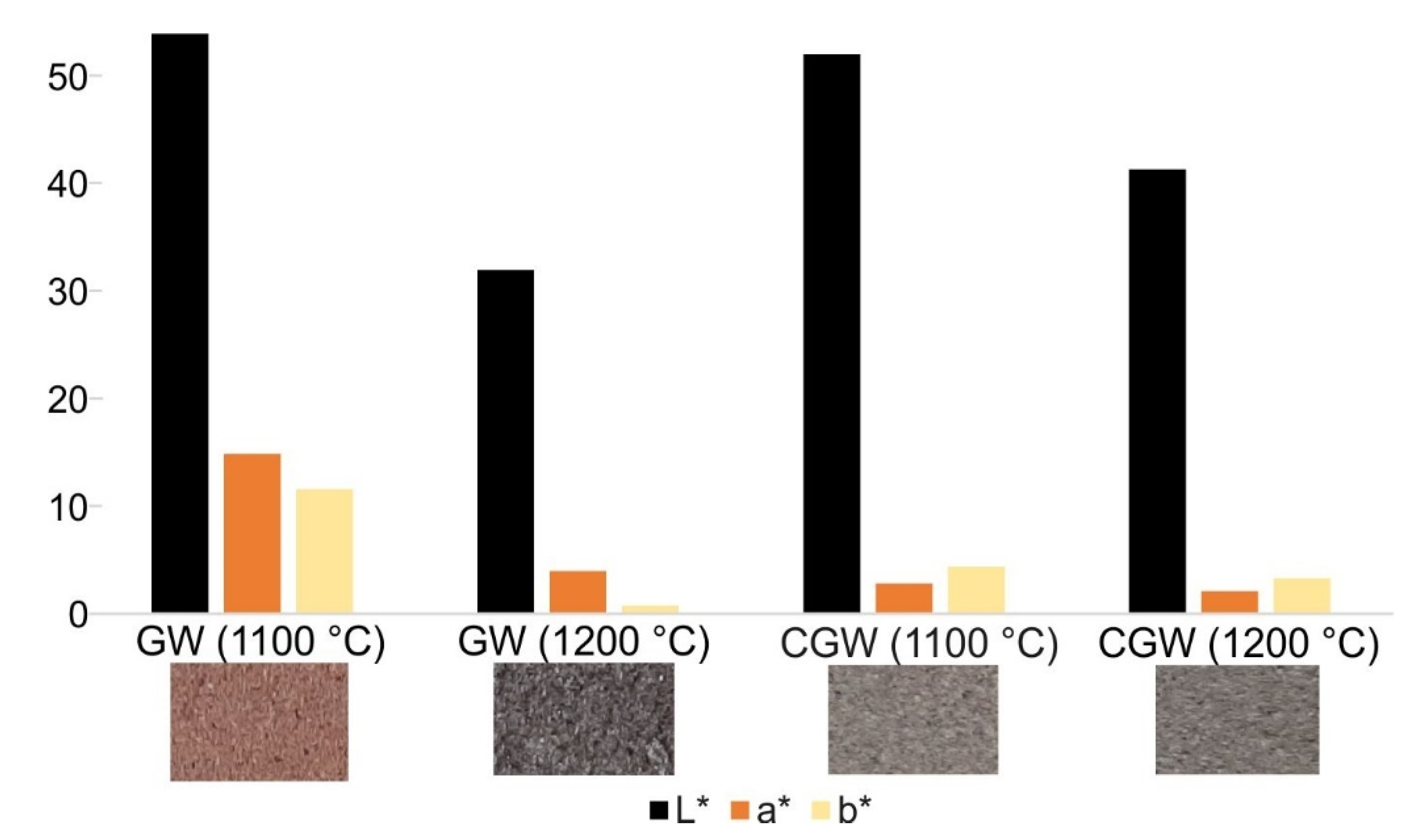

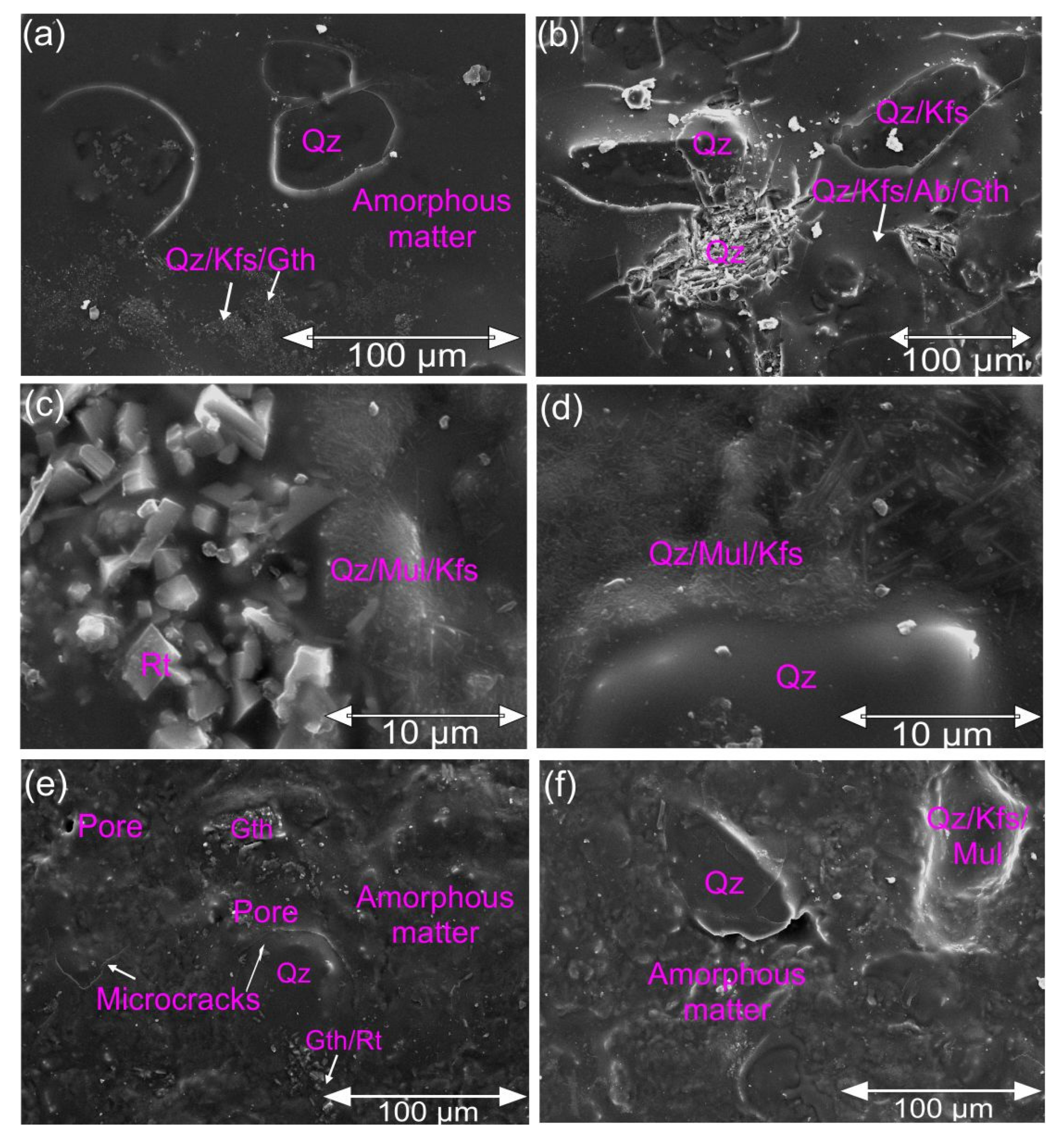

3.2. The Behavior in Shaping, Drying and Firing

3.3. The Characteristics of the Semi-Industrial Products

4. Conclusions

- The aplitic granite waste contains mainly feldspar (especially albite) and quartz and small amounts of micas and minor kaolinite. As such, the material is suitable as a filler and flux in ceramic batches by introducing feldspars and quartz. Since it lowers the plasticity of clay, it can be mixed with suitable raw materials of a decent quantity of clay minerals;

- Thermal analysis showed that the pure aplitic granite expands by raising the temperature, and significantly shrinks at the end of testing. This effect is mitigated by the addition of clay;

- The composite containing 40 mass% of the waste was of moderate plasticity and not susceptible to drying. A firing shrinkage of 2.2% was obtained;

- The samples fired both at 1200 and 1250 °C satisfied the requirements of the European standard concerning water absorption and modulus of rupture;

- The waste material is considered safe in terms of leaching of the trace elements.

- The composite material is observed to contain large quartz grains and a dense matrix interspersed with elongated crystals of mullite.

- The tiles are proven as freeze/thaw-resistant and not harmful to the environment in terms of lead and cadmium discharges;

- The semi-industrial probe turns out to meet all the requirements of the standards for unglazed tiles;

- The lowest obtained lightness of the tiles was found after firing at 1200 °C, and was lowered to about 41 when mixed with clay.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat Statistics Explained, Material Flow Accounts and Resource Productivity. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Material_flow_accounts_and_resource_productivity#Consumption_by_material_category (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Öztürk, Ç.; Akpınar, S.; Tarhan, M. Investigation of the usability of Sille stone as additive in floor tiles. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 57, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, M. Feldspathic fluxes for ceramics: Sources, production trends and technological value. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, M.; García-Ten, J.; Rambaldi, E.; Zanelli, C.; Vicent-Cabedo, M. Resource efficiency versus market trends in the ceramic tile industry: Effect on the supply chain in Italy and Spain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Tuğrul, A. Usability of granitic rock wastes as asphalt aggregate. In Proceedings of the International Conference Sustainable Aggregates Resource Management, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 20–22 September 2011; pp. 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shilar, F.A.; Quadri, S.S. Performance evaluation of interlocking bricks using granite waste powder. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dino, G.A.; Clemente, P.; Lasagna, M.; De Luca, D.A. Residual sludge from dimension stones: Characterisation for their exploitation in civil and environmental applications. Energy Procedia 2013, 40, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Abdelhaffez, G.S.; Ahmed, A.A. Potential use of marble and granite solid wastes as environmentally friendly coarse particulate in civil constructions. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 19, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, O.; Kucuk, A.; Akpinar, S. Effect of wollastonite addition on sintering of hard porcelain. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 5505–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, K.; Stefaniuk, D.; Sadowski, Ł.; Krzywiński, K.; Gicala, M.; Różańska, M. Potential use of granite waste sourced from rock processing for the application as coarse aggregate in high-performance self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter Junior, J.; Zaccaron, A.; Arcaro, S.; Neto, J.B.R.; de Noni Junior, A.; Pereira, F.R. Novel approach to ensure the dimensional stability of large-format enameled porcelain stoneware tiles through water absorption control. Open Ceram. 2022, 9, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ma, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Ceramic tiles derived from coal fly ash: Preparation and mechanical characterization. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 11953–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ma, S.; Zheng, S.; Chu, P.K. An eco-friendly and cleaner process for preparing architectural ceramics from coal fly ash: Pre-activation of coal fly ash by a mechanochemical method. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, M.; Guarini, G.; Conte, S.; Molinari, C.; Soldati, R.; Zanelli, C. Deposits, composition and technological behavior of fluxes for ceramic tiles. Period. Di Mineral. 2019, 88, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, P.; Manjate, R.S.; Quaresma, S.; Fernandes, H.R.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Development of ceramic floor tile compositions based on quartzite and granite sludges. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 4649–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.J.; Pinheiro, B.C.A.; Holanda, J.N.F. Processing of floor tiles bearing ornamental rock-cutting waste. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2010, 210, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadioli, M.C.B.; de Aguiar, M.C.; de Andrade Pazeto, M.; Monteiro, S.N. Influence of the granite waste into a clayey ceramic body for rustic wall tiles. Mater. Sci. Forum 2012, 727–728, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.J.M.; Sousa, A.R.O.; Macedo, D.A.; Dutra, R.P.S.; Campos, L.F.A. Effects of granite waste addition on the technological properties of industrial silicate based-ceramics. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 125205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngayakamo, B.; Bello, A.; Onwualu, A.P. Development of eco-friendly fired clay bricks incorporated with granite and eggshell wastes. Environ. Chall. 2020, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Fernandes, H.R.; Olhero, S.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Incorporation of wastes from granite rock cutting and polishing industries to produce roof tiles. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 29, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maghraby, A.; ElMaaty, M.A.A.; Khater, G.A.; Mostafa, N.Y. Utilization of grantitoid rocks in Taif area as raw materials in ceramic bodies. J. Am. Sci. 2010, 6, 691–701. [Google Scholar]

- Poznyak, A.I.; Levitskii, I.A.; Barantseva, S.E. Basaltic and granitic rocks as components of ceramic mixes for interior wall tiles. Glass Ceram. 2012, 69, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaied, M.E.; Gallala, W.; Essefi, E.; Montacer, M. Microstructural and mechanical properties in traditional ceramics as a function of quartzofeldspathic sand incorporation. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2011, 70, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbický, T.; Přikryl, R. Recovery of some critical raw materials from processing waste of feldspar ore related to hydrothermally altered granite: Laboratory-scale beneficiation. Minerals 2021, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dino, G.A.; Fornaro, M.; Trentin, A. Quarry waste: Chances of a possible economic and environmental valorisation of the Montorfano and Baveno granite disposal sites. J. Geol. Res. 2012, 2012, 452950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simić, V.; Životić, D.; Miladinović, Z. Towards better valorisation of industrial minerals and rocks in Serbia—Case study of industrial clays. Resources 2021, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, R.R.; Navarro, L.; Santana, L.; Neves, G.A.; Ferreira, H.C. Recycling of Mine Wastes as Ceramic Raw Materials: An Alternative to Avoid Environmental Contamination. In Environmental Contamination; Srivastava, J., Ed.; InTech Open: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vasić, M.V.; Pezo, L.; Vasić, M.R.; Mijatović, N.; Mitrić, M.; Radojević, Z. What is the most relevant method for water absorption determination in ceramic tiles produced by illitic-kaolinitic clays? The mystery behind the gresification diagram. Bol. Soc. Esp. Cerám. V. 2020; in press. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenović, M.; Pezo, L.; Mančić, L.; Radojević, Z. Thermal and mineralogical characterization of loess heavy clays for potential use in brick industry. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 580, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S. Accurate quantitative analysis of clay and other minerals in sandstones by XRD: Comparison of a Rietveld and reference intensity ratio (RIR) method and the importance of sample preparation. Clay Miner. 2000, 35, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, M.V.; Terzić, A.; Radovanović, Ž.; Radojević, Z.; Warr, L.N. Alkali-activated geopolymerization of a low illitic raw clay and waste brick mixture. An alternative to traditional ceramics. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 218, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, M.V.; Goel, G.; Vasić, M.; Radojević, Z. Recycling of waste coal dust for the energy-efficient fabrication of bricks: A laboratory to industrial-scale study. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-3; Ceramic Tiles—Part 3: Determination of Water Absorption, Apparent Porosity, Apparent Relative Density and Bulk Density. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018.

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-4; Ceramic Tiles—Part 4: Determination of Modulus of Rupture and Breaking Strength. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019.

- SRPS EN 993-12; Methods of Test for Dense Shaped Refractory Products—Part 12: Determination of Pyrometric Cone Equivalent (Refractoriness). Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 1997.

- Tossavainen, M. Leaching Behavior of Rock Materials and a Comparison with Slag Used in Road Construction. Ph.D. Thesis, Division of Mineral Processing, Department of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Haiying, Z.; Youcai, Z.; Jingyu, Q. Study on use of MSWI fly ash in ceramic tile. J. Haz. Mat. 2007, 141, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-15; Ceramic Tiles—Part 15: Determination of Lead and Cadmium Given Off by Tiles. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021.

- Kurešević, L. Tertiary plutonic rocks of central and western Serbia Vardar zone as dimension stone. Acta Montan. Slovaca Ročník 2013, 18, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, L.N. IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols. Miner. Mag. 2021, 85, 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavay, J.; Jonas, K.; Elek, S.; Inczedy, J. Characterization of the particle size and the crystallinity of certain minerals by IR spectrophotometry and other instrumental methods-II. Investigations on quartz and feldspar. Clay. Clay Miner. 1978, 26, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaretti, M.G.; Ninago, M.D.; Paulo, C.I.; Petit, H.A.; Irassarc, E.F.; Vega, D.A.; Villar, M.A.; López, O.V. Biocomposites Based on Thermoplastic Starch and Granite Sand Quarry Waste; Tech Science Press, JRM: Henderson, NV, USA, 2019; p. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theodosoglou, E.; Koroneos, A.; Soldatos, T.; Zorba, T.; Paraskevopoulos, K.M. Comparative Fourier transform infrared and X-ray powder diffraction analysis of naturally occurred K-feldspars. Bull. Geol. Soc. G. 2010, 43, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zanelli, C.; Conte, S.; Molinari, C.; Soldati, R.; Dondi, M. Waste recycling in ceramic tiles: A technological outlook. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-2; Ceramic Tiles—Part 2: Determination of Dimensions and Surface Quality. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019.

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-6; Ceramic Tiles—Part 6: Determination of Resistance to Deep Abrasion for Unglazed Tiles. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015.

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-8; Ceramic Tiles—Part 8: Determination of Linear Thermal Expansion. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015.

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-12; Ceramic Tiles—Part 12: Determination of Frost Resistance. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2012.

- SRPS EN ISO 10545-13; Ceramic Tiles—Part 13: Determination of Chemical Resistance. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017.

- SRPS EN 14411; Ceramic Tiles—Definition, Classification, Characteristics Assessment and Verification of Constancy of Performance and Marking. Institute for Standardization of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017.

| Parameter (mass%) | GW | CGW |

|---|---|---|

| LOI 1 | 1.10 ± 0.20 | 3.52 ± 0.30 |

| SiO2 | 71.76 ± 0.50 | 65.96 ± 0.40 |

| Al2O3 | 14.42 ± 0.40 | 20.59 ± 0.45 |

| TiO2 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.61 ± 0.10 |

| Fe2O3 | 1.54 ± 0.25 | 1.36 ± 0.30 |

| CaO | 1.36 ± 0.20 | 0.52 ± 0.10 |

| MgO | 0.76 ± 0.20 | 1.36 ± 0.25 |

| Na2O | 3.57 ± 0.20 | 2.18 ± 0.10 |

| K2O | 4.65 ± 0.25 | 3.60 ± 0.30 |

| SO3 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| P2O5 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

| MnO | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Total carbonates contents | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Clay < 0.002 mm | 3 ± 0.6 | 16 ± 0.6 |

| Alevrolite 0.002 mm < particles < 0.06 mm | 37 ± 0.6 | 54 ± 0.6 |

| Sand > 0.06 mm | 60 ± 0.6 | 30 ± 0.0 |

| Remains on the 0.063 mm sieve | 56.37 ± 0.58 | 31.86 ± 0.58 |

| Element (mg/kg) | GW | CGW |

|---|---|---|

| Pb | 10.2 ± 0.1 | 18.7 ± 0.2 |

| Cd | <0.2 | <0.2 |

| Hg | <0.2 | <0.2 |

| Cr | 35.8 ± 0.1 | 29.2 ± 0.0 |

| Cu | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| Zn | 40.0 ± 0.2 | 39.0 ± 0.2 |

| Ba | 220 ± 0.4 | 167 ± 0.3 |

| Ni | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.2 |

| As | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| Re | <0.2 | <0.2 |

| Phase 1 (mass%) | GW (mass%) | CGW (mass%) |

|---|---|---|

| Albite (Ab) | 38.5 | 15.4 |

| Orthoclase (Or) | 23.3 | 11.6 |

| Quartz (Qz) | 23.2 | 47.8 |

| Illite-mica (Ilt-mca) | 10.3 | 19.6 |

| Kaolinite (Kln) | 2.0 | 4.4 |

| Dolomite (Dol) | 1.2 | 0.5 |

| Vermiculite (Ver) | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Goethite (Gth) | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Dry Samples | Fired Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile Size (mm2) | Drying Shrinkage (%) | Modulus of Rupture (MPa) | Firing Temp. (°C) | Firing Shrinkage (%) | Bulk Density (g/cm3) | Loss on Ignition (%) | Water Absorption (%) | Modulus of Rupture (MPa) |

| 25 × 120 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 1100 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 1.87 ± 0.12 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 12.01 ± 0.11 | 11.93 ± 0.15 |

| 1200 | 6.26 ± 0.08 | 2.10 ± 0.15 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 18.02 ± 0.18 | |||

| 50 × 120 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 1100 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 1.87 ± 0.11 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 14.85 ± 0.12 | 11.46 ± 0.14 |

| 1200 | 6.06 ± 0.08 | 2.08 ± 0.13 | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 18.56 ± 0.18 | |||

| Dry Samples | Fired Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile Size (mm2) | Drying Shrinkage (%) | Modulus of Rupture (MPa) | Firing Temp. (°C) | Firing Shrinkage (%) | Bulk Density (g/cm3) | Loss on Ignition (%) | Water Absorption (%) | Modulus of Rupture (MPa) |

| 25 × 120 | −0.63 ± 0.03 | 1.13 ± 0.05 | 1200 | 3.72 ± 0.07 | 2.27 ± 0.18 | 3.56 ± 0.07 | 2.42 ± 0.08 | 28.15 ± 0.11 |

| 1250 | 2.22 ± 0.06 | 2.06 ± 0.09 | 3.77 ± 0.07 | 1.30 ± 0.09 | 28.85 ± 0.10 | |||

| 50 × 120 | −0.54 ± 0.03 | 1.17 ± 0.04 | 1200 | 3.56 ± 0.05 | 2.23 ± 0.17 | 3.49 ± 0.06 | 2.50 ± 0.09 | 28.24 ± 0.09 |

| 1250 | 2.24 ± 0.06 | 2.17 ± 0.15 | 3.87 ± 0.06 | 1.33 ± 0.10 | 28.68 ± 0.09 | |||

| Property Tested | Sample Firing Temperature | Average Results |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions [45] | 1200 °C | 48.53 × 116.19 mm2 |

| 1250 °C | 48.90 × 116.84 mm2 | |

| Thickness [45] | 1200 °C | 6.9 mm |

| 1250 °C | 7.0 mm | |

| Surface quality [45] | 1200 °C | 100% of tiles without defects |

| 1250 °C | 100% of tiles without defects | |

| Water absorption [33] | 1200 °C | 2.46% |

| 1250 °C | 1.40% | |

| Bending strength [34] | 1200 °C | 804.4 N |

| 1250 °C | 798.7 N | |

| Modulus of rupture [34] | 1200 °C | 28.24 MPa |

| 1250 °C | 28.33 MPa | |

| Deep abrasion [46] | 1200 °C | 225 mm3 |

| 1250 °C | 225 mm3 | |

| Linear thermal expansion [47] | 1200 °C | 0.390 mm/m |

| 1250 °C | 0.380 mm/m | |

| Freeze/thaw resistance [48] | 1200 °C | E1 = 2.27%, E1 = 2.39%; no defects |

| 1250 °C | E1 = 1.29%, E1 = 1.32%; no defects | |

| Chemical resistance [49] | 1200 °C | Class A |

| 1250 °C | Class A | |

| Pb and Cd [38] | 1200 °C | <0.03 mg/L and <0.01 mg/L |

| 1250 °C | <0.03 mg/L and <0.01 mg/L |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasić, M.V.; Mijatović, N.; Radojević, Z. Aplitic Granite Waste as Raw Material for the Production of Outdoor Ceramic Floor Tiles. Materials 2022, 15, 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093145

Vasić MV, Mijatović N, Radojević Z. Aplitic Granite Waste as Raw Material for the Production of Outdoor Ceramic Floor Tiles. Materials. 2022; 15(9):3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093145

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasić, Milica Vidak, Nevenka Mijatović, and Zagorka Radojević. 2022. "Aplitic Granite Waste as Raw Material for the Production of Outdoor Ceramic Floor Tiles" Materials 15, no. 9: 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093145

APA StyleVasić, M. V., Mijatović, N., & Radojević, Z. (2022). Aplitic Granite Waste as Raw Material for the Production of Outdoor Ceramic Floor Tiles. Materials, 15(9), 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093145