Dynamic Thermal Response of Multiple Interface Cracks between a Half-Plane and a Coating Layer under General Transient Temperature Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

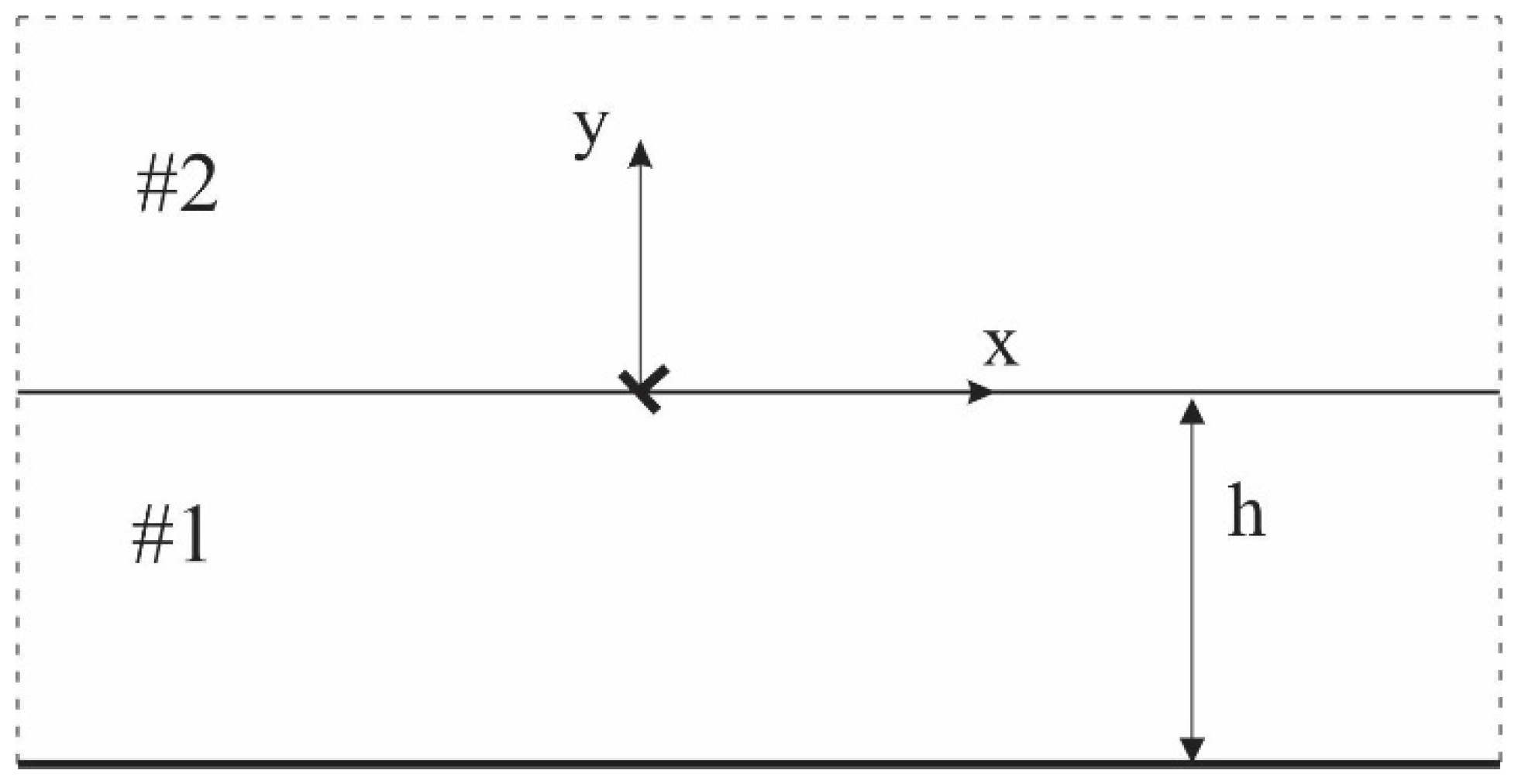

2. Formulation of the Problem

2.1. Intact Half-Plane with a Thermal Coating under the Disturbance of a Single Thermal Dislocation

2.2. Solution for the Intact Half-Plane with a Thermal Coating under General Thermal Loading

2.3. Integral Equations for the Interface Crack Problem of the Half-Plane with a Thermal Coating

3. Results and Discussion

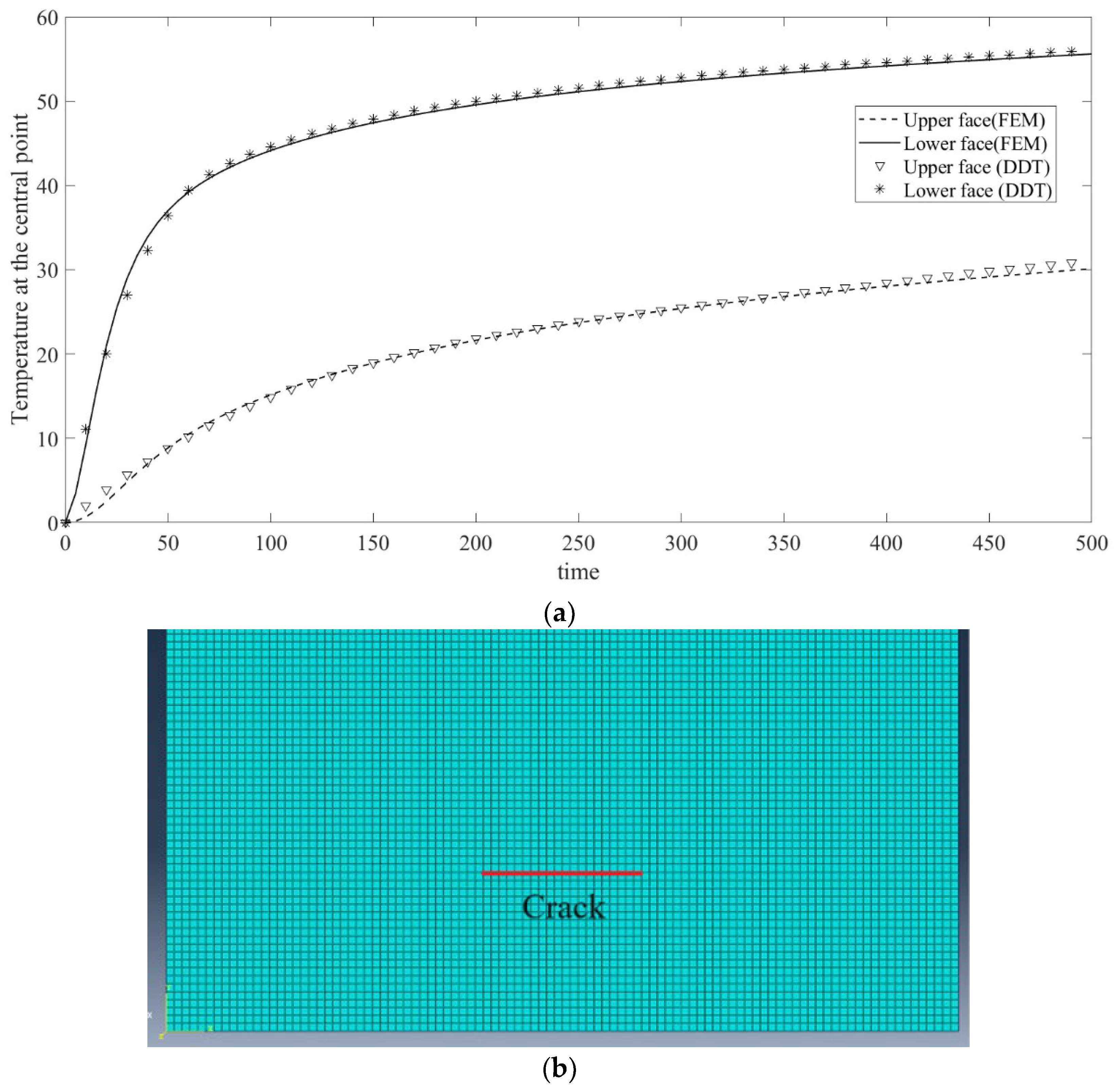

3.1. Finite Element Verification

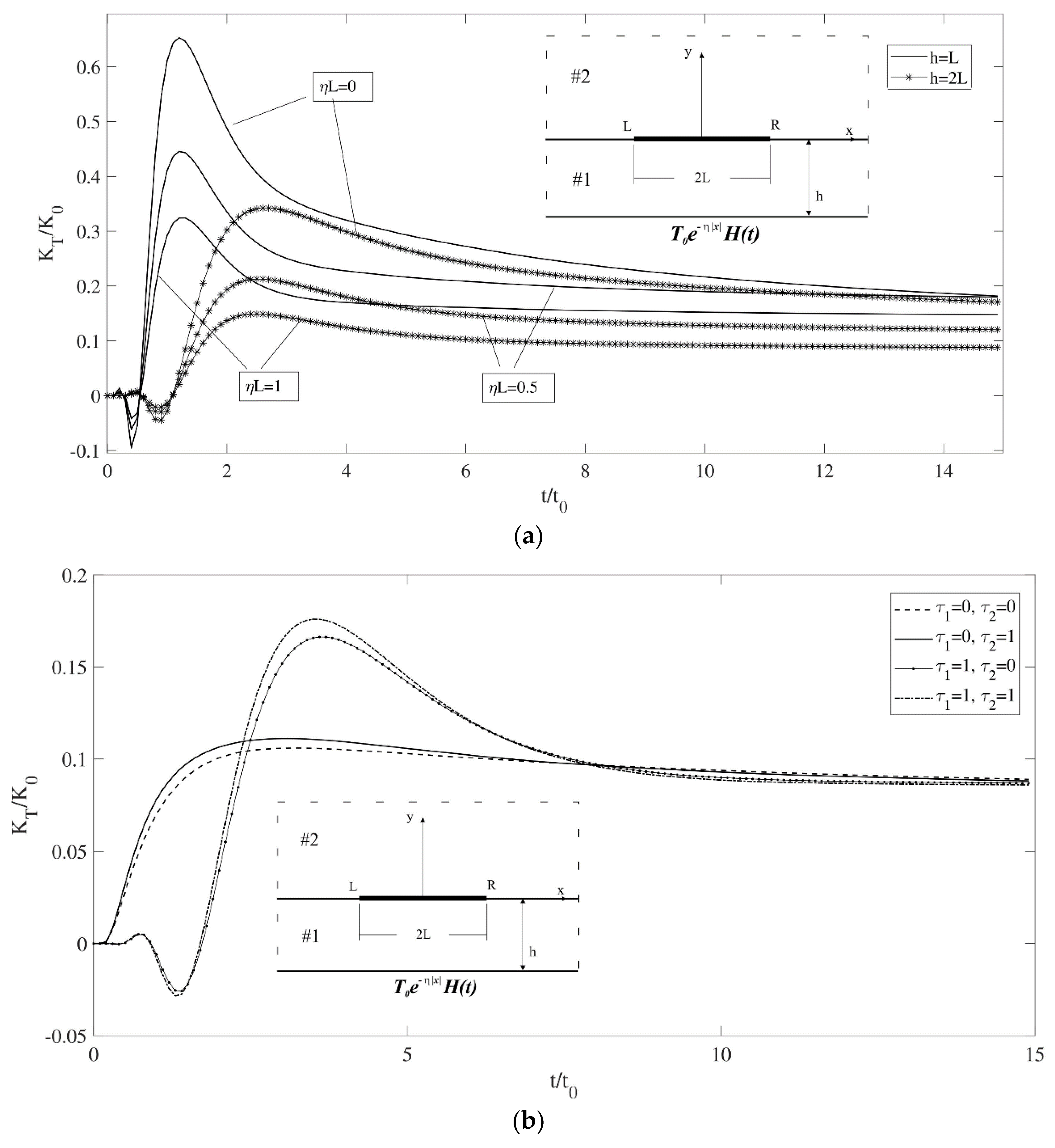

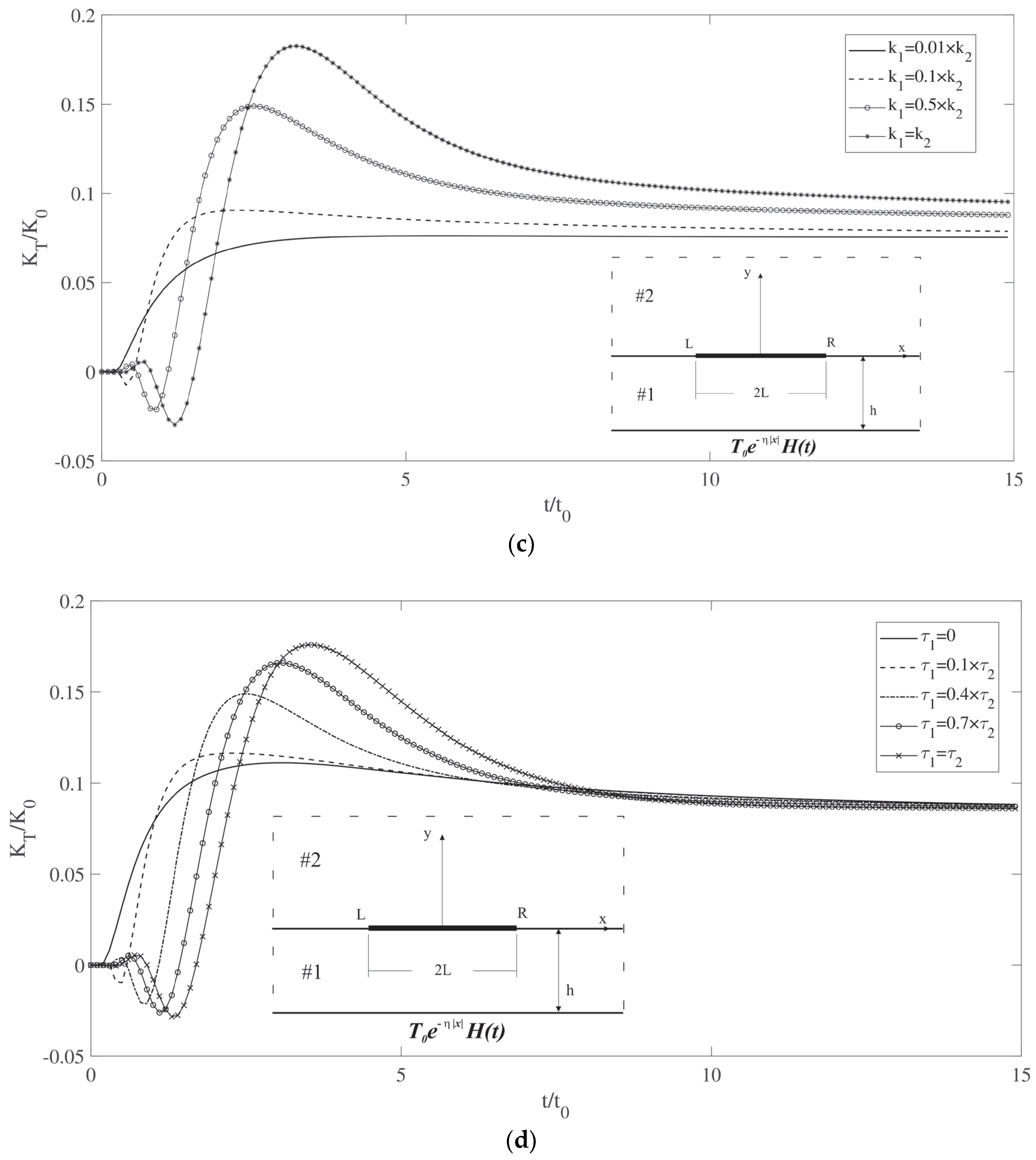

3.2. Single-Interface-Crack Problem

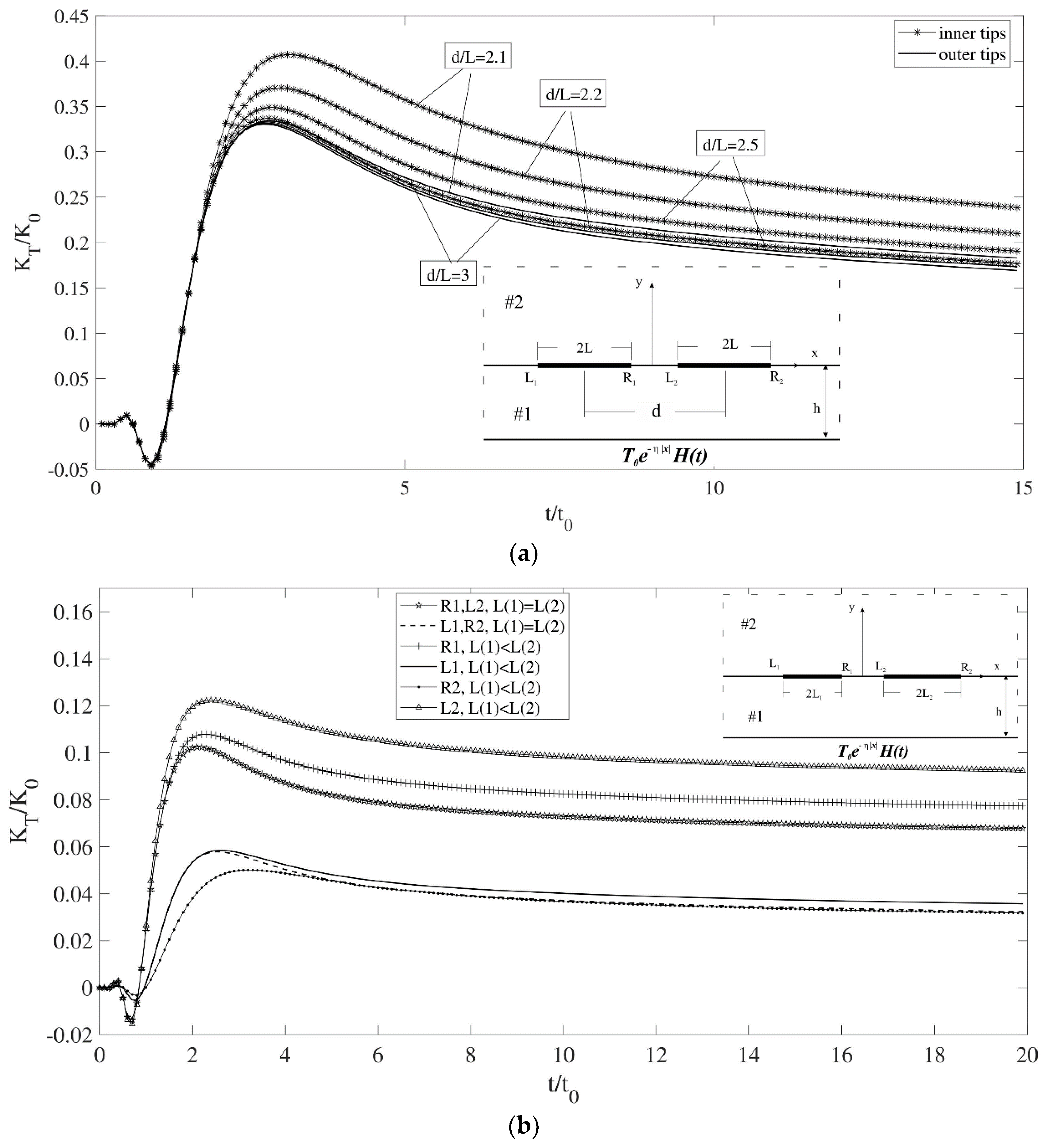

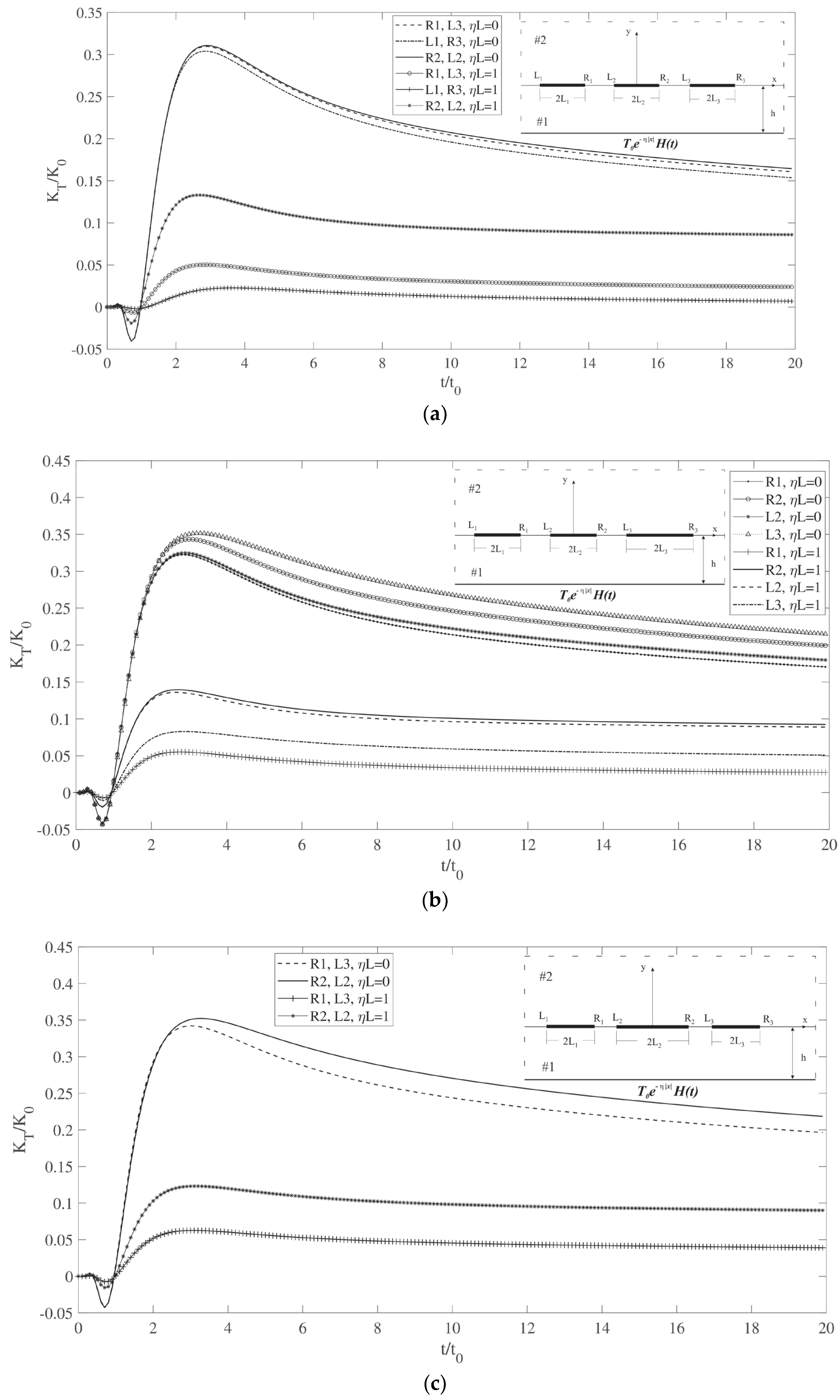

3.3. Multiple-Interface-Crack Problem

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Unknown coefficients of temperature caused by one dislocation | |

| Temperature discontinuity | |

| Dislocation densities | |

| c | Specific heat |

| Unknown coefficients of temperature in the intact medium | |

| Vertical distance between the interface and the boundary | |

| Heaviside step function | |

| k | Thermal conductivity |

| Kernels of integral equations | |

| Mode I stress intensity factor for the left and right crack tips | |

| Half-lengths of the crack | |

| Number of cracks | |

| p,q | Collocation points of Chebyshev polynomials |

| Laplace transform parameter | |

| t | Time |

| Temperature gradient in the y direction | |

| Temperature | |

| Roots of the characteristic equation | |

| Dirac delta function | |

| Loading parameter | |

| Mass density | |

| Relaxation time | |

| Fourier transform parameter |

Appendix A

References

- Chen, Z.; Akbarzadeh, A. Advanced Thermal Stress Analysis of Smart Materials and Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khairy, R.T.; Al-Ofey, Z.M. Analytical Solution of the Hyperbolic Heat Conduction Equation for Moving Semi-Infinite Medium under the Effect of Time-Dependent Laser Heat Source. J. Appl. Math. 2009, 2009, 604695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, D.Y. The singular behavior of the temperature gradient in the vicinity of a macrocrack tip. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1990, 33, 2625–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaki, P. Key Features of Analytical Solutions for Hyperbolic Heat Conduction. J. Therm. Eng. 1995, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, M.; Malinowski, L. Hyperbolic heat conduction in the semi-infinite body with the heat source which capacity linearly depends on temperature. Heat Mass Transf. 1998, 33, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocłoń, P.; Łopata, S. Hyperbolic Heat Conduction Equation. In Encyclopedia of Thermal Stresses; Hetnarski, R.B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.T.; Hu, K.Q. Hyperbolic Heat Conduction in a Cracked Thermoelastic Half-Plane Bonded to a Coating. Int. J. Thermophys. 2012, 33, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J. A crack in a finite medium under transient non-Fourier heat conduction. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 4631–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Chen, Z. Transient heat conduction analysis of a cracked half-plane using dual-phase-lag theory. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 62, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.W.; Hu, K.Q.; Qian, L.F.; Chen, Z.T. Non-Fourier Heat Conduction of a Functionally Graded Cylinder Containing a Cy-lindrical Crack. Adv. Math. Phys. 2020, 2020, 8121295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hou, C.; Zhao, M.; Wan, X. A peridynamic model for non-Fourier heat transfer in orthotropic plate with uninsulated cracks. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 115, 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.T.; Hu, K.Q. Thermo-Elastic Analysis of a Cracked Half-Plane Under a Thermal Shock Impact Using the Hyperbolic Heat Conduction Theory. J. Therm. Stress. 2012, 35, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, J. Hyperbolic heat conduction and associated transient thermal fracture for a piezoelectric material layer. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013, 50, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.M.; Wang, B.L. Transient thermal elastic fracture of a piezoelectric cylinder specimen. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2012, 83, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravandi, M.; Fariborz, S. Thermo-elastic dislocation with application to crack problems. Eur. J. Mech.—A/Solids 2013, 38, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafa, J.P.; Fariborz, S.J. Analysis of cracked layers under transient temperature field. J. Therm. Stress. 2018, 41, 658–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Schiavone, P. A finite crack in a half-plane under uniform heat flux or surface heat source. J. Therm. Stress. 2021, 44, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Nourazar, M.; Chen, Z.T.; Hu, K.; Zhang, X. Dynamic response of a cracked thermopiezoelectric strip under thermo-electric loading using fractional heat conduction. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 103, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Pourasghar, A.; Chen, Z.T.; Zhang, X. Non-Fourier thermoelastic interaction of two collinear cracks in a func-tionally graded layer. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 122, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.R.; Kokini, K. Transient thermoelastic fracture of interface cracks: Effect of bending restraints. Int. J. Fract. 1992, 54, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Chang, R. Steady-state heat conduction problem of the interface crack between dissimilar anisotropic media. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1993, 36, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, R.; Kishen, J.C. The use of conservative integral in bi-material interface crack problems subjected to thermal loads. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2008, 45, 2976–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-H.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Li, X. Interface crack problem in layered orthotropic materials under thermo-mechanical loading. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2014, 51, 4221–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, Z.T.; Li, X.F. Non-Fourier fractional heat conduction in two bonded dissimilar materials with a penny-shaped in-terface crack. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 140, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinović, S.; Djoković, J.; Nikolić, R.; Hadzima, B. Thermal fracture characteristics of an interface crack subjected to tem-perature variations. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2020, 26, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Lv, Z.; Liu, H.; Jing, F.; Wang, R. Analysis of interfacial crack initiation mechanism of thermal barrier coatings in isothermal oxidation process based on interfacial stress state. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 10287–10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z. Thermal and fracture analysis of collinear interface cracks in graded coating systems under ramp-type heating. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 216, 124581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, F.; Gupta, G.D.; Cook, T.S. Numerical solution of singular integral equations. In Methods of Analysis and Solutions of Crack Problems, Mechanics of Fracture; Sih, G.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1973; Volume 1, pp. 368–425. [Google Scholar]

- Stehfest, H. Algorithm 368: Numerical inversion of Laplace transforms [D5]. Commun. ACM 1970, 13, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nourazar, M.; Yang, W.; Chen, Z. Dynamic Thermal Response of Multiple Interface Cracks between a Half-Plane and a Coating Layer under General Transient Temperature Loading. Materials 2024, 17, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112478

Nourazar M, Yang W, Chen Z. Dynamic Thermal Response of Multiple Interface Cracks between a Half-Plane and a Coating Layer under General Transient Temperature Loading. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112478

Chicago/Turabian StyleNourazar, Mahsa, Weilin Yang, and Zengtao Chen. 2024. "Dynamic Thermal Response of Multiple Interface Cracks between a Half-Plane and a Coating Layer under General Transient Temperature Loading" Materials 17, no. 11: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112478

APA StyleNourazar, M., Yang, W., & Chen, Z. (2024). Dynamic Thermal Response of Multiple Interface Cracks between a Half-Plane and a Coating Layer under General Transient Temperature Loading. Materials, 17(11), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112478