The Effect of Cr Addition on the Strength and High Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Mo Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

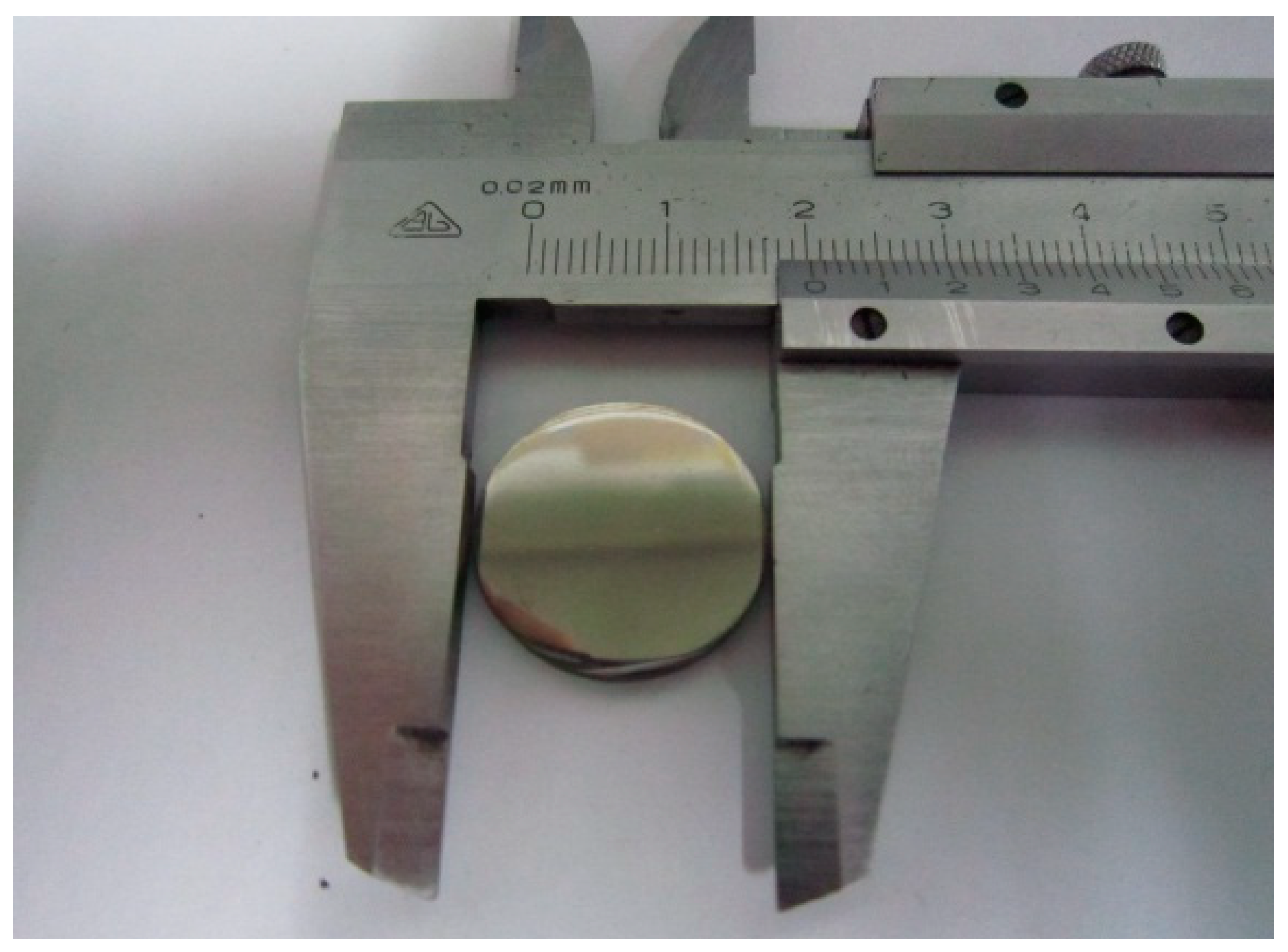

2. Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

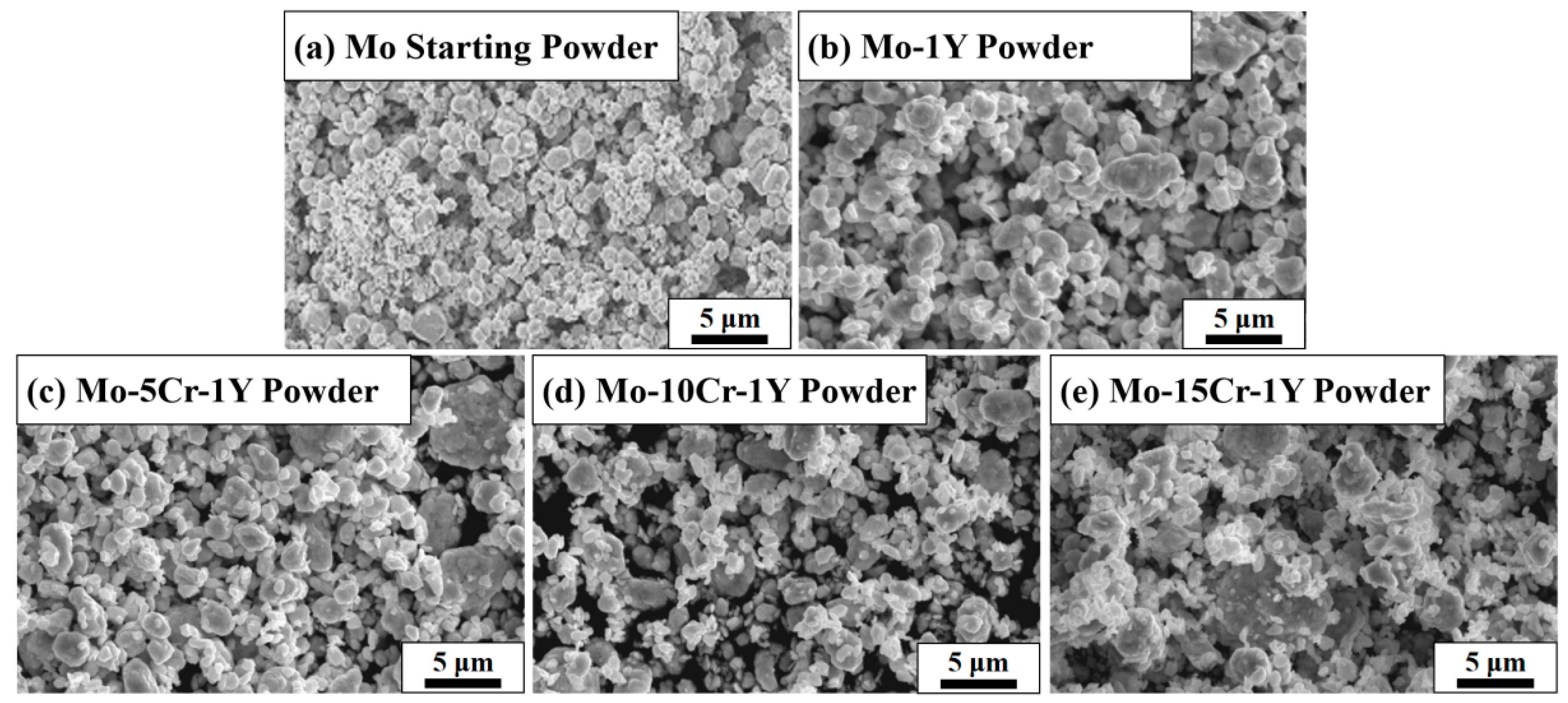

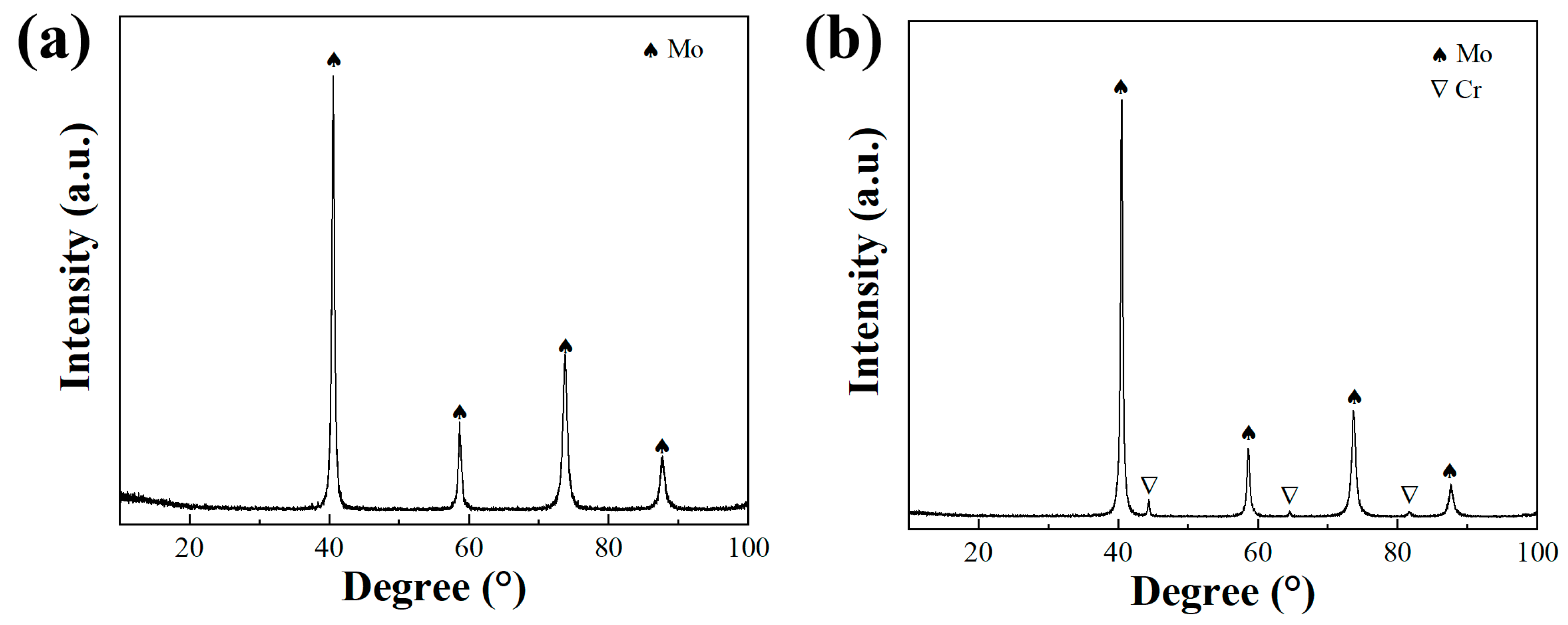

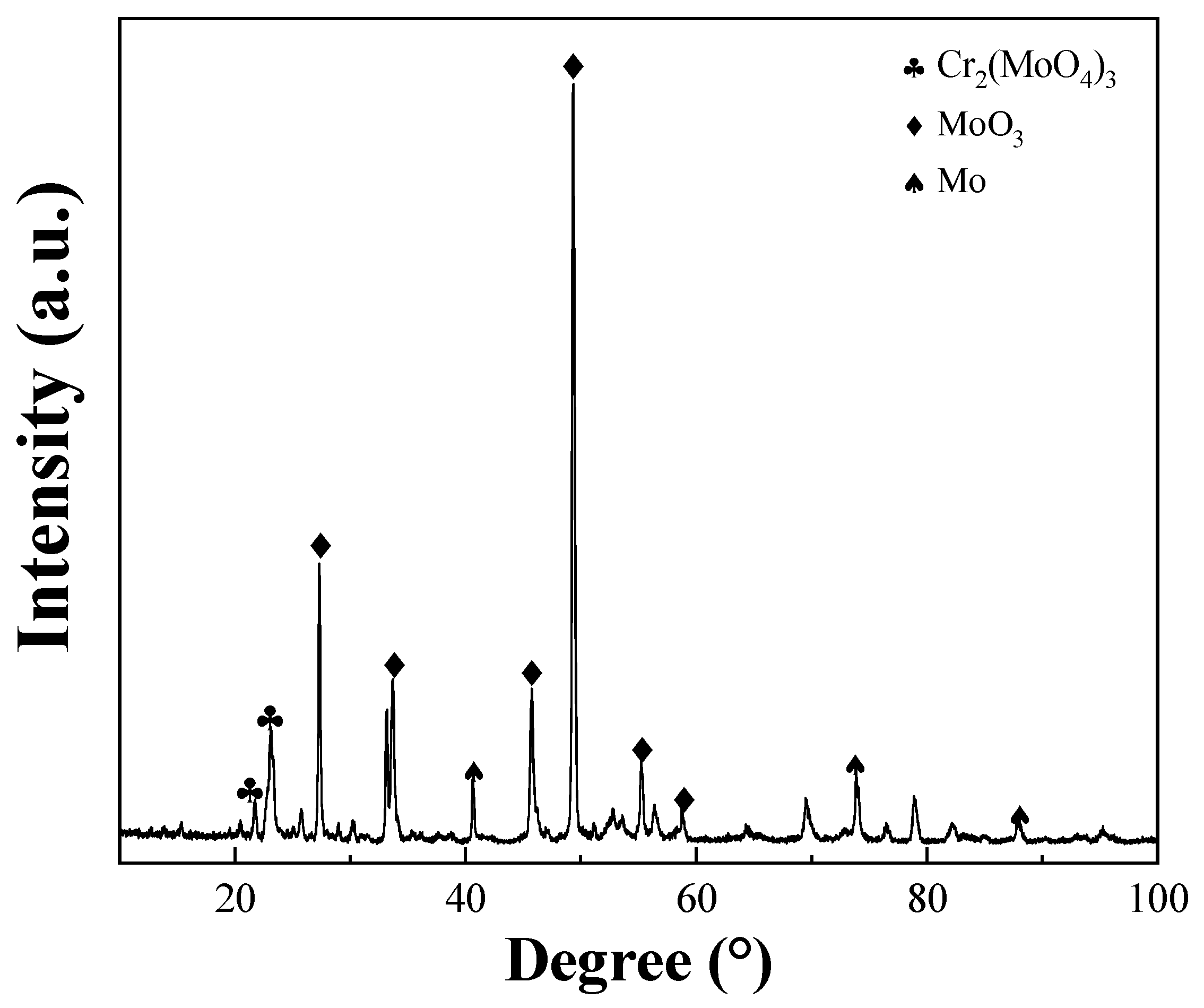

3.1. The Morphology and Phase of as-Milled Powders

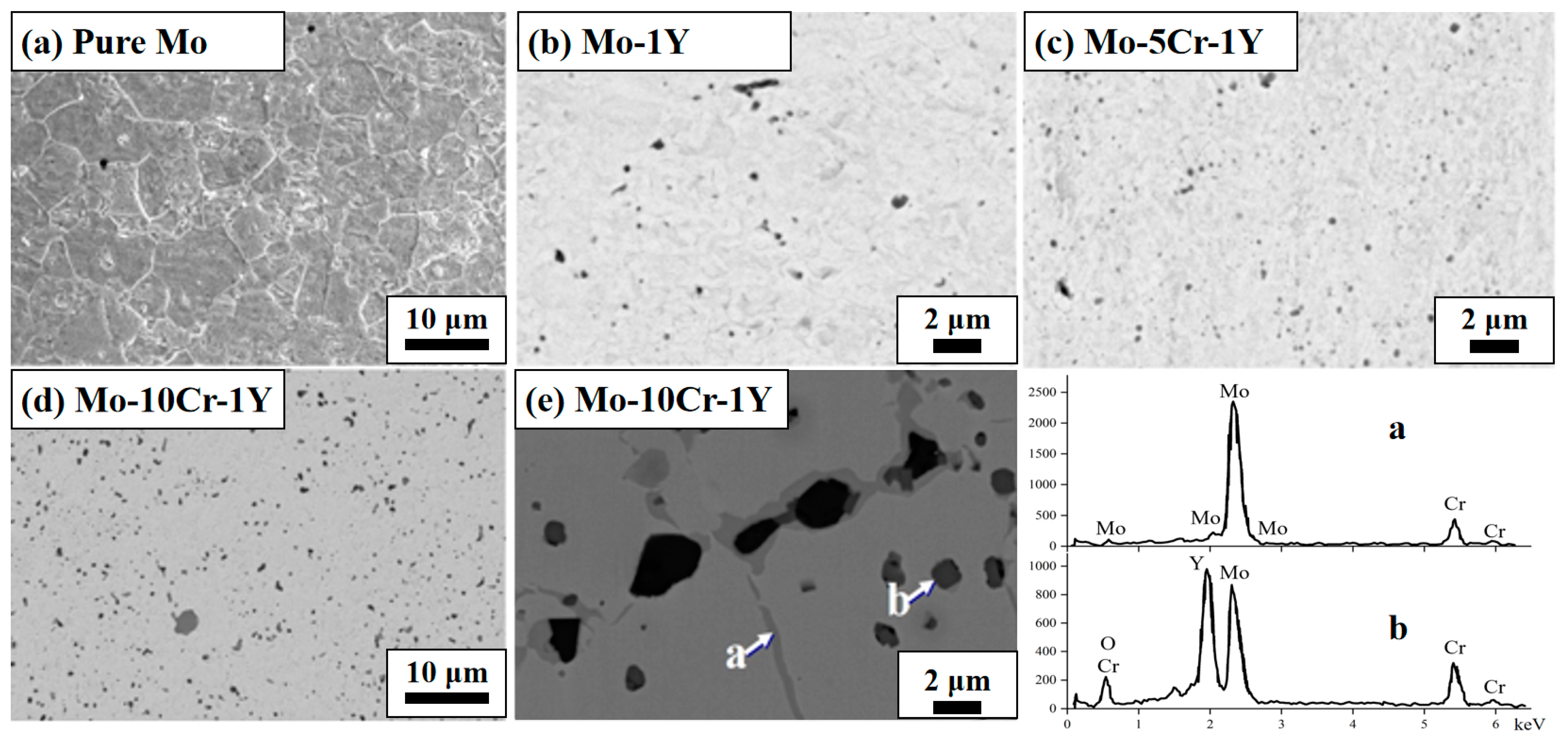

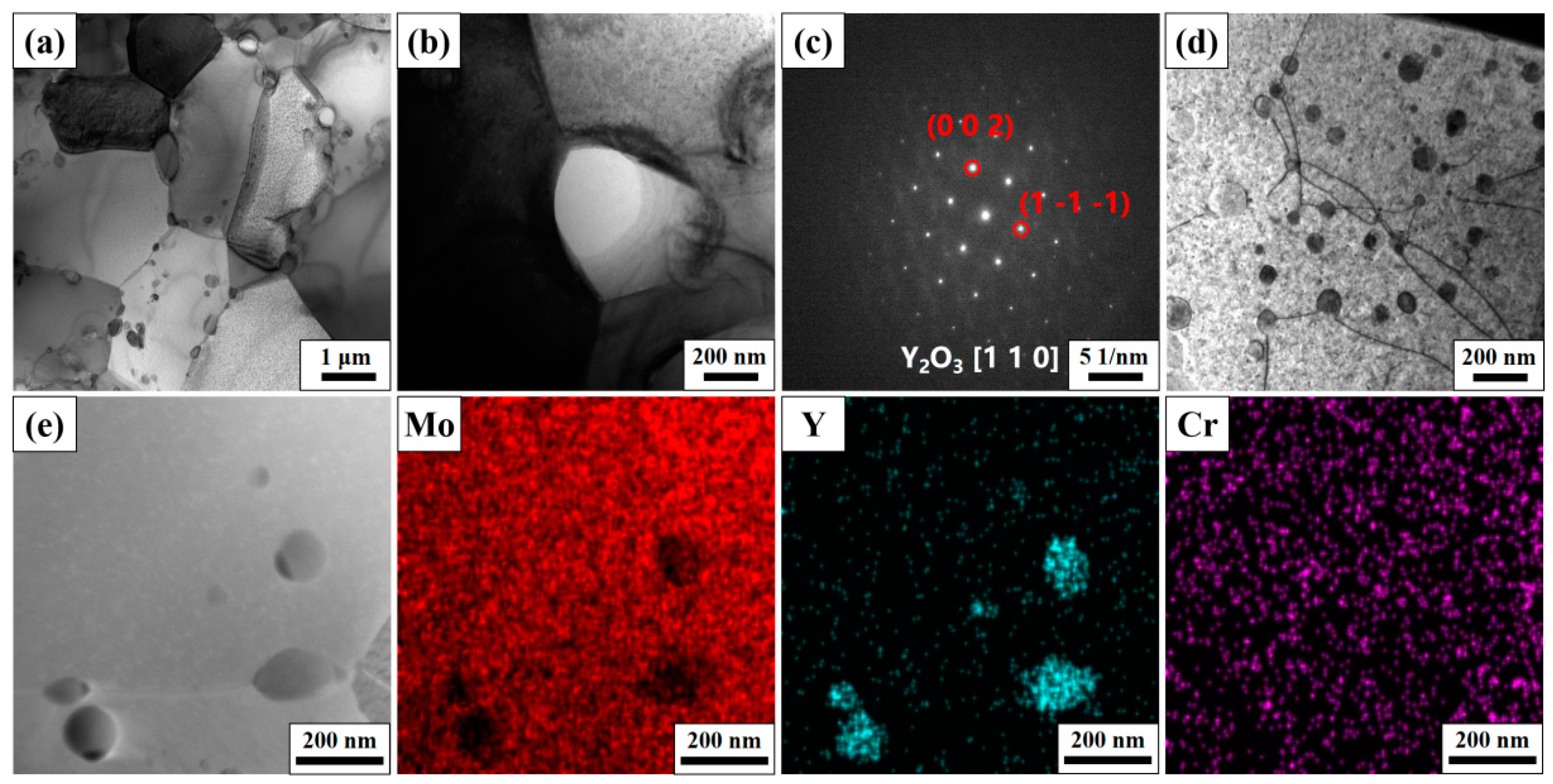

3.2. The Microstructure and Mechanical Property after Sintering

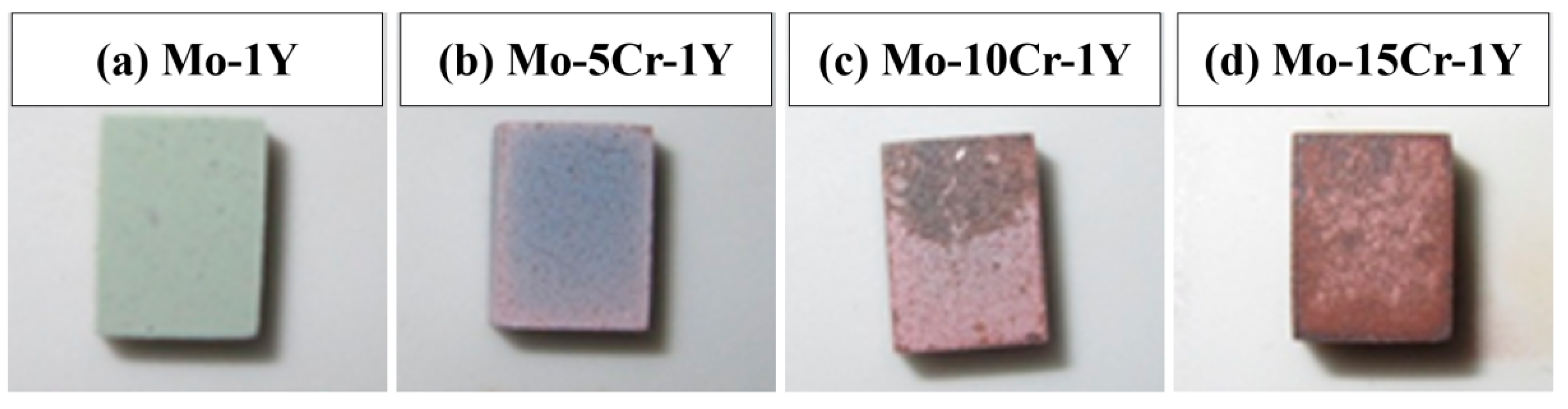

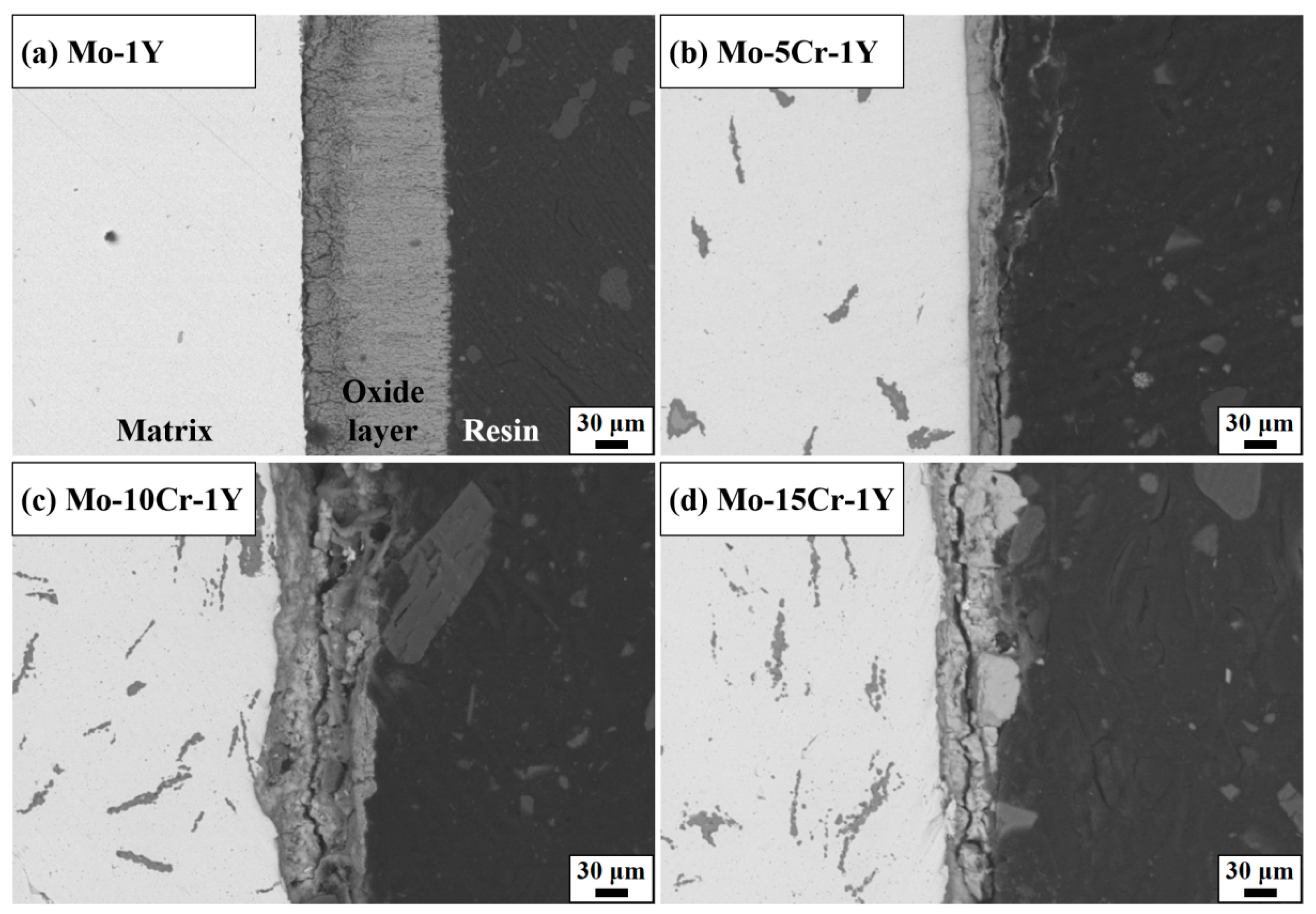

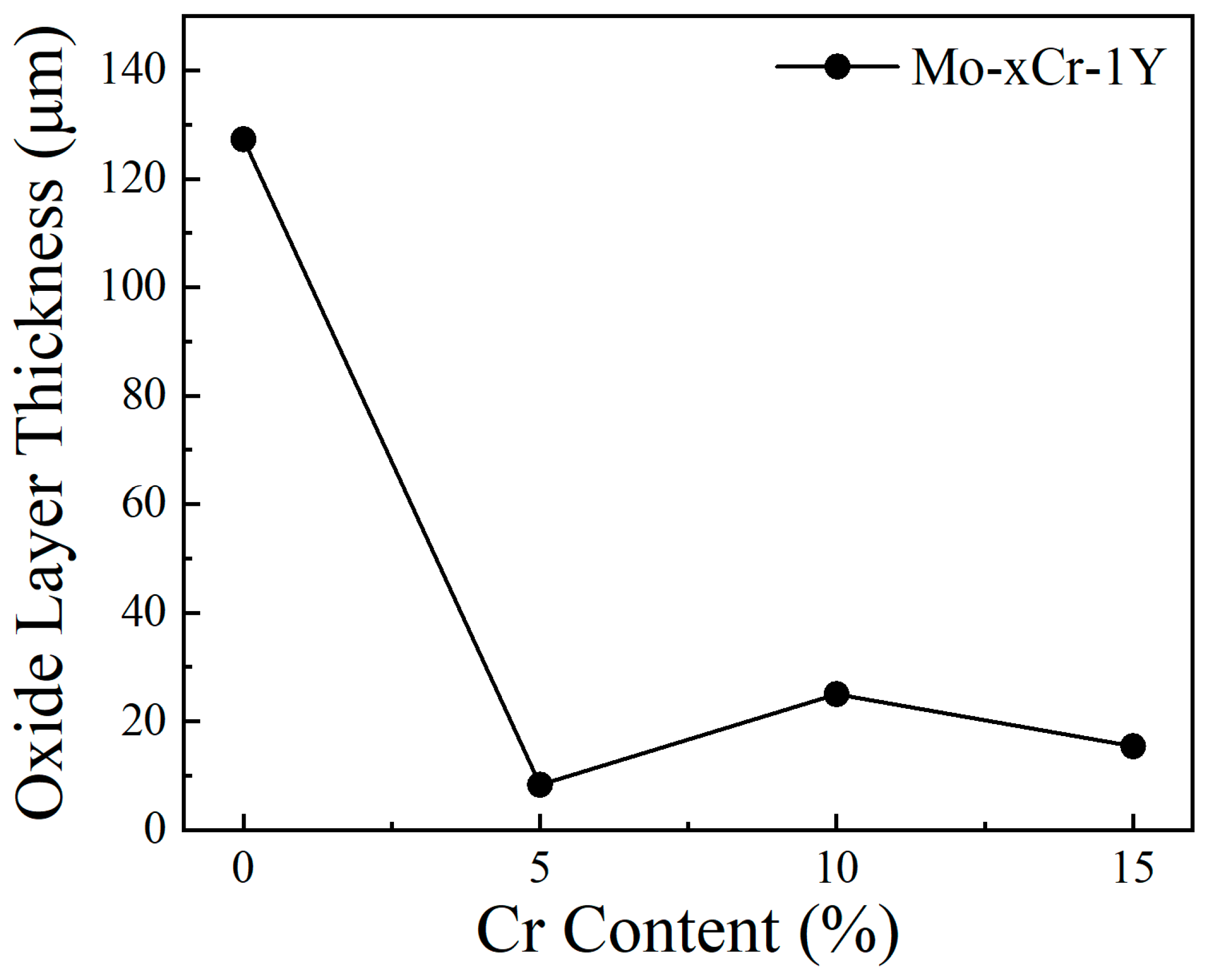

3.3. High Temperature Oxidation Behavior

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The addition of 1 wt. % Y can accelerate the densification of Mo and precipitate Y2O3 dispersion particles, thus clearly refining the grain size and strengthening the material. On this basis, adding a certain amount of Cr will further enhance the mechanical property. The Mo–1Y material with the addition of 5 wt. % Cr gave the highest bending strength of 932 MPa. However, when the addition of Cr content was higher than 10%, the bending strength was decreased, likely due to the formation of Cr-rich phases that weaken the Mo matrix, promoting crack initiation and growth;

- (2)

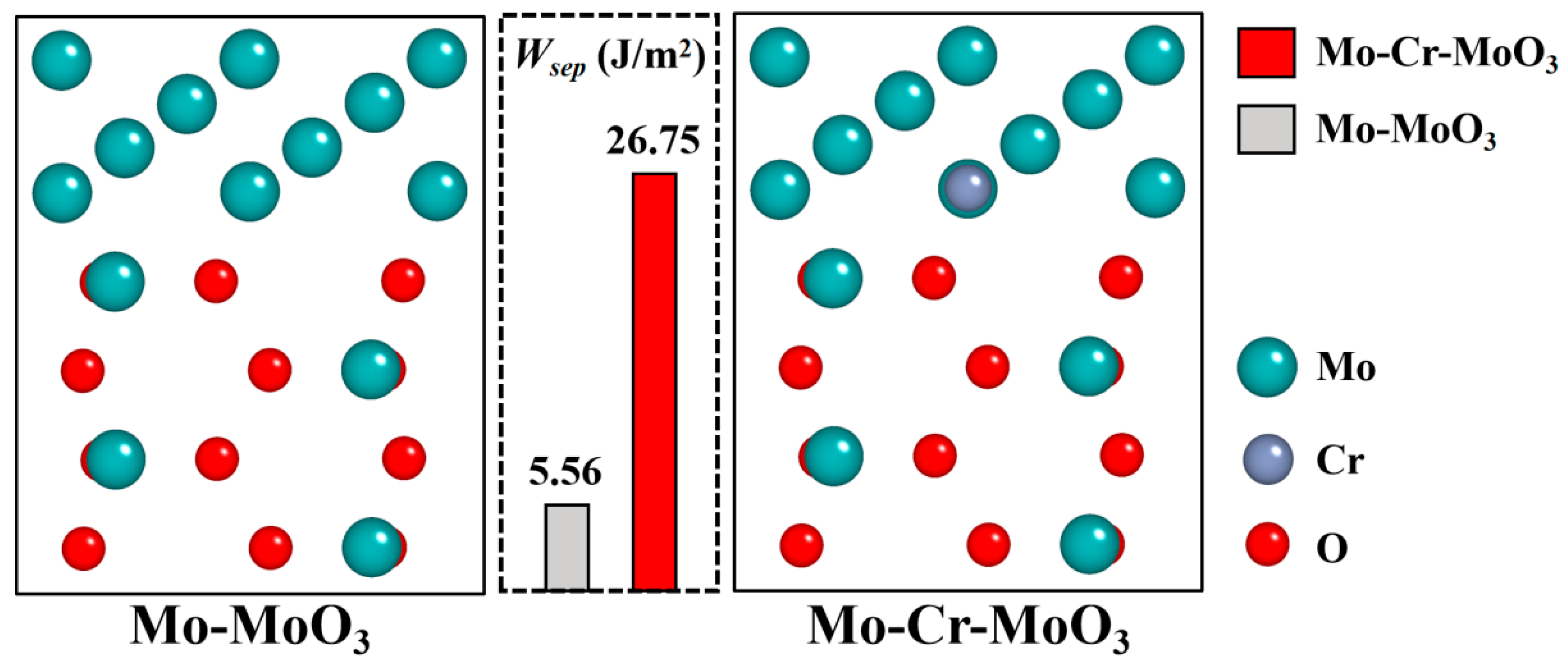

- High-temperature oxidation experiments at 600 °C demonstrated that Cr addition markedly improved the oxidation resistance of the prepared Mo alloys compared with traditional Mo alloys. The optimal performance was observed in the Mo–5Cr–1Y composite, which exhibited a significantly reduced oxide layer thickness and smooth interface between the Mo matrix and the oxide layer, as compared to the Cr-free composite. Cr not only improved the Mo-MoO3 interface bonding, but also facilitated the formation of a dense Cr2(MoO4)3 layer on the surface, which can inhibit further oxidation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, L.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, L.; Luo, K. Fabrication and reduction process of dispersive Er2O3 doped Mo super-fine powders comparing with La2O3 doped Mo powders. Powder Technol. 2019, 346, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockeram, B. The fracture toughness and toughening mechanism of commercially available unalloyed molybdenum and oxide dispersion strengthened molybdenum with an equiaxed, large grain structure. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 2843–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Naunheim, Y.; Schuh, C.; Li, Y. Breakdown of the Hall-Petch relationship in extremely fine nanograined body-centered cubic Mo alloys. Acta Mater. 2021, 213, 116950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Ren, S.; Zhang, G. Strengthening mechanisms of Mo-La2O3 alloys processed by solid-solid doping and vacuum hot-pressing sintering. Vacuum 2018, 152, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Gao, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X. Microstructure and high temperature deformation behavior of the Mo-ZrO2 alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 716, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Sun, T.; Liu, C.; Yu, L.; Ahamad, T.; Ma, Z. Refined microstructure and enhanced mechanical properties in Mo-Y2O3 alloys prepared by freeze-drying method and subsequent low temperature sintering. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 88, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, N.; Gornostyrev, Y.; Freeman, A. Solid solution softening and hardening in the group-V and group-VI bcc transition metals alloys: First principles calculations and atomistic modeling. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 212104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkle, D.; Woodward, C. The chemistry of deformation: How solutes soften pure metals. Science 2005, 310, 1665–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Deformation twinning in body-centered cubic metals and alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 139, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosse, J.; Fillit, R.; Biscondi, M. Intrinsic intergranular brittleness of molybdenum. Scr. Metall. 1981, 15, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurekawa, S.; Tanaka, T.; Yoshinaga, H. Grain boundary structure, energy and strength in molybdenum. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1994, 176, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, K.; Felfer, P.; Holec, D.; Cairney, J.; Knabl, W.; Lorich, A.; Clemens, H.; Primig, S. On grain boundary segregation in molybdenum materials. Mater. Des. 2017, 135, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, K.; Lutz, D.; Knabl, W.; Eidenberger-Schober, M.; Huber, K.; Lorich, A.; Clemens, H.; Maier-Kiener, V. Grain boundary segregation engineering in as-sintered molybdenum for improved ductility. Scr. Mater. 2018, 156, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Kenik, E.; Mousa, M.; Russell, K.; Bryhan, A. Improvement in the ductility of molybdenum alloys due to grain boundary segregation. Scr. Mater. 2002, 46, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Bryhan, A. Effect of Zr, B and C additions on the ductility of molybdenum. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 327, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, K.; Liu, R.; Xie, Z.; Ke, J.; Wang, X.; Fang, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Wu, X. Excellent high-temperature strength and ductility of the ZrC nanoparticles dispersed molybdenum. Acta Mater. 2022, 227, 117725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Coupling effect of intergranular and intragranular particles on ductile fracture of Mo–La2O3 alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 640, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Gong, F.; Liu, S.; Tan, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, Z. Microstructure refinement and second phase particle regulation of Mo−Y2O3 alloys by minor TiC additive. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 2012–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Raveendra, S.; Samajdar, I.; Bhargava, P.; Sharma, I. Densification and grain growth during isothermal sintering of Mo and mechanically alloyed Mo–TZM. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 4158–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scattergood, R.; Bacon, D. The Orowan mechanism in anisotropic crystals. Philos. Mag. 1975, 31, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y.L.; Wang, M.P.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.X. The microstructure and texture of Mo–La2O3 alloys with high transverse ductility. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 589, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, G.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Sun, J. Microstructure and strengthening mechanisms of molybdenum alloy wires doped with lanthanum oxide particles. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2009, 27, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y. Phase interface engineering: A new route towards ultrastrong yet ductile Mo alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 889, 145867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, N.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Duan, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. Effects of shape and size of second phase on mechanical properties of sintered Mo-Y2O3 alloys. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, N.; Song, W.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, S.; Shen, H. Achieving an unprecedented strength-ductility balance of molybdenum alloy by homogeneously distributing yttrium-cerium oxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 897, 163110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, F.; Ding, X.; Sun, Y.; Sun, J.; Ma, E. Nanostructured high-strength molybdenum alloys with unprecedented tensile ductility. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulbransen, E.; Andrew, K.; Brassart, F. Oxidation of Molybdenum 550°C to 1700°C. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1963, 110, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Gorr, B.; Christ, H.; Schliephake, D.; Heilmaier, M. Oxidation mechanisms of lanthanum-alloyed Mo–Si–B. Corros. Sci. 2014, 88, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Chou, K. Study on oxidation mechanism and kinetics of MoO2 to MoO3 in air atmosphere. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2016, 57, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Miura, S.; Ikeda, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y. The oxidation mechanism of nanostructured Y-Zr-O complex oxide dispersion-strengthened Mo alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 968, 172204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badini, C.; Laurella, F. Oxidation of FeCrAl alloy: Influence of temperature and atmosphere on scale growth rate and mechanism. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 135, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, K.; Huang, W.; Lu, Z. Mechanisms of Al2O3 and Cr2O3 formation during FeCrAl alloy Oxidation: A First-Principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 644, 158782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, X. Research progress of ODS FeCrAl alloys–a review of composition design. Materials 2023, 16, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götlind, H.; Liu, F.; Svensson, J.; Halvarsson, M.; Johansson, L.-G. The effect of water vapor on the initial stages of oxidation of the FeCrAl alloy Kanthal AF at 900°C. Oxid. Met. 2007, 67, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkina, K.; Hallatt, D.; Geiger, E.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Sakamoto, K.; Shibata, H.; Piro, M. A study of the oxidation behaviour of FeCrAl-ODS in air and steam environments up to 1400°C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 541, 152305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, Q.; Zhong, M.; Arshad, K. Effect of rare earth elements on the consolidation behavior and microstructure of tungsten alloys. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 48, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, Z.; Tan, J.; Ding, Q.; Zhong, M. Effects of ball milling parameters on microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of W-3% Y composites. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 465, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.; Wang, J. Embrittlement of interfaces by solute segregation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1989, 107, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabero, P. Synthesis of Cr2(MoO4)3. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 1999, 67, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Mo | Y | Cr |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo | 100 | - | - |

| Mo-1Y | 99 | 1 | - |

| Mo–5Cr–1Y | 1 | 5 | |

| Mo–10Cr–1Y | 1 | 10 | |

| Mo–15Cr–1Y | 1 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, H.; Lv, C.; Ding, Q.; Wang, G.; Xiong, N.; Zhou, Z. The Effect of Cr Addition on the Strength and High Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Mo Composites. Materials 2024, 17, 2550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112550

Guan H, Lv C, Ding Q, Wang G, Xiong N, Zhou Z. The Effect of Cr Addition on the Strength and High Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Mo Composites. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112550

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Haochen, Chongshan Lv, Qingming Ding, Guangda Wang, Ning Xiong, and Zhangjian Zhou. 2024. "The Effect of Cr Addition on the Strength and High Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Mo Composites" Materials 17, no. 11: 2550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112550

APA StyleGuan, H., Lv, C., Ding, Q., Wang, G., Xiong, N., & Zhou, Z. (2024). The Effect of Cr Addition on the Strength and High Temperature Oxidation Resistance of Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Mo Composites. Materials, 17(11), 2550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112550