Utilizing Industrial Sludge Ash in Brick Manufacturing and Quality Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization and Conditioning of Raw Materials

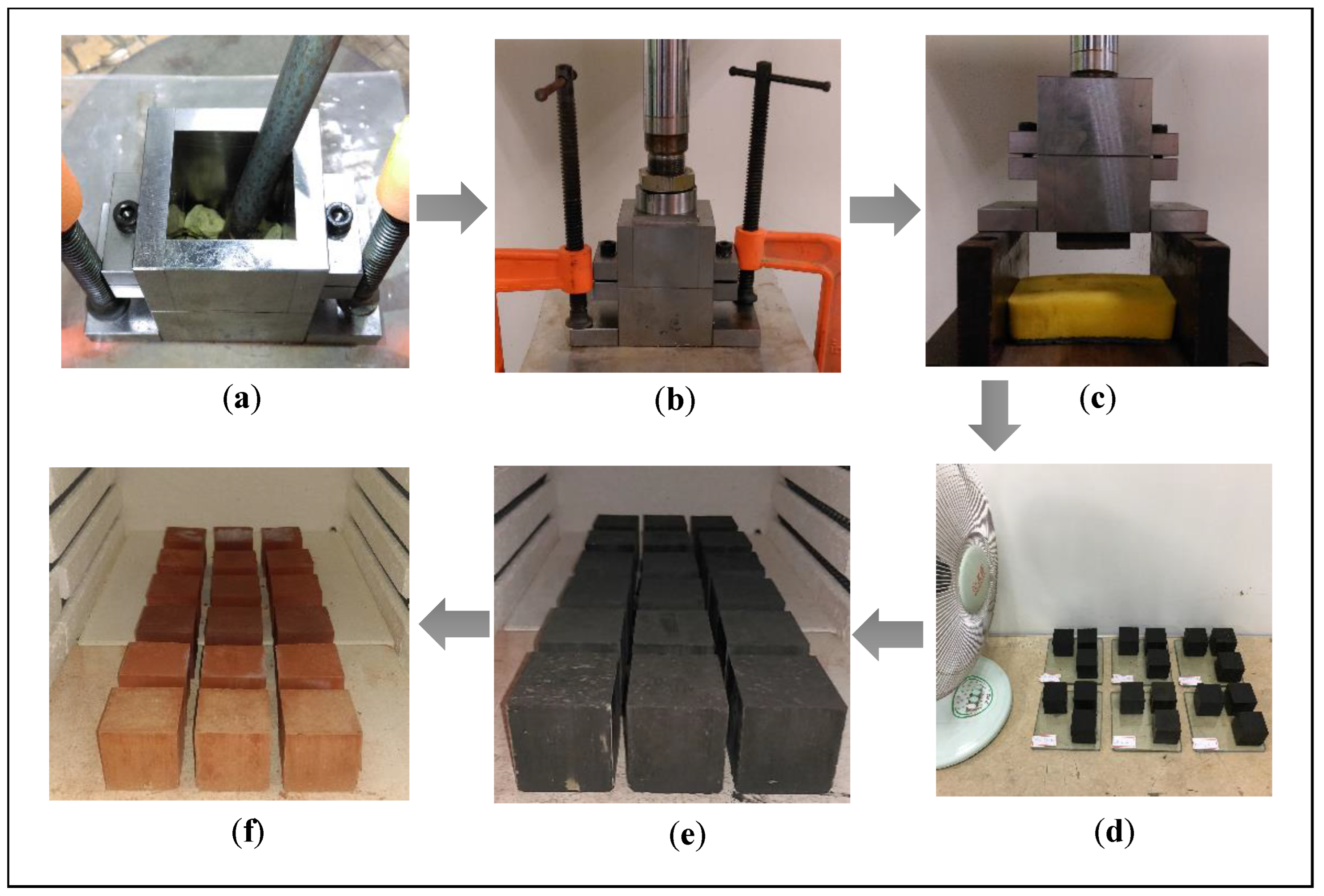

2.2. Preparation of Bricks

2.3. Testing Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

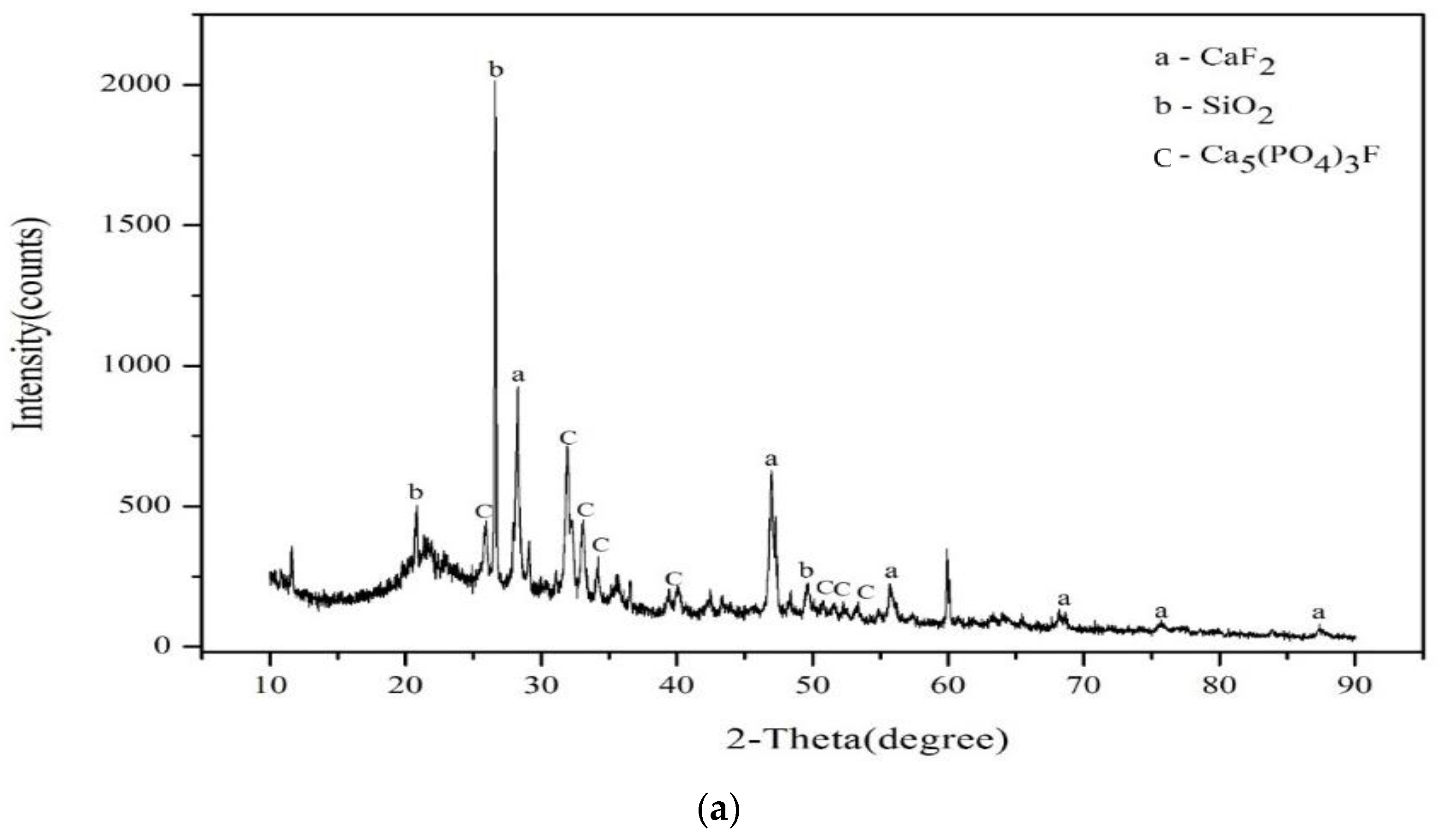

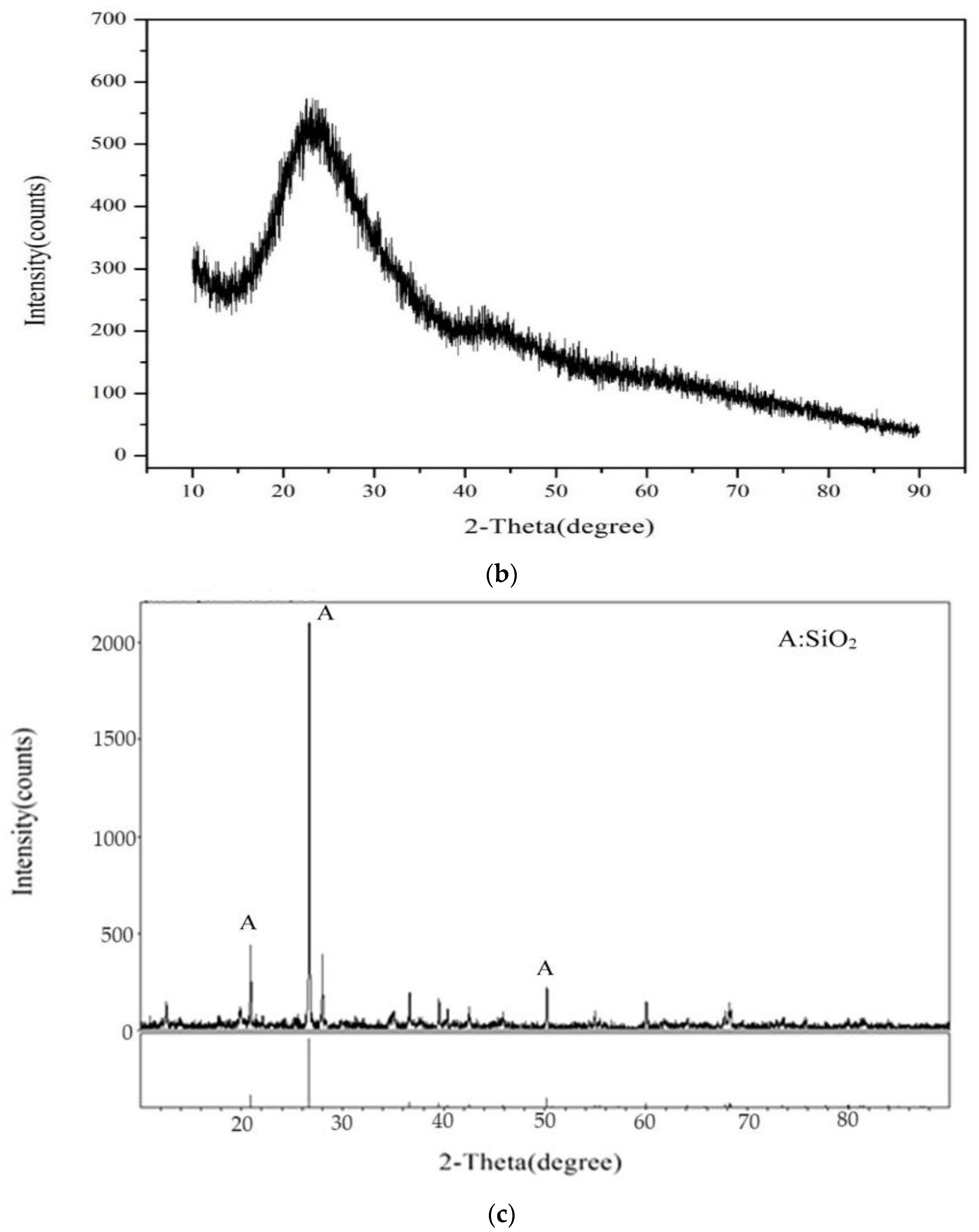

3.1. Characterization of Raw Materials Used for Brick Manufacturing

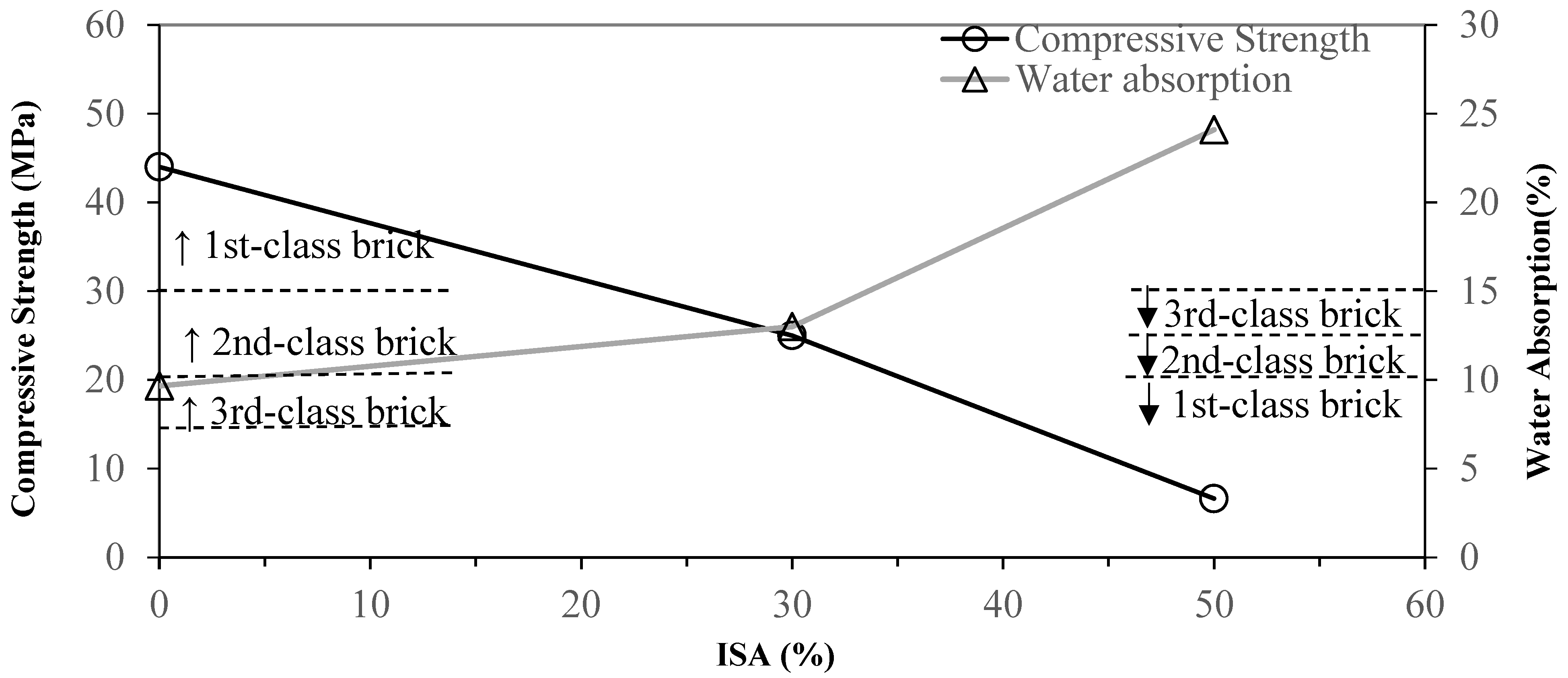

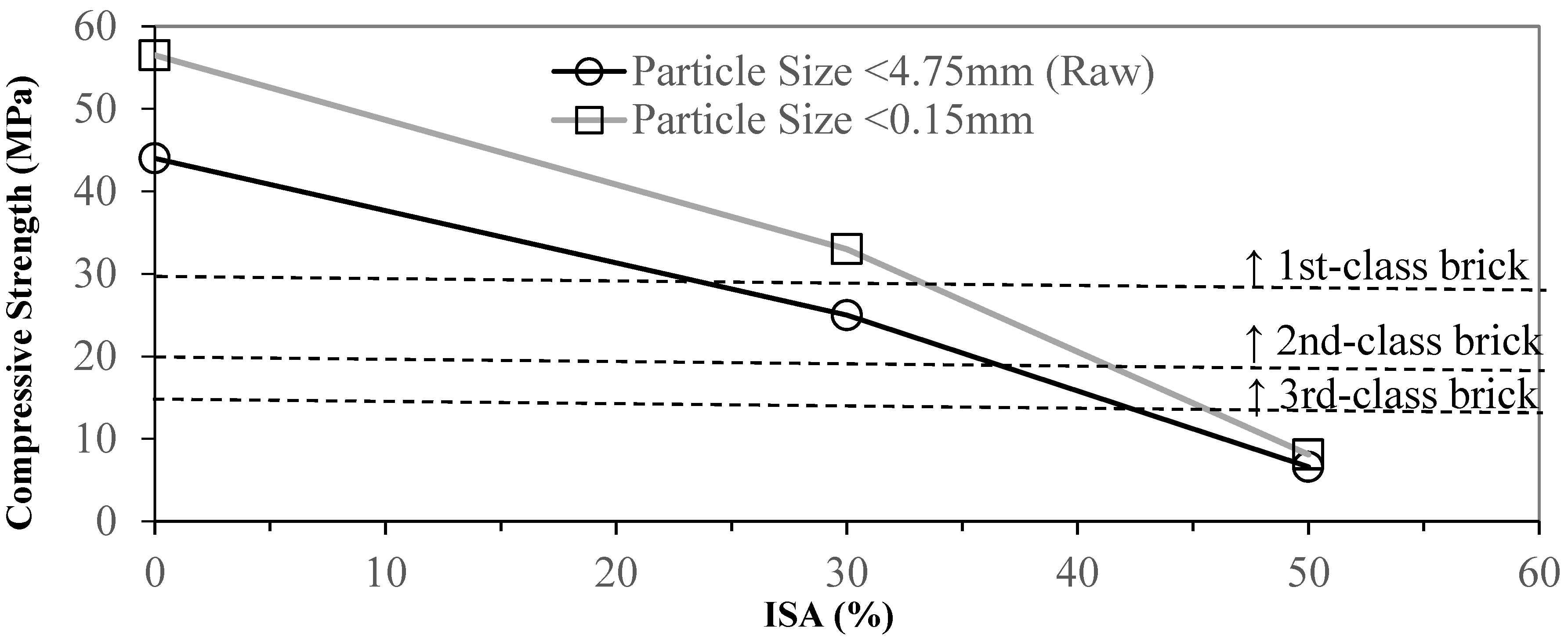

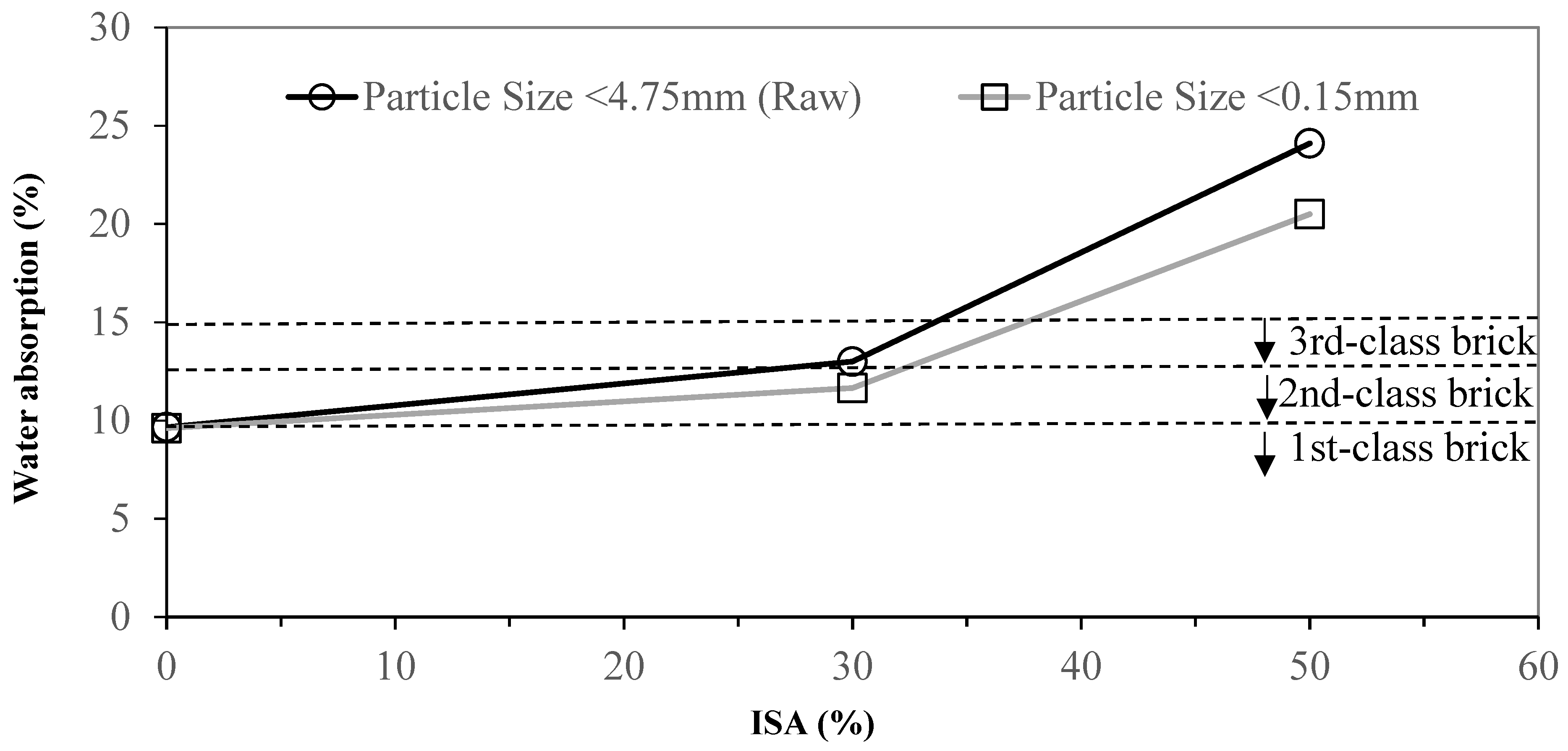

3.2. Effects of Industrial Sludge Ash Content on Brick

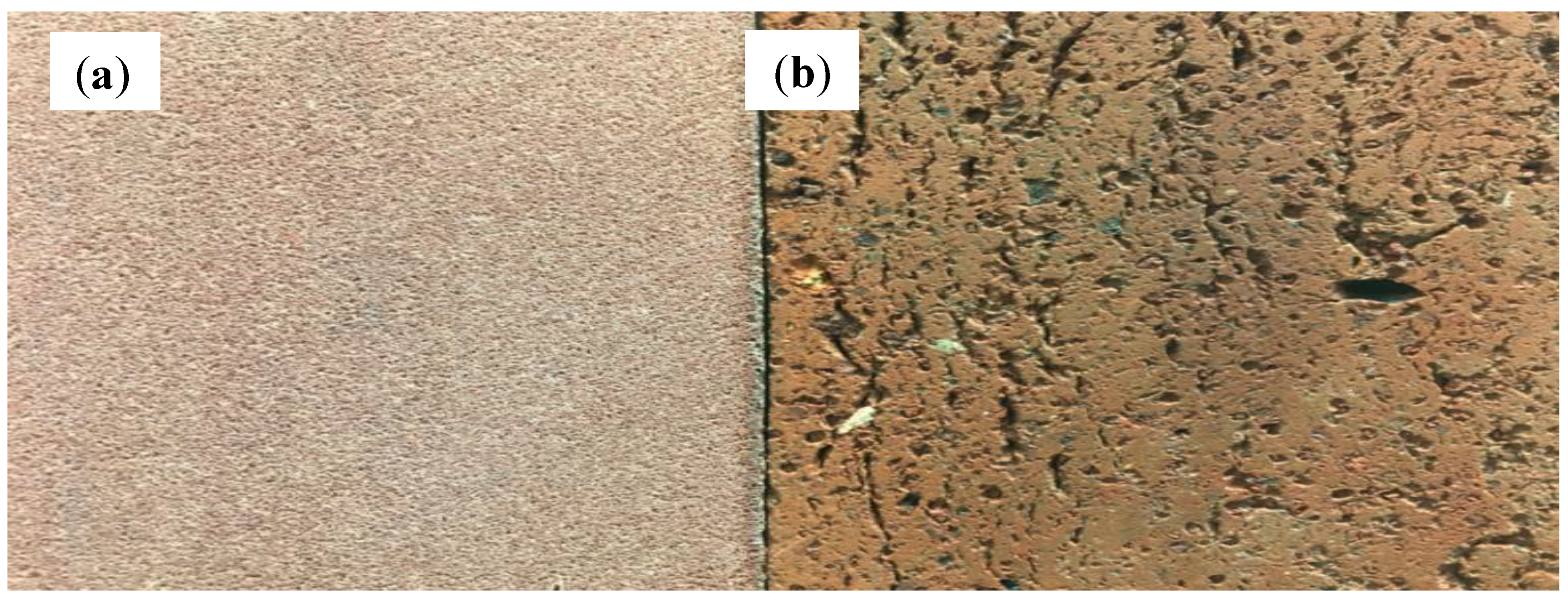

3.3. Process Improvement

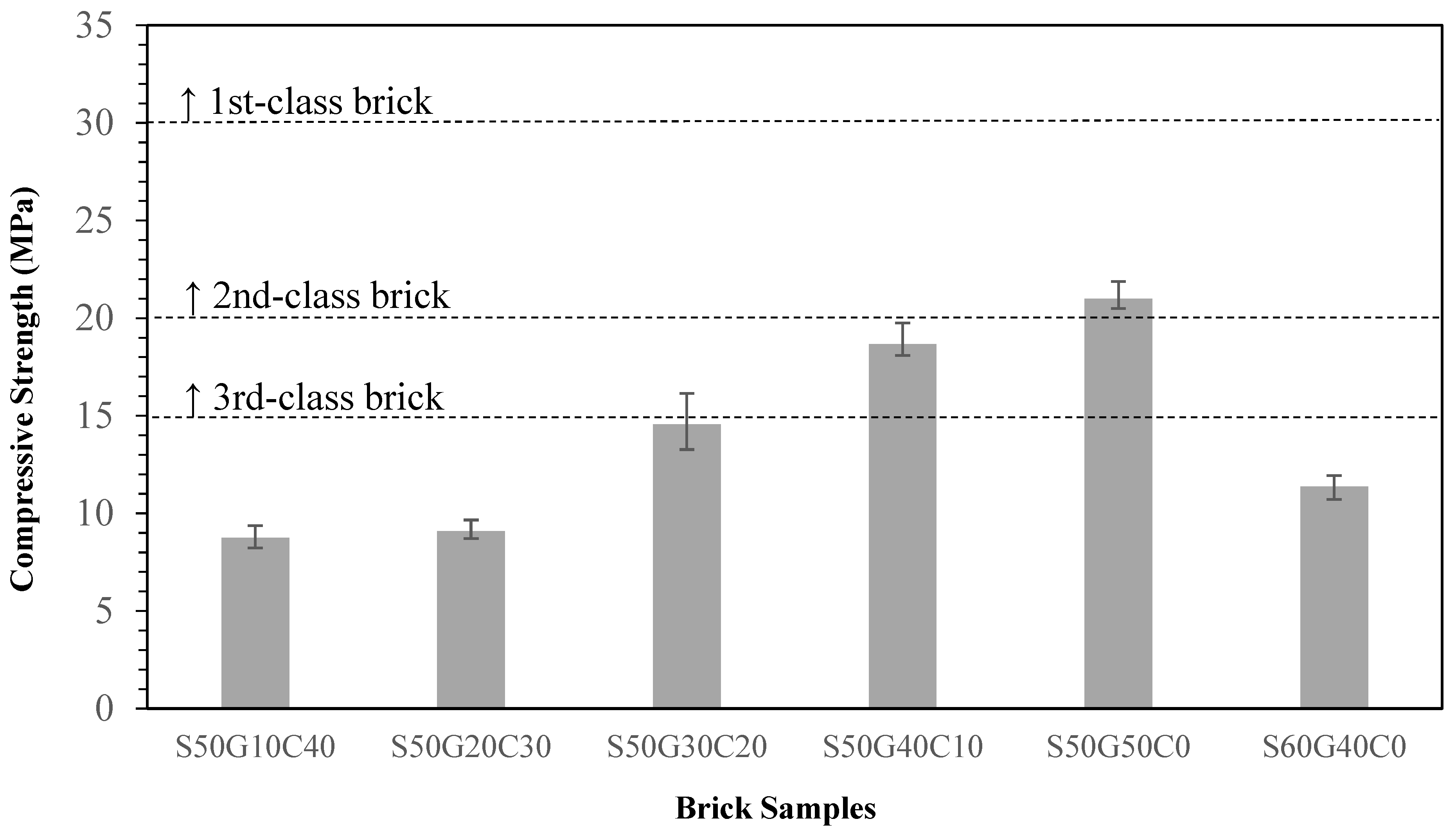

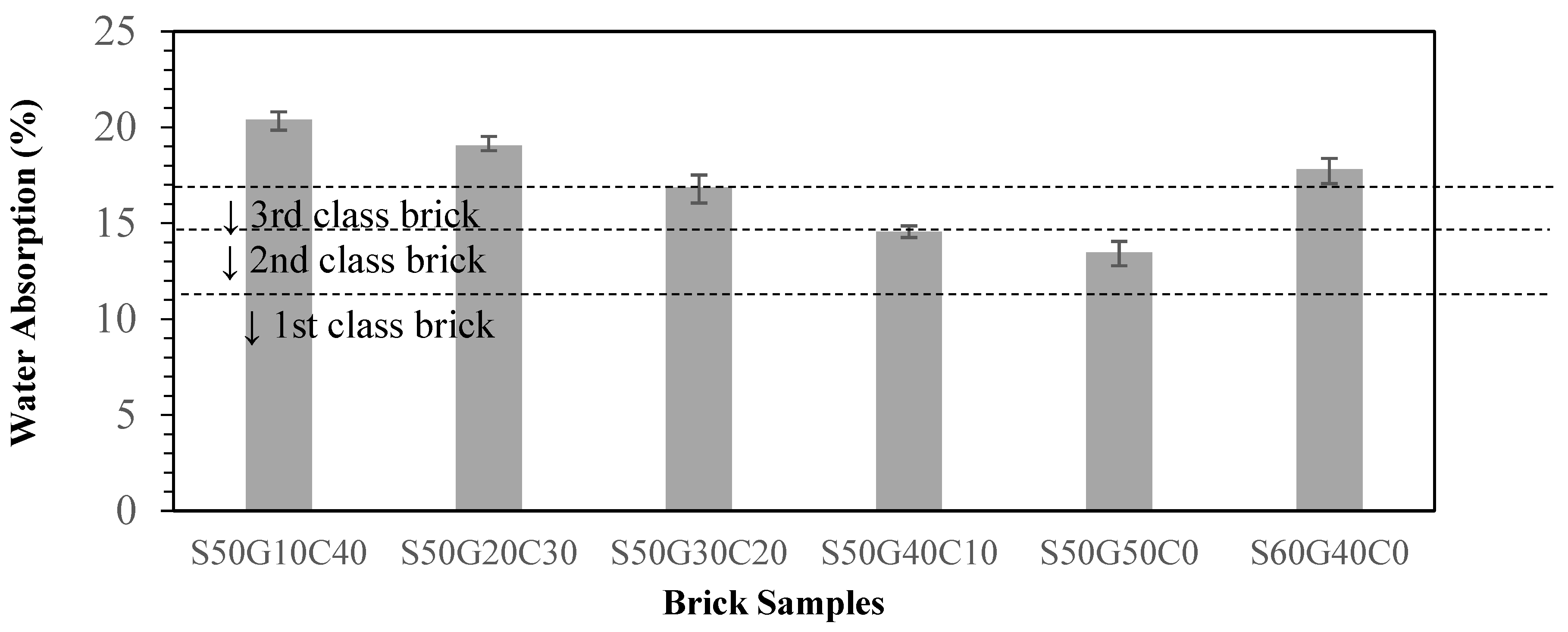

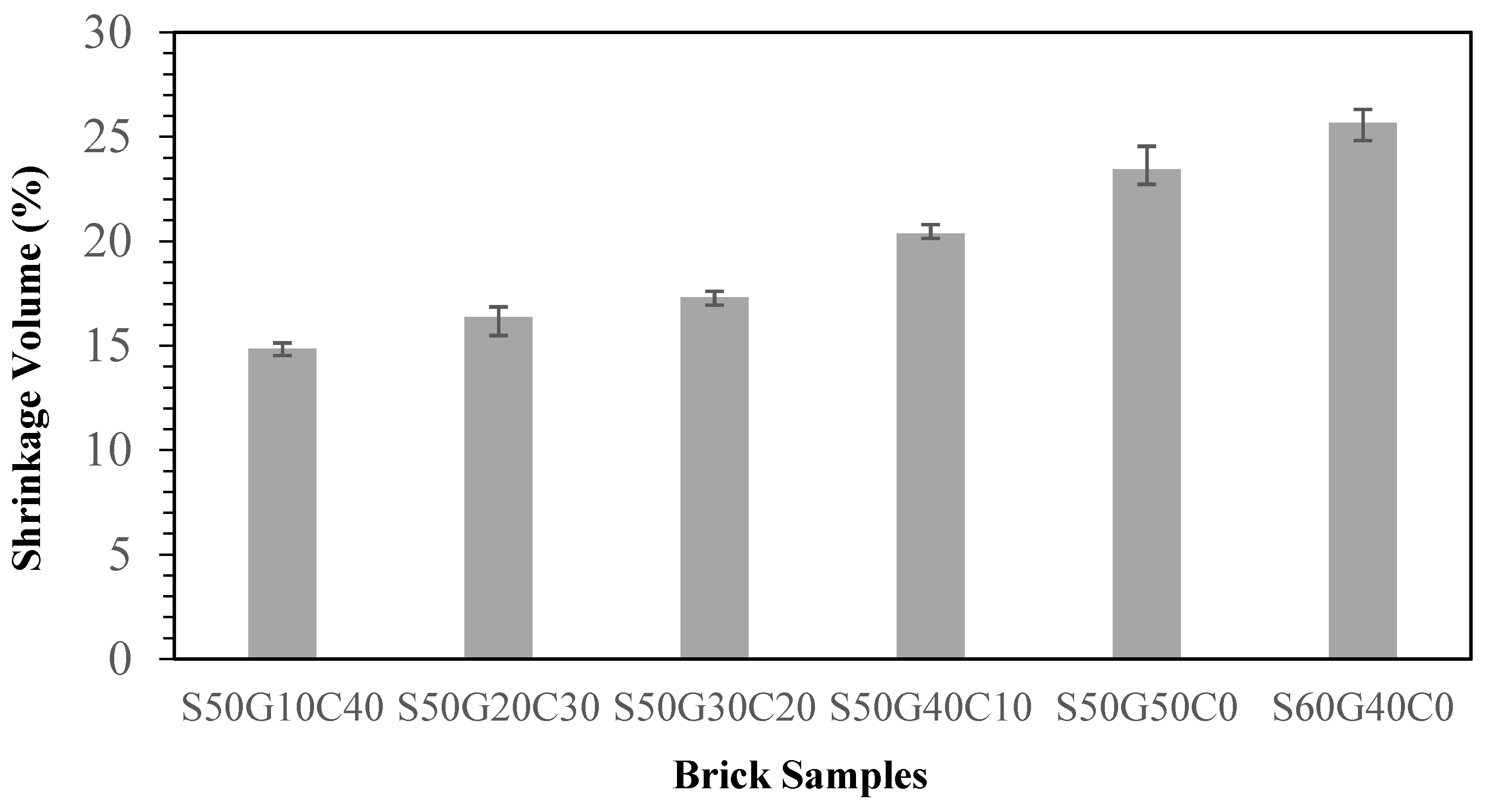

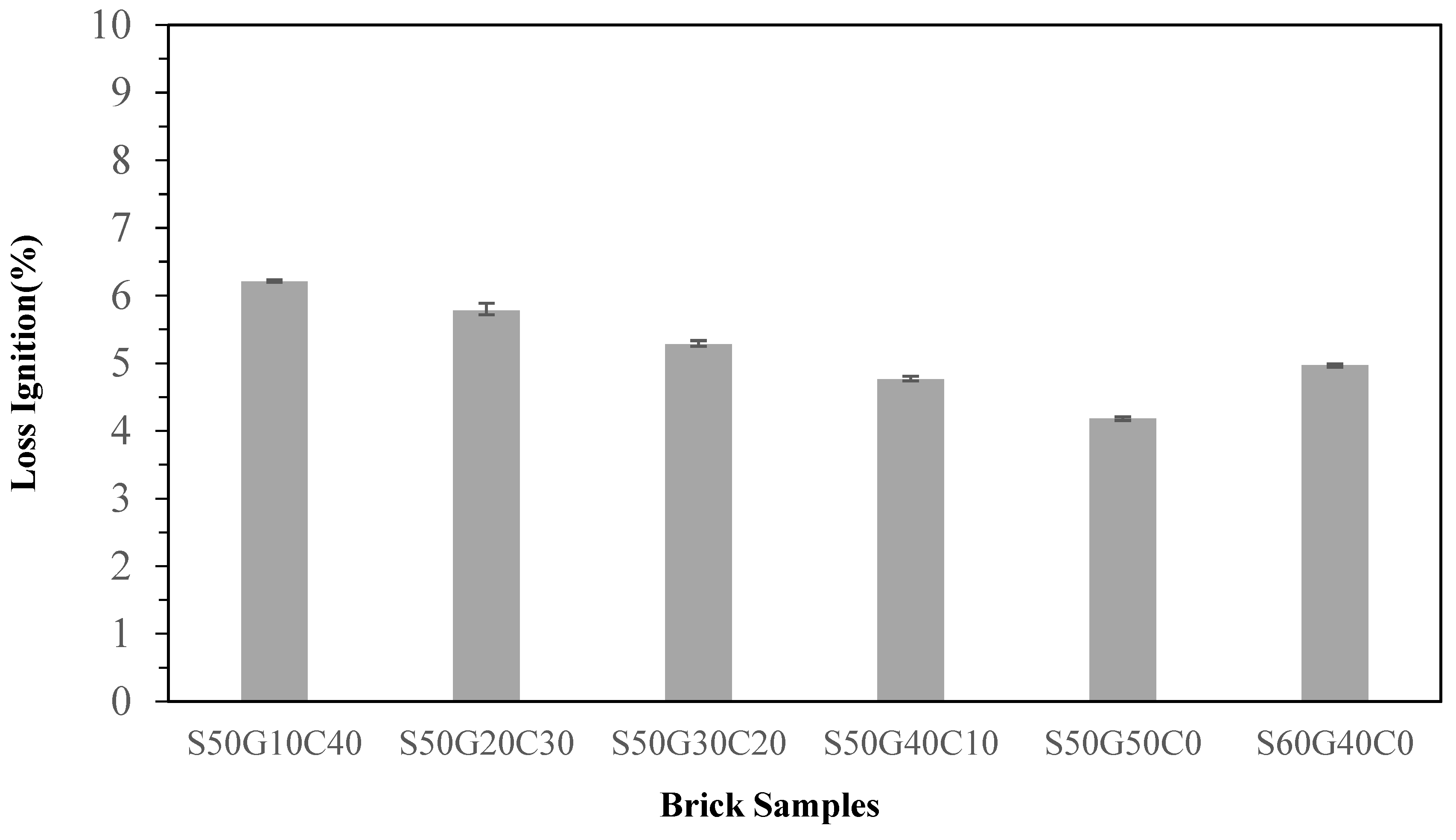

3.4. Effects of Fluxing Agents on Properties of Brick

4. Conclusions

- Grinding and sieving (<0.15 mm) the materials reduce the particle sizes and homogenize the materials, which increases the reacting area. This enhances the quality of the bricks. Compared to the pure clay standard, adding 30% of ground and sieved ISA increases the compressive strength by 31.6% and decreases the water absorption ratio by 11.8%

- Adding WG increases the overall quality of the brick and the substitution potential. Adding 40~50% of WG meets the third-class brick standard.

- Replacing 50% of clay with ISA while the other 50% of clay is replaced with glass is the best solution, with excellent waste utilization and the best compressive strength and water absorption ratio. However, considering the actual manufacturing process and the strength requirement, an ISA50%/WG40%/Clay10% ratio is recommended.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williford, C.; Chen, W.Y.; Shamas, N.K.; Wang, L.K.; Lime Stabilization. Biosolids Treatment Processes; Handbook of Environmental Engineering; Humana Press: Totowa, NI, USA, 2007; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, A.; Emmanuel, O. The Impact of Taxation on Revenue Generation in Nigeria: A Study of Federal Capital Territory and Selected States. Int. J. Public Adm. Manag. Res. (IJPAMR) 2014, 2, 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, M.H.; Khitab, A.; Ahmed, S. Evaluation of sustainable clay bricks incorporating Brick Kiln Dust. J. Eng. 2019, 24, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, Y.J.; Tseng, Y.C.; Cha, S.C.; Lo, N.W.; Chung, G.; Liu, C.K. Motivations, Deployment, and Assessment of Taiwan’s E-Invoicing System: An Overview. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 2200–2209. [Google Scholar]

- Basegio, T.; Berutti, F.; Bernardes, A.; Bergmann, C.P. Environmental and technical aspects of the utilisation of tannery sludge as a raw material for clay products. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 22, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.R.; Santos, G.T.A.; Souza, A.E.; Alessio, P.; Souza, S.A.; Souza, N.R. The effect of incorporation of a Brazilian water treatment plant sludge on the properties of ceramic materials. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 53, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, C.R.; Sollars, C.J.; McEntee, S. Properties, microstructure and leaching of sintered sewage sludge ash. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2003, 40, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.Y.; Chien, K.L.; Hwang, S.J. Study on the characteristics of building bricks produced from reservoir sediment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 159, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.P.; Shie, J.L.; Chang, C.Y.; Shih, S.M.; Lee, D.J.; Wu, C.H. Pyrolysis of oil sludge with additives of catalytic solid wastes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2004, 71, 695–707. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Mansori, M.; Hakkou, R. Recycling Feasibility of Glass Wastes and Calamine Processing Tailings in Fired Bricks Making. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, C.; Wu, Q. Use of electroplating sludge in production of fired clay bricks: Characterization and environmental risk evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, M.J.; Kazmi, S.M.S.; Gencel, O.; Ahmad, M.R.; Chen, B. Synergistic effect of rice husk, glass and marble sludges on the engineering characteristics of eco-friendly bricks. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q. The reuse of waste glass for enhancement of heavy metals immobilization during the introduction of galvanized sludge in brick manufacturing. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loryuenyong, V.; Panyachai, T.; Kaewsimork, K.; Siritai, C. Effects of recycled glass substitution on the physical and mechanical properties of clay bricks. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2717–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phonphuak, N.; Kanyakam, S.; Chindaprasirt, P. Utilization of waste glass to enhance physical–mechanical properties of fired clay brick. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112 Pt 4, 3057–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance, R.O.C. 2021. Available online: https://web02.mof.gov.tw/njswww/WebMain.aspx?sys=100&funid=defjsptgl (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection, M.O.E.A., R.O.C. Available online: https://www.cnsonline.com.tw/?locale=zh_TW (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- ASTM International. USA. Available online: https://www.astm.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- ASTM C67-14; Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Brick and Structural Clay Tile. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Skrifvars, B.J.; Hupa, M.; Backman, R.; Hiltunen, M. Sintering mechanisms of FBC ashes. Fuel 1994, 73, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.Y.; Yeh, M.; Glass, J. Hepcidin regulation of ferroportin 1 expression in the liver and intestine of the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 2004, 286, G385–G394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Du, B.; Wang, N. Preparation and strength property of autoclaved bricks from electrolytic manganese residue. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Park, W.W.; Choi, B.H.; You, B.S.; Huang, Y.B.; Park, I.M. Effect of Ca addition on the oxidation resistance of AZ91 magnesium alloys at elevated temperatures. Met. Mater. Int. 2003, 9, 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, J. Slag from hazardous waste incineration: Reduction of heavy metal leaching. Waste Manag. Res. 2003, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Brick Samples | ISA (%) | WG (%) | Clay (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | ||||||

| <4.75 mm (Raw) | <0.15 mm | <4.75 mm (Raw) | <0.15 mm | <4.75 mm (Raw) | <0.15 mm | |

| C100 | - | - | - | - | 100 | - |

| RS30RC70 | 30 | - | - | - | 70 | - |

| RS50RC50 | 50 | - | - | - | 50 | - |

| S30C70 | - | 30 | - | - | - | 70 |

| S50C50 | - | 50 | - | - | - | 50 |

| S50G10C40 | - | 50 | - | 10 | - | 40 |

| S50G20C30 | - | 50 | - | 20 | - | 30 |

| S50G30C20 | - | 50 | - | 30 | - | 20 |

| S50G40C10 | - | 50 | - | 40 | - | 10 |

| S50G50C0 | - | 50 | - | 50 | - | - |

| S60G40C0 | - | 60 | - | 60 | - | - |

| Properties | ISA | WG | Clay |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 (%) | 41.80 | 63.91 | 60.72 |

| Al2O3 (%) | 8.69 | 16.44 | 20.55 |

| Fe2O3 (%) | 7.67 | 0.29 | 9.62 |

| CaO (%) | 31.31 | 9.57 | 0.84 |

| P2O5 (%) | 13.58 | - | - |

| SO3 (%) | 3.58 | - | - |

| ZnO (%) | 0.37 | 0.23 | - |

| Cr2O3 (%) | 0.15 | - | - |

| NiO (%) | 0.13 | - | - |

| K2O (%) | 0.97 | - | 5.29 |

| MnO2 (%) | - | - | 0.16 |

| CuO (%) | 0.38 | - | - |

| TiO2 (%) | 0.34 | 0.17 | 1.34 |

| Specific gravity | 2.28 | 2.51 | 2.47 |

| Water content (%) | 1.64 | - | 1.89 |

| Absorption (%) | 23.54 | - | 11.35 |

| Combustibility (%) | 3.24 | - | 5.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.-M.; Chen, C.-S.; Chen, C.-C.; Lai, J.-W. Utilizing Industrial Sludge Ash in Brick Manufacturing and Quality Improvement. Materials 2024, 17, 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112568

Huang Y-M, Chen C-S, Chen C-C, Lai J-W. Utilizing Industrial Sludge Ash in Brick Manufacturing and Quality Improvement. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112568

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yu-Ming, Chao-Shi Chen, Chen-Chung Chen, and Jian-Wen Lai. 2024. "Utilizing Industrial Sludge Ash in Brick Manufacturing and Quality Improvement" Materials 17, no. 11: 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112568

APA StyleHuang, Y.-M., Chen, C.-S., Chen, C.-C., & Lai, J.-W. (2024). Utilizing Industrial Sludge Ash in Brick Manufacturing and Quality Improvement. Materials, 17(11), 2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112568