The Influence of Selected Process Parameters on the Efficiency of the Process of Gas Nitriding of AISI 1085 Steel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

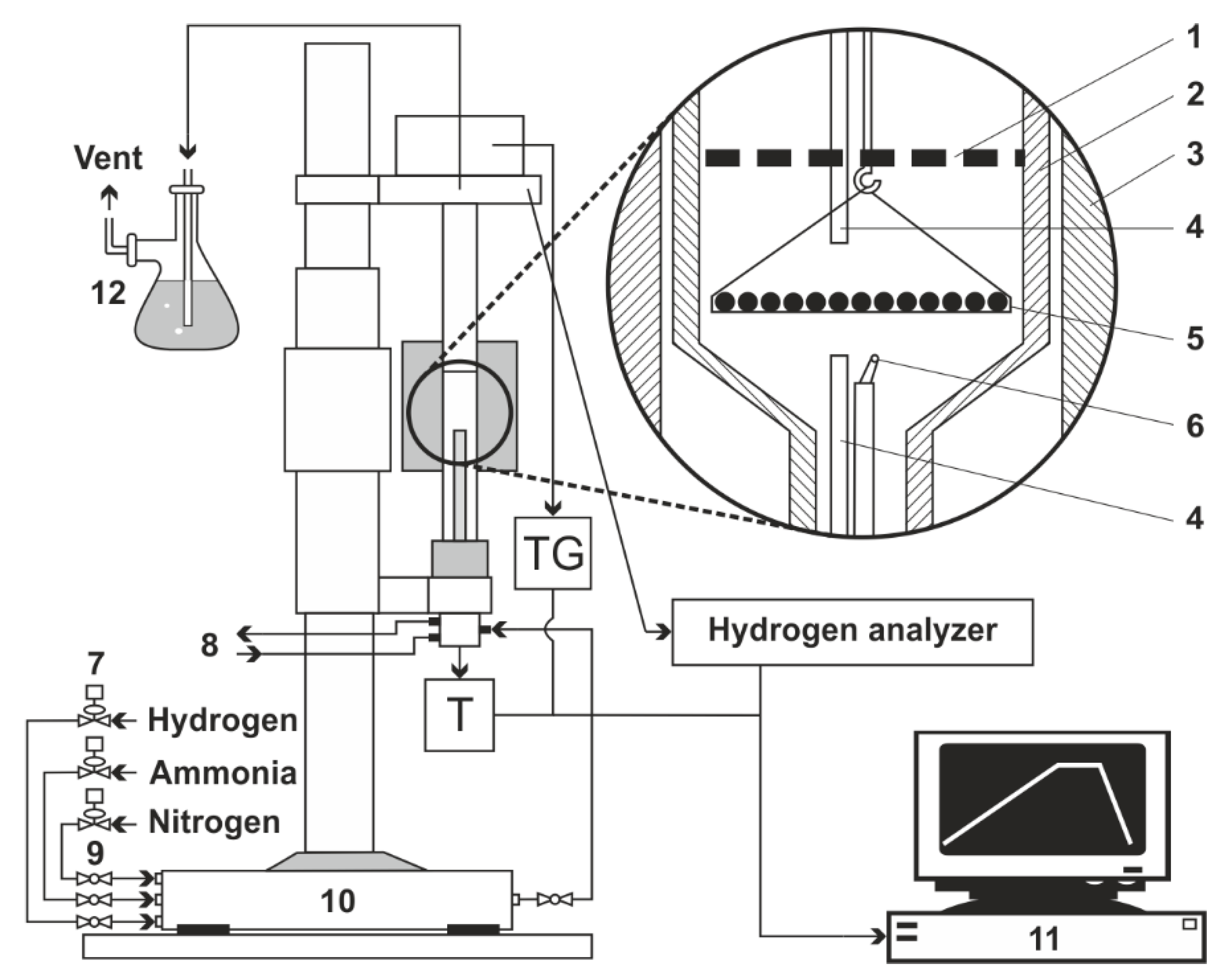

2. Research and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

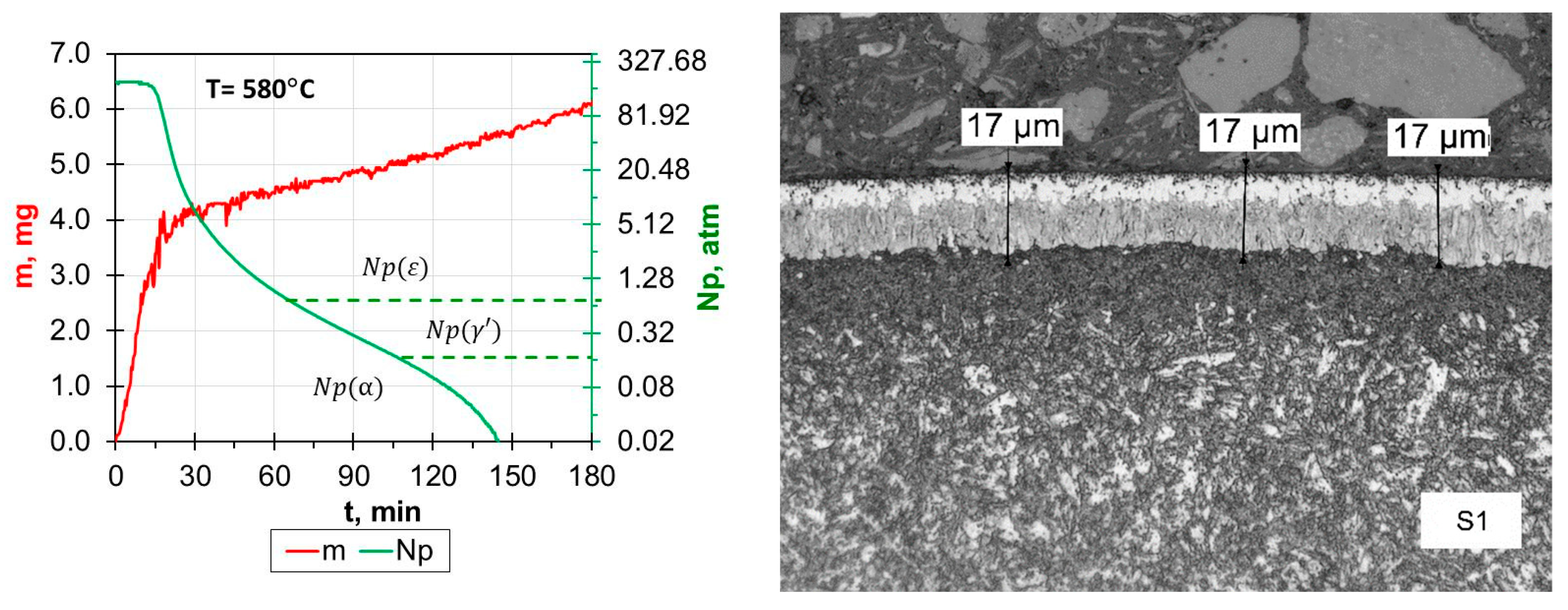

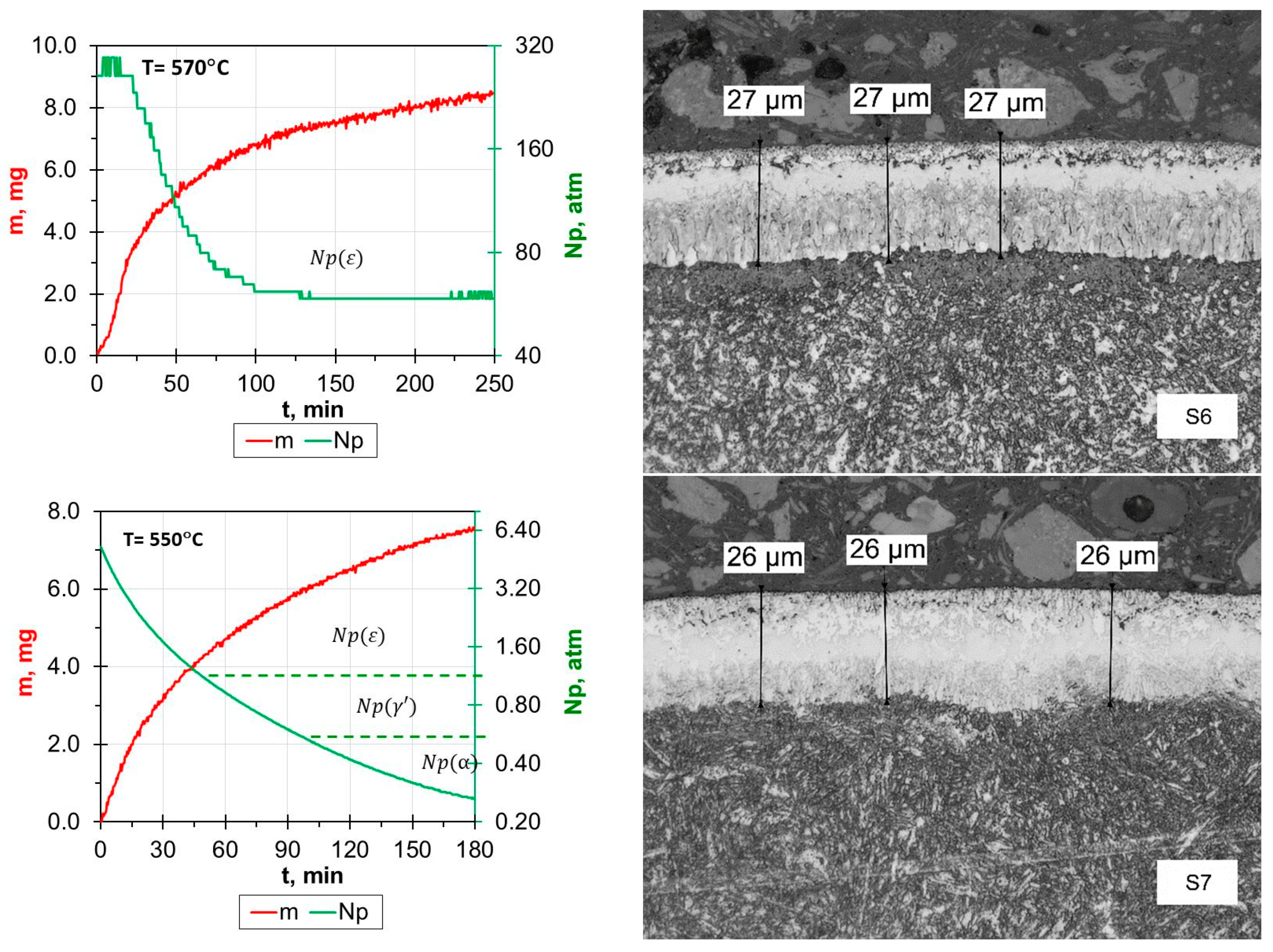

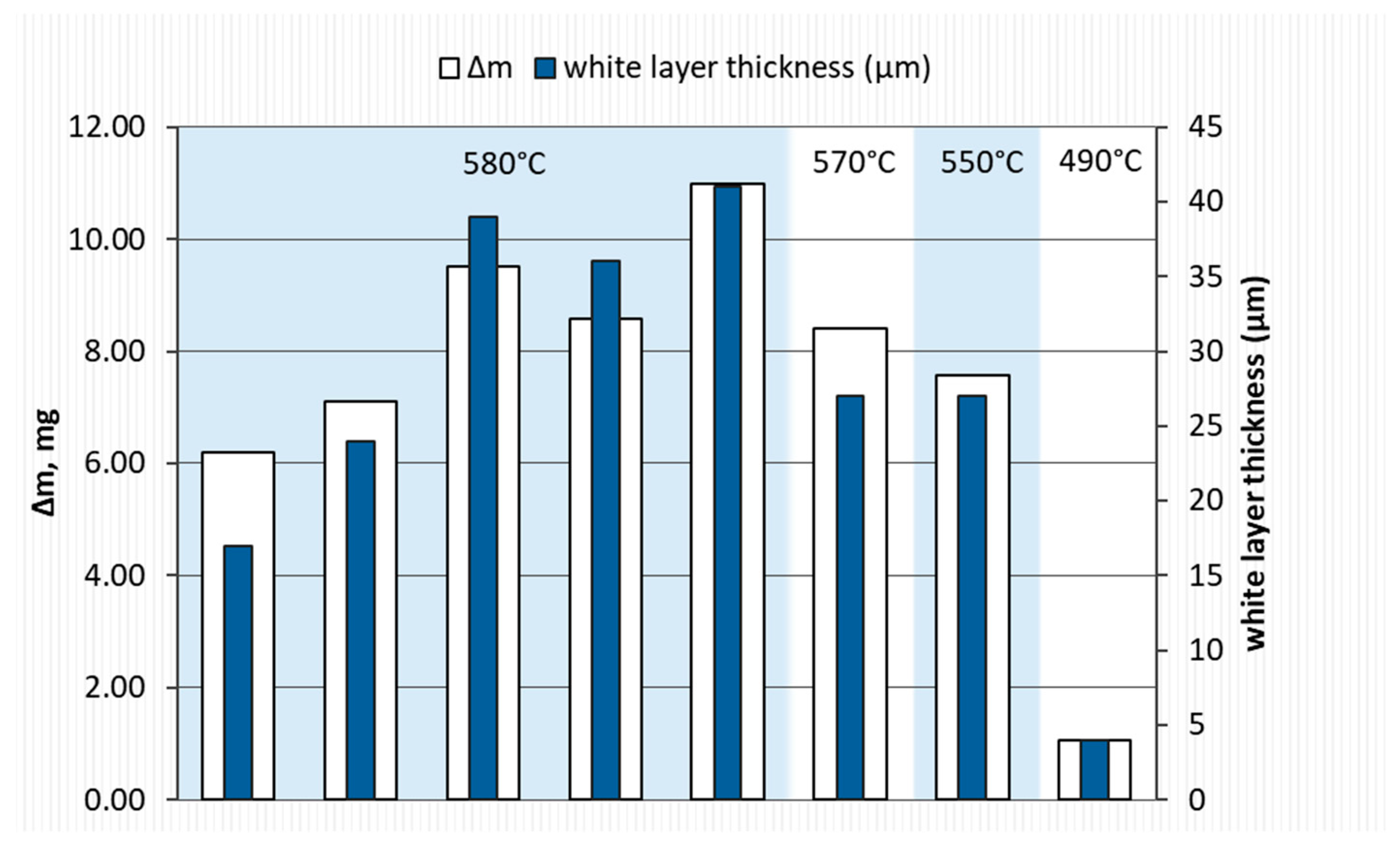

- Reducing the amount of NH3 by adding H2 or N2 resulted in obtaining nitrided layers of a lower thickness compared to processes using only NH3. For samples S1–S5, for which the process temperature was 580 °C, the highest thicknesses of nitrided layers were found for samples S3–S5, for which NH3 or NH3 slightly diluted with H2 (from 34 to 41 µm) was used; this effect was particularly noticeable for sample S5, for which the heating time was extended (from 180 min to 360 min). Reducing the amount of ammonia or using larger hydrogen admixtures contributed to obtaining smaller layer thicknesses (S1–S2; 17–24 µm) while maintaining the same process parameters. In the case of the S6–S8 sample group, it was observed that processes carried out using different gas mixtures and different temperatures led to layers of the same thickness. The S6 process was carried out in an atmosphere of 40%NH3 + 60%N2, while the S7 process was carried out in an atmosphere of 90%NH3 + 10%H2. The high degree of dilution of ammonia with nitrogen in the S6 process caused a greater reduction in the nitrogen flow onto the nitrided surface than dilution with hydrogen in the S7 process. Hence, similar thicknesses of iron nitride layers were obtained on samples S6 and S7.

- In all of the gas nitriding processes, the nitrogen potential was at a high level during the process and decreased in the final stages. For samples S1–S5, it was observed that while maintaining the same process temperature, reducing the amount of NH3 led to the potential value decreasing first to levels characteristic of gamma nitrides, and then to the level of alpha nitrides. The use of 200 mL of NH3 or 190 mL of NH3 resulted in the potential not decreasing to the potential characteristic of α nitrides.

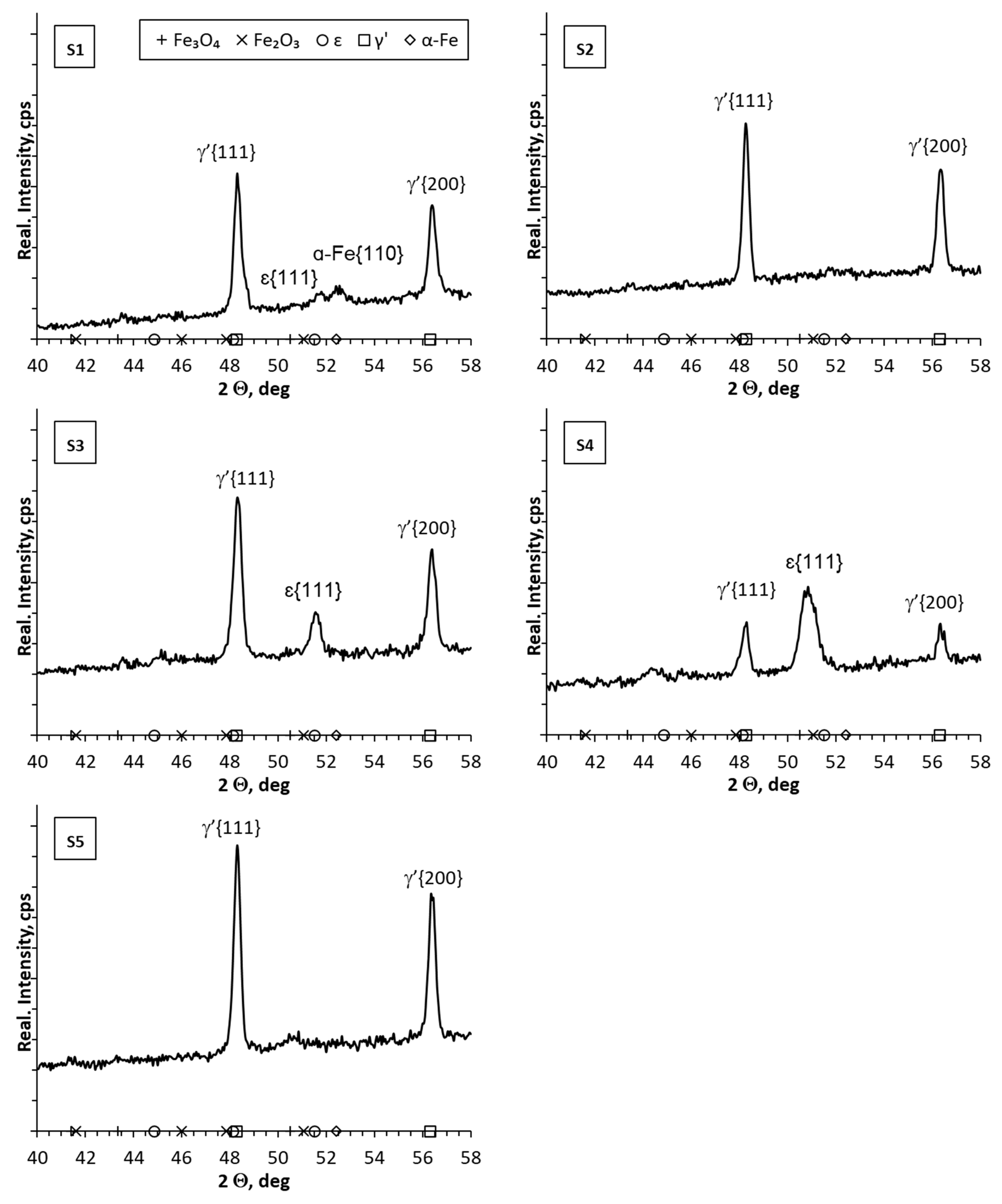

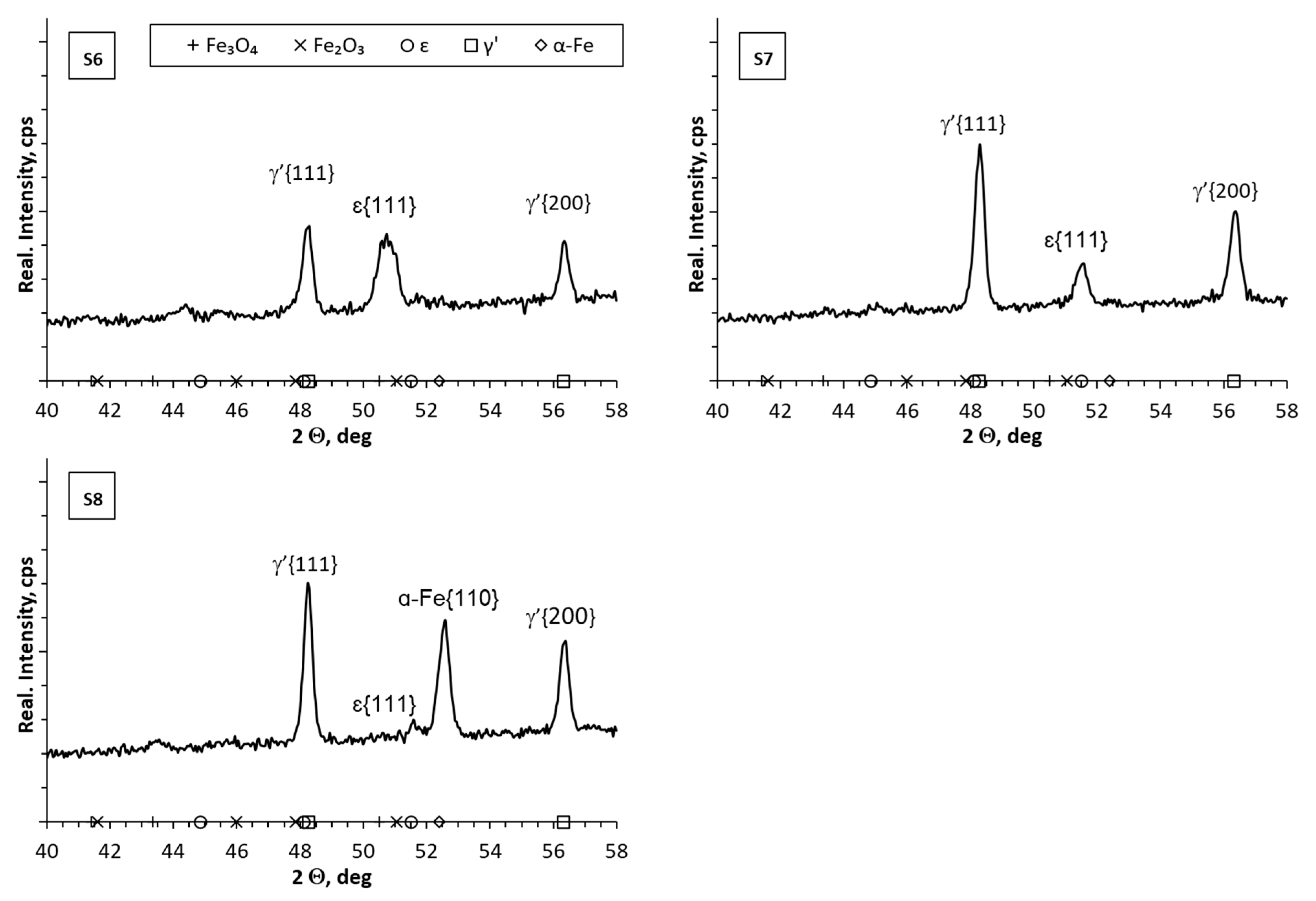

- The analysis of the diffractograms of the tested samples, despite some differences, generally indicates that when the nitrogen potential in the last stage of the process takes values in the α phase stability region, the result is a monophase γ’ layer.

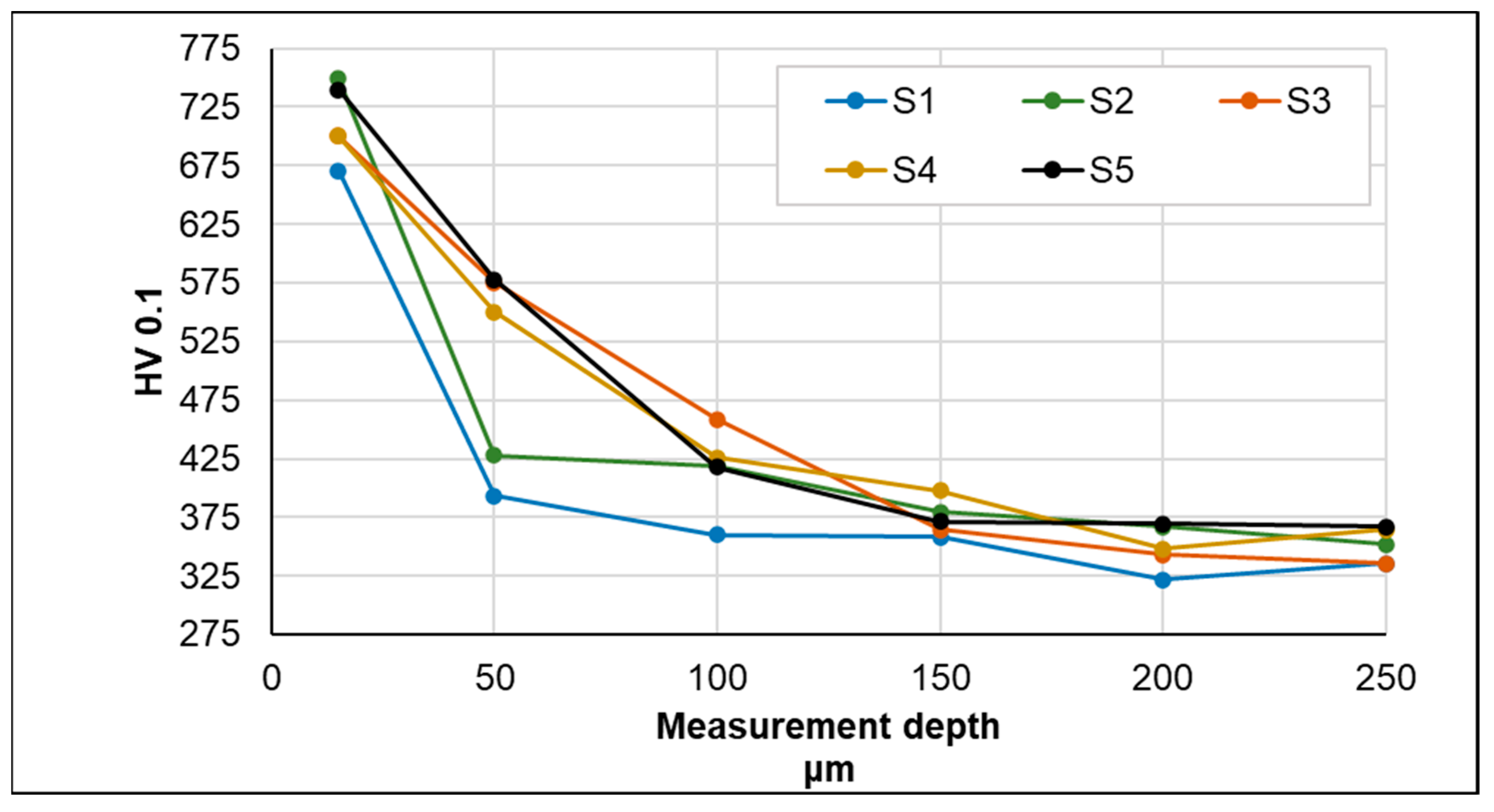

- The highest microhardness value was found for samples subjected to gas nitriding using pure NH3 or a gas mixture (NH3 + H2) with higher NH3 concentrations. At the same time, for these samples, the microhardness increased to a greater depth (approx. 50 μm).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zyśk, J. Rozwój Azotowania Gazowego Stopów Żelaza; Instytut Mechaniki Precyzyjnej: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duong Nam, N.; Anh Xuan, N.; Van Bach, N.; Nhung, L.T.; Chieu, L.T. Control Gas Nitriding Process: A Review. J. Mech. Eng. Res. Dev. 2019, 42, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittemeijer, E.J. Fundamentals of Nitriding and Nitrocarburizing. In Steel Heat Treating Fundamentals and Processes; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 619–646. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.; Sun, J.-Q.; Wang, X.-W.; He, Q.-K.; Si, J.-W.; Wang, D.-R.; Xie, K.; Li, W.-S. Effect of trace water in ammonia on breaking passive film of stainless steel during gas nitriding. Vacuum 2022, 202, 111216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.C.; Rosa, L.G.; Shohoji, N. Low-Temperature Nitriding of Va-Group Metal Powders (V, Nb, Ta) in flowing NH3 Gas under Heating with Concentrated Solar Beam at PSA. In Proceedings of the Materiais 2015: VII International Materials Symposium/XVII Conference of Sociedade Portuguesa dos Materiais, Book of Abstracts, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 June 2015; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Floe, C.F. A Study of the Nitriding Process. Trans. Am. Soc. Met. 1944, 32, 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bever, M.; Floe, C.F. Case hardening of steel by nitriding. Surf. Prot. Against Wear Corros. 1953, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, J.; Wołowiec-Korecka, E. A Study of Parameters of Nitriding Processes. Part 1. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2019, 61, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Wołowiec-Korecka, E. A Study of the Parameters of Nitriding Processes. Part 2. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2019, 61, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Burdyński, K.; Wach, P.; Łataś, Z. Nitrogen availability of nitriding atmosphere in controlled gas nitriding processes. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2015, 60, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małdziński, L.; Ostrowska, K.; Okoniewicz, P. Regulowane azotowanie gazowe ZeroFlow jako metoda zwiększająca trwałość matryc do wyciskania profili aluminiowych na gorąco. Obróbka Plast. Met. 2014, 25, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Małdziński, L. Termodynamiczne, Kinetyczne i Technologiczne Aspekty Wytwarzania Warstwy Azotowanej na Żelazie i Stalach w Procesach Azotowania Gazowego; nr 373.; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Poznańskiej: Poznań, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Sun, S.; Guo, M.; Jin, G.; Zhou, Z.; Fu, W. Study on pressurized gas nitriding characteristics for steel 38CrMoAlA. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2015, 279, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Lu, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, J.; Li, C. Wear and corrosion behavior of P20 steel surface modified by gas nitriding with laser surface engineering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 530, 147306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, H.; Huang, W.; Ding, Z.; Chen, D.; Cui, G. High-Efficient Gas Nitridation of AISI 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel by a Novel Critical Temperature Nitriding Process. Coatings 2023, 13, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januszewicz, B.; Wołowiec, E.; Kula, P. The Role of Carbides in Formation of Surface Layer on Steel X153CrMoV12 Due to Low-Pressure Nitriding (Vacuum Nitriding). Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2015, 57, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraczek, T.; Ogorek, M.; Skuza, Z.; Prusak, R. Mechanism of ion nitriding of 316L austenitic steel by active screen method in a hydrogen-nitrogen atmosphere. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 109, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K.; Dheeraj, B.; Sharma, Y.C. A Review on Plasma Ion Nitriding (PIN) Process. I-Manag. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, W.M.; Endan, J.B.; Yosuf, Y.A.; Shamsudin, R.; Ahmedov, A. High Pressure Processing Technology and Equipment Evolution: A Review. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2015, 8, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, T.; Prusak, R.; Ogórek, M.; Skuza, Z. The Effectiveness of Active Screen Method in Ion Nitriding Grade 5 Titanium Alloy. Materials 2021, 14, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frączek, T.; Prusak, R.; Ogórek, M.; Skuza, Z. Nitriding of 316L Steel in a Glow Discharge Plasma. Materials 2022, 15, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, M.; Frączek, T.; Skuza, Z. Application of active screen method for ion nitriding efficiency improvement. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2015, 60, 1075–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddam, M.; Kulka, M.; Makuch, N.; Ostrovska, K.; Maldzinski, L. Microstructure and Wear Resistance of Nitride Layers on Armco-Iron Obtained By Nitriding with Zero Gas Flow. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2023, 65, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygoński, T. Zeroflow®Gas Nitriding Is a Modern Technology That Minimizes the Consumption of Process Media and Reduces Emissions of Post-Process Gases; Seco Warwic S.A.: Świebodzin, Poland, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, J.; Wróblewski, E. Reducing Wear of Piston Rings Using Zero Flow Nitriding. J. KONES. Powertrain Transp. 2016, 23, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Małdziński, L. ZeroFlow—New, environmentally friendly method of controlled gas nitriding used for selected car parts. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 148, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronostajski, Z.; Widomski, P.; Kaszuba, M.; Zwierzchowski, M.; Polak, S.; Piechowicz, Ł.; Kowalska, J.; Długozima, M. Influence of the phase structure of nitrides and properties of nitrided layers on the durability of tools applied in hot forging processes. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 52, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, T.; Prusak, R.; Michalski, J.; Skuza, Z.; Ogórek, M. The Impact of Heating Rate on the Kinetics of the Nitriding Process for 52100 Steel. Materials 2023, 16, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Grade Steel | ɸ | Element Content in wt. % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm) | C | Mn | Si | P | S | |

| AISI 1085 | 3 | 0.80–0.93 | 0.70–1 | 0.07–0.6 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.05 |

| Sample No. | T (°C) | VT (K/min) | t (min) | NH₃ (mL/min) | H₂ (mL/min) | N₂ (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 580 °C | 25 | 180 | 150 | 20 | 0 |

| S2 | 185 | 15 | ||||

| S3 | 190 | 10 | ||||

| S4 | 200 | 0 | ||||

| S5 | 360 | |||||

| S6 | 570 °C | 10 | 180 | 120 | 180 | |

| S7 | 550 °C | 25 | 190 | 10 | 0 | |

| S8 | 490 °C | 240 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| voltage | 30 kV |

| current | 40 mA |

| step | 2θ 0.05° |

| counting time | 5 s |

| Range of diffraction angles | 40–58° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frączek, T.; Prusak, R.; Michalski, J.; Skuza, Z.; Ogórek, M. The Influence of Selected Process Parameters on the Efficiency of the Process of Gas Nitriding of AISI 1085 Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 2600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112600

Frączek T, Prusak R, Michalski J, Skuza Z, Ogórek M. The Influence of Selected Process Parameters on the Efficiency of the Process of Gas Nitriding of AISI 1085 Steel. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112600

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrączek, Tadeusz, Rafał Prusak, Jerzy Michalski, Zbigniew Skuza, and Marzena Ogórek. 2024. "The Influence of Selected Process Parameters on the Efficiency of the Process of Gas Nitriding of AISI 1085 Steel" Materials 17, no. 11: 2600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112600