Influence of Additives on the Macroscopic Color and Corrosion Resistance of 6061 Aluminum Alloy Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Coating Deposition Conditions

2.2. Microscopic Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

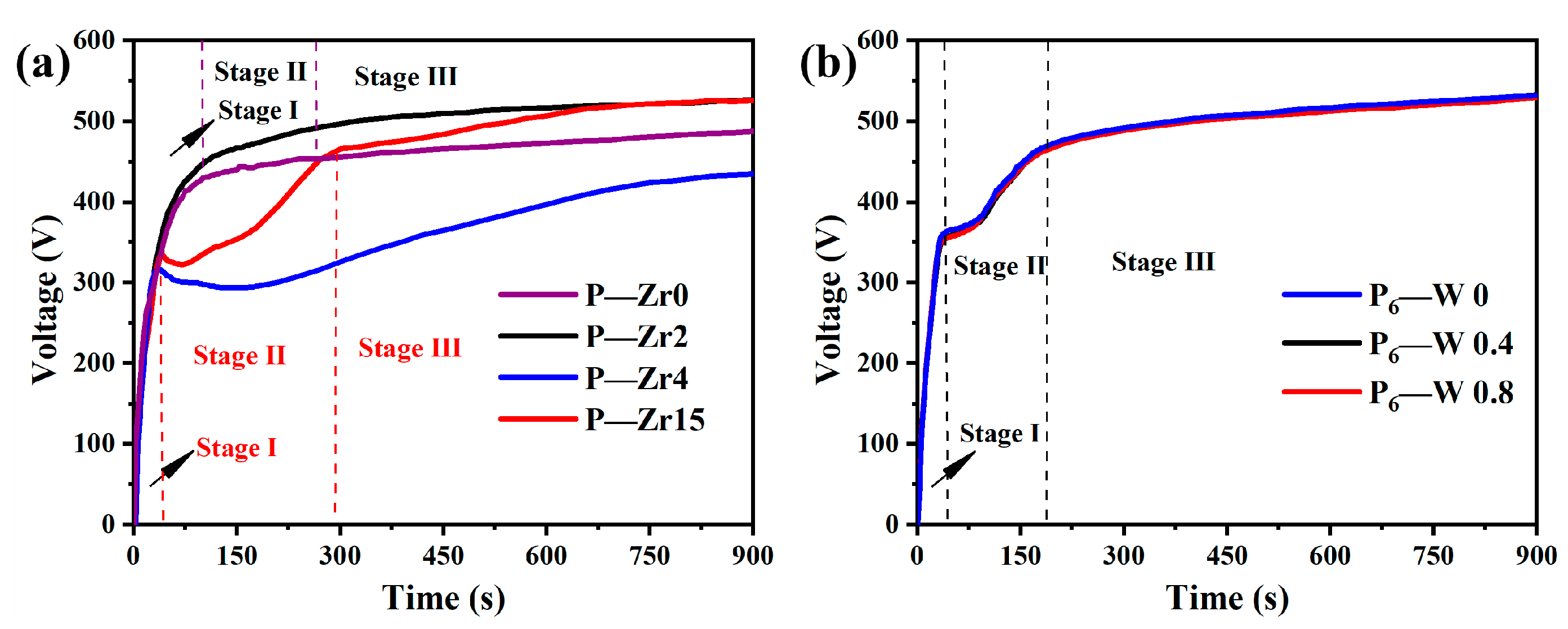

3.1. Voltage–Time Response

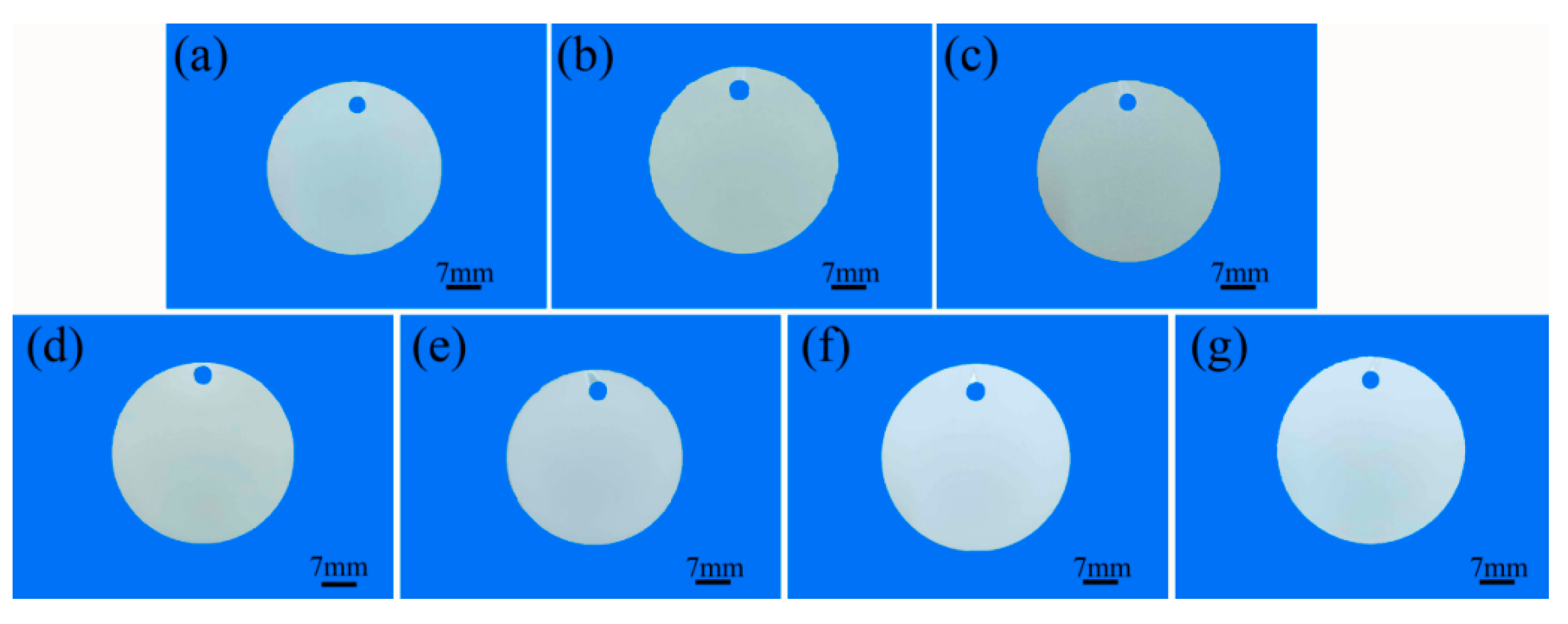

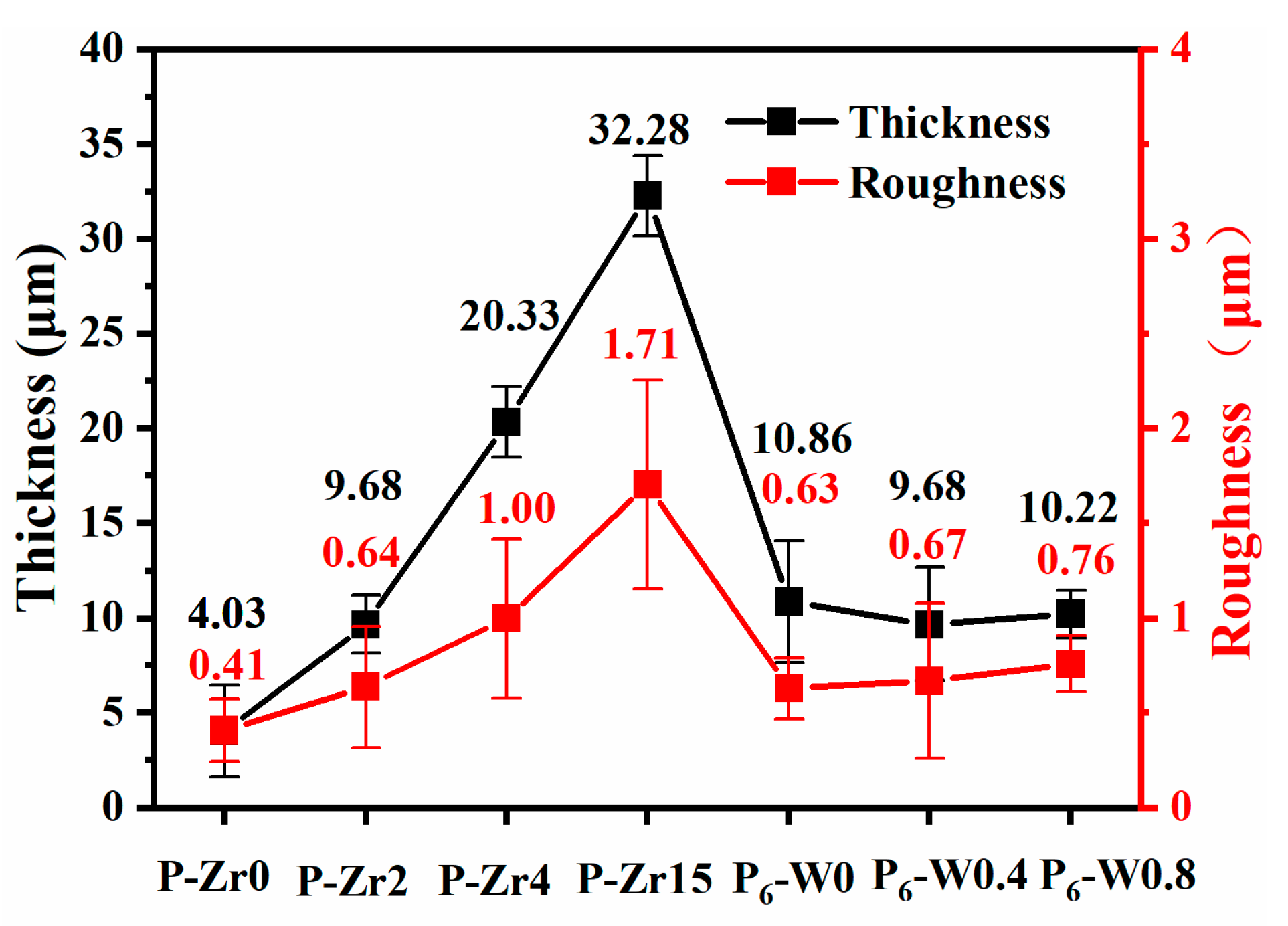

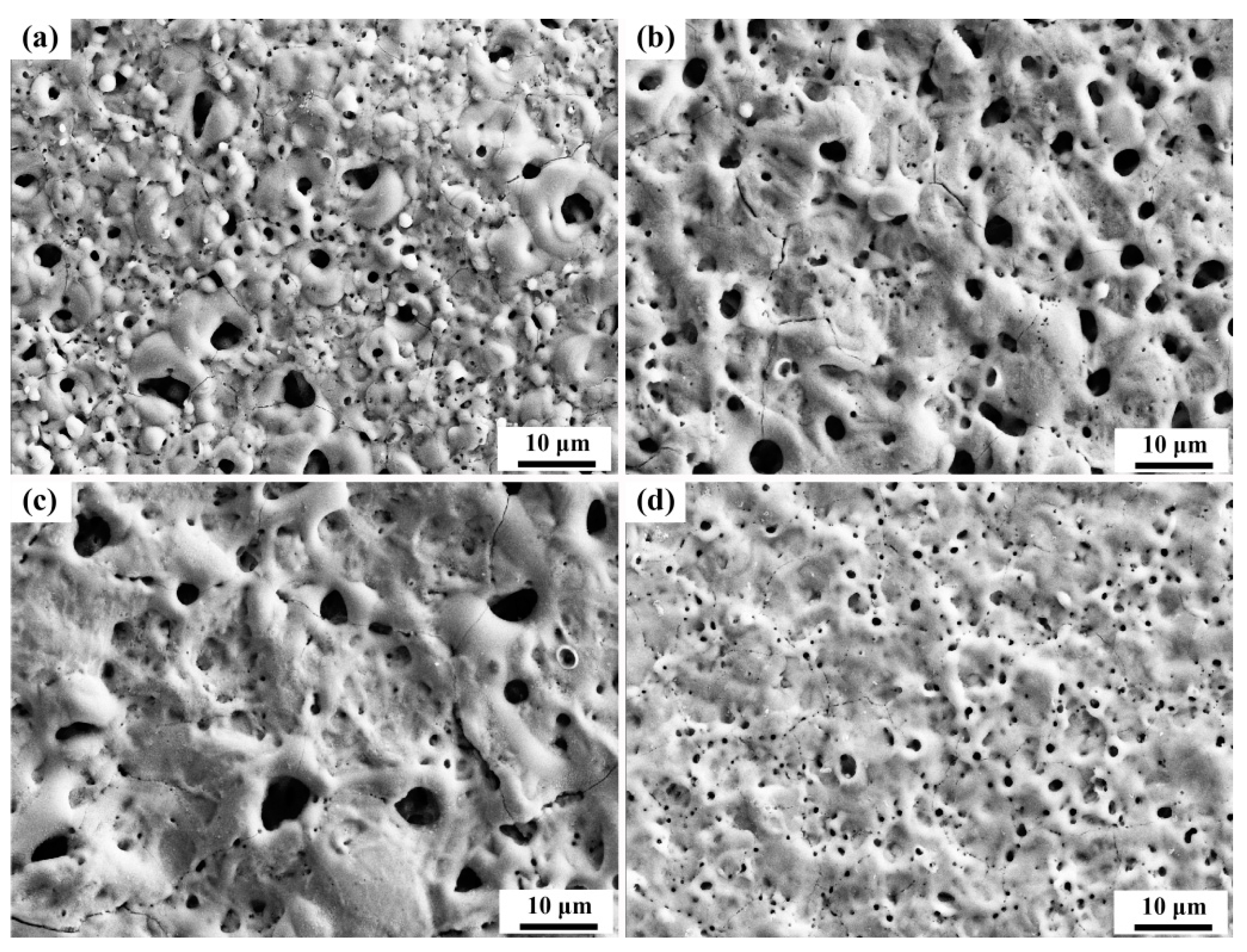

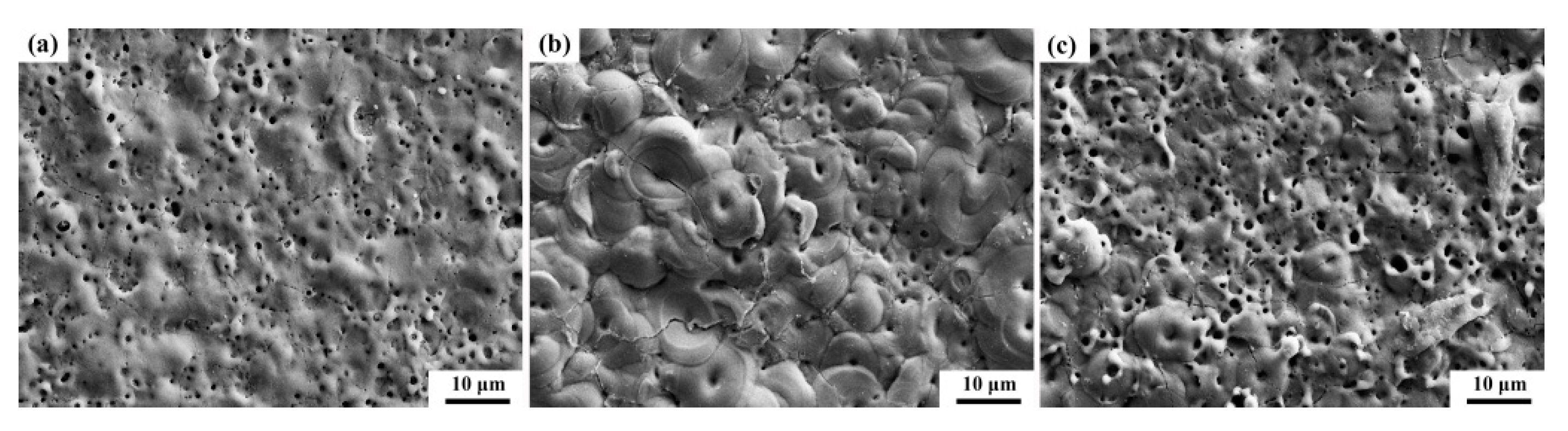

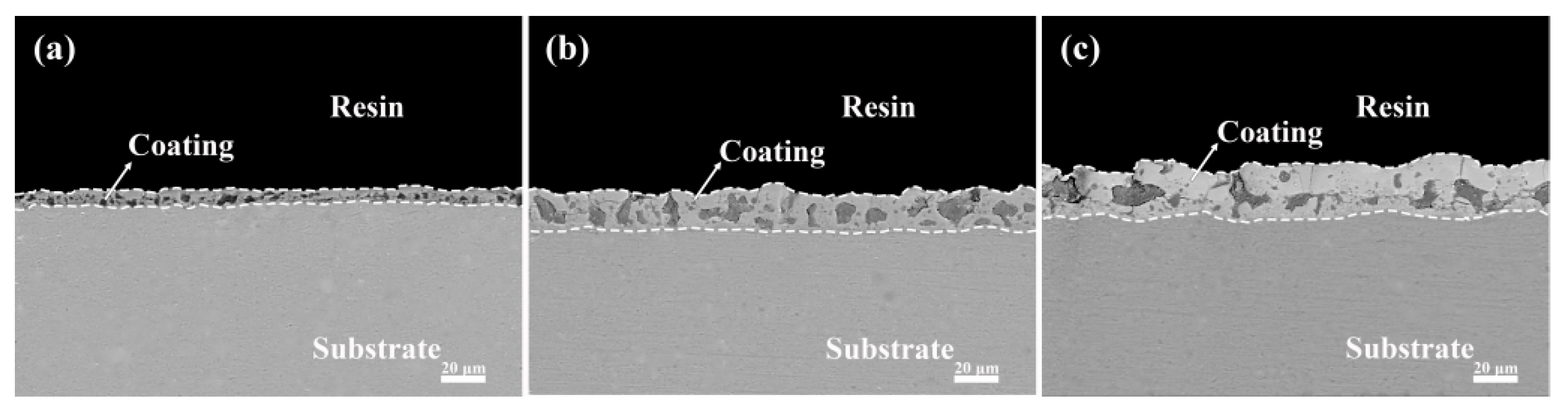

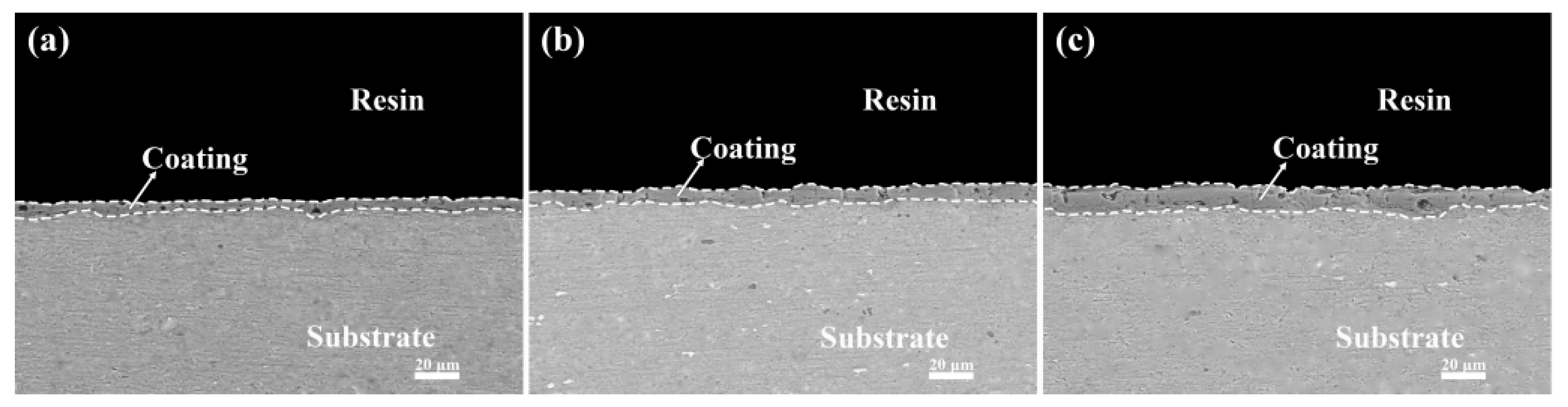

3.2. Effect of Different Additives on the Surface Structure and Micro-Structure of the Coatings

3.3. Effect of Various Additives on the Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum Alloy Coatings

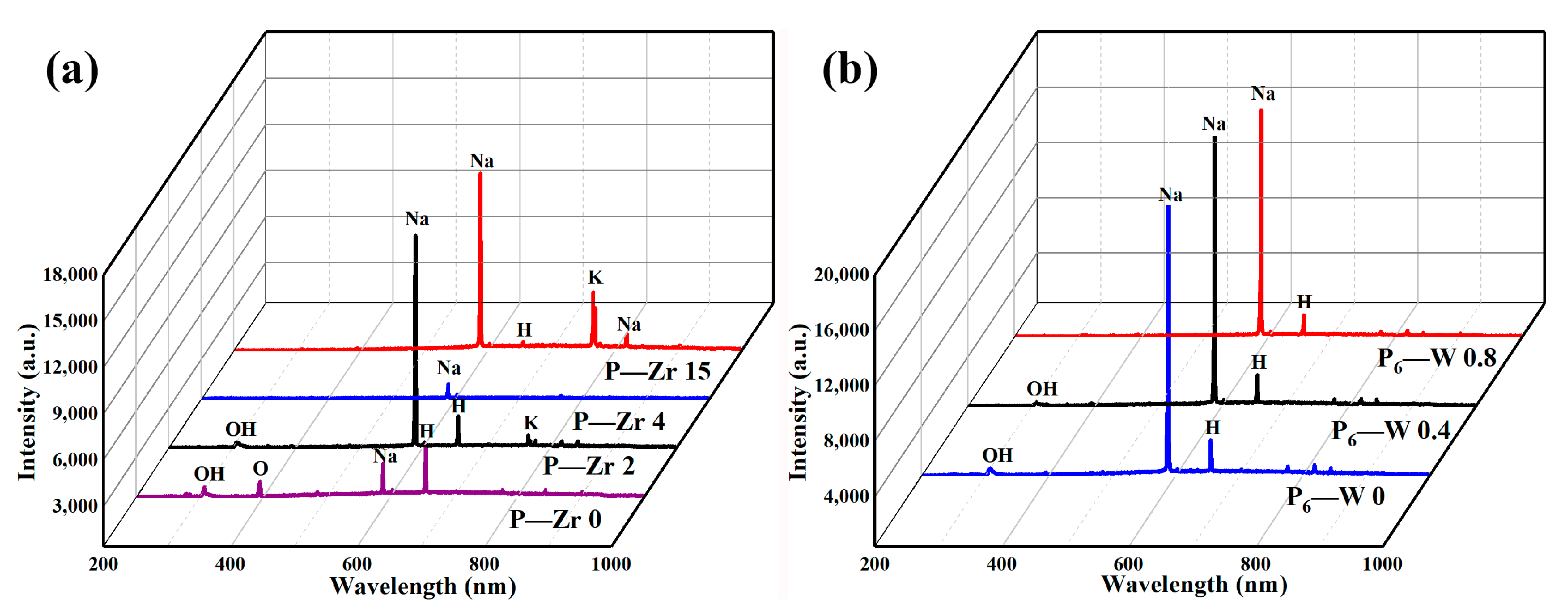

3.4. Coloring Analysis

3.5. Limitations and Future Research

4. Conclusions

- K2ZrF6 and Na2WO4 were fully dissolved and involved in the reaction, resulting in micro-arc oxidation coatings with L* values between 70 and 86 after adding the additives. A crystalline phase of ZrO2 appeared in the coating, which lightened the coating color, while a small amount of Na2WO4 did not form a crystalline phase, but the presence of elemental W in the coating darkened the coating color;

- The addition of additives to the coating during the reaction decreased its thermal stability due to the reduction of the crystalline phase compared to the coatings without the additives. However, the corrosion current decreased by one order of magnitude, indicating improved corrosion resistance. The addition of the additives not only enhanced the corrosion resistance of the coating but also increased its wear resistance, extending the service life of the aluminum alloy;

- The addition of additives inhibited the depletion of the Al substrate, and the crystalline phases α-Al2O3 and γ-Al2O3 in the coatings decreased with an increasing additive concentration. Moreover, the addition of the additives altered the discharge type, leading to changes in the coating surface morphology. The increased coating thickness and the presence of macropores in the K2ZrF6 solution laid the foundation for the thermal control performance of the coatings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goueffon, Y.; Mabru, C.; Labarrère, M.; Arurault, L.; Tonon, C.; Guigue, P. Mechanical behavior of black anodic films on 7175 aluminium alloy for space applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 204, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma Rani, R.; Sharma, A.K.; Mayanna, S.M.; Bhojraj, H.; Bhandari, D.R. Black permanganate conversion coatings on aluminium alloys for thermal control of spacecraft. Surf. Eng. 2005, 21, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K. Surface engineering for thermal control of spacecraft. Surf. Eng. 2005, 21, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunnellaiappan, T.; Rama, K.L.; Anoop, S.; Uma, R.R.; Rameshbabu, N. Fabrication of multifunctional black PEO coatings on AA7075 for spacecraft applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsangaraki-Kaplanoglou, I.; Theohari, S.; Dimogerontakis, T.; Kallithrakas-Kontos, N.; Wang, Y.-M.; Kuo, H.-H.; Kia, S. An investigation of electrolytic coloring process of anodized aluminum coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 2749–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-C.; Tsai, D.-S.; Wang, J.-M.; Chou, C.-C. Coloration of the aluminum alloy surface with dye emulsions while growing a plasma electrolytic oxide layer. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 287, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghith, M.; Arurault, L.; Bes, R.S. Selective Absorber Obtained by Nickel-Pigmented Anodized 6060 Aluminium Surface. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2012, 38, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagumothu, R.B.; Thangavelu, A.; Nair, A.M.; Sukumaran, A.; Anjilivelil, T. Development of Black Corrosion-Resistant Ceramic Oxide Coatings on AA7075 by Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2018, 72, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Nie, X.; Wang, L.; Northwood, D.O. Corrosion protection properties of anodic oxide coatings on an Al–Si alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 200, 1994–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cai, H.; Jiang, B. Growth mechanism of black ceramic layers formed by microarc oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 8702–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.-H.; Huang, Y.-C. Study on the black electrolytic coloring of anodized aluminum in cupric sulfate. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 208, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, W.; Zhang, G.; Guo, P. Preparation of black PEO layers on Al–Si alloy and the colorizing analysis. Vacuum 2015, 111, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Su, P.; Shen, Q.; Ju, P.; Wu, C.; Zhai, Y.; Jiang, Z. Preparation of thermal control coatings on Ti alloy by plasma electrolytic oxidation in K2ZrF6 solution. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 269, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L. Influence of K2TiF6 in electrolyte on characteristics of the microarc oxidation coating on aluminum alloy. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2012, 12, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Liang, J.; Chen, J. Thermal control coatings on magnesium alloys prepared by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 280, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.V.; Fazal, B.R.; Moon, S. Cerium- and phosphate-based sealing treatments of PEO coated AZ31 Mg alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 309, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, B.; Yao, Z.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Z. Preparation of a novel yellow ceramic coating on Ti alloys by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, I.L.; Coombs, B.D. Skin color measurements in terms of CIELAB color space values. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1992, 99, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Cao, J.; Mao, M.; Xie, H.; Skeldon, P. Key factors determining the development of two morphologies of plasma electrolytic coatings on an Al–Cu–Li alloy in aluminate electrolytes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 291, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, G.; Rama Krishna, L. Mechanisms underlying the formation of thick alumina coatings through the MAO coating technology. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 167, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, D. Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation Coatings of a 6061 Al Alloy in an Electrolyte with the Addition of K2ZrF6. Materials 2023, 16, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogov, A.B.; Huang, Y.; Shore, D.; Matthews, A.; Yerokhin, A. Toward rational design of ceramic coatings generated on valve metals by plasma electrolytic oxidation: The role of cathodic polarisation. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 34137–34158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Leyland, A.; Song, H.W.; Yerokhin, A.L.; Dowey, S.J.; Matthews, A. Thickness effects on the mechanical properties of micro-arc discharge oxide coatings on aluminium alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 116–119, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug Name | Chemical Formula | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Trisodium phosphate | Na₃PO₄ | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China) |

| Sodium silicate | Na2SiO3 | Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China) |

| Sodium Hexametaphosphate | (NaPO3)6 | Anhui Zhongxu Biotechnology Co. (Anhui, China) |

| Sodium tungstate | Na2WO₄ | Xilong Science Co. (Guangzhou, China) |

| Potassium Hexafluorozirconate | K2ZrF6 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. (Shanghai, China) |

| Specimen | Electrolyte | pH | Conductivity (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-Zr0 | 18 g/L Na3PO4 + 3 g/L Na2SiO3 + Corrosion inhibitor A | 5.34 | 10.41 |

| P-Zr2 | 18 g/L Na3PO4 + 3 g/L Na2SiO3 + 2 g/L K2ZrF6 + Corrosion inhibitor A | 5.40 | 11.15 |

| P-Zr4 | 18 g/L Na3PO4 + 3 g/L Na2SiO3 + 4 g/L K2ZrF6 + Corrosion inhibitor A | 5.28 | 11.80 |

| P-Zr15 | 18 g/L Na3PO4 + 3 g/L Na2SiO3 + 15 g/L K2ZrF6 + Corrosion inhibitor A | 5.35 | 15.75 |

| P6-W0 | 35 g/L (NaPO3)6 + 5 g/L Na2SiO3 | 6.77 | 11.88 |

| P6-W0.4 | 35 g/L (NaPO3)6 + 5 g/L Na2SiO3 + 0.4 g/L Na2WO4 | 6.42 | 12.46 |

| P6-W0.8 | 35 g/L (NaPO3)6 + 5 g/L Na2SiO3 + 0.8 g/L Na2WO4 | 6.25 | 12.88 |

| Specimen | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-Zr0 | 70.23 | 1.44 | 5.57 |

| P-Zr2 | 77.15 | 1.01 | 1.74 |

| P-Zr4 | 82.17 | 0.75 | 0.51 |

| P-Zr15 | 85.33 | 0.80 | 0.37 |

| P6-W0 | 75.18 | 0.76 | 2.92 |

| P6-W0.4 | 72.13 | 1.03 | 3.11 |

| P6-W0.8 | 69.67 | 1.42 | 5.86 |

| Specimen | Content of Elements (wt.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Al | Zr | W | |

| P-Zr0 | 53.20 | 46.80 | -- | -- |

| P-Zr2 | 47.92 | 42.45 | 9.63 | -- |

| P-Zr4 | 37.58 | 37.43 | 24.99 | -- |

| P-Zr15 | 27.36 | 17.39 | 55.25 | -- |

| P6-W0 | 55.37 | 44.63 | -- | -- |

| P6-W0.4 | 49.80 | 46.79 | -- | 3.41 |

| P6-W0.8 | 48.66 | 44.73 | -- | 6.61 |

| Specimen | Ecorr (mV vs. Ag/AgCl) | icorr (A/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| P6-W0 | −854 | 5.032 × 10−9 |

| P6-W0.8 | −801 | 8.960 × 10−10 |

| P-Zr0 | −832 | 1.064 × 10−8 |

| P-Zr15 | −1100 | 1.732 × 10−9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Chen, B. Influence of Additives on the Macroscopic Color and Corrosion Resistance of 6061 Aluminum Alloy Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings. Materials 2024, 17, 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112621

Chen X, Wang H, Liu C, Wang W, Chen B. Influence of Additives on the Macroscopic Color and Corrosion Resistance of 6061 Aluminum Alloy Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112621

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xuanyu, Hao Wang, Cancan Liu, Wenqiang Wang, and Bo Chen. 2024. "Influence of Additives on the Macroscopic Color and Corrosion Resistance of 6061 Aluminum Alloy Micro-Arc Oxidation Coatings" Materials 17, no. 11: 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112621