Quantifying Microstructure Features for High-Performance Solid Oxide Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SOFC Fabrication and Electrochemical Characterization

2.2. Focused Ion Beam–Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM)

2.3. 3D Data Pre-Processing

2.4. Pore and Grain Network Extraction

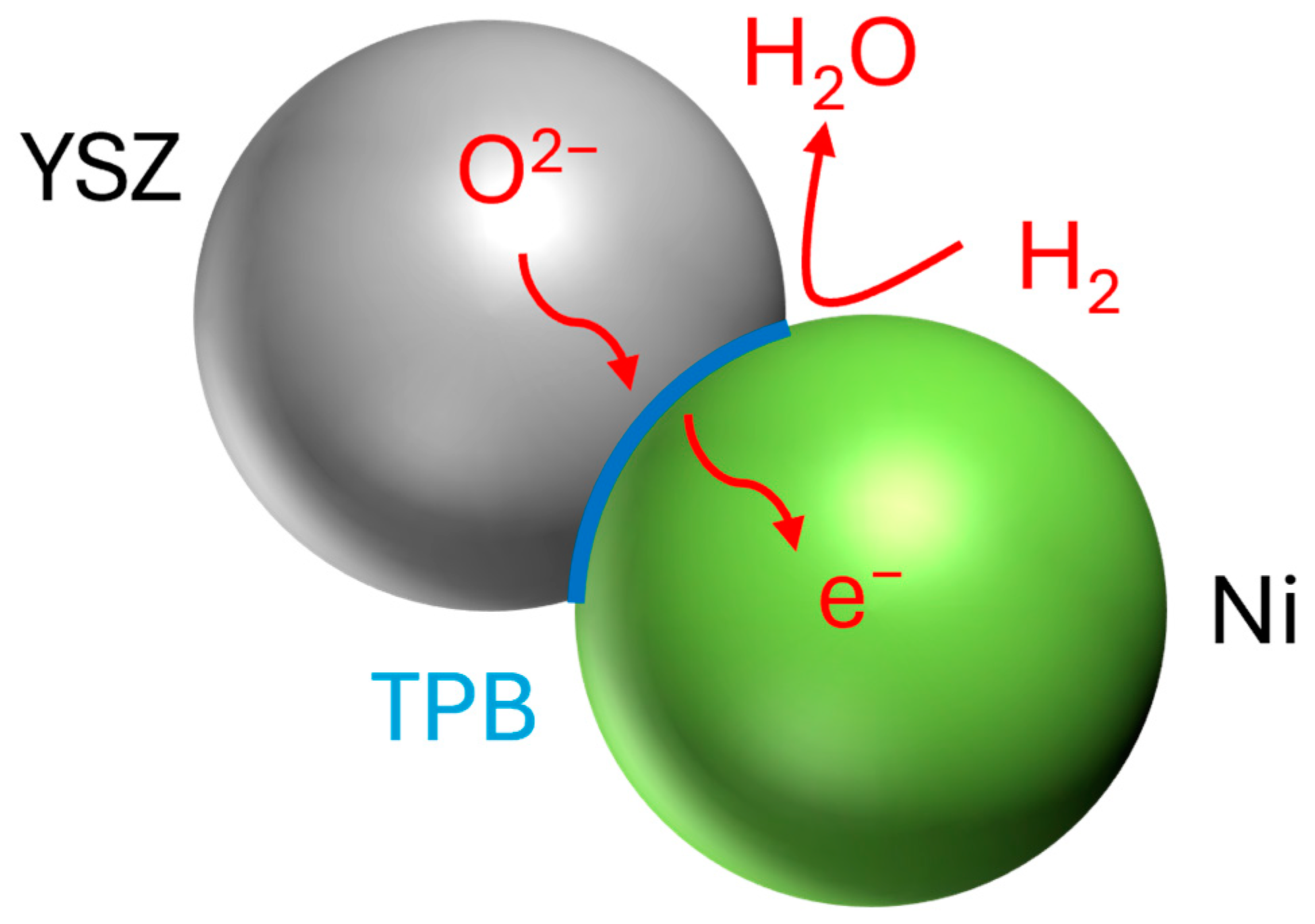

2.5. Triple-Phase Boundary (TPB) Identification and Quantification

2.6. Hydrogen Flow Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

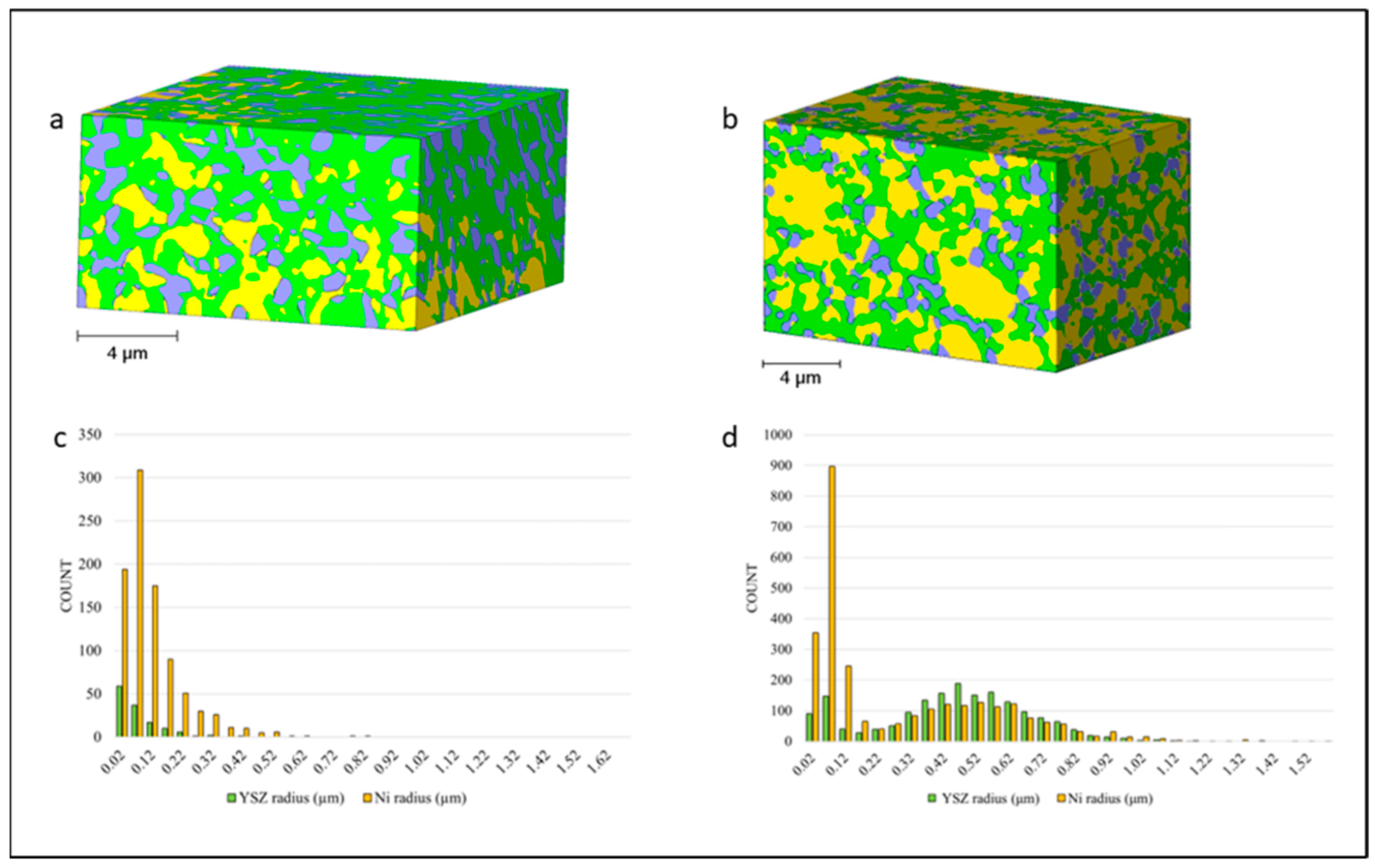

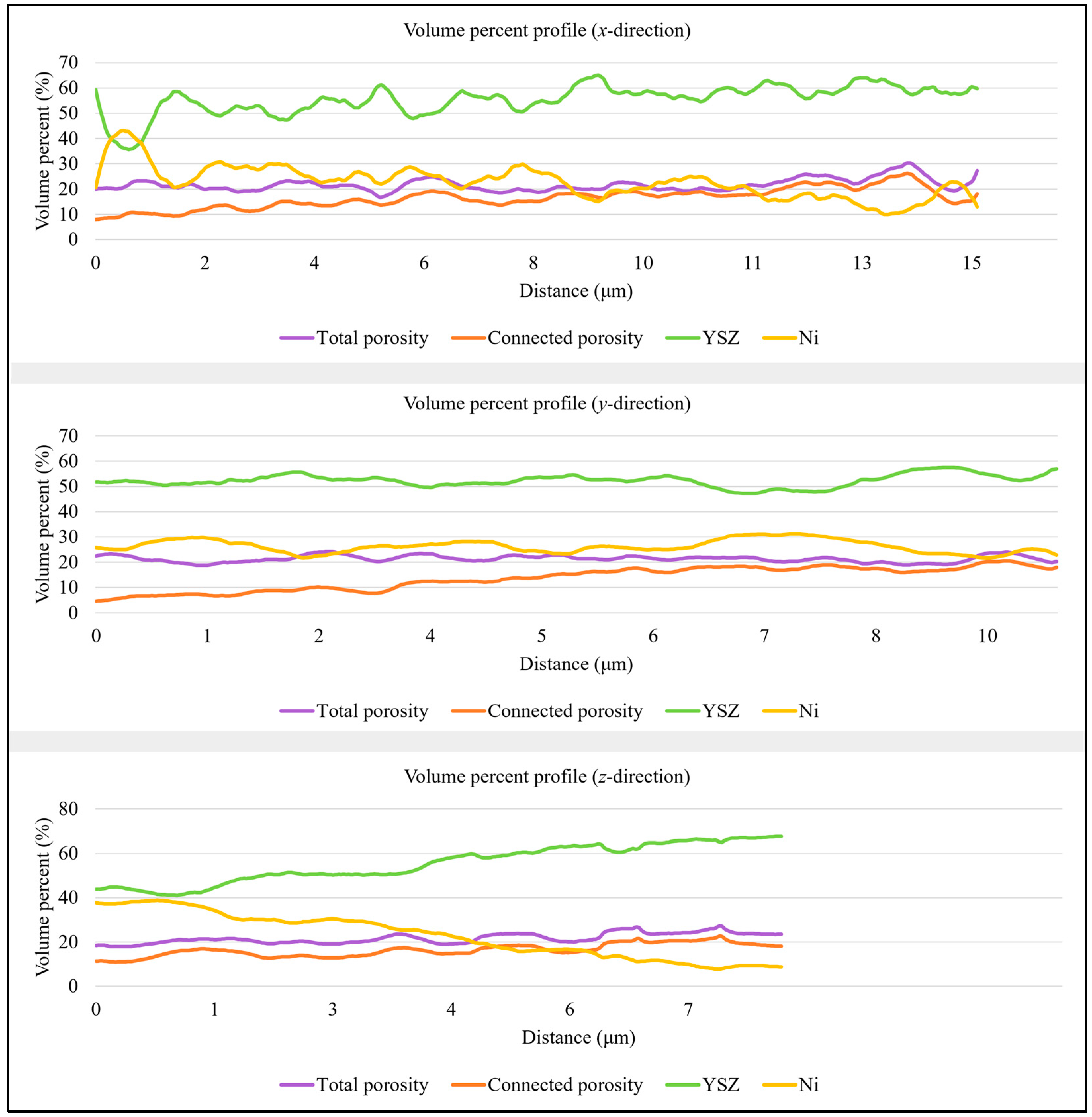

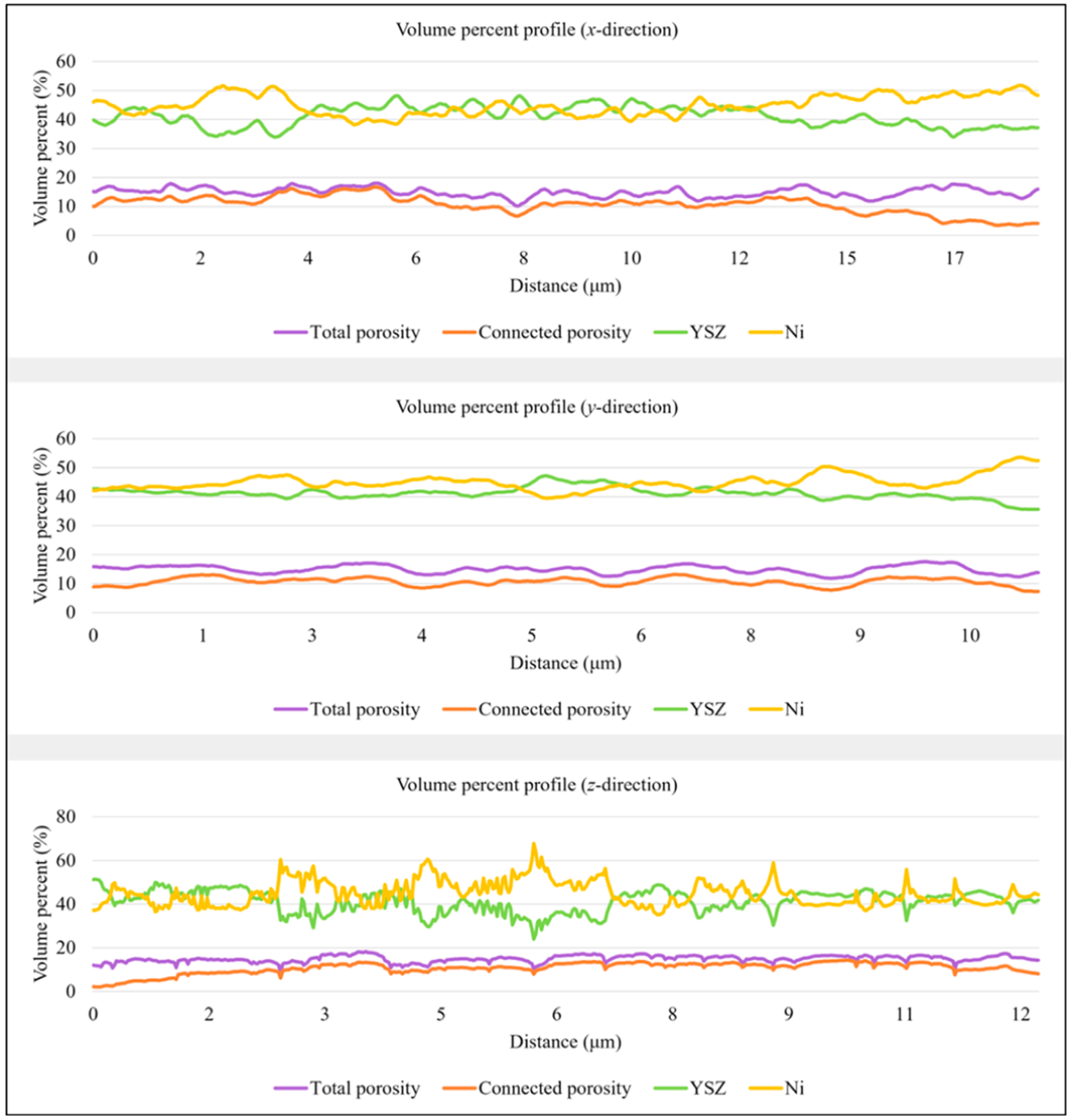

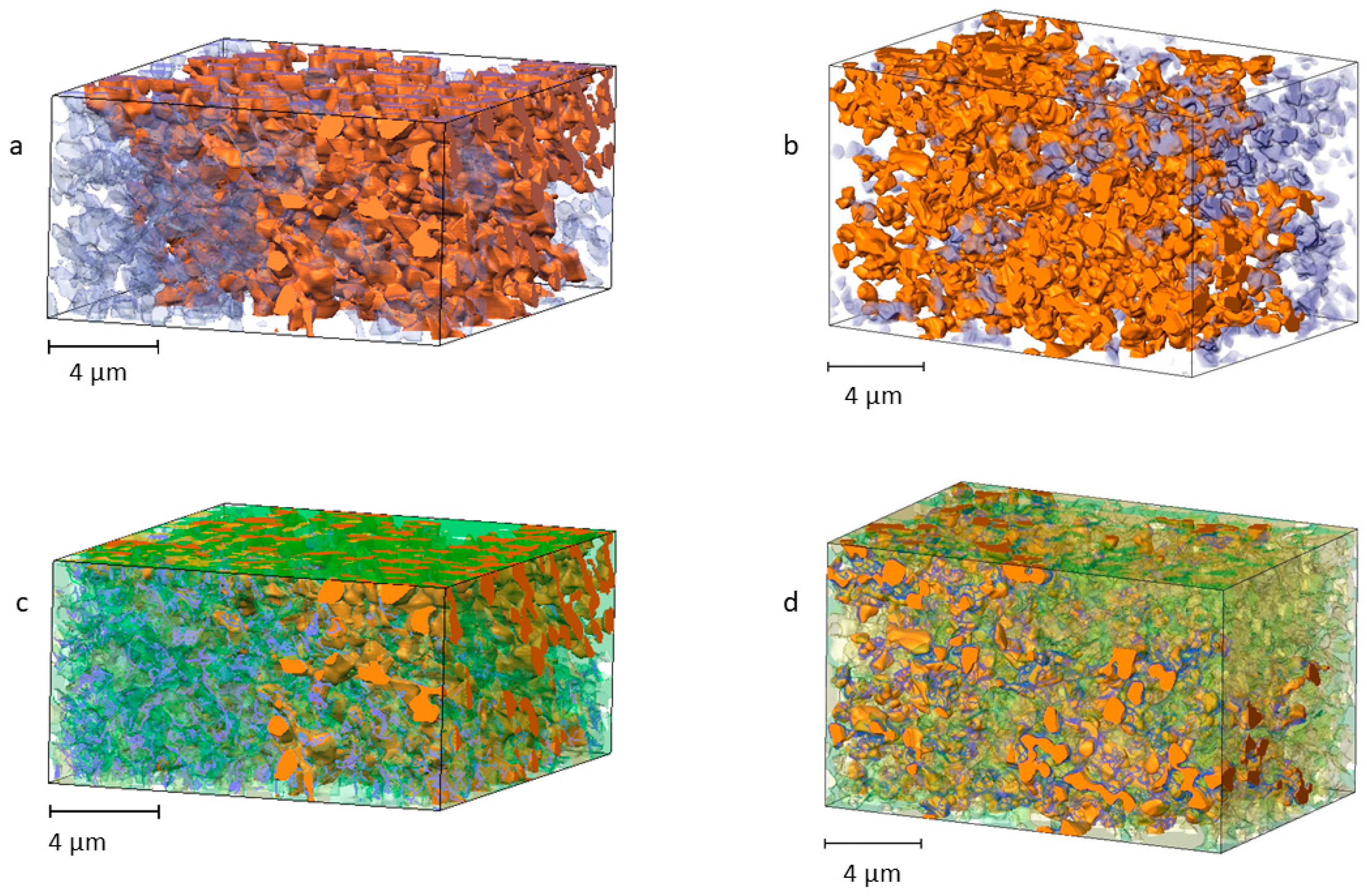

3.1. Anode Phase Reconstruction and Quantification

3.2. Connected Pore Space Modeling for TPB Characterization

3.3. Anode Permeability and Cell Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schneider, L.; Martin, C.; Bultel, Y.; Dessemond, L.; Bouvard, D. Percolation effects in functionally graded SOFC electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Wang, W.G. Electrochemical Analysis of an Anode-Supported SOFC. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 2330–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Pedersen, A.S. Electrolysis. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Management; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2014; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Vafaeenezhad, S.; Hanifi, A.R.; Laguna-Bercero, M.A.; Etsell, T.H.; Sarkar, P. Microstructure and long-term stability of Ni–YSZ anode supported fuel cells: A review. Mater. Futures 2022, 1, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkar, A.V.; Chen, J.; Tanner, C.W.; Kim, J.W. The role of electrode microstructure on activation and concentration polarizations in solid oxide fuel cells. Solid State Ion. 2000, 131, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Hasan, Z.; Funahashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Fujishiro, Y.; Awano, M. Impact of anode microstructure on solid oxide fuel cells. Science 2009, 325, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Z.; Lee, G.; Shikazono, N.; Kasagi, N. Quantitative Study on the Correlation Between Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Ni-YSZ Composite Anode Performance and Sintering Temperature Based on Three-dimensional Reconstruction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, F278–F286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertei, A.; Mertens, J.; Nicolella, C. Electrochemical Simulation of Planar Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Detailed Microstructural Modeling. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 146, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R.; Kobsiriphat, W.; Mendoza, R.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hiller, J.M.; Miller, D.J.; Thornton, K.; Voorhees, P.W.; Adler, S.B.; Barnett, S.A. Three-dimensional reconstruction of a solid-oxide fuel-cell anode. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukamp, B. Anodes sliced with ions. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearing, P.; Golbert, J.; Chater, R.; Brandon, N. 3D reconstruction of SOFC anodes using a focused ion beam lift-out technique. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 3928–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, H.; Shikazono, N.; Matsui, T.; Teshima, H.; Kishimoto, M.; Kishida, R.; Hayashi, D.; Matsuzaki, K.; Kanno, D.; Saito, M.; et al. Quantification of SOFC anode microstructure based on dual beam FIB-SEM technique. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivet, N.; Chupin, S.; Estrade, E.; Richard, A.; Bonnamy, S.; Rochais, D.; Bruneton, E. Effect of Ni content in SOFC Ni–YSZ cermets: A three-dimensional study by FIB-SEM tomography. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 9989–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Shikazono, N. 3D reconstruction size effect on the quantification of solid oxide fuel cell nickel-yttria-stabilized-zirconia anode microstructural information using scanning electron microscopy-focused ion beam technique. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, J.R.; Joshi, A.S.; Grew, K.N.; Chiu, W.K.S.; Tkachuk, A.; Wang, S.H.; Yun, W. Non-destructive Reconstruction and Analysis of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Anodes using X-ray Computed Tomography at sub-50 nm Resolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, B504–B508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heenan, T.M.M.; Bailey, J.J.; Lu, X.; Robinson, J.B.; Iacoviello, F.; Finegan, D.P.; Brett, D.J.L.; Shearing, P.R. Three-Phase Segmentation of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Anode Materials Using Lab Based X-ray Nano-Computed Tomography. Fuel Cells 2017, 17, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Heenan, T.M.M.; Bailey, J.J.; Li, T.; Li, K.; Brett, D.J.L.; Shearing, P.R. Correlation between triple phase boundary and the microstructure of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell anodes: The role of composition, porosity and Ni densification. J. Power Sources 2017, 365, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Virkar, A.V.; Fung, K.; Mehta, K.; Singhal, S.C. Polarization effects in intermediate temperature, anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.W.; Baskaran, S.; Chick, L.A.; Chou, Y.S.; Deibler, J.E.; Khaleel, M.A.; Marina, O.A.; Meinhardt, K.D.; Paxton, D.M.; Pederson, L.R.; et al. Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) Development at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Solid Oxide Fuel Cells, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2003; The Electrochemical Society: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 2003-07, pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, G.Y.; Virkar, A.V. The Effect of Electrode Microstructure on Cathodic Polarization; The Electrochemical Society: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2001; Volume 2001-16, pp. 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Fleig, J.; Maier, J. The Influence of Laterally Inhomogeneous Contacts on the Impedance of Solid Materials: A Three-Dimensional Finite-Element Study. J. Electroceram. 1997, 1, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.W.; Fung, K.; Virkar, A.V. The Effect of Porous Composite Electrode Structure on Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Performance: I. Theoretical Analysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmer, R. The Processing and Characterization of Porous Ni/YSZ and NiO/YSZ Composites Used in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, T.; Saraffi, M.H.; Haji, M.; Raissi, B.; Maghsoudipour, A. Investigation on microstructures of NiO–YSZ composite and Ni–YSZ cermet for SOFCs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 9440–9447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinkin, D.A.; Bronin, D.I.; Beresnev, S.M.; Bogdanovich, N.M.; Zhuravlev, V.D.; Vdovin, G.K.; Demyanenko, T.A. Thermal expansion, gas permeability, and conductivity of Ni-YSZ anodes produced by different techniques. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014, 18, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönleber, M.; Klotz, D.; Ivers-Tiffée, E. A Method for Improving the Robustness of linear Kramers-Kronig Validity Tests. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 131, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, L.; Iwanschitz, B.; Hocker, T.; Münch, B.; Prestat, M.; Wiedenmann, D.; Vogt, U.; Holtappels, P.; Sfeir, J.; Mai, A.; et al. Microstructure degradation of cermet anodes for solid oxide fuel cells: Quantification of nickel grain growth in dry and in humid atmospheres. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, B.S.; Kumar, S.S.; Aruna, S. Properties and development of Ni/YSZ as an anode material in solid oxide fuel cell: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sakane, Y.; Tsurumaki, T.; Ayame, Y.; Fujita, F. Microstructure and Electrical Conductivity of NI/YSZ Cermets for SOFC. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Composite Materials, Kyoto, Japan, 8–13 July 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Geagea, M.; Genov, I.; Stoynov, Z.; Vladikova, D.; Chesnaud, A.; Thorel, A. Permeability of Gases in the Anode of an Anode Supported SOFC. ECS Trans. 2015, 68, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T1 | Anode Phase | Volume Percent (vol.%) | Size (μm) | ||||

| Mean | STD x-Direction | STD y-Direction | STD z-Direction | Mean | STD | ||

| YSZ | 55.44 | 5.67 | 4.33 | 8.35 | 0.24 | 0.73 | |

| Ni | 22.86 | 6.40 | 4.54 | 10.03 | 0.24 | 0.27 | |

| Total porosity | 21.70 | 2.44 | 1.66 | 2.27 | - | - | |

| Connected porosity | 16.38 | 3.94 | 4.74 | 2.87 | 0.35 | 0.14 | |

| T2 | Anode Phase | Volume Percent (vol.%) | Size (μm) | ||||

| Mean | STD x-Direction | STD y-Direction | STD z-Direction | Mean | STD | ||

| YSZ | 41.21 | 3.53 | 2.01 | 4.92 | 0.42 | 0.23 | |

| Ni | 44.95 | 3.43 | 2.68 | 5.61 | 0.26 | 0.28 | |

| Total porosity | 14.91 | 1.56 | 1.40 | 1.55 | - | - | |

| Connected porosity | 10.65 | 3.08 | 1.36 | 2.64 | 0.31 | 0.11 | |

| T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample volume (μm3) | 2363.11 | 2568.59 |

| TPB length (μm) | 4618.99 | 10,062.40 |

| TPB density (μm−2) | 1.96 | 3.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruse, C.M.; Hume, L.A.; Wang, Y.; Pesacreta, T.C.; Zhou, X.-D. Quantifying Microstructure Features for High-Performance Solid Oxide Cells. Materials 2024, 17, 2622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112622

Ruse CM, Hume LA, Wang Y, Pesacreta TC, Zhou X-D. Quantifying Microstructure Features for High-Performance Solid Oxide Cells. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112622

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuse, Cristina Mariana, Lily Ann Hume, Yudong Wang, Thomas C. Pesacreta, and Xiao-Dong Zhou. 2024. "Quantifying Microstructure Features for High-Performance Solid Oxide Cells" Materials 17, no. 11: 2622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112622