The Development of Novel Cu/GO Nano-Composite Coatings by Brush Plating with High Wear Resistance for Potential Brass Sliding Bearing Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate Materials and Coating Solutions

2.2. Cu and Cu/GO Coating Processes

2.3. Characterisations of Coating Structures

2.4. Tribological Test

3. Results

3.1. Surface Morphology and Roughness

3.2. Layer Structure of the Coatings

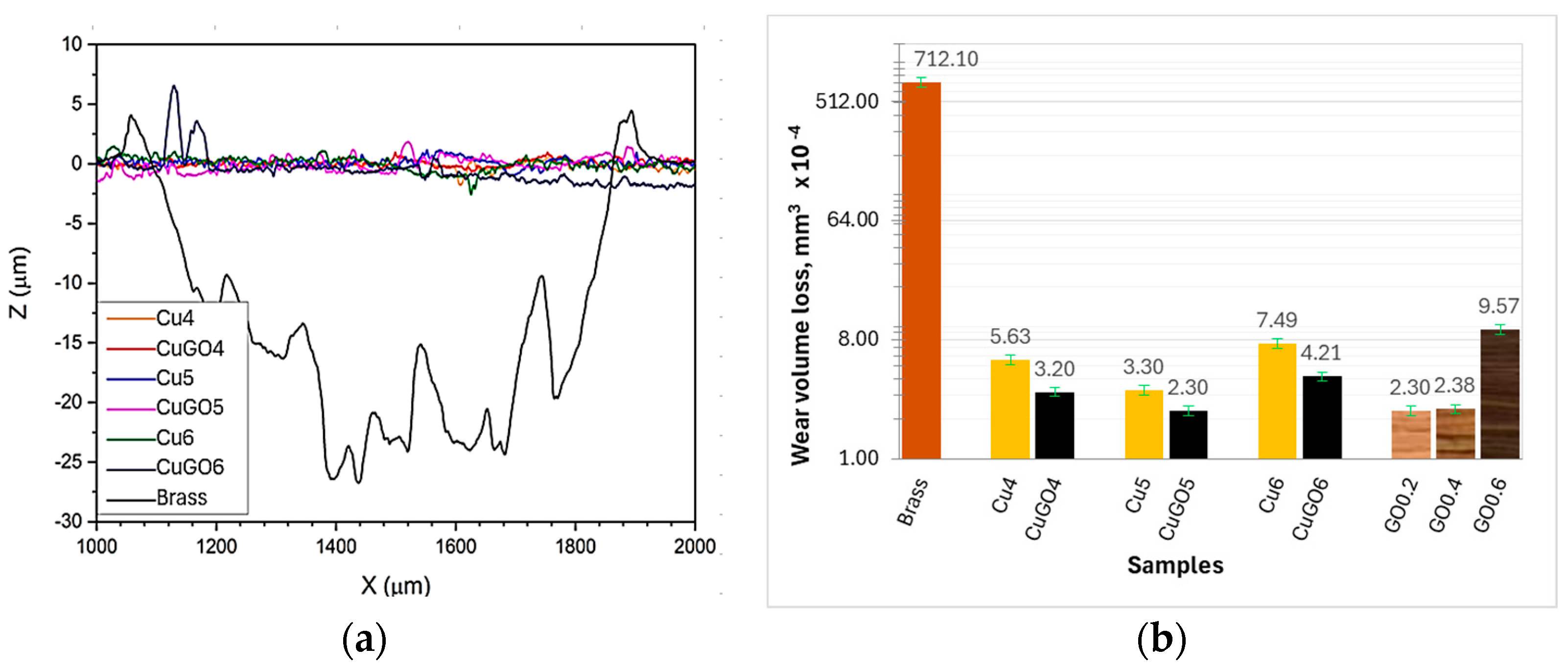

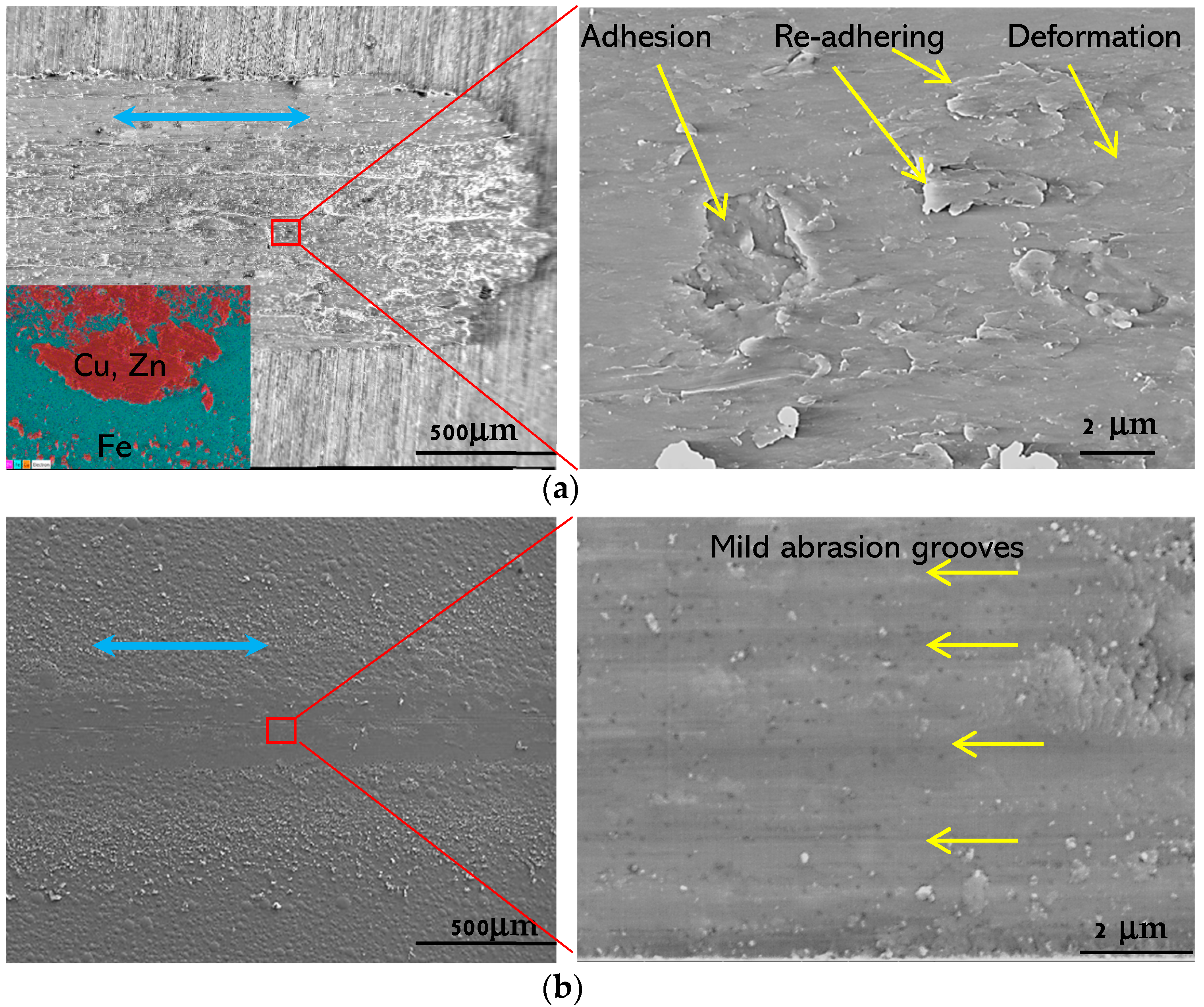

3.3. Tribological Properties of the Coatings

4. Discussion

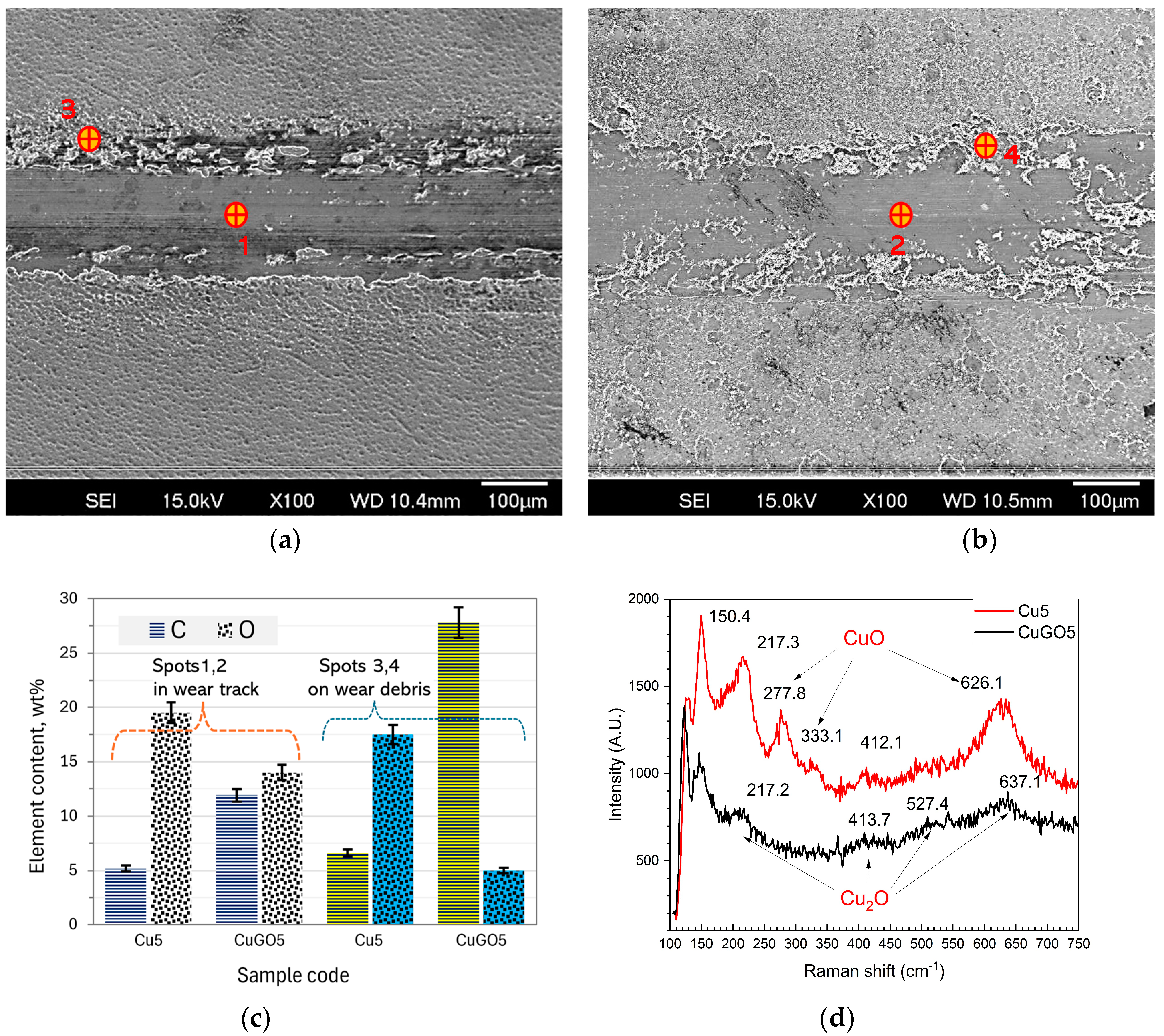

4.1. Tribological Property Improvements of Cu and CuGO Coatings

4.2. Optimal Brush Plating Conditions for Wear Resistance Coatings

5. Conclusions

- The research demonstrated the fabrication of thick (>19.2 μm) GO/Cu composite coatings with good adhesive to the substrate on brass by brush plating under voltage equal to and higher than 4 V.

- The detailed characterisation of the brush-plated coating by SEM, EDX and GDOES revealed that GO can be successfully introduced across the whole composite coating layer.

- The GO/Cu composite coatings produced under 5 V (GO/Cu5) and 6 V (GO/Cu6) can reduce friction and increase the wear resistance by two orders of magnitude compared to brass, mainly due to the self-lubricating of the GO added into the coatings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boopathi, M.; Shankar, S.; Manikandakumar, S.; Ramesh, R. Experimental Investigation of Friction Drilling on Brass, Aluminium and Stainless Steel. Procedia Eng. 2013, 64, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, P.K.; Ray, S.; Liu, Y. Tribological properties of metal matrix-graphite particle composites. Int. Mater. Rev. 1992, 37, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.; Erdemir, A.; Sumant, A.V. Graphene: A new emerging lubricant. Mater. Today 2014, 17, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Martin, J.-M.; Lee, R. Influence of oxides on friction during Cu CMP. J. Electron. Mater. 2001, 30, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazar, S.; Bagheri, S.; Abd Hamid, S.B. Enhancing lubricant properties by nanoparticle additives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 3153–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrul, M.; Zulkifli, N.W.M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A. Tribological Properties and Lubricant Mechanism of Nanoparticle in Engine Oil. Procedia Eng. 2013, 68, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Kheireddin, B.; Gao, H.; Liang, H. Roles of nanoparticles in oil lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2016, 102, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, D.; Cui, Y. The development of a Cu@Graphite solid lubricant with excellent anti-friction and wear resistant performances in dry condition. Wear 2022, 488–489, 204181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Application of graphene oxide in water treatment. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 94, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathy, Y.; Kamboj, A.; Rekha, M.Y.; Rao, N.N.; Srivastava, C. Copper-graphene oxide composite coatings for corrosion protection of mild steel in 3.5% NaCl. Thin Solid Film. 2017, 636, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, A.K.; Mallik, A. Ultrasound assisted electroplating of nano-composite thin film of Cu matrix with electrochemically in-house synthesized few layer graphene nano-sheets as reinforcement. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 750, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Sun, S.; Ge, S.; Guo, X.; Xie, F.; Jiang, B.; Wujcik, E.K.; et al. Silver nanoparticles/graphene oxide decorated carbon fiber synergistic reinforcement in epoxy-based composites. Polymer 2017, 131, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xu, B.S.; Zhang, B.; Jing, X.D.; Liu, C.L. Automatic brush plating: An update on brush plating. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, H.; Dong, S.; Bin, J. Fretting wear-resistance of Ni-base electro-brush plating coating reinforced by nano-alumina grains. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 710–713. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, H.; Xu, G.; Li, C. Graphene oxide in aqueous and nonaqueous media: Dispersion behaviour and solution chemistry. Carbon 2020, 158, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, B. Rafael Muñoz-Carpena etc., Aggregation Kinetics of Graphene Oxides in Aqueous Solutions:Experiments, Mechanisms, and Modeling. Langmuir 2013, 29, 15174–15181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, H. Fabrication and characterisation of electro-brush plated nickel-graphene oxide nano-composite coatings. Thin Solid Films. 2017, 644, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/uk/en/home/electron-microscopy/products/scanning-electron-microscopes/apreo-sem.html (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Available online: https://www.icdd.com/pdfsearch/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Moshkovich, A.; Perfilyev, V.; Lapsker, I.; Rapoport, L. Friction, wear and plastic deformation of Cu and α/β brass under lubrication conditions. Wear 2014, 320, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Liao, X.Z.; Zhu, Y.T.; Horita, Z.; Langdon, T.G. Influence of stacking fault energy on nanostructure formation under high pressure torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 410–411, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshi, L.; Samuha, S.; Cohen, S.R.; Laikhtman, A.; Moshkovich, A.; Perfilyev, V.; Lapsker, I.; Rapoport, L. Dislocation structure and hardness of surface layers under friction of copper in different lubricant conditions. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Handoko, A.D.; Du, Y.; Xi, S.; Yeo, B.S. In Situ Raman Spectroscopy of Copper and Copper Oxide Surfaces during Electrochemical Oxygen Evolution Reaction: Identification of CuIII Oxides as Catalytically Active Species. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Operation | Solution | Voltage/V | Time/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Electrical active-clean | Active-cleaning solution | 7 | 3 |

| 2 | Nickel strike | Special nickel solution | 7 | 3 |

| 3 | Final plating | Cu or Cu + GO solutions (0.2–0.6 g/L) | 2–6 | 30 |

| Group | Sample Code | Plating Solution | Plating Voltage/V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | CuGO | Cu | CuGO | ||

| 1 | Cu2 | CuGO2 | Cu | Cu + GO (0.2 g/L) | 2 |

| Cu3 | CuGO3 | 3 | |||

| Cu4 | CuGO4 | 4 | |||

| Cu5 | CuGO5 | 5 | |||

| Cu6 | CuGO6 | 6 | |||

| 2 | GO0.2 | Cu + GO (0.2 g/L) | 5 | ||

| GO0.4 | Cu + GO (0.4 g/L) | ||||

| GO0.6 | Cu + GO (0.6 g/L) | ||||

| GO0.8 | Cu + GO (0.8 g/L) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, H. The Development of Novel Cu/GO Nano-Composite Coatings by Brush Plating with High Wear Resistance for Potential Brass Sliding Bearing Application. Materials 2024, 17, 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112623

Feng Y, Li X, Dong H. The Development of Novel Cu/GO Nano-Composite Coatings by Brush Plating with High Wear Resistance for Potential Brass Sliding Bearing Application. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112623

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yingdi, Xiaoying Li, and Hanshan Dong. 2024. "The Development of Novel Cu/GO Nano-Composite Coatings by Brush Plating with High Wear Resistance for Potential Brass Sliding Bearing Application" Materials 17, no. 11: 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112623

APA StyleFeng, Y., Li, X., & Dong, H. (2024). The Development of Novel Cu/GO Nano-Composite Coatings by Brush Plating with High Wear Resistance for Potential Brass Sliding Bearing Application. Materials, 17(11), 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112623