Influence of Excitation Parameters on Finishing Characteristics in Magnetorheological Finishing for 6063 Aluminum Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Principle and Setup

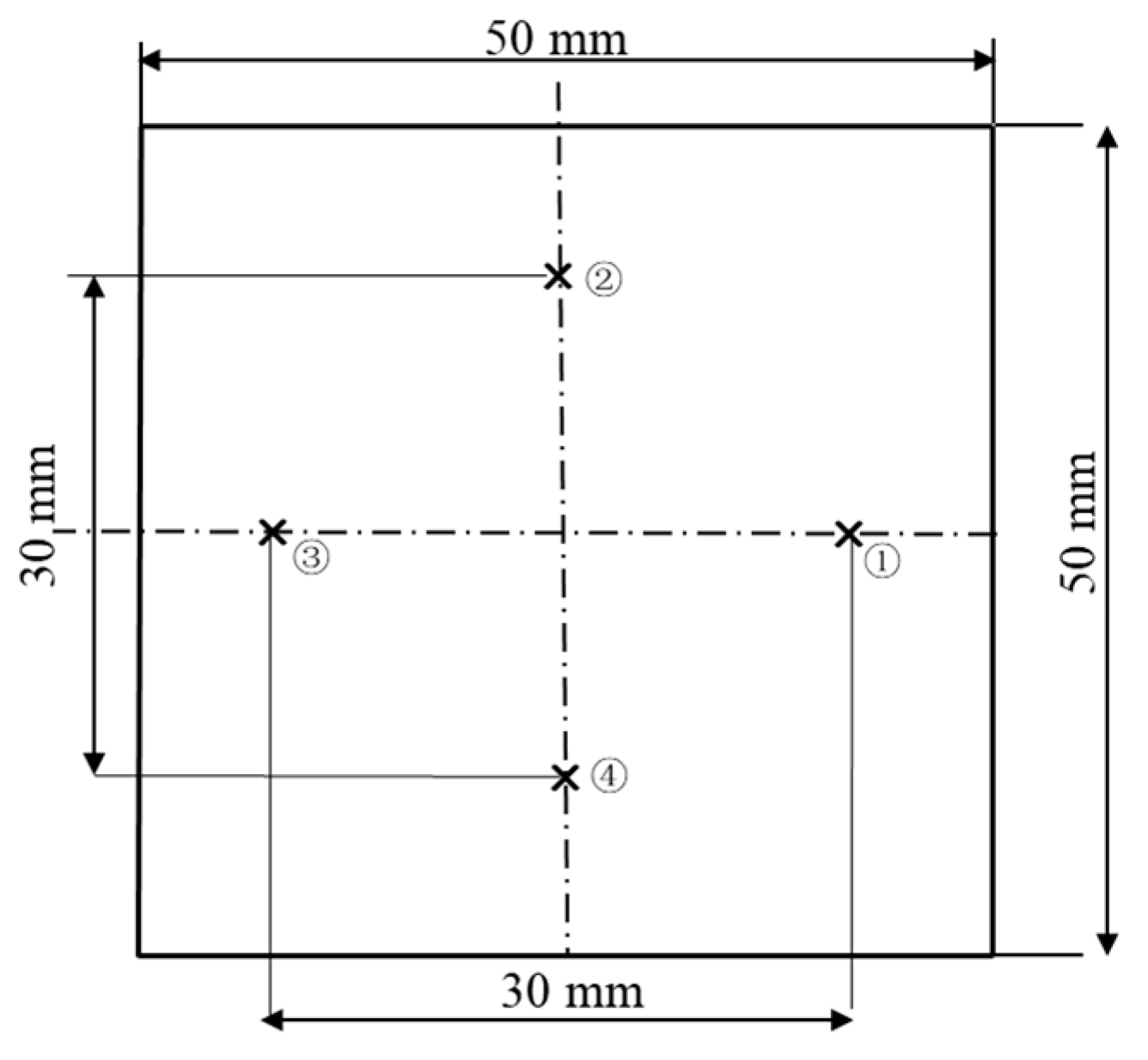

2.2. Experimental Method and Conditions

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

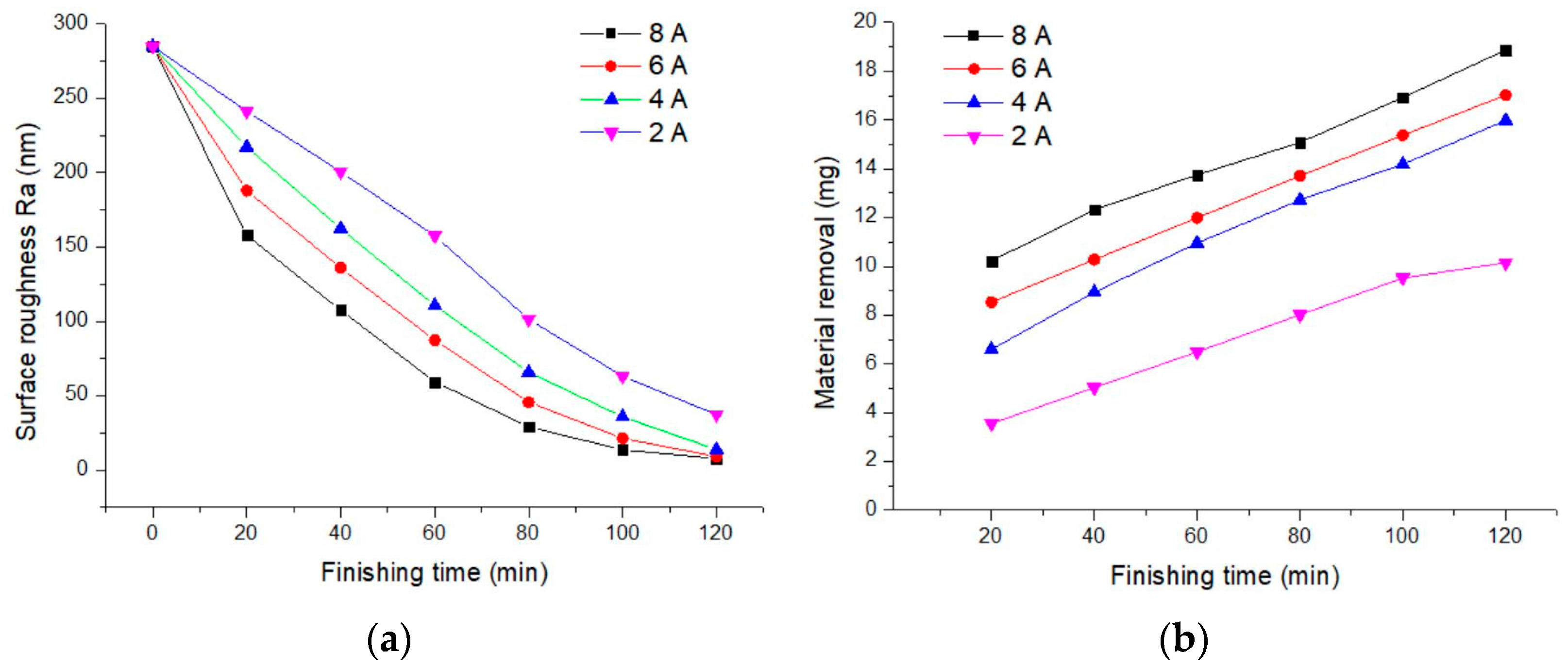

3.1. Current

3.2. Frequency

3.3. Excitation Gap

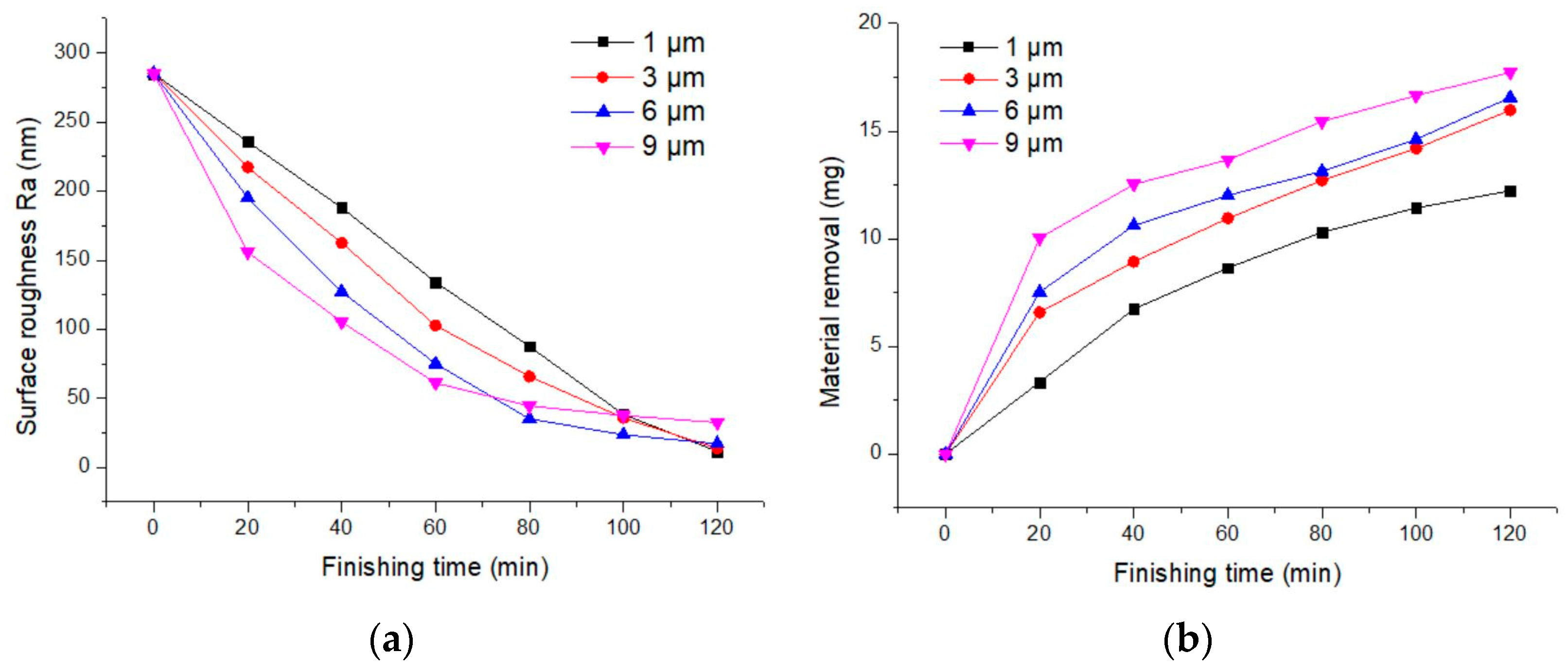

3.4. Iron Powder Particle Size

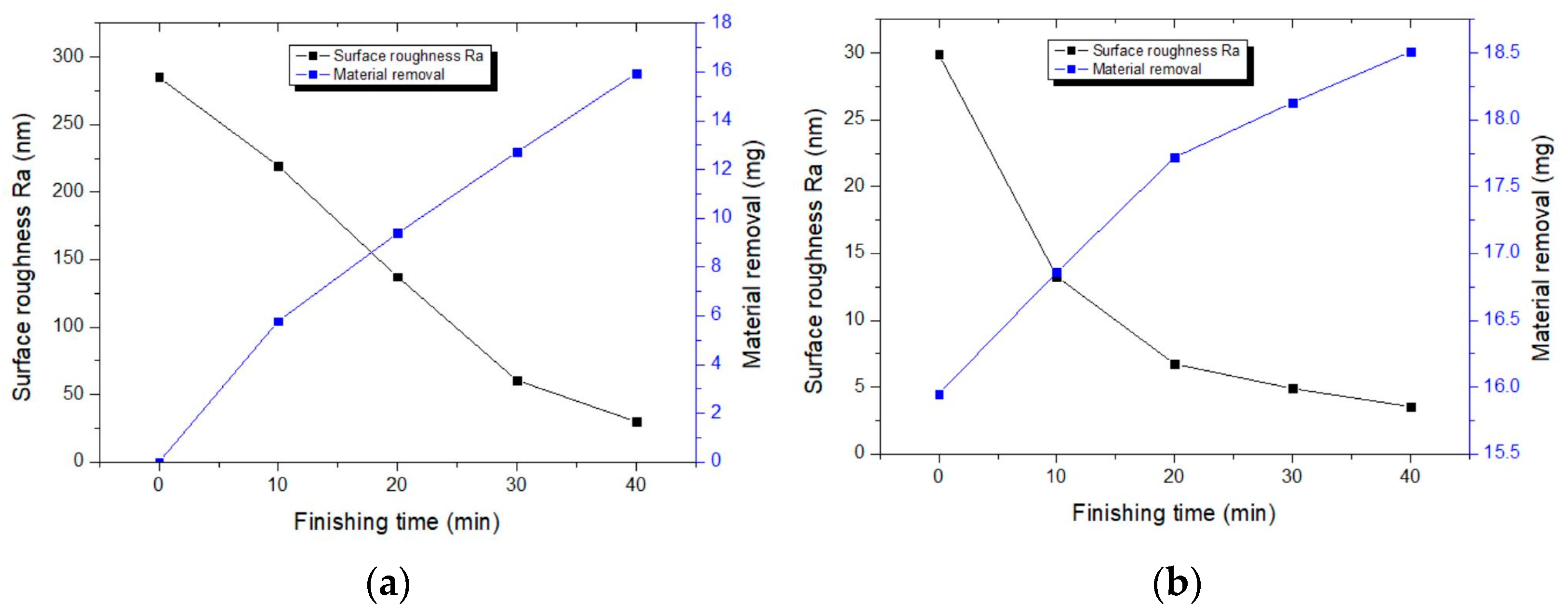

3.5. Two-Stage Finishing

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In magnetorheological finishing of 6063 aluminum alloy, as the current increases, both the improvement in surface roughness and the material removal are enhanced; however, excessively high currents raise the temperature in the finishing area, affecting the quality of the polished surface;

- (2)

- The vibration frequency of the magnetic clusters increases with the current frequency. At a current frequency of 1 Hz, the circulation and renewal of abrasives in the magnetic cluster are most sufficient, and it does not create excessive impact forces on the workpiece surface, resulting in the best finishing effect;

- (3)

- As the excitation gap increases from 1.5 mm to 2.5 mm, both the improvement in surface roughness and the material removal rate gradually decrease. An excitation gap smaller than 1 mm can interfere with the vertical movement of the magnetic clusters, to some extent hindering the renewal of abrasives and thus reducing finishing efficiency;

- (4)

- Larger iron powder particle sizes form longer magnetic clusters, which increase the material removal. At an iron powder particle size of 1 μm, the magnetic cluster response time is shortest, and the variation is greatest, achieving the best surface roughness value;

- (5)

- Using a low-frequency alternating magnetic field magnetorheological finishing method to polish 6063 aluminum alloy for 80 min reduced the initial surface roughness from 285 nm to 3.54 nm, achieving ultra-precision finishing of 6063 aluminum alloy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, W.Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.L. Effect of Anodizing Treatment on Ultrasonic Welding 6063 Aluminum Alloy and PPS. Rare. Metal. Mat. Eng. 2022, 51, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.W.; Li, Y.X. Microstructure and Compressive Properties of Aluminum Foams Made by 6063 Aluminum Alloy and Pure Aluminum. Mater. Trans. 2018, 59, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, D.; Rao, P. Corrosion behaviour of 6063 aluminium alloy in acidic and in alkaline media. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 2234–2244. [Google Scholar]

- Dilrukshi, L.W.U.R.; De Silva, G.I.P. Effect of precipitate size distribution on hardness of aluminium 6063 alloy. J. Natl. Sci. Found. Sri. 2020, 48, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouliprasanth, B.; Hariharan, P. An Experimental Study and Analysis of Different Dielectrics in Electrical Discharge Machining of Al 6063 Alloy. J. Polym. Mater. 2019, 36, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.W.; Chung, Y.Z.; Teo, G.S.; Kok, C.K. Effect of Tool Pin Geometry on the Microhardness and Surface Roughness of Friction Stir Processed Recycled AA 6063. Metals 2021, 11, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syryamkin, R.S.; Gorbunov, Y.A.; Otmahova, A.Y. Investigation into the Influence of the Degree of Grinding of the Ingot Grain Structure of the 6063 Alloy on Its Plasticity, Extruding Parameters, and Properties of Extruded Profiles. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2019, 60, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.X.; Shen, C.; Xu, H.; Li, G.H.; Xue, J.; Tan, G.Y. Experiment research on cavitation in high-speed milling with internal cooling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Fang, F.Z.; Deng, H. A generic approach of polishing metals via isotropic electrochemical etching. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manu. 2020, 150, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, S.; Niranjan, M.S.; Singh, V. To study the effect of different reinforcements on various parameters in aluminium matrix composite during CNC turning. Compos. Commun. 2021, 22, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, M.; Moetakef-Imani, B. Adaptive inverse control of chatter vibrations in internal turning operations. Mech. Syst. Signal. Pract. 2019, 129, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Afzal, B.; Huang, Z.L.; Yang, M.J.; Sun, S.S. Study on new magnetorheological chemical polishing process for GaN crystals: Polishing solution composition, process parameters, and roughness prediction model. Smart. Mater. Struct. 2023, 32, 035031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Mishra, V.; Sharma, R.; Iqbal, F.; Ali, S.W.; Kumar, S.; Khan, G.S. Development of magnetic nanoparticle based nanoabrasives for magnetorheological finishing process and all their variants. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 6254–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.S.; Chen, Z.J.; Yan, Q.S. Study on the rheological properties and polishing properties of SiO2@CI composite particle for sapphire wafer Smart. Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 114003. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, A.S.; Das, M.; Kapil, S. A Hybrid Electrochemical Magnetorheological Finishing Process for Surface Enhancement of Biomedical Implants. J. Manuf. Sci. E-Tasme 2024, 146, 051004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yao, L.; Guo, J.; Kang, S.; Mao, W.; Zuo, D. Experimental Investigation on Magnetic Abrasive Finishing for Internal Surfaces of Waveguides Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2024, 17, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Prakash, C.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Shabadi, R.; Królczyk, G.; Chudy, M.B.; Babbar, A. Magneto-Rheological Fluid Assisted Abrasive Nanofinishing of β-Phase Ti-Nb-Ta-Zr Alloy: Parametric Appraisal and Corrosion Analysis. Materials 2020, 13, 5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Lu, M.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Li, W. Improved magnetorheological finishing process with arc magnet for borosilicate glass. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2022, 37, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, R.; Moucka, R.; Sedlacik, M.; Pata, V. Iron-Sepiolite High-Performance Magnetorheological Polishing Fluid with Reduced Sedimentation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Yin, S.H.; Xing, B.J.; Zou, Y.H. Effect of magnetic pole on finishing characteristics in low-frequency alternating magnetic field for micro-groove surface. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2019, 104, 4745–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Zou, Y.; Sugiyama, H. Study on finishing characteristics of magnetic abrasive finishing process using low-frequency alternating magnetic field. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, G.; Sidpara, A.; Bandyopadhyay, P.P. Experimental and theoretical investigation into surface roughness and residual stress in magnetorheological finishing of OFHC copper. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 288, 116899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.A.; Jha, S. Selection of optimum polishing fluid composition for ball end magnetorheological finishing (BEMRF) of copper. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 100, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Singh, S.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Królczyk, G.; Bogdan-Chudy, M.; Wu, Y.L.; Zheng, H.Y. Experimental investigation into nano-finishing of β-TNTZ alloy using magnetorheological fluid magnetic abrasive finishing process for orthopedic applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Wu, J.Z.; Quang, N.M.; Duc, L.A.; Son, P.X. Applying fuzzy grey relationship analysis and Taguchi method in polishing surfaces of magnetic materials by using magnetorheological fluid. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2021, 112, 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, M.; Mangal, S.K. Development of continuous flow magnetorheological fluid finishing process for finishing of small holes. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. 2019, 41, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, A.Y.; Quan, H.J.; Li, Z.Z.; Zou, Y.H. Study on plane magnetic abrasive finishing process (characteristics of finished surface). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 80, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Xie, H.; Dong, C.; Wu, J. Study on complex micro surface finishing of alumina ceramic by the magnetic abrasive finishing process using alternating magnetic field. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Jain, V.K.; Raghuram, V. Experimental investigations into forces acting during a magnetic abrasive finishing process. Int. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2006, 30, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulik, R.S.; Pandey, P.M. Ultrasonic assisted magnetic abrasive finishing of hardened AISI 52100 steel using unbonded SiC abrasives. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2011, 29, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulik, R.S.; Pandey, P.M. Mechanism of surface finishing in ultrasonic-assisted magnetic abrasive finishing process. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2010, 25, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zou, Y.; Sugiyama, H. Study on ultra-precision magnetic abrasive finishing process using low frequency alternating magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 386, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Yin, S.H.; Yang, S.J.; Guo, Y.F. Study on magnetorheological nano-polishing using low-frequency alternating magnetic field. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 1687814019900721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | 1st Experiment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 | |

| Finishing time (min) | 120 | |||

| Grinding fluid (mL) | Oil-based cutting fluid | |||

| Abrasive | Diamond, (mean dia): 1 μm | |||

| Tray rotation speed (rpm) | 30 | |||

| Workpiece rotation speed (rpm) | 600 | |||

| Average alternating current (A) | 2/4/6/8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Carbonyl iron powder (μm) | 3 | 1/3/6/9 | 3 | 3 |

| Excitation gap (mm) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1/1.5/2/2.5 | 1.5 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1/3/5/7 |

| Parameters | First Stage | Second Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Finishing time (min) | 40 | 40 |

| Average alternating current (A) | 4 | 4 |

| Carbonyl iron powder (μm) | 6 | 1 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 7 | 1 |

| Excitation gap (mm) | 1.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Y.; Wu, J. Influence of Excitation Parameters on Finishing Characteristics in Magnetorheological Finishing for 6063 Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 2670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112670

Fang Y, Wu J. Influence of Excitation Parameters on Finishing Characteristics in Magnetorheological Finishing for 6063 Aluminum Alloy. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112670

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Yiming, and Jinzhong Wu. 2024. "Influence of Excitation Parameters on Finishing Characteristics in Magnetorheological Finishing for 6063 Aluminum Alloy" Materials 17, no. 11: 2670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112670

APA StyleFang, Y., & Wu, J. (2024). Influence of Excitation Parameters on Finishing Characteristics in Magnetorheological Finishing for 6063 Aluminum Alloy. Materials, 17(11), 2670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112670