Kinetics of Martensite/Austenite Decomposition during Tempering of Ultrafine Nano-Bainitic Steels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

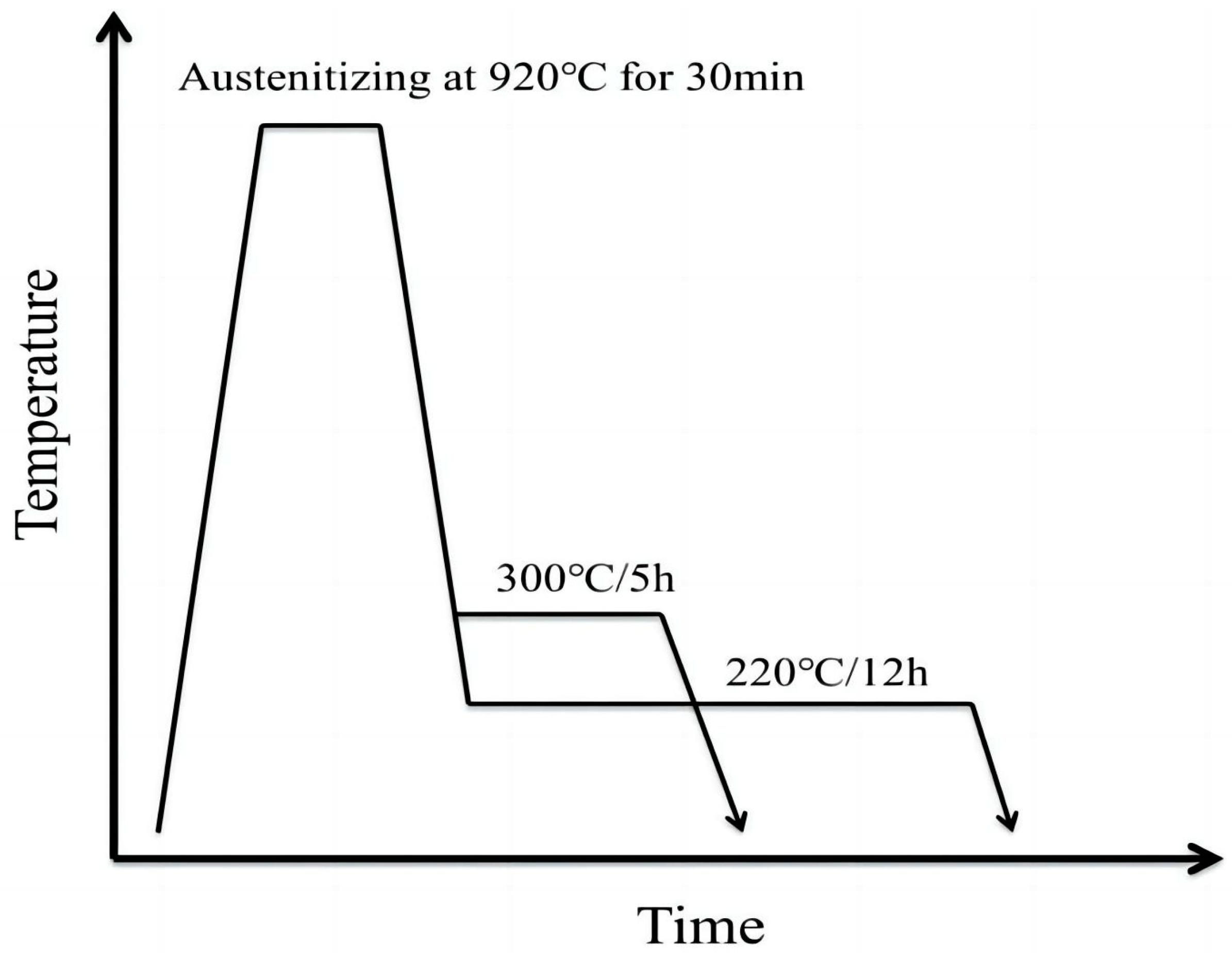

2. Experimental Materials and Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

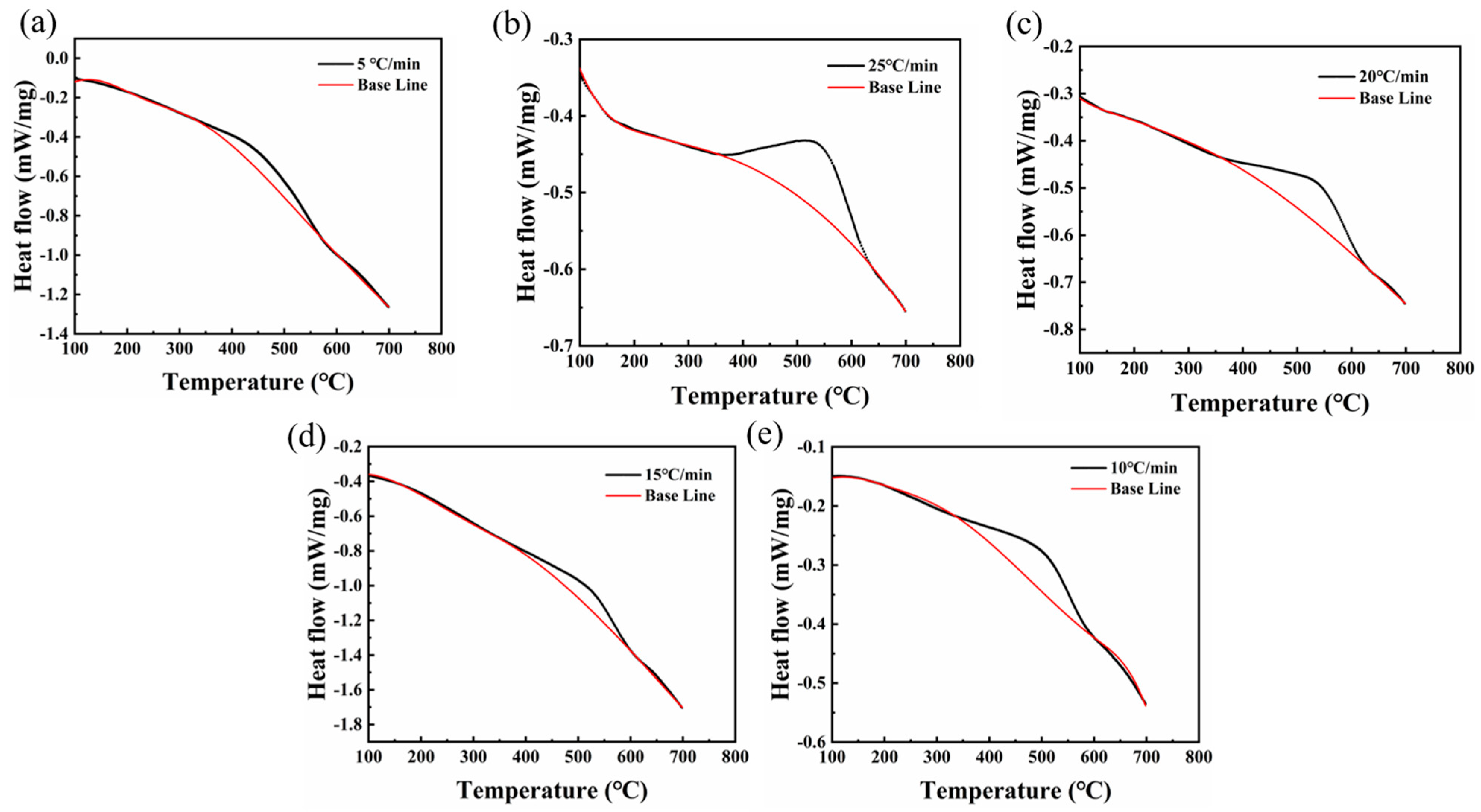

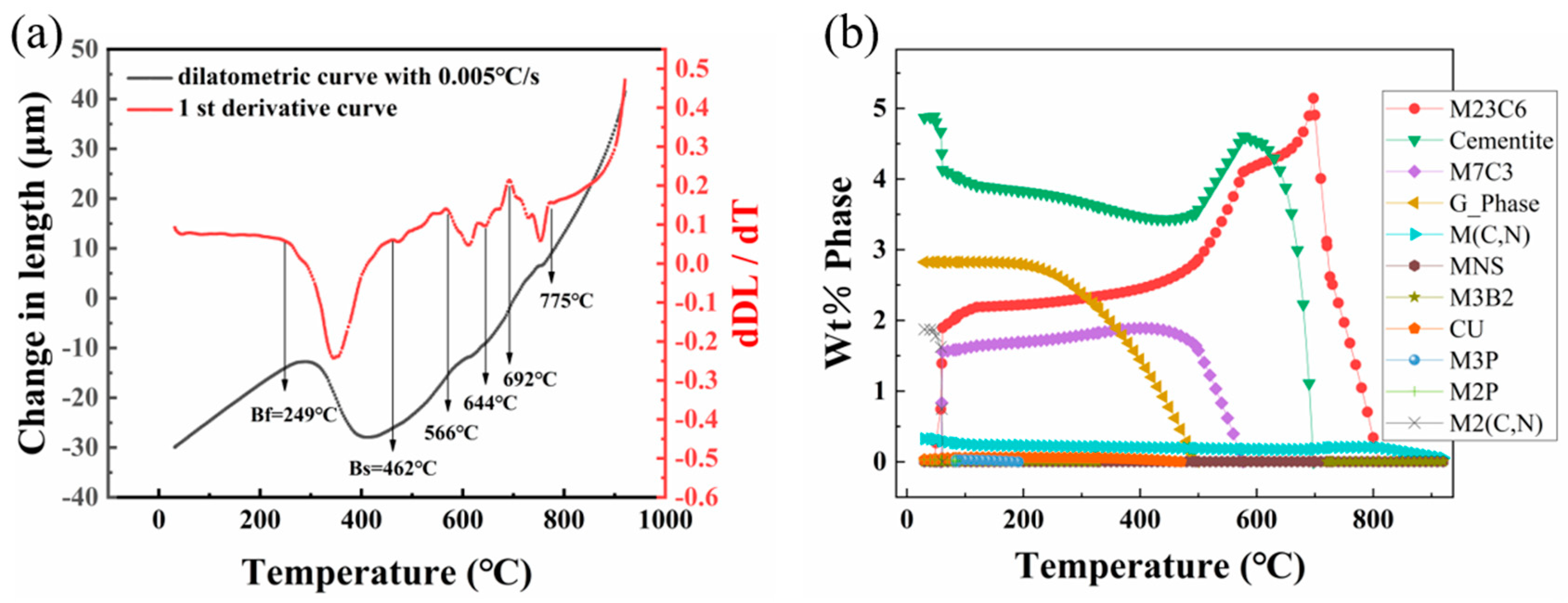

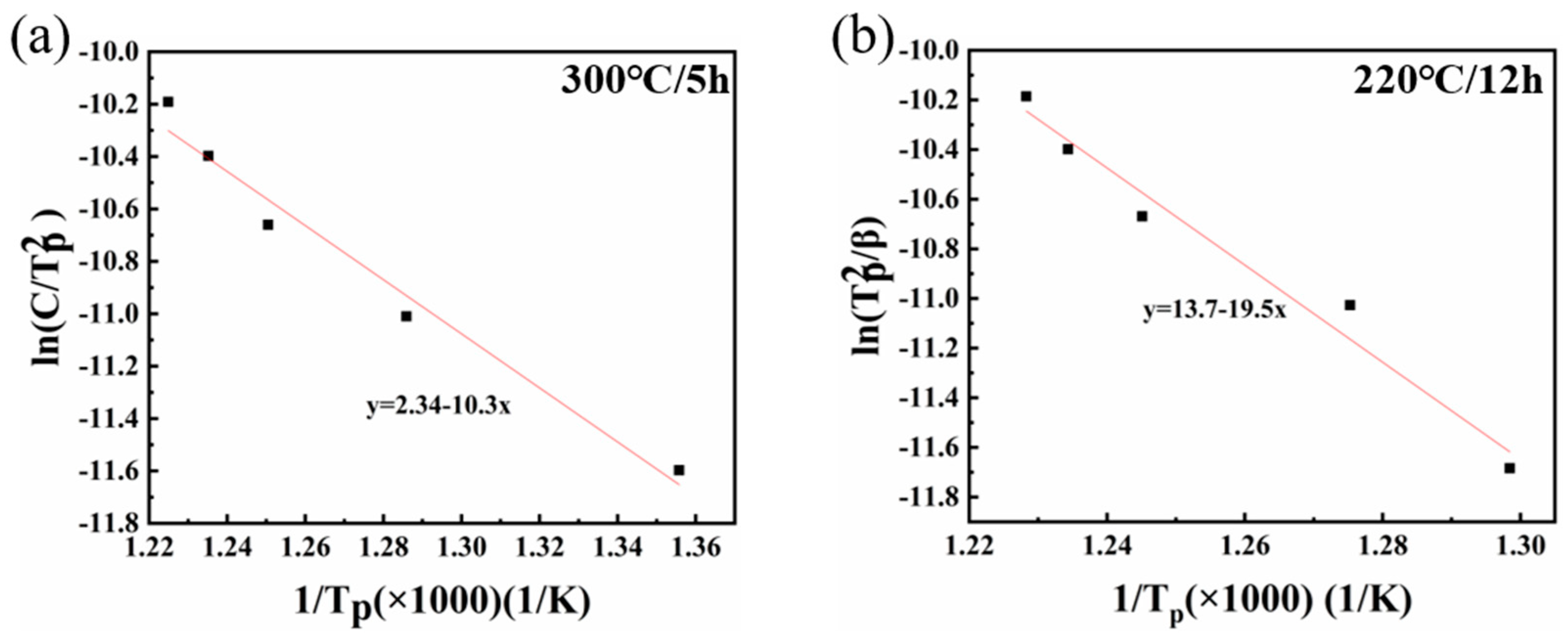

3.1. Kinetic Equation of M/A Decomposition

3.2. Experimental Validation of the Proposed Kinetic Equation and Decomposition of M/A

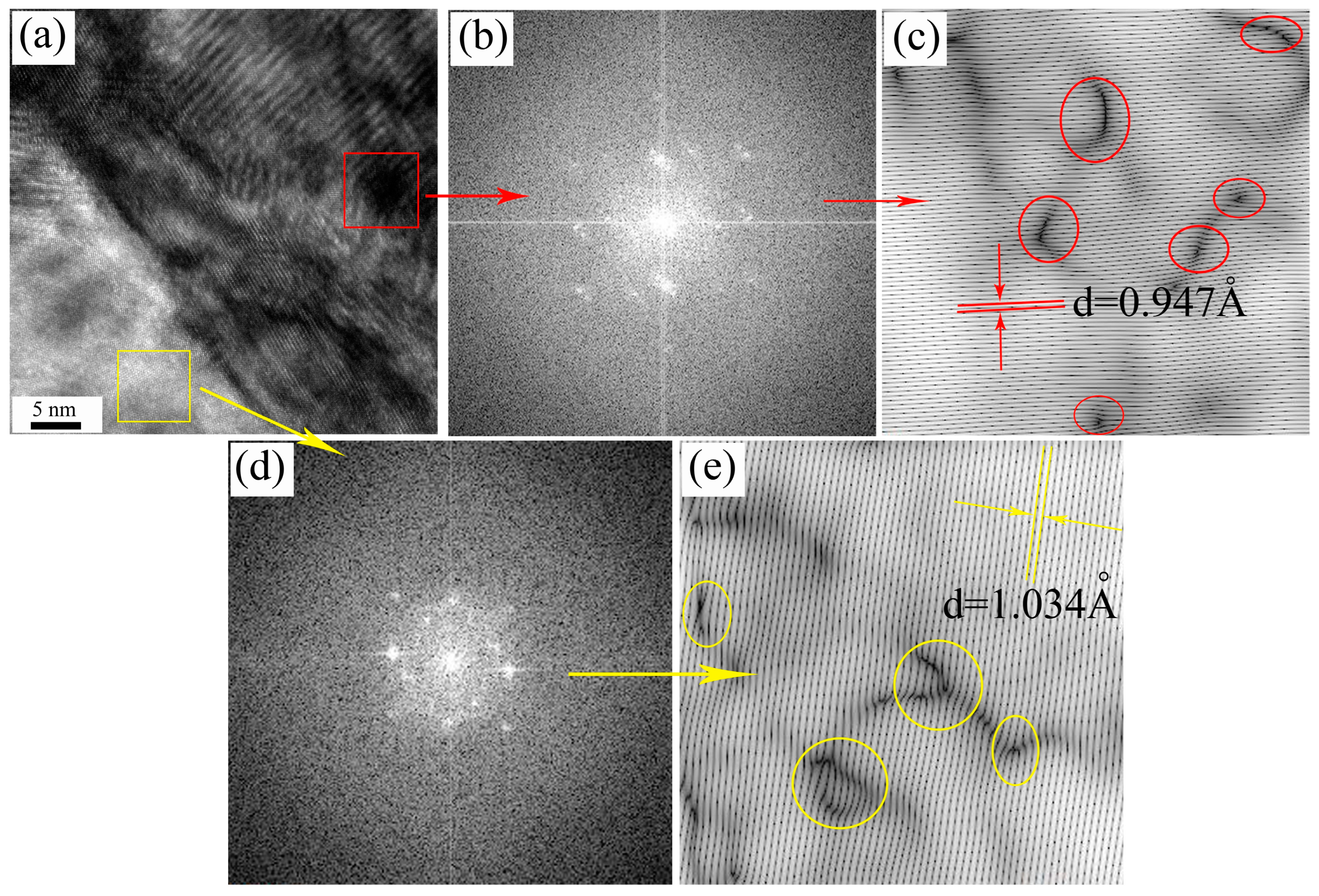

3.2.1. Analysis of the Microstructure Prior to Tempering

3.2.2. Impact of Tempering on the Microstructure

4. Conclusions

- Each sample demonstrated exothermic peaks proximate to 600 °C at varying heating rates. Notably, the 220 °C/12 h sample exhibited two such peaks, one near 300 °C and another around 600 °C. The precipitation activation energies for these exothermic peaks at 600 °C in the 300 °C/5 h and 220 °C/12 h samples were 85.8 kJ/mol and 161.12 kJ/mol, respectively.

- The kinetic equation was derived from the DSC data, and its computation indicated that the carbide precipitation completion time was approximately 67 min at 600 °C.

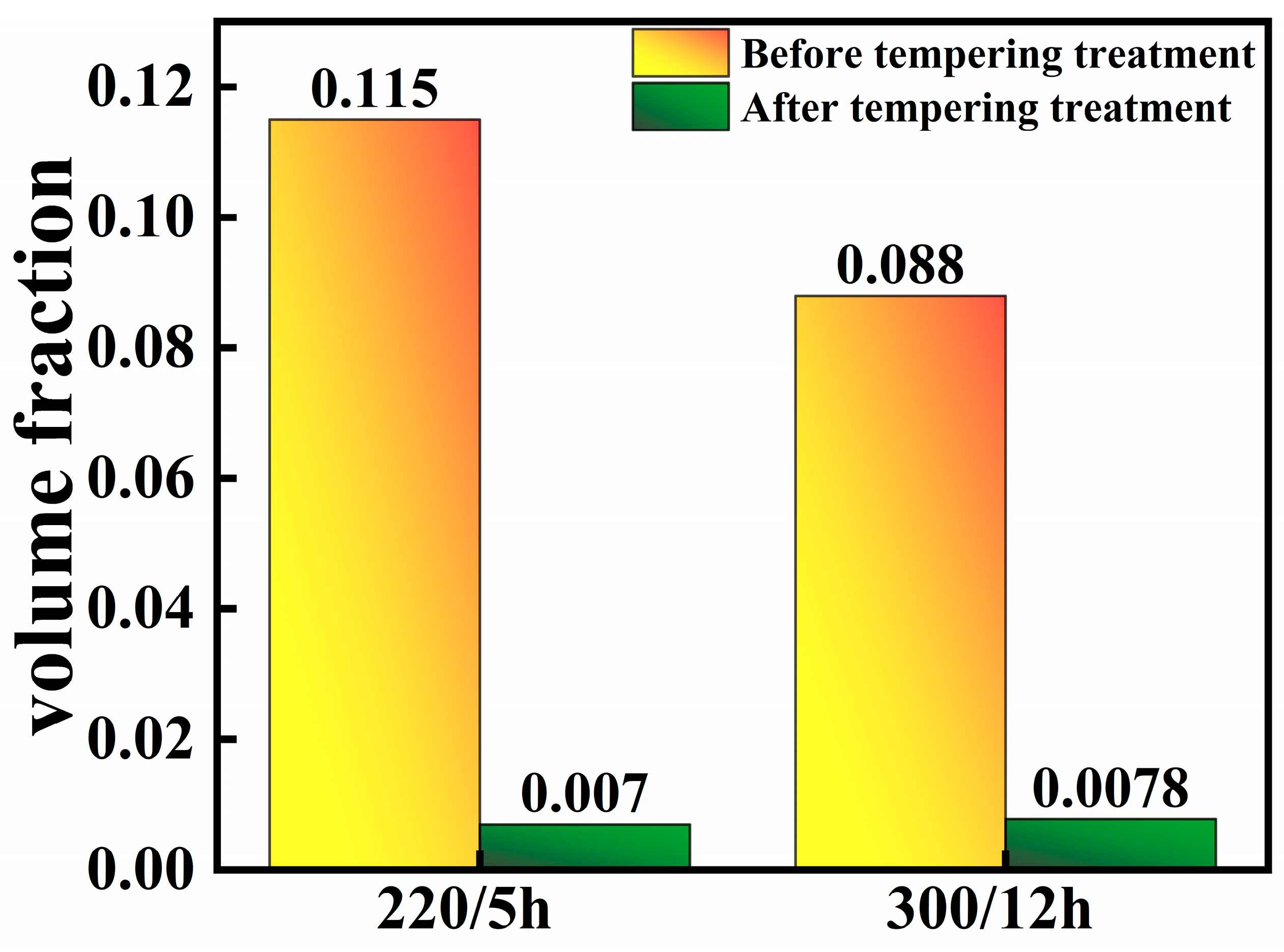

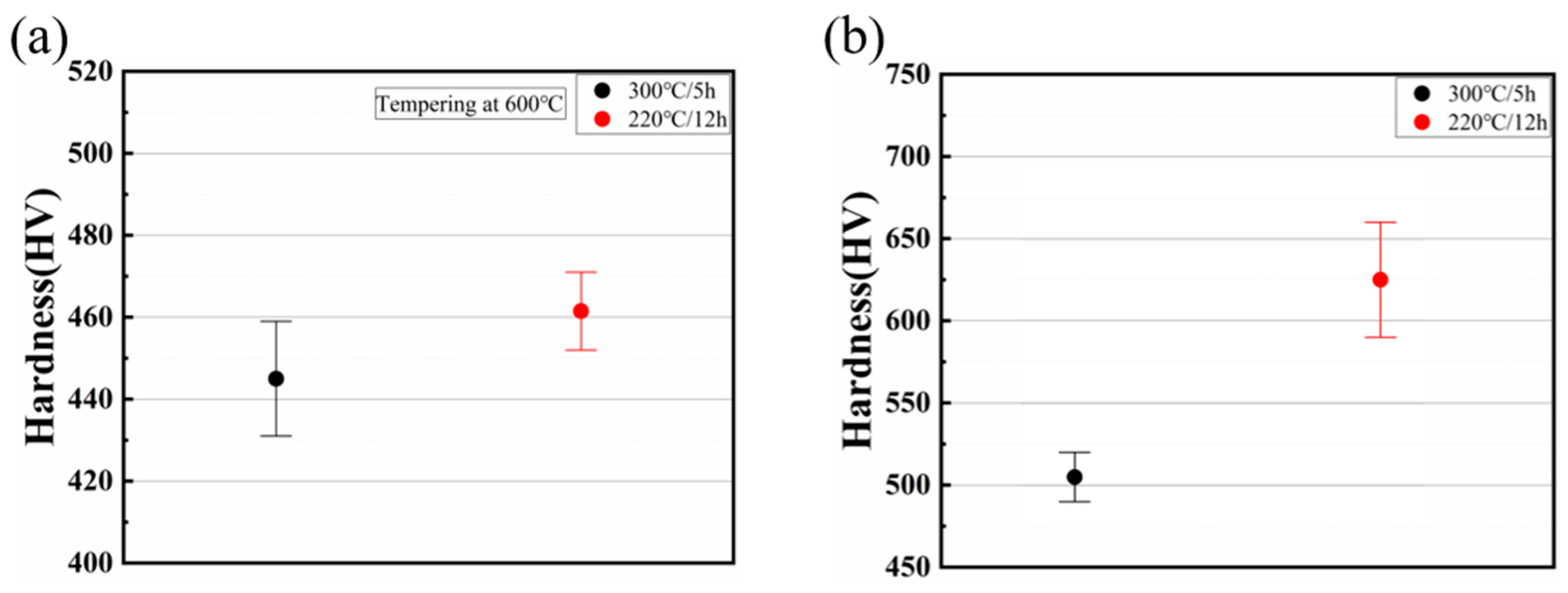

- To confirm this outcome, the specimen underwent a tempering process at 600 °C for a duration of 67 min. A subsequent microscopic examination revealed a significant decomposition of the M/A structure, indicating a residual volume fraction at less than 1%. Additionally, the sample’s hardness decreased to approximately 450 HV, a consequence of the M/A decomposition post-tempering.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, J.; Xu, G.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhou, M. Effect of Ni Addition on Bainite Transformation and Properties in a 2000 MPa Grade Ultrahigh Strength Bainitic Steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2018, 24, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tian, J.; Xu, G.; Zurob, H.S. New insights into the effects of deformation below-MS on isothermal kinetics of bainitic transformation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Liu, S.; Tu, Y.; Yang, S.; Gao, K.; Yang, X.; Pang, X. Enhancing the hydrogen embrittlement resistance with cementite/VC multiple precipitates in high-strength steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 874, 145084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L. Comparison of microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties of the high-strength low-alloy steels fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing versus conventional casting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 885, 145593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Z.; Wu, G.; Mao, X. Titanium microalloying of steel: A review of its effects on processing, microstructure and mechanical properties. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, T.; Gong, N.; Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.Z.; Murr, L.E. Additive manufacturing of ultra-high strength steels: A review. J. Alloy Compd. 2023, 965, 171390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishan, B.; Sefidgar, A.; Yazdani, S. High strain rate deformation of nanostructured super bainite. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, S.; Avishan, B.; Yazdani, S. Effect of 10% ausforming on impact toughness of nano bainite austempered at 300 °C. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 656, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, X.; Huang, W. Improved Mechanical Properties of a Quenched and Partitioned Medium-Carbon Bainitic Steel by Control of Bainitic Isothermal Transformation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashangeh, S.; Karimi Zarchi, H.R.; Ghasemi Banadkouki, S.S.; Somani, M.C. Detection and Estimation of Retained Austenite in a High Strength Si-Bearing Bainite-Martensite-Retained Austenite Micro-Composite Steel after Quenching and Bainitic Holding (Q&B). Metals 2019, 9, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashangeh, S.; Somani, M.C.; Ghasemi Banadkouki, S.S.; Karimi Zarchi, H.R.; Kaikkonen, P.; Porter, D.A. On the decomposition of austenite in a high-silicon medium-carbon steel during quenching and isothermal holding above and below the Ms temperature. Mater. Charact. 2020, 162, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, J.; Seo, E.J.; Cho, L. Correlation between mechanical stability and hardness of austenite in martensite/austenite mixtures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 822, 141687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Ma, X.; Subramanian, S.V.; Shang, C. Influence of Martensite–Austenite constituents formed at different intercritical temperatures on toughness. Mater. Des. 2015, 67, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A.; Sangal, S.; Pramanick, A.K.; Mondal, K. On the extent of transformation of austenite to bainitic ferrite and carbide during austempering of high Si steel for prolonged duration and its effect on mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 793, 139764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, F.G.; Garcia-Mateo, C.; Miller, M.K. Design of Novel Bainitic Steels: Moving from UltraFine to Nanoscale Structures. JOM 2014, 66, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Lei, Z.; Wang, D.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Low-temperature impact toughness of laser–arc hybrid welded low-carbon bainitic steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 12775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Qian, L.; Meng, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, F. Below-Ms austempering to obtain refined bainitic structure and enhanced mechanical properties in low-C high-Si/Al steels. Scr. Mater. 2016, 112, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Frankenbach, T.; Wettlaufer, M. Strengthening 42CrMo4 steel by isothermal transformation below martensite start temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 683, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 18Mn3Si2CrMo steel subjected to austempering at different temperatures below Ms. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 724, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, N.; Ding, Y.; Gerlich, A.P. Temper-treatment development to decompose detrimental martensite-austenite and its effect on linepipe welds. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2017, 33, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santajuana, M.A.; Rementeria, R.; Kuntz, M.; Jimenez, J.A.; Caballero, F.G.; Garcia-Mateo, C. Low-Temperature Bainite: A Thermal Stability Study. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, M.; Mirzadeh, H.; Malekan, M. Precipitation kinetics of γ″ phase and its mechanism in a Nb-bearing nickel-based superalloy during aging. Vacuum 2020, 178, 109456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, B.; Frisk, K.; Nyborg, L. Effect of precipitation kinetics on microstructure and properties of novel Al-Mn-Cr-Zr based alloys developed for powder bed fusion—Laser beam process. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 920, 165870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemifar, S.; Mirzadeh, H. Precipitation kinetics of gamma double prime phase during direct aging treatment of inconel 718 superalloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 4248–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Shen, Y.F.; Jia, N.; Wang, J.J.; Xue, W.Y. Dynamic recrystallization and constitutive equation of 15Cr-10Mn-Ni-N steel under hot deformation. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Tong, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, B. Effects of aging process on properties and precipitation kinetics of Cu–Cr–Zr alloy strips. Trans. Nonferrous Metal. Soc. 2023, 33, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoljan, B.; Iljkić, D.; Smokvina Hanza, S.; Hajdek, K. Mathematical Modelling of Isothermal Decomposition of Austenite in Steel. Metals 2021, 11, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, D.; Xu, J.; Jiang, S.; Ning, X.; Liu, J.; Shang, S. Crystallization temperature investigation of Cu2ZnSnS4 by using Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 4256. [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, R.; Maqueda, L.P.; Podzemná, V.; Perejon, A.; Svoboda, O. Influence of DSC thermal lag on evaluation of crystallization kinetics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 528, 119738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, J.J.; Pérez-Orozco, R.; Patiño Vilas, D.; Porteiro, J. TG/DSC and kinetic parametrization of the combustion of agricultural and forestry residues. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 162, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. Nonisothermal Crystallization Kinetics by DSC: Practical Overview. Processes 2023, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lei, Y.; Yu, P.; Li, C.; Yao, B.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Peng, H. Novel high-precision wax molecular diffusion coefficient correlation based on the diffusion laboratory apparatus coupled with differential scanning calorimeter. Fuel 2024, 355, 129452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzajani, V.; Nazarpour-Fard, H.; Farhadi, K. Impacts of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on thermal decomposition kinetics of nitrocellulose-based propellant as a bio-derived polymer. Iran. Polym. J. 2024, 33, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Lei, M.; Wan, M.; Huang, C. Effect of pre-formed martensite quenching plus inverted multi-step heat treatment on medium-carbon alloy steel. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2023, 23, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Mi, G. Influence of Alloying Elements Content on High Temperature Properties of Ti-V-Cr and Ti-Al-V Series Titanium Alloys: A JMatPro Program Calculation Study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2639, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.; Uhm, S.; Lee, C. Kinetics Study on Low-Temperature Tempering of Martensitic Phase in Medium Mn Steel Weldment During Paint-Baking Heat Treatment. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, R.L.; Kissinger, H.E. Homer Kissinger and the Kissinger equation. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 540, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajra, R.N.; Dash, M.K.; Chu, W.; Singh, A.N.; Nam, K.; Kim, J.H. High-temperature phase stability, γ → δ transformation of ferritic/martensitic steel studied by differential scanning calorimetry and electron backscatter diffraction. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Feng, X.; Zhao, A.; Li, Q.; Chai, M. Effects of ausforming temperature on bainite transformation kinetics, microstructures and mechanical properties in ultra-fine bainitic steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, H.; Manabe, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Takahashi, M. Effect of Carbon Content on Bainite Transformation Start Temperature in Middle–High Carbon Fe–9Ni–C Alloys. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baricco, M.; Franzosi, G.; Nada, R.; Battezzati, L. Thermal effects due to tempering of austenite and martensite in austempered ductile irons. Mater. Sci. Tech. 1999, 15, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X.; Dong, C.; Kang, S. Effects of nucleation site and morphology of carbide-free bainite on microstructures and properties of bainite/martensite multi-phase steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 744, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindhart, A.; Blanton, T.; Blanton, J.; Gates-Rector, S. The Power of Electron Diffraction Phase Analysis and Pattern Simulations Using the ICDD ® Powder Diffraction File™ (PDF-4+). Microsc. Microanal. 2016, 22, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.D.; Miyamoto, G.; Yang, Z.G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Furuhara, T. Incomplete bainite transformation in Fe-Si-C alloys. Acta Mater. 2017, 133, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Miyamoto, G.; Yang, Z.G.; Zhang, C.; Furuhara, T. Direct measurement of carbon enrichment in the incomplete bainite transformation in Mo added low carbon steels. Acta Mater. 2015, 91, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, H.I.; Reynolds, W.T.; Purdy, G.R. The incomplete transformation phenomenon in steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2006, 37, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, H.; Bai, B. Very high cycle fatigue behaviors of bainite/martensite multiphase steel treated by quenching-partitioning-tempering process. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 92, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandiran, E.; Ueji, R.; Ogawa, Y.; Nagata, K.; Somekawa, H.; Demura, M. Deformation behaviour of novel medium carbon bainitic steels with different retained austenite characteristics designed by the sparse mixed regression model. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C.; Bliznuk, V.; Verdiere, A.; Petrov, R.; Winkelhofer, F.; Clemens, H.; Primig, S. High-resolution characterization of the martensite-austenite constituent in a carbide-free bainitic steel. Mater. Charact. 2018, 144, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Resiak, B.; Buessler, P.; Michaut, B.; Bleck, W. Effect of Molybdenum and Cooling Regime on Microstructural Heterogeneity in Bainitic Steel Wires. Steel Res. Int. 2020, 91, 1900663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.; Chiang, M.; Lin, Y.; Chen, D.; Huang, C.; Lin, H. High-Temperature Tempered Martensite Embrittlement in Quenched-and-Tempered Offshore Steels. Metals 2017, 7, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jimenez, V.; Kuntz, M.; Sourmail, T.; Caballero, F.G.; Jimenez, J.A.; Garcia-Mateo, C. Retained Austenite Destabilization during Tempering of Low-Temperature Bainite. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchón-Gordón, A.F.; Blázquez, J.S.; Conde, C.F.; Conde, A. Nanocrystallization kinetics understood as multiple microprocesses following the classical theory of crystallization. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 675, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogal, A.; Dutkiewicz, J. Effect of annealing on microstructure, phase composition and mechanical properties of thixo-cast 100Cr6 steel. Mater. Charact. 2012, 68, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | C | Si | Mn | Cr | Ni | Mo | V | Cu | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | 0.55 | 0.379 | 0.75 | 1.379 | 2.676 | 0.516 | 0.103 | 0.185 | Bal. |

| E (KJ/mol) | k0 | n | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 °C/min | 10 °C/min | 15 °C/min | 20 °C/min | 25 °C/min | ||||

| 300 | 85.8 | 1.07 × 102 | 1.26 | 1.31 | 1.47 | 1.42 | 1.39 | 1.37 |

| 220 | 162.12 | 1.7 × 107 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.77 |

| 300 | ) |

| 220 | ) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, Z.; Lei, M.; Chen, G.; Huang, C.; Liu, D.; Luo, A. Kinetics of Martensite/Austenite Decomposition during Tempering of Ultrafine Nano-Bainitic Steels. Materials 2024, 17, 2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112690

Qu Z, Lei M, Chen G, Huang C, Liu D, Luo A. Kinetics of Martensite/Austenite Decomposition during Tempering of Ultrafine Nano-Bainitic Steels. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112690

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Zhiwei, Min Lei, Guohua Chen, Chaowen Huang, Dan Liu, and Ai Luo. 2024. "Kinetics of Martensite/Austenite Decomposition during Tempering of Ultrafine Nano-Bainitic Steels" Materials 17, no. 11: 2690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112690