Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristic of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 2: Chemical Modification with Surface-Active Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

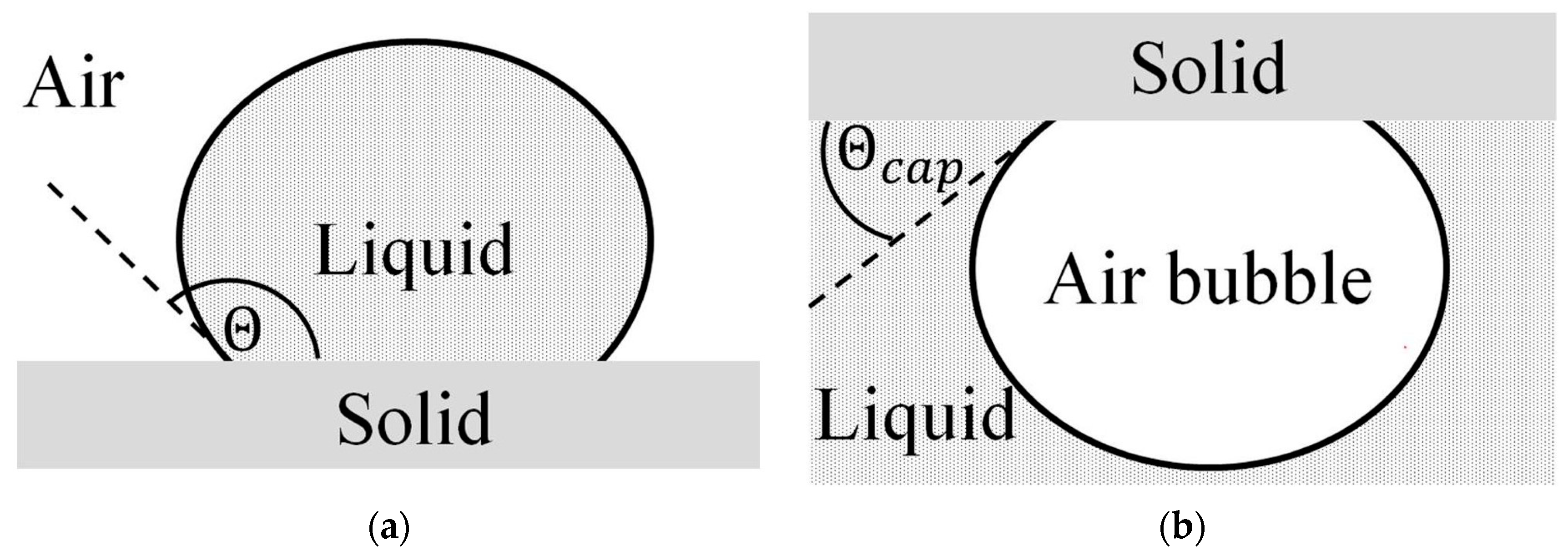

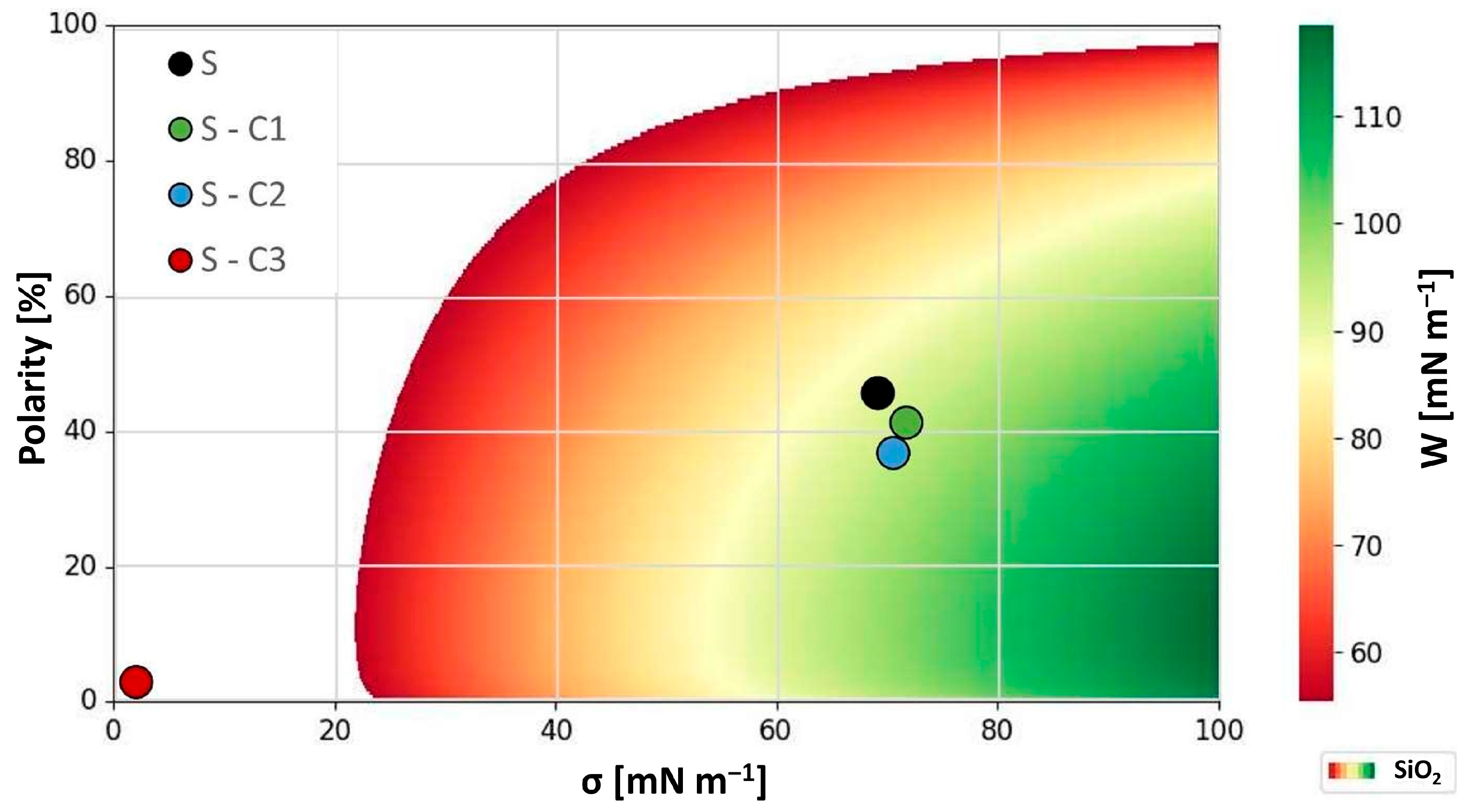

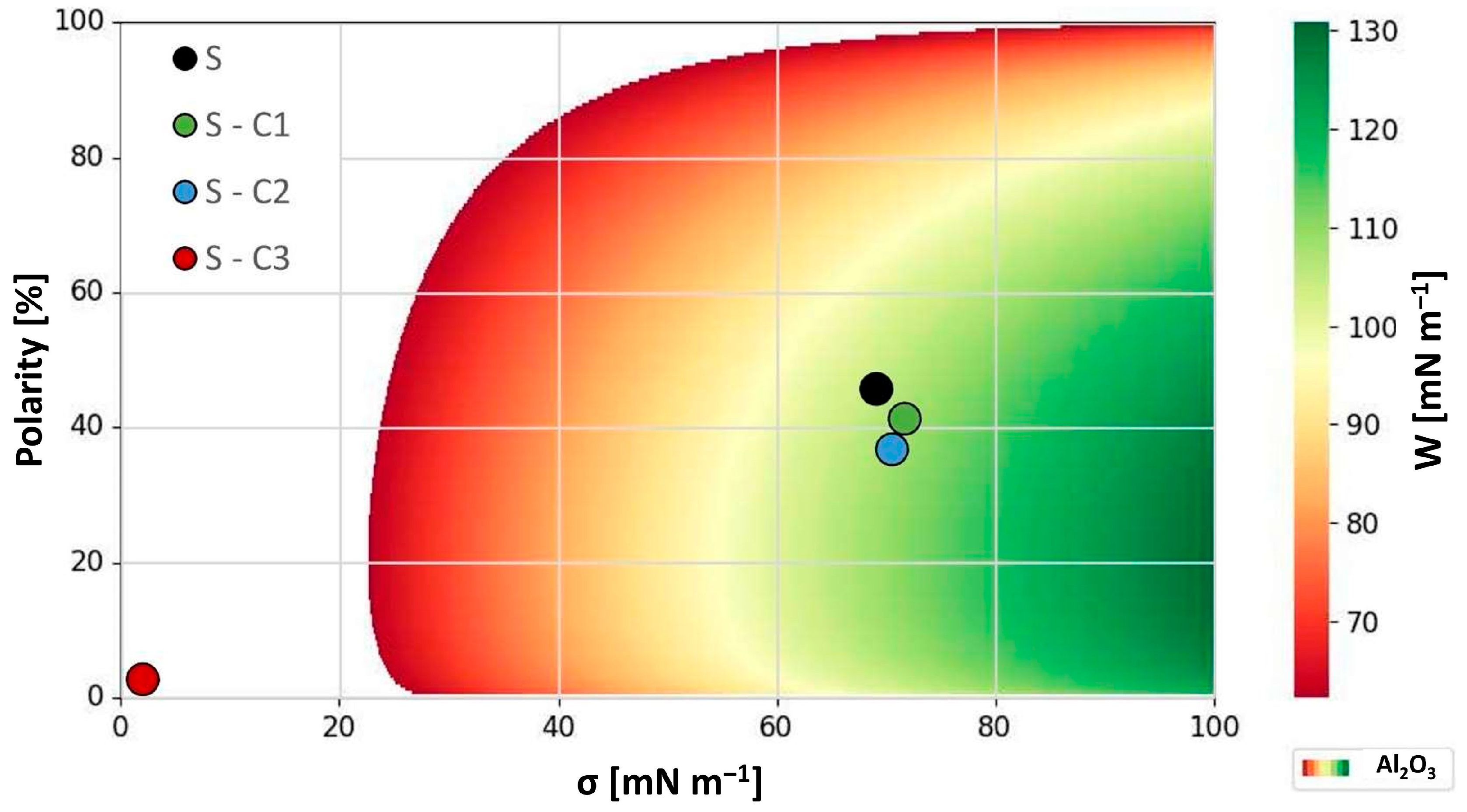

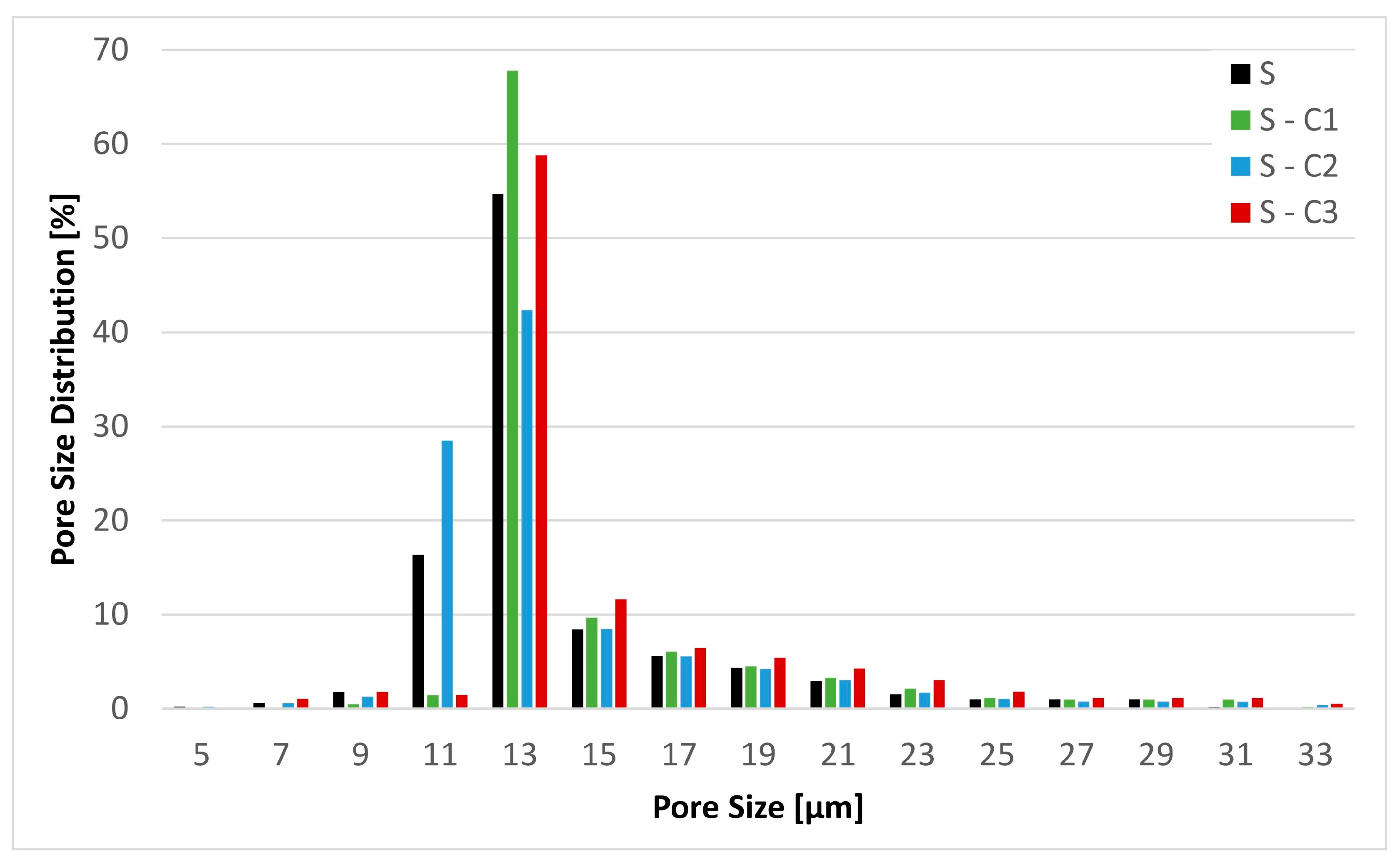

2.1. Textile Material Characterization Procedures

2.2. Evaluation of the Filtration Performance Characteristics

3. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakthivel, S.; Ezhil, A.J.; Ramachandran, T. Development of needle-punched nonwoven fabrics from reclaimed fibers for air filtration applications. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2014, 9, 155892501400900117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K.S.; Chase, G. Filters and Filtration Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-1-8561-7464-0. [Google Scholar]

- Visvanathan, C.; Aim, R.B. Water, Wastewater, and Sludge Filtration; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 0-8493-6983-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Shi, Y.; Qian, X. Characterization of glass fiber felt and its performance as an air filtration media. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51, 1186S–1206S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocchi, A.; Lachut, F.; Willis, W.H. Glass Fibers and Their Use as Filter Media. J. Air Pollut. Control. Assoc. 1962, 12, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Cox, C.L. Fibrous Filter Media; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; ISBN 0081005733. [Google Scholar]

- Lucica, C.; Ioan, C. Functional Design of the Woven Filters. In Advances in Modern Woven Fabrics Technology; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purchas, D.B.; Sutherland, K. (Eds.) Handbook of Filter Media; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; ISBN 1-85617-375-5. [Google Scholar]

- Duchowski, J.K.; Lang, T. Method for Adapting a Filter Medium to Predefinable and Preferably a Filter Medium Produced According to Said Methods. U.S. Patent 11,565,205 B2, 31 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt, J. Surface Energy Modification of Filter Media to Achieve Optimal Performance Characteristics in Select Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt, J.; Leyer, S.; Duchowski, J.K. Detailed characterization of the effect of application of commercially available surface treatment agents on textile wetting behavior. Coatings 2019, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, J.; Duchowski, J.K.; Leyer, S. Prevention of Electrostatic Charge Generation in Filtration of Low-Conductivity Oils by Surface Modification of Modern Filter Media. Tribol. Trans. 2020, 63, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiter, L.; Leyer, S.; Duchowski, J.K. Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristics of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 1: Mechanical Modification with Electrospun Nanofibers. Materials 2024, 17, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akduman, Cigdem. Nanofibers in Filtration. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335025947_NANOFIBERS_IN_FILTRATION (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Li, D.; Frey, M.W.; Joo, Y.L. Characterization of nanofibrous membranes with capillary flow porometry. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 286, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholdi, D.; Erlenmaier, I.; Seitz, A.; Maurer, C. Filter Media Performance and Ist Influence on Filtration Results—Experience, Expectations and Possibilities in Vacuum and Pressure Filtration. Available online: https://www.sefar.com/data/docs/fr/11894/FS-PDF-Filter-media-performance-02.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- DuPont de Nemours, I. Test Methods based on Methodologies from ASTM, ISO and Others. Available online: https://www.dupont.co.za/news/measuring-properties-of-tyvek.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Jena, A.; Gupta, K. Characterization of pore structure of filtration media. Fluid/Part. Sep. J. 2002, 14, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, A.; Gupta, K. Liquid extrusion techniques for pore structure evaluation of nonwovens. Int. Nonwovens J. 2003, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 5084:1996; Textiles–Determination of Thickness of Textiles and Textile Products. Standard AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 1996.

- DIN EN 12127:1997; Textilien—Textile Flächengebilde—Bestimmung der Flächenbezogenen Masse Unter Verwendung Kleiner Proben. German Institute for Standardisation: Berlin, Germay, 1997. Available online: https://www.dinmedia.de/de/norm/din-en-12127/3569979 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- DIN EN ISO 9237:1995; Textilien–Bestimmung der Luftdurchlässigkeit von textilen Flächengebilden. German Institute for Standardisation: Berlin, Germay, 1995.

- ASTM F316-03:2011; Standard Test Methods for Pore Size Characteristics of Membrane Filters by Bubble Point and Mean Flow Pore Test. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.astm.org/f0316-03r19.html (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Belgardt, C. Herstellung Mikrostrukturierter OTS-Monolagen auf Siliziumoxidoberflächen. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:ch1-qucosa-86379 (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Law, K.-Y. Definitions for hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, and superhydrophobicity: Getting the basics right. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rulison, C. Two-component surface energy characterization as a predictor of wettability and dispersability. KRUSS Appl. Note 2000, AN213, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, R.; Hiemenz, P.C. Principles of colloid and surface chemistry. Marcel Dekker 1997, 8247, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Young, T., III. An essay on the cohesion of fluids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1805, 95, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.M. Attractive forces at interfaces. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1964, 56, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Wendt, R.C. Estimation of the surface free energy of polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, C. Textile Werkstoffe Für Den Leichtbau; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelble, D.H. Dispersion-polar surface tension properties of organic solids. J. Adhes. 1970, 2, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prydatko, A.V.; Belyaeva, L.A.; Jiang, L.; Lima, L.M.C.; Schneider, G.F. Contact angle measurement of free-standing square-millimeter single-layer graphene. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzsche, J. Haftkräfte zwischen technisch rauen Oberflächen. Int. Nonwovens J. 2016, 9, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safety Data Sheet. Medium Test Dust. Available online: https://www.powdertechnologyinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/SDS.01.Arizona-Test-Dust.4-Feb-2016.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Loulidi, S.; Rogge, E.; Legein, F. Polymer Coatings and Methods for Depositing Polymer Coatings. U.S. Patent 11,419,220, 16 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dutschk, V. Oberflächenkräfte und ihr Beitrag zu Adhäsion und Haftung in Glasfaserverstärkten Thermoplasten. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 16889:2022; Hydraulic Fluid Power. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77245.html (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- ISO 3968:2017; Hydraulik—Filter—Bestimmung des Druckabfalles in Abhängigkeit von der Durchflusscharakteristik. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.dinmedia.de/de/norm/iso-3968/278003936 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Eleftherakis, J.G.; Khalil, A. Multipass Beta Filtration Testing for the 21st Century. Int. Nonwovens J. 2000, 3, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; von Arnim, V.; Stegmaier, T.; Planck, H. Effect of fibrous filter properties on the oil-in-water-emulsion separation and filtration performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, P.S.; Patel, S.U.; Chase, G.G. Layered hydrophilic/hydrophobic fiber media for water-in-oil coalescence. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 85, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Chase, G. The effect of wettability on drop attachment to glass rods. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 272, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical Properties | Method | Apparatus |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness | DIN EN ISO 5084:1996 [20] | Thickness gauge without pressure—Mitutoyo Deutschland GmbH, Neuss, Germany |

| Basis Weight | DIN EN 12127:1997 [21] | MSA225P-000-DA—Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany |

| Air Permeability | DIN EN ISO 9237:1995 [22] | FX3300—Textest AG, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland |

| Pore Size Distribution | ASTM F316-03:2011 [23] | Capillary Flow Porometer AX 1100—Porous Materials Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA |

| Material | σ [mN m−1] | σp [mN m−1] | σd [mN m−1] | Polarity [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 72.8 | 48.9 | 2.9 | 67.2 |

| CH2I2 | 51.2 | 0.1 | 51.1 | 0.2 |

| Material | σ [mN m−1] | σp [mN m−1] | σd [mN m−1] | Polarity [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIL-H-5606 [exp.] | 22.7 | 5.7 | 17.0 | 25.2 |

| SiO2 [exp.] | 35.1 | 3.8 | 31.3 | 10.7 |

| Al2O3 [34] | 42.8 | 8.7 | 34.1 | 20.3 |

| S | 69.0 | 31.6 | 37.4 | 45.8 |

| S-C1 | 71.6 | 29.6 | 42.0 | 41.4 |

| S-C2 | 70.5 | 26.0 | 44.5 | 36.8 |

| S-C3 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| Samples | Thickness [mm] | Basis Weight [g m−2] | Air Permeability [L m−2 s−1] | Min Pore [µm] | Max Pore [µm] | MFP [µm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 71.7 ± 1.7 | 230 ± 22 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 33.3 ± 0.1 | 12.8 ± 0.5 |

| S-C1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 68.6 ± 0.9 | 237 ± 4 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 32.3 ± 0.3 | 13.3 ± 0.1 |

| S-C2 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 78.6 ± 2.8 | 252 ± 5 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 32.7 ± 0.7 | 12.3 ± 0.4 |

| S-C3 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 82.9 ± 1.7 | 241 ± 8 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 33.0 ± 0.5 | 13.2 ± 0.3 |

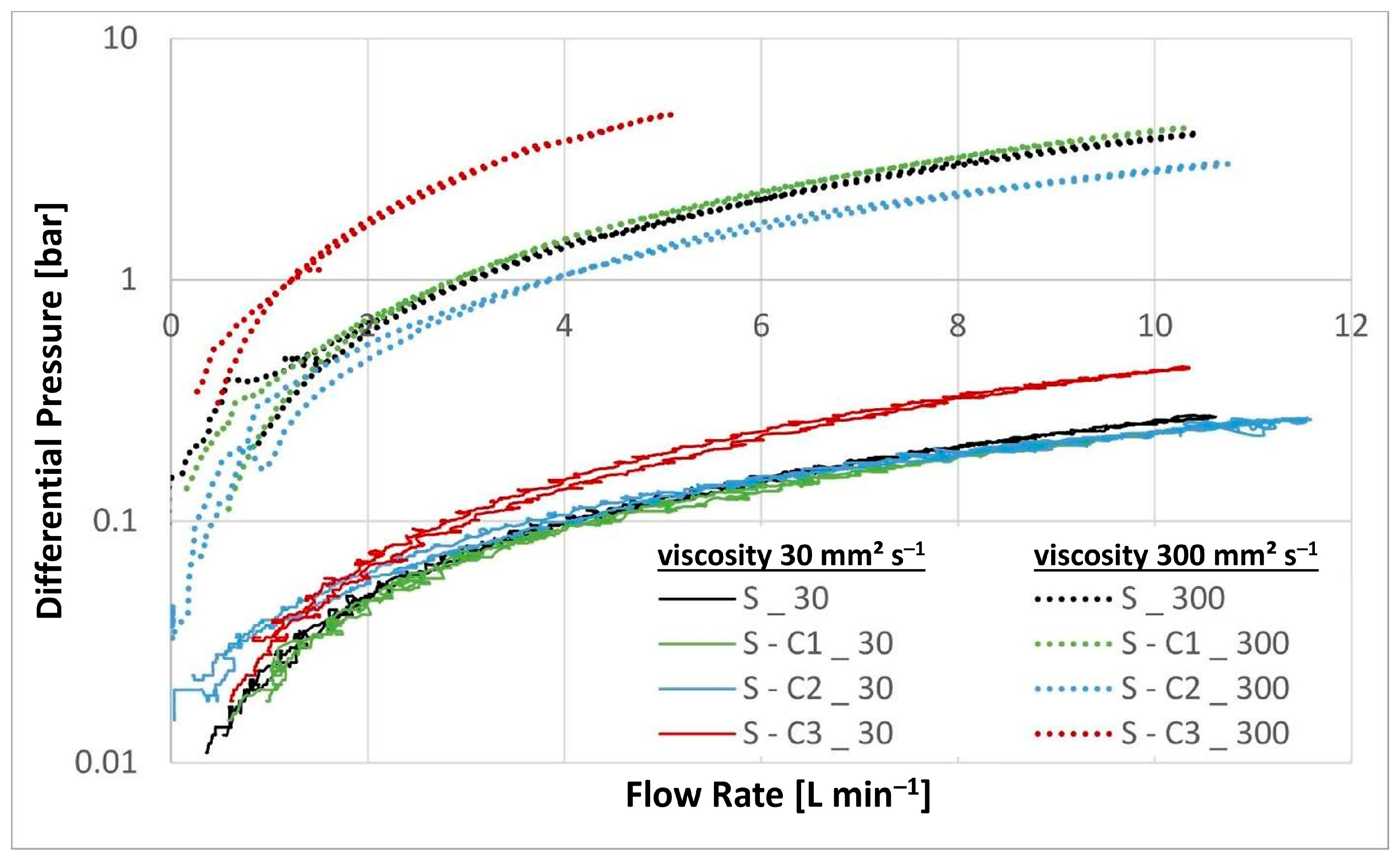

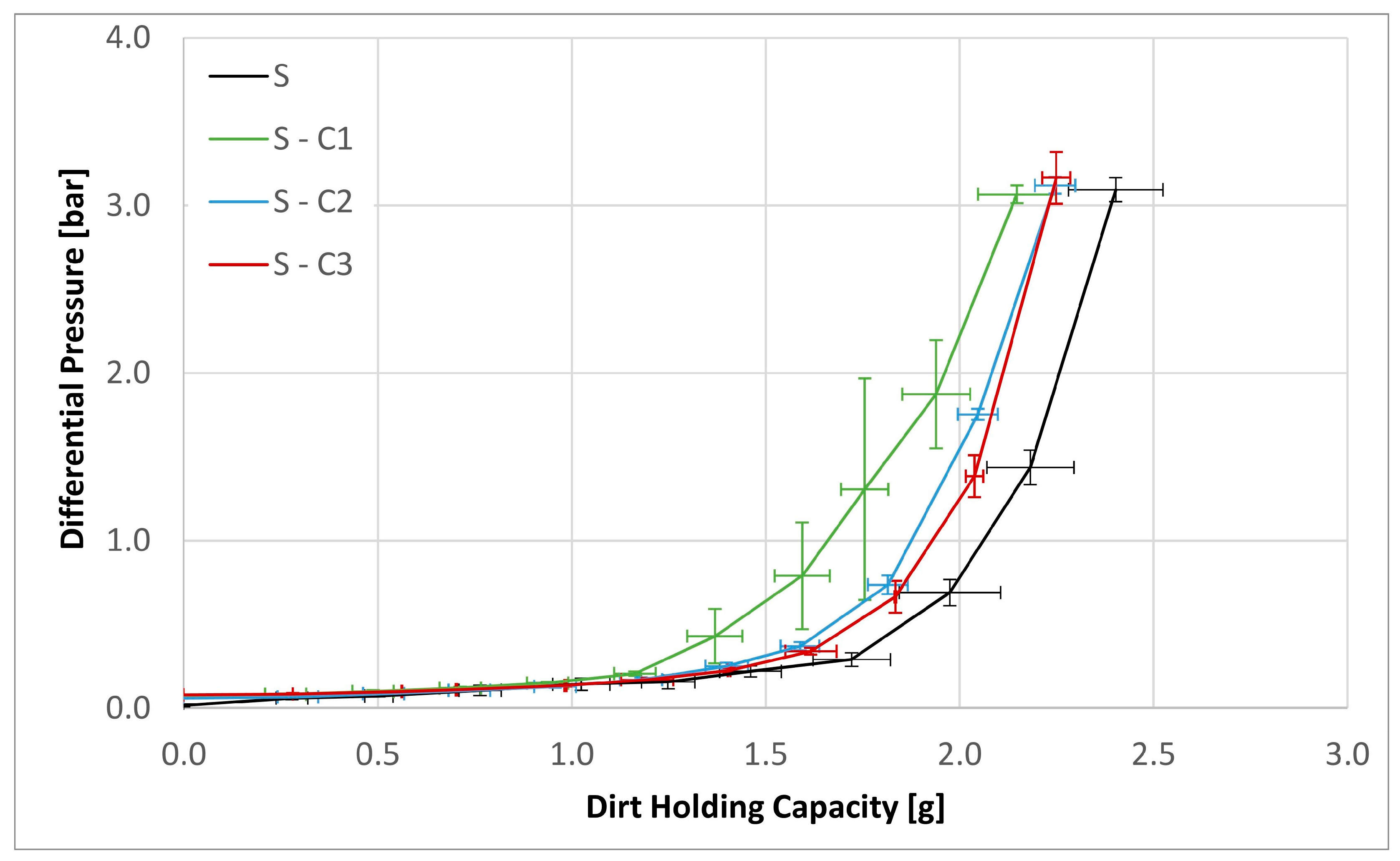

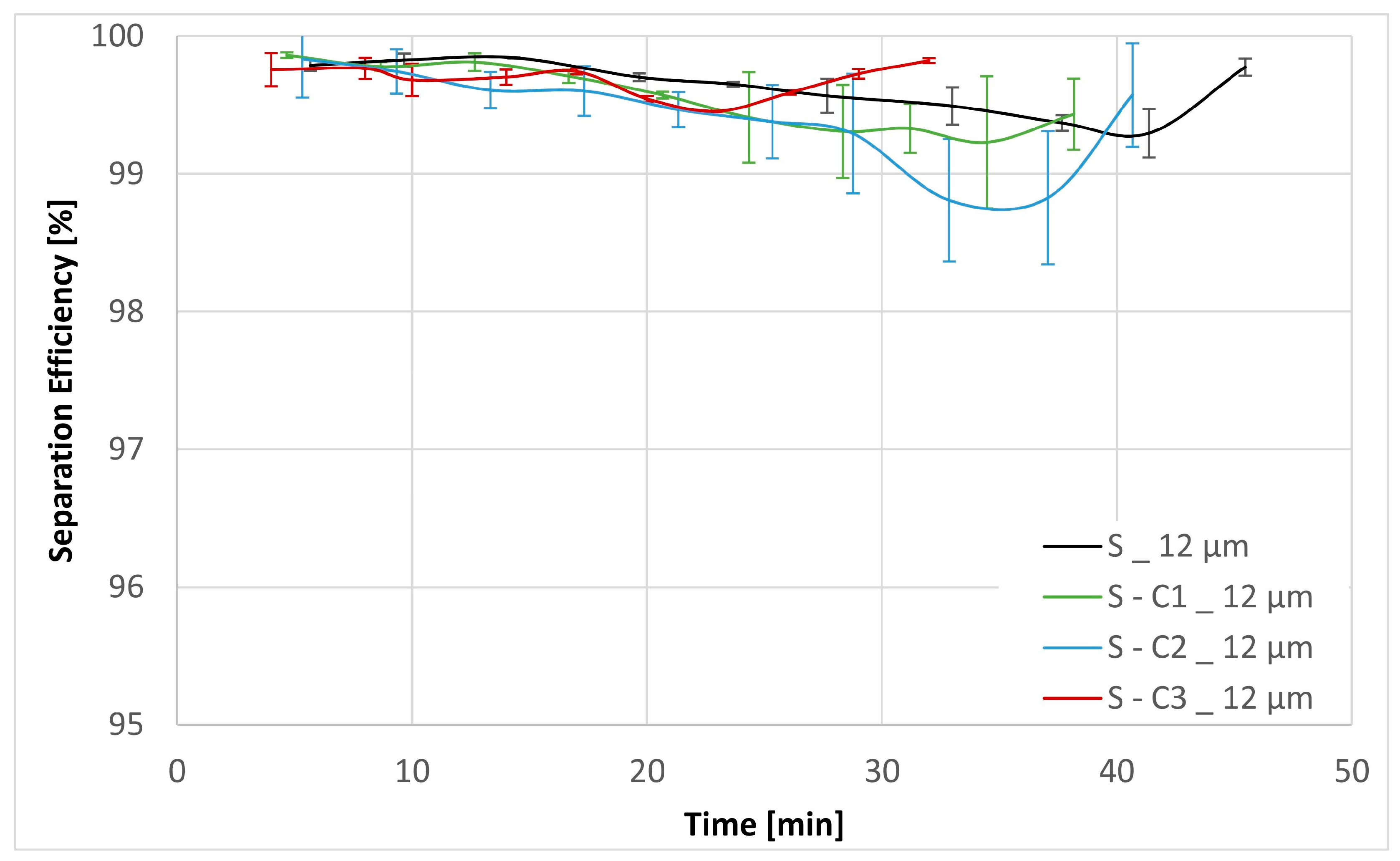

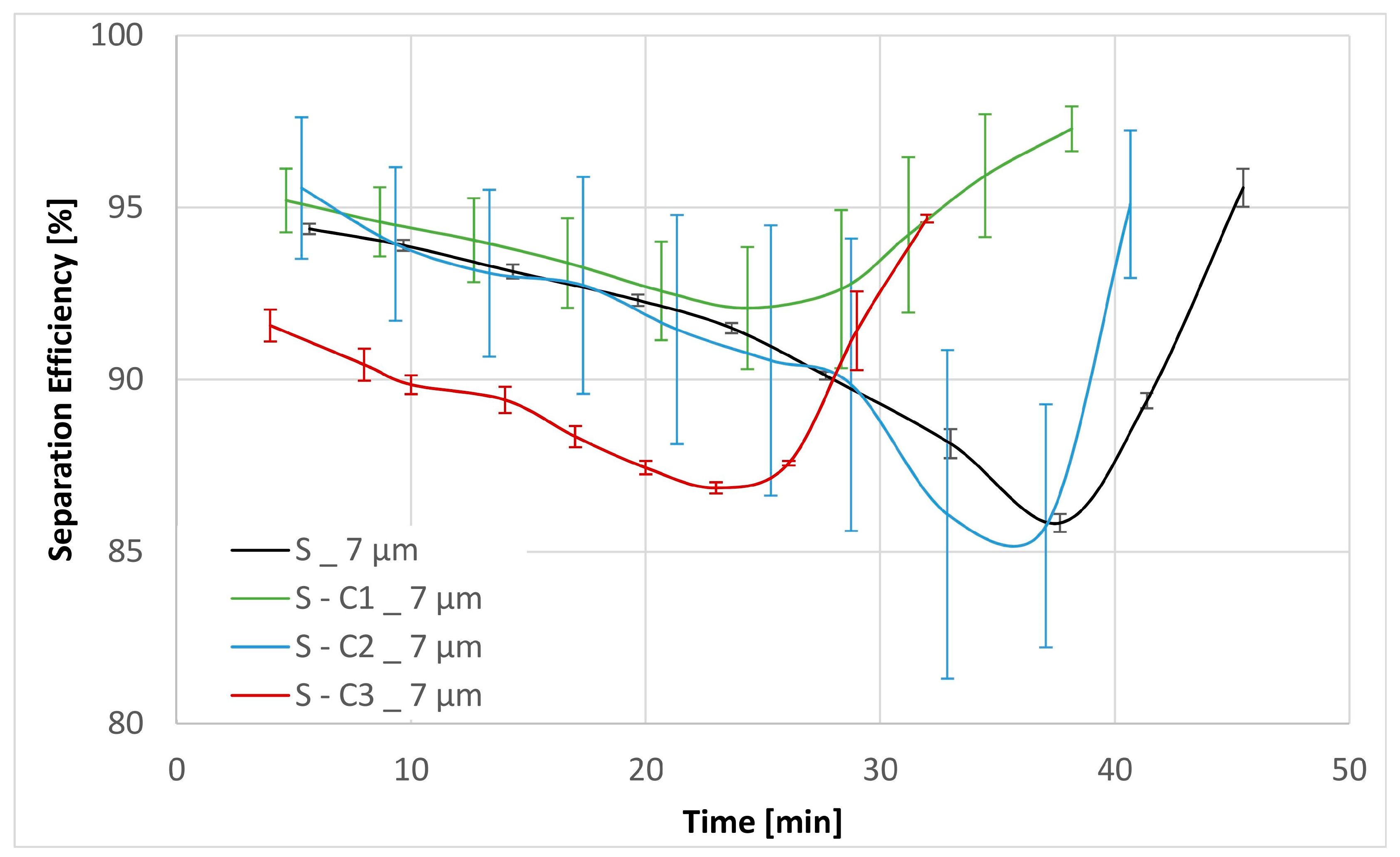

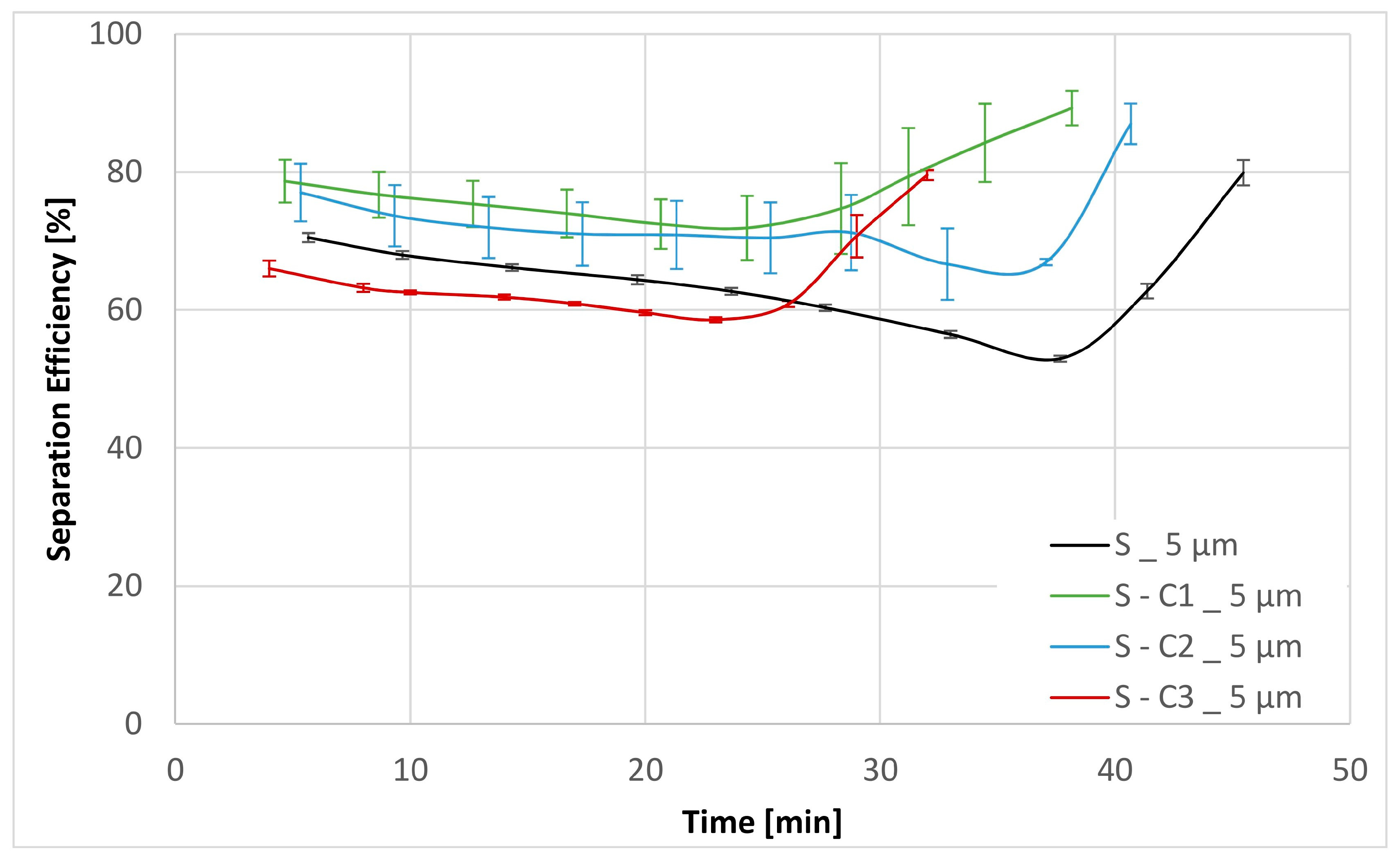

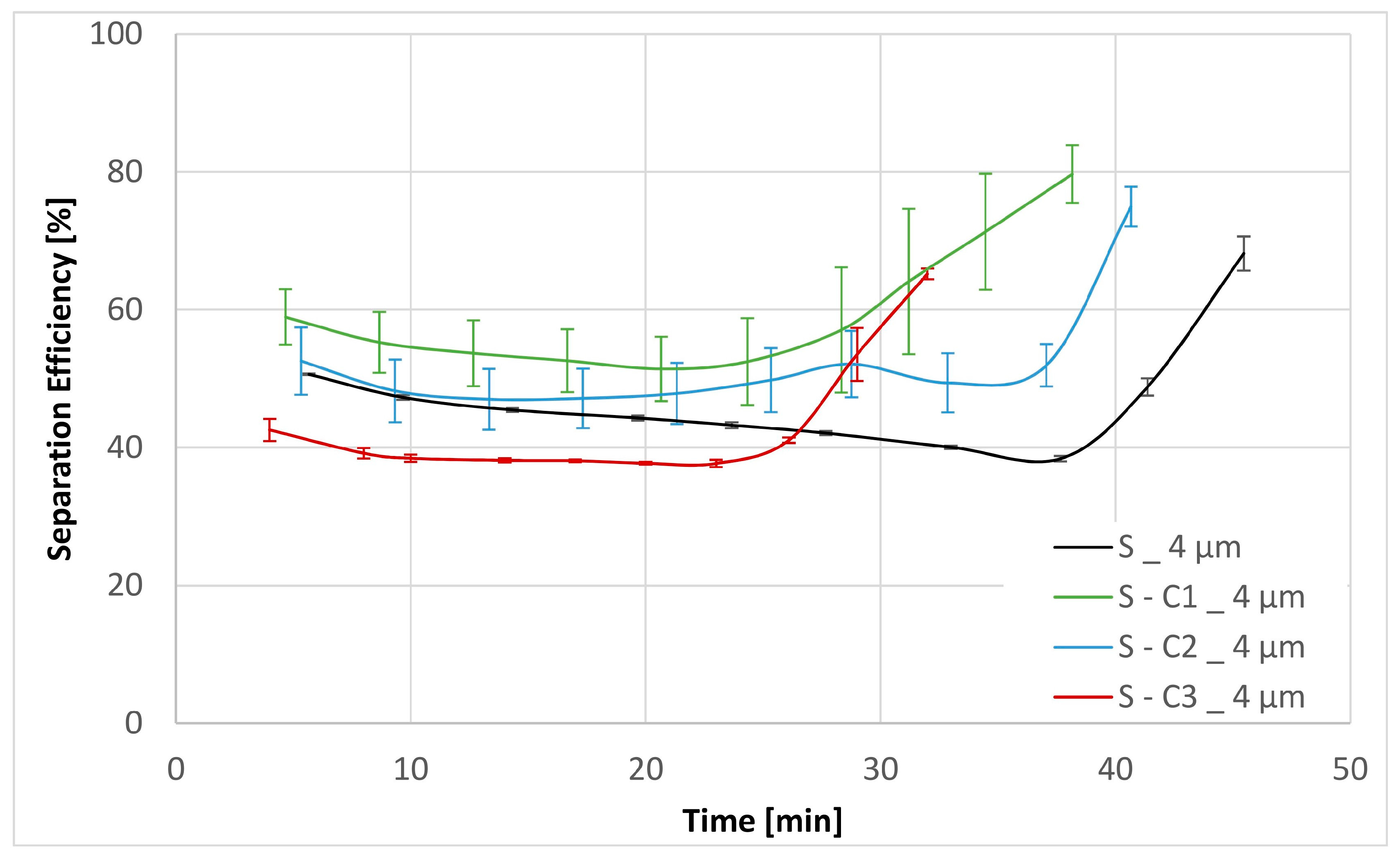

| Sample | Separation Efficiency [%] for Particle Size [µm] | DHC [g] | DPQ [bar] for 30 mm2 s−1 | DPQ [bar] for 300 mm2 s−1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >4 | >5 | >7 | >12 | 3 bar | 5 L min−1 | 10 L min−1 | 5 L min−1 | 10 L min−1 | |

| S | 46.84 | 64.41 | 91.43 | 99.63 | 2.40 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 1.76 | 3.85 |

| S-C1 | 59.65 | 77.66 | 94.19 | 99.54 | 2.15 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 1.91 | 4.15 |

| S-C2 | 52.10 | 72.68 | 91.41 | 99.41 | 2.25 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 1.34 | 2.82 |

| S-C3 | 43.17 | 64.39 | 89.76 | 99.68 | 2.25 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 4.84 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weiter, L.; Leyer, S.; Duchowski, J.K. Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristic of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 2: Chemical Modification with Surface-Active Treatment. Materials 2024, 17, 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112720

Weiter L, Leyer S, Duchowski JK. Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristic of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 2: Chemical Modification with Surface-Active Treatment. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112720

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeiter, Laura, Stephan Leyer, and John K. Duchowski. 2024. "Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristic of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 2: Chemical Modification with Surface-Active Treatment" Materials 17, no. 11: 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112720

APA StyleWeiter, L., Leyer, S., & Duchowski, J. K. (2024). Enhancement of Filtration Performance Characteristic of Glass Fiber-Based Filter Media, Part 2: Chemical Modification with Surface-Active Treatment. Materials, 17(11), 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112720