Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Ti/Mg Laminated Composites Using a Differential Temperature Rolling Process under a Protective Atmosphere

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Procedure

2.1. Materials Preparation

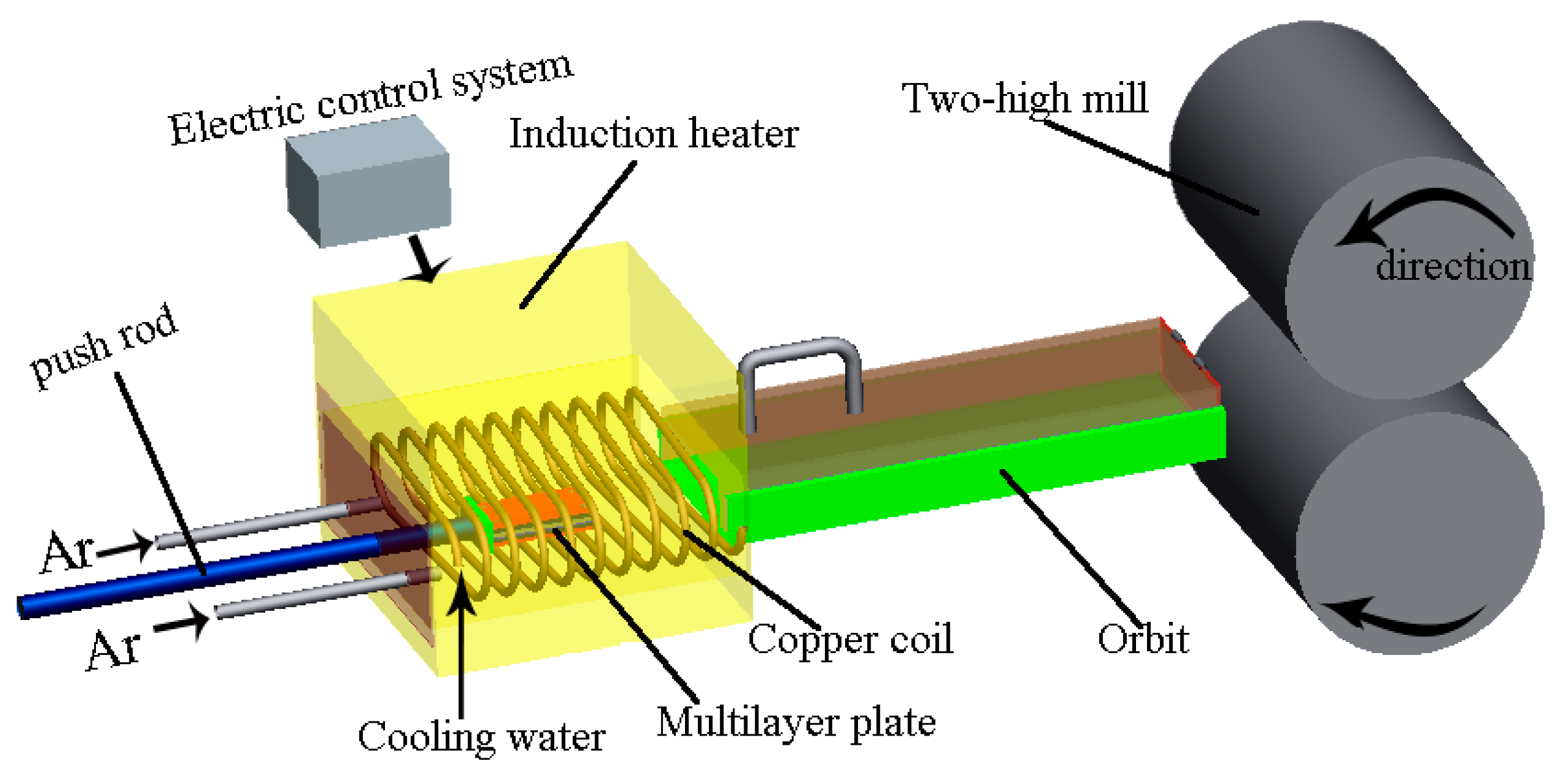

2.2. Differential Temperature Rolling Process with Induction Heating

2.2.1. Billet Arrangement

2.2.2. Differential Temperature Rolling Process

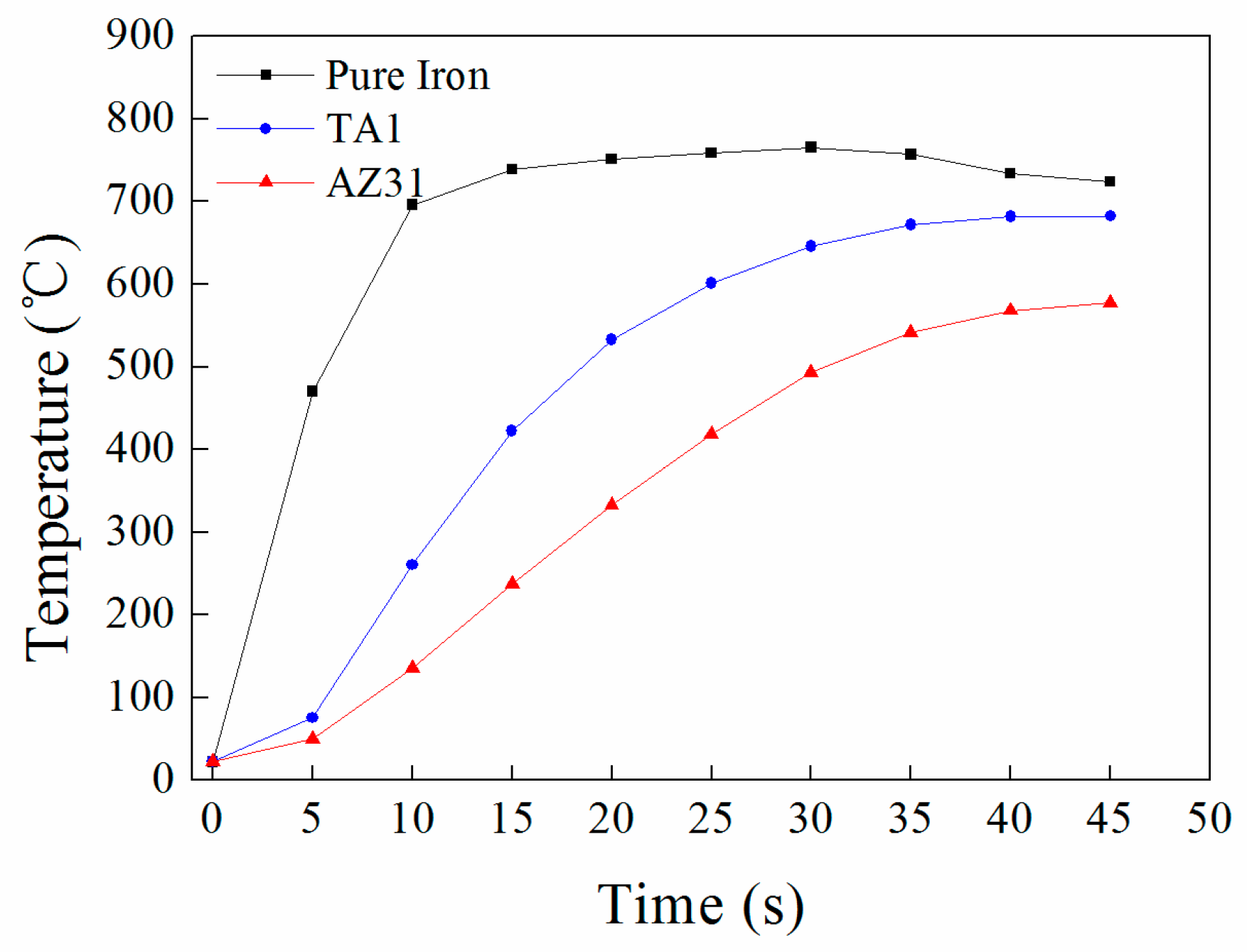

2.2.3. Determination of Rolling Process Parameters

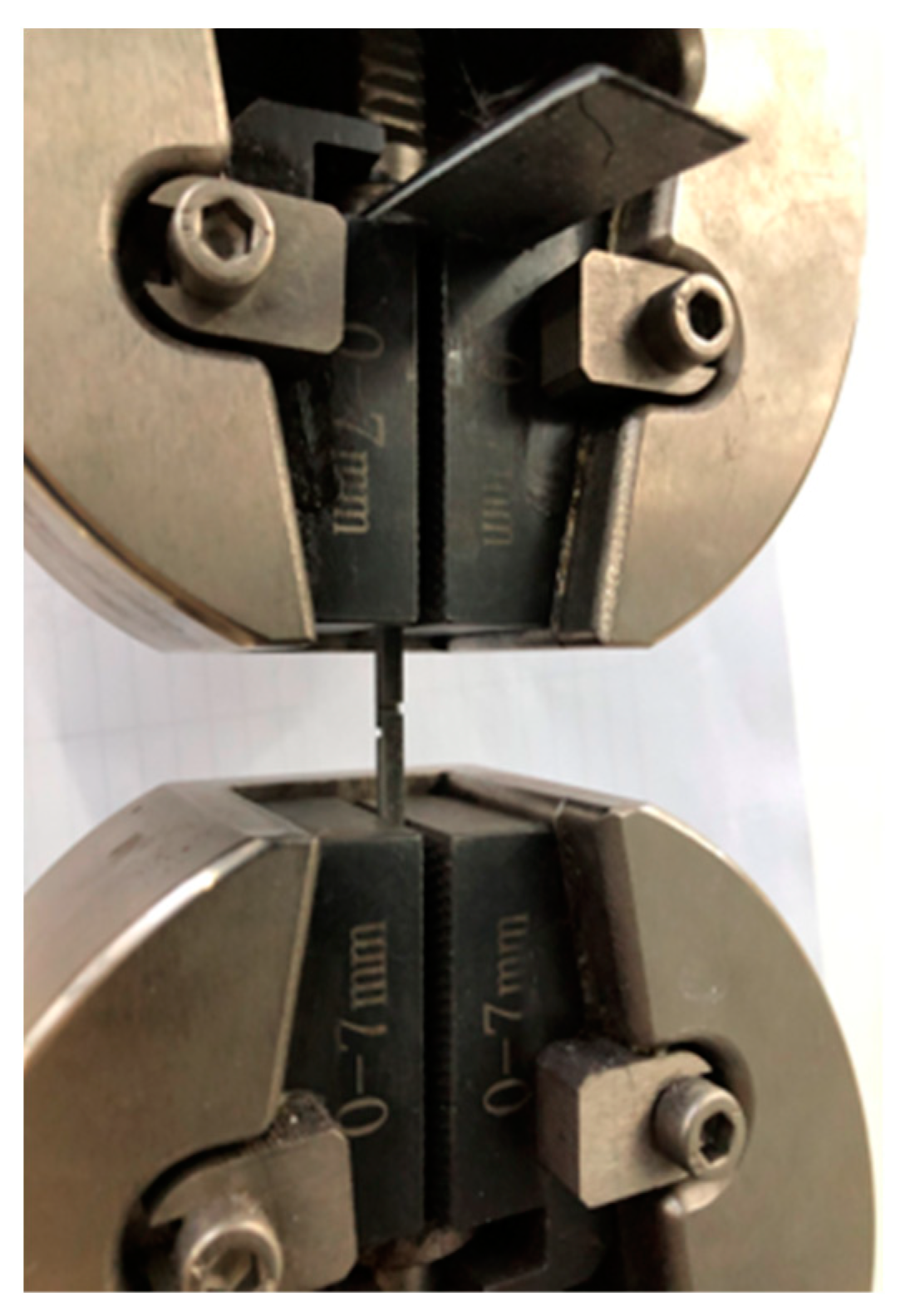

2.3. Mechanical Properties Test and Microstructure Observation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Macroscopic Bonding Property

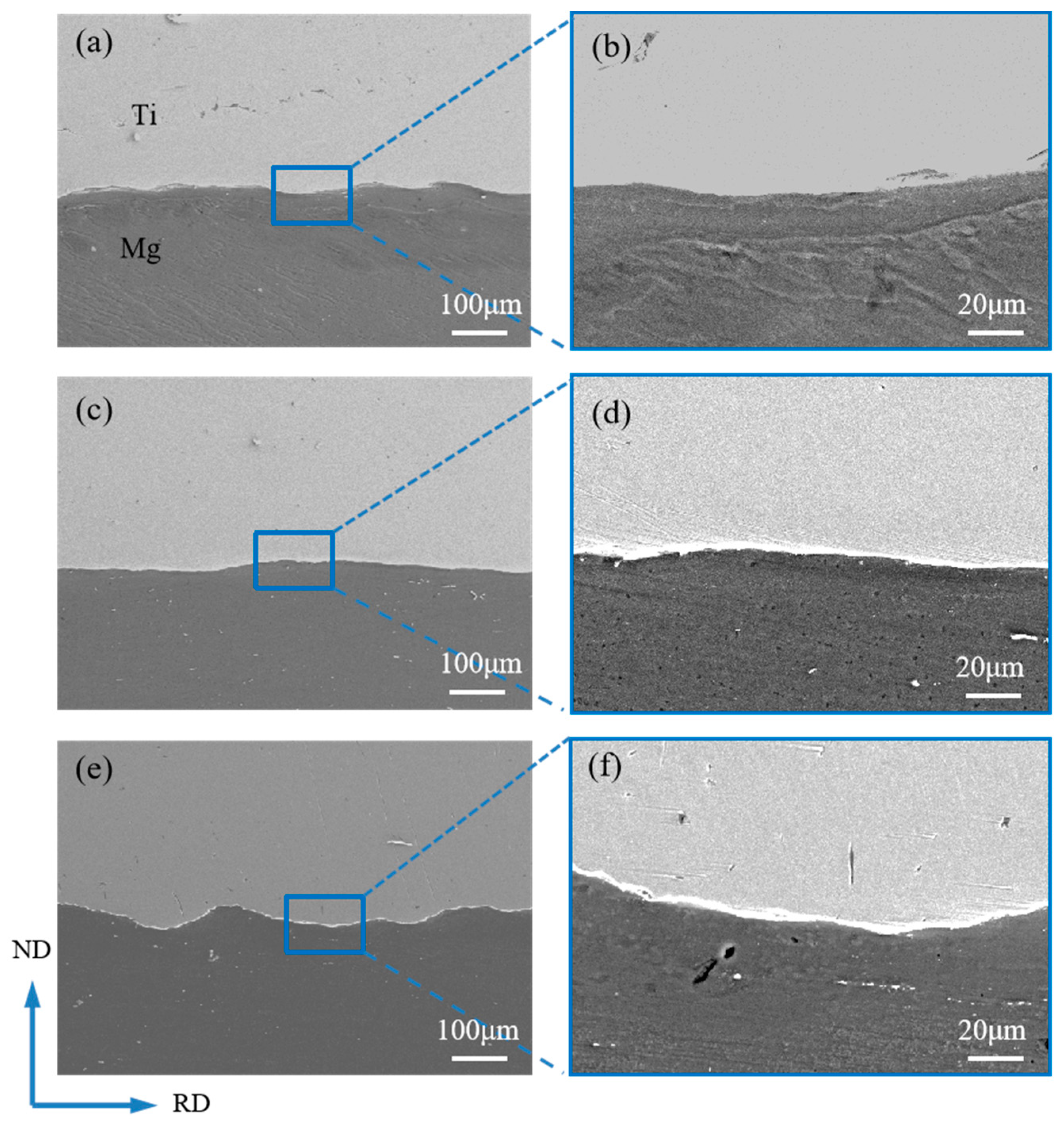

3.2. Bonding Interface and Fracture Morphology

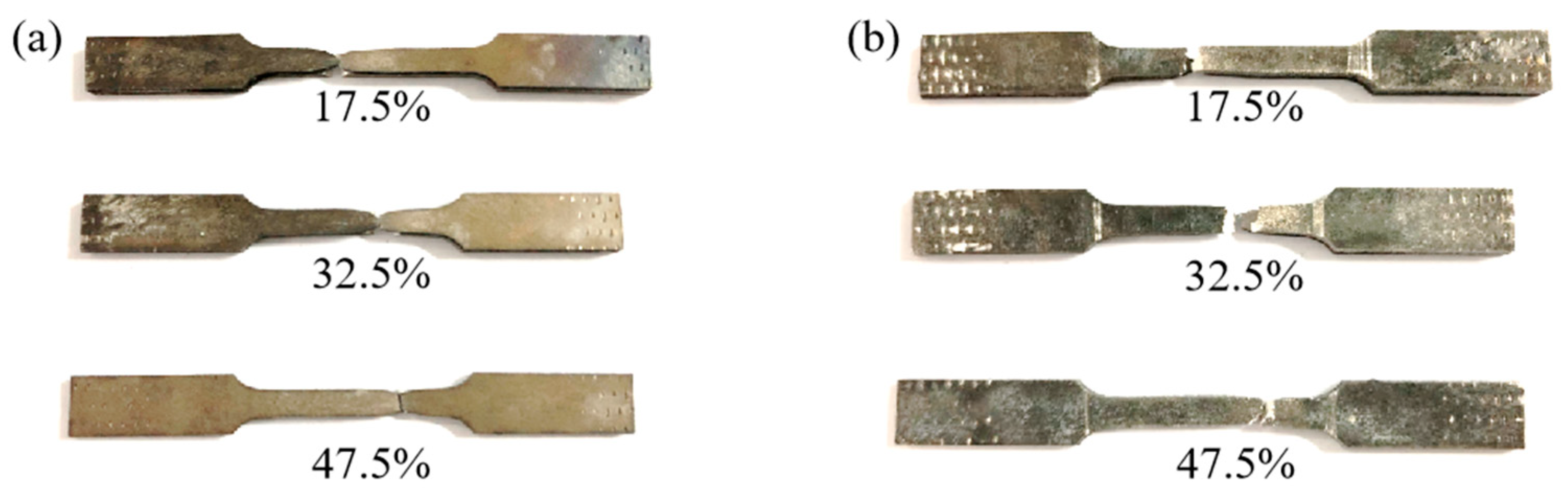

3.3. Tensile Property and Interfacial Delamination of Laminated Composites

3.4. Bonding Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- A clean and oxide-free bonding interface promotes contact between fresh metals and mutual diffusion of elements, which improves the bonding strength of the double-layer composite plates compared to those made by resistance furnace heating. Especially, it significantly enhances the bonding strength of the composite plates at a low reduction.

- (2)

- With the increase in bonding strength, the fracture surfaces on both sides of the shear fracture gradually change from brittle fracture to ductile fracture. This is attributed to the fact that at low bonding strengths, the shear fracture occurs at the interface between the two plates, while at high bonding strengths, the shear fracture occurs within the metal matrix.

- (3)

- A strong bonding interface is beneficial in preventing the propagation of interfacial cracks during the tensile testing of Ti/Mg composite plates, thereby enhancing the composite plates’ ability to resist interfacial delamination.

- (4)

- The bonding interface of the Ti/Mg composite plates prepared by differential temperature rolling with induction heating is primarily achieved through a combination of mechanical interlocking and elemental diffusion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, J.F.; She, J.; Chen, D.L.; Pan, F.S. Latest research advances on magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, E.; Aiden, B.; Matthew, B.; Chris, D.; Gordon, D.; Yvonne, D.; Stuart, B.; Tim, H.; Peter, B. Magnesium alloy applications in automotive structures. JOM 2008, 60, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vaira, V.R.; Padmanaban, R.; Mohan, D.K.; Govindaraju, M. Research and development in magnesium alloys for industrial and biomedical Applications: A Review. Met. Mater. Int. 2020, 26, 409–430. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzański, L.A.; Tański, T.; Čížek, L.; Brytan, Z. Structure and properties of magnesium cast alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 192–193, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Tang, X.H.; Liu, C.X.; Mei, D.; Wang, L.G.; Zhu, S.J.; Mikhail, Z.; Sviatlana, L.; Guan, S.K. Effect of medium renewal mode on the degradation behavior of Mg alloys for biomedical applications during the long-term in vitro test. Corros. Sci. 2024, 229, 111851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.L.; Atrens, A. Corrosion Mechanisms of magnesium alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 1999, 1, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.; Goellner, J.; Heyn, A.; Boese, E. Corrosion and corrosion testing of magnesium alloys. Mater. Corros. 2007, 58, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mo, H.T.; Tian, J.H.; Li, J.H.; Hu, X.; Xia, S.Q.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, Z.Y. A novel Ti/Al interpenetrating phase composite with enhanced mechanical properties. Mater. Lett. 2024, 357, 135723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.G.; Chen, P.; Ji, C. Solid-liquid cast-rolling bonding (SLCRB) and annealing of Ti/Al cladding strip. Mater. Des. 2017, 118, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huo, P.; Liu, W.C.; Wang, G.J.; Wang, D.M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al/Ti/Al laminated composites prepared by roll bonding. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 636, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.Z.; Sheng, L.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Huo, M.; Zhang, K.; Xing, L.W.; Zhang, G. Study on the microstructure and mechanical properties of a Ti/Mg alloy clad plate produced by explosive welding. Metals 2022, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, D.; Rubio, E.M.; Manuel, J.; Marta, M. Thicknesses/roughness relationship in Mg-Al-Mg and Mg-Ti-Mg hybrid component plates for drilled aeronautical lightweight parts. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Tang, Y.Z.; Chen, W.H.; He, W.J.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F.S. Fabrication of Mg/Ti composite with excellent strength and ductility by hot rolling. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 888, 145783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.L.; Gan, Z.Y.; Tang, H.C. Effect of composition on in vitro degradability of Ti–Mg metal-metal composites. Mat. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Q.; Wang, W.X.; Cao, X.Q.; Zhang, N. Interface bonding mechanism and mechanical behavior of AZ31B/TA2 composite plate cladded by explosive welding. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2017, 46, 640–645. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.W.; Chen, B.; Meng, S.H.; Zhang, K.P.; Song, X.G.; Zhou, L.; Feng, J.C. Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser welded-brazed AZ31/TA1 joints with AZ91 Mg based filler. Mater. Des. 2016, 99, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.T.; Zhang, F.S.; Li, J.L.; Huang, W.D. Transient liquid phase bonding of magnesium alloy (AZ31B) and titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) using aluminum interlayer. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2006, 35, 1677–1680. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, H.; Yu, H.; Qi, Z.C.; Xu, C. Mechanical properties and interfacial structure of hot-roll bonding TA2/Q235B plate using DT4 interlayer. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 695, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, T.; Ren, Z.K.; Liu, Y.M.; Huang, Q.X. Evolution mechanism of microstructure and bond strength based on interface diffusion and IMCs of Ti/steel clad plates fabricated by double-layered hot rolling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 310, 117780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, W.; Yun, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Q. A dynamic composite rolling model based on Lemaitre damage theory. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 269, 109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, F.R.; Wang, Y.Q.; Xie, G.M. Microstructural evolution and properties of Ti/Al clad plate fabricated by vacuum rolling and heat treatment. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 882, 145445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Manesh, H.D. Bond strength optimization of Ti/Cu/Ti clad composites produced by roll-bonding. Mater. Des. 2015, 81, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.Q.; Xiao, H.Q.; Lin, B.; Li, W.; Ma, K. Improving ductility and anisotropy by dynamic recrystallization in Ti/Mg laminated metal composite. Acta Metall. Sin.-Engl. 2022, 35, 1946–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.C.; Yu, C.; Xiao, H. Microstructure and bonding properties of magnesium alloy AZ31/CP-Ti clad plates fabricated by rolling bonding. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 32, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Qi, Z.C.; Yu, C.; Xu, C. Preparation and properties for Ti/Al clad plates generated by differential temperature rolling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 249, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 6396-2008; Clad Steel Plates—Mechanical and Technological Test. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 8547-2006; Titanium Clad Steel Plate. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

| Materials | C | N | H | O | Si | Fe | Al | Ca | Zn | Mn | Cu | Ti | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA1 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | - | Bal. | - |

| AZ31B | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.03 | 3.1 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.01 | 0.15 | Bal. |

| Materials | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Shear Strength (MPa) | Fracture Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA1 | 434 | 328 | 285 | 25.3 |

| AZ31B | 226 | 160 | 128 | 12.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wen, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, X.; Gu, D.; Chen, B.; Jiang, X. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Ti/Mg Laminated Composites Using a Differential Temperature Rolling Process under a Protective Atmosphere. Materials 2024, 17, 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112753

Qi Z, Jia Z, Wen X, Xiao H, Liu X, Gu D, Chen B, Jiang X. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Ti/Mg Laminated Composites Using a Differential Temperature Rolling Process under a Protective Atmosphere. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112753

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Zichen, Zhengchi Jia, Xiaoqing Wen, Hong Xiao, Xiao Liu, Dawei Gu, Bo Chen, and Xujian Jiang. 2024. "Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Ti/Mg Laminated Composites Using a Differential Temperature Rolling Process under a Protective Atmosphere" Materials 17, no. 11: 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112753