The Effect of Sputtering Sequence Engineering in Superlattice-like Sb-Rich-Based Phase Change Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Material Characterization

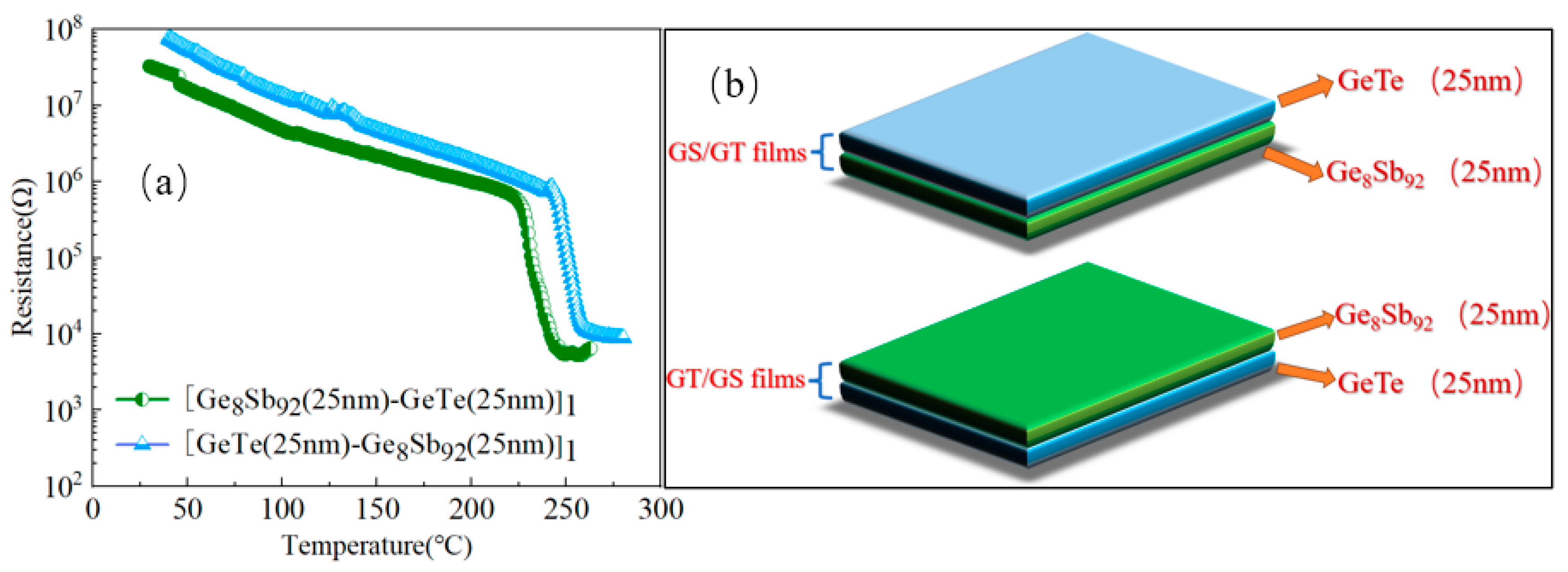

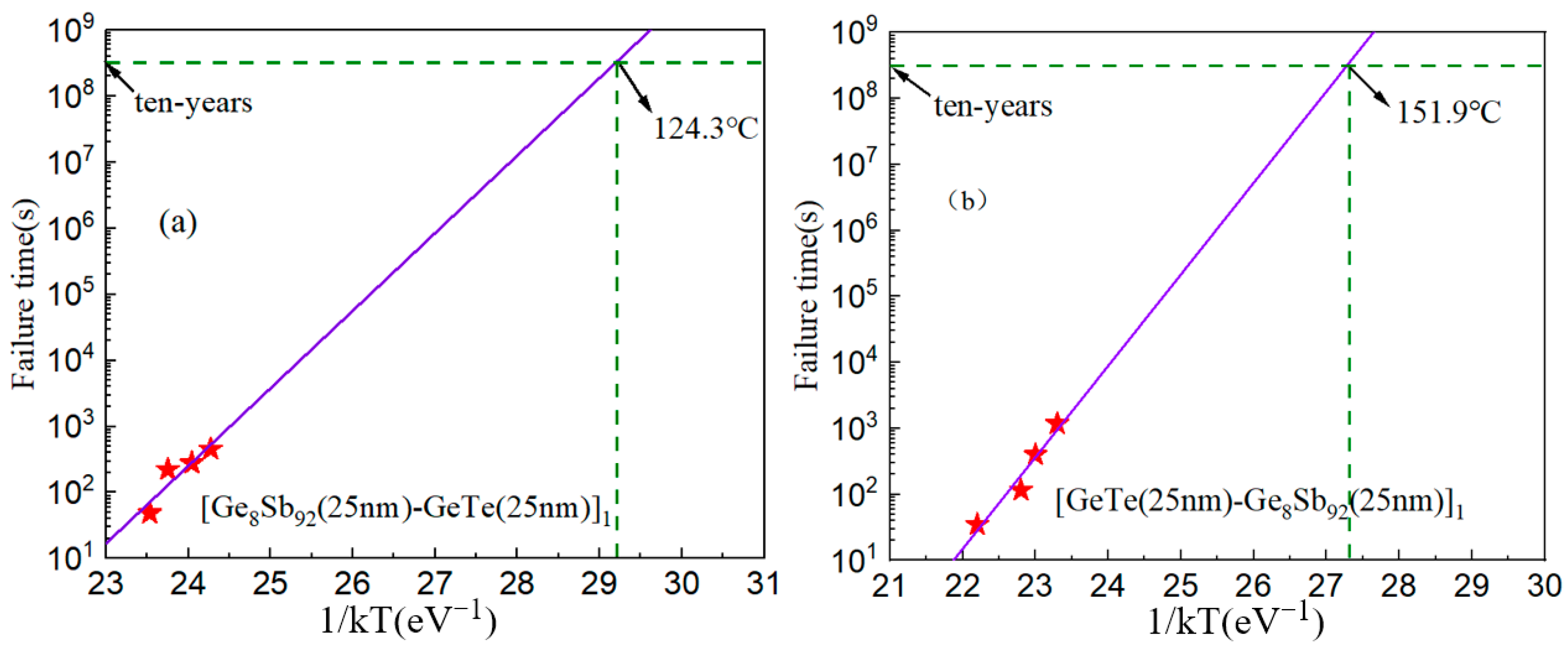

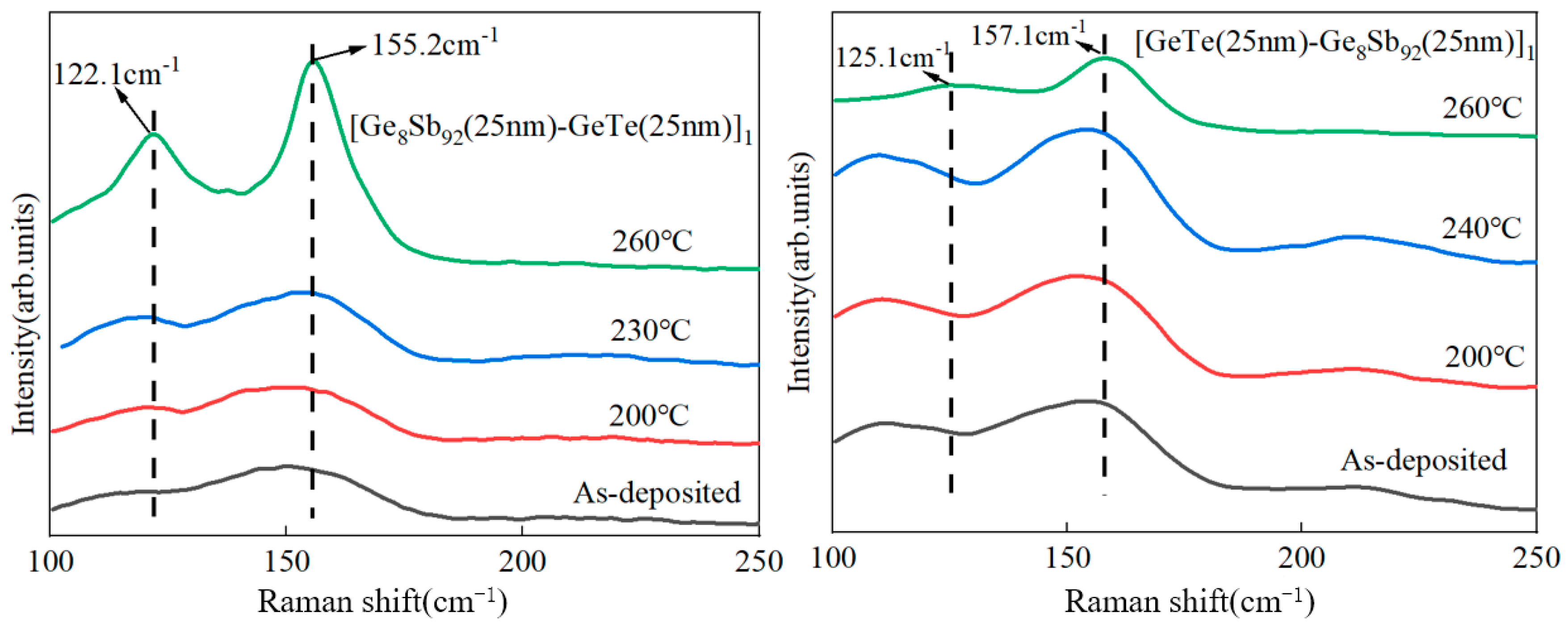

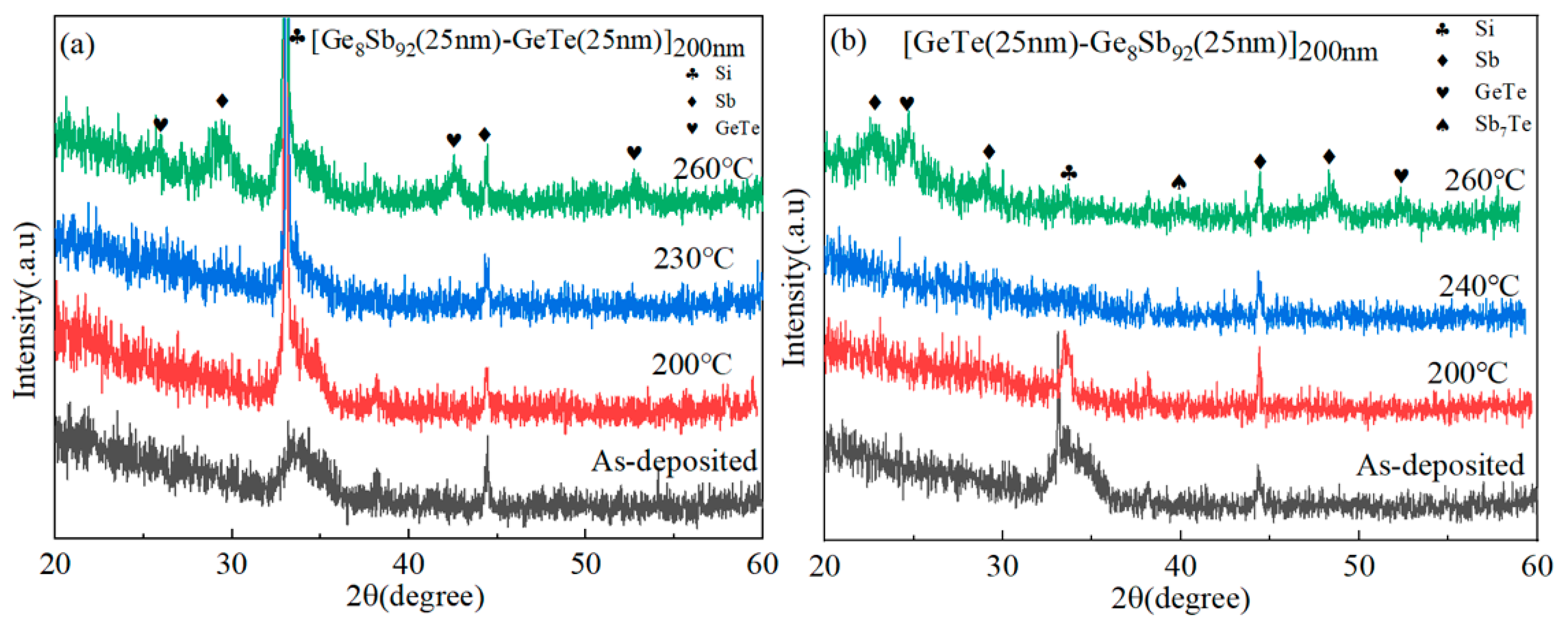

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ielmini, D.; Lacaita, A.L. Phase change materials in non-volatile storage. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, L.; Song, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Rao, F.; Ren, K.; Song, S.; Liu, B.; Feng, S. Nitrogen-doped Sb-rich Si-Sb-Te phase-change material for high-performance phase-change memory. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 7324–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.E. The changing phase of data storage. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuttig, M.; Yamada, N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Song, S.; Chen, X.; Yan, S.; Lv, S.; Xin, T.; Song, Z. Enhanced performance of phase change memory by grain size reduction. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 3585–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orava, J.; Greer, A.Á.; Gholipour, B.; Hewak, D.; Smith, C. Characterization of supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 and its crystallization by ultrafast-heating calorimetry. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Chen, H.; Jung, A.L. The structure and crystallization characteristics of phase change optical disk material Ge1Sb2Te4. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 78, 2338–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, L.; Huang, S.; Miao, X.; Chong, T.C. Phase transformation of Ge1Sb4Te7 films induced by single femtosecond pulse. Proc. SPIE 2004, 5380, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Si, C.; Zhou, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, Z. Yttrium-doped Sb2Te3: A promising material for phase-change memory. ACS Appl. Mater. 2016, 8, 26126–26134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, R.M.; Raoux, S. Crystallization dynamics of nitrogen-doped Ge2Sb2Te5. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, M.; Xu, K.; Qian, H.; Tong, H.; Cheng, X.; Wu, L.; Xu, M.; Miao, X. Increasing the Atomic Packing Efficiency of Phase-Change Memory Glass to Reduce the Density Change upon Crystallization. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2018, 4, 1800127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, T.; Shi, L.; Zhao, R.; Tan, P.; Li, J.; Lee, H.; Miao, X.; Du, A.; Tung, C. Phase change random access memory cell with superlattice-like structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 122114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, S.; Wu, W.; Zhai, J.; Song, S.; Song, Z. Investigation of multilayer SnSb4/ZnSb thin films for phase change memory applications. Appl. Phys. Express 2017, 10, 055504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, R.; Wu, P.; Zhai, J.; Lai, T.; Song, S.; Song, Z. High speed and high reliability in Ge8Sb92/Ga30Sb70 stacked thin films for phase change memory applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 653, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhai, J.; Wen, T.; Lai, T.; Song, S.; Song, Z. Superlattice-like Ge8Sb92/Ge thin films for high speed and low power consumption phase change memory application. Scr. Mater. 2014, 93, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, S.; Lai, T.; Song, S.; Song, Z.; Zhai, J. Al19Sb54Se27 material for high stability and high-speed phase-change memory applications. Scr. Mater 2013, 69, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhai, J. Atomistic insights into the enhanced stability and phase change speed of Al–Sb phase change materials. Mater. Lett. 2019, 234, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Agarwal, R. Phase-change Ge−Sb nanowires: Synthesis, memory switching, and phase-instability. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 2103–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Rao, F.; Wu, L.; Song, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Song, H.; Yang, P.; Chu, J. Homogeneous phase W–Ge–Te material with improved overall phase-change properties for future nonvolatile memory. Acta Mater. 2014, 74, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Lai, T.; Song, S.; Song, Z. Multi-level storage and ultra-high speed of superlattice-like Ge50Te50/Ge8Sb92 thin film for phase-change memory application. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 405206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wu, P.; He, Z.; Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Lai, T. Study of crystallization and thermal stability of superlattice-like SnSb4-GeTe thin films. Thin Solid Films 2017, 625, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhai, J.; Song, J.; Wu, P.; Lai, T.; Song, S.; Song, Z. Multilayer SnSb4–SbSe thin films for phase change materials possessing ultrafast phase change speed and enhanced stability. ACS Appl. Mater. 2017, 9, 27004–27013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, I.; Weidenhof, V.; Njoroge, W.; Franz, P.; Wuttig, M. Structural transformations of Ge2Sb2Te5 films studied by electrical resistance measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 87, 4130–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction kinetics in differential thermal analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perniola, L.; Sousa, V.; Fantini, A.; Arbaoui, E.; Bastard, A.; Armand, M.; Fargeix, A.; Jahan, C.; Nodin, J.-F.; Persico, A. Electrical behavior of phase-change memory cells based on GeTe. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2010, 31, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Nie, Q.; Shen, X. Phase change behavior of pseudo-binary ZnTe-ZnSb material. Mater. Lett. 2018, 213, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomban, P.; Havel, M. Raman imaging of stress-induced phase transformation in transparent ZnSe ceramic and sapphire single crystals. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2002, 33, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.J.; Qin, J.; Gao, P.F.; Shi, W.M.; Wang, L.J. Studies on the Structure and Properties of ZnSb Thin Films Deposited under Various Sputtering Conditions. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 748, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, K.; Yannopoulos, S.; Kolobov, A.; Fons, P.; Tominaga, J. Raman scattering study of GeTe and Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change materials. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2007, 68, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Song, S.; Shen, X.; Song, Z.; Wang, G.; Dai, S. Study on phase change properties of binary GaSb doped Sb–Se film. Thin Solid Films 2015, 589, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, S. Size-dependent Raman red shifts of semiconductor nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14193–14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoux, S.; Cabral, C.; Krusin-Elbaum, L.; Jordan-Sweet, J.L.; Virwani, K.; Hitzbleck, M.; Salinga, M.; Madan, A.; Pinto, T.L. Phase transitions in Ge–Sb phase change materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 064918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Cai, D.L.; Xue, Y.; Guo, T.Q.; Song, S.N.; Song, Z.T. Sb-rich CuSbTe material: A candidate for high-speed and high-density phase change memory application. Mat Sci Semicon Proc. 2019, 103, 104625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pieterson, L.; Van Schijndel, M.; Rijpers, J.; Kaiser, M. Te-free, Sb-based phase-change materials for high-speed rewritable optical recording. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 1373–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoux, S.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Jordan-Sweet, J.L.; Munoz, B.; Hitzbleck, M. Influence of interfaces and doping on the crystallization temperature of Ge–Sb. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 183114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, A.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. The Effect of Sputtering Sequence Engineering in Superlattice-like Sb-Rich-Based Phase Change Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112773

Li A, Liu R, Liu L, Chen Y, Zhou X. The Effect of Sputtering Sequence Engineering in Superlattice-like Sb-Rich-Based Phase Change Materials. Materials. 2024; 17(11):2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112773

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Anding, Ruirui Liu, Liu Liu, Yukun Chen, and Xiao Zhou. 2024. "The Effect of Sputtering Sequence Engineering in Superlattice-like Sb-Rich-Based Phase Change Materials" Materials 17, no. 11: 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112773

APA StyleLi, A., Liu, R., Liu, L., Chen, Y., & Zhou, X. (2024). The Effect of Sputtering Sequence Engineering in Superlattice-like Sb-Rich-Based Phase Change Materials. Materials, 17(11), 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17112773