Deposition Contribution Rates and Simulation Model Refinement for Polysilicon Films Deposited by Large-Sized Tubular Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Reactors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

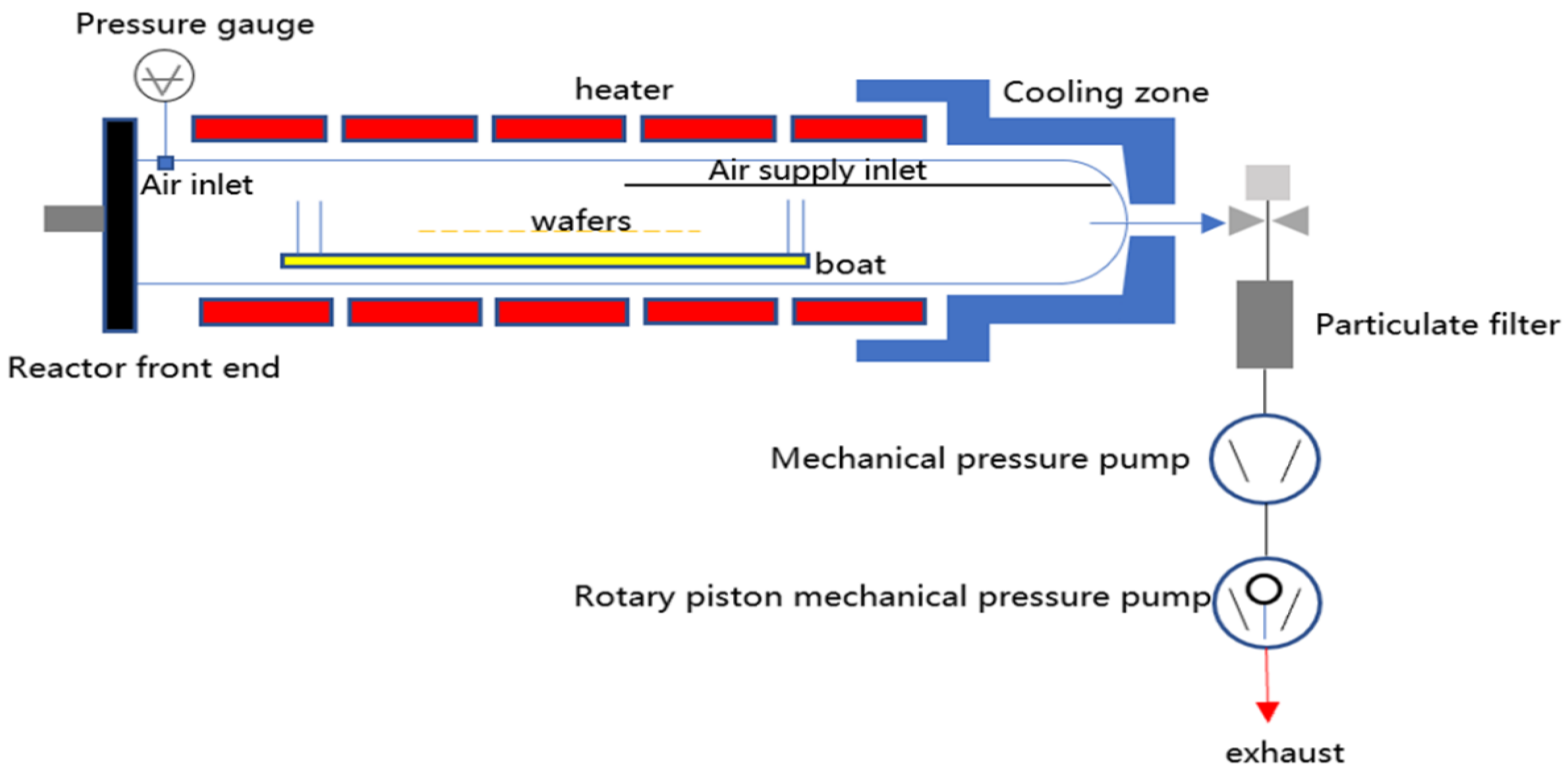

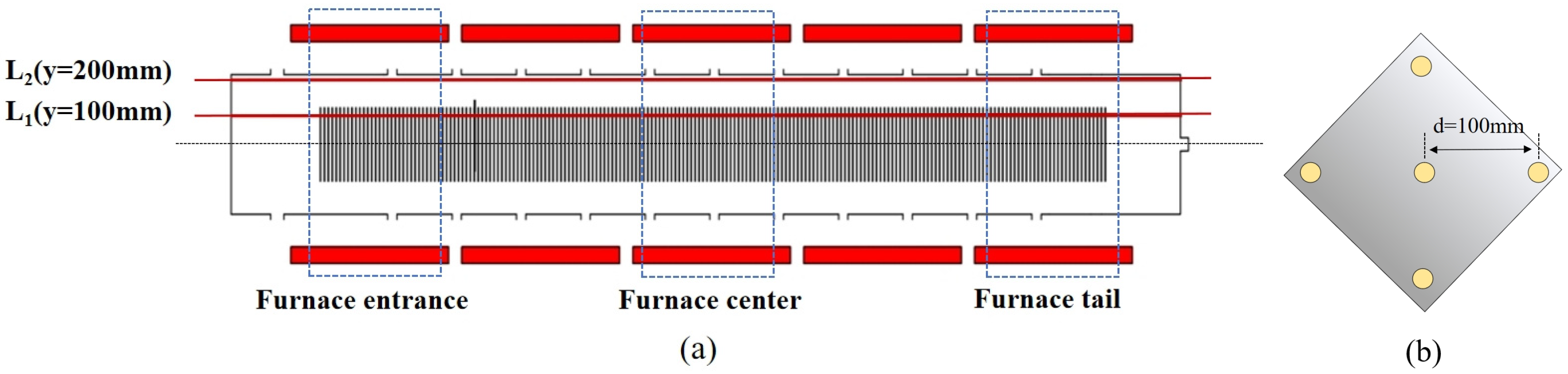

2. Experimental Issues and Simulation Scheme

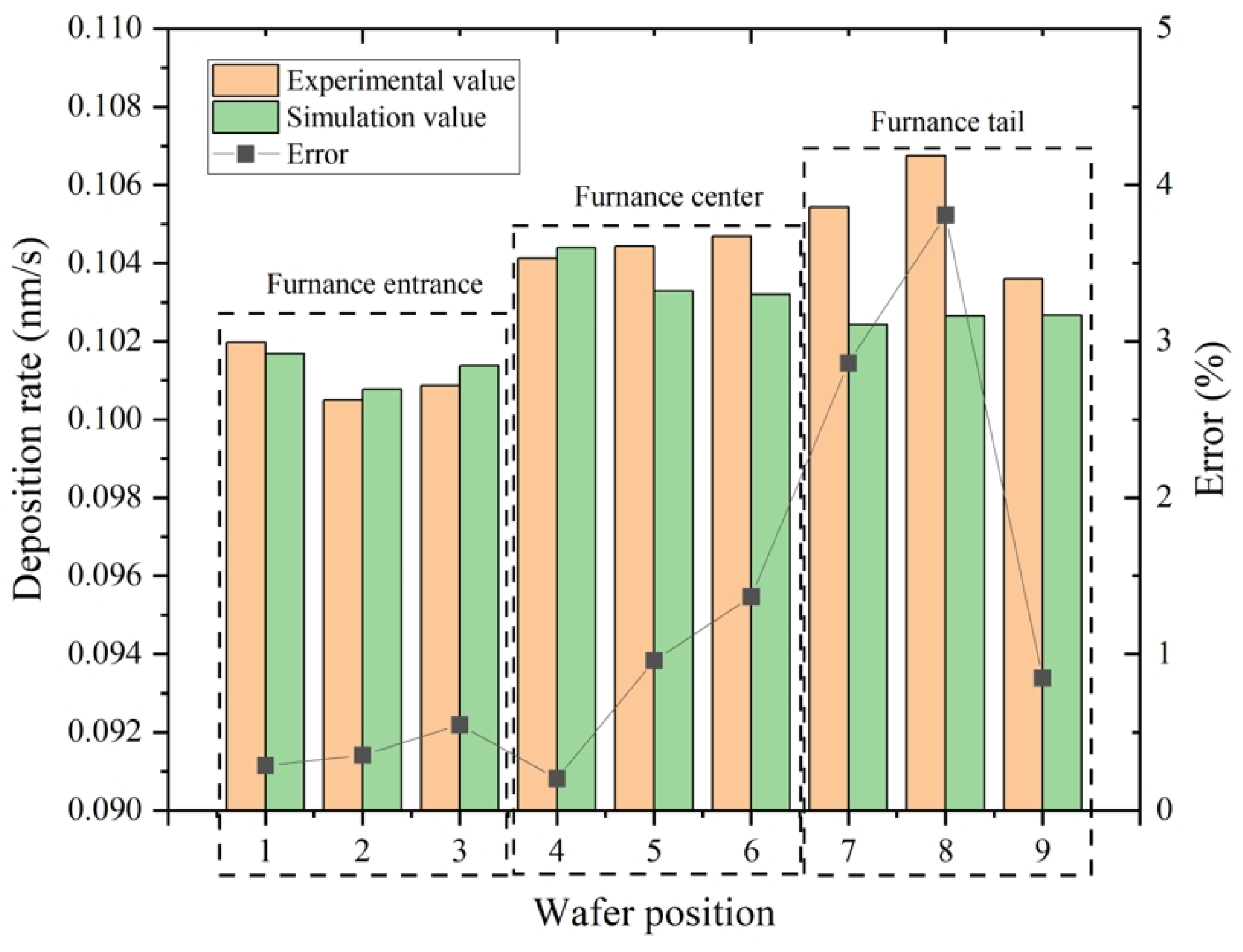

3. Model Verification

4. Results and Discussion

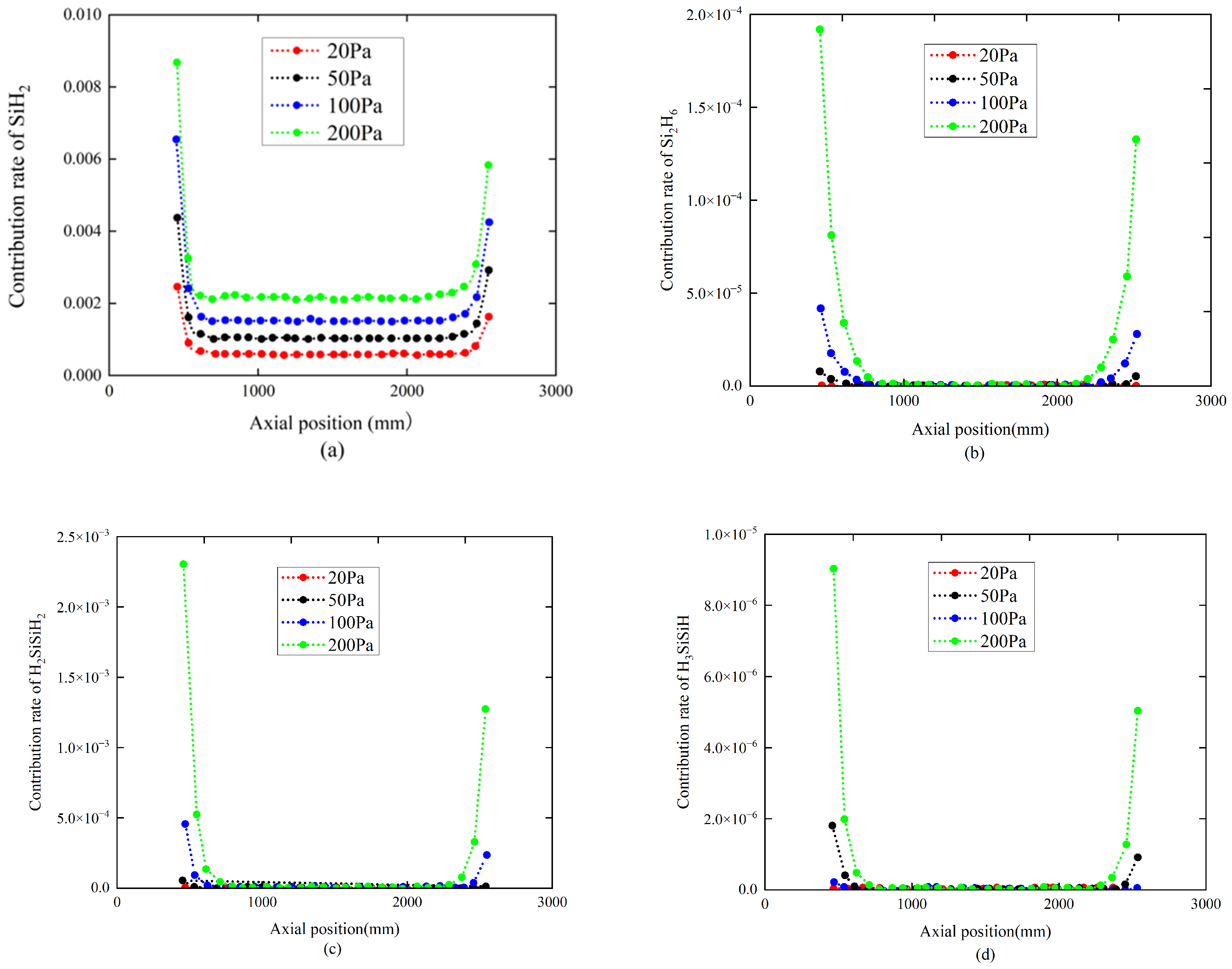

4.1. The Influence of Pressure

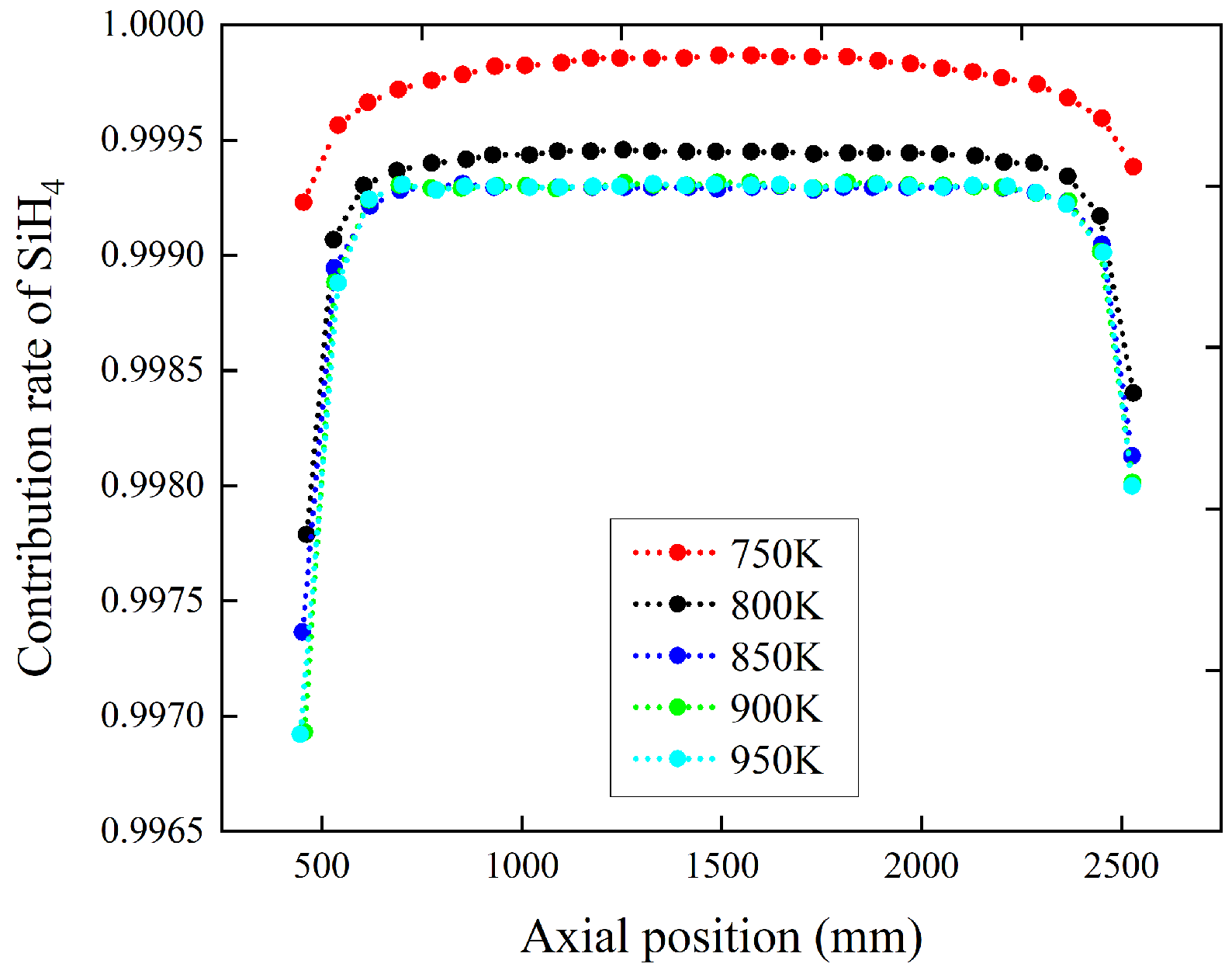

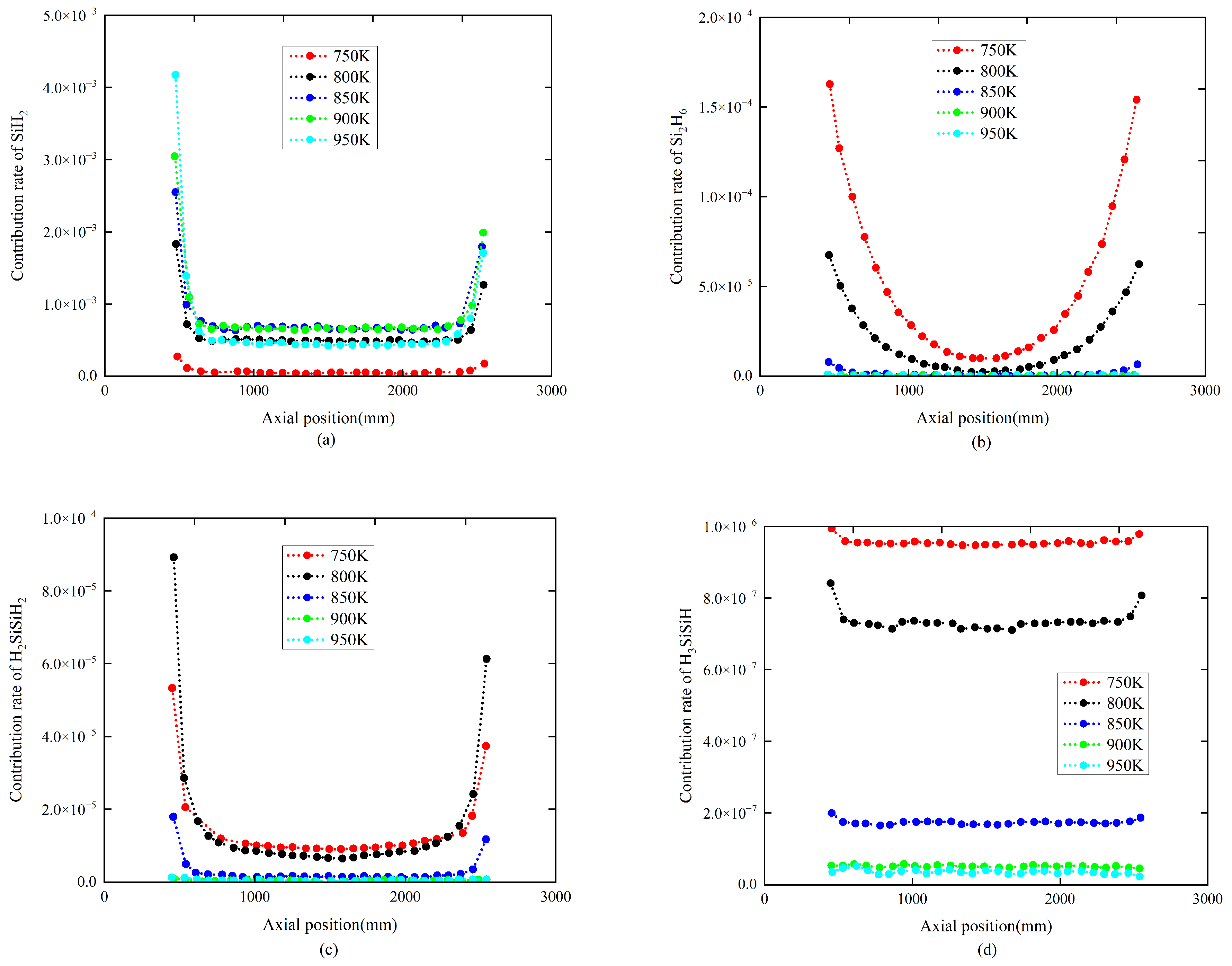

4.2. The Influence of Temperature

5. The Proposal of the Simplified Reaction Mechanism Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Padhamnath, P.; Nandakumar, N.; Kitz, B.J.; Balaji, N.; Naval, M.J.; Shanmugam, V.; Duttagupta, S. High-quality doped polysilicon using low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD). Energy Procedia 2018, 150, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Lan, Z.X.; Zhao, L.; Xu, F.; Xu, J. On the presence of oxy phosphorus bonds in TOPCon solar cell poly silicon films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 246, 111910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, M. Studies of low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) of polysilicon (chemical vapor deposition). eLIBRARY.RU 1992, 6429. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Tong, H.; Quan, C.; Cai, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, K.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, C.H.; Yan, B.; Gao, P.; et al. Theoretical exploration towards high-efficiency tunnel oxide passivated carrier-selective contacts (TOPCon) solar cells. Sol. Energy 2017, 155, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, C.S.; Huang, Y.; Liao, M.; Tong, H.; Al-Jassim, M.; Gao, P.; Shou, C.; Zhou, X.; et al. Carrier transport through the ultrathin silicon-oxide layer in tunnel oxide passivated contact (TOPCon) c-Si solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 187, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lv, B.; Liang, H.; Wen, Z. Simulation and optimization of polysilicon thin film deposition in a 3000 mm tubular LPCVD reactor. Sol. Energy 2023, 253, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.N.; Yan, D.; Nguyen, C.P.T.; Kho, T.; Guthrey, H.; Seidel, J.; Al-Jassim, M.; Cuevas, A.; Macdonald, D.; Ngu-yen, H.T. Morphology, microstructure, and doping behavior: A comparison between different deposition methods for poly-Si/SiOx passivating contacts. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2021, 29, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, X.; Fan, J.; Deng, M.; Ye, H.; Qian, C.; Zhang, P.; Xing, G.; Yu, J. Effects of LPCVD-deposited thin intrinsic silicon films on the performance of boron-doped polysilicon passivating contacts. Sol. Energy 2023, 264, 112078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, M.; Radhakrishnan, H.S.; Payo, M.R.; Choulat, P.; Badran, H.; van der Heide, A.; Govaerts, J.; Duerinckx, F.; Tous, L.; Hajjiah, A.; et al. Large-area bifacial n-TOPCon solar cells with in situ phosphorus-doped LPCVD poly-Si passivating contacts. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 236, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ren, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, W.; Cai, X.; Zhao, B. Study on effect of process and structure parameters on SiNxHy growth by in-line PECVD. Sol. Energy 2020, 198, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, J.; Liao, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, H. Multi-field simulation and optimization of SiNx: H thin-film deposition by large-sized tubular LF-PECVD. Sol. Energy 2021, 228, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, W.; Chen, T. An investigation on improving the homogeneity of plasma generated by linear microwave plasma source with a length of 1550 mm. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 025401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liao, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, T.; Lv, B.; Peng, Y. Effects of process parameters and chamber structure on plasma uniformity in a large-area capacitively coupled discharge. Vacuum 2022, 195, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltrin, M.E.; Kee, R.J.; Miller, J.A. A mathematical model of the coupled fluid mechanics and chemical kinetics in a chemical vapor deposition reactor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1984, 131, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltrin, M.E.; Kee, R.J.; Evans, G.H. A mathematical model of the fluid mechanics and gas-phase chemistry in a rotating disk chemical vapor deposition reactor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltrin, M.E.; Kee, R.J.; Miller, J.A. A mathematical model of silicon chemical vapor deposition: Further refinements and the effects of thermal diffusion. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1986, 133, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Takagi, S.; Kai, T.; Shiozawa, J.; Maki, K. Multiscale Analysis of Silicon Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposi-tion. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 7855–7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, C.R. A mathematical model of the hydrodynamics and gas-phase reactions in silicon LPCVD in a single-wafer reactor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, R.; Ogino, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Shimogaki, Y. Predictive model extraction for polysilicon low-pressure chemical vapor deposition in a commercial scale reactor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, D328–D333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houf, W.G.; Grcar, J.F.; Breiland, W.G. A model for low pressure chemical vapor deposition in a hot-wall tubular reactor. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 1993, 17, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.; Coltrin, M.E.; Breiland, W.G. Laser-induced fluorescence measurements and kinetic analysis of Si atom formation in a rotating disk chemical vapor deposition reactor. J. Phys. Chemi. 1994, 98, 10138–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, C.R. Computational modeling of transport phenomena and detailed chemistry in chemical vapor deposition—A benchmark solution. Thin Solid Films 2000, 365, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, C.R.; Van Der Meer, T.H.; Hoogendoorn, C.J. A mathematical model for LPCVD in a single wafer reactor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhou, J. Effect of power ratio of side/top heaters on the performance and growth of multi-crystalline silicon ingots. Mater. Lett. 2022, 306, 130968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOPCon Will Remain Mainstream in the Next Five Years. 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/IfUY4QvdZg_hbdbAb5Djcg (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Padhamnath, P.; Nampalli, N.; Nandakumar, N.; Buatis, J.K.; Naval, M.J.; Aberle, A.G.; Duttagupta, S. Optoelectrical properties of high-performance low-pressure chemical vapor deposited phosphorus-doped polysilicon layers for passivating con-tact solar cells. Thin Solid Films 2020, 699, 137886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple-Boyer, P.; Rousset, B.; Scheid, E. Influences of deposition and crystallization kinetics on the properties of silicon films deposited by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition from SiH4 and diSiH4. Thin Solid Films 2010, 518, 6897–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.K.; Bose, S.; Das, G.; Acharyya, S.; Nandi, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sengupta, A. Fundamentals, present status and future perspective of TOPCon solar cells: A comprehensive review. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 30, 101917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Luan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wu, J.; Lu, Z. Numerical modeling of SiC by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition from methyltrichlorosilane. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Yadav, M.K.; Bag, A. Transition from thin film to nanostructure in low pressure chemical vapor deposition growth of β-Ga2O3: Impact of metal gallium source. Thin Solid Films 2020, 709, 138234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanneboina, V. Detailed review on c-Si/a-Si: H heterojunction solar cells in perspective of experimental and simulation. Mi-Croelectron. Eng. 2022, 265, 111884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, R.; Pamuru, V. Making of crystalline silicon solar cells. In Elsevier eBooks; Solar PV Power; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 71–134. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts, W.L.M.; De Croon, M.H.J.M.; Marin, G.B. Low pressure chemical vapor deposition of polysilicon: Validation and assessment of reactor models. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996, 51, 2109–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaro, C.; Duverneuil, P.; Couderc, J.P. Thermal and kinetic modelling of low-pressure chemical vapor deposition hot-wall tubular reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 3827–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, K.; Liu, A.; Jia, R.; Bao, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, S.; et al. The impacts of LPCVD wrap-around on the performance of n-type tunnel oxide passivated contact c-Si solar cell. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2020, 20, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, W.; Yuan, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J. Influence of SiOx film thickness on electrical performance and efficiency of TOPCon solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 208, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL. CFD Module User’s Guide, COMSOL Multiphysics® v. 5.6; COMSOL: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 591–605. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts, W.L.M.; de Croon, M.H.J.M.; Marin, G.B. The kinetics of the low-pressure chemical vapor deposition of poly-crystalline silicon from SiH4. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhawan, S.; McMurry, P.H.; Swihart, M.T.; Suh, S.M.; Girshick, S.L.; Campbell, S.A.; Brockmann, J.E. An experimental and numerical study of particle nucleation and growth during low-pressure thermal decomposition of SiH4. J. Aerosol Sci. 2003, 34, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction Equation | A (mol, cm3, s) | β (-) | E (J/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.28 × 1010 | 0 | 215,800 | |

| 3.53 × 1010 | 0 | 163,300 | |

| 9.68 × 1010 | 0 | 180,600 | |

| 6.02 × 1010 | 0 | 4200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Zhan, J.; Lv, B.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, B. Deposition Contribution Rates and Simulation Model Refinement for Polysilicon Films Deposited by Large-Sized Tubular Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Reactors. Materials 2024, 17, 5952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17235952

Zhou J, Zhan J, Lv B, Guo Y, Jiang B. Deposition Contribution Rates and Simulation Model Refinement for Polysilicon Films Deposited by Large-Sized Tubular Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Reactors. Materials. 2024; 17(23):5952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17235952

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jicheng, Jianyong Zhan, Bowen Lv, Yan Guo, and Bingchun Jiang. 2024. "Deposition Contribution Rates and Simulation Model Refinement for Polysilicon Films Deposited by Large-Sized Tubular Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Reactors" Materials 17, no. 23: 5952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17235952

APA StyleZhou, J., Zhan, J., Lv, B., Guo, Y., & Jiang, B. (2024). Deposition Contribution Rates and Simulation Model Refinement for Polysilicon Films Deposited by Large-Sized Tubular Low-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Reactors. Materials, 17(23), 5952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17235952