Transition Boundary from Laminar to Turbulent Flow of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Slurry—Experimental Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The mPCM Slurry

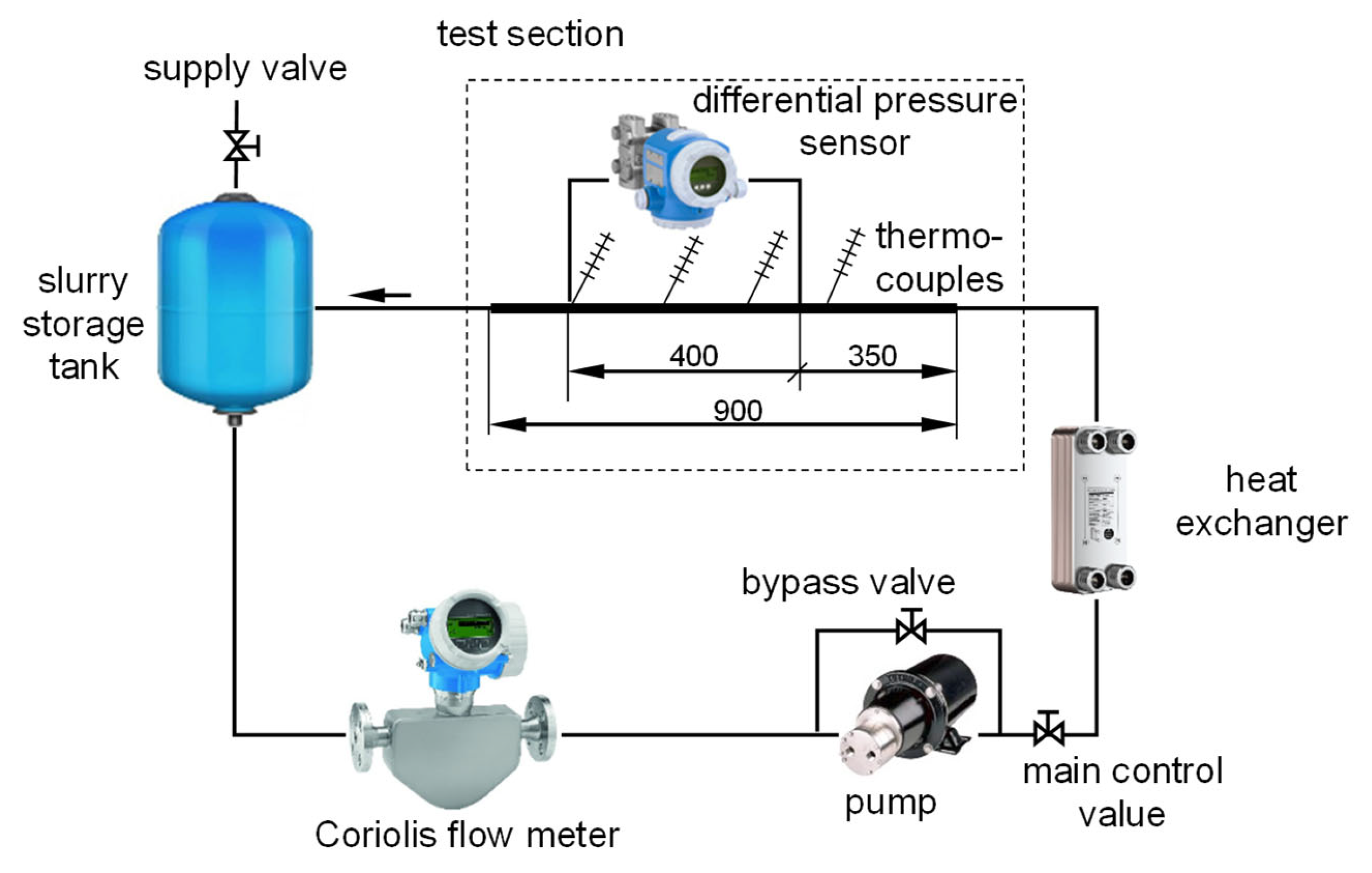

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Research Procedure and Data Calculation

3. Experimental Data

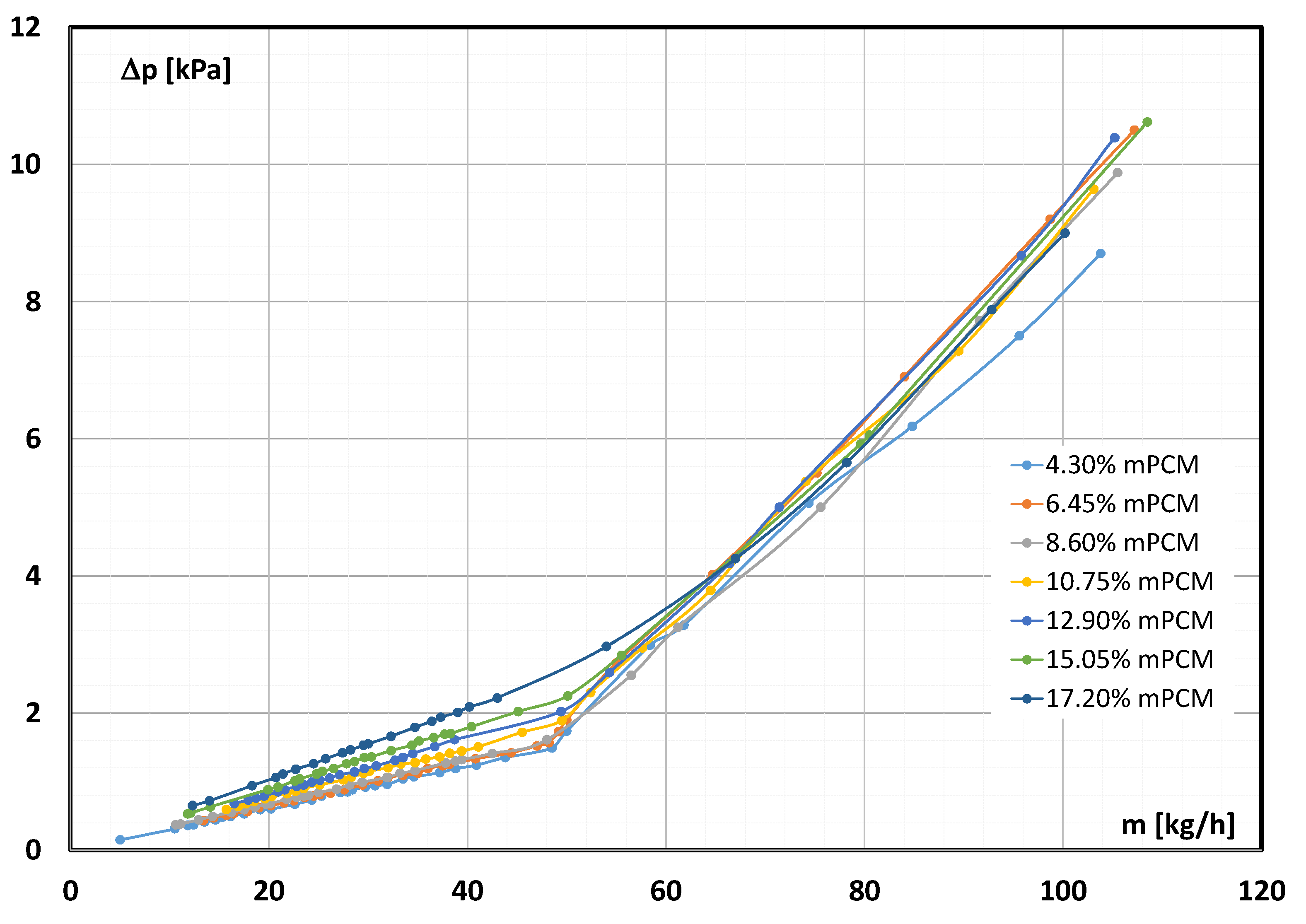

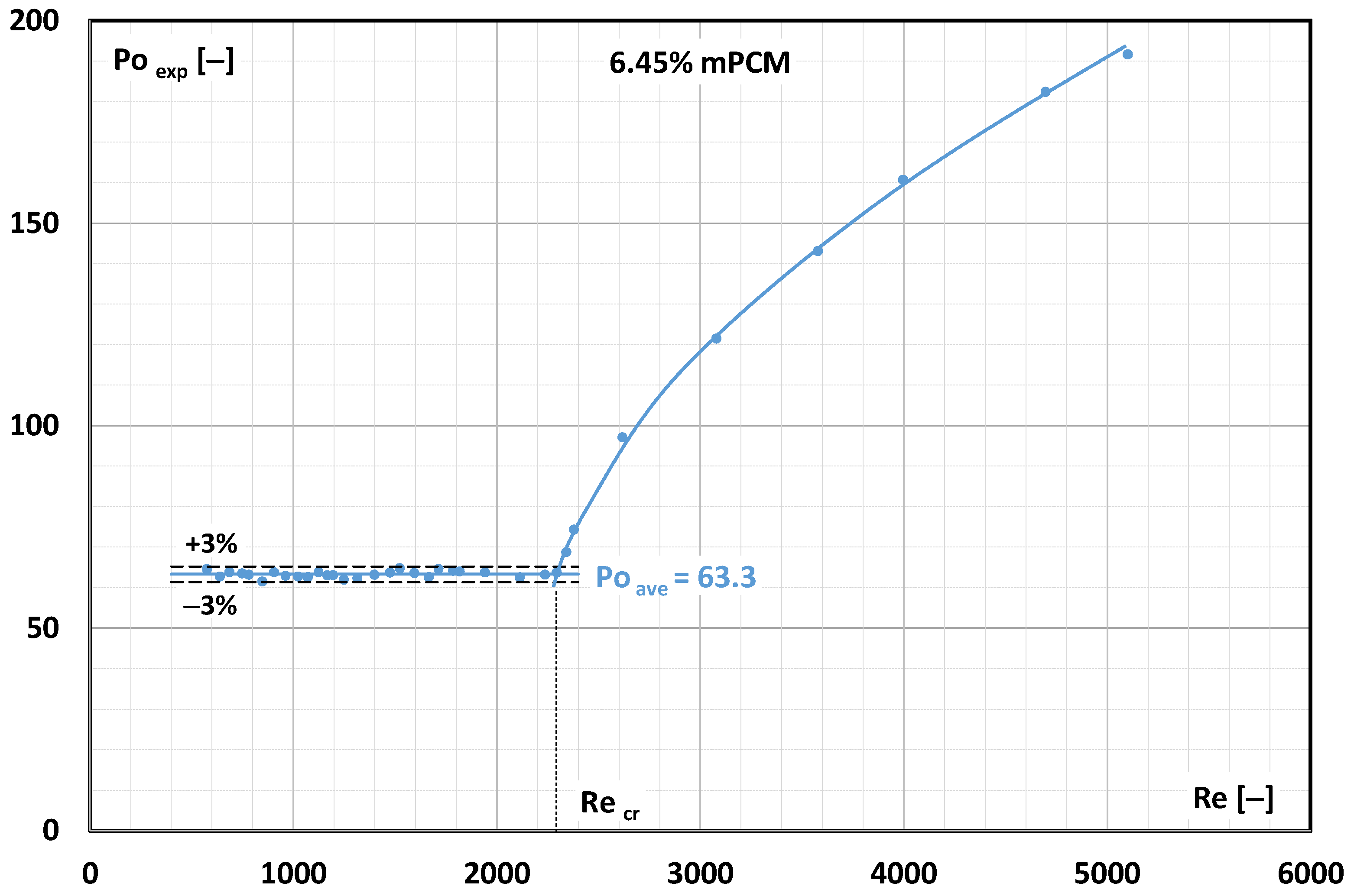

3.1. Pressure Drop in mPCM Slurry Flow

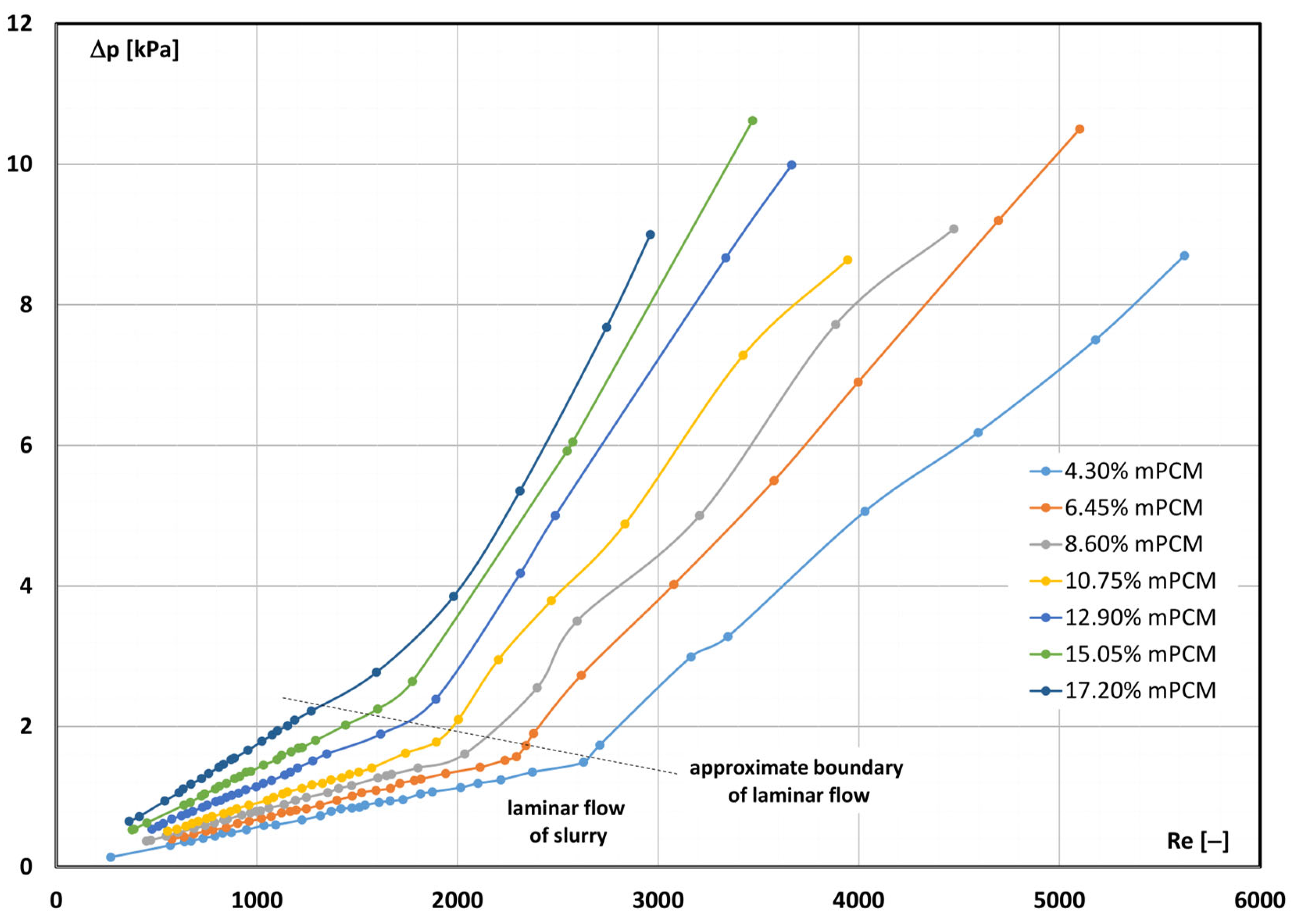

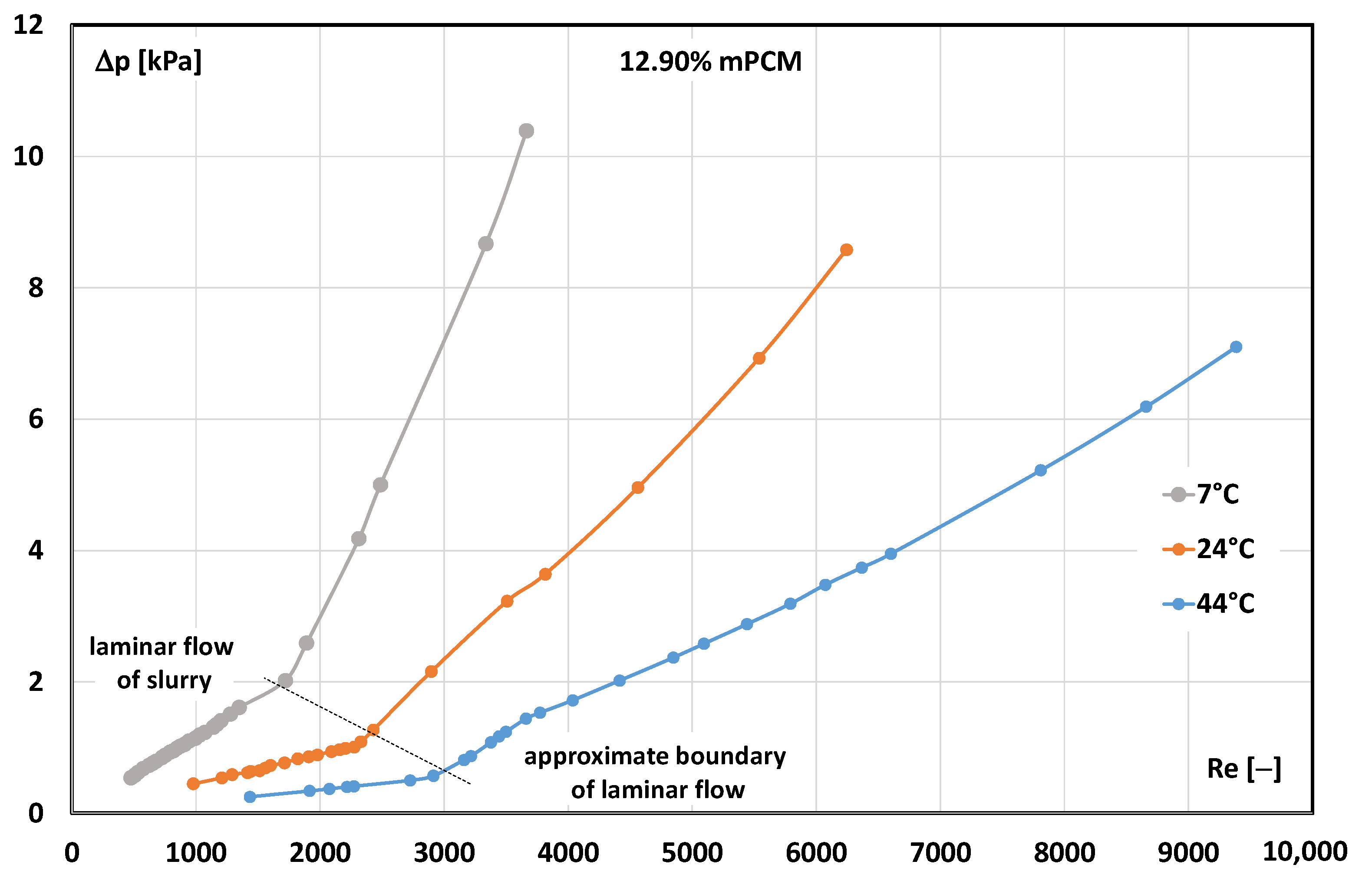

3.2. Critical Reynolds Number

4. Conclusions and Summary

- -

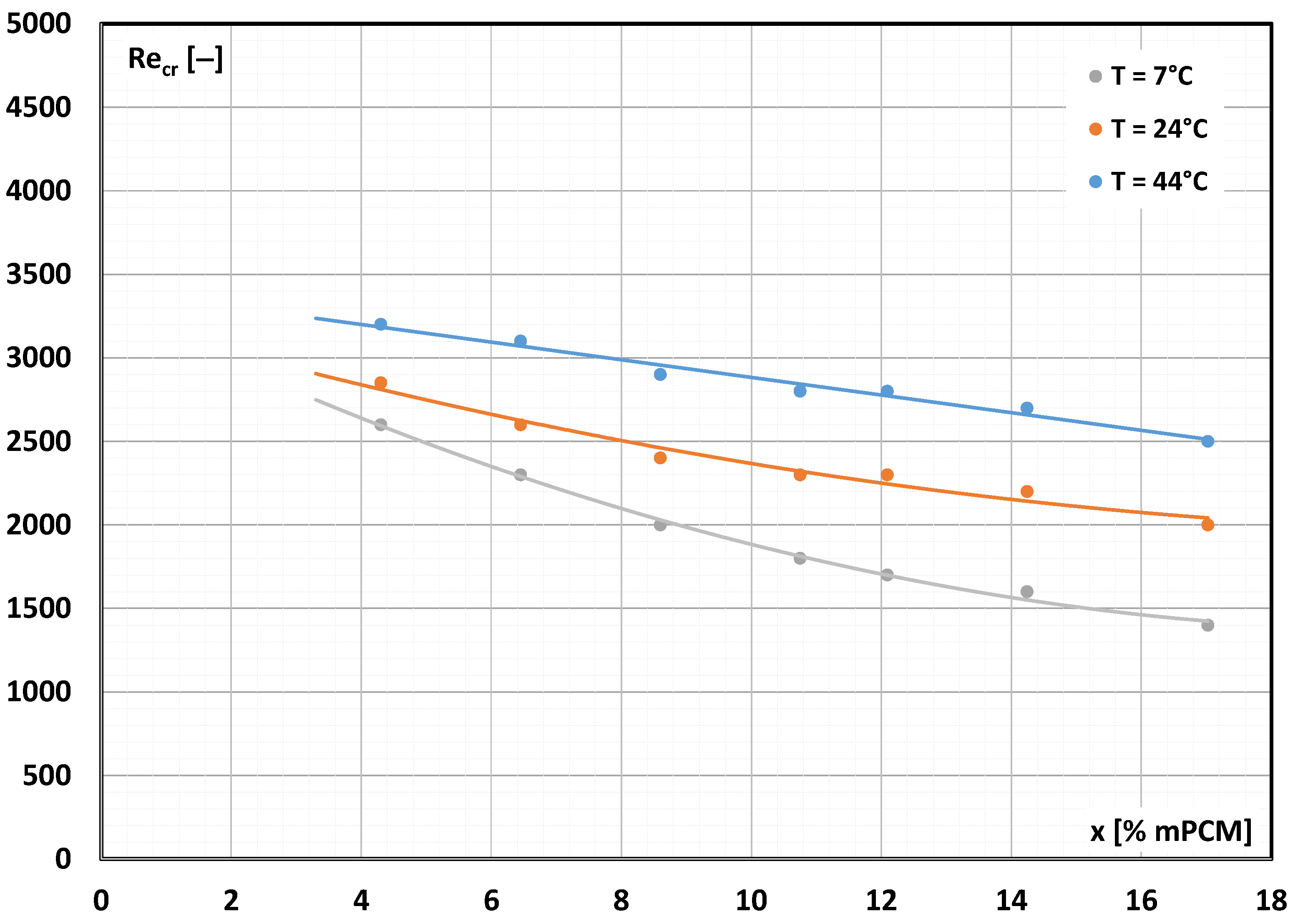

- Adding microcapsules containing PCM to the base liquid (water) affects the critical Reynolds number.

- -

- The higher the concentration of mPCM in the slurry, the more difficult it was to maintain laminar movement.

- -

- The transition from laminar to turbulent movement occurred at Re < 2300 (e.g., already at Re ≈ 1400 for 17.20% mPCM slurry at temperature T = 7 °C).

- -

- Tensile interactions between capsules filled with solid paraffin meant that the transition to turbulent flow occurred at a much lower Reynolds number than when the slurry contained microcapsules with liquid paraffin.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.W.; Wang, R.Z. An overview of phase change material slurries: MPCS and CHS. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, B.; Xiao, F. Fabrication of novel slurry containing graphene oxide-modified microencapsulated phase change material for direct absorption solar collector. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 188, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaipekli, A.; Erdoğan, T.; Barlak, S. The stability and thermophysical properties of a thermal fluid containing surface-functionalized nanoencapsulated PCM. Thermochim. Acta 2019, 682, 178406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Zhang, P. A review of thermo-fluidic performance and application of shellless phase change slurry: Part 2—Flow and heat transfer characteristics. Energy 2020, 192, 116602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Petermann, M. An experimental study on rheological behaviors of paraffin/water phase change emulsion. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 83, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, N.; Caliano, M.; Fragnito, A.; Iasiello, M.; Mauro, G.M.; Mongibello, L. Thermal analysis of micro-encapsulated phase change material (MEPCM)-based units integrated into a commercial water tank for cold thermal energy storage. Energy 2023, 266, 126479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inatsu, K.; Abe, S.; Asaoka, T. Rheological behavior of sugar alcohol slurries in horizontal circular tubes. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 128, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Kalinowski, P.; Lawler, J.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, B. Synthesis and heat transfer performance of phase change microcapsule enhanced thermal fluids. J. Heat Transf. 2015, 137, 91018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zou, D. Micro-encapsulation of a low-melting-point alloy phase change material and its application in electronic thermal management. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 138058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Wu, S.; Yao, F. Experimental Study on Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer in Rough Microchannels. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, K.; Pitchumani, R. Laminar Drag Reduction in Microchannels with Liquid Infused Textured Surfaces. 2020. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/open-access/userlicense/1.0/ (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Fiorillo, F.; Esposito, L.; Leone, G.; Pagnozzi, M. The Relationship between the Darcy and Poiseuille Laws. Water 2022, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.W.; Wang, R.Z. Experimental investigation of the hydraulic and thermal performance of a phase change material slurry in the heat exchangers. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2011, 3, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Bostanci, H.; Chow, L.C.; Hong, Y.; Wang, C.M.; Su, M.; Kizito, J.P. Heat transfer enhancement of PAO in microchannel heat exchanger using nano-encapsulated phase change indium particles. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 58, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, R.; Anwar, Z.; Imran, S.; Noor, F.; Qamar, A. Numerical Study of Heat Transfer Characteristics of mPCM Slurry During Freezing. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 7977–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Ali, S.; Tan, J. Theoretical investigation of the energy performance of a novel MPCM (Microencapsulated Phase Change Material) slurry based PV/T module. Energy 2015, 87, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.; Zou, D.; Ma, X.F.; Liu, X.S.; Hu, Z.G.; Guo, J.R.; Zhu, Y.Y. Preparation and flow resistance characteristics of novel microcapsule slurries for engine cooling system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 135, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherian, H.; Alvarado, J.L.; Tumuluri, K.; Thies, C.; Park, C.H. Fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics of microencapsulated phase change material slurry in turbulent flow. J. Heat Transf. 2014, 136, 061704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.W.; Bai, Z.Y.; Ye, J. Rheological and energy transport characteristics of a phase change material slurry. Energy 2016, 106, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.S.; Al-Shannaq, R.; Kurdi, J.; Al-Muhtaseb, S.A.; Farid, M.M. Efficacy of using slurry of metal-coated microencapsulated PCM for cooling in a micro-channel heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 122, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Experimental study on micro-encapsulated phase change material slurry flowing in straight and wavy microchannels. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 190, 116841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, K.R.; Peter, R.J.; Jinshah, B.S. Experimental investigation on paraffin encapsulated with Silica and Titanium shell in the straight and re-entrant microchannel heat sinks. Heat Mass Transf. Stoffuebertragung 2023, 59, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Peter, R.; Balasubramanian, K.R.; Ravi Kumar, K. Comparative study on the thermal performance of microencapsulated phase change material slurry in tortuous geometry microchannel heat sink. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 218, 119328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Pyatenko, A.T.; Kayukawa, N. Characteristics of Microencapsulated PCM Slurry as a Heat-Transfer Fluid. AIChE J. 1999, 45, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.J.; Chen, W.C.; Yan, W.M. Experiment on thermal performance of water-based suspensions of Al 2O3 nanoparticles and MEPCM particles in a minichannel heat sink. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 69, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.J.; Chen, W.C.; Yan, W.M. Experimental study on cooling performance of minichannel heat sink using water-based MEPCM particles. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 48, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Dammel, F.; Stephan, P.; Lin, G. Flow frictional characteristics of microencapsulated phase change material suspensions flowing through rectangular minichannels. Sci. China Ser. E Technol. Sci. 2006, 49, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H. New challenge in advanced thermal energy transportation using functionally thermal fluids. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2000, 39, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Kim, M.K.; Horibe, A. Melting heat transfer characteristics of microencapsulated phase change material slurries with plural microcapsules having different diameters. J. Heat Transf. 2004, 126, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, R.Z.; Furui, S.; Xi, G.N. Forced flow and convective melting heat transfer of clathrate hydrate slurry in tubes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 53, 3745–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Zajączkowski, B.; Białko, B. The experimental investigation of mPCM slurries density at phase change temperature. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 159, 120083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Fiuk, J.J. Experimental investigation on influence of microcapsules with PCM on propylene glycol rheological properties. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 70, 02005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Fiuk, J.J. Experimental investigation of the effects of mass fraction and temperature on the viscosity of microencapsulated PCM slurry. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 126, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Fiuk, J.J. Experimental research of viscosity of microencapsulated PCM slurry at the phase change temperature. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 134, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M. Microencapsulated PCM slurries’ dynamic viscosity experimental investigation and temperature-dependent prediction model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 145, 118741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Zajączkowski, B. Determining the heat of fusion and specific heat of microencapsulated phase change material slurry by thermal delay method. Energies 2021, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Kochanowska, M. Experimental Studies of the Pressure Drop in the Flow of a Microencapsulated Phase-Change Material Slurry in the Range of the Critical Reynolds Number. Energies 2023, 16, 6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkowski, K. Experimental investigations of Poiseuille number laminar flow of water and air in minichannels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 5983–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Equipment | Range | Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| Mass flow meter | 0–110 kg/h | ±0.2% of the measured value |

| Differential pressure sensor | 0–50 kPa | ±0.075% of the maximum value (±37.5 Pa) |

| K-type thermocouples | −40 °C–+475 °C | ±0.2 K |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dutkowski, K.; Kruzel, M.; Kochanowska, M. Transition Boundary from Laminar to Turbulent Flow of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Slurry—Experimental Results. Materials 2024, 17, 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17246041

Dutkowski K, Kruzel M, Kochanowska M. Transition Boundary from Laminar to Turbulent Flow of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Slurry—Experimental Results. Materials. 2024; 17(24):6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17246041

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutkowski, Krzysztof, Marcin Kruzel, and Martyna Kochanowska. 2024. "Transition Boundary from Laminar to Turbulent Flow of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Slurry—Experimental Results" Materials 17, no. 24: 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17246041

APA StyleDutkowski, K., Kruzel, M., & Kochanowska, M. (2024). Transition Boundary from Laminar to Turbulent Flow of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Slurry—Experimental Results. Materials, 17(24), 6041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17246041