Growth of Oxide and Nitride Layers on Titanium Foil and Their Electrochemical Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results

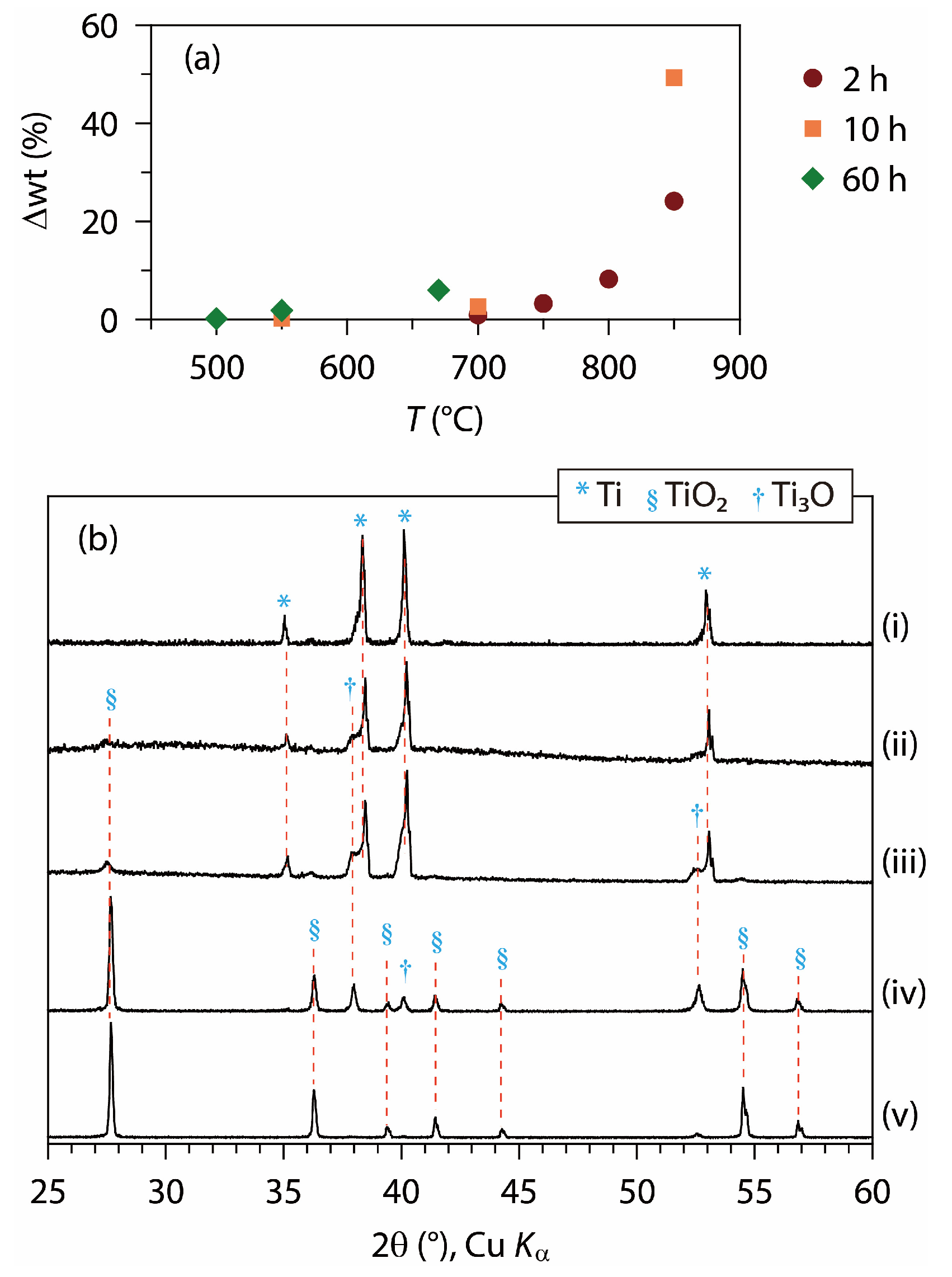

3.1. Formations of Titanium Dioxide and Suboxide Coatings

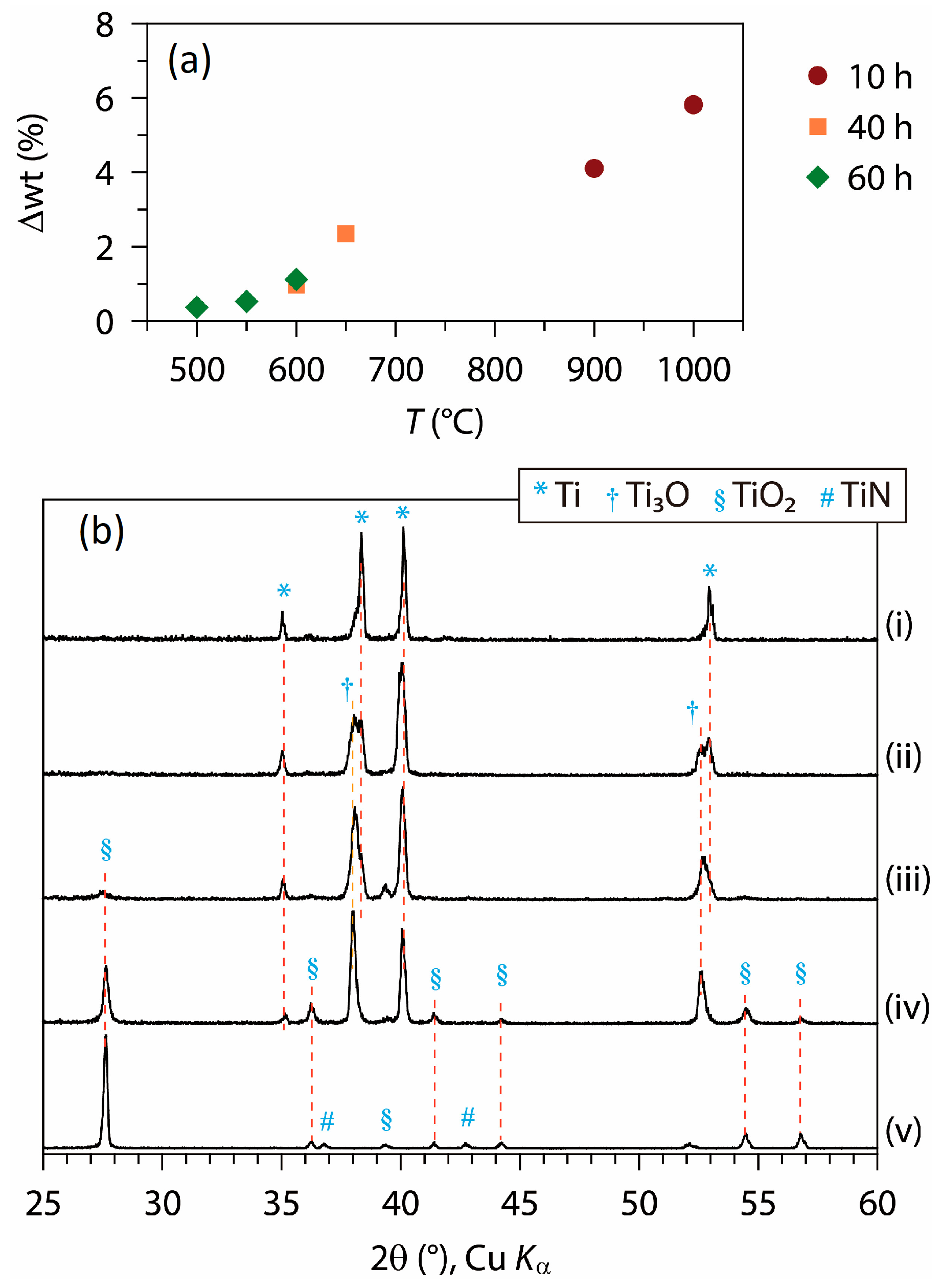

3.2. Formations of Titanium Nitride Coatings

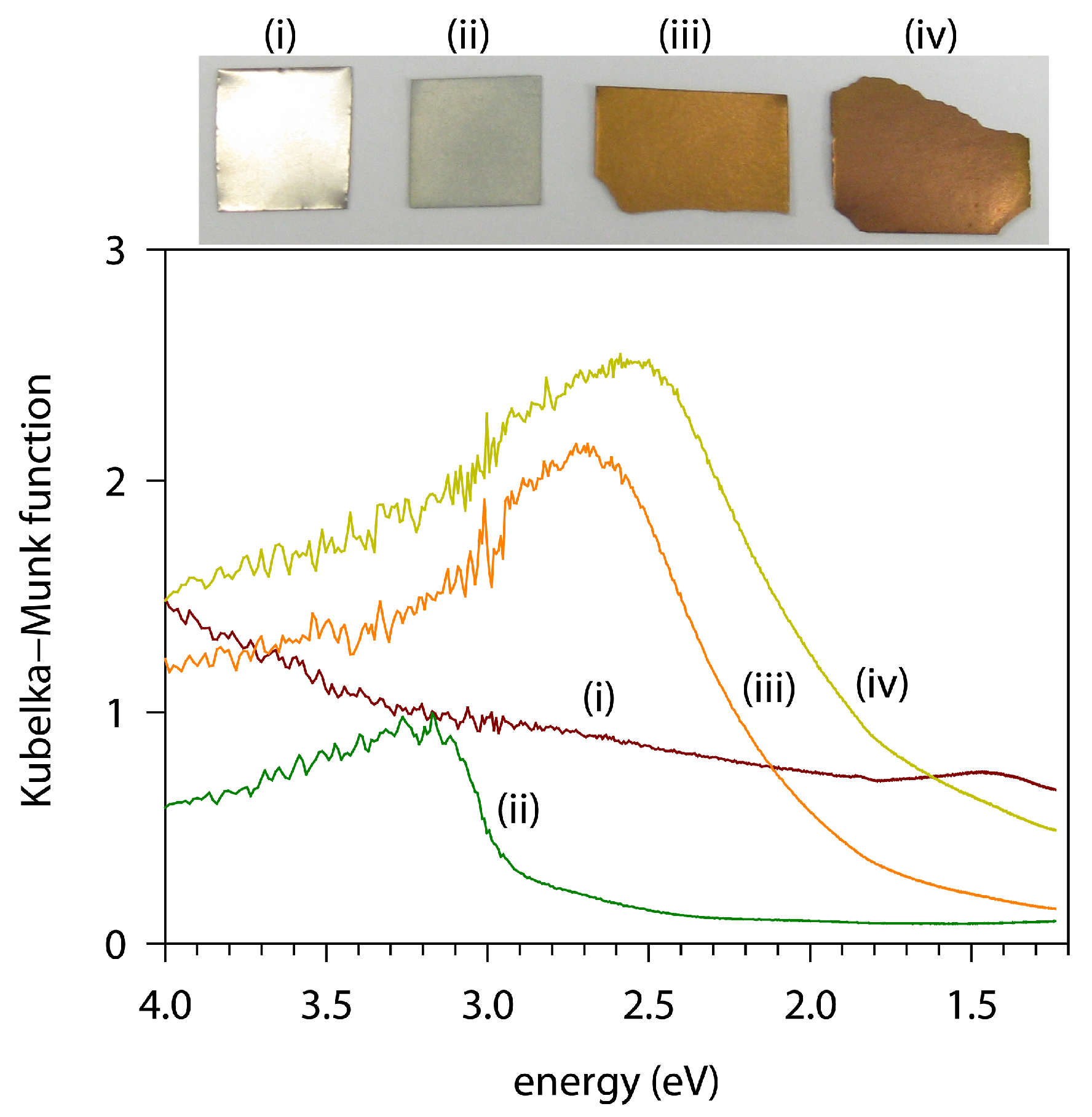

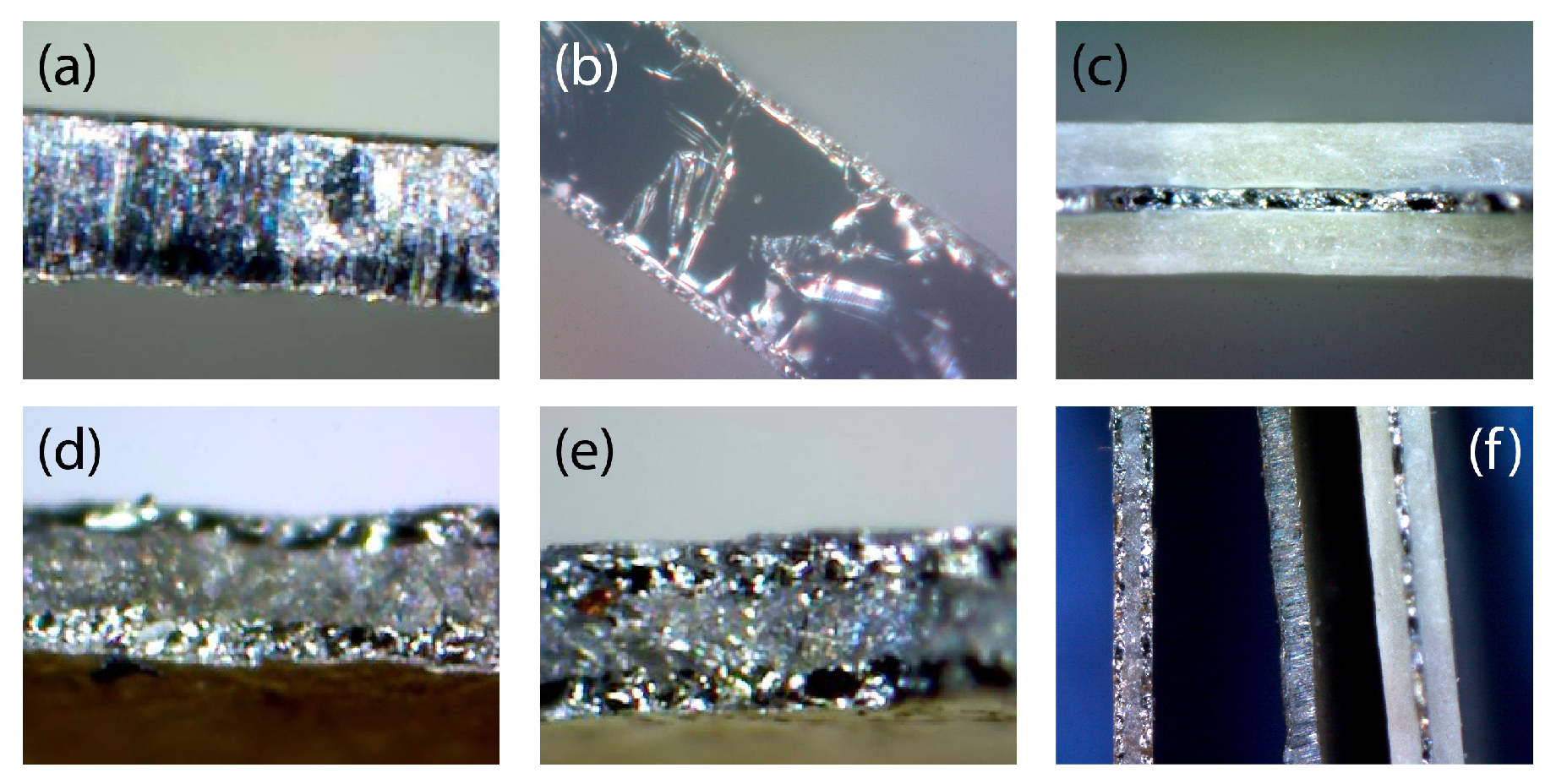

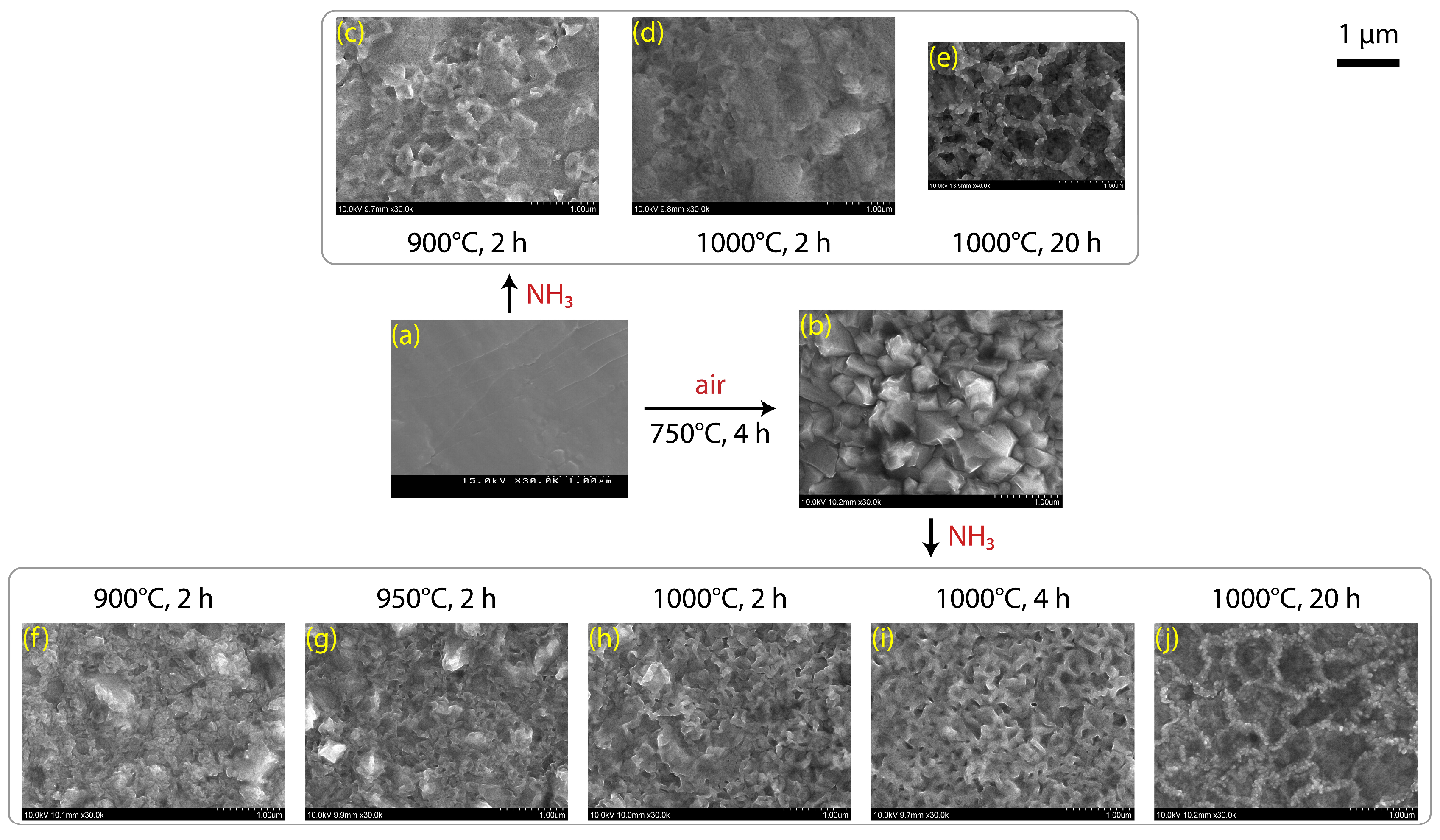

3.3. Microscopic Images and Optical Properties

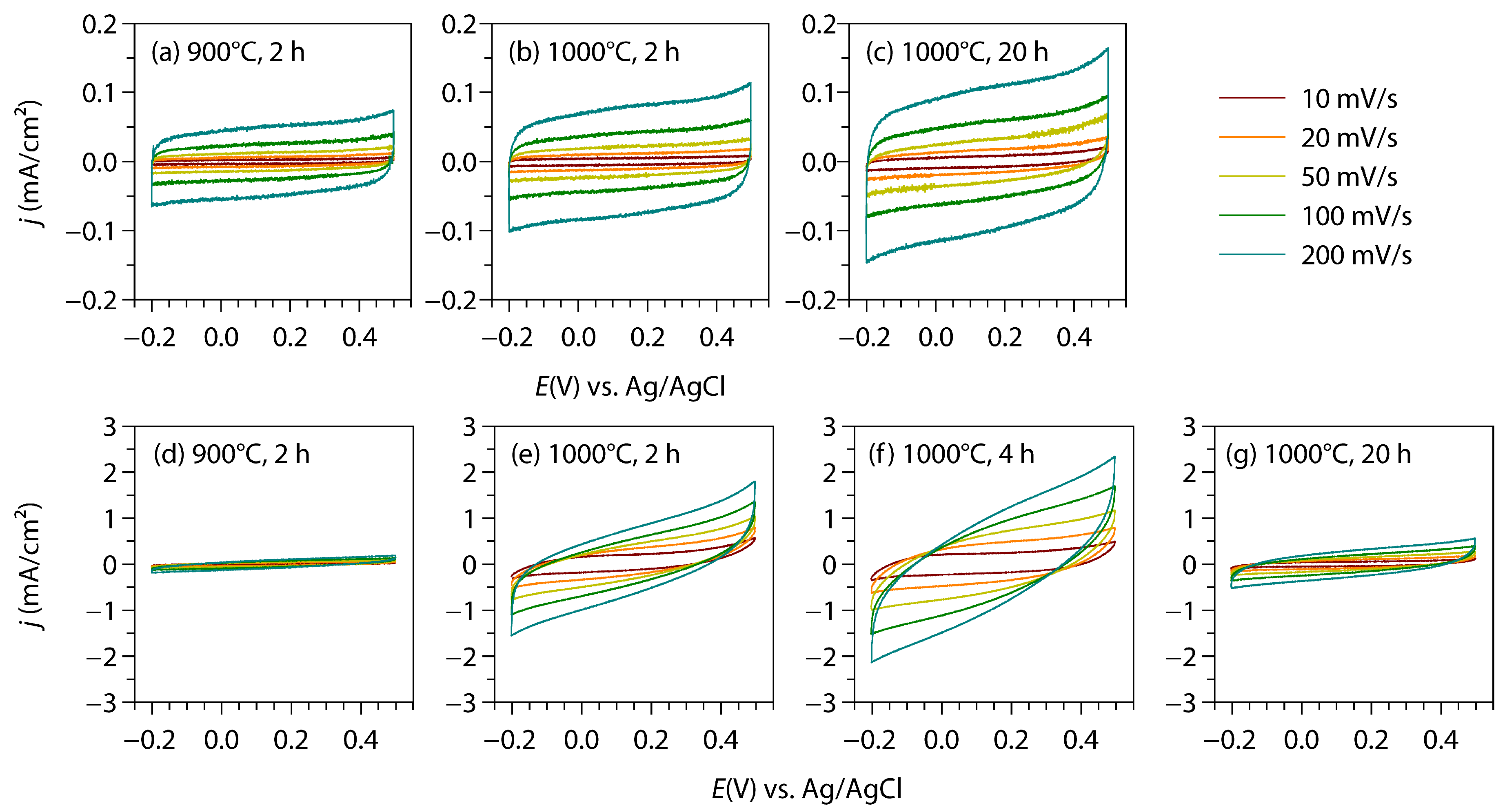

3.4. Electrochemical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hiroi, Z. Inorganic structural chemistry of titanium dioxide polymorphs. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 8393–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranade, M.R.; Navrotsky, A.; Zhang, H.Z.; Banfield, J.F.; Elder, S.H.; Zaban, A.; Borse, P.H.; Kulkarni, S.K.; Doran, G.S.; Whitfield, H.J. Energetics of nanocrystalline TiO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6476–6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Collen, B.; Kuylenstierna, U.; Magneli, A. Phase analysis studies on the titanium-oxygen system. Acta Chem. Scand. 1957, 11, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. A review: Synthesis and applications of titanium sub-oxides. Materials 2023, 16, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanavicius, S.; Jagminas, A. Synthesis, characterisation, and applications of TiO and other black titania nanostructures species (review). Crystals 2024, 14, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Barbhuiya, N.H.; Singh, S.P. Magnéli phase titanium sub-oxides synthesis, fabrication and its application for environmental remediation: Current status and prospect. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Sohn, H.Y.; Mohassab, Y.; Lan, Y. Structures, preparation and applications of titanium suboxides. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 79706–79722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayashree, S.; Ashokkumar, M. Switchable intrinsic defect chemistry of titania for catalytic applications. Catalysts 2018, 8, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jostsons, A.; Malin, A.S. The ordered structure of Ti3O. Acta Crystallogr. B 1968, 24, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Koiwa, M.; Hirabayashi, M. Interstitial superlattice of Ti6O and its transformation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1966, 21, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S. Interstitial order-disorder transformation in the Ti-O solid solution. I. Ordered arrangement of oxygen. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1969, 27, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-C.; Goto, T.; Hirai, T. Non-stoichiometry of titanium nitride plates prepared by chemical vapour deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 1993, 190, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zeng, Q.; Oganov, A.R.; Frapper, G.; Zhang, L. Phase stability, chemical bonding and mechanical properties of titanium nitrides: A first-principles study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 11763–11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengauer, W. The titanium-nitrogen system: A study of phase reactions in the subnitride region by means of diffusion couples. Acta Metall. Mater. 1991, 39, 2985–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, A.; Debuigne, J. Oxynitruration du titane sous basses pressions d’air sec a hautes temperatures. J. Less-Common Met. 1988, 142, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengauer, W. Properties of bulk δ-TiN1−x prepared by nitrogen diffusion into titanium metal. J. Alloys Compd. 1992, 186, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.H.; Bugli, G.; Djega-Mariadassou, G. Preparation and characterization of titanium oxynitrides with high specific surface areas. J. Solid State Chem. 1991, 95, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.-Q.; Zhao, X.-R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.-J.; Wu, D.; Li, A.-D. TiOxNy modified TiO2 powders prepared by plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition for highly visible light photocatalysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mao, S.S. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2891–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anucha, C.B.; Altin, I.; Bacaksiz, E.; Stathopoulos, V.N. Titanium dioxide (TiO2)-based photocatalyst materials activity enhancement for contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) degradation: In the light of modification strategies. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 10, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Misu, S.; Hirayama, J.; Otomo, R.; Kamiya, Y. Magneli-phase titanium suboxide nanocrystals as highly active catalysts for selective acetalization of furfural. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, W. TiN coating of tool steels: A review. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1993, 39, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, H.; Mazaki, N.; Takahashi, M.; Watanabe, T.; Yang, X.; Aizawa, T. Mechanical properties of bulk sintered titanium nitride ceramics. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 319–321, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Das, M.; Balla, V.K.; Bodhak, S.; Murugesan, V.K. Mechanical, wear, corrosion and biological properties of arc deposited titanium nitride coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 344, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, G.; Kitada, A.; Kawasaki, S.; Kanamori, K.; Nakanishi, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kageyama, H.; Abe, T. Impact of electrolyte on pseudocapacitance and stability of porous titanium nitride (TiN) monolithic electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A77–A85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Kumta, P.N. Nanocrystalline TiN derived by a two-step halide approach for electrochemical capacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A2298–A2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brat, T.; Parikh, N.; Tsai, N.S.; Sinha, A.K.; Poole, J.; Wickersham, C. Characterization of titanium nitride films sputter deposited from a high-purity titanium nitride target. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 1987, 5, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, M.P.; Quach, T.-A.; Urupalli, B.; Kumar, S.; Fu, Y.-P.; Murikinati, M.K.; Venkatakrishnan, S.M.; Do, T.-O.; Mohan, S. Phase engineering of titanium oxynitride system and its solar light-driven photocatalytic dye degradation, H2 generation, and N2 fixation properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 15192–15206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, N.R.; Som, J.; Choi, J.; Shaji, S.; Gupta, R.K.; Meyer, H.M.; Cramer, C.L.; Elliott, A.M.; Kumar, D. High-performance titanium oxynitride thin films for electrocatalytic water oxidation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 8366–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, U.; Dhonde, M.; Sahu, K.; Ghoshc, P.; Shirage, P.M. Titanium nitride (TiN) as a promising alternative to plasmonic metals: A comprehensive review of synthesis and applications. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 846–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.N.; Ghosh, S.; Thomas, T. Metal oxynitrides as promising electrode materials for supercapacitor applications. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 1255–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Chao, D.; Zhu, C.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, P.; Tay, B.K.; Shen, Z.X.; Mai, W.; et al. Ultrafast-charging supercapacitors based on corn-like titanium nitride nanostructures. Adv. Sci. 2015, 3, 1500299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, S.A.; Khan, N.A.; Hasan, Z.; Shaikh, A.A.; Ferdousi, F.K.; Barai, H.R.; Lopa, N.S.; Rahman, M.M. Electrochemical synthesis of titanium nitride nanoparticles onto titanium foil for electrochemical supercapacitors with ultrafast charge/discharge. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 2480–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B.M.; Hector, A.L.; Jura, M.; Owen, J.R.; Whittam, J. Effect of oxidative surface treatments on charge storage at titanium nitride surfaces for supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 4550–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, G.; Tan, S.; Zhou, M.; Zou, G.; Deng, S.; Smirnov, S.; Luo, H. Titanium oxynitride nanoparticles anchored on carbon nanotubes as energy storage materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 24212–24217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Du, X.; Li, X.; Ma, M.; Xiong, L. Ultrahigh-areal capacitance flexible supercapacitors based on laser assisted construction of hierarchical aligned carbon nanotubes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Ma, X.; Su, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, D. TiN thin film electrodes on textured silicon substrates for supercapacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, H802–H809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, T.; Chen, J.; Su, L. Tunable preparation of chrysanthemum-like titanium nitride as flexible electrode materials for ultrafast-charging/discharging and excellent stable supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2018, 396, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Rosero-Navarro, C.; Masubuchi, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Kikkawa, S.; Tadanaga, K. Nitrogen-rich manganese oxynitrides with enhanced catalytic activity in the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7963–7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Chen, X.; Gu, L.; Zhou, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Han, P.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Facile preparation of mesoporous titanium nitride microspheres for electrochemical energy storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Feng, J.; Yan, S.; Luo, W.; Liu, J.; Yu, T.; Zou, Z. MnO2 nanolayers on highly conductive TiO0.54N0.46 nanotubes for supercapacitor electrodes with high power density and cyclic stability. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 8521–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achour, A.; Porto, R.L.; Soussou, M.-A.; Islam, M.; Boujtita, M.; Aissa, K.A.; Le Brizoual, L.; Djouadi, A.; Brousse, T. Titanium nitride films for micro-supercapacitors: Effect of surface chemistry and film morphology on the capacitance. J. Power Sources 2015, 300, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Fieandt, L.; Larsson, T.; Lindahl, E.; Backe, O.; Boman, M. Chemical vapor deposition of TiN on transition metal substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 334, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafizas, A.; Carmalt, C.J.; Parkin, I.P. CVD and precursor chemistry of transition metal nitrides. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2073–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Hwang, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, S.W. Alternative surface reaction route in the atomic layer deposition of titanium nitride thin films for electrode applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brihmat-Hamadi, F.; Amara, E.H.; Kellou, H. Characterization of titanium oxide layers formation produced by nanosecond laser coloration. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2017, 48, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.R.; Deshpande, V.T. The anisotropy of the thermal expansion of α-titanium. Acta Crystallogr. A 1968, 24, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesenhues, U.; Rentschler, T. Crystal growth and defect structure of Al3+-doped rutile. J. Solid State Chem. 1999, 143, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, R.; Laurent, Y.; Guyader, J.; L’Haridon, P.; Verdier, P. Nitrides and oxynitrides: Preparation, crystal chemistry and properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 8, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Ng, W.; McMurdie, H.F.; Paretzkin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Davis, K.L.; Hubbard, C.R.; Dragoo, A.L.; Stewart, J.M. Standard X-ray diffraction powder patterns of sixteen ceramic phases. Powder Diffr. 1987, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenguaer, W.; Ettmayer, P. Investigations of phase equilibria in the Ti-N and Ti-Mo-N systems. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1988, 105–106, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, B.; Yhland, M.; Dahlbom, R.; Sjovall, J.; Theander, O.; Flood, H. Structural studies on the titanium-nitrogen system. Acta Chem. Scand. 1962, 16, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P.; Munk, F. Ein beitrag zur optic der farbanstriche. Z. Tech. Phys. 1931, 12, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zou, Z. Application of binder-free TiOxN1−x nanogrid film as a high-power supercapacitor electrode. J. Power Sources 2015, 296, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Li, X.; Gao, B.; Fu, J.; Xia, L.; Zhang, X.; Huo, K.; Shen, W.; Chu, P.K. Hierarchical TiN nanoparticles-assembled nanopillars for flexible supercapacitors with high volumetric capacitance. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 8728–8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Wang, G.; Zhai, T.; Yu, M.; Xie, S.; Ling, Y.; Liang, C.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Stabilized TiN Nanowire Arrays for High-Performance and Flexible Supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 5376–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Liang, H.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Z.; Shen, H.; Wang, Z. Magnetron sputtered TiN thin films toward enhanced performance supercapacitor electrodes. Mater. Renew. Sustain. 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, A.; Ducros, J.B.; Porto, R.L.; Boujtita, M.; Gautron, E.; Le Brizoual, L.; Djouadi, M.A.; Brousse, T. Hierarchical nanocomposite electrodes based on titanium nitride and carbon nanotubes for micro-supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2014, 7, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, E.; Yang, C.; Warren, R.; Kozinda, A.; Lin, L. ALD titanium nitride coated carbon nanotube electrodes for electrochemical supercapacitors. In Proceedings of the 2015 Transducers-2015 18th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), Anchorage, AK, USA, 21–25 June 2015; pp. 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, H. Electrochemical capacitance performance of titanium nitride nanoarray. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2013, 178, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Ming, F.; Liang, H.; Qi, Z.; Hu, W.; Wang, Z. All nitride asymmetric supercapacitors of niobium titanium nitride-vanadium nitride. J. Power Sources 2021, 481, 228842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Tian, F. Capacitive performance of molybdenum nitride/titanium nitride nanotube array for supercapacitor. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2017, 215, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CV | GCD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (mV/s) | Cs (mF/cm2) | j (mA/cm2) | Cs (mF/cm2) |

| 10 | 37.0 | 0.034 | 66.2 |

| 50 | 19.6 | 0.045 | 57.7 |

| 100 | 13.0 | 0.113 | 29.8 |

| 200 | 9.0 | 0.340 | 17.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.-I. Growth of Oxide and Nitride Layers on Titanium Foil and Their Electrochemical Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18020380

Kim SH, Kim Y-I. Growth of Oxide and Nitride Layers on Titanium Foil and Their Electrochemical Properties. Materials. 2025; 18(2):380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18020380

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Song Hyeon, and Young-Il Kim. 2025. "Growth of Oxide and Nitride Layers on Titanium Foil and Their Electrochemical Properties" Materials 18, no. 2: 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18020380

APA StyleKim, S. H., & Kim, Y.-I. (2025). Growth of Oxide and Nitride Layers on Titanium Foil and Their Electrochemical Properties. Materials, 18(2), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18020380