Electrochemical Corrosion Properties and Protective Performance of Coatings Electrodeposited from Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Electrolytes: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Electrochemical Corrosion Characteristics and Protective Performance of Coatings

2.1. Corrosion Resistance and Protective Properties of Zinc-Based Coatings

2.2. Corrosion Resistance and Protective Properties of Nickel-Based Coatings

2.3. Corrosion Resistance and Protective Properties of Chromium-Based Coatings

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chung, P.P.; Wang, J.; Durandet, Y. Deposition processes and properties of coatings on steel fasteners—A review. Friction 2019, 7, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A.; Blanpain, B.; Wouters, G.; Celis, J.P.; Roos, J. Electrochemical deposition: A method for the production of artificially structured materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1993, 168, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovvati, B.; Namdari, N.; Dehghanghadikolaei, A. On coating techniques for surface protection: A review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process 2019, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrasti, P.; Ponce de León, C.; Walsh, F.C. The corrosion behaviour of nanograined metals and alloys. Rev. Metal. 2012, 48, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrappa, I.; Binder, L. Electrodeposition of nanostructured coatings and their characterization—A review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008, 9, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, M.S.; Pushpavanam, M. Pulse and pulse reverse plating—Conceptual, advantages and applications. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 3313–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z. Coatings. In Principles of Corrosion Engineering and Corrosion Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Chapter 7; pp. 382–437. [Google Scholar]

- Aliofkhazraei, M.; Walsh, F.C.; Zangari, G.; Köçkar, H.; Alper, M.; Rizal, C.; Magagnin, L.; Protsenko, V.; Arunachalam, R.; Rezvanian, A.; et al. Development of electrodeposited multilayer coatings: A review of fabrication, microstructure, properties and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Danilov, F.I. The corrosion-protective traits of electroplated multilayer zinc-iron-chromium deposits. Metal Finish. 2010, 108, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kityk, A.; Pavlik, V.; Hnatko, M. Breaking barriers in electrodeposition: Novel eco-friendly approach based on utilization of deep eutectic solvents. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 334, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11060–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep eutectic solvents: A review of fundamentals and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the nature of eutectic and deep eutectic mixtures. J. Solut. Chem. 2019, 48, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tome, L.I.N.; Baiao, V.; da Silva, W.; Brett, C.M.A. Deep eutectic solvents for the production and application of new materials. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 10, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S.; König, U. Electrofinishing of metals using eutectic based ionic liquids. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 2008, 86, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.G.d.R.d.; Costa, J.M.; Almeida Neto, A.F.d. Progress on electrodeposition of metals and alloys using ionic liquids as electrolytes. Metals 2022, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, N.N.; Do, H.D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L.; Lee, N.Y. Design strategy and application of deep eutectic solvents for green synthesis of nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashu, S.; Khan, R. Recent work on electrochemical deposition of Zn-Ni(-X) alloys for corrosion protection of steel. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2019, 66, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, N.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Rahmani, H.; Darband, G.B. Zinc–nickel alloy electrodeposition: Characterization, properties, multilayers and composites. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2018, 54, 1102–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniam, K.K.; Paul, S. Progress in electrodeposition of zinc and zinc nickel alloys using ionic liquids. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.H.; Pölzler, M.; Gollas, B. Zinc electrodeposition from a deep eutectic system containing choline chloride and ethylene glycol. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, D328–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starykevich, M.; Salak, A.N.; Ivanou, D.K.; Lisenkov, A.D.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Electrochemical deposition of zinc from deep eutectic solvent on barrier alumina layers. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 170, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.; Schennach, R.; Gollas, B. The effect of the electrode material on the electrodeposition of zinc from deep eutectic solvents. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 197, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Reddy, R.G. Electrochemical deposition of zinc from zinc oxide in 2:1 urea/choline chloride ionic liquid. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 147, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Liu, B.; Peng, Z. Preparation of superhydrophobic zinc coating for corrosion protection. Colloids Surf. A 2014, 454, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Barron, J.C.; Frisch, G.; Ryder, K.S.; Silva, A.F. The effect of additives on zinc electrodeposition from deep eutectic solvents. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 5272–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesary, H.F.; Cihangir, S.; Ballantyne, A.D.; Harris, R.C.; Weston, D.P.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Influence of additives on the electrodeposition of zinc from a deep eutectic solvent. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 304, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

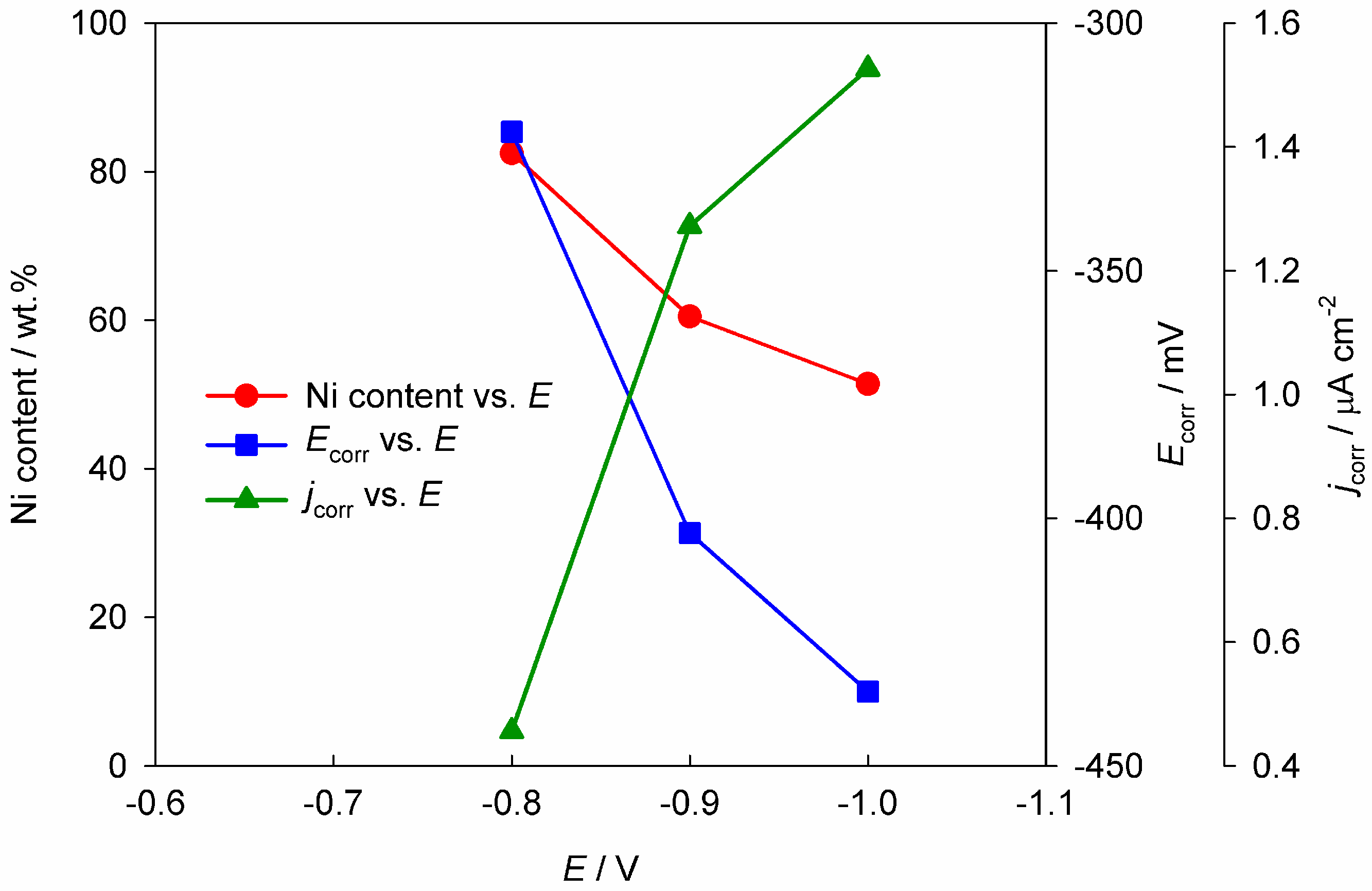

- Fashu, S.; Gu, C.D.; Wang, X.L.; Tu, J.P. Influence of electrodeposition conditions on the microstructure and corrosion resistance of Zn–Ni alloy coatings from a deep eutectic solvent. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 242, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Dong, Q.; Xia, J.; Luo, C.; Sheng, L.; Cheng, F.; Liang, J. Electrodeposition of composition controllable Zn–Ni coating from water modified deep eutectic solvent. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 366, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Alesary, H.F.; Khan, F.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S. Gamma-phase Zn-Ni alloy deposition by pulse-electroplating from a modified deep eutectic solution. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 403, 126434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

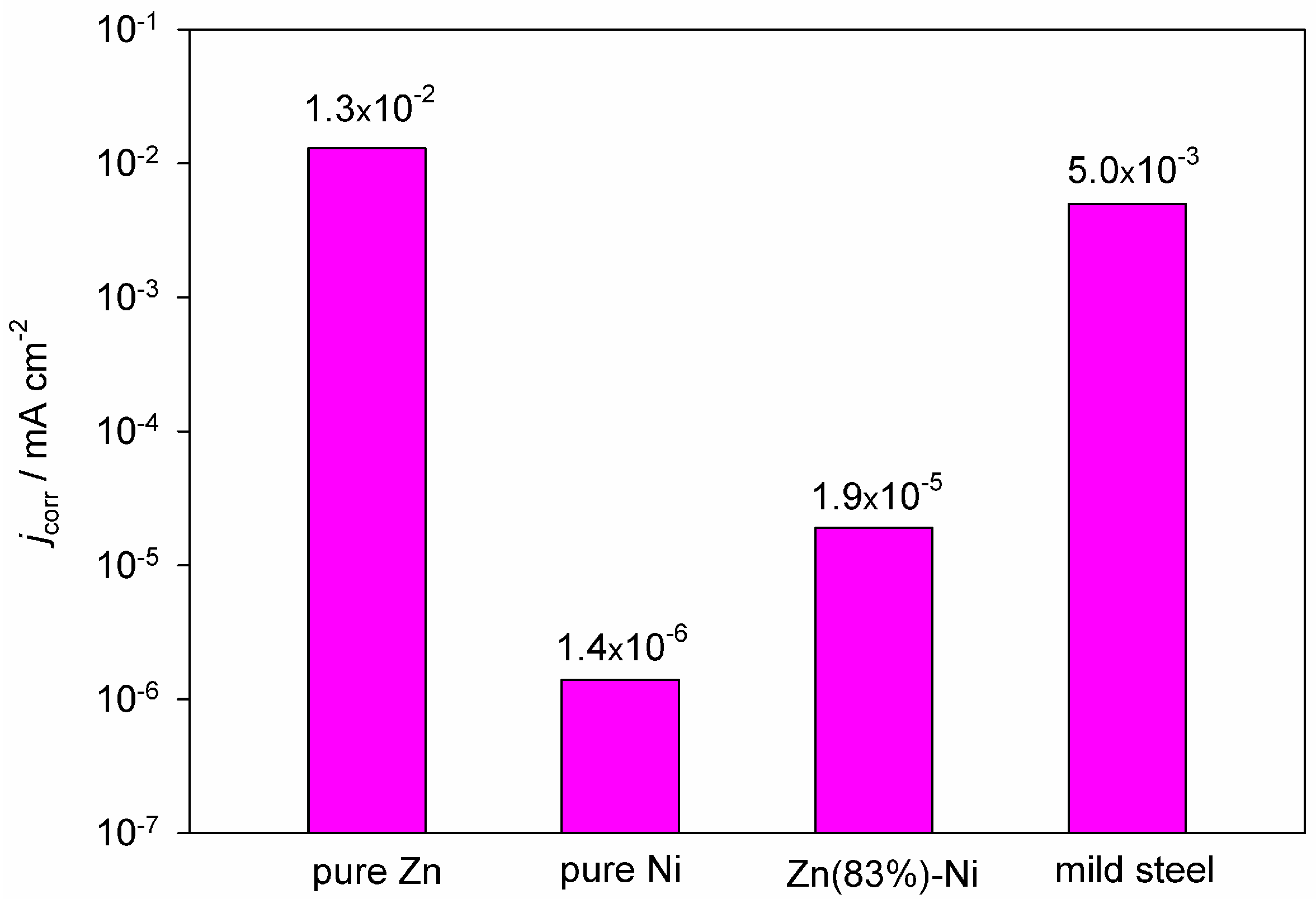

- Bernasconi, R.; Panzeri, G.; Firtin, G.; Kahyaoglu, B.; Nobili, L.; Magagnin, L. Electrodeposition of ZnNi alloys from choline chloride/ethylene glycol deep eutectic solvent and pure ethylene glycol for corrosion protection. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 10739–10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Skouby, H.; Kellner, R.; Goosey, E.; Goosey, M.; Sellars, J.; Elliott, D.; Ryder, K.S. Barrel electroplating of Zn-Ni alloy coatings from a modified deep eutectic solvent. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 2022, 100, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesary, H.F.; Ismail, H.K.; Shiltagh, N.M.; Alattar, R.A.; Ahmed, L.M.; Watkins, M.J.; Ryder, K.S. Effects of additives on the electrodeposition of ZnSn alloys from choline chloride/ethylene glycol-based deep eutectic solvent. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 874, 114517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučko, M.; Tomić, M.V.; Maksimović, M.; Bajat, J.B. The importance of using hydrogen evolution inhibitor during the Zn and Zn–Mn electrodeposition from ethaline. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2019, 84, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.C.; Larson, C. Towards improved electroplating of metal-particle composite coatings. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 2020, 98, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sánchez, M.; Gracia-Escosa, E.; Conde, A.; Palacio, C.; García, I. Deposition of zinc–cerium coatings from deep eutectic ionic liquids. Materials 2018, 11, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Q.; Liang, J.; Hao, J. Electrodeposition of zinc-cobalt alloys from choline chloride–ureaionic liquid. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 115, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, Q.; Hua, Y.; Li, J. The electrodeposition of Zn-Ti alloys from ZnCl2-urea deep eutectic solvent. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014, 18, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, B.O.; Jeong, C.; Jang, C. Advances on Cr and Ni electrodeposition for industrial applications—A review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriňáková, R.; Turoňová, A.; Kladeková, D.; Gálová, M.; Smith, R.M. Recent developments in the electrodeposition of nickel and some nickel-based alloys. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2006, 36, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, U.S.; Tripathy, B.C.; Singh, P.; Keshavarz, A.; Iglauer, S. Roles of organic and inorganic additives on the surface quality, morphology, and polarization behavior during nickel electrodeposition from various baths: A review. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 49, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabinejad, V.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Assareh, S.; Allahyarzadeh, M.H.; Rouhaghdam, A.S. Electrodeposition of Ni-Fe alloys, composites, and nano coatings—A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 691, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niciejewska, A.; Ajmal, A.; Pawlyta, M.; Marczewski, M.; Winiarski, J. Electrodeposition of Ni–Mo alloy coatings from choline chloride and propylene glycol deep eutectic solvent plating bath. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilov, F.I.; Bogdanov, D.A.; Smyrnova, O.V.; Korniy, S.A.; Protsenko, V.S. Electrodeposition of Ni–Fe alloy from a choline chloride-containing ionic liquid. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; El Ttaib, K.; Ryder, K.S.; Smith, E.L. Electrodeposition of nickel using eutectic based ionic liquids. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 2008, 86, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.D.; You, Y.H.; Yu, Y.L.; Qu, S.X.; Tu, J.P. Microstructure, nanoindentation, and electrochemical properties of the nanocrystalline nickel film electrodeposited from choline chloride–ethylene glycol. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 4928–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Tu, J. One-step fabrication of nanostructured Ni film with Lotus effect from deep eutectic solvent. Langmuir 2011, 27, 10132–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Ballantyne, A.; Harris, R.C.; Juma, J.A.; Ryder, K.S.; Forrest, G. A comparative study of nickel electrodeposition using deep eutectic solvents and aqueous solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, R.; Magagnin, L. Electrodeposition of nickel from DES on aluminium for corrosion protection. Surf. Eng. 2017, 33, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, F.I.; Protsenko, V.S.; Kityk, A.A.; Shaiderov, D.A.; Vasil’eva, E.A.; Pramod Kumar, U.; Joseph Kennady, C. Electrodeposition of nanocrystalline nickel coatings from a deep eutectic solvent with water addition. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2017, 53, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

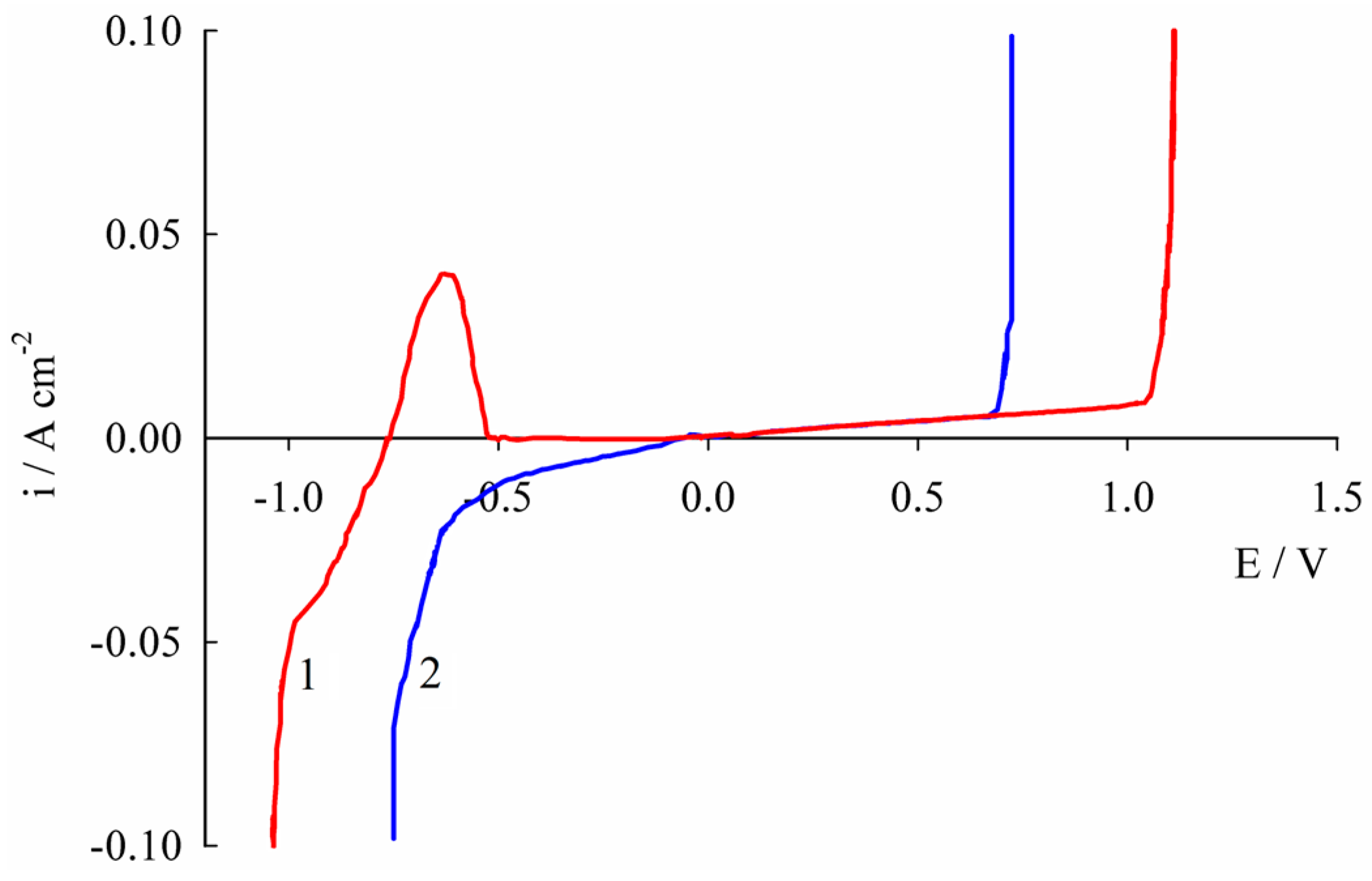

- Protsenko, V.S.; Kityk, A.A.; Shaiderov, D.A.; Danilov, F.I. Effect of water content on physicochemical properties and electrochemical behavior of ionic liquids containing choline chloride, ethylene glycol and hydrated nickel chloride. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 212, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Birbilis, N.; Wu, G.; Ding, W. Tailoring nickel coatings via electrodeposition from a eutectic-based ionic liquid doped with nicotinic acid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 9094–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

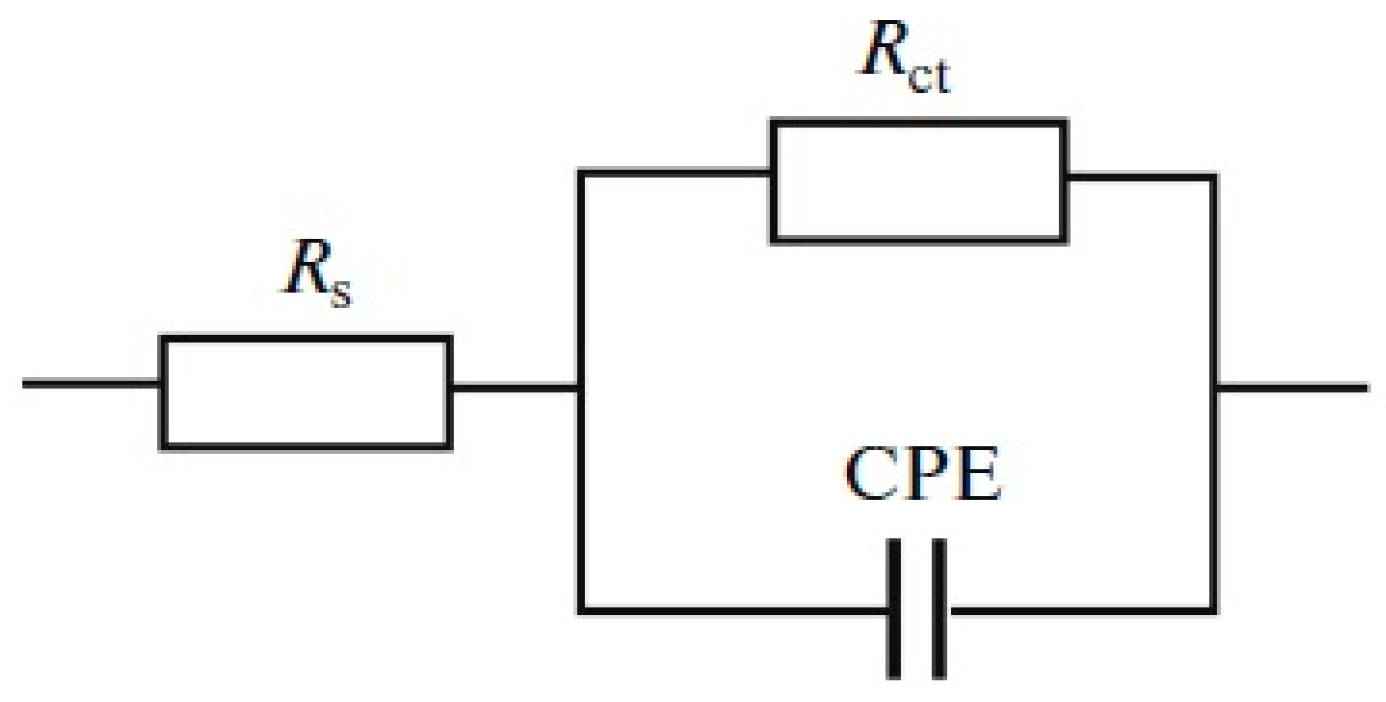

- Mulder, W.H.; Sluyters, J.H. An explanation of depressed semi-circular arcs in impedance plots for irreversible electrode reactions. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 33, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, X.; Yang, H.; Dai, J.C.; Zhu, R.; Gong, J.; Peng, L.; Ding, W. Electrodeposition mechanism and characterization of Ni–Cu alloy coatings from a eutectic-based ionic liquid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 288, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Guo, X.W.; Chen, X.B.; Wang, S.H.; Wu, G.H.; Ding, W.J.; Birbilis, N. On the electrodeposition of nickel–zinc alloys from a eutectic-based ionic liquid. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 63, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.H.; Gu, C.D.; Wang, X.L.; Tu, J.P. Electrodeposition of Ni–Co alloys from a deep eutectic solvent. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 3632–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hao, J.; Mu, S.; Liu, W. Electrochemical behavior and electrodeposition of Ni–Co alloy from choline chloride-ethylene glycol deep eutectic solvent. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 507, 144889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncagliolo Barrera, P.; Echánove Rodríguez, C.; Rodriguez Gomez, F.J. Comparative assessment of Ni–Co coatings obtained from a deep eutectic solvent, choline chloride-ethylene glycol, and water by electroplating. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2023, 27, 3075–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, J.; Mohan, S.; Kumar, S.A.; Suseendiran, S.R.; Pavithra, S. Electrodeposition of Ni–Co–Sn alloy from choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvent and characterization as cathode for hydrogen evolution in alkaline solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 10208–10214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costovici, S.; Manea, A.C.; Visan, T.; Anicai, L. Investigation of Ni-Mo and Co-Mo alloys electrodeposition involving choline chloride based ionic liquids. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 207, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

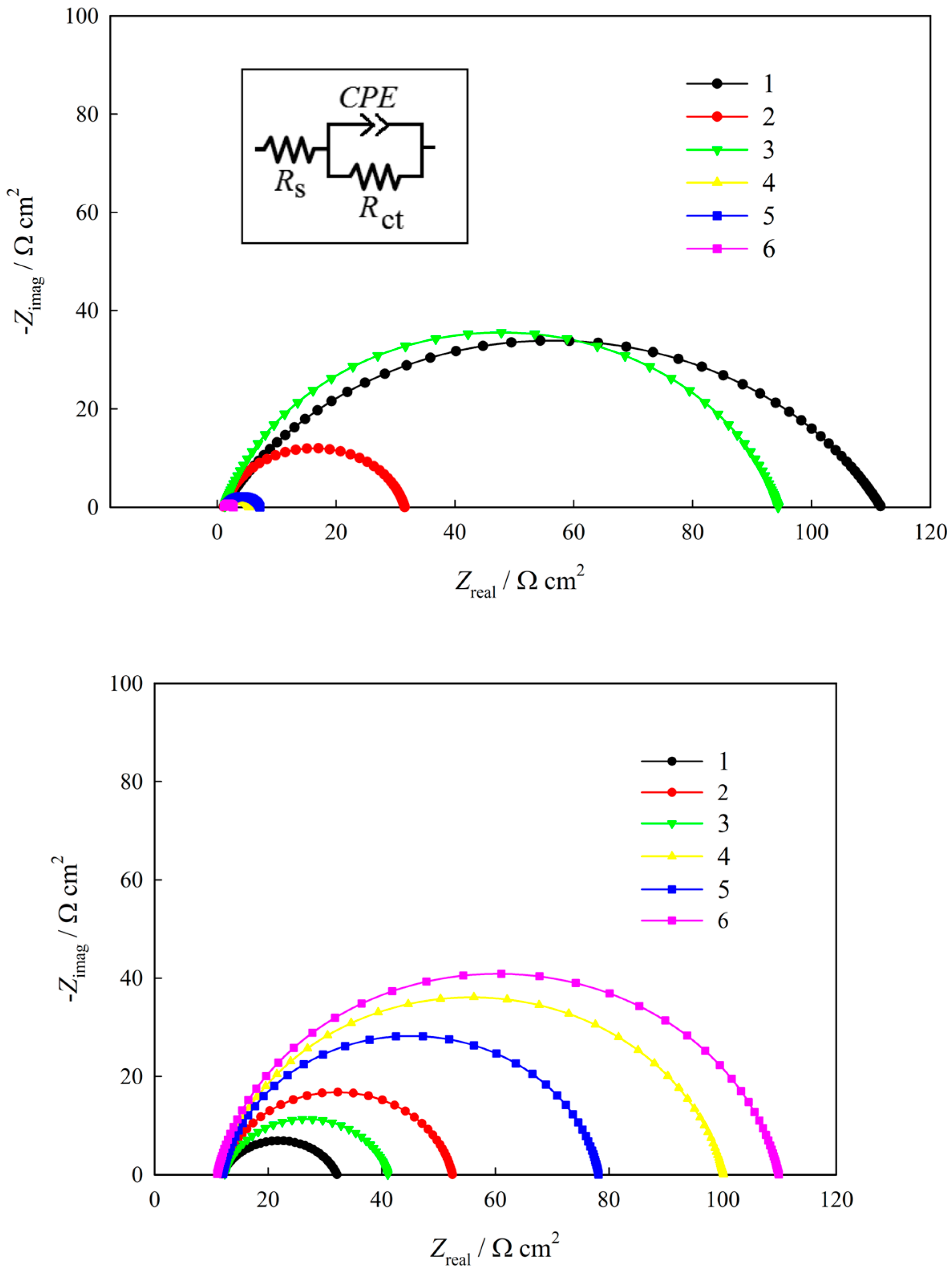

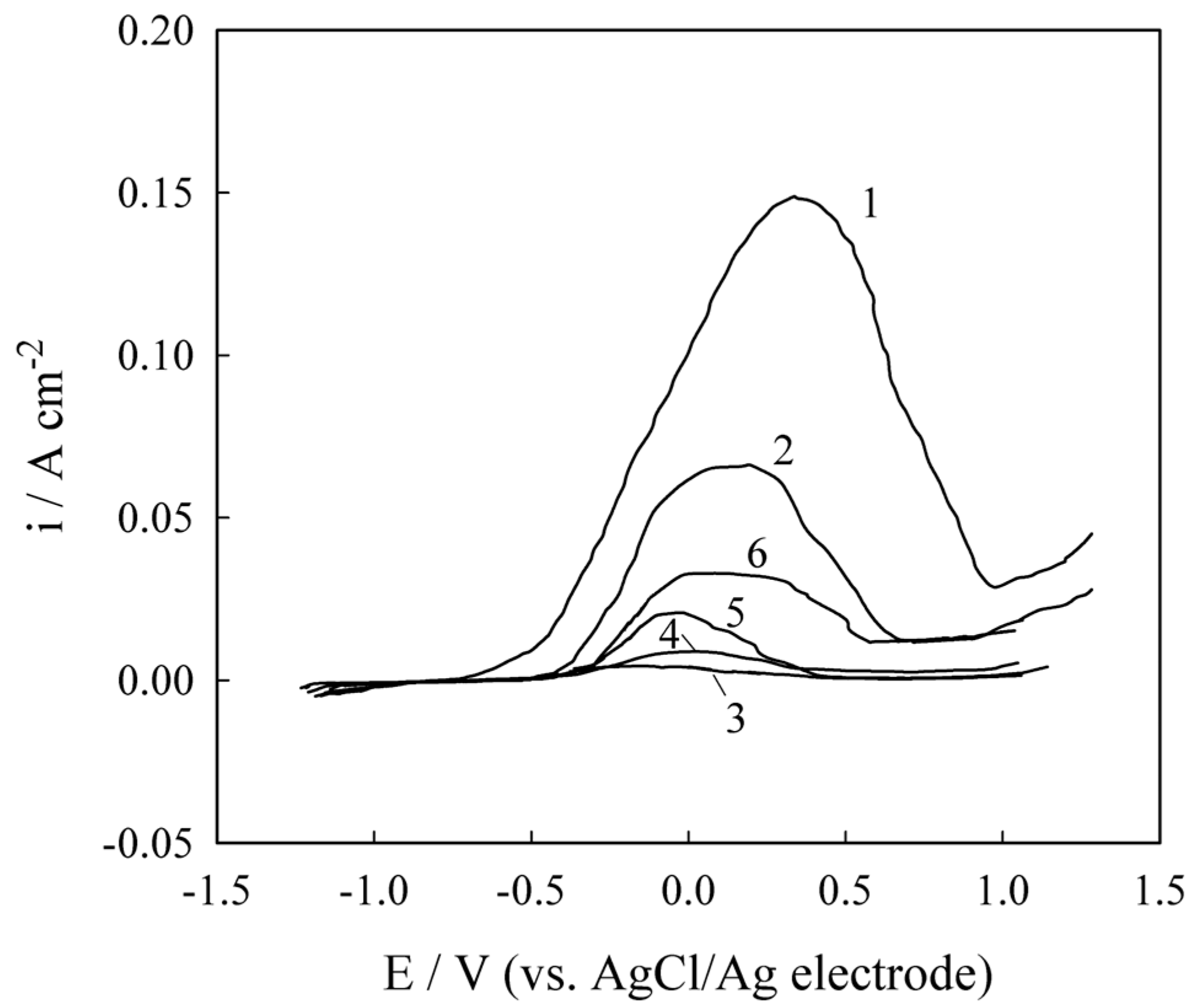

- Protsenko, V.S.; Sukhatskyi, O.D.; Butyrina, T.E.; Frolova, L.A.; Korniy, S.A. Micromodification of nickel-based coatings electrodeposited from a deep eutectic solvent with lanthanum as a way to improve electrocatalytic performance and corrosion resistance. Mater. Lett. 2024, 370, 136892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liang, J.; Fu, S. Ni–Ti nanocomposite coatings electro-codeposited from deep eutectic solvent containing Ti nanoparticles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 042502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, F.I.; Kityk, A.A.; Shaiderov, D.A.; Bogdanov, D.A.; Korniy, S.A.; Protsenko, V.S. Electrodeposition of Ni–TiO2 composite coatings using electrolyte based on a deep eutectic solvent. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 55, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Butyrina, T.E.; Bobrova, L.S.; Korniy, S.A.; Danilov, F.I. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of Ni–TiO2 composite coatings electrodeposited from a deep eutectic solvent-based electrolyte. Coatings 2022, 12, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Nabb, D.; Renevier, N.; Sherrington, I.; Fu, Y.; Luo, J. Mechanical and anti-corrosion properties of TiO2 nanoparticle reinforced Ni coating by electrodeposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, D671–D676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.K.; Such, T.E. Nickel and Chromium Plating, 3rd ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK; 385p.

- Fedrizzi, L.; Rossi, S.; Bellei, F.; Deflorian, F. Wear-corrosion mechanism of hard chromium coatings. Wear 2002, 253, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiopoulou, E.; Gikas, P. Regulations for chromium emissions to the aquatic environment in Europe and elsewhere. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Danilov, F.I. Chromium electroplating from trivalent chromium baths as an environmentally friendly alternative to hazardous hexavalent chromium baths: Comparative study on advantages and disadvantages. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survilienė, S.; Nivinskienė, O.; Češunienė, A.; Selskis, A. Effect of Cr(III) solution chemistry on electrodeposition of chromium. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2006, 36, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.; Danilov, F. Kinetics and mechanism of chromium electrodeposition from formate and oxalate solutions of Cr(III) compounds. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 5666–5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K. Ionic liquid analogues formed from hydrated metal salts. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 3769–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Al-Barzinjy, A.A.; Abbott, P.D.; Frish, G.; Harris, R.C.; Hartley, J.; Ryder, K.S. Speciation, physical and electrolytic properties of eutectic mixtures based on CrCl3·6H2O and urea. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 9047–9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.S.C.; Pereira, C.M.; Silva, A.F. Electrochemical studies of metallic chromium electrodeposition from a Cr(III) bath. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2013, 707, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Caballero, I.; Aldana-González, J.; Manh, T.L.; Romero-Romo, M.; Arce-Estrada, E.M.; Campos-Silva, I.; Ramírez-Silva, M.T.; Palomar-Pardavé, M. Mechanism and kinetics of chromium electrochemical nucleation and growth from a choline chloride/ethylene glycol deep eutectic solvent. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, D393–D401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.; Bobrova, L.; Danilov, F. Trivalent chromium electrodeposition using a deep eutectic solvent. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2018, 65, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Bobrova, L.S.; Baskevich, A.S.; Korniy, S.A.; Danilov, F.I. Electrodeposition of chromium coatings from a choline chloride based ionic liquid with the addition of water. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2018, 53, 906–915. [Google Scholar]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Bobrova, L.S.; Korniy, S.A.; Kityk, A.A.; Danilov, F.I. Corrosion resistance and protective properties of chromium coatings electrodeposited from an electrolyte based on deep eutectic solvent. Funct. Mater. 2018, 25, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Bobrova, L.S.; Kityk, A.A.; Danilov, F.I. Kinetics of Cr(III) ions discharge in solutions based on a deep eutectic solvent (ethaline): Effect of water addition. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 864, 114086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Bobrova, L.S.; Korniy, S.A.; Danilov, F.I. Electrochemical synthesis and characterization of electrocatalytic materials for hydrogen production using Cr(III) baths based on a deep eutectic solvent. Mater. Lett. 2022, 313, 131800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, V.S.; Gordiienko, V.O.; Danilov, F.I. Unusual “chemical” mechanism of carbon co-deposition in Cr-C alloy electrodeposition process from trivalent chromium bath. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 17, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, F.I.; Protsenko, V.S.; Gordiienko, V.O.; Kwon, S.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, M. Nanocrystalline hard chromium electrodeposition from trivalent chromium bath containing carbamide and formic acid: Structure, composition, electrochemical corrosion behavior, hardness and wear characteristics of deposits. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 8048–8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gu, C.; Tong, Y.; Gou, J.; Wang, X.; Tu, J. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of Cr and Cr–P alloy coatings electrodeposited from a Cr(III) deep eutectic solvent. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 71268–71277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Ru, J.; Hua, Y.; Bu, J.; Wang, D. Eco-friendly preparation of nanocrystalline Fe-Cr alloy coating by electrodeposition in deep eutectic solvent without any additives for anti-corrosion. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 406, 126636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Geng, X.; Ru, J.; Hua, Y.; Bu, J.; Xue, Y.; Wang, D. The role of electrolyte ratio in electrodeposition of nanoscale Fe–Cr alloy from choline chloride-ethylene glycol ionic liquid: A suitable layer for corrosion resistance. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 117059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, G.; Mohan, S. Electrodeposition of Fe-Ni-Cr alloy from deep eutectic system containing choline chloride and ethylene glycol. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, V.; Höhlich, D.; Mehner, T.; Lampke, T. Electrodeposition of thick and crack-free Fe-Cr-Ni coatings from a Cr (III) electrolyte. Coatings 2022, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaja, J.; Raja, M.; Mohan, S. Pulse electrodeposition of Cr–SWCNT composite from choline chloride-based electrolyte. Surf. Eng. 2014, 30, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substance or Eutectic Mixture | Melting Point, °C |

|---|---|

| ethylene glycol | −12.9 |

| urea | 134 |

| choline chloride | 303 |

| DES ethaline (ethylene glycol + choline chloride) | −66 |

| DES reline (urea + choline chloride) | 12 |

| Sample | Ecorr (mV vs. Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode) | jcorr (μA cm−2) |

|---|---|---|

| Fe substrate | −402 | 7.5 |

| 20% Ni deposited from ChCl/EG 1:2 | −902 | 1.6 |

| 20% Ni deposited from ChCl/EG 1:4.5 | −859 | 4.3 |

| 15% Ni deposited from ChCl/EG 1:4.5 | −774 | 3.7 |

| 12% Ni deposited from ChCl/EG 1:4.5 | −853 | 7.9 |

| 18% Ni deposited from pure EG | −852 | 18.1 |

| 15% Ni deposited from commercial ZnNi plating bath | −826 | 11.8 |

| System 1 | Rs, Ω | Rct, Ω | Q, Ω−1 sn | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethaline + NiCl2·6H2O | 11.37 | 8.45 | 78.81 × 10−3 | 0.526 |

| Ethaline + NiCl2·9H2O | 11.22 | 8.81 | 68.24 × 10−3 | 0.530 |

| Ethaline + NiCl2·12H2O | 11.49 | 8.85 | 51.04 × 10−3 | 0.629 |

| Ethaline + NiCl2·15H2O | 11.05 | 16.32 | 1.24 × 10−3 | 0.985 |

| Ethaline + NiCl2·18H2O | 10.61 | 22.83 | 84.61 × 10−6 | 0.991 |

| Sample Number | Content of La in Coating/wt.% | Parameters for Hydrogen Evolution | Parameters for Corrosion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rs/Ω | Rct/Ω cm2 | CPE | Rs/Ω | Rct/Ω cm2 | CPE | ||||

| Y/Ω−1 sn cm−2 | n | Y/Ω−1 sn cm−2 | n | ||||||

| 1 | – | 1.05 | 110.65 | 6.80 × 10−4 | 0.70 | 11.85 | 20.28 | 17.80 × 10−5 | 0.76 |

| 2 | 0.65 | 1.15 | 30.40 | 8.80 × 10−5 | 0.85 | 11.90 | 40.55 | 7.80 × 10−5 | 0.88 |

| 3 | 0.48 | 1.20 | 93.18 | 7.48 × 10−5 | 0.83 | 12.35 | 28.73 | 8.95 × 10−5 | 0.85 |

| 4 | 1.51 | 1.80 | 3.60 | 6.95 × 10−5 | 0.79 | 11.45 | 88.70 | 6.12 × 10−5 | 0.87 |

| 5 | 1.41 | 1.35 | 5.84 | 7.82 × 10−5 | 0.81 | 12.05 | 66.12 | 6.44 × 10−5 | 0.90 |

| 6 | 1.75 | 1.15 | 1.55 | 5.67 × 10−5 | 0.87 | 11.00 | 98.87 | 6.06 × 10−5 | 0.88 |

| Coating | Ecorr (mV) | jcorr (mA cm−2) |

|---|---|---|

| Ni | −508 | 9.31 × 10−6 |

| Ni–TiO2 (5%) | −451 | 3.45 × 10−6 |

| Ni–TiO2 (10%) | −408 | 1.28 × 10−6 |

| Chromium Deposits Thickness (μm) | DP (%) |

|---|---|

| 2.5 | 55.8 |

| 5 | 97.5 |

| 10 | 94.1 |

| 15 | 86.4 |

| 20 | 78.3 |

| Thickness of Deposit (μm) | Rs (Ω) | Characteristics of Corrosion of Cr Deposits | Characteristics of Corrosion of Steel Substrate Through Pores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rc (Ω cm2) | Qc × 106 (Ω−1 sn cm−2) | nc | Rp (Ω cm2) | Qp × 103 (Ω−1 sn cm−2) | np | ||

| – (steel substrate) | 10.5 | – | – | – | 748 | 2010 | 0.650 |

| 2.5 | 10.5 | 940 | 1180 | 0.675 | 2199 | 4.09 | 0.700 |

| 5 | 10.0 | 5050 | 39 | 0.959 | 3595 | 0.73 | 0.998 |

| 10 | 10.3 | 2310 | 200 | 0.807 | 3100 | 2.5 | 0.997 |

| 15 | 10.4 | 1010 | 680 | 0.795 | 2500 | 2.9 | 0.800 |

| 20 | 10.2 | 950 | 780 | 0.755 | 2200 | 3.9 | 0.500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Protsenko, V.S. Electrochemical Corrosion Properties and Protective Performance of Coatings Electrodeposited from Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Electrolytes: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030558

Protsenko VS. Electrochemical Corrosion Properties and Protective Performance of Coatings Electrodeposited from Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Electrolytes: A Review. Materials. 2025; 18(3):558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030558

Chicago/Turabian StyleProtsenko, Vyacheslav S. 2025. "Electrochemical Corrosion Properties and Protective Performance of Coatings Electrodeposited from Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Electrolytes: A Review" Materials 18, no. 3: 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030558

APA StyleProtsenko, V. S. (2025). Electrochemical Corrosion Properties and Protective Performance of Coatings Electrodeposited from Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Electrolytes: A Review. Materials, 18(3), 558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18030558