Thermal Barrier Coating on Diamond Particles for the SPS Sintering of the Diamond–ZrO2 Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

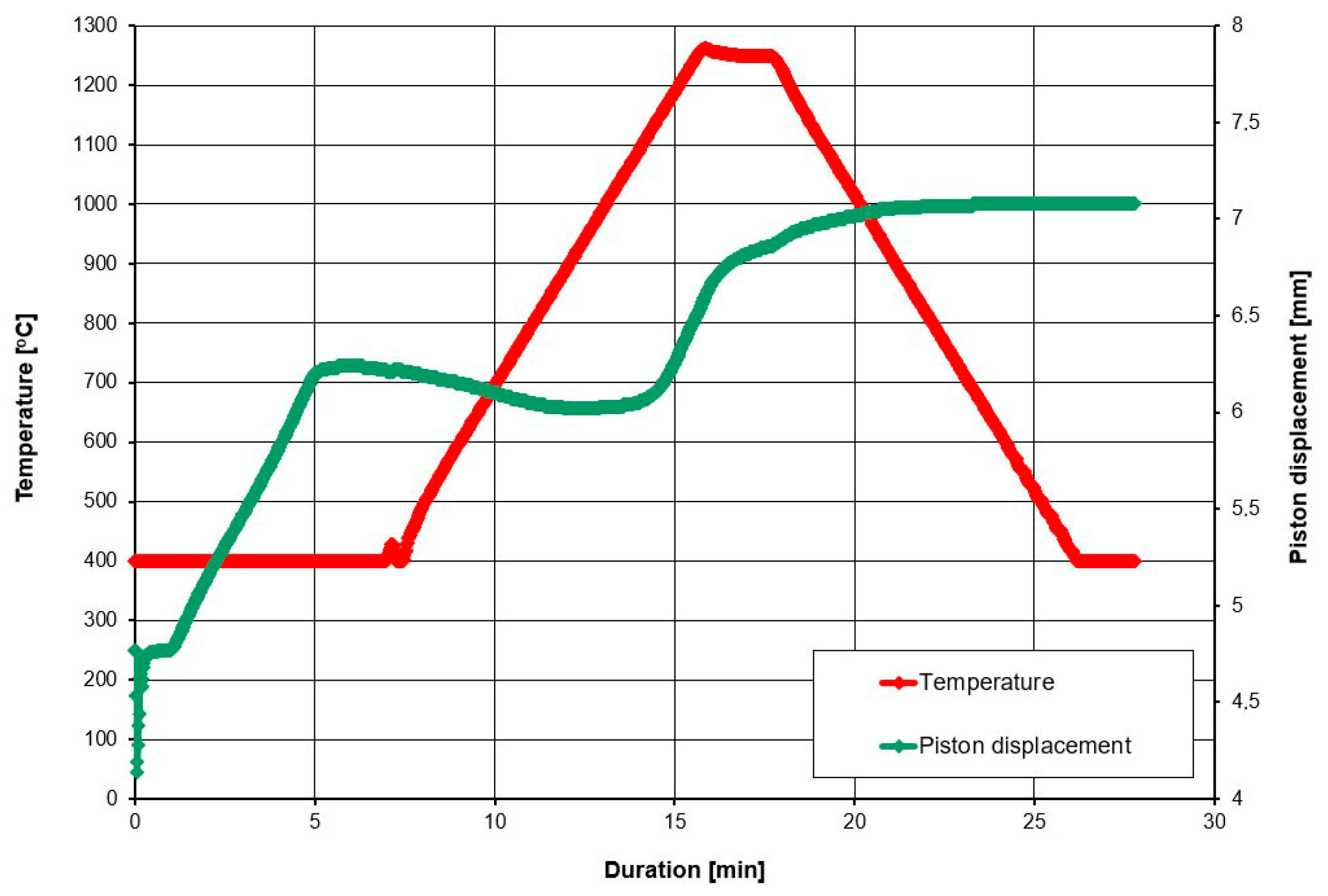

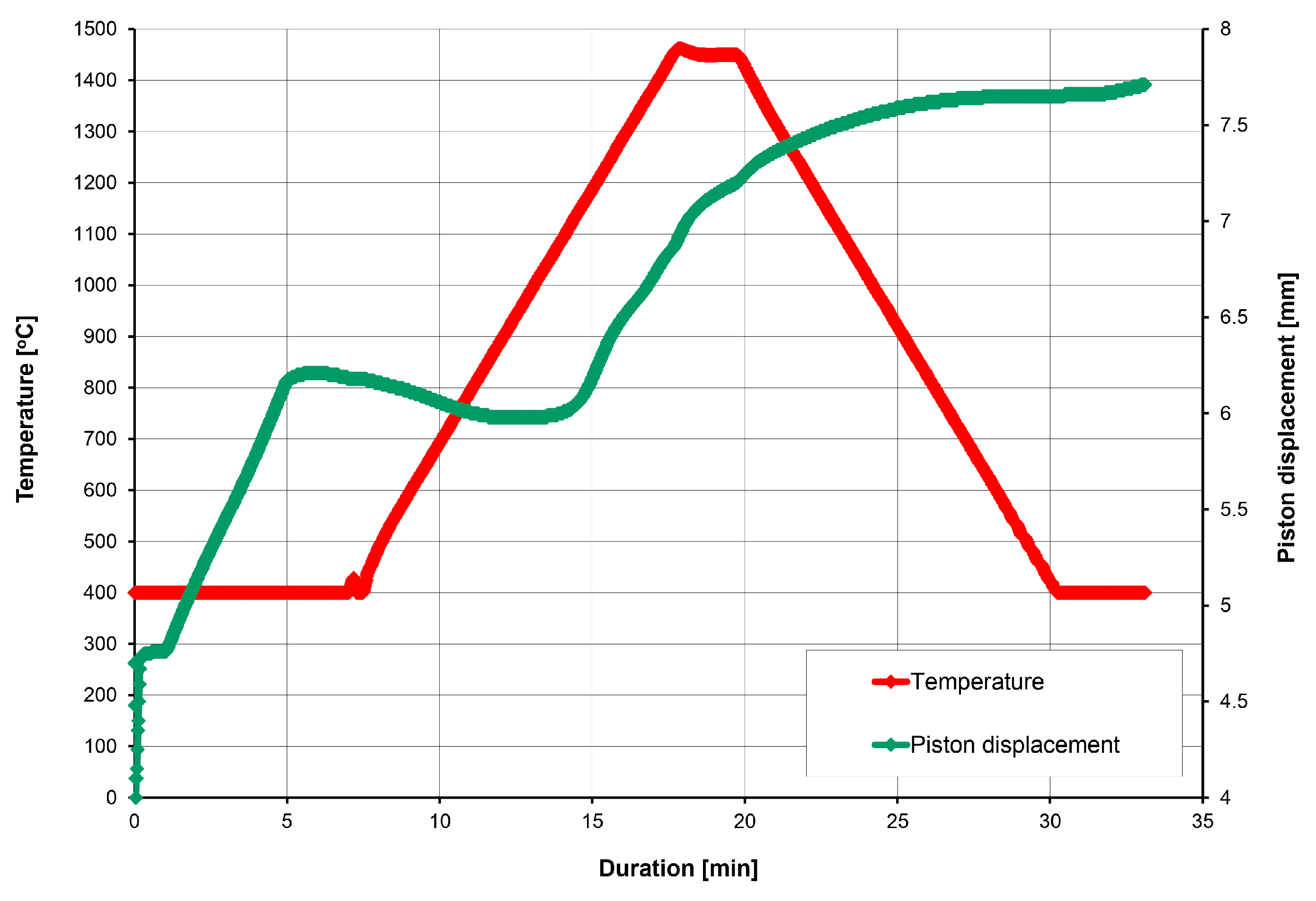

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

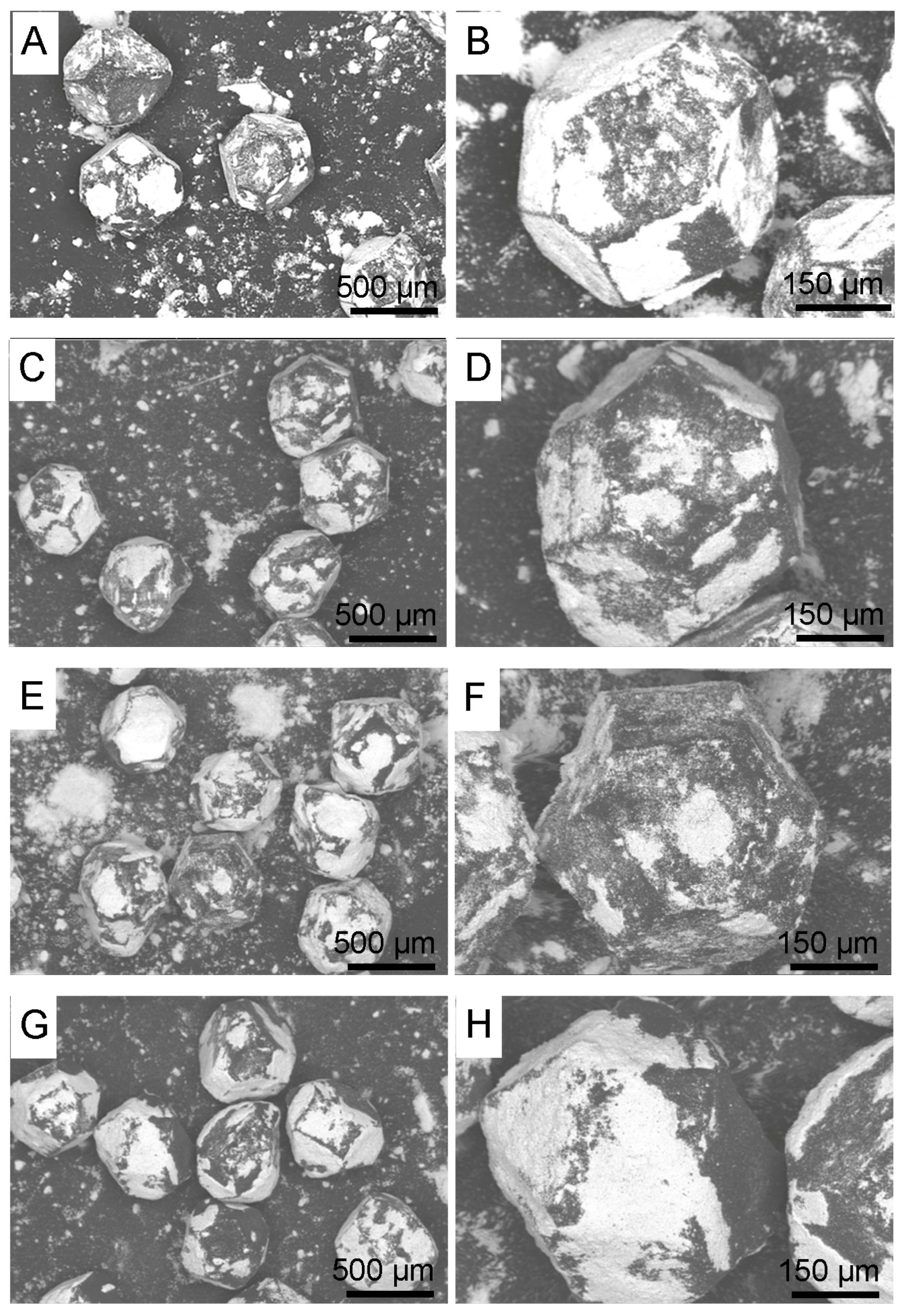

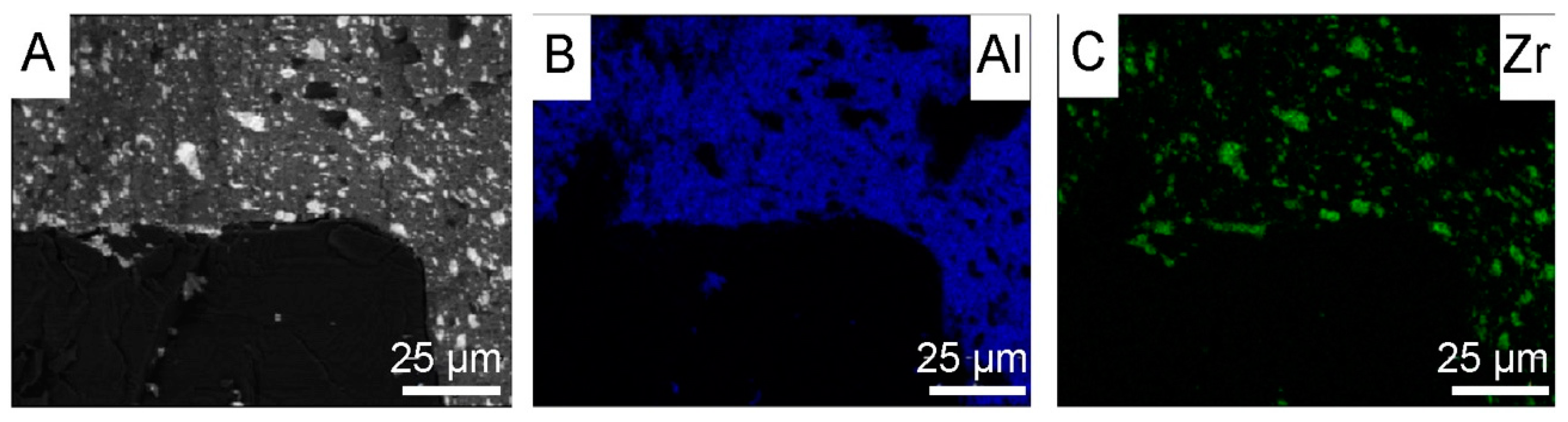

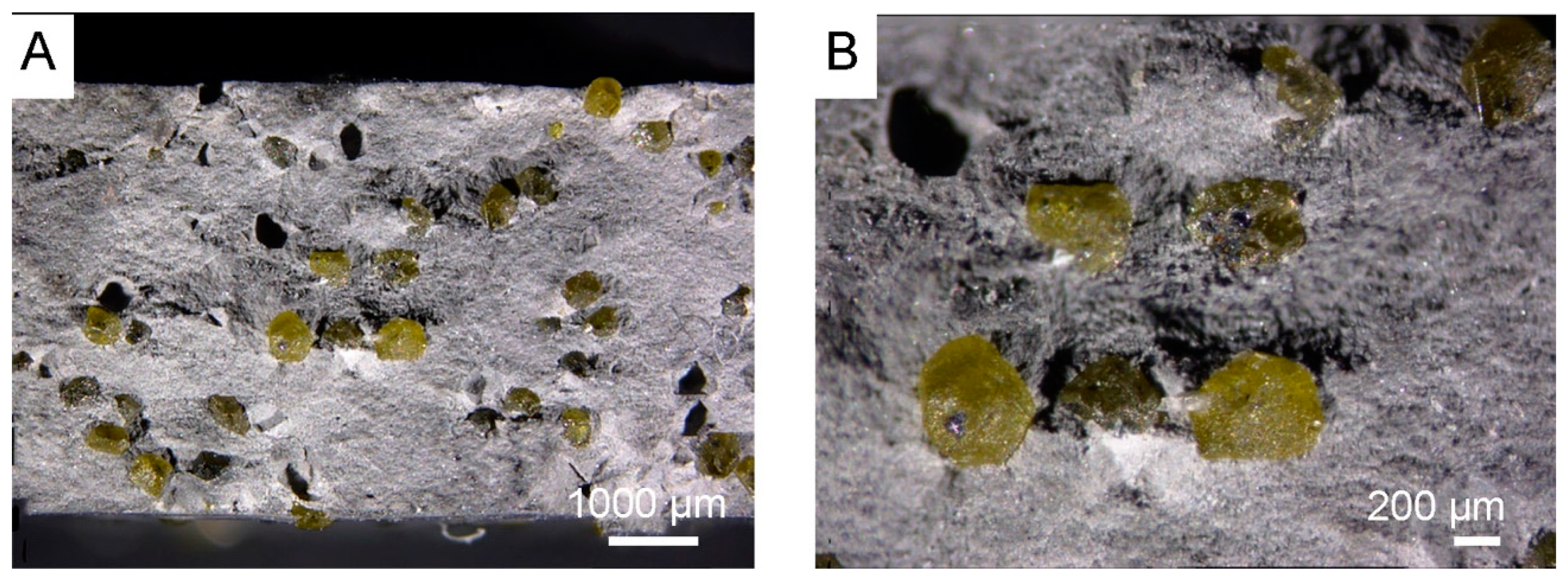

3.1. Morphology of Diamond Powders

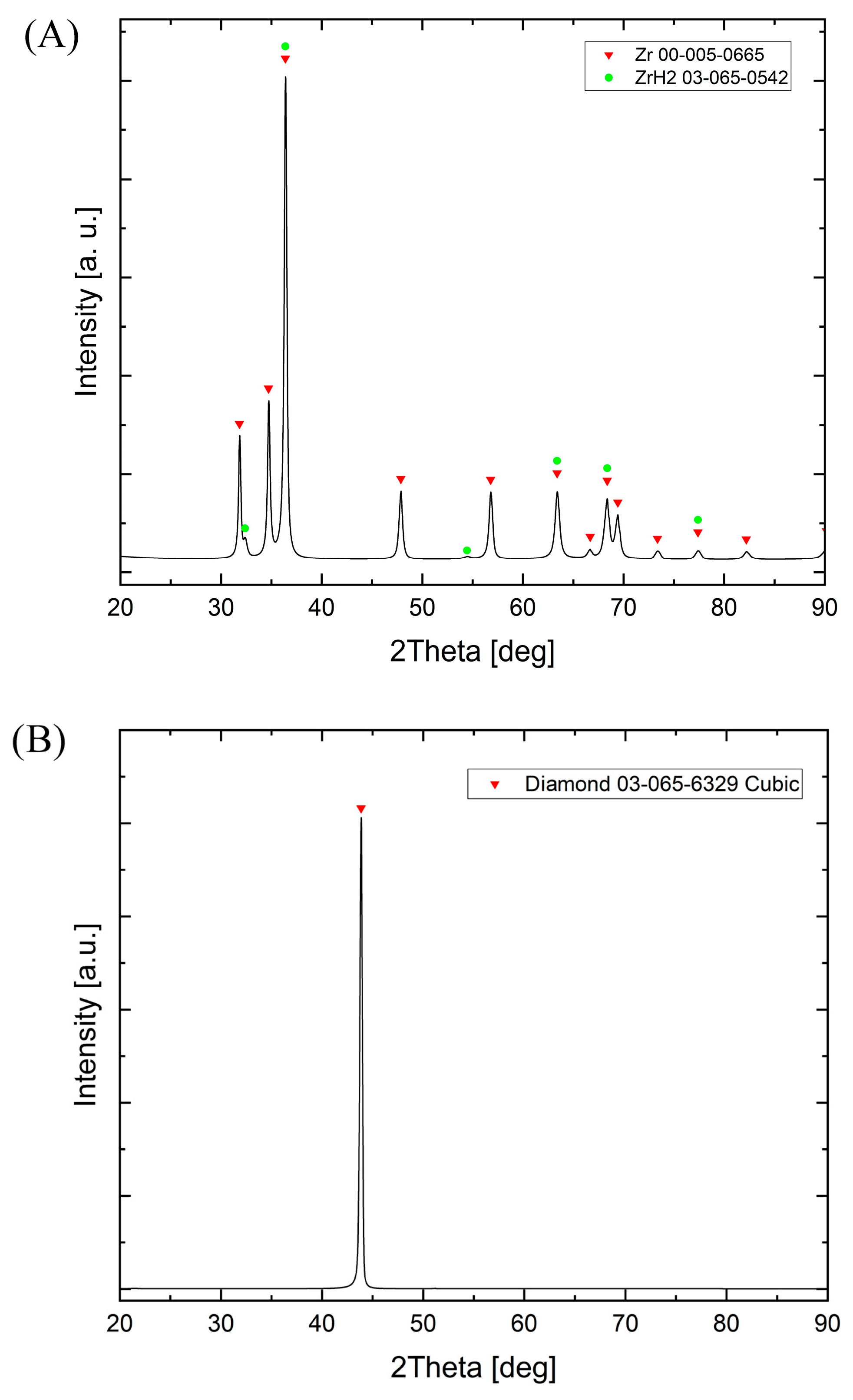

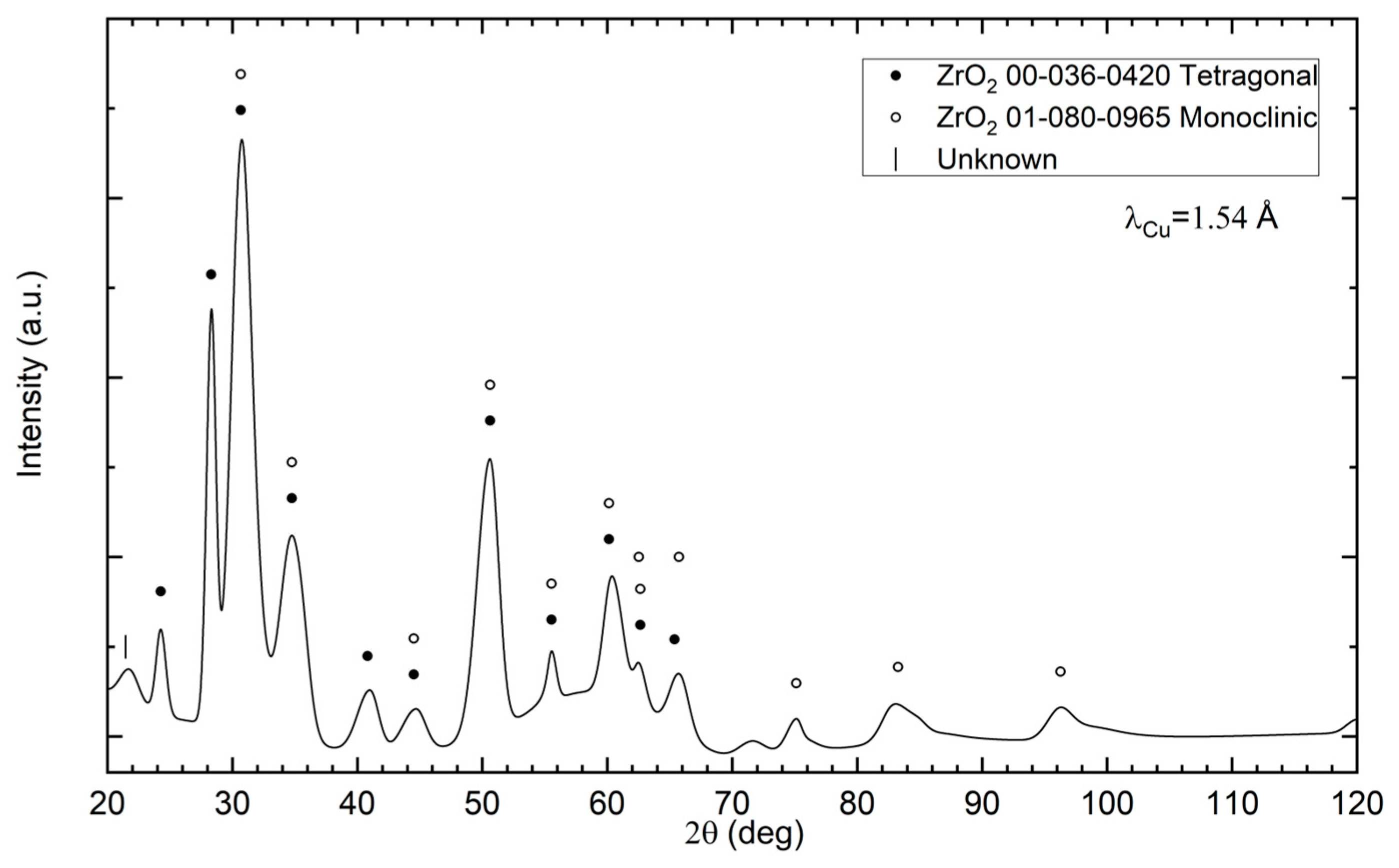

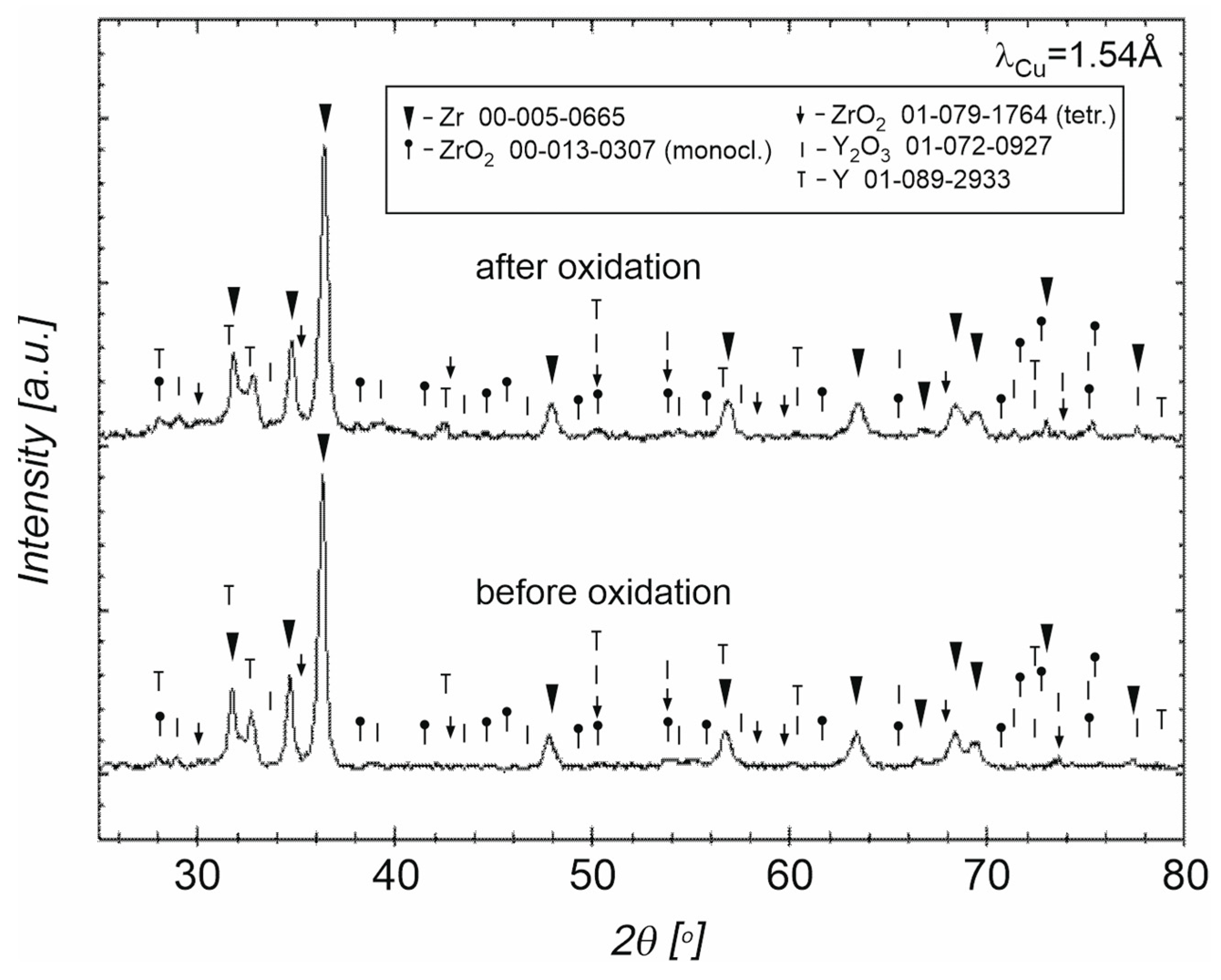

3.2. Phase Compositions of Diamond Powders

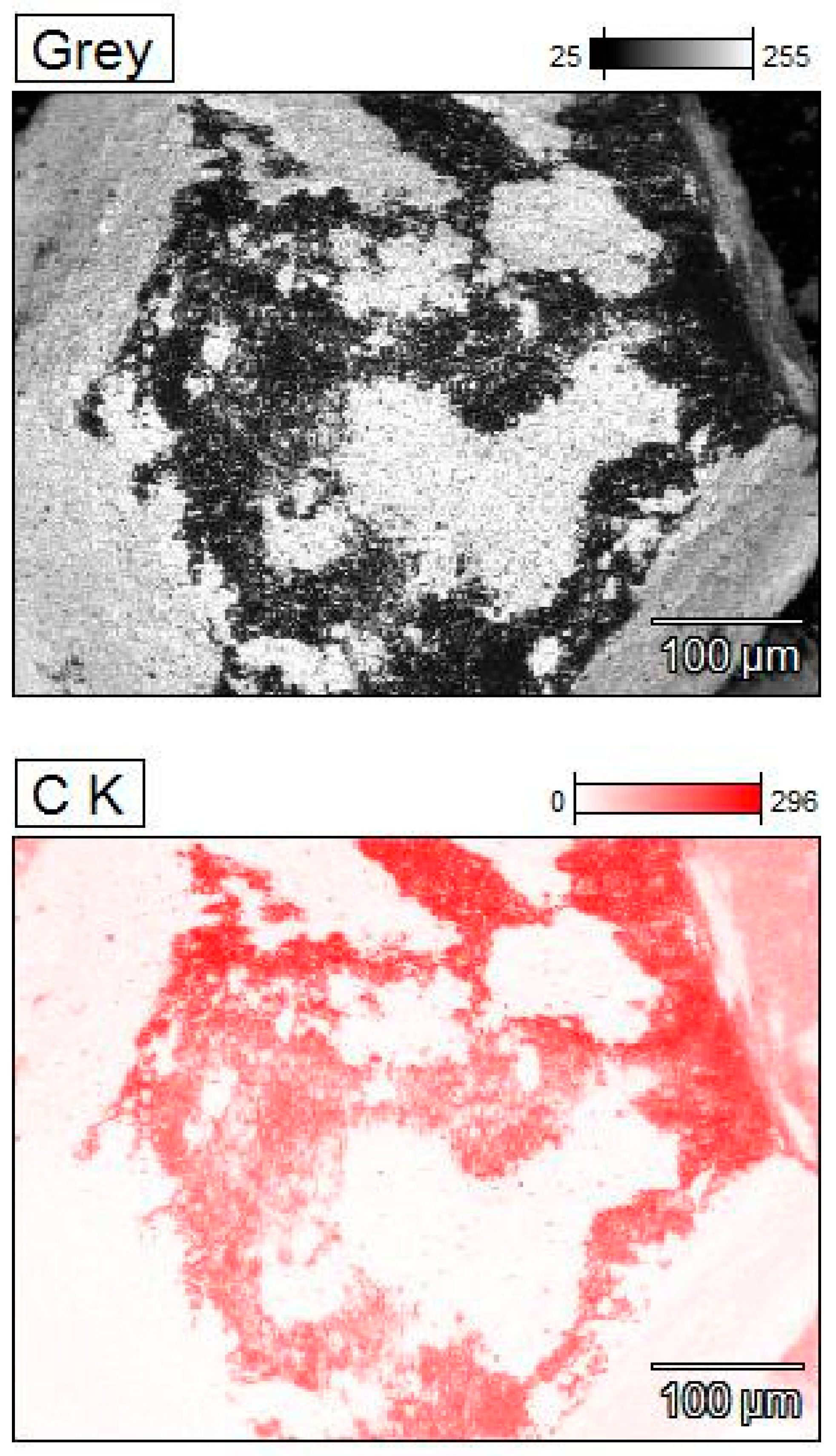

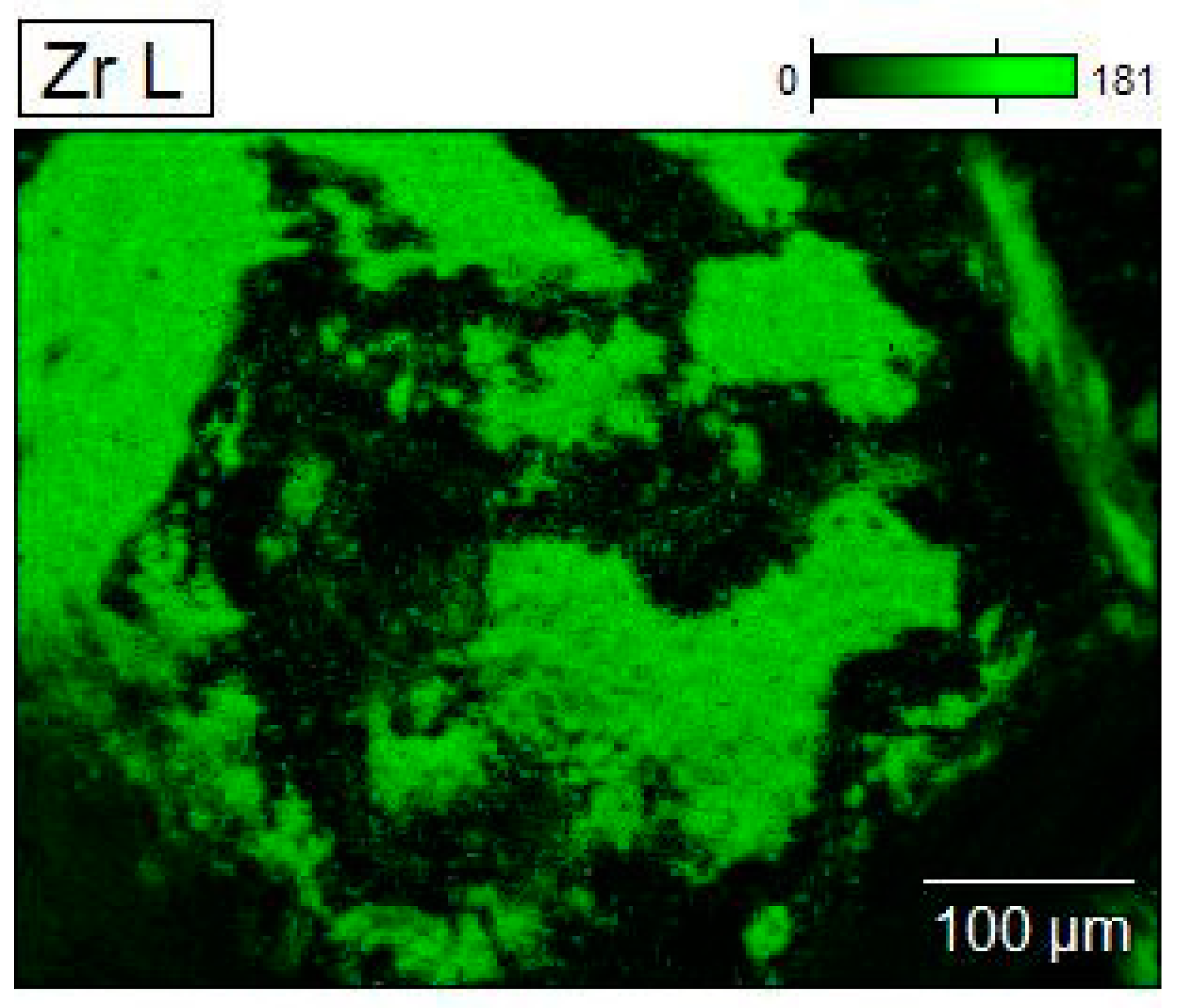

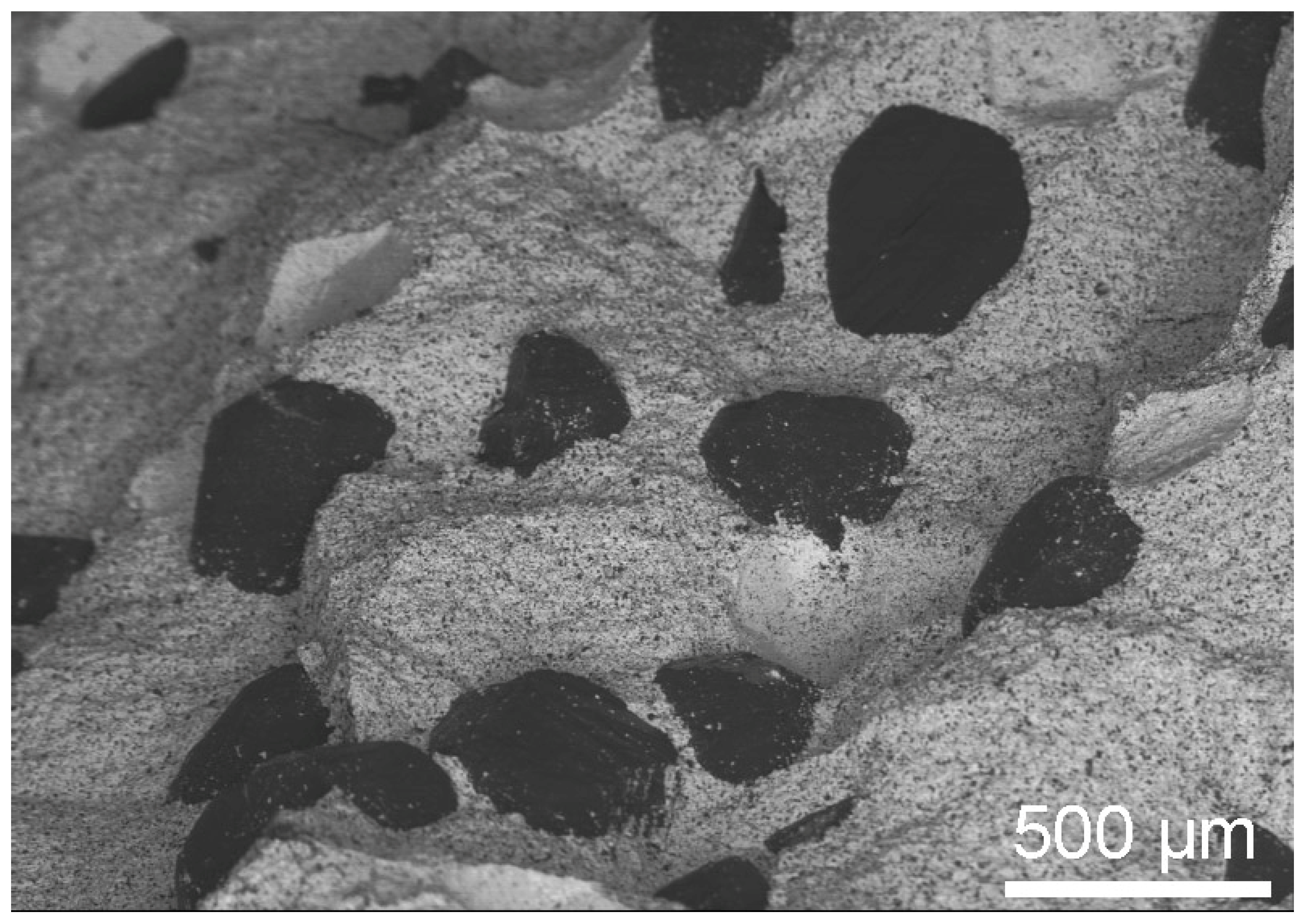

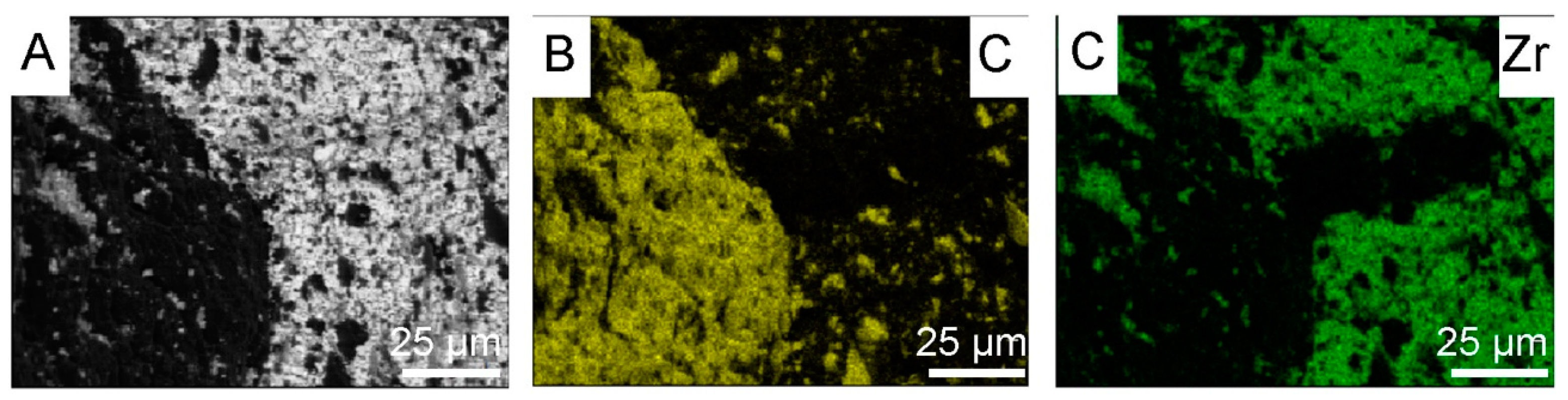

3.3. Powders After SPS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Enckevort, W.J.P.; De Theije, F.K. Etching of diamond. In Properties, Growth and Application of Diamond; Nazare, M.H., Neves, A.J., Eds.; Institution of Electrical Engineers INSPEC: London, UK, 2001; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T.; Sauter, D.H. Etching of diamond surfaces with gases. Philos. Mag.-J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 1961, 6, 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T. Changes produced by high temperature treatment of diamond. In The Properties of Diamond, 1st ed.; Field, J.E., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1979; pp. 403–423. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Rahim, M.Z.; Pan, W.; Wen, C.; Ding, S. The manufacturing and the application of polycrystalline diamond tools—A comprehensive review. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 56 Pt A, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.M. Sintering window and sintering mechanism for diamond. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 117, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, Y.; Liang, W.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, L.; He, D. Effect of stress state on graphitization behavior of diamond under high pressure and high temperature. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 128, 109241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Bellezze, T.; Cabibbo, M.; Gamsjäger, E.; Wiessner, M.; Rajnovic, D.; Jaworska, L.; Hanus, P.; Shishkin, A.; Goel, G.; et al. Solutions of Critical Raw Materials Issues Regarding Iron-Based Alloys. Materials 2021, 14, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstanty, J. Cobalt as a Matrix in Diamond Impregnated Tools for Stone Sawing Applications; AGH Uczelniane Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Dydaktyczne: Kraków, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworska, L.; Szutkowska, M.; Klimczyk, P.; Sitarz, M.; Bucko, M.; Rutkowski, P.; Figiel, P.; Lojewska, J. Oxidation, graphitization and thermal resistance of PCD materials with the various bonding phases of up to 800 °C. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2014, 45, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelnitsky, R.A.; Gippius, A.A. Transformation of diamond to graphite under heat treatment at low pressure. Phase Transit. 2013, 87, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yan, G.; Yue, W.; Lin, F.; Wang, C. Thermal damage mechanisms of Si-coated diamond powder based polycrystalline diamond. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 4338–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Yue, W.; Zhang, H.; Qin, W.; She, D.; Wang, C. Enhanced oxidation and graphitization resistance of polycrystalline diamond sintered with Ti-coated diamond powders. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zang, J.B.; Wang, M.Z.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, Y.Z. Properties and applications of Ti-coated diamond grits. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 129, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Effect of diffusion barrier and interfacial strengthening on the interface behavior between high entropy alloy and diamond. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 852, 157023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Catalano, M.; Bai, G.; Li, N.; Dai, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Kim, M.J. Enhanced thermal conductivity in Cu/diamond composites by tailoring the thickness of interfacial TiC layer. Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 113, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Zang, J.; Shen, W.; Huang, G.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Wan, B.; Jia, X.; et al. High hardness and high fracture toughness B4C-diamond ceramics obtained by high-pressure sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 3090–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Yue, W.; Zhang, H.; Qin, W.; She, D.; Wang, C. Thermal stability of polycrystalline diamond compact sintered with boron-coated diamond particles. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 104, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Choi, H.-L.; Ahn, Y.-S. Chromium carbide coating of diamond particles using low temperature molten salt mixture. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 805, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Adloff, L.; Matthey, B.; Gestrich, T. Oxidation behaviour of silicon carbide bonded diamond materials. Open Ceram. 2020, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Fukuoka, K.; Arata, Y.; Yonezawa, S.; Kiyokawa, H.; Takashima, M. Tungsten carbide coating on diamond particles in molten mixture of Na2CO3 and NaCl. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2015, 52, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Shao, G.; Duan, X.; Xiong, Z.; Yang, H. The Effect of Tungsten Buffer Layer on the Stability of Diamond with Tungsten Carbide–Cobalt Nanocomposite Powder During Spark Plasma Sintering. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2006, 15, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Hu, C.; Maizza, G.; Sakkak, Y. Spark Plasma Sintering of Diamond Binderless WC Composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 95, 2423–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, H.; Tsuduki, K.; Ikegaya, A.; Miyamoto, Y.; Morisada, Y. Sintering Behavior and Properties of Diamond/Cemented Carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2007, 25, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczyk, P.; Cura, M.E.; Vlaicu, A.M.; Mercioniu, I.; Wyżga, P.; Jaworska, L.; Hannula, S.-P. Al2O3–cBN composites sintered by SPS and HPHT methods. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczyk, P.; Wyżga, P.; Cyboroń, J.; Laszkiewicz-Łukasik, J.; Podsiadło, M.; Cygan, S.; Jaworska, L. Phase stability and mechanical properties of Al2O3-cBN composites prepared via spark plasma sintering. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2020, 104, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pędzich, Z. Fracture of oxide matrix composites with different phase arrangement. Key Eng. Mater. 2009, 409, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L. Thermal barrier coatings. In Metallurgical and Ceramic Protective Coatings; Stern, K.H., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1996; pp. 194–235. [Google Scholar]

- Garvie, R.C.; Hannink, R.H.; Pascoe, R.T. Ceramic steel. Nature 1975, 258, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richerson, D.W. Modern Ceramic Engineering: Properties, Processing, and Use in Design; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 38–45, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Nettleship, I.; Stevens, R. Tetragonal zirconia polycrystal (TZP)—A review. Int. J. High Technol. Ceram. 1987, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunin, V.F.; Korovin, S.A. Preparation of Nanocrystalline Powders of ZrO2, Stabilized by Y2O3 Dobs for Ceramics. Phys. Procedia 2015, 72, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Bayer, T.J.M.; Guo, J.; Baker, A.; Randall, C.A. Cold sintering process for 8 mol%Y2O3-stabilized ZrO2 ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 37, 2303–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecura, S. Optimization of the NiCrAl-Y/ZrO-Y2O3 thermal barrier system. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the American Ceramic Society Conference: American Ceramic Society Annual Meeting, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 5–9 May 1985. CONF-850536-2. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.R.; Phillpot, S.R. Thermal barrier coating materials. Mater. Today Commun. 2005, 8, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.C.; Xu, W.J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zeng, H.P. In-flight behaviors of ZrO2 particle in plasma spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 5671–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumm, D.R.; Evans, A.G.; Spitsberg, I.T. Characterization of a cyclic displacement instability for a thermally grown oxide in a thermal barrier system. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, A.; Rosiński, M. Sintering Diamond/Cemented Carbides by the Pulse Plasma Sintering Method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 3560–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Katsui, H.; Goto, T. High-Hardness Diamond Composite Consolidated by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99, 1862–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, F.P. Phase diagram of carbon. Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. 1995, 383, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, L.; Wnuk, R.; Nowak, P.; Stępień, M.; Boczkal, G.; Noga, P.; Skrzekut, T. Sintering of alloyed zirconium powders and selected properties at high temperatures. In Proceedings of the WORLD PM2024 Powder Metallurgy World Congress & Exhibition, Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, V.; Seifert, H.J.; Aldinger, F. Thermodynamic properties of Y2O3 phases and the yttrium–oxygen phase diagram. J. Alloys Compd. 1998, 269, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchala, B.; Van Der Ven, A. Thermodynamics of the Zr-O system from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 094108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsanzadeh-Vadeqani, M.; Shoja Razavi, R. Spark plasma sintering of zirconia-doped yttria ceramic and evaluation of the microstructure and optical properties. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18931–18936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.S.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, J.; Hao, Y.; Yu, B.R.; Li, Y.H. The structural phase transition and elastic properties of zirconia under high pressure from first-principles calculations. Solid State Sci. 2011, 13, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.; Gremillard, L.; Virkar, A.V.; Clarke, D.R. The Tetragonal-Monoclinic Transformation in Zirconia: Lessons Learned and Future Trends. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1901–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffner, J.; Latteman, M.; Hahn, H.; Giebeler, L.; Hess, C.; Garcia Cano, I.; Dosta, S.; Guilemany, J.P.; Musa, C.; Locci, A.M.; et al. Microstructure Evolution During Spark Plasma Sintering of Metastable (ZrO2–3 mol% Y2O3)–20 wt% Al2O3 Composite Powders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 93, 2864–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zirconium (Zr) Powder—CA-% Metal Basic | |

|---|---|

| Cl | <0.02 |

| Fe | <0.2 |

| Ca | <0.02 |

| Sn | <0.3 |

| Hf | <0.5 |

| Al | <0.05 |

| Mg | <0.1 |

| Si | <0.08 |

| H—75 µm and 45 µm size | <0.1 |

| H—2 µm size | =0.5–1 wt%—protected |

| Zr | 99% |

| Materials | Composition [wt%] | Mixing Duration [h] | Temperature of Sintering [°C] | Pressure of Sintering [MPa] | Duration of Sintering [min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond 500–350 μm + Zr | 20 80 | 120 | 1250 | 60 | 2 |

| Diamond 500–350 μm + Zr | 20 80 | 120 | 1450 | 60 | 2 |

| Diamond 300–250 μm + Zr | 80 20 | 30 | 1250 | 60 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaworska, L.; Stępień, M.; Witkowska, M.; Skrzekut, T.; Noga, P.; Podsiadło, M.; Tyrała, D.; Konstanty, J.; Kapica, K. Thermal Barrier Coating on Diamond Particles for the SPS Sintering of the Diamond–ZrO2 Composite. Materials 2025, 18, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18040869

Jaworska L, Stępień M, Witkowska M, Skrzekut T, Noga P, Podsiadło M, Tyrała D, Konstanty J, Kapica K. Thermal Barrier Coating on Diamond Particles for the SPS Sintering of the Diamond–ZrO2 Composite. Materials. 2025; 18(4):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18040869

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaworska, Lucyna, Michał Stępień, Małgorzata Witkowska, Tomasz Skrzekut, Piotr Noga, Marcin Podsiadło, Dorota Tyrała, Janusz Konstanty, and Karolina Kapica. 2025. "Thermal Barrier Coating on Diamond Particles for the SPS Sintering of the Diamond–ZrO2 Composite" Materials 18, no. 4: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18040869

APA StyleJaworska, L., Stępień, M., Witkowska, M., Skrzekut, T., Noga, P., Podsiadło, M., Tyrała, D., Konstanty, J., & Kapica, K. (2025). Thermal Barrier Coating on Diamond Particles for the SPS Sintering of the Diamond–ZrO2 Composite. Materials, 18(4), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18040869