Abstract

In this paper, we study the relationship of parameterized enumeration complexity classes defined by Creignou et al. (MFCS 2013). Specifically, we introduce two hierarchies (IncFPTa and CapIncFPTa) of enumeration complexity classes for incremental fpt-time in terms of exponent slices and show how they interleave. Furthermore, we define several parameterized function classes and, in particular, introduce the parameterized counterpart of the class of nondeterministic multivalued functions with values that are polynomially verifiable and guaranteed to exist, TFNP, known from Megiddo and Papadimitriou (TCS 1991). We show that this class TF(para-NP), the restriction of the function variant of NP to total functions, collapsing to F(FPT), the function variant of FPT, is equivalent to the result that OutputFPT coincides with IncFPT. In addition, these collapses are shown to be equivalent to TFNP = FP, and also equivalent to P equals NP intersected with coNP. Finally, we show that these two collapses are equivalent to the collapse of IncP and OutputP in the classical setting. These results are the first direct connections of collapses in parameterized enumeration complexity to collapses in classical enumeration complexity, parameterized function complexity, classical function complexity, and computational complexity theory.

1. Introduction

1.1. Enumeration

In 1988, Johnson, Papadimitriou, and Yannakakis [1] laid the cornerstone of enumeration algorithms. In modern times of ubiquitous computing, such algorithms are of central importance in several areas of life and research such as combinatorics, computational geometry, and operations research [2]. Beyond that, recent results unveil major importance in web search, data mining, bioinformatics, and computational linguistics [3]. Moreover, there are connections to formal languages on enumeration problems for probabilistic automata [4].

Clearly, for enumeration algorithms, one is not primarily interested in their runtime complexity, whereas the time elapsed between two consecutive outputs of such an algorithm is of utmost interest. As a result, one measures the delay of such algorithms. The main goal is to achieve a uniform stream of printed solutions. In this context, the complexity class , that is, polynomial delay, is regarded as an efficient way of enumeration. Enumeration algorithms for problems in that particular class print every -many-steps a new and distinct solution (where x is the input and p is a fixed polynomial). Interestingly, there is exists a class of incremental polynomial delay, , which contains problems that allow for enumeration algorithms whose delay increases in the process of computation. Intuitively, this captures the idea that after printing ‘obvious’ solutions, later in the process, it becomes difficult to find new outputs. More precisely, the delay between output i and is bounded by a polynomial in the input length and in i. Consequently, in the beginning, such an algorithm possesses a polynomial delay, whereas later, it eventually becomes exponential (for problems with exponentially many solutions, which is rather a common phenomenon). While prominent problems in the class are the enumeration of satisfying assignments for Horn or Krom formulas [5], the enumeration of structures for first-order query problems with possibly free second-order variables and at most one existential quantifier [6], or the enumeration of cycles in graphs [7], rather a limited amount of research has been invested in understanding . A well-studied problem in this enumeration complexity class is the task of generating all maximal solutions of systems of equations modulo 2 [8]. Even today, it is not clear whether this problem can be solved with a polynomial delay. Another example of problems in is the task to enumerate conjuncts in the context of monotone dualization of DNF formulas investigated by Eiter et al. [9], and Fredman and Khachiyan [10]. The significance of these results stems from the connection to computing minimal hypergraph transversals. A more recent result, which is not known to be in and not equivalent to the enumeration of transversals in hypergraphs of fixed edge size, was shown to be a member of by Carmeli et al. [11]: the task to enumerate all minimal triangulations of a given graph. In 2017, Capelli and Strozecki [12] investigated and its relationship to other classical enumeration classes in depth, greatly improving the overall understanding of incremental polynomial delay. One of their central results for this paper shows that if the function variant of restricted to total functions coincides with , then we have a collapse of incremental polynomial time with , the class of problems for which all solutions can be enumerated in time polynomial in the input length and in the solution set size (see Proposition 4 on page 4). Furthermore, Capelli and Strozecki studied exponent sliced versions of incremental time and showed that this hierarchy of classes strictly interleaves ([12], Proposition 16).

1.2. Parameterized Complexity

The framework of parameterized complexity [13,14,15,16] allows one to approach a fine-grained complexity analysis of problems beyond classical worst-case complexity. Here, one considers a problem together with a parameter and tries to achieve deterministic runtimes of the form , where is the value of the parameter of an instance x (note that the parameter does not depend on the input length), p is a polynomial, and f is an arbitrary computable function. Problems that can be solved by algorithms within these runtime bounds belong to the class . The class name abbreviates ‘fixed-parameter tractable’ and is justified by the observation that a relevant parameter is seen be slowly growing or even of constant value [17].

A rather large parameterized complexity class is -, the nondeterministic counterpart of , which is defined via nondeterministic runtimes of the same form of . By definition of the classes, the inclusion - is immediate. Nonetheless, compared to the situation on the classical complexity side, - is not seen as a counterpart of in the sense of intractability. In fact, is the class which usually is used to show intractability lower bounds in the parameterized setting. This class is part of an infinite -hierarchy in between the aforementioned two classes. It is not known whether any of the inclusions of the intermediate classes is strict or not.

1.3. Parameterized Enumeration

Recently, Creignou et al. [18,19,20,21] developed a framework of parameterized enumeration allowing for fine-grained complexity analyses of enumeration problems. In analogue to classical enumeration complexity, there are the classes and , and it is unknown if is true or not. Here, for problems in , enumeration algorithms exist which print solutions with a delay of the form , where t is a computable function, the parameterization, x the input, and i is the index of the currently printed solution. Similarly, problems in allow for enumeration algorithms running with an fpt-delay.

In their research, Creignou et al. [20] noticed that for some problems, enumerating solutions by increasing size is possible with and exponential space (such as triangulations of graphs, or cluster editings). However, it is not clear how to circumvent the unsatisfactory space requirement. Recently, Meier and Reinbold [22] observed a similar phenomenon. They studied the enumeration complexity of problems in a modern family of logics of dependence and independence. In the context of dependence statements, single assignments do not make sense. As a result, one introduces team semantics defining semantics with respect to sets of assignments, which are commonly called teams. Meier and Reinbold showed that in the process of enumerating satisfying teams for formulas of a specific Dependence Logic fragment, it seemed that an delay required exponential space in this particular setting. While reaching polynomial space for the same problem, the price was paid by an increasing delay, , and it was not clear how to avoid the increase of the delay while maintaining a polynomial space threshold. This is a significant question of research, and we improve the understanding of this question by pointing out connections to classical enumeration complexity where similar phenomena have been observed [12] (see also the discussion in the beginning of Section 4).

1.4. Related Work

In 1991, Megiddo and Papadimitriou [23] introduced the function complexity class and studied problems within this class. In a recent investigation, Goldberg and Papadimitriou introduced a rich theory around this complexity class that also features several aspects of proof theory [24]. Additionally, the investigations of Capelli and Strozecki [12] on probabilistic classes might yield further connections to the enumeration setting via the parameterized analogues of probabilistic computation of Chauhan and Rao [25]. Furthermore, Fichte et al. [26] studied the parameterized complexity of default logic and present in their work a parameterized enumeration algorithm outputting stable extensions. It might be worth further analyzing problems in this setting, possibly yielding algorithms. Quite recently, Bläsius et al. [27] considered the enumeration of minimal hitting sets in lexicographical order and devised some cases which allow for -, resp., -algorithms. Furthermore, Pichler et al. [28] showed enumeration complexity results for problems on MSO (monadic second order logic) formulas. Finally, investigations of Mary and Strozecki [29] are related to the -versus- question from the perspective of closure operations. Counting classes in the parameterized setting have been introduced by Flum and Grohe [30] as well as by McCartin [31]. Very recently, Roth and Wellnitz [32] presented a thorough study of counting and finding homomorphisms and showed how their results improve the understanding of the class # (the counting variant of ). The understanding of this class has been improved also by a line of previous research, e.g., the works of Curticapean, Dell, and Roth [33] as well as of Roth and Schmitt [34] (and more recently, together with Dörfler and Wellnitz [35]). The thesis of Curticapean [36] also presents a nice overview of this field.

1.5. Our Contribution

We improve the understanding of incremental enumeration time by connecting classical enumeration complexity to the very young field of parameterized enumeration complexity. Although we cannot answer the aforementioned time–space tradeoff question in either a positive or negative way, we hope that the presented “bridge” to parameterized enumeration will be helpful for future research. Capelli and Strozecki [12] distinguished two kinds of incremental polynomial time enumeration, which we call and . Essentially, the difference of these two classes lies in the perspective of the delay. For , one measures the delay between an output solution i and , which has to be polynomial in i and the input length. For , the output of i solutions has to be polynomial in i and the input length. This means that for the latter class, the output stream must not be as uniform as for the former. In Section 4, we introduce several parameterized function classes (a good overview of the classes can be found in Table 1 on page 11) that are utilized to prove our main result: if and only if (Corollary 4). This is the first result that directly connects the classical with the parameterized enumeration setting. Through this approach, separating the classical classes then implies separating the parameterized counterparts and vice versa. Moreover, we introduce two hierarchies of parameterized incremental time and (where is a class parameter that restricts the exponent of the polynomial for the solution index) in Section 3, show how they interleave and thereby provide some new insights into the interplay of delay and incremental delay. One of the previously mentioned parameterized function classes, -, is a counterpart of the class , the class of nondeterministic multivalued functions with values that are polynomially verifiable and guaranteed to exist, known from Megiddo and Papadimitriou [23]. For this class, the algorithmic task is to guess a witness y such that , where A is a total relation. It is important to note that this class summarizes significant cryptography-related problems such as factoring or the discrete logarithm modulo a (certified) prime p of a (certified) primitive root x of p (see the textbook of Talbot and Welsh [37] on cryptography-related problems). Clearly, parameterized versions of these problems are members in - via trivial parameterization .

Boiling down the presented results yields a list of equivalent collapse results and thereby connects a wealth of different fields of research: parameterized enumeration, classical enumeration, parameterized function complexity, classical function complexity, and computational complexity theory. Our second central result is summarized in Corollary 3 on page 15.

1.6. Outline

In Section 2, we introduce the necessary notions of parameterized complexity theory and (parameterized) enumeration algorithms. Then, we continue in Section 3 to present two hierarchies of parameterized incremental enumeration classes and study the relation to . Eventually, in Section 4, we introduce several parameterized function classes and outline connections to the parameterized enumeration classes. There, we connect a collapse of the two function classes - and to a collapse of and , extend this collapse to and (thus, in the classical function complexity setting), and further reach out for our main result showing if and only if . Finally, we conclude and present questions for future research.

2. Preliminaries

Enumeration algorithms are usually running in exponential time as the solution space is of this particular size. As Turing machines cannot access specific bits of exponentially sized data in polynomial time, one commonly uses the RAM model as the machinery of choice; see, for instance, the work of Johnson et al. [1] or, more recently, of Creignou et al. [38]. For our purposes, polynomially restricted RAMs (RAMs where each register content is polynomially bounded with respect to the input size) suffice. We make use of the standard complexity classes and . An introduction into this field can be found in the textbook of Pippenger [39].

2.1. Parameterized Complexity Theory

We present a brief introduction into the field of parameterized complexity theory. For a deeper introduction, we kindly refer the reader to the textbooks of Flum and Grohe [15], Niedermeyer [16], or Downey and Fellows [13].

Let be a decision problem over some alphabet . Given an instance , we call k the parameter’s value (of x). Often, instead of using tuple notation for instances, one uses a polynomial time computable function (the parameterization) to address the parameter’s value of an input x. Then, we write denoting the parameterized problem (PP).

Definition 1

(Fixed-parameter tractable). Let be a parameterized problem over some alphabet Σ. If there exists a deterministic algorithm A and a computable function such that for all

- A accepts x if and only if , and

- A has a runtime of ,

Then A is an fpt-algorithm for and is fixed-parameter tractable (or short, in the complexity class ).

Flum and Grohe [15] provide a way to “parameterize” a classical and robust complexity class. For our purposes, - suffices, and accordingly, we do not present the general scheme.

Definition 2

(-, ([15], Definition 2.10)). Let with be a parameterized problem over some alphabet Σ. We have - if there exists a computable function and a nondeterministic algorithm N such that for all , N correctly decides whether in at most steps, where p is a polynomial.

Furthermore, Flum and Grohe characterize the class - via all problems “that are in after precomputation on the parameter”.

Proposition 1

([15], Proposition 2.12). Let be a parameterized problem over some alphabet Σ. We have - if and only if there exists a computable function and a problem such that and the following is true: For all instances , we have that if and only if .

According to the well-known characterization of the complexity class via a verifier language, one can easily deduce the following corollary, which is later utilized to explain Definition 11.

Corollary 1.

Let be a parameterized problem over some alphabet Σ and p some polynomial. We have - if there exists a computable function and a problem such that and the following is true: For all instances , we have that if and only if there exists a y such that and .

2.2. Enumeration

As already motivated in the beginning of this section, measuring the runtime of enumeration algorithms is usually abandoned beyond the study of . As a result, one inspects the uniformity of the flow of output solutions of these algorithms rather than their total running time. In view of this, one measures the delay between two consecutive outputs. Johnson et al. [1] laid the cornerstone of this intuition in a seminal paper and introduced the necessary tools and complexity notions. Creignou, Olive, and Schmidt [3,40] presented recent notions in this framework, which we aim to follow. In this paper, we only consider enumeration problems which are “good” in the sense of polynomially bounded solution lengths and polynomially verifiable solutions (Capelli and Strozecki [12] call the corresponding class EnumP). A good textbook that introduces into the field of exact exponential algorithms is by Fomin and Kratsch [41].

Definition 3

(NP Enumeration Problem). An NP enumeration problem (EP) over an alphabet Σ is a tuple , where

- is the set of instances (recognizable in polynomial time),

- is a computable function such that for all , is a finite set and if and only if ,

- , and

- there exists a polynomial p such that for all and we have .

Furthermore, we use the shorthand to refer to the set of solutions for every possible instance. If is an EP over the alphabet , then we call strings instances of E, and the set of solutions of x.

An enumeration algorithm (EA) for the EP is a deterministic algorithm which, on the input x of E, outputs exactly the elements of without duplicates, and which terminates after a finite number of steps on every input. The following definition fixes the ideas of measuring the ‘flow of output solutions’.

Definition 4

(Delay). Let be an enumeration problem and be an enumeration algorithm for E. For , we define the i-th delay of as the time between outputting the i-th and -st solution in . Furthermore, we set the 0-th delay to be the precomputation phase, which is the time from the start of the computation to the first output statement. Analogously, the n-th delay, for , is the postcomputation phase, which is the time needed after the last output statement until terminates. If , then, generally, is said to output with delay if for all and all the i-th delay is in .

Subsequently, we use the notion of delay to state the central enumeration complexity classes.

Definition 5.

Let be an enumeration problem and be an enumeration algorithm for E. Then, is

- a --algorithm if and only if there exists a polynomial p such that for all , algorithm outputs in time .

- a -algorithm if and only if there exists a polynomial p such that for all , algorithm outputs with delay .

- an -algorithm if and only if there exists a polynomial p such that for all , algorithm outputs and its i-th delay is in (for every ).

- a -algorithm if and only if there exists a polynomial p such that for all , algorithm outputs i elements of in time (for every ).

- a -algorithm if and only if there exists a polynomial p such that for all , algorithm outputs in time .

Then, we say E is in -//// if E admits an --/-/-/-/-algorithm. Finally, we define .

Note that in the diploma thesis of Schmidt ([40], Section 3.1), the class - is called . We avoid this name to prevent possible confusion with class names defined in the following section as well as with the work of Capelli and Strozecki [12]. Additionally, we want to point out that Capelli and Strozecki use the definition of for (and use the name “” for instead). They prove that the notions of and are equivalent up to an exponential space requirement when using a structured delay. The idea for the following proposition is that we can wait to output previously computed solutions.

Proposition 2

([12], Corollary 13). Without any space restrictions we have that .

After studying the definition of the class , one could easily come to the opinion that the class is more general than because it does not necessarily have a uniform delay. However, the previous proposition told us that this is not true.

2.3. Parameterized Enumeration

Having introduced the basic principles in parameterized complexity theory and enumeration complexity theory, we introduce a combined version of these notions.

Definition 6

([19]). A parameterized enumeration problem (PEP) over an alphabet Σ is a triple , where

- is a parameterization (that is, a polynomial-time computable function), and

- is an EP.

The definitions of enumeration algorithms and delays are easily lifted to the setting of PEPs. Observe that the following defined classes are in complete analogy to the nonparameterized case from the previous section.

Definition 7

([19]). Let be a PEP and an enumeration algorithm for E. Then the algorithm is

- an -enumeration algorithm if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every instance , outputs in time at most ,

- a -algorithm if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every , outputs with delay of at most ,

- an -algorithm if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every , outputs and its i-th delay is at most , and

- an -algorithm if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every instance , outputs in time at most .

Note that, as before, the notion of has been used for the class of -enumerable problems [18]. We avoid this name as it causes confusion with respect to an enumeration class ([40], Section 3.1), which takes into account not only the size of the input but also the number of solutions. We call this class instead and, accordingly, it is the nonparameterized analogue of the above class . Now, we group these different kinds of algorithms in complexity classes.

The class /// is the class of all PEPs that admit an -enumeration/-/-/-algorithm.

The class captures a good notion of tractability for parameterized enumeration complexity. Creignou et al. [19] identified a multitude of problems that admit enumeration. Note that, due to Flum and Grohe ([15], Proposition 1.34) the class can be characterized via runtimes of the form either or (as , for all ). Accordingly, this applies also to the introduced classes , , and .

3. Interleaving Hierarchies of Parameterized Incremental Delay

The previous observations raise the question of how relates to . In the classical enumeration world, this question has been partially answered by Capelli and Strozecki ([12], Proposition 16) for a weaker capped version of incremental polynomial time: is true for the restriction to solution sets that do not necessarily obey the last two items of Definition 3 (they call this class ). Only for linear total time and polynomial space under this setting is the relation not completely understood, that is, the question how with polynomial space relates to with polynomial space ([12], Open Problem 1, p. 10).

In the course of this chapter, it is shown that the relationship between the classical and the parameterized world is very close. Capelli and Strozecki approach the separation mentioned above through the classes and prove a strict hierarchy of these classes. We lift this to the parameterized setting.

Definition 8

(Sliced Versions of Incremental FPT Delay, extending Definition 7). Let be a PEP and an enumeration algorithm for E. Then, algorithm is

- 3′.

- a -algorithm (for ) if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every , outputs i elements of in time (for every ).

- 3″.

- an -algorithm (for ) if there exists a computable function and a polynomial p such that for every , outputs and its i-th delay is at most .

Similarly, we define a hierarchy of classes for every which consist of problems that admit an -algorithm. Moreover, .

Clearly, and by Definition 7 as the i-th delay then merely is , as .

Usually, one utilizes a priority queue to store the already printed solutions as it allows for efficiently detecting duplicates. Nevertheless, it is unclear how to detect duplicates of solutions without storing them in the queue. Currently, it seems that the price of a “regular” (that is, polynomial) delay then is paid by the need for exponential space. Agreeing with Capelli and Strozecki ([12], Section 3), it seems very reasonable to see the difference of and anchored in the presence of an exponential sized priority queue. However, relaxing this statement shows that the equivalence of incremental delay and capped incremental -time is also true in the parameterized world. Similarly, as in the classical setting ([12], Proposition 12), the benefit of a structured delay can be reached with the exponential space of a priority queue. To lift the argumentation in the proof to the parameterized setting, one needs to keep track of the factors of the kind in the process. The remainder of the argumentation is the same.

Theorem 1.

For every , .

Proof.

“⊇”: Let be a PEP in via an algorithm . Let be a computable function and be a polynomial as in Definition 8 (3″). For every , algorithm outputs i solutions with a running time bounded by

Accordingly, we have that .

“⊆”: Now consider a problem via enumerating i elements of in time for all , for all , and some computable function t (see Definition 8 (3′)). We show that enumerating can be achieved with an i-th delay of , where and s bounds the solution sizes (which is polynomially in the input length; w.l.o.g. let p be an upper bound for this polynomial). This means that we argue on the duration of the i-th delay, which summarizes the time needed to find the i-th solution and to print it. To reach this delay, one uses two counters: one for the steps of (steps) and one for the solutions, initialized with value 1 (solindex). While simulating , the solutions are inserted into a priority queue instead of printing them. Eventually, the step counter reaches . Then, the first element of is extracted, output, and is incremented by one. In view of this, computed solindex many solutions and prints the next one (or already halted). Combining these observations leads to calculating the i-th delay:

Clearly, this is a delay of the required form , and thus, . □

Note that from the previous result, one can easily obtain the following corollary.

Corollary 2.

and .

If one drops the restrictions 3. and 4. from Definition 3, then Capelli and Strozecki unconditionally show a strict hierarchy for the cap-classes via utilizing the well-known time hierarchy theorem [42]. Of course, this result transfers also to the parameterized world, that is, to the same generalization of . Nonetheless, it is unknown whether a similar hierarchy can be unconditionally shown for these classes as well as for .

Open Problem 1.Can a similar hierarchy be unconditionally shown for these classes as well as for ?

This is a significant question of further research which is strengthened in the following section via connecting parameterized with classical enumeration complexity.

4. Connecting with Classical Enumeration Complexity

Capelli and Strozecki [12] ask whether a polynomial delay algorithm using exponential memory can be translated into an output polynomial or even incremental polynomial algorithm requiring only polynomial space. This question might imply a time–space tradeoff, that is, avoiding exponential space for a -algorithm will yield the price of an increasing delay. This remark perfectly reflects with what has been observed by Creignou et al. [20]. They noticed that outputting solutions ordered by their size seems to require exponential space in case one aims for . Nonetheless, the mandatory order is a strong additional constraint which might weaken the evidence of that result substantially. As mentioned in the introduction, Meier and Reinbold [22] observed how a algorithm with exponential space of a specific problem is transformed into an algorithm with polynomial space. These results emphasize what we strive for and why it is valuable to have such a connection between these two enumeration complexity fields. In this section, we prove that a collapse of and implies collapsing to and vice versa.

Capelli and Strozecki [12] investigated connections from enumeration complexity to function complexity classes of a specific type. The classes of interest contain many notable computational problems such as integer factoring, local optimization, or binary linear programming.

It is well known that function variants of classical complexity classes do not contain functions as members but relations instead. Accordingly, we formally identify languages and their solution-space with relations and thereby extend the notation of PPs, EPs, and PEPs. Nevertheless, it is easy to see how to utilize a witness function f for a given language L such that implies for some y such that is true (this means that for the kind of relations mentioned before), and “no” otherwise, in order to match the term “function complexity class” more adequately.

Definition 9.

We say that a relation is polynomially balanced if implies that for some polynomial p.

Recall that, for instances of a (P)EP E over , the length of its solutions is polynomially bounded. Accordingly, the underlying relation is polynomially balanced.

The following two definitions present four function complexity classes.

Definition 10

( and ). Let be a binary and polynomially balanced relation.

- if there is a deterministic polynomial time algorithm that, given , can find some such that is true.

- if there is a deterministic polynomial time algorithm that can determine whether is true, given both x and y.

Definition 11

( and -). Let be a parameterized and polynomially balanced relation with parameterization κ.

- if there exists a deterministic algorithm that, given , can find some such that is true and runs in time , where f is a computable function and p is a polynomial.

- - if there exists a deterministic algorithm that, given both x and y, can determine whether is true and runs in time , where f is a computable function and p is a polynomial.

Note that the definition of - follows the verifier characterization of precomputation on the parameter as observed in Corollary 1. Similarly to the classical decision class, , the runtime has to be independent of the witness length .

The next definition lifts the class [23] to the parameterized setting. Notice that the class definition incorporates two special markers (called a and b)—similar as in the classical setting—to differentiate between the two types of witnesses.

Definition 12

(--). Given a language , we say that -- if there exist two parameterized and polynomially balanced relations and with parameterizations κ and as well as a nondeterministic algorithm N such that the following two properties are fulfilled.

- For each , either there exists a y with , or there is a z with , where are two special markers in Σ.

- Given , N can find either a y with or a z with in time , or state that such ones do not exist, where are polynomials and are computable functions.

The typical problems in -- then ask for finding an appropriate witness (of ‘type’ either a or b) with respect to a given x. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Overview of function complexity classes. In the machine column, ‘det.’/‘nond.’ abbreviates ‘deterministic’/‘nondeterministic’. In the runtime column, p and q are polynomials, f and g are two computable functions, is the parameterization of A, is the parameterization of B, and x is the input.

In 1994, Bellare and Goldwasser [43] investigated functional versions of problems. They observed that under standard complexity-theoretic assumptions (deterministic doubly exponential time is different from nondeterministic doubly exponential time), such functional variants are not self-reducible (as the decision variant is). Here, a problem is self-reducible means that one constructs a witness in a bit-wise fashion, given an oracle for that problem. Bellare and Goldwasser noticed that these functional versions are harder than their corresponding decision variants.

A binary relation is said to be total if for every there exists a such that .

Definition 13

(Total function complexity classes). (resp., -) is the restriction of (resp., -) to total relations.

The two previously defined classes are promise classes in the sense that the existence of a witness y with is guaranteed. Furthermore, defining a class or is not meaningful as it is known that (see, e.g., the work of Johnson et al. ([44], Lemma 3) showing that is contained in , polynomial local search, which is contained in by Megiddo and Papadimitriou ([23], p. 319). Similar arguments apply to -).

Now, we can define a generic (parameterized) search and a generic (parameterized) enumeration problem. Note that the parameter is only relevant for the parameterized counterpart named in brackets.

| Problem: | (-AnotherSolA), where |

| Input: | , . |

| Parameter: | . |

| Task: | output y in , or answer . |

| Problem: | (-)Enum-A, where |

| Input: | . |

| Parameter: | . |

| Output: | output all y with . |

The two results of Capelli and Strozecki ([12], Propositions 7 and 9) which are crucial in the course of this section are restated in the following.

Proposition 3

([12], Proposition 7). Let be a binary relation such that, given , one can find a y with in deterministic polynomial time. Then the following is true: AnotherSolA ∈ if and only if Enum-.

Proposition 4

([12], Proposition 9). if and only if .

In 1991, Megiddo and Papadimitriou studied the complexity class [23]. In a recent investigation, Goldberg and Papadimitriou introduced a rich theory around this complexity class that also features several aspects of proof theory [24]. Megiddo and Papadimitriou prove that the classes and coincide. Their arguments are easily lifted to the parameterized setting.

Theorem 2.

---.

Proof.

We reformulate the classical proofs of Megiddo and Papadimitriou [23].

“⊆”: By definition of the class --, either there exists a y with , or there is a z with . As a result, the mapping suffices and is total as either of the two witnesses always exists (see Definition 12). Thus, one just needs to guess which of A or B to choose.

“⊇”: the mapping from the total relation A to meets the requirements of -- as only one type of witnesses is needed, and for every x, there is a y such that as A is total by assumption. □

For the following Lemma 1 (which is the parameterized pendant of Proposition 3) and theorem, we follow the argumentation in the proofs of the classical results (Propositions 3 and 4). They underline the interplay between search and enumeration.

Lemma 1.

Let be a parameterized problem with parameterization κ. Then,-AnotherSolA ∈ if and only if -Enum-.

Proof.

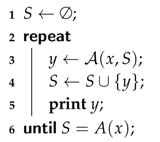

“⇒”: Let -AnotherSolA ∈ via some algorithm . Algorithm 1 shows that -Enum-.

The runtime of each step is for some polynomial p and some computable function f. Consequently, this shows that -Enum-.

“⇐”: Let -Enum-. Then, there exists a parameterized enumeration algorithm that, given input , outputs elements in a runtime of for some computable function f, , and a polynomial p.

Now, we explain how to compute -AnotherSolA in fpt-time. Given , simulate for steps. If the simulation successfully halts, then is completely output. Just search a or output “”. Otherwise, if did not halt, then it did output at least different elements. Finally, we just compute and print a new element. □

| Algorithm 1: Algorithm showing -Enum-. |

|

The next theorem translates the result of Proposition 4 from classical enumeration complexity to the parameterized setting. It shows the first connection of parameterized enumeration to parameterized function complexity.

Theorem 3.

- if and only if .

Proof.

“⇐”: Let - be a parameterized language over with parameterization . Furthermore, let M denote the nondeterministic algorithm that guesses the witnesses y and then verifies with the deterministic algorithm as in Definition 11. Additionally, denote the running time of M by for a polynomial p, a computable function g, and an input x. Now, define the relation , where , such that

Then, for each x there exists such that is true by the definition of the class -. Moreover, via padding, for each x, there exist at least solutions z such that is true; in particular, z is of the form such that is true. Notice that the total length of is bounded by as y already has the length constraint of by the - requirement. By construction, the trivial brute-force enumeration algorithm checking all is in time for every element of . Accordingly, this gives -Enum- as the runtime for algorithms encompasses as a factor.

Then, -Enum- and the first is output in time . Since A was arbitrary, we conclude with - (as - by definition).

“⇒”: Consider a problem -Enum- with -Enum-. For every and let be true if and only if either () or ( and ). Then, -:

- D is total by construction,

- as -Enum- is a PEP, there exists a polynomial q such that for every solution we have that , and

- finally, we need to show that can be verified in deterministic time for a computable function f and a polynomial p.

- Case :

- is true if and only if . This requires testing whether and . Both can be tested in polynomial time: , respectively, which follows from Definition 7 (4.).

- Case :

- is true if and only if . As -Enum-, there is a deterministic algorithm outputting in steps. Now, run for at most steps. Then, finishing within this steps-bound implies that is completely generated, and we merely check in time polynomial in . If did not halt within the steps-bound, we can deduce . Accordingly, follows and is not true.

As - is true by precondition, given a tuple , we either can compute a y with or decide there is none (and then set ) in time . Accordingly, -AnotherSolA is in and, by applying Lemma 1, we get -Enum- is in . This settles that and concludes the proof. □

The next theorem connects a collapse in the classical function world to a collapse in the parameterized function world. It witnesses the first connection between a collapse in classical and one in parameterized function complexity.

Theorem 4.

- if and only if .

Proof.

Let us start with the easy direction.

“⇒”: Let be a total relation in . By definition of and -, -, where is the trivial parameterization assigning to each the zero 0. Since -, there exists a computable function , a polynomial p, and a deterministic algorithm , that, given the input , outputs some such that in time . As for each x, for each x and runs in polynomial time. Accordingly, we have and thereby as A was chosen arbitrarily.

“⇐”: Choose some - via the nondeterministic machine M running in time for a polynomial p, a computable function f, a parameterization , and an input x. By Proposition 1, we know that there exists a computable function and a problem such that and the following is true: for all instances and all solutions , we have that if and only if .

As B is total, is total with respect to the third argument as well. It follows by assumption that is also in via some deterministic machine having a runtime bounded by a polynomial q in the input length. Accordingly, we can define a deterministic machine for B which, given input , computes , then simulates on , and runs in time

where is a computable function that estimates the runtime of computing . Clearly, Equation (1) is an fpt-runtime witnessing . Accordingly, we can deduce that -, as B was chosen arbitrarily. □

Combining Theorem 3 with Theorem 4 and finally Proposition 4 connects the parameterized enumeration world with the classical enumeration world. The following corollary summarizes deducible connections of parameterized enumeration to classical enumeration, parameterized function complexity, classical function complexity, and decision complexity. This means that a collapse of to would yield a collapse of to (Proposition 4) and as well as of to (due to [23]).

Corollary 3.

The following collapses are equivalent:

- -

If one does not consider space requirements—which is usually the case for these classes—we can deduce the following corollary by applying Corollary 2 and Proposition 2.

Corollary 4.

Without space requirements, we have that if and only if .

Now, we have seen that the observations made by Capelli and Strozecki [12] can be directly transferred to the parameterized setting. In cryptography, one-way functions are functions that are easily (in polynomial time) to compute but hard to invert (often, this means either it requires exponential time to invert the function, or, in a probabilistic model, the search space is of exponential size wherefore the success probability to invert the function is very low). A good introduction to this topic is given by Talbot and Welsh [37]. As a result of Corollary 3 together with Corollary 4, for instance, the existence of one-way functions would separate from as well.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

We presented the first connection of parameterized enumeration to classical enumeration by showing that a collapse of to implies collapsing to and vice versa. While proving this result, we showed equivalences of collapses of parameterized function classes developed in this paper to collapses of classical function classes. In particular, we proved that - if and only if (Theorem 4). The function complexity class , which has - as its parameterized counterpart, contains significant cryptography-related problems such as factoring. Furthermore, we studied a parameterized incremental time enumeration hierarchy on the level of exponent slices (Definition 8) and observed that (Corollary 2). Additionally, an interleaving of the two hierarchies, and , has been shown (Theorem 1). The results of this paper underline that parameterized enumeration complexity is an area worth studies, as there are deep connections to its classical counterpart.

Future research should build on these classes to unveil the presence of exponential space in this setting and give a definite answer to the observed time–space tradeoffs of versus . Can the hierarchy introduced and studied in Section 3, be shown strict under similar conditions as Capelli and Strozecki were able to prove (they used the exponential time hypothesis)? Moreover, it would be engaging to study connections from parameterized enumeration to proof theory via the work of Goldberg and Papadimitriou [24]. We want to close with the question of whether there exist intermediate natural problems between and - which are relevant in some area beyond trivial parameterization .

Funding

This research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ME 4279/1-2).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Maurice Chandoo (Hannover), Johannes Fichte (Dresden), Martin Lück (Hannover), Johannes Schmidt (Jönköping), and Till Tantau (Lübeck) for various discussions about topics of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Johnson, D.S.; Papadimitriou, C.H.; Yannakakis, M. On Generating All Maximal Independent Sets. Inf. Process. Lett. 1988, 27, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, D.; Fukuda, K. Reverse Search for Enumeration. Discrete Appl. Math. 1996, 65, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Olive, F.; Schmidt, J. Enumerating All Solutions of a Boolean CSP by Non-decreasing Weight. In Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference, SAT 2011, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 19–22 June 2011; Sakallah, K.A., Simon, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Volume 6695, pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozecki, Y. On Enumerating Monomials and Other Combinatorial Structures by Polynomial Interpolation. Theory Comput. Syst. 2013, 53, 532–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Hébrard, J.J. On generating all solutions of generalized satisfiability problems. Theor. Inform. Appl. 1997, 31, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Strozecki, Y. Enumeration Complexity of Logical Query Problems with Second-order Variables. In Computer Science Logic, Proceedings of the 25th International Workshop/20th Annual Conference of the EACSL, CSL 2011, Bergen, Norway, 12–15 September 2011; Bezem, M., Ed.; Schloss Dagstuhl—Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2011; Volume 12, pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, R.C.; Tarjan, R.E. Bounds on backtrack algorithms for listing cycles, paths, and spanning trees. Networks 1975, 5, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachiyan, L.G.; Boros, E.; Elbassioni, K.M.; Gurvich, V.; Makino, K. On the Complexity of Some Enumeration Problems for Matroids. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 2005, 19, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiter, T.; Gottlob, G.; Makino, K. New Results on Monotone Dualization and Generating Hypergraph Transversals. SIAM J. Comput. 2003, 32, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, M.L.; Khachiyan, L. On the Complexity of Dualization of Monotone Disjunctive Normal Forms. J. Algorithms 1996, 21, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, N.; Kenig, B.; Kimelfeld, B. Efficiently Enumerating Minimal Triangulations. In Proceedings of the 36th ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGAI Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS 2017), Chicago, IL, USA, 14–19 May 2017; Sallinger, E., den Bussche, J.V., Geerts, F., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, F.; Strozecki, Y. Incremental delay enumeration: Space and time. Discret. Appl. Math. 2019, 268, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, R.G.; Fellows, M.R. Fundamentals of Parameterized Complexity; Springer: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, R.G.; Fellows, M.R. Parameterized Complexity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flum, J.; Grohe, M. Parameterized Complexity Theory; Texts in Theoretical Computer Science. An EATCS Series; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, R. Invitation to Fixed-Parameter Algorithms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alber, J.; Fernau, H.; Niedermeier, R. Parameterized complexity: Exponential speed-up for planar graph problems. J. Algorithms 2004, 52, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Meier, A.; Müller, J.; Schmidt, J.; Vollmer, H. Paradigms for Parameterized Enumeration. In Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science 2013, Proceedings of the 38th International Symposium, MFCS 2013, Klosterneuburg, Austria, 26–30 August 2013; Chatterjee, K., Sgall, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Volume 8087, pp. 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Meier, A.; Müller, J.; Schmidt, J.; Vollmer, H. Paradigms for Parameterized Enumeration. Theory Comput. Syst. 2017, 60, 737–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Ktari, R.; Meier, A.; Müller, J.; Olive, F.; Vollmer, H. Parameterized Enumeration for Modification Problems. In Language and Automata Theory and Applications, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference, LATA 2015, Nice, France, 2–6 March 2015; Dediu, A., Formenti, E., Martín-Vide, C., Truthe, B., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 8977, pp. 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creignou, N.; Ktari, R.; Meier, A.; Müller, J.; Olive, F.; Vollmer, H. Parameterised Enumeration for Modification Problems. Algorithms 2019, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Reinbold, C. Enumeration Complexity of Poor Man’s Propositional Dependence Logic. In Foundations of Information and Knowledge Systems, Proceedings of the 10thInternational Symposium, FoIKS 2018, Budapest, Hungary, 14–18 May 2018; Ferrarotti, F., Woltran, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Megiddo, N.; Papadimitriou, C.H. On Total Functions, Existence Theorems and Computational Complexity. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1991, 81, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, P.W.; Papadimitriou, C.H. Towards a Unified Complexity Theory of Total Functions. Electron. Colloq. Comput. Complex. (ECCC) 2017, 24, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Rao, B.V.R. Parameterized Analogues of Probabilistic Computation. In Algorithms and Discrete Applied Mathematics, Proceedings of the First International Conference, CALDAM 2015, Kanpur, India, 8–10 February 2015; Ganguly, S., Krishnamurti, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 8959, pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichte, J.K.; Hecher, M.; Schindler, I. Default Logic and Bounded Treewidth. In Language and Automata Theory and Applications Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, LATA 2018, Ramat Gan, Israel, 9–11 April 2018; Klein, S.T., Martín-Vide, C., Shapira, D., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Volume 10792, pp. 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläsius, T.; Friedrich, T.; Meeks, K.; Schirneck, M. On the Enumeration of Minimal Hitting Sets in Lexicographical Order. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.01310. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, R.; Rümmele, S.; Woltran, S. Counting and Enumeration Problems with Bounded Treewidth. In Logic for Programming, Artificial Intelligence, and Reasoning, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference, LPAR-16, Dakar, Senegal, 25 April–1 May 2010; Clarke, E.M., Voronkov, A., Eds.; Revised Selected Papers; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 6355, pp. 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.; Strozecki, Y. Efficient Enumeration of Solutions Produced by Closure Operations. In Proceedings of the 33rd Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science (STACS 2016), Orléans, France, 17–20 February 2016; Ollinger, N., Vollmer, H., Eds.; Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs). Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2016; Volume 47, pp. 52:1–52:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flum, J.; Grohe, M. The Parameterized Complexity of Counting Problems. SIAM J. Comput. 2004, 33, 892–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartin, C. Parameterized counting problems. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2006, 138, 147–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Wellnitz, P. Counting and Finding Homomorphisms is Universal for Parameterized Complexity Theory. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA 2020), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 5–8 January 2020; Chawla, S., Ed.; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 2161–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curticapean, R.; Dell, H.; Roth, M. Counting Edge-injective Homomorphisms and Matchings on Restricted Graph Classes. Theory Comput. Syst. 2019, 63, 987–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Schmitt, J. Counting Induced Subgraphs: A Topological Approach to #W[1]-hardness. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Parameterized and Exact Computation (IPEC 2018), Helsinki, Finland, 20–24 August 2018; Paul, C., Pilipczuk, M., Eds.; Schloss Dagstuhl—Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2018; Volume 115, pp. 24:1–24:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, J.; Roth, M.; Schmitt, J.; Wellnitz, P. Counting Induced Subgraphs: An Algebraic Approach to #W[1]-hardness. In Proceedings of the 44th International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science (MFCS 2019), Aachen, Germany, 26–30 August 2019; Rossmanith, P., Heggernes, P., Katoen, J., Eds.; Schloss Dagstuhl—Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2019; Volume 138, pp. 26:1–26:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curticapean, R. The Simple, Little and Slow Things Count: On Parameterized Counting Complexity. Ph.D. Thesis, Saarland University, Saarbrücken, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, J.M.; Welsh, D.J.A. Complexity and Cryptography—An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creignou, N.; Kröll, M.; Pichler, R.; Skritek, S.; Vollmer, H. On the Complexity of Hard Enumeration Problems. In Language and Automata Theory and Application, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, LATA 2017, Umeå, Sweden, 6–9 March 2017; Drewes, F., Martín-Vide, C., Truthe, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10168, pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippenger, N. Theories of Computability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J. Enumeration: Algorithms and Complexity. Master’s Thesis, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Hanover, Germany, 2009. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.582.8008&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Fomin, F.V.; Kratsch, D. Exact Exponential Algorithms; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmanis, J.; Stearns, R.E. On the computational complexity of algorithms. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1965, 117, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellare, M.; Goldwasser, S. The Complexity of Decision Versus Search. SIAM J. Comput. 1994, 23, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.S.; Papadimitriou, C.H.; Yannakakis, M. How Easy is Local Search? J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1988, 37, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).