1. Introduction

Forests are critical for ensuring biodiversity and are essential for a wide range of ecosystem services that are important to human well-being [

1]. Biodiversity plays a key role in forest ecosystem services. Wildlife is an important part of biodiversity and a source of food and entertainment. However, forest and wildlife resources are disappearing around the world at an alarming rate. The pressures brought on by human activities has led to the loss, fragmentation, and degradation of forests [

2], which has led to a significant reduction in and homogenization of biodiversity [

3,

4]. These declining trends are expected to continue [

4], especially in the rich forests of Central and South America, South and Southeast Asia, and Africa [

5]. The reduction of biodiversity caused by forest degradation not only causes serious ecological problems, but also threatens the livelihood of rural areas and has adverse effects on the food, energy, and health security of nearby communities [

6]. The chain reaction brought about by the decrease in biodiversity will also lead to land degradation, decline in soil fertility, and loss of tourism opportunities, which greatly limits poverty alleviation in rural areas [

7].

In the protection of wildlife and plants, scientific knowledge is an effective tool, which is usually related to protection methods and means—including monitoring, forecasting, and communication—such as precise early-warning system based on data and modeling [

8]. Although the importance of scientific knowledge is widely recognized, its role in society and its relationship with society are currently undergoing a critical examination [

9]. People increasingly realize that technology and data alone are not enough to improve people’s lives, because scientific knowledge cannot always provide accurate diagnosis or solutions for local people [

10]. Due to the complex and different characteristics of communities, people’s local knowledge and practice should also be considered based on their background and needs [

11].

Traditional indigenous people mainly live in areas rich in biodiversity. Their environment is closely related to their survival and development and is directly related to the protection and sustainable biodiversity [

12]. Therefore, they usually have a profound and comprehensive understanding of conservation and sustainable utilization. For centuries, rural communities have relied on local knowledge to protect their environment [

13]. Through learning, imitating, and observing from experience, rural people have formed a set of knowledge systems for forest and wildlife conservation [

14]. These practices, which are based on indigenous knowledge, play an irreplaceable role in protecting the biodiversity and morphological and functional integrity of forests and their associated ecosystems, while continuing to sustain rural livelihoods [

15]. For hundreds of years, indigenous knowledge and its application have sustained the livelihood, culture, forests, and agricultural resources of local communities [

16]. This knowledge is closely intertwined with traditional religious beliefs, customs, folklore, and land-use practices. It is dynamic and evolves with changes in environmental, social, economic, and political conditions [

17]. The application of indigenous knowledge helps to ensure that forest and wildlife resources continue to provide goods and services for present and future generations [

18].

The application of indigenous knowledge to forest and wildlife conservation has received increasing attention in recent years [

15,

19,

20,

21]. The inheritance and innovation of indigenous knowledge is regarded as the key to maintaining indigenous people’s traditions and protecting global biodiversity [

22]. However, faced with rapid social and economic developments, indigenous knowledge is becoming vulnerable to external forces; in fact, it has been lost in many parts of the world. Some of the remaining knowledge is only used by older generations and is not being passed on to younger generations. The loss of such knowledge represents the loss of a part of biodiversity. Therefore, it is imperative to document indigenous knowledge and find a way to maintain and innovate it.

This study intends to stir up academic discussion to address the role of indigenous knowledge in forest and wildlife conservation using a case study on the Bulang people in Yunnan Province, southwestern China. While recording indigenous knowledge of great significance for biodiversity conservation, the study also seeks to analyze the reasons why indigenous knowledge can play a role in forest and wildlife conservation. In the Results and Discussion sections of this paper, we document how local people use their indigenous knowledge to protect forests and wildlife and discuss why indigenous knowledge is effective in forest and wildlife conservation. Further, we describe the new dilemma faced by indigenous knowledge when bird-watching tourism is on the rise. In the conclusion section, some policy recommendations are proposed to deal with the problems faced by indigenous knowledge.

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of the Study Location

The research area of this study was located in the Mangba community, Cizhulin administrative village, Simaogang Town, Simao District, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province (

Figure 1). It is ~114 km away from Pu’er City, the municipal administrative center, and more than 40 km away from the nearest market. Mangba is located on a gentle slope in the upper part of a southeast northwest trending ridge with a 1500–1700 m mountain elevation. The valley bottom toward the northeast of the village corresponds to the Mangba River, while the valley toward the south corresponds to the Tanggai River. Toward the west lies the Nuozhadu provincial nature reserve. The main vegetation types include Simao Pine (

Pinus kesiya), mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest, and shrubs. The valley area corresponds to a secondary broad-leaved forest (

Figure 2). Scattered paddy fields and cultivated land can be found in the valley and on the hillside and slash-and-burn practices are followed for cultivating the slopes.

The history of this village dates back to 1100 years. It was controlled by the Han people (central government) and Dai people (local government) alternately. However, it has always been the residence of the Bulang people. If outsiders want to obtain the right of residence, they need to be recognized by most of the villagers. In order to get married to local Bulang people, outsiders need to obtain the consent of their parents and agree with their national values, which implies that the local people have a high sense of national identity. At present, there are 60 households in the village. Except for two Han households, the remaining belong to Bulang people and almost all households have more than two children. The Bulang language is the lingua franca among the villagers and Mandarin (official Chinese language) is not as widely used. When interacting with outsiders, some of the elderly and women from the village still cannot speak Mandarin fluently. The livelihood of the villagers is mainly based on the cultivation and collection of pine resin from around the village. The main crops are rice and corn; in addition to these crops, the villagers also raise pigs, chickens, ducks, and bees to produce honey. In 1996, the Nuozhadu Nature Reserve was established close to the village. More than 400 hectares of forest land and 70% of the village’s arable land were included in the reserve. It is forbidden to manage and cultivate this land, which further limits the livelihood resources of the villagers and forces half of the young people in the village to go out to work for a higher income.

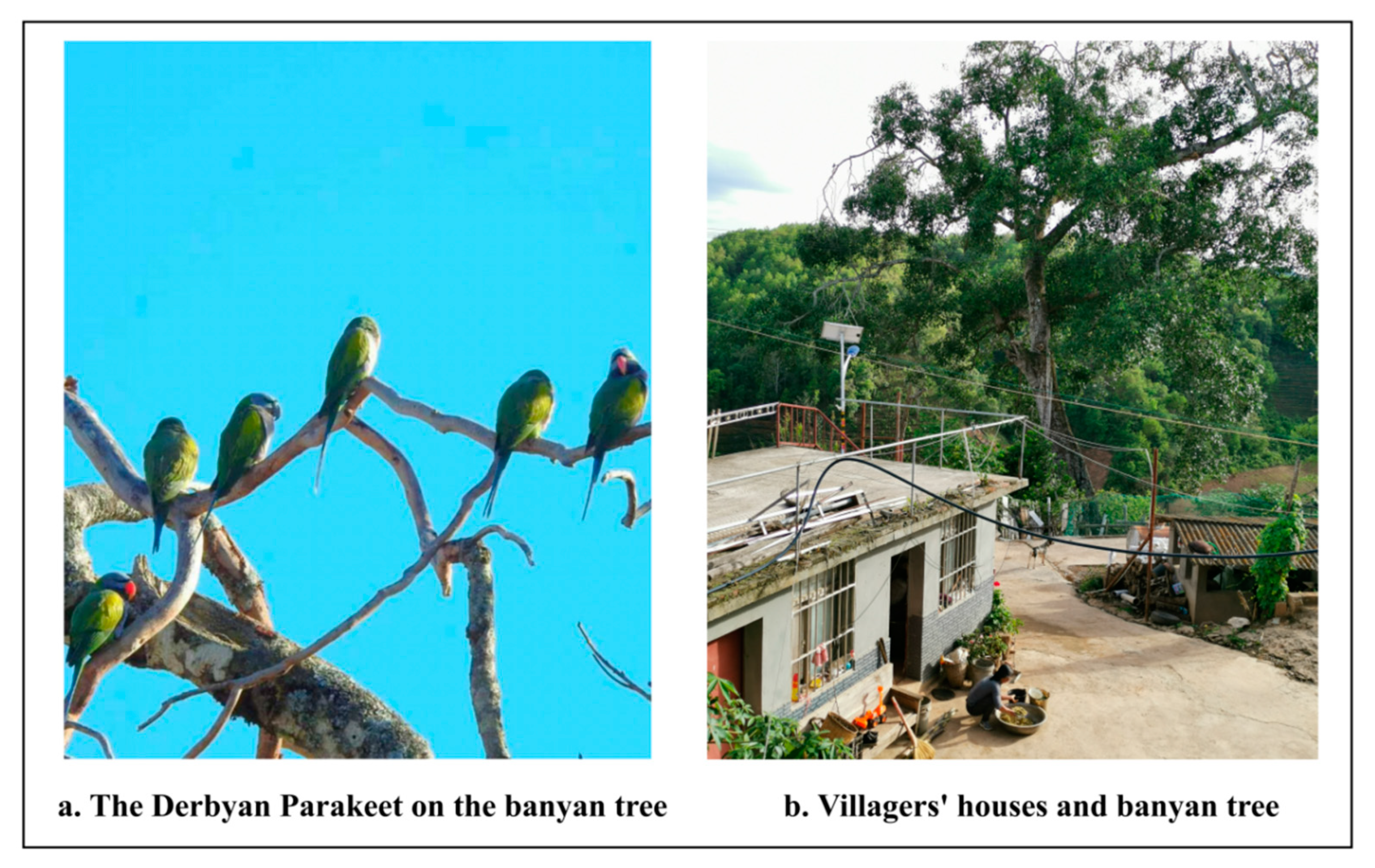

There are several large trees (mainly banyan) around the village (

Figure 2). The Derbyan Parakeet nests, lays eggs, and broods in the holes of these big trees, which also act as night habitats for parrots. These trees are close to the villagers’ houses with the nearest one being less than 5 m away (

Figure 3). The height of these trees is between 15–30 m with a diameter at breast height (DBH) of 500–2000 mm.

Eucalyptus and pine trees are the main forest resources of this village. In history, pine trees were a very important means of production for the local Bulang villagers. The local people have maintained the habit of collecting pine oleoresin for many years. Up to now, each household still has 20–40 acres of pine trees. However, the revenue of pine oleoresin collection is not continuous year by year. In some years, as not to affect the growth of pine trees, it is necessary to stop collection for the natural recovery of pine trees. In recent years, villagers rarely go to collect pine oleoresin. Because on the one hand, the price of pine oleoresin has fallen, the economic benefits of collecting pine oleoresin have become lower; on the other hand, some people have begun to engage in work related to bird-watching tourism and have no spare time to collect it.

Eucalyptus is mainly a timber forest, which is mainly distributed on the edge of the village, or outside the village. Most eucalyptus trees are contracted by companies for papermaking. A small number of villagers and these companies jointly buy shares to obtain profit dividends. In general, the local villagers use eucalyptus less, and their economic dependence on it is relatively low too.

2.2. Data Collection

The main research methods used in this investigation were key informant interviews, group discussions, participant observation, and secondary data collection. Interviews were the primary sources of data because of their epistemological tenets using which the experiences of the respondents could be understood better through expressed subjective narratives [

23]. The interviews proved useful as they gave voice to the relationship between the villagers, forests, and wildlife. The details about the research are listed in

Table 1.

The study started with a quick interview of the village leaders to collect and document forest and wildlife-related folk stories, religious beliefs, and traditional cultural practices. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants and selected household surveys were conducted in the village. These included village elders, village heads, Longtou (the host of the sacred tree worship ceremony), forest rangers employed by the local government, and operators of birdwatching tours in the village. Many of these informants were storytellers, participants in natural resource management, and active participants in religious activities; they were able to offer rich explanations of natural and historic events, sacred and productive forests, village regulations, and the wild-animal-protection measures adopted by the villagers. Six households were randomly selected and we worked extensively with these families using a semi-structured questionnaire to understand the interrelationship between their livelihoods and the forest and wildlife (especially the Derbyan Parakeet).

Two focus group discussions were held with villagers. The participants included 11 men and 9 women aged between 38 and 72 years. They were selected by the village leader on the basis of their rich indigenous knowledge and participation in cultural ceremonies and rituals. In addition, two birdwatching tour operators participated in the group discussion. Under our guidance, these groups created natural resource maps and historical timetables of the village, recording the most important events related to wildlife and forest resources. With the assistance of visual and participatory tools, rich information was gathered on the conservation of wildlife and forest resources.

In the key informant interviews and group discussions, the interview questions were divided into three parts, each with a specific goal. The purpose of the first part is to collect the indigenous knowledge about forest and wildlife conservation that each respondent knows. Each respondent was asked to describe the folktales, religious beliefs, and traditional culture and customs. At the same time, they were asked to describe their participation, such as whether they participated in sacrificial activities, whether they believed in the legend of sacred trees and birds. In addition, respondents were also asked to answer about the inheritance of indigenous knowledge. The second part aims to analyze the mechanism of indigenous knowledge. The respondents were first asked whether the indigenous knowledge such as nature worship and rural regulations or conventions had effectively protected forests and wildlife. Then, respondents needed to express their understanding of “why indigenous knowledge can restrain villagers’ behaviors”. At the end of the interview, questions such as “whether the development of birdwatching tourism benefits from indigenous knowledge” and “whether birdwatching tourism complies with indigenous knowledge” were raised to understand villagers’ views on indigenous knowledge after the rise of bird watching tourism.

4. Discussion

The case study presented here demonstrates that the Bulang people in Mangba have formed their own body of knowledge about nature and a code of conduct toward animals and plants. They have formed their own systems of animal and plant protection and management. Their indigenous knowledge constitutes of the social and religious values of the community, which are generally accepted in protecting the environmental system [

28]. This indigenous knowledge is inherited from ancestors and developed from generation to generation through rituals, stories, customs, and moral constraints. A notable custom is the annual Water-Splashing Festival. This popular annual ceremony is attended by everyone in the village. The worship of sacred trees during the ceremony also helps in maintaining the sanctity of banyan trees, ensures the inheritance of indigenous knowledge between generations, and protects biodiversity. In addition, the stories and folklore circulated in the village emphasize the relationship between human beings and the natural environment and strongly lean toward protecting biodiversity.

It is worth noting that there are no specific punishment measures in Mangba’s customary laws on the protection of wild animals and plants. It relies only on the moral constraints formed by society and kinship. However, the restraint effect is very obvious as well as the protection effect. This is due to the inconvenience in communication between the village and outside world; the daily lives and work of the villagers revolve around their immediate surroundings and hence their social network is relatively narrow. Once someone violates the values recognized by the villagers, he/she is severely condemned. This reduced the trust imposed by other villagers in this person and affects his/her normal life, weddings, funerals, and other activities. However, the income from selling parrots and felling banyan trees is not enough to eliminate the closed social space and compensate for the loss caused by the damage to social relations. Therefore, no one in the village dares to violate the village rules and regulations. This behavior is also related to the traditional “Tou Ren” management system of the Bulang nation. Before the Communist Party of China came into power, most of the Bulang people in Yunnan Province practiced the Tou Ren system, where the Tou Ren is the village manager instituted by the local feudal regime. Most such Tou Rens are senior citizens in the village. A Bulang village is an independent unit in politics and economy and is also the basic organization unit of the Bulang society [

29]. Each village and community is independent of each other. In the village, the head enjoys great prestige, respect, and power. He is responsible for organizing the worship ceremony, production activities, maintaining public order, and many other matters in the village [

30]. Therefore, the indigenous knowledge recognized by the leader is respected by the villagers and forms the common value orientation and identity. This ensures the inheritance and effective play of village rules and regulations in the long run.

The Mangba Bulang people’s indigenous knowledge on forest and wildlife protection is not unique to the Bulang ethnic group. Most of the areas in China where the Bulang people live have low productivity and backward production technology. They still use the slash-and-burn cultivation method and are very dependent on natural conditions [

31]. It is this kind of strong dependence on nature that forms the basis of the Bulang people’s fear and awe of nature, resulting in nature worship and customs on being close to and protecting nature. Because of the differences in natural environment, the scope of specific worship objects and protection objects is different [

32,

33]. For example, in Jingmai, another village inhabited by Bulang people in Pu’er City, the villagers worship tea trees and regard tea as their ancestral totem. On the basis of long-term exploration of the growth habits of tea trees and use of natural forests for shade, a method has been developed to cultivate tea in natural forests. Therefore, this region not only has more than 30 ancient tea gardens with more than 800 years of operational history, but also much higher biodiversity than the surrounding areas [

34]. Similarly, the Bulang people of Man’e village in Xishuangbanna City, Yunnan Province, think that an ancient tree in the southwest of the village is the residence of gods and hence do not touch it. Gods live not just on one tree but move frequently and therefore, people should be careful when cutting down trees. If a rare tree needs to be cut down, a wizard should be consulted [

29]. According to Dharma scriptures, cutting down trees results in some punishments. For example, cutting down rare trees or trees along the river can easily offend gods and lead to disasters. It is this fear that keeps some rare trees in the area alive. If we enlarge the perspective of other ethnic groups and regions in China, we can find that indigenous knowledge plays an important role in the sustainable utilization of natural resources and protection of wild animals and plants. For example, Yi people integrate traditional forest management practices into their religious activities, folklore, songs, and funeral customs [

17]. The protection of the Buyi Fengshui forest is also based on oral knowledge handed down from generation to generation. There are many rules and regulations designed and implemented by local people to protect the Fengshui forest. As a “community-based nature reserve”, the Fengshui forest is essential to the health of natural forests, especially hydrological characteristics and soil-erosion prevention [

35].

In modern times, biodiversity conservation is based on scientific knowledge. Many ecological conservation projects implemented in China restore the ecosystem and biodiversity based on scientific calculations and measurements. Many scholars have systematically evaluated them from the perspective of scientific knowledge [

36,

37]. However, in the early stages of this process, mainstream research believed that indigenous knowledge was unimportant, leading to a trend of marginalization of indigenous knowledge [

38,

39,

40]. Yet, knowledge systems rarely develop in isolation, because they usually tend to influence and benefit from each other. In this regard, we believe that indigenous knowledge and scientific knowledge are equally important and must be combined through a variety of methods to promote the development of biodiversity conservation. Indigenous knowledge is neither single nor immutable, but a large, diverse, and highly localized source of wisdom. Integrating this unique and specific indigenous knowledge system into other scientific knowledge basic systems may be one of the best ways to implement biodiversity conservation policies and behaviors more effectively and sustainably in indigenous communities in this study.

However, in the context of rapid socio-economic changes taking place in communities, local practices related to forest and wildlife conservation are vulnerable to many external forces. These include government policies and regulations that ignore the importance of indigenous knowledge, expansion of an increasingly globalized market economy in previously self-sufficient rural areas, infrastructure development, and extensive access to mass media. All of these have led to a general erosion of indigenous knowledge, decline in the power of moral constraints, and a decline in the interest of the younger generation in traditional wisdom, knowledge, and lifestyle.

Due to the vulnerability of indigenous knowledge-based practices, they face marginalization, dilution, transformation, or even being forgotten in rural communities in many lands. Therefore, it is necessary to record indigenous knowledge, analyze its mechanism of action, and ensure their inheritance and development. The rise of birdwatching tourism in Mangba village has not only increased the local economic income and employment opportunities, but also made the local people reexamine their attitude and behavior toward resources, environment, and wildlife. More importantly, it has reestablished the interest of local people in indigenous knowledge and recognize its value. This shows that it is helpful to let people in rural communities fully understand the positive role of indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

On the flip side, the limitations of indigenous knowledge may lead to adverse effects on wildlife. Bird-watching tourism should be an environmentally friendly industry without artificial interference in the natural conditions of wild birds. Birdwatchers should observe, appreciate, and record various characteristics and behavior of wild birds in their activities and habitats without affecting their normal life. However, Mangba bird-tourism operators are artificially feeding birds, which goes against the core concept of birdwatching. This is because artificial feeding damages the habitat of wild birds and affects their original living habits. However, villagers believe that such practices can increase the bird population as they comply with indigenous knowledge. This is due to the fact that indigenous knowledge is the embodiment of primitive biodiversity conservation, but lacks the support of modern ecological knowledge. Therefore, the lack of scientific guidance in indigenous knowledge damage the sustainability of the ecosystem to a certain extent. Therefore, bringing indigenous knowledge and modern science together to achieve the effective protection of biodiversity is a direction that needs the joint efforts of policy-making departments, wildlife-conservation agencies, and villagers. In essence, this is a topic that needs much research.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The case study presented here shows that under the influence of indigenous knowledge inherited from generation to generation, the Bulang people in Mangba developed a protective attitude toward banyan trees and the Derbyan Parakeet. Indigenous knowledge has also played an effective role in protecting forests, wild animals, and plants. At the same time, we have made an in-depth analysis of the impact of indigenous knowledge on forest and wildlife protection. In this study, we found that even without specific punishment measures, the local people effectively controlled the use of natural resources through moral constraints, public opinion constraints, and worship rituals. This protection system is based on the worship of primitive nature and the oral transmission of indigenous knowledge from generation to generation. The inheritance of indigenous knowledge reflects the relationship between local people and nature, it provides information necessary for survival and the protection of forest and wildlife resources in a specific environment.

By recording and discussing these indigenous knowledge, this study will help to arouse more extensive attention and discussion on indigenous knowledge in academic circles. The research results will help to ensure the diversity of forest resources and wildlife resources through villagers’ spontaneous protection in poor rural areas and areas not yet touched by modern scientific means. At the same time, this study also pays attention to the ecological welfare brought by indigenous knowledge to local people. In the development of birdwatching tourism, villagers have gained real economic benefits. This will further promote the positive ecological impact of these areas and will provide a shining example for many other poor groups in the world who are often in similar situations. However, through the example of bird watching tourism, it is also found that indigenous knowledge may indirectly lead to ecosystem imbalance in the absence of modern scientific guidance, which is worrying. Due to the limitations of the research object and the infancy of bird watching tourism, the research on the impact of this indigenous knowledge’s own defects is not enough, which is also the focus and follow-up direction of future research.

All in all, respecting cultural diversity, and maintaining and innovating indigenous knowledge are the key factors to be encouraged for long-term sustainable development and biodiversity protection in rural areas. Therefore, this study suggests that the participation of indigenous knowledge holders in policy formulation and implementation processes should be promoted and the power of traditional leaders as guardians of forest and wildlife resources in specific areas should be enhanced. Meanwhile, policy makers and development practitioners should also respect cultural diversity, take into account the role and impact of indigenous knowledge in rural areas, and provide more for local people’s space and autonomy. To prevent the marginalization of indigenous knowledge, we should undertake measures to publicize and disseminate it. Understanding and recognizing its value ensures its inheritance and continuation. At the same time, recording indigenous knowledge and its corresponding practices and technology can provide a basis for comparison for present and future generations. In addition, when protecting forests, wild animals, and plant resources, natural resource management departments and animal- and plant-protection institutes should be encouraged to cooperate with local people. In this context, the ecological knowledge of the local people should be improved through explanation and practice and the misunderstanding that local indigenous knowledge may have a negative impact on the ecosystem should be corrected. This may be effective in innovating indigenous knowledge and solving the problem of lack of scientific support for indigenous knowledge. In short, to effectively protect biodiversity by combining indigenous knowledge and modern science, more research is needed in the future.