Towards a Characterization of Working Forest Conservation Easements in Georgia, USA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

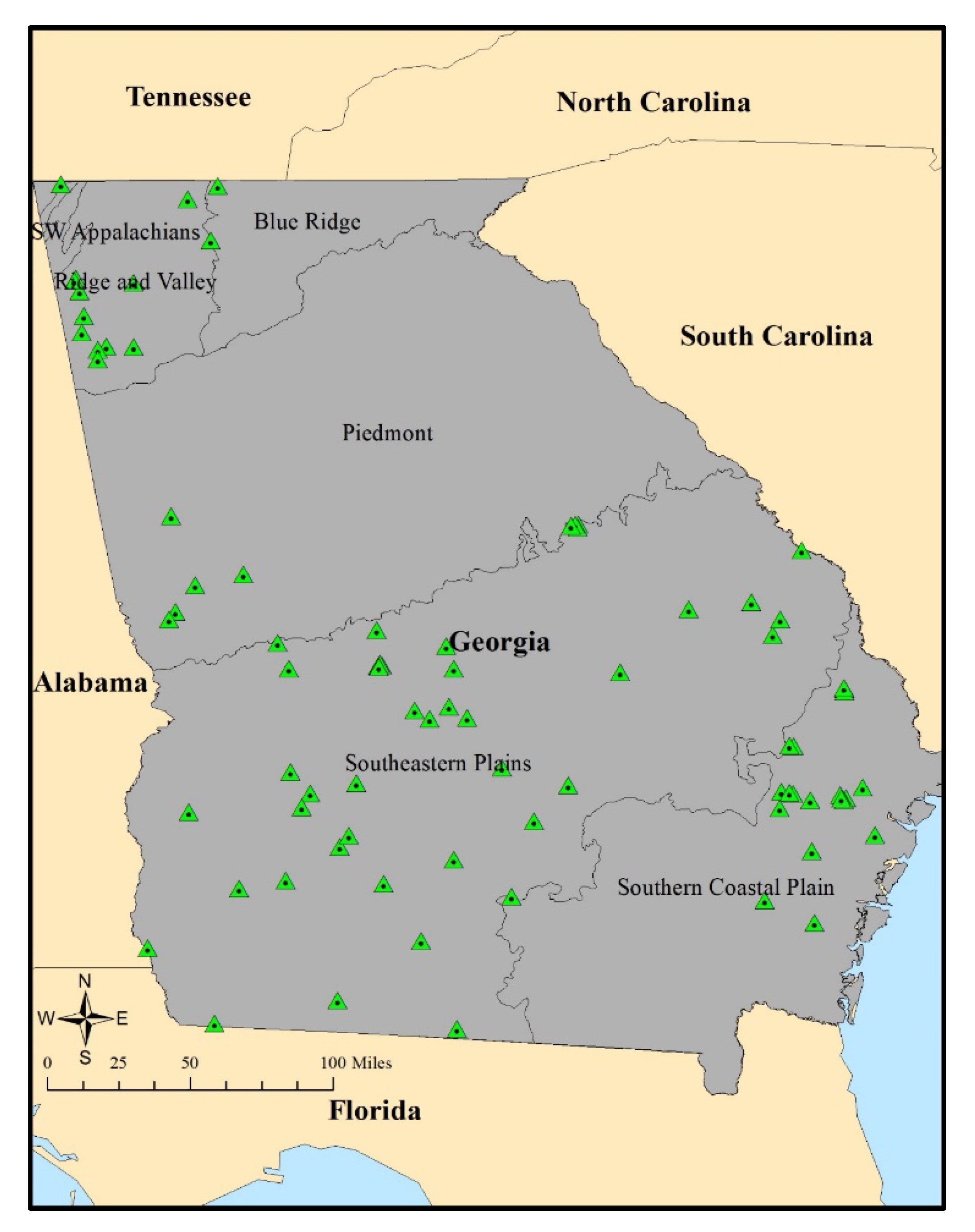

2.1. Data

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Easement Themes

2.2.2. Land Use Types

- Bottomland hardwood (BH) areas were classified as locations where soil is periodically inundated by water during several parts of the year. Common tree species included baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), several gum species (Nyssa spp.), and river birch (Betula nigra). These forests provide crucial ecosystem services such as greenhouse gas mitigation, reducing flood severity and risk, enhancing water quality, and reducing the amount of sediment entering waterways [33,34]. The extent of these forests has been significantly reduced from their historical occurrence across the southeastern USA, mainly due to conversion of these areas to cropland uses [35,36].

- Mesic/upland hardwoods (MH) were classified as areas with moist to xeric soil types dominated by many species of oak (Quercus spp.), hickory (Carya spp.), and beech (Fagus spp.) [37]. This forest type provides critical wildlife forage habitat, a diversity of forest products, and multiple forest management opportunities [38,39].

- Mixed pine/hardwood (MIX) land use consisted of an assemblage of mixed pine and hardwood stands. Within this forest type, select sites were characterized as primarily pine with some hardwood understory, or predominantly hardwoods with pines interspersed throughout the stand.

- Natural pine (NP) land use consisted of typically xeric, sandier sites with tree species consisting of nonplanted longleaf (Pinus palustris), slash (Pinus elliottii), or loblolly pine (Pinus taeda). Natural pine areas have decreased dramatically in the past three decades with 9.3 million acres of this forest type present in 1972 compared to around 4.1 million acres today [1,40].

- Planted pine (PP) areas were locations in which pine species had been either hand or machine planted. Typically, this forest type was where most forest management activity was present.

- Fields/pasture (FP) lands consisted of open areas that were used primarily for livestock grazing, abandoned agricultural fields, or power line right-of-ways.

- Wildlife food plots (WFP) were areas planted with native grasses or crops to be used primarily as forage areas for wildlife species. They were primarily used as a supplement to hunting activity on easement sites. These areas are typically small openings within or along forest stands.

- Evergreen hammocks (EH) were classified as small upland areas surrounded by wetlands or floodplains where fire is generally excluded. Common canopy species include submesic oaks, magnolia species (Magnolia spp.), and American holly (Ilex opaca). These areas are critical for conservation due to their threatened status from increasing fragmentation and conversion to agriculture or development.

- Lastly, bogs/limesinks (BL) consisted of depressional wetlands that often form in grassy savanna areas dominated by evergreen shrubs, sedges, and rushes. These areas are often critical habitat for many species of reptiles, amphibians, and plants that are adapted to these habitat conditions to survive [41,42].

2.2.3. Recreational Opportunities

2.2.4. Hydrologic Features

2.2.5. Forest Management

3. Results

3.1. Land Use Types

3.2. Recreational Activities

3.3. Hydrological Features

3.4. Forest Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GFC. Sustainability Report for Georgia’s Forests: January 2019; Georgia Forestry Commission: Macon, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Enterprise Innovation Institute. 2018 Economic Benefits of the Forest Industry in Georgia; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.; Williams, T.; Rodriguez, E.; Hepinstall-Cymmerman, J. Quantifying the Value of Non-Timber Ecosystem Services from Georgia’s Private Forests; Georgia Forestry Foundation: Forsyth, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wear, D.N.; Greis, J.G. The Southern Forest Futures Project: Summary Report; USDA-Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2012; pp. 1–54.

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, D.W.; Schelhas, J. Small-scale non-industrial private forest ownership in the United States: Rationale and implications for forest management. Silva Fenn. 2005, 39, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haines, A.L.; Kennedy, T.T.; McFarlane, D.L. Parcelization: Forest change agent in northern Wisconsin. J. For. 2011, 109, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Land Trust Alliance. Conservation Options. Available online: https://www.landtrustalliance.org/what-you-can-do/conserve-your-land/conservation-options (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Yin, G. A Comparative Analysis of Industrial Timberland Property Taxation in the US South; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, T.L.; Newman, D. Analysis of relative tax burden on nonindustrial private forest landowners in the southeastern United States. J. For. 2018, 116, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mei, B.; Izlar, R.L. Impact of forest-related conservation easements on contiguous and surrounding property values. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 93, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, M.; Zhang, D. Property tax policy and land-use change. Land Econ. 2008, 84, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, R.A. Conservation easements: Permanent shields against sprawl. J. For. 2002, 100, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Merenlender, A.M.; Huntsinger, L.; Guthey, G.; Fairfax, S.K. Land trusts and conservation easements: Who is conserving what for whom? Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamblee, J.F.; Colwell, P.F.; Dehring, C.A.; Depken, C.A. The effect of conservation activity on surrounding land prices. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheever, F.; McLaughlin, N.A. An introduction to conservation easements in the United States: A simple concept and a complicated mosaic of law. J. Law Prop. Soc. 2015, 1, 107–186. [Google Scholar]

- Owley, J. The enforceability of exacted conservation easements. Vt. Law Rev. 2011, 36, 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, P. Protecting the Future Forever: Why Perpetual Conservation Easements Outperform Term Easements; Land Use Clinic Paper 10; University of Georgia School of Law: Athens, GA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K. National Land Trust Census Report: Our Common Ground and Collective Impact; Land Trust Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Conservation Easement Database. Easement Holder Profile. Available online: https://www.conservationeasement.us/eholderprofile/ (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Yoo, J.; Ready, R. The impact of agricultural conservation easement on nearby house prices: Incorporating spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity. J. For. Econ. 2016, 25, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, J. Value capitalization effect of protected properties: A comparison of conservation easement with mixed-bag open spaces. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2014, 6, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan, J.; Lynch, L.; Bucholtz, S. Capitalization of open spaces into housing values and the residential property tax revenue impacts of agricultural easement programs. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2003, 32, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polasky, S.; Nelson, E.; Lonsdorf, E.; Fackler, P.; Starfield, A. Conserving species in a working landscape: Land use with biological and economic objectives. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rissman, A.R.; Lozier, L.; Comendant, T.; Kareiva, P.; Kiesecker, J.M.; Shaw, M.R.; Merenlender, A.M. Conservation easements: Biodiversity protection and private use. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.R.; Meretsky, V.; Knapp, D.; Chancellor, C.; Fischer, B.C. Why agree to a conservation easement? Understanding the decision of conservation easement granting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Aguilar, F.X.; Butler, B.J. Conservation easements and management by family forest owners: A propensity score matching approach with multi-imputations of survey data. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, M.J.; Richardson, J.J.; Huff, J.S.; Haney, H.L. A survey of forestland conservation easements in the United States: Implications for forestland owners and managers. Small-Scale For. 2007, 6, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgia State Properties Commission. Building Land & Lease Inventory of Property. Available online: https://www.realpropertiesgeorgia.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- GSCCCA. The Clerks Authority. Available online: https://www.gsccca.org/search (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- TMS. Quarterly Market Bulletin: 3rd Quarter 2019; TimberMart-South: Athens, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silge, J.; Robinson, D. Tidytext: Text Mining and Analysis Using Tidy Data Principles in R. J. Open Source Softw. 2016, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Georgia State Wildlife Action Plan; Department of Natural Resources: Social Circle, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Capon, S.; Chambers, L.; Mac Nally, R.; Naiman, R.; Davies, P.; Marshall, N.; Pittock, J.; Reid, M.; Capon, T.; Douglas, M.; et al. Riparian ecosystems in the 21st century: Hotspots for climate change adaptation? Ecosystems 2013, 16, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W.A.; Murray, B.C.; Kramer, R.A.; Faulkner, S.P. Valuing ecosystem services from wetlands restoration in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Bottomland Hardwoods. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/bottomland-hardwoods (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- King, S.L.; Keim, R.F. Hydrologic modifications challenge bottomland hardwoodforest management. J. For. 2019, 117, 504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, C.J. History, highlights, and perspectives of southern upland hardwood silviculture research. J. For. 2019, 117, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabo, D.; Peairs, S.; Dickens, D. Managing Upland Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest Types for Georgia Landowners; Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources: Athens, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger, A.J.; Moorman, C.E.; Lashley, M.A.; Chitwood, M.C.; Harper, C.A.; DePerno, C.S. White-tailed deer use of overstory hardwoods in longleaf pine woodlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 464, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandeis, T.J.; McCollum, J.M.; Hartsell, A.J.; Brandeis, C.; Rose, A.K.; Oswalt, S.N.; Vogt, J.; Marcano Vega, H. Georgia’s Forests; U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Species Fact Sheets. Available online: https://georgiawildlife.com/species (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Palik, B.J.; Golladay, S.W.; Taylor, B.W. Invertebrate communities of forested limesink wetlands in southwest Georgia, USA: Habitat use and influence of extended inundation. Wetlands 1997, 17, 383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kreye, M.M.; Adams, D.C.; Escobedo, F.J. The value of forest conservation for water quality protection. Forests 2014, 5, 862–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiesecker, J.M.; Comendant, T.; Grandmason, T.; Gray, E.; Hall, C.; Hilsenbeck, P.; Kareiva, P. Conservation easements in context: A quantitative analysis of their use by The Nature Conservancy. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesini, D. Working forest conservation easements. Urban Lawyer 2009, 41, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- GFC. Georgia’s Best Management Practices for Forestry; Georgia Forestry Commission: Macon, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, P.; Noss, R.F. Do habitat corridors provide connectivity? Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskowiak, D.; Stoll, L. Planning Implementation Tools: Conservation Easements; Center for Land Use Education, University of Wisconsin Stevens Point: Wasau, WI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braza, M. Effectiveness of conservation easements in agricultural regions. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, J.O. Using conservation easements to protect open space: Public policy, tax effects, and challenges. J. Prop. Tax Assess. Adm. 2013, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, J.R.; Brenner, J.C.; Drescher, M.; Dickinson, S.L.; Knackmuhs, E.G. Perpetual private land conservation: The case for outdoor recreation and functional leisure. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farmer, J.R.; Chancellor, C.; Brenner, J.; Whitacre, J.; Knackmuhs, E.G. To ease or not to ease: Interest in conservation easements among landowners in Brown County, Indiana. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.R.; Ma, Z.; Drescher, M.; Knackmuhs, E.G.; Dickinson, S.L. Private landowners, voluntary conservation programs, and implementation of conservation friendly land management practices. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissman, A.R. Rethinking property rights: Comparative analysis of conservation easements for wildlife conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pocewicz, A.; Kiesecker, J.M.; Jones, G.P.; Copeland, H.E.; Daline, J.; Mealor, B.A. Effectiveness of conservation easements for reducing development and maintaining biodiversity in sagebrush ecosystems. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.; Wigley, T.B.; Miller, K.V. Managed forests and conservation of terrestrial biodiversity in the southern United States. J. For. 2009, 107, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Carnus, J.M.; Parrotta, J.; Brockerhoff, E.; Arbez, M.; Jactel, H.; Kremer, A.; Lamb, D.; O’Hara, K.; Walters, B. Planted forests and biodiversity. J. For. 2006, 104, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.J.; Chamberlain, M.J. Efficacy of herbicides and fire to improve vegetative conditions for northern bobwhites in mature pine forests. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2004, 32, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.E.; Iglay, R.B.; Evans, K.O.; Wigley, T.B.; Miller, D.A. Estimating capacity of managed pine forests in the southeastern U.S. to provide open pine woodland condition and gopher tortoise habitat. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.A.; Wigley, T.B. Introduction: Herbicides and forest biodiversity. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2004, 32, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Margules, C.R.; Botkin, D.B. Indicators of biodiversity for ecologically sustainable forest management. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, P.; Boston, K.; Siry, J.P.; Grebner, D.L. Forest Management and Planning, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; p. 331. [Google Scholar]

| Size Category | Count | Total Acres | Average | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <500 | 35 | 9046.50 | 258.47 | 59.00 | 460.00 | 126.70 |

| 500–1000 | 22 | 15,976.00 | 726.18 | 506.00 | 987.00 | 169.91 |

| >1000 | 29 | 74,217.00 | 2559.21 | 1009.00 | 5285.00 | 1409.03 |

| Grand Total | 86 | 99,239.50 | 1153.95 | 59.00 | 5285.00 | 1311.05 |

| WFP % | BH % | PP % | MIX % | FP % | MH % | NP % | BL % | EH % | Theme Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Habitat | 93.59 | 93.42 | 92.75 | 95.38 | 100.00 | 96.30 | 95.35 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 81 |

| Conservation Values | 91.03 | 89.47 | 91.30 | 89.23 | 90.74 | 90.74 | 90.70 | 92.31 | 92.86 | 78 |

| Hydrologic Habitat | 88.46 | 100.00 | 89.86 | 89.23 | 85.19 | 87.04 | 86.05 | 92.31 | 100.00 | 76 |

| Endangered or Threatened Species | 29.49 | 34.21 | 28.99 | 40.00 | 35.19 | 25.93 | 30.23 | 30.77 | 28.57 | 75 |

| Enhance Scenic Quality | 50.00 | 51.32 | 50.72 | 55.38 | 53.70 | 51.85 | 41.86 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 45 |

| Soil Productivity | 88.46 | 88.16 | 86.96 | 84.62 | 94.44 | 85.19 | 83.72 | 84.62 | 85.71 | 38 |

| GCWCS | 28.21 | 31.58 | 24.64 | 32.31 | 22.22 | 29.63 | 32.56 | 26.92 | 21.43 | 29 |

| Protect Historic Features | 33.33 | 34.21 | 36.23 | 32.31 | 42.59 | 37.04 | 30.23 | 50.00 | 57.14 | 24 |

| Enhance Connectivity | 19.23 | 19.74 | 17.39 | 21.54 | 20.37 | 22.22 | 23.26 | 30.77 | 35.71 | 16 |

| Public Access | 3.85 | 3.95 | 4.35 | 4.62 | 0.00 | 3.70 | 6.98 | 3.85 | 0.00 | 3 |

| Land Use Type Total | 78 | 76 | 69 | 65 | 54 | 54 | 43 | 26 | 14 | - |

| Recreation | Pond | Lake | Creek/Stream | River | Activity Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunting | 100.00% | 100.00% | 98.80% | 100.00% | 85 |

| Fishing | 100.00% | 100.00% | 98.80% | 100.00% | 85 |

| Camping | 100.00% | 100.00% | 98.80% | 100.00% | 85 |

| Hiking | 100.00% | 100.00% | 97.59% | 100.00% | 84 |

| All-Terrain Vehicle | 93.88% | 100.00% | 91.57% | 82.35% | 79 |

| Horseback Riding | 91.84% | 90.91% | 89.16% | 76.47% | 77 |

| Watersports | 65.31% | 54.55% | 50.60% | 70.59% | 43 |

| Feature Total | 49 | 11 | 83 | 17 | - |

| Forest Management Plan | Number | % | Activity | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | 83 | 96.51 | Clearcut | 79 | 91.86 |

| Registered Forester/Biologist | 82 | 95.35 | Selective Harvesting | 84 | 97.67 |

| 5-Year Plan | 5 | 5.81 | Prescribed Burning | 82 | 95.35 |

| 10-Year Plan | 7 | 8.14 | Thinning | 84 | 97.67 |

| 15-Year Plan | 36 | 41.86 | Herbicide/Fertilizer | 78 | 90.70 |

| Unlisted | 38 | 44.19 | Exotic/Invasive removal | 85 | 98.84 |

| Restriction | <500 | 500–1000 | >1000 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Natural Area | 28 | 20 | 27 | 75 |

| Special Natural Area (Average %) | 19.54% | 31.20% | 20.88% | 26.30% |

| Forestry Only Area | 15 | 7 | 12 | 34 |

| Clearcut Size Restriction | 9 | 8 | 8 | 25 |

| Clearcut Prohibition | 5 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Residual Basal Area | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Grade 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 13 |

| Grade 2 | 16 | 11 | 14 | 41 |

| Grade 3 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 22 |

| Grade 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Grade 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 35 | 22 | 29 | 86 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reeves, T.; Mei, B.; Siry, J.; Bettinger, P.; Ferreira, S. Towards a Characterization of Working Forest Conservation Easements in Georgia, USA. Forests 2020, 11, 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060635

Reeves T, Mei B, Siry J, Bettinger P, Ferreira S. Towards a Characterization of Working Forest Conservation Easements in Georgia, USA. Forests. 2020; 11(6):635. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060635

Chicago/Turabian StyleReeves, Tyler, Bin Mei, Jacek Siry, Pete Bettinger, and Susana Ferreira. 2020. "Towards a Characterization of Working Forest Conservation Easements in Georgia, USA" Forests 11, no. 6: 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060635

APA StyleReeves, T., Mei, B., Siry, J., Bettinger, P., & Ferreira, S. (2020). Towards a Characterization of Working Forest Conservation Easements in Georgia, USA. Forests, 11(6), 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060635