Abstract

Copal is a resin of ritual uses in Mexico that is extracted from several species of trees of the genus Bursera. The effect of traditional management on phenotypical traits of copal trees has not been sufficiently studied. This research analyzed the traditional management and human selection on populations of Bursera bipinnata, and it also examined their influence on the quantity and quality of the resin produced by wild and managed trees. The management of copal was documented through semi-structured interviews and workshops. Samples of 60 trees from six wild and managed populations were selected to quantify the production of resin during two consecutive years. Fresh resin was collected to identify organic volatile compounds through gas chromatography and Principal Components Analysis (PCA); individuals were classified according to the amount and type of organic compounds produced. We identified management strategies from simple harvesting to seeds planting. The criteria of local people for selecting managed trees and seeds are based on the quantity and quality of the resin produced per tree, which were significantly higher in managed than in wild trees: 190.17 ± 329.04 g vs. 29.55 ± 25.50 g (p = 0.003), and 175.88 ± 179.29 g vs. 63.05 ± 53.25 g (p = 0.008) for the production seasons of 2017 and 2018, respectively. Twenty organic volatile compounds were identified, and the PCA showed that managed trees produce higher percentages of compounds associated with scent. The traditional management of Bursera bipinnata involves selective pressures, which generate the differentiation of wild and managed trees that may represent incipient domestication through silvicultural management.

1. Introduction

Mesoamerica is the cultural region comprised from southern Mexico to northern Costa Rica [1], which has contributed to humanity through important crops, plant management strategies, and plant diversification through domestication [2,3,4]. The agricultural and silvicultural management of plant populations have promoted morphological, physiological, genetic, and phytochemical diversification in features of human interest [5,6,7,8,9,10], compared with unmanaged or incipiently managed populations [11]. Silvicultural management, also referred to as in situ management, can include the collection, tolerance, promotion, and protection of some individuals with desirable attributes in wild vegetation, agroforestry systems, fallow areas, and other anthropized zones [4,5,8,11,12,13]. Silvicultural management is characterized by deliberately leaving standing individuals that have good phenotypes for humans [3,4,11], and their management seeks to increase the numbers of individuals or populations with attributes desired by humans in wild or managed areas [4]. Such management commonly increases the frequency of good phenotypes (with desirable morphological and physiological features) in the managed areas [5,12,13,14].

Different studies have documented examples of how silvicultural management operates and may involve domestication processes [8,11,15,16,17], but most of them have focused on edible species. Research on the management of medicinal, ornamental, and ritual species is still limited, even though these use categories often appear the most in ethnobotanical reports in Mexico [13,18,19].

Among the examples of non-edible managed plant species, the copal trees are highly important. Copal is an aromatic resin extracted from different tree species of the Burseraceae family [20], which has a Pantropical distribution [21]. Several genera and species produce resin of different types and qualities, and specialized techniques are used for its extraction [22,23]. In Mexico, around 30 tree species are used for extracting copal since pre-Hispanic times for ritual and medicinal purposes [24]. Bursera copallifera (Moc &. Sessé ex DC.) Bullock and Bursera bipinnata (Moc. & Sessé ex DC.) Engl. are the most widely used species [25]. Currently, the ritual use is the most common, given its use in many religious ceremonies, especially for the Day of the Dead [26], which is one of the most important festivals in Mexico, especially in the rural areas [27]. Copal resin is a non-timber forest product (NTFP) with high economic value and of high cultural importance [21,26]. It is estimated that one-third of the copal production consumed in Mexico is produced in the Upper Balsas River basin, particularly in the southeast of the state of Morelos and the neighboring southwest of the state of Puebla, in the Mixteca Poblana region, which is an area with a semiarid climate dominated by a tropical deciduous forest [25]. This region is an important reservoir of species richness, knowledge, and management techniques for copal trees.

The use of copal resin has been widely documented, in particular for rituals and medicinal uses, past and present uses, species used, extraction processes, and local nomenclature [24,27]. However, traditional management practices and strategies have not been sufficiently studied. Technical descriptions about resin extraction are available [25,26], but these do not explain the management of trees, collectors’ motivations to manage them, the occurrence of selective processes and selection criteria, nor the consequences of management practices on resin yield and quality. Clarifying these questions would allow assessing the contributions of traditional management of B. bipinnata to the sustainability of copal resin extraction. In turn, it would provide information on experiences that allow conservation of the biological diversity of the tropical deciduous forest and the livelihood of people who are dedicated to this activity.

Cruz et al. [26] and Mena [28] documented that in South Central Mexico, copal collectors identify intraspecific variation of trees; among them, there are some with morphological attributes that produce large quantities of resin of strong scent, which are considered of higher quality than others. These trees are generally tolerated and promoted in crop fields as live fences or as vegetation islands [26]. Collectors also distinguish other trees named by them as copal cimarrón or copal de monte (wild trees), which are abundant in the wild and produce less resin of lower quality than managed trees [26,28].

This study aimed to document the traditional management and selection criteria for favoring good phenotypes of copal B. bipinnata in managed areas. In addition, we analyze the effects of management and selection on the abundance of trees with preferred attributes (higher yield and quality of the resin), compared with those existing in wild populations. We hypothesized that given the economic and cultural importance of copal in the region studied, the silvicultural in situ management strategies would be diverse and would include selective processes directed to increase the dominance of individuals with desired attributes (higher yield and quality of the resin) in managed populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

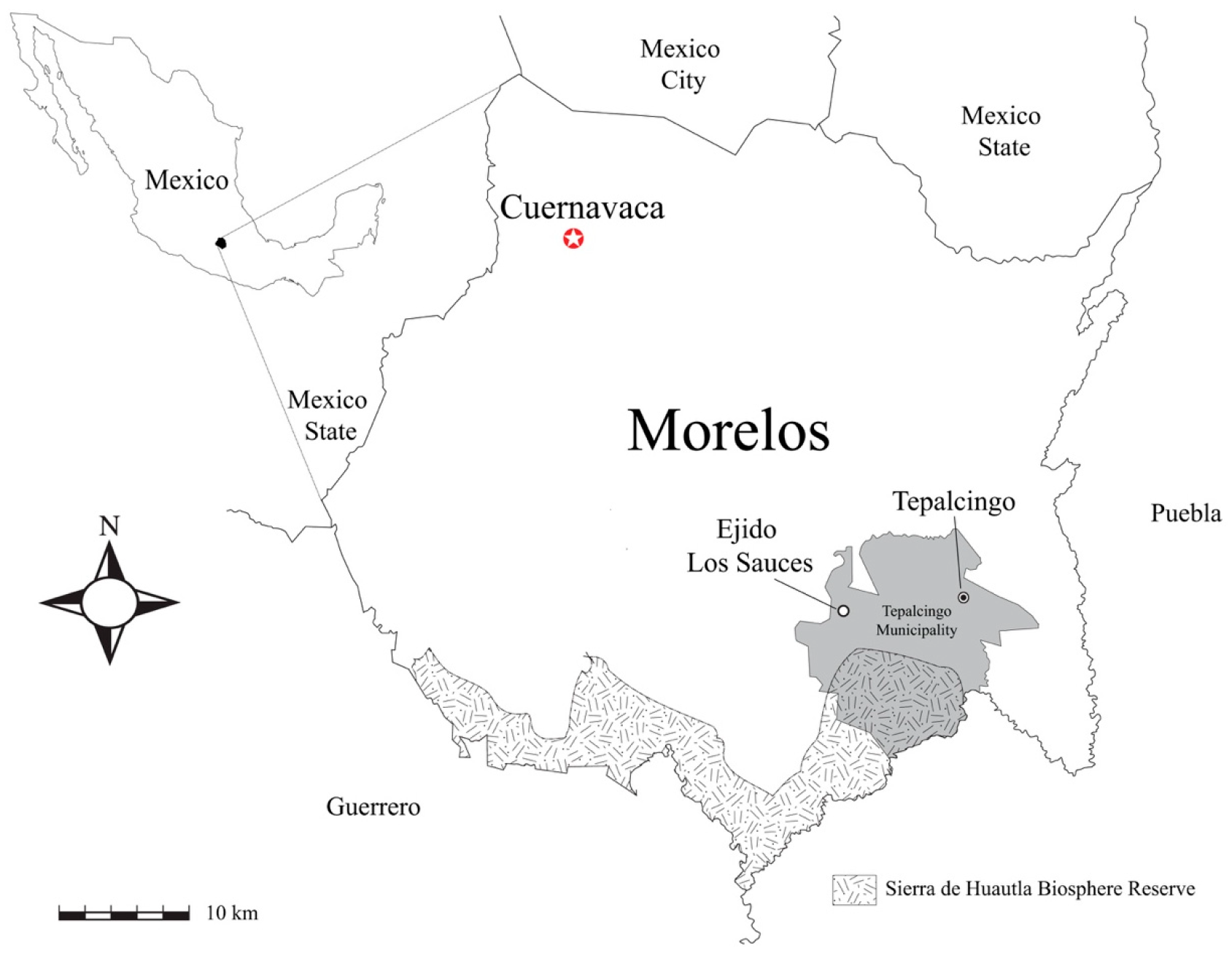

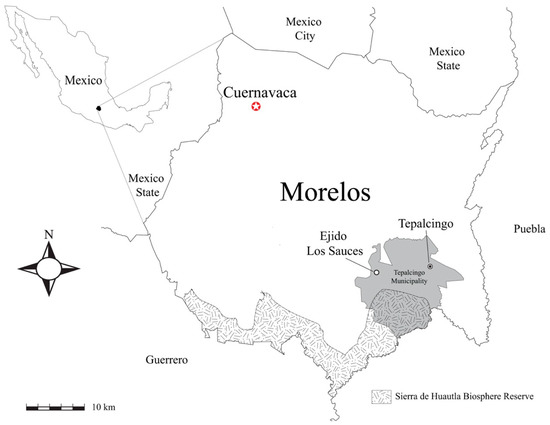

The study was carried out in Los Sauces, a rural community of the Municipality of Tepalcingo, in the SE of the State of Morelos, South Central Mexico within the upper Balsas River basin (Figure 1). The community is located at the margins of the Sierra Huautla Biosphere Reserve (REBIOSH for its acronym in Spanish), at an elevation of 1281 m, with a sub-humid climate [29]; it has an area of 2262 ha [30] dominated by Tropical Deciduous Forest (TDF) [31]. TDF is characterized by the presence of small trees (4 to 10 m high, eventually up to 15 m) and abundant vines. In addition, most species lose their leaves for periods of five to seven months. A large number of the species produce exudates (resin or latex), and their leaves have fragrant odors when squeezed. The herbaceous stratum can only be appreciated in the rainy season. Some of the characteristic species of TDF are Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl., Ceiba aesculifolia subsp. parvifolia (Rose) P.E.Gibbs & Semir, Conzattia multiflora (B.L. Rob.) Standl., Ficus petiolaris Kunth, Guazuma ulmifolia Lam., Lysiloma divaricata (Jacq.) J.F.Macbr., and Sapindus saponaria L. Among the species of the genus Bursera are Bursera aptera Ramírez, Bursera bicolor (Willd. ex Schltdl.) Engl., B. bipinnata, B. copallifera, Bursera fagaroides (Kunth) Engl., Bursera glabrifolia (Kunth) Engl., Bursera lancifolia (Schltdl.) Engl., Bursera linanoe (La Llave) Rzed., Calderón & Medina, and Bursera morelensis Ramírez can be found. In the community studied, copal resin is only extracted from B. bipinnata and B. copallifera [32]. The resin of B. bipinnata is more appreciated due to its better quality and because it is sold at a higher price.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area, emphasizing the area corresponding to the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve.

Los Sauces has a population of live 298 inhabitants, whose main productive activities are the agriculture of maize, squashes, and beans, and some small-scale commercial crops such as sorghum, watermelon, melon, and jicama are also produced [33]. Copal extraction has been widely carried out in the region for more than 100 years [26], and currently, it is widely practiced as a key seasonal income that provides to people livelihood for the rest of the year.

2.2. Documenting Management Strategies

Copal trees are tapped (“picado de copal”) by making parallel gashes in the branches (occasionally also in the trunk with a machete). This activity is strongly associated with gender since only men do it, fathers being responsible for transmitting to their sons knowledge about the extraction and care techniques of copal trees. We documented copal management through 30 semi-structured interviews and participatory workshops [34,35] with copaleros (people dedicated to extract copal). The interviews allowed us to explore what copal varieties are identified by copaleros, as well as their selection criteria, knowledge, management practices, organization, and associated cultural aspects. The average age of the copaleros interviewed was 47 ± 16 years. They reported on average 22 ± 19 years of experience extracting copal. Besides working on copal extraction, they also work on agriculture and cattle herding activities. At the same time, a workshop was performed with the participation of 30 copal managers, including some personally interviewed. The workshop focused on documenting the classification and selection criteria, the management practices, and the distribution of copal trees in the communal territory.

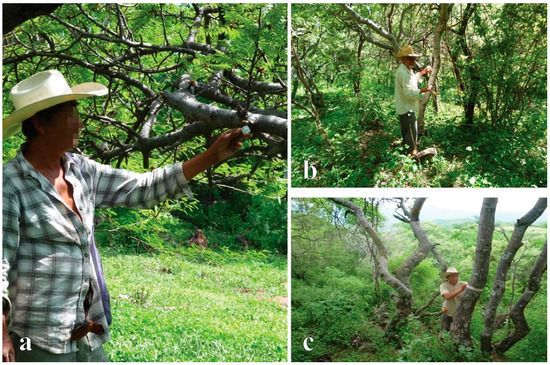

2.3. Quantification of Resin Yield in Wild and Managed Trees

Six sampling units (SU) 50 × 20 m2 were selected, three in wild populations and three in managed populations. Ten trees were sampled in each SU: 60 trees in total (30 trees from wild populations and 30 from managed SUs). Wild populations were defined as those found in natural vegetation that has not been opened to agriculture, and whose trees have not been used for extracting copal or tapped. Managed populations were those sites where copal trees have been selected for their attributes and dispersed intentionally on the margins and inside plots of crop fields (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Selection and marking of trees in managed and wild parcels: (a) Managed trees; (b) and (c) Wild trees.

For each sampling unit, we randomly selected B. bipinnata trees, recording their diameter at breast height (DBH) between 10 and 20 cm (these are the trees typically tapped), and their height (m), canopy cover (m2), and DBH (cm) were recorded as well. To evaluate possible significant differences between these variables in relation to their wild and managed condition, a t-student test was performed using R [36]. Following traditional tapping techniques [26], for each tree, an incision was performed and resin was collected; a new incision was made again only when the previous one ended to dripping resin. This routine was repeated as many times as needed during the three-month period of copal tapping season (from August to October), and it was repeated for two consecutive years (Figure 3). The studied trees were monitored every three days, collecting resin and changing the collection receptacles following the traditional way of obtaining copal [28]. Only the resin collected in Agave leaves (“copal en penca” or “planchita”) was considered in our quantification of resin yield. This was because this resin is what copaleros sell and where they dedicate their greatest collecting efforts. The other types of resin, such as teardrop (lágrima), myrrh, and gum (goma), were not considered in this study. The total amount of resin produced weekly per tree was weighed on a digital scale (Tanita Professional Mini) to obtain the average amount of resin produced in the three SUs per population type (wild and managed) during two production seasons.

Figure 3.

Tapping technique in B. bipinnata trees.

To test the significance of differences in resin production between wild and managed populations and to rule out the potential influence of environmental variables in each site, a covariance analysis was performed for each collection season, with the average temperature and relative humidity as covariables. For measuring the covariables, six environmental monitoring micro-stations were installed, one in each wild and managed population. The stations were programmed to record weekly measurements (10 measurements per condition) during the two tapping seasons. The data were analyzed using the R statistical program [36].

2.4. Identification of Organic Compounds in Copal Resin from Wild and Managed Trees

To compare the resin chemical profile from wild (N = 24) and managed trees (N = 24), a small sample of fresh resin was collected (≈0.280 g). This resin was immediately stored in an amber vial, with 3 mL of reactive grade hexane (Baker). The samples were transported in ice and kept refrigerated at −10 °C until the analysis [37].

From each sample, an aliquot was mixed in a vortex with 500 µL of a tetradecane solution (0.5 mg mL−1). The mix was concentrated to a volume of 250 µL with gaseous nitrogen. Afterwards, 20 µL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) were added and heated at 30 °C for 10 min [38].

From each sample, 2 µL were analyzed with an Agilent 6890 Gas Chromatography equipment with an HP-5MS (5% Phenyl 95% dimethylpolysiloxane) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm with 0.25 mm film thickness), which was coupled to an Agilent 5973N selective mass detector. Helium was used as a carrier gas at 7.67 psi with a 1.0 mL min−1 constant flow. The front inlet was maintained at 280 °C in a split ratio of 20:1. The initial oven temperature was set at 50 °C for 5 min and increased to 200 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1, and to 290 °C at a rate of 25 °C min−1 for 13 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in electrical ionization mode (EI), with a flow of 1 mL min−1, 70 eV ionization voltage, the interface temperature at 300 °C, and a scan range of 40–500 m/z [39]. The compounds were identified by comparing the mass spectra of each constituent with those stored in the NIST2011.L database and with mass spectra from the literature [40,41]. The Retention Index (RI) values were compared to those reported in the literature [37,40,42,43]. The concentration of volatile and semi-volatile compounds was calculated based on an internal standard that consisted of a tetradecane solution (0.25 mg mL−1) [43,44]. Due to a lack of uniformity in the weight of the hexane-dissolved samples, percentages of the compounds of the samples were used. We used a limit of detection (LOD) criteria, only including peaks with a signal to noise (S/N) ratio equal or higher than 2. Therefore, missing data (7%) were imputed using the Random Forest Algorithm for each wild and managed population. Afterwards, concentration values were transformed using the Box–Cox method [45].

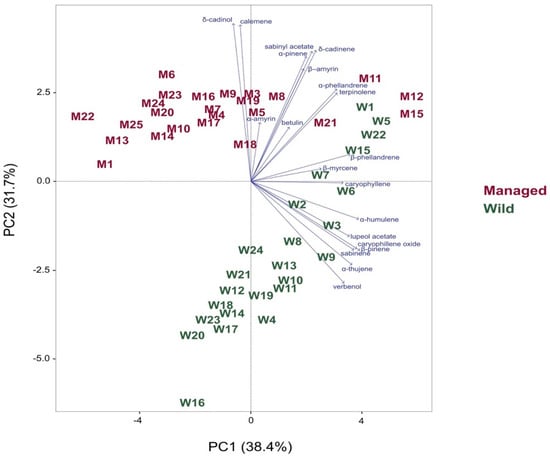

A Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was performed to explore the different concentration patterns of the organic compounds between wild and managed tree populations [36].

3. Results

3.1. Local Criteria for Classifying Copal Trees

People that manage copal trees recognize, name, and classify copal trees based on different criteria. First, they classify them according to their morphological attributes, for which they recognize four species: chino (B. bipinnata), ancho (B. copallifera), ticumaca (B. bicolor), and linaloe (B. linanoe). From the three locally recognized copal species, only the first two are tapped. Copal chino is the most valued, mainly for its high resin yield, scent, and consistency, followed by copal ancho. A second criterion is based on the origin of trees: there can be “field copal” (copal de las parcelas), and “wild” or “forest copal” (copal cimarrón or de monte); the latter are not used for resin extraction because there is a perception that these trees produce very low amount of resin. A third criterion is the consistency of the resin, which is classified in two types: “aguada” (liquid) and “sólida” (solid). This classification criterion is applied to B. bipinnata as well as B. copallifera, and in general, there is a higher occurrence of liquid copal resin in trees from the forest or wild (Table 1). A fourth criterion is scent, people recognizing two scents, the “normal” copal (of soft scent), and lemon-scented copal (of intense and fragrant scent), which is highly valued although it is scarce. A fifth criterion is color, and there can be three of them: white, yellow, and greenish blue. One last criterion is the form of the resin, which can be in penca (which has the bar form given by the agave leaf or penca, and is the most valued because of its economic and cultural value), lágrima (tear), goma (gum), mirra (myrrh), or cáscara (bark) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Criteria for the recognition and classification of copal.

Table 2.

Classification criteria and description of copal resin.

3.2. Management Strategies and Practices

Management practices for B. bipinnata involve a wide range of decisions, from the collective to the family and individual levels. Los Sauces is an ejido, a communal land tenure regime that emerged from the post-1910-17 revolution agrarian reform. Noteworthy, the constitutional amendments of 1992 enabled the formal recognition of individual tenure of parcels. Information from Los Sauces suggests that these changes resulted in complex formal and informal institutional arrangements where often individual decisions are taken at the plot level, but still, communal agreements are taken at the ejido level, including commercial forest management planning. Forest management plans (and equivalent instruments for commercial NTFP harvest), which include the authorized annual copal extraction quotas, are approved by the ejido’s assembly and sanctioned and verified by the Ministry of Environment (SEMARNAT). In the past, parcels, spots, or trees were designated individually for management. The person who was interested in extracting copal would ask for permission from the community’s general assembly. With the constitutional changes of 1992, each ejidatario (member of an ejido) is considered the owner of the trees in his/her plots; thus, owners do not need to ask for permission to use copal trees found in their parcels. However, it frequently happens that if the owner of a parcel does not have enough copal trees, he may ask owners of other parcels to let him tap trees in their parcels, so as to extract a higher quantity of resin. Copal managers who have a low density of trees in their parcels must work more, because they must transplant or plant trees in their parcels and wait at least eight years to extract from those trees.

Decisions at the family level can involve the rotation of extraction areas annually or biannually for those cases where copal managers have various parcels from which to tap resin. In contrast, if they have one or a few parcels, they may choose to let individual trees rest untapped for the season. In some cases when tapping activities cannot be conducted by a family member, arrangements with other skilled copaleros are sometimes made. The copalero is paid with half of the value of the copal sales from that parcel. Decisions at the individual level imply the use of specific tools and implements to extract resin, as well as the transmission of knowledge and extraction techniques to their children.

Both in situ and ex situ copal management practices were documented. In situ practices are performed within wild vegetation as well as inside croplands (agroforestry management). These practices include the following: (a) Collection (harvesting from trees found in wild vegetation, including resin naturally exuded, and those obtained through tapping); (b) tolerance (croplands are cleared before the sowing season, copal trees are left standing on their margins); (c) transplant (moving small trees to the margins of croplands, to prevent them from being damaged or eliminated during agricultural activities); (d) promotion (seedlings and trees are taken to pasturelands or other wild vegetation sites with low copal tree densities); and (e) protection (activities directed to accelerate plant growth, including eliminating surrounding plants, opening up space in the canopy, and getting rid of epiphytes). The purpose of all these practices are to increase the density of trees with favorable attributes in managed areas, to prevent erosion, establish resting sites and shade for cattle, limit parcels, and protect seedlings and young copal individuals.

Ex situ practices include the transplanting of vegetative parts—preferably through stakes,--planting complete individuals, and seeds sowing (Figure 4). The aim is to achieve the greatest tree survival rate and thus have material stock for the long run to reforest degraded areas with low copal densities (Figure 5; Table 3).

Figure 4.

Types of ex situ management, which include: (a) transplant of vegetative parts (stakes) and (b) planting of seeds.

Figure 5.

Arrangement of B. bipinnata trees in different management systems: (a) as part of wild vegetation, keeping connectivity with clearings within agricultural areas; (b) arranged at the margins of milpas (mixed maize, squash, and bean crops) and other crops as live fences or limits; and (c) as isolated elements that are tolerated in crop parcels.

Table 3.

Strategies and management practices for Bursera bipinnata copal trees.

Copaleros have several criteria to select the trees that will be tapped (Table 4): (a) appearance, that is, sturdy and healthy looking with no visible plagues or diseases; (b) size, trees with a diameter less than 10 cm are not tapped, as they produce little resin and tapping them may affect their ability to produce resin in the future or make them vulnerable to death; (c) age, trees are selected after 8 to 10 years old; (d) color and consistency of the bark, that is, the bark must be soft and shiny gray. Gray bark is associated to managed trees with higher resin production compared to wild trees that have a blackish bark, and which produce little resin and are hard to cut; (e) scent, in order to characterize this attribute, copal resin managers crush some leaves in their hand to perceive scent, and in this way, they decide whether to tap a tree or not; those with the strongest scents are considered trees of higher resin quality, and they are even selected to produce stakes and their seeds are collected to disseminate through community greenhouses; and (f) quantity of resin yielded is one of the definite selection criteria. A first sign of good production potential is that a tree exudes resin spontaneously. To further diagnose a tree’s potential, copal managers will probe the tree, making incisions in specific parts of the branches. If after three days no resin is exuded, it means that the tree is not apt for tapping and could eventually be eliminated if the parcel is used for agriculture. In contrast, if large quantities of resin are produced (1 kg per season), it will be considered an ideal tree to work the following years. Therefore, this will call for different management strategies, and therefore, diverse management techniques are practiced (Table 3).

Table 4.

Criteria for the selection of Bursera bipinnata trees for resin extraction.

3.3. Cultural Aspects of Copal Extraction

The ritual use of copal resin is linked to syncretic rites such as the blessing of seeds, the request for rain, and gratitude for the crops. For various religious celebrations, copal resin is sold in markets and is an omnipresent element in church altars, but especially in the offerings of homes, both in rural areas and in the city. In addition, the use of copal resin is associated with various ceremonies and rituals, for example, in divination and healing rituals, many of these of pre-Hispanic heritage. Some copaleros consider it important to ask the trees for permission to be tapped. Prayers are also commonly practiced before tapping trees, so as to protect themselves from the risks implied in the tapping activity, for instance bites and stings from animals (e.g., snakes, scorpions and wasps), from falling from the trees while tapping them, and to have a good harvest. Some of them take their tools to be blessed, tools such as the “quichala” or “quixala” (a type of sharp chisel, which is struck with a wooden hammer to make incisions in the bark), sledgehammer, and machete (Figure 6). In addition, at the end of the tapping season, copaleros give thanks for the harvest, taking candles and flowers to church. The cultural factor is a strong incentive for conservation of the copal trees and consequently, of their forests, to maintain and continue with their traditions and so that their children may continue extracting copal (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Quixala and hammers, traditional tools for tapping of B. bipinnata copal trees.

Figure 7.

Cultural maintenance mechanisms of the extraction of B. bipinnata copal resin activity: (a) Integration of the entire family in the cleaning of copal leaves (pencas); (b) altar for the Day of the Dead, which is set up inside houses from October 28th to November 2nd. Copal is an essential element.

3.4. Structural Variables and Copal Resin Production in Wild and Managed Populations

In terms of dasometric variables, managed trees were found to be taller, with greater cover and trunk diameter (DBH), compared with wild trees. These differences were statistically significant (Table 5). DBH is strongly correlated to the height and canopy cover of the trees, making it a functional category to compare resin production differences between wild and managed populations. The diameter categories chosen due to their presence in both wild and managed trees were 10 and 20 cm diameter. Our study showed that managed trees produced on average a greater quantity of resin (190.17 ± 329.04 g in the 2017 season; 175.88 ± 179.29 g in the 2018 season), in contrast to wild trees (29.55 ± 25.50 g in the 2017 season; and 63.05 ± 53.25 g in the 2018 season). These differences were statistically significant (p = 0.003; p = 0.008) for both seasons and independent from the effect of the environmental variables analyzed (Table 6).

Table 5.

Structural variables of Bursera bipinnata in wild and managed trees.

Table 6.

Average copal resin production in wild and managed trees in two sampling seasons, as well as the effect of environmental variables (average temperature and relative humidity).

The tapping intensity will also depend on how fast resin exudes, which implies great knowledge and technical skill to identify the resiniferous conduits. According to the copaleros, this process is known as “calentar” or warming the tree and implies identifying the level of ramifications needed to make incisions. Resin extraction of B. bipinnata is carried out only during the rainy season, given the marked seasonality of the TDF, conditioning the tapping season to a determined period, after which trees enter latency and must be left to rest.

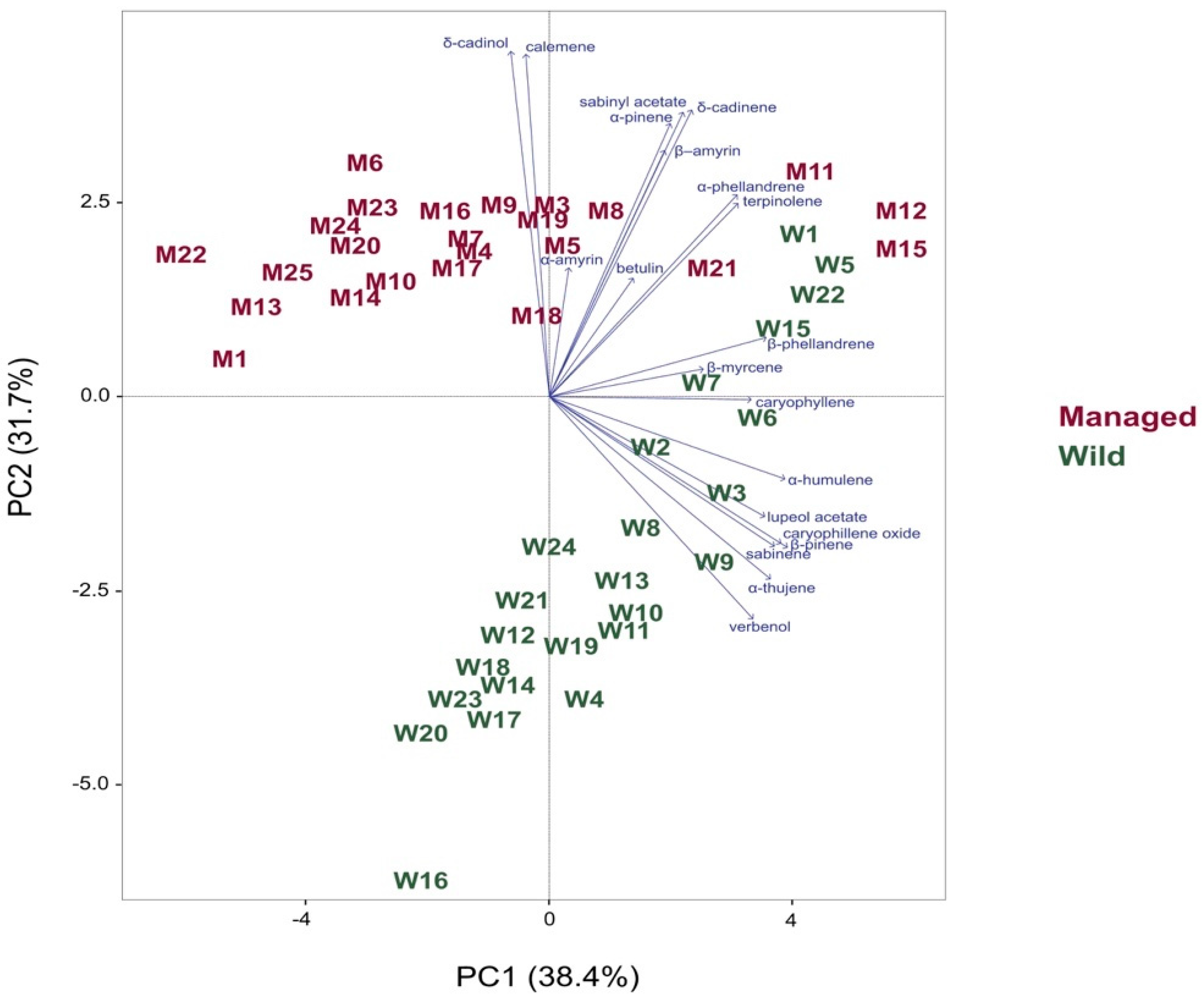

3.5. Characterization of Resin Quality

Twenty organic volatile compounds were found, 16 of them being responsible for the resin’s scent and four for its thickness. The greatest concentrations correspond to α-phellandrene (scent), β-amyrin, and betulin (thickness). Wild trees possess greater percentages of α-phellandrene; in contrast, managed trees have greater percentages of β-amyrin and betulin (thickness). Table 7 shows the significant differences for the percentage of compounds concentration between managed and wild trees. It can be observed that managed trees possess greater percentages of δ-cadinene, δ-cadinol, β-myrcene (scent), and β-amyrin (thickness). At the same time, wild trees had greater percentages of β-pinene, sabinyl acetate, caryophyllene (scent), and lupeol acetate (thickness).

Table 7.

Profile of volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds of the resin of wild and managed individuals of Bursera bipinnata. Compounds are listed in order of elution from an HP-5MS column. RI exp, retention index on HP-5MS obtained experimentally. RI, theo retention index was obtained from the literature (see Experimental Section).

On the other hand, the PCA explains 70.1% of the variation in the first two components, if ordered per management type, according to the actual organic volatile compounds’ percentage. Therefore, the second principal component explains the distinction between managed and wild trees. In Figure 8, managed trees are ordered at the top of the plot and the wild ones in the lower part. The variables that support the separation of wild individuals from managed ones are δ-cadinol, calemene, δ-cadinene, sabinyl acetate, α-pinene, and β-amyrin. These first five compounds give copal resin its scent, and the last one gives copal resin its thickness. Therefore, managed copal trees have a greater percentage of δ-cadinol, calemene, δ-cadinene, sabinyl acetate, α-pinene, and β-amyrin compared to wild trees (Figure 8; Table 8).

Figure 8.

Spatial order as a result of the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) for wild and managed trees of B. bipinnata copal trees, considering the quantity of compounds present in each individual.

Table 8.

Weight of each variable (volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds) of the first two principal components.

4. Discussion

4.1. Copal Management Strategies and Their Rationale

B. bipinnata receives various types of management practices, which are along an intensity gradient. In situ practices in forest and agroforestry systems have the main purpose of increasing the quantity of individuals with desirable attributes. This constitutes a frequent practice in Mesoamerica [46] and has mainly been registered for some edible tree species [5,47,48]. Our study is an effort to register strategies in species with ritual purposes. In Northeast Africa, diverse species of the genus Boswellia and Commiphora are harvested for resin in arid landscapes, where they are promoted and protected, among other in situ management strategies [49,50]. In Indonesia, several species of the genus Styrax L., whose resin is tapped, are currently managed in large plantations, although it has been recognized that these production systems have a previous history of silvicultural management [51].

The ex situ management of copal often implies the transplanting of seedlings, young plants, and vegetative parts, and even seeds sowing. The same has been registered for Boswellia papyrifera (Caill. Ex Delile) Hochst. [52] and for Senegalia senegal (L.) Britton [53], where reproduction using stakes has the purpose of accelerating growth, shortening time, and assuring the propagation of individuals with high resin yields [14]. Moreover, those who use this propagation technique are aware that this method does not guarantee that offspring will possess the same attributes selected in the parent trees.

At the same time, planting of seeds of both species constitutes a strategy to assure resin production through management intensification in anthropic landscapes. Mena [28] reports for the study area that B. bipinnata has higher densities in agroecosystems and systems transformed by humans compared to the low densities in wild vegetation [54]. This can express people’s worrisome interest for having high densities of desired species [51], and that in order to achieve this, they must transform natural spaces, adapting them to have a higher capacity to produce elements valued by people. This situation is similar to that reported in Ethiopia with incense and myrrh-producing species such as S. senegal, Vachellia seyal (Delile) P.J.H.Hurter, B. papyrifera, Boswellia neglecta S.Moore, Boswellia rivae Engl., Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl., and Commiphora guidotti Chiov. ex Guid. [50]. However, this contrasts with reports for species that produce latex, such as Castilla elastica Cerv., where no management practices are reported because, according to the perception of people, these trees germinate on their own and are very abundant [55]. This reinforces the perception that as soon as resources seem to be at risk, the practices and the intensity of management of valued species increase [8,18].

In addition, in B. bipinnata, management practices are also done at the landscape level, where copal is a central part of an agroforestry system where selection and propagation processes are performed with high intensity. In addition to the economic benefits of having a greater spatial availability of the resource, at the landscape level, the agroforestry practices documented for B. bipinnata allow connectivity between patches of wild vegetation, with trees acting as windbreaks that conserve the soils, capture humidity, and reduce insolation (Figure 5). Additionally, isolated trees, particularly those of animal-dispersed species such as Bursera spp. [56,57], promote connectivity in agriculture–forest interfaces, as they attract animal dispersers operating as functional stepping stones across such landscapes [58]. The management of resiniferous species in agroforestry systems is strongly promoted by several international agencies and constitutes notable efforts from public policy in many countries [59]. Such is the case in Asia and Africa for S. senegal, Faidherbia albida (Delile) A. Chev., Boswellia serrata Roxb., Canarium strictum Roxb., Commiphora wightii (Arn.) Bhandari, Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub., Garcinia kola Heckel, and Ocimum gratissimum L., as a strategy to stop deforestation, land degradation due to agriculture and cattle, and also to offer economic alternatives that root people to their territories [53,60,61,62].

In some Latin American countries, several species that produce resin, gum, or latex, have been promoted through agroforestry systems, some for hundreds of years, as is the case of B. copallifera [63,64], B. linanoe [65,66], Manilkara zapota (L.) P.Royen [67,68], Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.juss.) Müll.Arg. [69], and Protium copal (Schltdl. & Cham.) Engl. [70,71,72,73]. These anthropogenic landscapes have high biological diversity because of long selection and manipulation processes carried out consciously or unconsciously by humans in in situ environments throughout generations [4,63].

Therefore, this is a confirmation that copal management strategies and practices are intimately linked to the initial worry to increase the spatial and temporal availability of plant resources of cultural and economic importance [18].

4.2. Artificial Selection Criteria

In B. bipinnata, human selection of the quantity of resin produced per individual is the main criterion for favoring trees in the wild, or to tolerate, promote, protect, or plant them in agroecosystems or silvicultural management. This has been reported for some species of the Burseraceae family, such as P. copal, Bursera submoniliformis Engl., and B. linanoe [71,74,75]. In this study, we documented that for B. bipinnata, human selection is directed to diverse utilitarian attributes, such as the yield, scent, color, and consistency of resin (Table 4). Copal managers identify trees with high resin production according to the strength and size of the stem, as reported for P. copal, Clusia Plum. ex L. sp., B. submoniliformis, and H. brasiliensis [69,70,74,76]. For S. senegal, Ladipo [53] reports that selection is done based on the growth rate, resistance to drought, high yield, and resistance to plagues and diseases.

For B. bipinnata, we also registered in greater depth that selective pressures include the identification of individuals with desirable utilitarian attributes. This can result in more individuals with adequate attributes being kept in wild vegetation or in agroforestry systems. On the contrary, if they do not possess desired attributes, they are eventually eliminated. This has been documented for various edible and medicinal species in Mesoamerica [4], and particularly in long-lived management species such as Crescentia cujete L. in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico [77,78].

4.3. Association between Management and Resin Production

According to the results, for B. bipinnata, we found a linear relationship between the size of trees (expressed as height, cover, and DBH) and resin yield; that is: trees with larger canopy cover and trunk diameter yield more resin. This is a tendency registered for many species but is particularly clear in B. papyrifera [79,80,81] and in P. copal [82]. We registered a yield between 31 and 190 g of resin per tree in both types of management. The latter matches with that reported by Cruz et al. [26], who estimate that B. bipinnata produces on average 174 g per tree. In contrast, Cruz-Cruz et al. [83] estimate a slightly higher average yield of 313 g of resin. B. copallifera and B. glabrifolia (Kunth) Engl. produce a slightly higher yield of 260 and 280 g, respectively.

We also found that managed B. bipinnata trees produced three to six more times the quantity of resin than wild trees (Table 6). Thus, the traditional management of B. bipinnata appears to act by eliminating those individuals that produce little resin and promoting very actively the propagation of individuals that produce large amounts of resin. This is perhaps one of the most important findings, for it confirms the hypothesis that in situ management promotes the presence of individuals with higher resin yields, due to a long history of selection through time.

However, the resin quantity produced by B. bipinnata is exceptionally low compared to other Burseraceae species. For example, B. papyrifera registers a production between 840 and 3000 g of resin per tree [49,81,84]; P. copal from 16 to 308 g [82]; and Styrax sp. from 200 to 1000 g [51]. These differences are probably related to several factors, mainly the size of each of the species. B. bipinnata reaches relatively small heights, between 3 and 6 m. In contrast, B. papyrifera and P. copal can reach heights from 6 to 12 m and from 20 to 30 m, respectively.

Other factors that influence resin yields are the season, the duration, and the intensity of harvest. For B. bipinnata, traditional management establishes that trees can only be harvested once the rainy season has started, after flowering and for a period of three months (July to October). This contrasts with B. papyrifera, which can be harvested for a period of more than six months and is harvested during the dry season [52,81]. Farmers let it rest during the rains, because it is thought that resin can wash off, affecting its quality [49]. P. copal is harvested in the dry season, during a period from 4 to 8 months, depending on the region and culture of those who manage it [82,85]. C. wightii is harvested during the dry season, surely expressing other physiological consequences [86]. This is probably related to the capacity to accumulate secondary metabolites, which occurs in the rainy season, right before tapping, as observed for B. papyrifera [84]. An increase in the quantity of latex in H. brasiliensis is also reported, because they are grown in plantations, a condition that allows them to absorb more CO2 compared to trees that grow in places with more shade [87].

In species such as M. zapota, S. senegal, and Prosopis spp., the production of resin and latex is often related to environmental variables, mainly to temperature and relative humidity [62,88]. However, according to the environmental data of the six management units studied, the differences in copal resin production for B. bipinnata are due to management and not to environmental variables (Table 6); therefore, it is possible to assert that human management is responsible for such differences in resin yields. Thus, B. bipinnata trees that produce greater resin quantities do so as a result of intensive and non-random selection processes [81], where yield turns out to be a key factor overall, because this is an NTFP whose commercialization is based on the kilograms of resin extracted [89].

Nussinovitch [23] observes that many species whose exudates and resins are extracted often do not produce enough quantities to extract, regardless of being healthy and growing in favorable environments (Climate and soil). An explanation has been that under mechanic stress conditions, production can increase, especially when damage has been done to the bark [90]. This has been documented for B. papyrifera where large resin quantities are yielded during the first years of harvest [91]. Ballal et al. [62] also report that the trees of S. senegal produce greater resin quantities when harvest is intensified. This can be associated to the formation of new conduits as a response to increased tapping rates [23,92].

Nevertheless, when the rates of harvest are increased and if tapping of the tree continues after reaching the maximum yield, the yield starts to decrease and can even lead to death [84]. Therefore, it is important to consider the harvest method and the post-harvest treatment. For B. bipinnata, copaleros have it clear that making more incisions than can be tolerated by the tree may compromise next year’s yields or the tree itself.

Purata [24] mentions that a greater harvest rate can produce more resin yields; however, it can also hamper growth, as well as the production of flowers and fruits [69], as observed in several Prosopis species where the gum exudate increases after the fruits have matured [93]. In future studies, it would be relevant to assess the implications of extractive practices on the reproductive biology of the copal tree, particularly the trade-off between resources allocation for plant protection vs. reproduction, contributing to a more precise evaluation of the use of this resin and its long-term sustainability in diverse regions of Mexico. Our research offers evidence that management can also lead to differences in some physiological parameters, such as the quantity of resin yielded and long life cycles in species with ritual uses.

4.4. Organic Compounds in Copal Resin and Their Potential Association with Management

The composition of organic compounds in B. bipinnata (Table 7) is similar to that reported for other Bursera species, mostly with B. graveolens (Kunth) Triana & Planch., B. morelensis Ramírez, B. schlechtendalii Engl., B. simaruba (L.) Sarg., B. tomentosa (Jacq) Triana & Planch., and B. tonkinensis (Guillaumin) Engl. [37,42,94,95,96]. It is also similar to compounds identified in Protium spp., but it shows important differences with the compounds reported for the genera Boswellia, Commiphora, and Aucoumea Pierre [96].

Contrary to our results, Case et al. [97] found that the majority of organic compounds in B. bipinnata are germacrene, α-copaene, β-caryophyllene, and β-bourbonene. Similarly, Lucero et al. [38] identify nine organic compounds, of which only three coincide with our findings: α-amyrin, β-amyrin, and lupeol. Similar results presented by Gigliarelli et al. [98] note that although B. bipinnata is a species that is chemically variable, α-pinene can be identified as one of its main components. In contrast, our research found that α-pinene ranked 12th among the 20 compounds identified.

These differences can be due to various reasons, such as the taxonomical identification, but mainly to the copal samples condition. As observed by Gigliarelli et al. [98], resin that has just been collected is different in terms of the presence of chemical composition, when compared with resin that has been harvested in the past months or has been stored for years. Some reports of the identification of organic compounds for B. bipinnata have been done with samples of resin that had been bought in markets and stored for many years [97,98] and even obtained from archeological sites that are one hundred years old [38]. These differences may also be due to confusion regarding the taxonomic identity of copal species. For example, it is very common to mistake B. bipinnata with Bursera stenophylla Sprague & L.Riley [99]; therefore, the botanical distinction may not be clear [98]. These differences can also happen because often, different species have the same common name, as in the case of “copal blanco”, which is a generic name used for at least two copal species, such as B. copallifera and B. bipinnata [97].

Furthermore, although both B. bipinnata populations (wild and managed) presented the same compounds, these were different in proportion and concentrations. In managed trees, in addition to the three compounds mentioned above, there exists a very important proportion of α-amyrin. In contrast, in wild trees, caryophyllene has an outstanding place. According to Table 8, five compounds allow ordering copal trees according to the type of management (Figure 8), which are all related to substances that confer scent (δ-cadinol, calemene, δ-cadinene, sabinyl acetate, α-pinene), as well as one that gives it its consistency (α-amyrin). This suggests that managed trees possess higher percentages of these five compounds (scent) when compared to wild trees. The latter may mean that management is modifying the abundance of organic compounds that give copal its scent. These processes could be a result of the selection of attributes that are desirable in this resource, as suggested by Carrillo-Galván et al. [10] and Bautista et al. [7], who found that human selection may be generating changes in the chemical profile of secondary metabolites.

Our research concurs with others made on aromatic plants that found differences in the chemical composition of managed individuals compared to wild individuals, based on their utilitarian attributes [10,100], which can augment the desired phenotypes and even eliminate non-desired phenotypes [5].

4.5. Traditional Management and Domestication of Bursera Bipinnata

Our results suggest that driven by its prolonged cultural importance and use, B. bipinnata is in a domestication process [24,25,26,27]. One key motivation to manage and eventually domesticate these plants is to ensure the availability of the resource and eventually improve its quality [4]. The selection of trees with scented resin and abundant yields reflect copaleros’ concerns, whose strategies seek to increase the frequency of trees with these desirable phenotypes.

We consider the traditional management of B. bipinnata as part of a domestication process that has transited through at least three of four phases of co-evolutionary plant–human interaction according to Wiersum [101,102]. These are (a) the collection of products from their natural vegetation, (b) the conscious management of individuals with useful attributes, promoting their production capacity through concrete practices and strategies, and (c) the planting of wild trees carefully selected [50]. All these phases can be observed in B. bipinnata and other resiniferous species around the world [51,81,92,97], where some of them are grown in plantations, with intensive genetic improvement efforts as part of the process [103]. In this way, silvicultural management of B. bipinnata and its promotion in agroforestry systems should be considered part of a complex domestication process that satisfies production needs and ecological concerns [104]. This argument contradicts that which establishes that traditional harvest practices affect the viability of trees whose resin is extracted [105]. In B. bipinnata, copaleros have promoted and encouraged the productive restoration of the TDF, increasing its population density and with this, enhancing ecosystem services, especially provision services, as documented for other resiniferous species such as B. papyrifera [102]. Therefore, we believe that the domestication of B. bipinnata strengthens ecosystem resiliency by reducing its degradation, strengthening its ecological integrity, conserving key elements, and fulfilling human needs.

5. Conclusions

This investigation revealed that B. bipinnata trees that receive some type of management produce a greater quantity of resin and of better quality in contrast to wild trees. Copal management in Mexico’s central–southern region has implied intensive selective processes through hundreds of years, which are associated to silvicultural and agrosilvicultural management practices. This has determined an increase in the frequency of trees that produce greater resin yields, with stronger scent and colors that are demanded by markets and consumers in the copal-producing regions. The management practices involve knowledge and dynamic techniques that are still relevant. This has resulted in a differentiation of wild and managed individuals, as well as in domestication processes in a ritual-purpose species.

Our research suggests new inquiry lines aimed at understanding the agroforestry system in which copal is immersed and the landscape matrix in which it is found. Trees with favorable phenotypes that are managed in this agroforestry system maintain direct connectivity to surrounding forests, with important consequences at the landscape level, for the conservation of the TDF, its elements, and the environmental contributions it provides. Therefore, shedding light on and documenting traditional management techniques of resiniferous species in Mexico can contribute to maintaining people’s livelihoods and conserving the forests.

Author Contributions

I.A.-F., B.M.-A., K.M.A.-D. and J.B. conceived of and designed the study. I.A.-F., L.S.-M., L.B.-R. and I.T.-G. conducted the fieldwork. I.A.-F., Y.M.G.-R. and F.J.E.-G. conducted work in the lab. L.G.-C., S.C. and J.B. analyzed the data. J.B., A.C., A.I.M.-C. and J.A.S.-H. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed with resources from the CONACyT’s Red Temática Productos Forestales No Maderables: aportes desde la etnobiología para su aprovechamiento sostenible (Thematic Network on Non Timber Forest Products: ethnobiological contributions for their sustainable management—Research Projects 271837, 280901, 293914).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the copaleros and the inhabitants of Los Sauces community in Tepalcingo Municipality, in the state of Morelos, Mexico, for their support and availability and for being part of this research; in particular, we’d like to thank Margarito Tajonar, Estrella Cadenas and Doña Vero for their hospitality. We would also like to thank the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos (UAEM), and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matos-Moctezuma, E. Mesoamerica Antigua; Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado: Tabacalera, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Xolocotzi, E. Aspects of plants domestication in Mexico: A personal view. In Biological Diversity of Mexico: Origins and Distribution; Ramamoorthy, T.P., Bye, R., Lot, A., Fa, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 733–756. ISBN 978-019-506-674-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bye, R. The Role of Humans in the Diversification of Plants in Mexico. In Biological Diversity of Mexico: Origins and Distribution; Ramamoorthy, T.P., Bye, R., Lot, A., Fa, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 707–731. ISBN 978-019-506-674-6. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, A.; Caballero, J.; Mapes, C.; Zárate, S. Manejo de la vegetación, domesticación de plantas y origen de la agricultura en Mesoamérica. Bol. Soc. Bot. Méx. 1997, 61, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Otero-Arnaiz, A.; Pérez-Negrón, E.; Valiente-Banuet, A. In situ management and domestication of plants in Mesoamerica. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanckaert, I.; Paredes-Flores, M.; Espinosa-García, F.; Pinero, D.; Lira, R. Ethnobotanical, morphological, phytochemical and molecular evidence for the incipient domestication of Epazote (Chenopodium ambrosioides L.: Chenopodiaceae) in a semi-arid region of Mexico. Genet. Resoures Crop Evol. 2011, 59, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, L.A.; Parra, F.; Espinosa-García, F.J. Efectos de la domesticación de plantas en la diversidad fitoquímica. In Temas Selectos de Ecología Química de Insectos; Rojas, J.C., Malo, E.A., Eds.; El Colegio de la Frontera Sur: Lerma Campeche, Mexico, 2012; pp. 253–267. ISBN 978-607-842-972-1. [Google Scholar]

- Blancas, J.; Casas, A.; Pérez-Salicrup, D.; Caballero, J.; Vega, E. Ecological and sociocultural factors influencing plant management in Nahuatl communities of the Tehuacan Valley, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueredo-Urbina, C.J.; Casas, A.; Torres-García, I. Morphological and genetic divergence between Agave inaequidens, A. cupreata and the domesticated A. hookeri. Analysis of their evolutionary relationships. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Galván, G.; Bye, R.; Eguiarte, L.E.; Cristians, S.; Pérez-López, P.; Vergara-Silva, F.; Luna-Cavazos, M. Domestication of aromatic medicinal plants in Mexico: Agastache (Lamiaceae)—An ethnobotanical, morpho-physiological, and phytochemical analysis. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, A.; Vázquez, M.; Viveros, J.; Caballero, J. Plant management among the Nahua and the Mixtec in the Balsas River Basin, Mexico: An ethnobotanical approach to the study of plant domestication. Hum. Ecol. 1996, 24, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Caballero, J. Traditional Management and Morphological Variation in Leucaena esculenta (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) in the Mixtec Region of Guerrero, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 1996, 50, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.; Casas, A.; Cortes, L.; Mapes, C. Patrones en el conocimiento, uso y manejo de plantas en pueblos indígenas en México. Estudios Atacameños 1998, 16, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, J.; Casas, A.; Rangel-Landa, S.; Moreno-Calles, A.; Torres, I.; Pérez-Negrón, E.; Solís, L.; Delgado-Lemus, A.; Parra, F.; Arellanes, Y.; et al. Plant Management in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2010, 64, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapes, C.; Caballero, J.; Espitia, E.; Bye, R. Morphophysiological variation in some Mexican species of vegetable Amaranthus: Evolutionary tendencies under domestication. Genet. Resoures Crop Evol. 1996, 43, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Ramírez, L.A.; Bravo-Aviléz, D.; Fornoni, J.; Valverde, P.L.; Rendón, A. Variación morfológica en Anoda cristata en la Montaña de Guerrero. In Especies Vegetales Poco Valoradas: Una Alternativa Para la Seguridad Alimentaria; Mera, L.M., Castro, D., Bye, R., Eds.; UNAM-SNICS-SINAREFI: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2011; pp. 115–126. ISBN 978-607-022-589-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bye, R.; Linares, E. Continuidad y aculturación de plantas alimenticias: Los quelites especies subutilizadas de México. In Especies Vegetales Poco Valoradas: Una Alternativa Para la Seguridad Alimentaria; Mera, L.M., Castro, D., Bye, R., Eds.; UNAM-SNICS-SINAREFI: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2011; pp. 11–22. ISBN 978-607-022-589-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Landa, S.; Casas, A.; García-Frapolli, E.; Lira, R. Sociocultural and ecological factors influencing management of edible and non-edible plants: The case of Ixcatlán, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán-Rodríguez, L.; Manzo-Ramos, F.; Maldonado-Almanza, B.; Martínez-Ballesté, A.; Blancas, J. Wild medicinal species traded in The Balsas Basin, Mexico: Risk analysis and recommendations for their conservation. J. Ethnobiol. 2017, 37, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cházaro, M.; Mostul, B.; García, F. Los copales mexicanos (Bursera spp.). Bouteloua 2010, 7, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rzedowski, J.; Guevara-Féfer, F. Burseraceae. Flora del Bajíoy de Regiones Adyacentes. Fascículo 3; Instituto de Ecología, A. C., Centro Regional del Bajío: Pátzcuaro, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbazghi, W.; Rijkers, T.; Wessel, M.; Bongers, F. Distribution of the frankincense tree Boswellia papyrifera in Eritrea: The role of environment and land use. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinovitch, A. Plant Gum Exudates of the World. Sources, Distribution, Properties, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-142-005-223-7. [Google Scholar]

- Purata, S.E. Algunos usos del copal. In Uso y Manejo de Los Copales Aromáticos: Resinas y Aceites; Purata, S.E., Ed.; Colección Manejo Campesino de los Recursos Naturales: México, D.F., Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Linares, E.; Bye, R. El copal en México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Biodiversitas 2008, 78, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, A.; Salazar, M.L.; Campos, O.M. Antecedentes y actualidad del aprovechamiento de copal en la Sierra de Huautla, Morelos. Revista de Geografía Agrícola 2006, 37, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Montúfar, A. El copal: Resina sagrada prehispánica y actual. In Flor y flora. Su uso ritual en Mesoamérica. México: Secretaría de Educación del Gobierno del Estado de México; Albores, B., Ed.; El Colegio Mexiquense, A.C.: Zinacantepec, Mexico, 2015; pp. 86–98. ISBN 978-607-495-412-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, F. Estrategias Ecológicas y Culturales Para Garantizar la Disponibilidad de Productos Forestales no Maderables: Árboles Medicinales en la Selva Baja del Sur de Morelos. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- García, E. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen; Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SEDATU. Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario Territorial y Urbano Padrón e Histórico de Núcleos Agrarios. Registro Agrario Nacional. 2020. Available online: https://phina.ran.gob.mx/index.php (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Rzedowski, J. Vegetación de México, 1st ed.; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: México, D.F. Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Almanza, B. Aprovechamiento de los recursos florísticos de la Sierra de Huautla Morelos, México. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Censo de Población y Vivienda. 2010. Available online: https://www.inegi.org (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Martin, G. Etnobotánica: Manual de métodos. Nordan-Comunidad; WWF-UK-UNESCO-Kew Royal Botanic Garden: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R. Métodos de Investigación en Antropología. Abordajes Cualitativos y Cuantitativos, 2nd ed.; Altamira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Villa-Ruano, N.; Pacheco-Hernández, Y.; Becerra-Martínez, E.; Zárate-Reyes, J.A.; Cruz-Durán, R. Chemical profile and pharmacological effects of the resin and essential oil from Bursera slechtendalii: A medicinal “copal tree” of southern Mexico. Fitoterapia 2018, 128, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero Gómez, P.; Mathe, C.; Vieillescazes, C.; Bucio, L.; Belio, I.; Vega, R. Analysis of Mexican reference standards for Bursera spp. resins by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and application to archaeological objects. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Acevedo, A.; Serrano-Uribe, A.; Parra-Navas, X.J.; Olivares-Escobar, L.A.; Niño-Porras, M.E. Análisis multivariable y variabilidad química de los metabolitos volátiles presentes en las partes aéreas y la resina de Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana & Planch. de Soledad (Atlántico, Colombia). Bol. Lat. Caribe Plant Med. Aromat. 2013, 12, 322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-193-263-321-4. [Google Scholar]

- Linstrom, P.J.; Mallard, W.G.J. The NIST chemistry WebBook: A chemical data resource on the internet. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2001, 46, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Martínez, C.A.; Rosas-López, R.; Rodríguez-Monroy, M.A.; Canales-Martínez, M.M.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Jiménez-Alvarado, R. Chemical Composition and in vivo Anti-inflammatory Activity of Bursera morelensis Ramírez Essential Oil. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2014, 17, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, Y.M.; Torres-Gurrola, G.; Meléndez-González, C.; Espinosa-García, F.J. Phenotypic variations in the foliar chemical profile of Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, A.; Veall, M.A.; Boivin, N.; Horton, M.; Kotarba-Morley, A.; Fuller, D.Q.; Fenn, T.; Haji, O.; Matheson, C.D. Use of Zanzibar copal (Hymenaea verrucosa Gaertn.) as incense at Unguja Ukuu, Tanzania in the 7-8th century CE: Chemical insights into trade and Indian Ocean interactions. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 53, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. Improving your data transformations: Applying the Box-Cox transformation. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn, J. El Te’lom huasteco: Presente, pasado y futuro de un sistema de silvicultura indígena. Biotica 1983, 8, 315–331. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, E.; Casas, A. Morphological variation and domestication of Escontria chiotilla (Cactaceae) under silvicultural management in the Tehuacán Valley, Central Mexico. Genet. Resoures Crop Evol. 2003, 50, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Calles, A.I.; Casas, A.; García-Frapolli, E.; Torres-Gacía, I. Traditional agroforestry systems of multi-crop “milpa” and “chichipera” cactus forest in the arid Tehuacán Valley, Mexico: Their management and role in people’s subsistence. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 84, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemenih, M.; Teketay, D. Frankincense and miyrrh resources of Ethiopia: I Distribution, production, opportunities for dryland development and research needs. Ethiop J. Sci. J. 2003, 26, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lemenih, M.; Wiersum, K.F.; Woldeamanuel, T.; Bongers, F. Diversity and dynamics of management of gum and resin resources in Ethipia: A trade-off between domestication and degradation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011, 25, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Goloubinoff, M.; Perez, M.R.; Michon, G. Experiences in Benzoin Resin Production in Sumatra, Indonesia. In Conservation, Management and Utilization of Plant Gums, Resins and Essential Oils; Mugah, J.O., Chikamai, B.N., Mbiru, S.S., Casadei, E., Eds.; AIDGUM-FAO-GTZ-TWAS: Nairobi, Kenya, 1997; pp. 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Taye, A. Domesticating Frankincense Tree (Boswellia papyrifera) in the Blue Nile Gorge of Ethiopia; Natural Resources Management: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2002; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ladipo, D. Plant gums, resins and essential oil resources in Africa: Potentials for domestication. In Conservation, Management and Utilization of Plant Gums, Resins and Essential Oils; Mugah, J.O., Chikamai, B.N., Mbiru, S.S., Casadei, E., Eds.; AIDGUM-FAO-GTZ-TWAS: Nairobi, Kenya, 1997; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, B.; Caballero, J.; Delgado, A.; Lira, R. Relationship between use value and ecological importance of floristic resources of seasonally dry tropical forest at the Balsas river basin, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2013, 67, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaylón-Chávez, L.I. Uso y distribución de Castilla elástica (hule) en Zozocolco de Guerrero Veracruz. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de la Peña-Domene, M.; Martínez-Garza, C.; Palmas-Pérez, S.; Rivas-Alonso, E.; Howe, H.F. Roles of birds and bats in early tropical-forest restoration. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Pulido, R.; Rico-Gray, V. Seed Dispersal of Bursera fagaroides (Burseraceae): The effect of linking environmental factors. Southwest. Nat. 2006, 51, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Peña-Domene, M.; Minor, E.S.; Howe, H.F. Restored connectivity facilitates recruitment by an endemic large-seeded tree in a fragmented tropical landscape. Ecology 2016, 97, 2511–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, R.; Shukla, A.; Sing, P. Agroforestry and Livelihood Opportunities from Natural Resins and Gums (NRGS) including Lac. In Agroforestry Research and Development to Improve Livelihood. Nutritional and Environmental Security: Policy, Practice and Impact; Dhyani, S.K., Nayak, D., Rizvi, J., Eds.; Sout Asia Regional Program; World Agroforestry: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Poschen, P. An evaluation of Acacia albida-based agroforestry practices to the Hararghe highlands of Eastern Ethiopia. Agrofor. Syst. 1986, 4, 29–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.R.; Mughogho, S.K. Nutrient cycling by Acacia albida (syn. Faidherbia albida) in Agroforestry systems. In Technologies for Sustainable Agriculture in the Tropics; Ragland, J., Rattan, L., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1993; Volume 56, pp. 97–108. ISBN 978-089-118-118-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ballal, M.E.; El Siddig, E.A.; Efadl, M.A.; Luukkanen, O. Gum arabic yield in differently managed Acacia senegal stands in western Sudan. Agrofor. Syst. 2005, 63, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Calles, A.I.; Casas, A.; Toledo, V.M.; Vallejo, M. Etnoagroforestería en México, los proyectos y la idea del libro. In Etnoagroforestería en México; Moreno-Calles, A.I., Casas, A., Toledo, V.M., Vallejo, M., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: México City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 10–26. ISBN 978-607-02-8164-8. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Salas, N.; Casas, A.; Moreno-Calles, A.I.; Vallejo, M. Plant Management in Agroforestry Systems of Rosetophyllous Forests in the Tehuacán Valley, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Castro, C.; Bonfil, C. Propagation of three Bursera species from cuttings. Bot. Sci. 2013, 91, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Calles, A.I.; Toledo, V.; Casas, A. Los sistemas agroforestales tradicionales de México: Una aproximación biocultural. Econ. Bot. 2013, 91, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flachsenberg, H.; Galletti, H. Forest Management in Quintana Roo, Mexico. In Timber, Tourists, and Temples. Conservation and Development in the Maya Forest of Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico; Primack, R., Barton, D., Galletti, H., Ponciano, I., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 47–60. ISBN 155-963-542-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dussol, L.; Elliott, M.; Michelet, D.; Nondédéo, P. Ancient Maya sylviculture of breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum Sw.) and sapodilla (Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen) at Naachtun (Guatemala): A reconstruction based on charcoal analysis. Quat. Int. 2017, 457, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Bautista, H.; Domínguez-Domínguez, M.; Martínez-Zurimendi, P.; Velázquez-Martínez, A.; Córdova-Ávalos, V. Problemática en los procesos de producción de las plantaciones de hule Hevea brasiliensis Muell Arg. en Tabasco, México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2011, 14, 513–524. [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn, J. Development policy, forests, and peasant farms: Reflections on Huastec-managed forests’ contributions to commercial production and resource conservation. Econ. Bot. 1984, 38, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, V.J.A. Estudio etnobotánico del árbol de Pom [Protium copal, (Schelcht. et Cham.) Engler] en el municipio de Cahabón, Alta Verapaz. Guatemala. Bachelor’s Thesis, Instituto de Investigaciones Agronómicas, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Ciudad de Guatemala, República de Guatemala, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, J.L.; Diemont, S.; Gibbs, J.P.; Stehman, S.; Mendoza-Vega, J. Implications of Mayan agroforestry for biodiversity conservation in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Rosas, N.; Silva-Rivera, E.; Ruiz-Guerra, B.; Armenta-Montero, S.; González, J. Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a tool for biocultural landscape restoration in northern Veracruz, Mexico: A case study in El Tajín region. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, L. Aspectos Socio-Ecológicos Para el Manejo Sustentable del Copal en el Ejido de Acateyaualco, Guerrero. Bachelor’s Thesis, Centro de Investigación en Ecosistemas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Ostoa, G.; González-Bernal, S.; Arellano-Hernández, G. Lináloe (Bursera linanoe (La Llave) Rzedowski, Calderón & Medina), Especie maderable amenazada: Una estrategia para su conservación. Agro Product. 2014, 7, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zenteno-Ruíz, F.S. Referencias botánicas, ecológicas y económicas del aprovechamiento del incienso (Clusia vel. sp. nov., Clusiaceae) en bosques montanos del Parque Nacional Madidi, Bolivia. Ecología en Bolivia 2007, 42, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Duguá, X.; Eguiarte, L.E.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Casas, A. Round and large: Morphological and genetic consequences of artificial selection on the gourd tree Crescentia cujete by the Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Duguá, X.; Pérez-Negrón, E.; Casas, A. Phenotypic differentiation between wild and domesticated varieties of Crescentia cujete L. and culturally relevant uses of their fruits as bowls in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, K.; Muys, B.; Haile, M.; Mitloehner, R. Introducing Boswellia papyrifera (Del) Hoscht. and its non-timber forest product, frankincense. Int. For. Rev. 2003, 5, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbazghi, W.; Bongers, F.; Rijkers, T.; Wessel, M. Population structure and morphology of the frankincense tree Boswellia papyrifera along an altitude gradient in Eritrea. J. Drylands Agric. 2006, 1, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Eshete, A. The Frankincense tree of Ethiopia. Ecology, Productivity and Population Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neels, S. Yield, Sustainable Harvest and Cultural Uses of Resin from the Copal Tree Protium copal; Burceraceae) in the Carmelita Community Forest Concession, Petén, Guatemala. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Britihs Combia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Cruz, M.; Antonio-Gómez, V.M.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Vásquez-Barranco, I.G.; Lagunes-Rivera, L.; Hernández-Santiago, E. Resina y aceites esenciales de tres especies de copal del sur de Oaxaca, México. Rev. Mex. Agroecosistemas 2017, 4, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tolera, M.; Sass-Klaassen, U.; Eshete, A.; Bongers, F.; Sterck, F. Frankincense yield is related to tree size and resin-canal characteristics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 353, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, C.; Makenzi, P.; Chikamai, B.; Luvanda, A.; Muga, M. Traditional ecological knowledge associated with Acacia senegal (Gum arabic tree) management and gum arabic production in northern Kenya. Int. For. Rev. 2010, 12, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, J.R.; Nair, N.; Mohan, H. Enhancement of oleo-gum resin production in Commiphora wightii by improved tapping technique. Curr. Sci. 1989, 58, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers, H.; Chapin, F.; Pons, T. Plant Physiological Ecology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-038-778-341-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, W.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zou, Y.X. Selection for high-resin yield of slash pine and analysis of factors concerned. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis 2007, 29, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hersch-Martínez, P. Commercialization of wild medicinal plants from southwest Puebla, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 1995, 49, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glicksman, M. Gum Technology in the Food Industry; Ademic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Eshete, A.; Teketay, D.; Lemenih, M.; Bongers, F. Effects of resin tapping and tree size on the purity, germination and storage behavior of Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst. Seeds from Metema District, northwestern Ethiopia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 269, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenheim, J.H. Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology and Ethnobotany; Timber Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 088-192-574-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vilela, A.E.; Ravetta, D.A. Gum exudation in South-American species of Prosopis L. (Mimosaceae). J. Arid Environ. 2005, 60, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, H.T.; Huy, T.T.; Lesueur, D.; Bighelli, A.; Casanova, J. Volatile components of Bursera tonkinensis Guill. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2004, 7, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Rojas, L.B.; Aparicio, R.; Marco, L.; Usubillaga, A. Chemical composition of the essential oil from the bark Bursera tomentosa (Jacq) T & Planch. Bol. Lat. Caribe Plant Med. Aromat. 2010, 9, 491–494. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, A.; Dosoky, N.S.; Satyal, P.; Sorensen, A.; Setzer, W.N. The essential oils of the burseraceae. In Essential Oil Research: Trends in Biosynhesis, Analytics, Industrial Applications and Biotechnological Production; Malik, S., Ed.; Springer: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 61–145. [Google Scholar]

- Case, R.J.; Tucker, A.O.; Maciarello, J.M.; Wheeer, K.A. Chemistry and ethnobotany of commercial incense copals, copal blanco, copal oro, and copal negro, of North America. Econ. Bot. 2003, 57, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliarelli, G.; Becerra, J.; Curini, M.; Marcotullio, M.C. Chemical composition and biological activities of fragrant mexican copal (Bursera spp.). Molecules 2015, 20, 22383–22394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzedowski., J.; Medina, R.; Calderón de Rzedowski, G. Inventario del conocimiento taxonómico, así como de la diversidad y del endemismo regionales de las especies mexicanas de Bursera (Burseraceae). Acta Bot. Mex. 2005, 70, 75–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebler, J.; Buettner, A. Quantification of odor active compounds from Boswellia sacra frankincense by stable isotope dilution assays (SIDA) in combination with TDU-GC-MS. Lebensmittelchemie 2015, 69, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersum, K.F. From natural forest to tree crops, co-domestication of forests and tree species, an overview. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1997, 45, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersum, K.F. Domestication of trees or forests: Development pathways for fruit tree production in South-east Asia. In Indigenous Fruit Trees in the Tropics: Domestication, Utilization and Commercialization; Akinnifesi, F.K., Leakey, R., Ajayi, O.C., Sileshi, G., Tchoundjeu, Z., Matakala, P., Kwesiga, F.R., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 70–83. ISBN 978-184-593-110-0. [Google Scholar]

- Addisalem, A.B.; Bongers, F.; Kassahun, T.; Smulders, M.J. Genetic diversity and differentiation of the frankincense tree (Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst) across Ethiopia and implications for its conservation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 360, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, G.; de Foresta, H.; Levang, P.; Verdeaux, F. Domestic forests: A new paradigm for integrating local communities’ forestry into tropical forest science. Ecol Soc. 2007, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijkers, T.; Ogbazghi, W.; Wessei, M.; Bongers, F. The effect of tapping for frankincense on sexual reproduction in Boswellia papyrifera. J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).