Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Differential Rate of Growth of Apparent Demand (DRGAD)

2.2. Wood Balance Analysis (WBA)

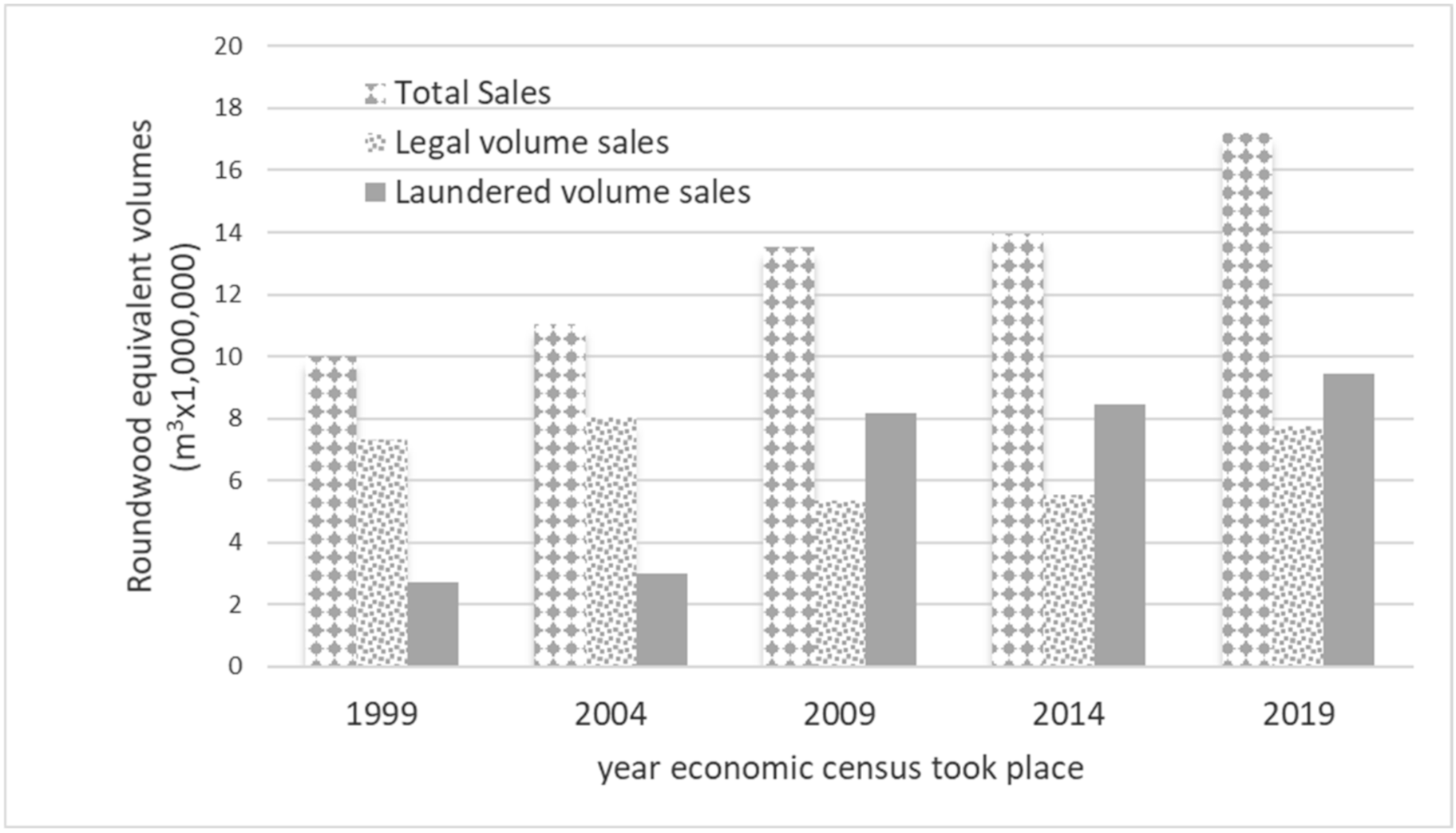

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Robustness of Estimates

- No substitution of timber used in different products. The share of domestic timber used in the three groups of products (pulp/paper, boards, and sawn wood) remains relatively constant throughout the observed period [28]. This suggests no substitution in the use of timber volumes between the different groups of wooden products. This production structure can be confirmed by comparing the share of wooden products produced by the harvest in 1999 and 2018 when legal timber harvest volumes were extremely similar [28].

- Limited technological change: Technological change in the various sawn wood products has been limited. Sawn wood in Mexico is mostly used for the construction (60%) and manufacturing sectors [19,38]. The housing industry in Mexico uses a limited amount of sawn wood as a building material since most formal housing is composed of concrete and bricks. The introduction of new building material (apparent, plastic, and recycled) has had a minimal effect on the demand for sawn wood for this sector since it is mostly used in the building process, as supporting material, scaffolding, and as molding and support material for when concrete is poured. Nevertheless, technological change has been evident in the replacement of wooden boxes and packaging to transport certain agricultural products with plastic boxes. This change has taken place since the 2000s, mainly in agricultural export products, although the use of wooden boxes remains important and will continue to do so in the future given their advantages [41], and as a strategy against climate change mitigation [42]. However, the volumes used in this activity are not high enough to account for the reduction in sawn wood demand.

- Substitution of domestic sawn wood by imported products. AD in timber products has steadily risen since the mid-1990s, and the structure of forest product imports, particularly cellulose and paper (88%), boards (7%), and sawn wood (5%), mainly from the USA, Chile, China, and Brazil, has undergone no significant changes since the mid-1990s [27]. Sawn wood imports skyrocketed at the beginning of the century but have remained low since 2005 (Figure 1b). An additional feature of imports is that a high percentage of conifer sawn wood imports from the United States are processed industrially in companies located on the U.S.-Mexico border and free zones with the USA and returned to that country in the form of finished products. These imported woods are used to manufacture wood moldings, bookshelves, furniture, and frames [43,44,45].

- Since the early 1990s, the country has increased its exports of many products, mainly autos, auto parts, clinical and agricultural products, making it the ninth-largest exporting economy worldwide [46]. This growth in economic activity is associated with the use of large volumes of paper and cardboard for packing, as well as a significant amount of wooden packing boxes and pallets composed of sawn wood. The statistics clearly show an increase in the demand for paper products, but not for products derived from sawn wood.

- Over 35% of the sawn wood produced in Mexico is used in the furniture industry [48]. However, since the turn of the century, this industry has experienced strong growth, particularly in the manufacture of artisanal furniture [49,50]. This largely informal industry has focused the economy of certain small cities on the labor-intensive production of rustic furniture, which has invaded many corners and street markets in most cities in Mexico and even reached overseas markets [51]. This growth in demand for sawn wood is not reflected in the statistics either.

- Overseas demand for certain fruits and vegetables has skyrocketed since the early 2000s, which, in turn, has increased demand for posts and other wooden structures to support fruits and vegetables used in traditional and intensive agricultural systems, such as protected agriculture and vertical farming [52]. This rise in demand for sawn wood is not reflected in the statistics either.

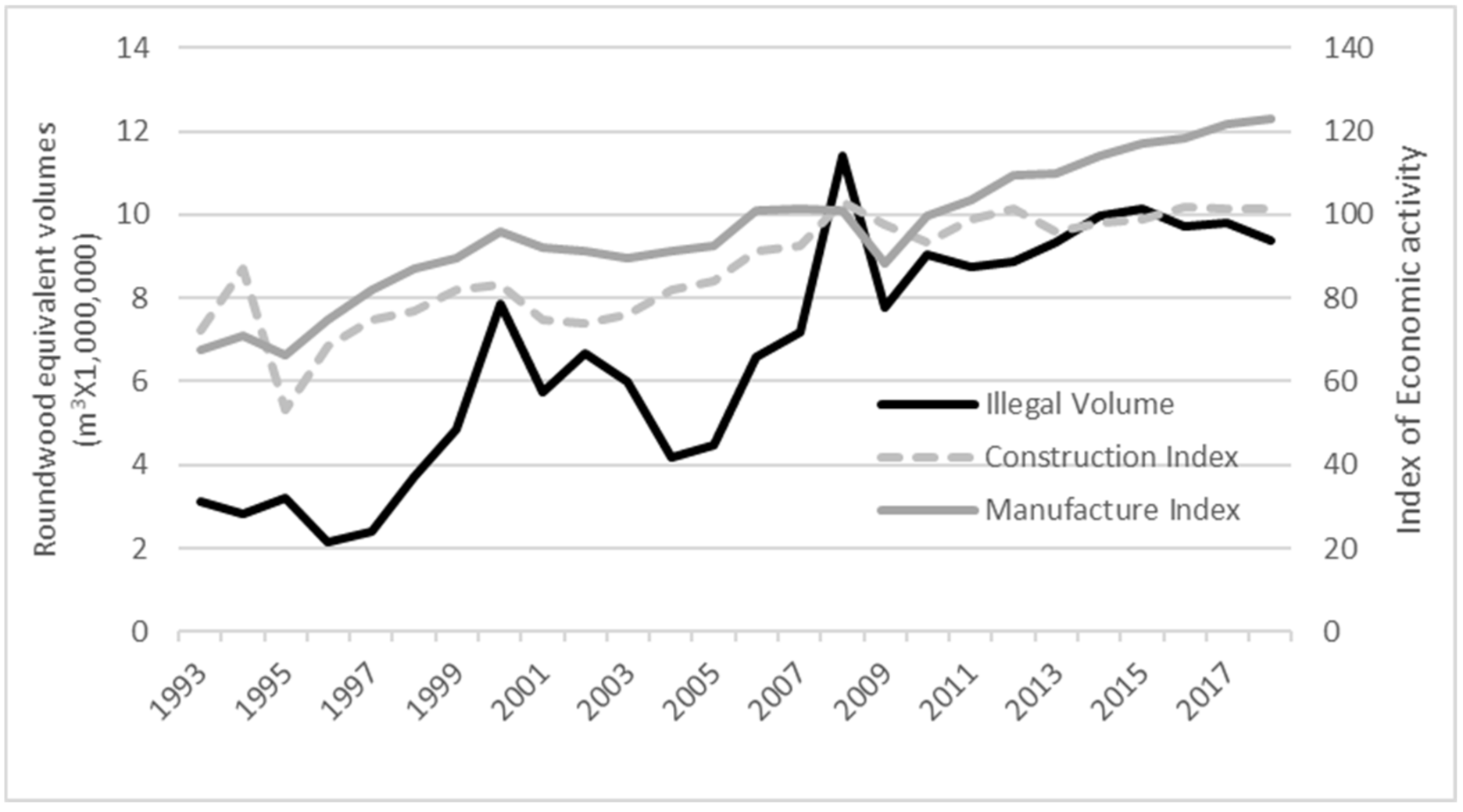

4.2. Relationship between Illegal Logging and Sectors in the Economy

4.3. Illegal Logging as a Driver of the Timber Productivity Trap

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Forest Resource Assessment 2010: Mexico; FAO-ONU Forestry: Roma, Italy, 2012; 121p. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estrategia Nacional de Manejo Forestal Sustentable para el Incremento de la Producción y Productividad (ENAIPROS), 2013–2018; CONAFOR: Jalisco, Mexico, 2013; 58p. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estado que Guarda el Sector Forestal en México; CONAFOR: Jalisco, Mexico, 2019; 408p. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Anzures, F.; Acosta-Mireles, M.; Flores-Ayala, E.; Torres-Rojo, J.M.; Sangerman-Jarquín, D.M.; González-Molina, L.; Buendía-Rodríguez, Y.E. Caracterización de productores forestales en 12 estados de la República Mexicana. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2017, 8, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aceves, T.T.; Fernández, P.G.; Porter-Bolland, L. ¿Qué se Necesita para Avanzar Hacia el Manejo de los Bosques de Niebla Secundarios en México? CCMSS: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2019; 16p. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Rivas, J.S.; Torres-Rojo, J.M.; Lujan-Soto, J.E.; Nava-Miranda, M.G.; Aguirre-Calderón, O.A.; von Gadow, K. Density and Production in the Natural Forests of Durango/Mexico. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2016, 187, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Forestal 2016; SEMARNAT: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2016; 223p. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Estudios de Competitividad (CEC). El Sector Forestal en México: Diagnóstico, Prospectiva y Estrategia; ITAM: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2010; 98p. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible (CCMSS). Un Nuevo Enfoque para Combatir la Tala y el Comercio de Madera Ilegal en México, Nota informativa 33; CCMSS: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2012; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, P.; Cerutti, P.O.; Edwards, D.P.; Lescuyer, G.; Mejía, E.; Navarro, G.; Obidzinski, K.; Pokorny, B.; Sist, P. Multiple and Intertwined Impacts of Illegal Forest Activities. In Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade—Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific, Rapid Response Assessment Report; Kleinschmit, D., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C., Purret, A., Eds.; IUFRO World Series: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, C.R.; Orensanz, L. Revolución y paternalismo ecológico: Miguel Ángel de Quevedo y la política forestal en México, 1926–1940. Hist. Mex. 2007, 57, 91–138. [Google Scholar]

- Almazán-Reyes, M.A. Montes en transición: Acceso y aprovechamiento forestal en el Nevado de Toluca, del Porfiriato a la Posrevolución. Let. históricas 2019, 20, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa-Ortiz, M. Los Bosques de México: Relato de un Despilfarro y una Injusticia; Instituto Mexicano de Investigaciones Económicas: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1958; 165p. [Google Scholar]

- Vitz, M. La ciudad y sus bosques: La conservación forestal y los campesinos en el valle de México, 1900–1950. Est. Hist. Mod. Contemp. México 2012, 43, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuela, A. Illegal logging and local democracy: Between communitarianism and legal fetishism. Amb. Soc. 2006, 9, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merino, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Ortiz, G.; García, A. Estudio Estratégico Sobre el Sector Forestal Mexicano; CCMSS: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2008; 215p. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-Deloya, M. La verdadera cosecha maderable en México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2010, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, I. El Mercado Ilegal de la Madera en México, Nota Informativa 16; CCMSS: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2007; 7p. [Google Scholar]

- INDUFOR, O.Y. SEMARNAP: Plan Estratégico Forestal Para México 2020; INDUFOR: Helsinki, Finland, 2000; 170p. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Garduño, E.; Gómez-García, E.; Campos-Gómez, S. Prevalence trends of wood use as the main cooking fuel in Mexico, 1990–2013. Salud Púb. México 2017, 19, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, J. Sustainable Timber Trade: Are Discrepancies in Trade Data Reliable Indicators of Illegal Activities? In Proceedings of the IV International Conference on Agricultural Statistics. Advancing Statistical Integration and Analysis., Beijing, China, 22–24 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Peng, R. Timber Flow Study: Export/ImportDiscrepancy Analysis. China vs. Mozambique, Cameroon; IIED: London, UK, 2015; 41p. [Google Scholar]

- Jianbang-Gan, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.; Andrighetto, N.; Dawson, T. Quantifying Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade. In Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade—Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific, Rapid Response Assessment Report; Kleinschmit, D., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C., Purret, A., Eds.; IUFRO World Series: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Mansourian, S.; Wildburger, C.; Purret, A. Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade–Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific Rapid Response Assessment Report; IUFRO World Series: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Volume 35, 148p. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; CAF; ECLAD; European Comission. Latin American Economic Outlook 2019: Development in Transition; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; 220p. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, S.; Macfaul, L. Illegal Logging and Related Trade: Indicators of the Global Response; Chatham House: London, UK, 2010; 132p. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). FAOSTAT. 2020. Available online: www.fao.org/faostat/ (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Anuarios Estadísticos Forestales; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censos Económicos; INEGI: Mexico, 2020; Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ce/2019/ (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONFOR). SIPRE—Sistema de Precios de Productos Forestales Maderables; CONAFOR: Jalisco, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Forestal (INFOR). Actualización de Factores de Conversión en el Sector Forestal de Chile: Primera Etapa; INFOR, Grupo de Economía y Mercado: Santiago, Chile, 2009; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Zavala-Zavala, D.; Hernández-Cortés, R. Análisis del rendimiento y utilidad del proceso de aserrío de trocería de pino. Madera Bosques 2000, 6, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapolsky, E.J.; Schmukler, S.L. Crisis management in capital markets: The impact of Argentine policy during the Tequila effect. In World Bank Economists’ Forum; World Bank Pub.: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Calva, J.L. México: La estrategia macroeconómica 2001–2006. Promesas, resultados y perspectivas. Prob. Des. 2005, 36, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calva, J.L. La economía mexicana en su laberinto neoliberal. Trimest. Económico 2019, 86, 579–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, J.; Alvarado, C. México: Estabilidad de precios y limitaciones del canal de crédito bancario. Prob. Des. 2015, 46, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapela, G. Competitividad de las Empresas Sociales Forestales en México: Problemas y Oportunidades en el Mercado Para las Empresas Sociales Forestales en México; CCMSS, UACH, USAID: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, A.; Gomes, D.; Sousa, R.; Vidal, N.; Hojer, R.F.; Arguelles, L.A.; Kaatz, S.; Martin, A.; Donini, G.; Scherr, S.; et al. Community forest enterprise markets in Mexico and Brazil: New opportunities and challenges for legal access to the forest. J. Sust. For. 2008, 27, 87–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProChile. PMP Estudio de Mercado Componentes de Madera en México 2014; ProChile: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2014; 18p. Available online: https://www.prochile.gob.cl/wp-content/files_mf/1426683338PMP_Mexico_Manufacturas_Madera_2014.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Albrecht, S.; Brandstetter, P.; Beck, T.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Grönman, K.; Baitz, M.; Deimling, S.; Sandilands, J.; Fischer, M. An extended life cycle analysis of packaging systems for fruit and vegetable transport in Europe. Int. J. Life Cycle Assm. 2013, 18, 1549–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, P.; Cardellini, G.; González-García, S.; Hurmekoski, E.; Sathre, R.; Seppälä, J.; Smyth, C.; Stern, T.; Verkerk, P.J. Substitution Effects of Wood-Based Products in Climate Change Mitigation. In Science to Policy 7; European Forest Institute: Sarjanr, Finland, 2018; 27p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehlmann, U.; Schuler, A. The US household furniture industry: Status and opportunities. For. Prod. J. 2009, 59, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Wen, Y.; Kant, S. The global competitiveness of the Chinese wooden furniture industry. For. Pol. Econ. 2009, 11, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. The changing global geography of low-technology, labor-intensive industry: Clothing, footwear, and furniture. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R.; Hidalgo, C.; Bustos, S.; Coscia, M.; Chung, S.; Jimenez, J.; Simoes, A.; Yildirim, M.A. The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; 71p. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). PIB y Cuentas Nacionales: Actividad Industrial. Data Base. 2018. Available online: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/cn/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Klooster, D.; Mercado-Celis, A. Sustainable production networks: Capturing value for labour and nature in a furniture production network in Oaxaca, Mexico. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 1889–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harner, J.P. Elaboración de muebles rústicos en México y su popularidad en los Estados Unidos. Tiempos América 2003, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Tecnológica de la Zona Metropolitana de Guadalajara (UTZMG). Encadenamiento Productivo Forestal—Madera—mueble; Gobierno de Jalisco; UTZMG: Jalisco, Mexico, 2009; 143p, Available online: https://utzmg.edu.mx/transparencia/fraccion_XI/ENCADENAMIENTO_PRODUC_FORESTAL_MADERA_MUEBLE_EDO_JAL.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Pietrobelli, C.; Rabellotti, R. Upgrading to Compete Global Value Chains, Clusters, and SMEs in Latin America; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; 331p. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, P.; Bugarín, R.; Castro, R.; Sánchez-Monteón, A.L.; Cruz-Crespo, E.; Juárez Rosete, C.R.; Santiago, G.A.; Morales, R. Estructuras utilizadas en la agricultura protegida. Fuente 2011, 3, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cubbage, F.W.; Davis, R.R.; Rodríguez-Paredes, D.; Mollenhauer, R.; Kraus Elsin, Y.; Frey, G.E.; Gonzalez Hernandez, I.A.; Albarrán Hurtado, H.; Salas, D.N.C.; Cruz, A.M.S. Community forestry enterprises in Mexico: Sustainability and competitiveness. J. Sust. For. 2015, 34, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres-Rojo, J.M.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Mendoza-Briseño, M.A. Sustainable forest management in Mexico. Curr. For. Rep. 2016, 2, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caballero-Deloya, M. Tendencia histórica de la producción maderable en el México contemporáneo. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Ftales. 2017, 8, 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lopez, G.A.; Antinori, C. Between grassroots collective action and state mandates: The hybridity of multi-level forest associations in Mexico. Cons. Soc. 2018, 16, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Velázquez, R.; Serrano-Gálvez, E.; Palacio-Muñoz, V.H.; Chapela, G. Análisis de la industria de la madera aserrada en México. Madera Bosques 2007, 13, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva-Guzmán, J.A.; Ramírez Arango, A.M.; Fuentes Talavera, F.J.; Rodríguez Anda, R.; Turrado Saucedo, J.; Richter, H.G. Diagóstico de la industria de transformación primaria de las maderas tropicales de México. Rev. Mex. Cien. Ftales. 2015, 6, 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Rojo, J.M.; Amador-Callejas, J. Cap. I. Características de los núcleos agrarios forestales en México. In Desarrollo Forestal Comunitario: La Política Pública; Torres-Rojo, J.M., Ed.; CIDE Coyontura y Ensayo: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2015; pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D.B.; Torres-Rojo, J.M. Chapter VI. Markets and the Economics of Mexican Community Forest Enterprises. In Mexico’s Community Enterprises: Success on the Commons and the Seed for a Good Anthropocene; Bray, D., Ed.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2020; pp. 151–184. [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Rosés, J. Illegal logging in common property forests. Soc. Nat. Res. 2009, 22, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, L.P.; Slayback, D.A.; Jaramillo-López, P.; Ramirez, I.; Oberhauser, K.S.; Williams, E.H.; Fink, L.S. Illegal logging of 10 hectares of forest in the Sierra Chincua monarch butterfly overwintering area in Mexico. Am. Entomol. 2016, 62, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raines, J. The Effectiveness of Natural Protected Areas in Mexico to Reduce Forest Fragmentation and Forest Cover Loss. Master’s Thesis, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; 94p. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas. 2018. Available online: http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/?ag=17 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Pierson, P. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, W.J.; de Boer, F.W. The historical dynamics of social–ecological traps. Ambio 2014, 43, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Solinge, T.B.; Zuidema, P.; Vlam, M.; Cerutti, P.O.; Yemelin, V. Organized Forest Crime: A Criminological Analysis with Suggestions from Timber Forensics. In Illegal Logging and Related Timber Trade—Dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific, Rapid Response Assessment Report; Kleinschmit, D., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C., Purret, A., Eds.; IUFRO World Series: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Volume 35, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tacconi, L. The Problem of Illegal Logging. In Illegal Logging: Law Enforcement, Livelihoods and the Timber Trade; Tacconi, L., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, A. Tackling Illegal Logging and the Related Trade. What Progress and Where Next? Chatham House: London, UK, 2015; 64p. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Rojo, J.M. Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico. Forests 2021, 12, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070838

Torres-Rojo JM. Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico. Forests. 2021; 12(7):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070838

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Rojo, Juan Manuel. 2021. "Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico" Forests 12, no. 7: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070838

APA StyleTorres-Rojo, J. M. (2021). Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico. Forests, 12(7), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070838