Professionals’ Feedback on the PEFC Fair Supply Chain Project Activated in Italy after the “Vaia” Windstorm

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Forest owners (including without PEFC certification) who possess timber, of any amount and type, from the areas subjected to the windstorm. They must: (i) have logging authorization based on the appropriate regional regulations, and (ii) communicate the size of each lot to be sold, which shall have a volume of less than 10,000 m3 of timber;

- First buyers include forest and processing enterprises, along with retailers. They are either PEFC CoC-certified, or if not, by adhering to the fair supply chain, they can benefit from favored economic conditions to obtain certification. First buyers are required to purchase timber from the areas subjected to the storm in amounts equal to at least 50% of their annual timber need or at least 10,000 m3. In any case, they shall not buy a single lot larger than 5000 m3;

- Italian companies of the wood sector must be PEFC CoC-certified and can use the PEFC fair supply chain label if (i) they purchase timber from suppliers involved in the fair supply chain, and (ii) they put the label on products consistent with the input material;

- Supporting organizations, such as commerce associations and forest consortia, can adhere freely. They are only required to promote the PEFC fair supply chain, for instance, by organizing workshops.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Frame and Questionnaire Development

2.2. Survey Implementation and Data Analysis

2.3. Study Limitations

3. Results

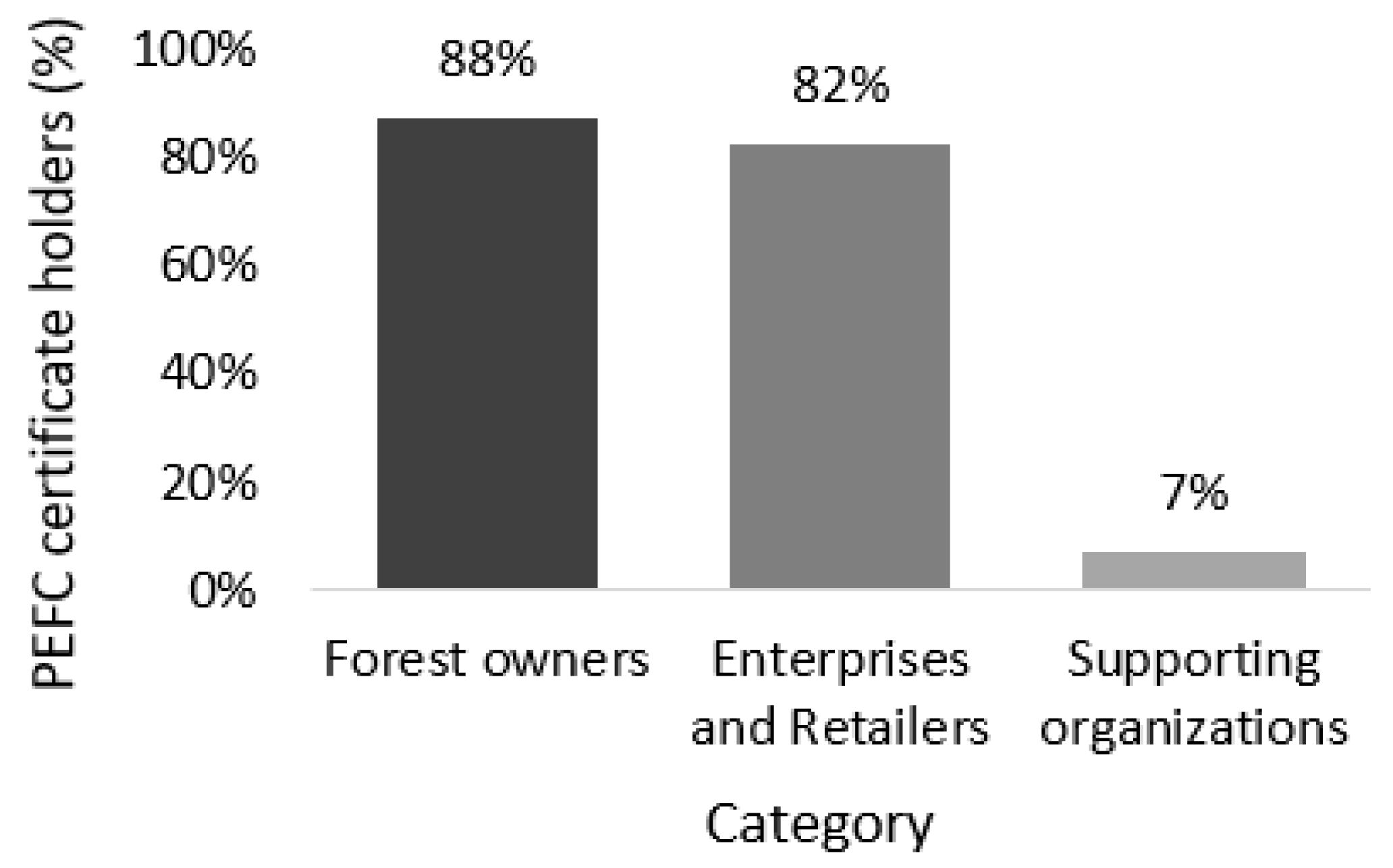

3.1. Description of Respondents

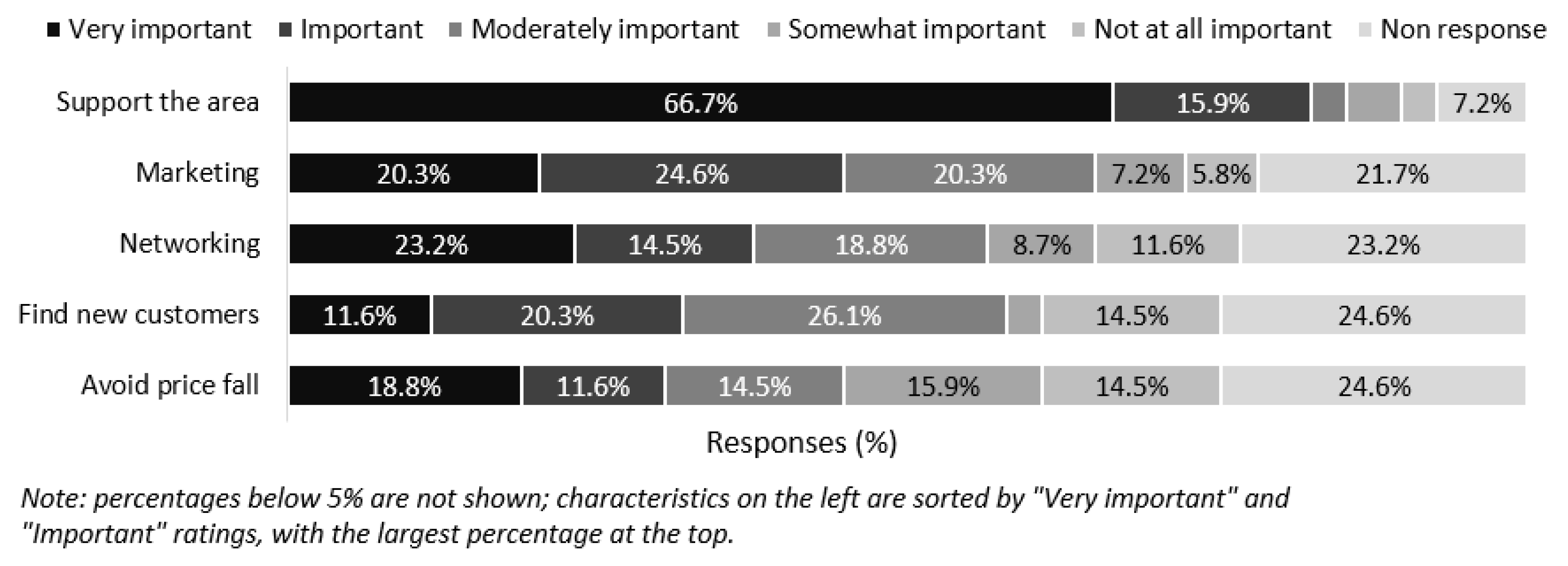

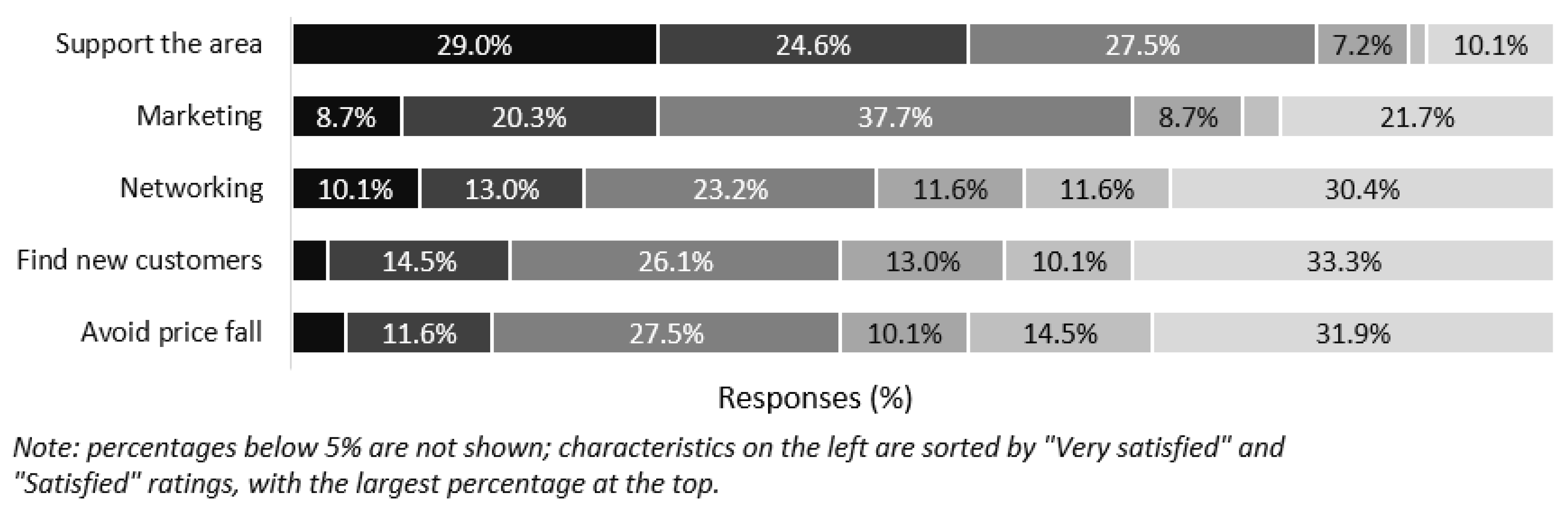

3.2. Reasons for Adhering and Satisfaction

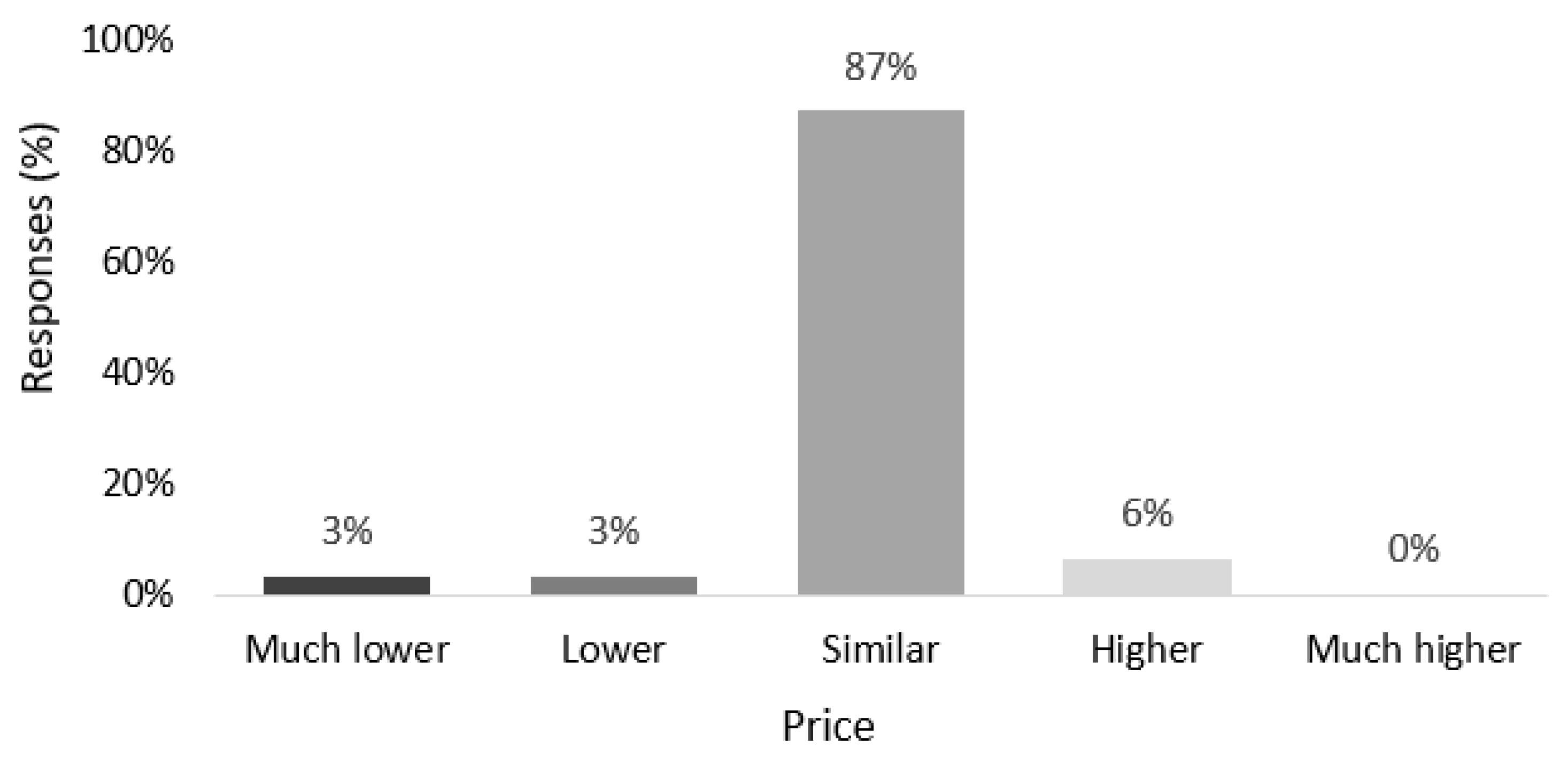

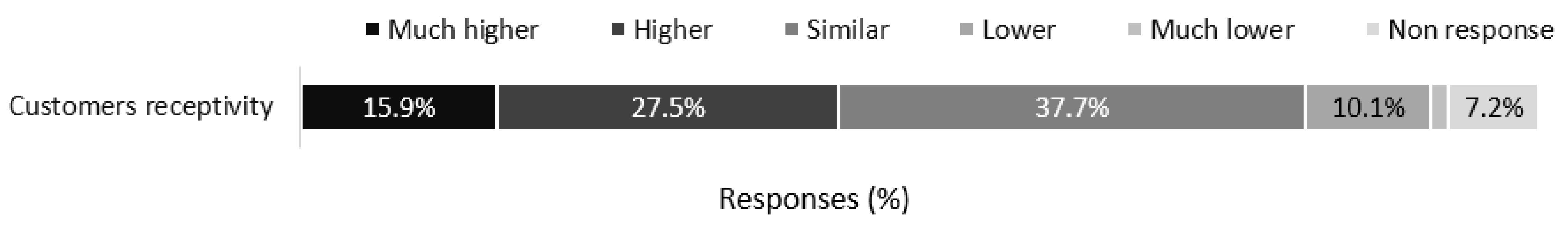

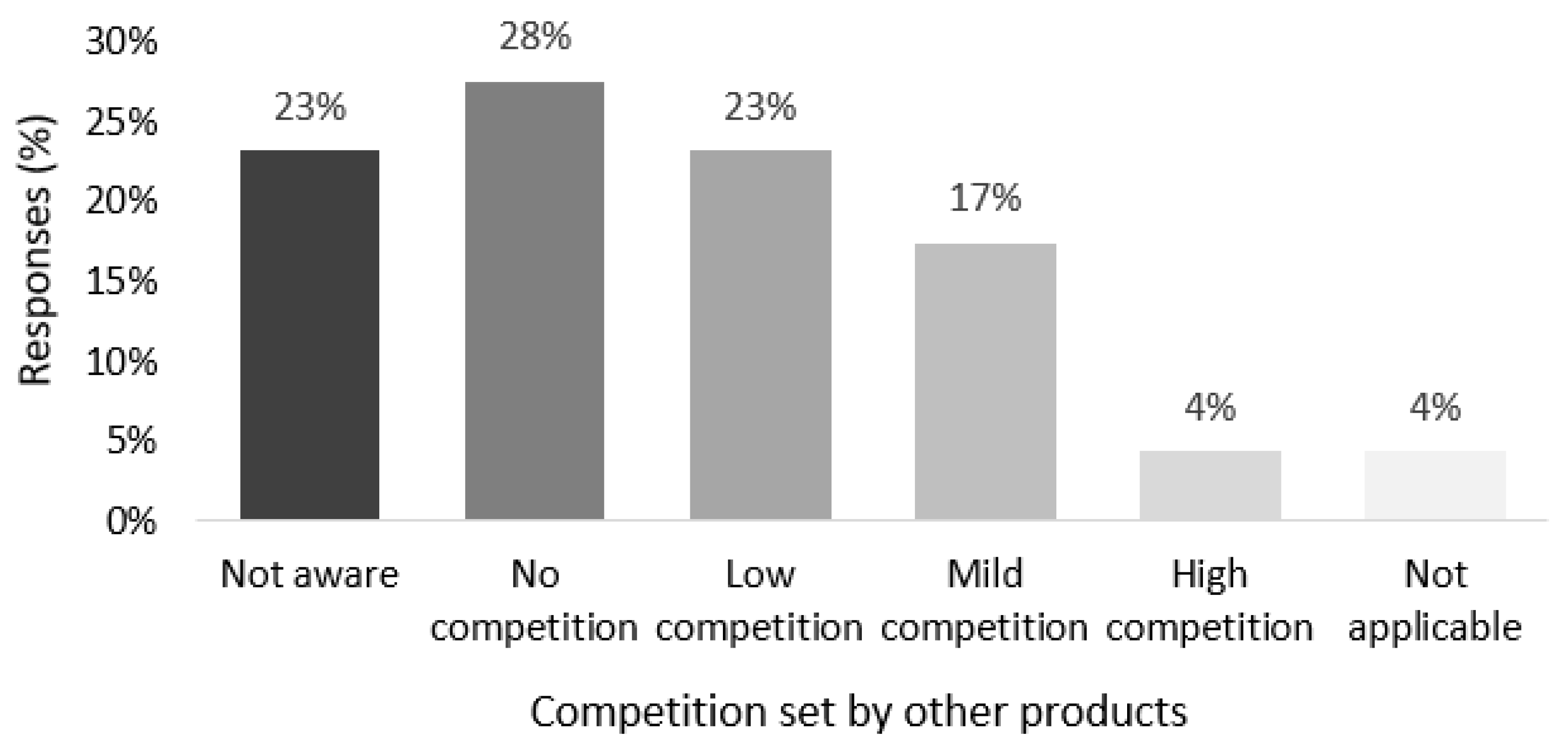

3.3. Selling of Labeled Material

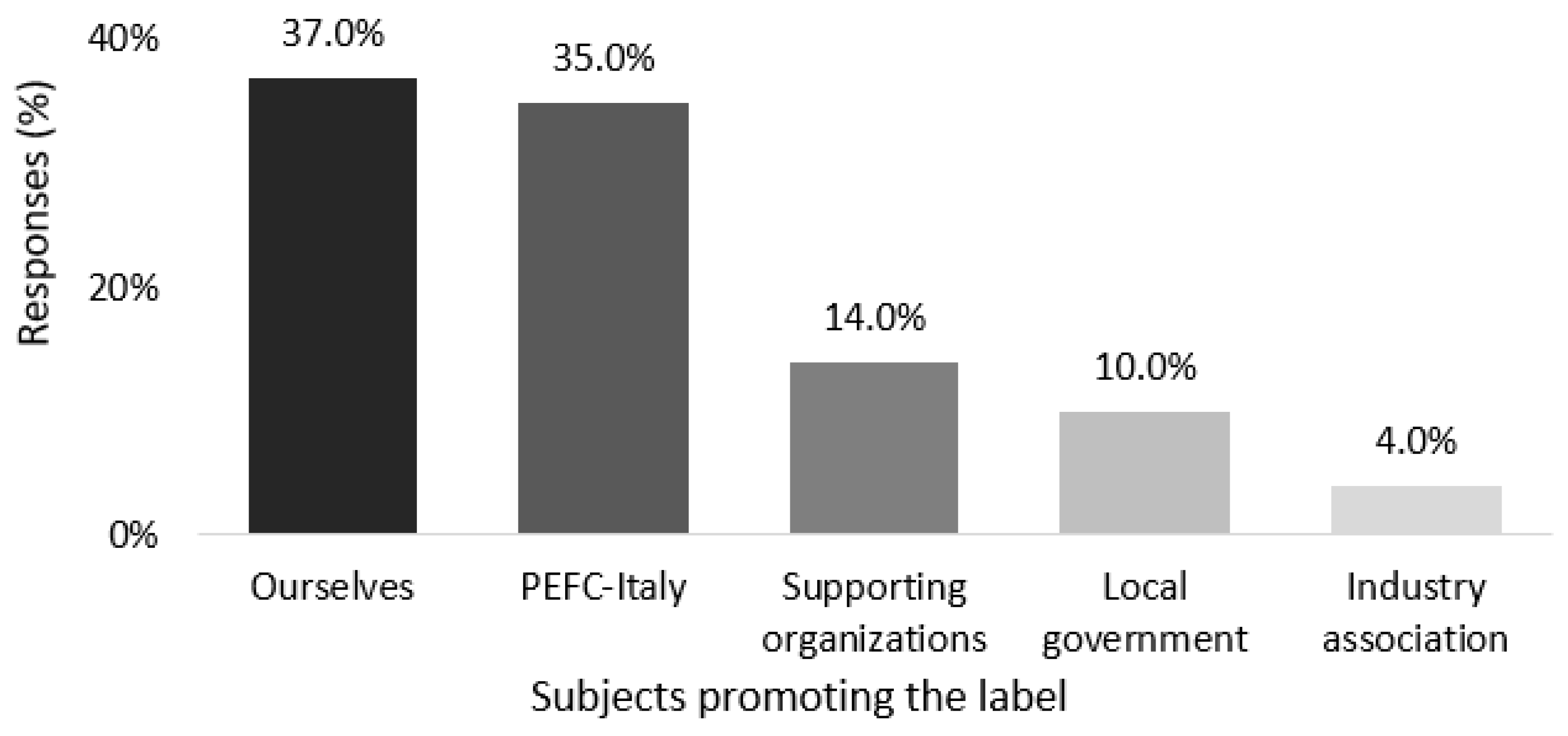

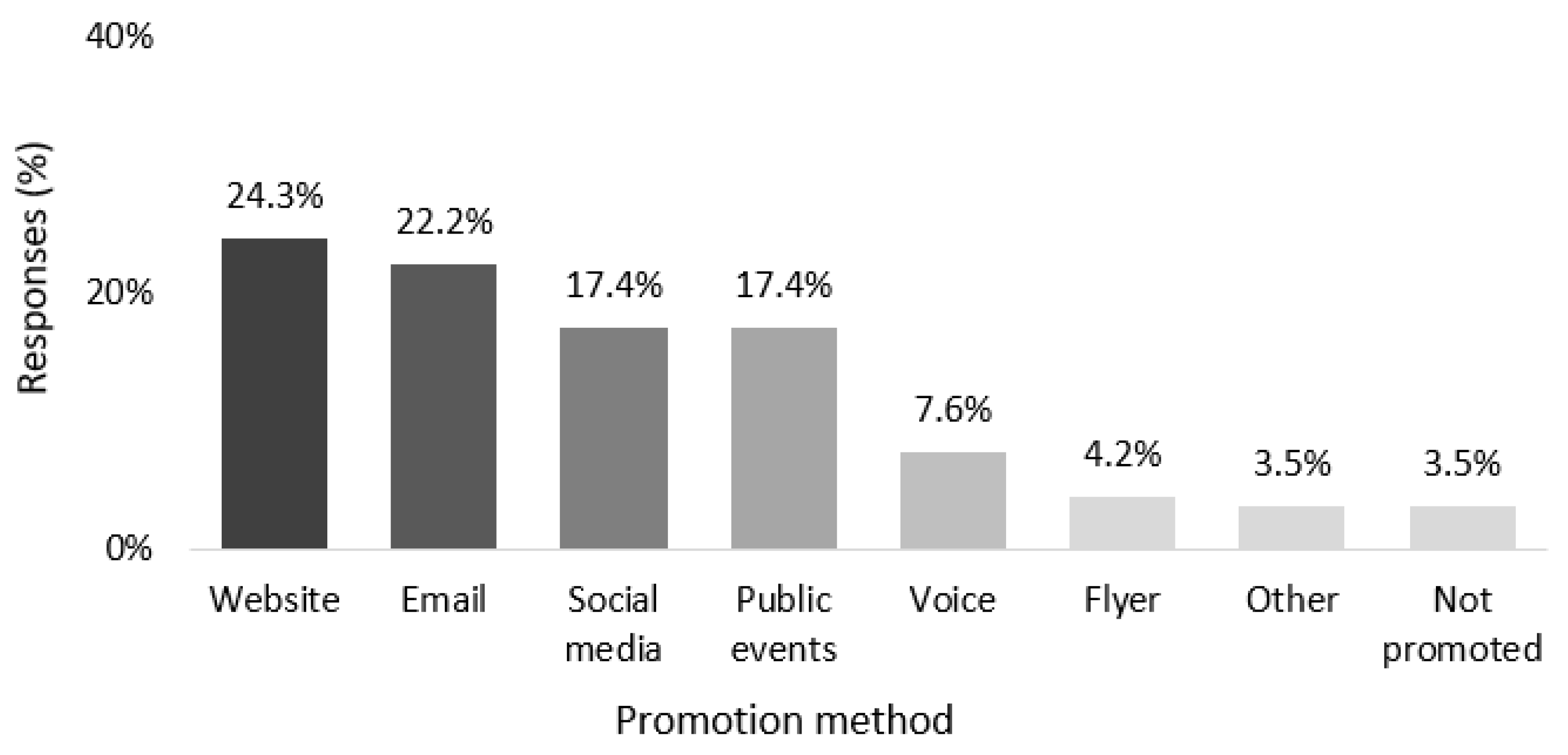

3.4. Promotion of the Label

4. Discussion

4.1. Description of Respondents, Reasons to Adhere, and Satisfaction

4.2. Sale of Labeled Materials and Promotions

4.3. Indications for Similar Systems to Be Activated in the Future

- The managing authority should place high importance on its communication efforts, which is key to create awareness, and communication and promotion should be consistent over time;

- The local-regional dimension should be treated as fundamental, even in the case of large disturbances affecting several regions;

- Creating networking and business opportunities is a relevant aspect that should be pursued by means of appropriate strategies;

- Specific initiatives should be addressed at forest owners, as the subjects most impacted by the disruptive event;

- Support to promote the system should be sought by public institutions, who should try to involve supporting organizations from the very beginning;

- The ethical image gained by adhering to the project and the increased attention of final customers should be used as relevant arguments to convince organizations to adhere;

- Promotions should aim at increasing the knowledge among professionals and customers of timber coming from forest disturbances: its quality is generally considered low, but this is not necessarily the case as the quality depends on several factors;

- Performing a survey among the adhering organizations sometime after the beginning of the project should be planned as a useful tool for continuous improvement.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | In which Italian regions or countries does you company usually sell? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Friuli Venezia Giulia ☐ Trentino-Alto Adige ☐ Veneto ☐ Lombardia ☐ Other northern regions ☐ Central Italy ☐ Southern Italy ☐ France ☐ Switzerland ☐ Austria ☐ Slovenia ☐ Other countries ☐ Not applicable to our enterprise/organization |

| 2 | What is the role of your enterprise/organization in the PEFC fair supply chain? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Forest owner ☐ Forest operation enterprise ☐ Processing enterprise ☐ Trader/retailer ☐ Supporting organization ☐ Other: |

| 3 | Why did you adhere to the PEFC fair supply chain? [rate from 1 (reason not important at all) to 5 (very important reason)] | |

| A | To avoid a price fall | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| For marketing purposes | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To enter a network of related enterprises | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To find new customers/markets | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To support the area after the storm | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Other: | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 3.1 | If in the previous question, you rated the “other” option, what are you referring to? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

| 4 | How much are you satisfied with the effectiveness of the label/initiative? [rate from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied)] If you had no expectation for a certain option, leave the field blank. | |

| A | To avoid a price fall | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| For marketing purposes | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To enter a network of related enterprises | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To find new customers/markets | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| To support the area after the storm | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Other: | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 5 | If you assigned 1 or 2 (very dissatisfied or dissatisfied) to certain options in the previous question, why are you not satisfied? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

| 6 | Did you receive any positive or negative feedback from your customers/commercial partners concerning the label/initiative? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

| 7 | How did you learn about the existence of the label/initiative, PEFC fair supply chain? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Press release ☐ PEFC communication ☐ Forest service ☐ Organizations (region, university, trade/industry association, etc.) ☐ A client who asked for it ☐ A colleague ☐ A friend ☐ Other: |

| 8 | Was your enterprise/organization a PEFC certificate holder before joining the PEFC fair supply chain? |

| A | ☐ Yes ☐ No |

| 9 | Which roundwood assortments did you label, or described in the invoice as labeled? (for each assortment, mark all species that apply: S = spruce and silver fir; B = beech; L = larch; P = pine) | ||||

| A | Single assortment, without any classification | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P |

| Short butt-logs | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Logs for beams | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| For packaging | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Poles | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Pulpwood | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Firewood | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| For chipping | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Not applicable to our enterprise/organization | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| 10 | Which sawn wood assortments/products did you label, or described in the invoice as labeled? (for each assortment/product, mark all species that apply: S = spruce and silver fir; B = beech; L = larch; P = pine) | ||||

| A | Beams including scantlings and laths | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P |

| Boards including small boards | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Poles | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Chips | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Firewood | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| End-product | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| Not applicable to our enterprise/organization | ☐ S | ☐ B | ☐ L | ☐ P | |

| 11 | How would you describe the sale price of your PEFC fair supply chain labeled products? |

| A | ☐ Much lower compared to our other similar products ☐ Lower compared to our other similar products ☐ Same price as for our other similar products ☐ Higher compared to our other similar products ☐ Much higher compared to our other similar products ☐ Not applicable to our organization |

| 12 | Who promoted the label? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Ourselves ☐ Our industry association ☐ The local government ☐ PEFC ☐ Supporting organizations that are part of the label ☐ Other: |

| 13 | How was the label promoted? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ By email ☐ By word-of-mouth ☐ By flyers ☐ At public events (fairs, congresses, etc.) ☐ By posting to our website or other websites ☐ By posting to our social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) ☐ Did not actively promote it ☐ Other: |

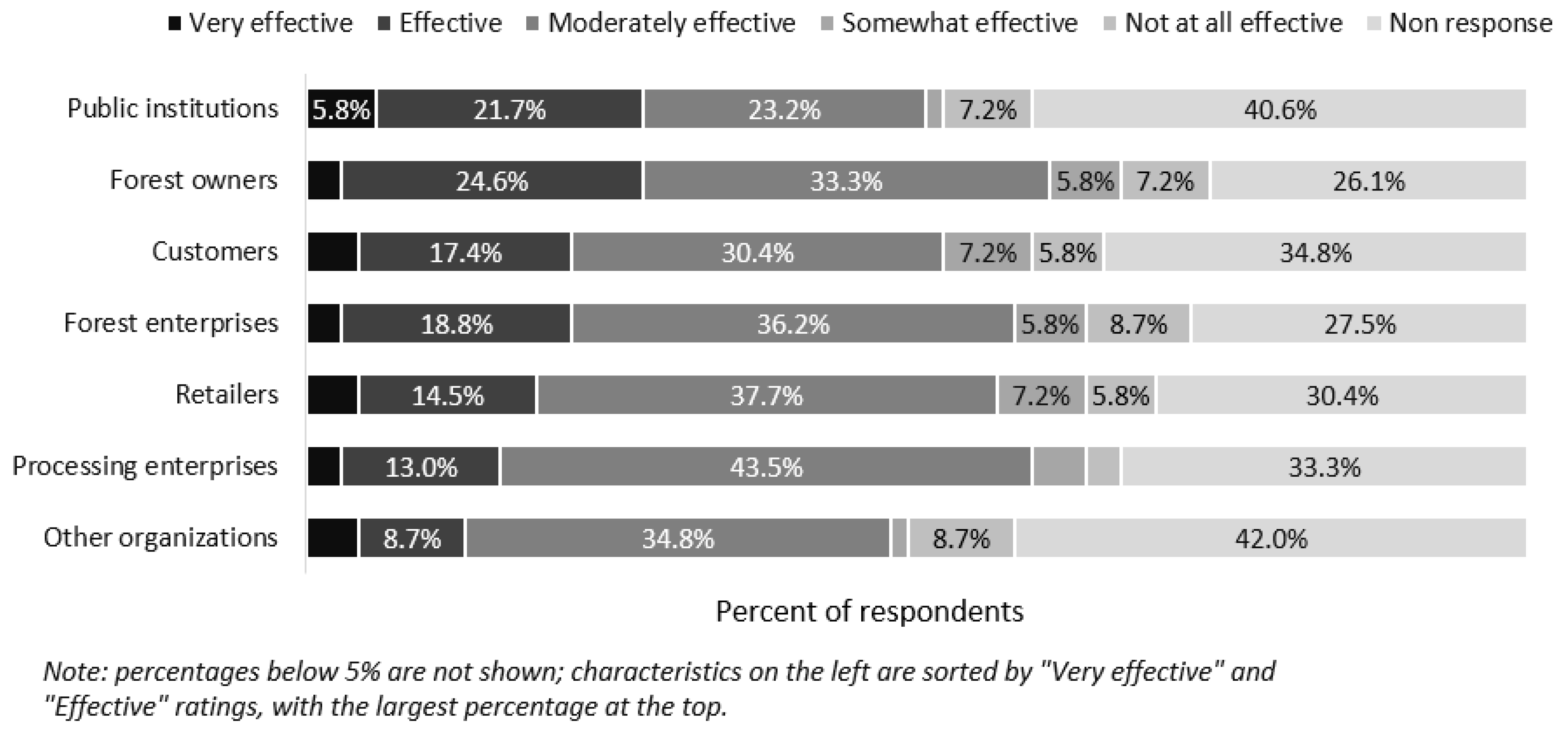

| 14 | Considering the effort you made, please rate the effectiveness of your promotional activity, in terms of the increased level of awareness of the subjects listed below. [from 1 (not effective at all) to 5 (highly effective), mark all categories to which your promotion was addressed] | |

| A | Forest owners | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Forest enterprises | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| First and second processing enterprises | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Traders/retailers | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Customers | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Public institutions | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Other institutions (trade/industry associations, etc.) | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 15 | If you assigned 1 or 2 (not effective at all or slightly effective) to some options in the previous question, why was the promotion not effective? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

| 16 | To which type of customer did you sell the labeled material? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Forest enterprises ☐ First and second processing enterprises ☐ Traders/retailers ☐ Customers ☐ Public institutions ☐ Other institutions (trade/industry associations, etc.) ☐ Not applicable to our enterprise/organization |

| 17 | Where are the subjects to whom you sold the labeled material located? (mark all that apply) |

| A | ☐ Friuli Venezia Giulia ☐ Trentino-Alto Adige ☐ Veneto ☐ Lombardia ☐ Other northern regions ☐ Central Italy ☐ Southern Italy ☐ France ☐ Switzerland ☐ Austria ☐ Slovenia ☐ Other countries ☐ Not applicable to our enterprise/organization |

| 18 | In your opinion, were customers in the regions affected by the storm more receptive to the label/initiative than customers in other regions? [from 1 (much less receptive) to 5 (very much more receptive)] |

| A | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 19 | What is your perception of how the label/initiative contributed to enhancing the following images of your company? [from 1 (did not contribute at all) to 5 (highly contributed)] | |

| A | Ethical image | 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Attentive to sustainability | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| Attentive to our country | 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 20 | On the market, there are semifinished products and end-products made of timber coming from the windstorm that are NOT labeled PEFC fair supply chain. Are you aware of them, and if you are, do you regard them as competition? |

| A | ☐ I am not aware of such other products ☐ I am aware of them and they are no competition ☐ I am aware of them and they are setting little competition ☐ I am aware of them and they are setting mild competition ☐ I am aware of them and they are setting high competition ☐ Not applicable to our enterprise/organization |

| 21 | In your opinion, which is the major obstacle to commercializing the timber coming from the Vaia storm? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

| 22 | Do you have any other thoughts or suggestions you want to share about the PEFC fair supply chain? |

| A | Open-ended answer |

References

- Giannetti, F.; Pecchi, M.; Travaglini, D.; Francini, S.; D’Amico, G.; Vangi, E.; Cocozza, C.; Chirici, G. Estimating VAIA windstorm damaged forest area in Italy using time series Sentinel-2 imagery and continuous change detection algorithms. Forests 2021, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, R.; Ascoli, D.; Corona, P.; Marchetti, M.; Vacchiano, G. Silviculture and wind damages. The storm “Vaia.”. Forest@-Rivista Selvic. Ecol. For. 2018, 15, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cadei, A.; Mologni, O.; Röser, D.; Cavalli, R.; Grigolato, S. Forwarder productivity in salvage logging operations in difficult terrain. Forests 2020, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Piano d’azione Vaia in Trentino. L’evento, gli interventi, i risultati. Sherwood 2020, 248 (Suppl. 2), 3–72. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.pefc.it/ (accessed on 4 July 2021).

- Maesano, M.; Ottaviano, M.; Lidestav, G.; Lasserre, B.; Matteucci, G.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Marchetti, M. Forest certification map of Europe. iForest 2018, 11, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernholz, K.; Bowyer, J.; Erickson, G.; Groot, H.; Jacobs, M.; McFarland, A.; Pepke, E. Forest Certification Update 2021: The Pace of Change. Available online: https://www.dovetailinc.org/portfoliodetail.php?id=60085a177dc07 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Geatti, P.; Novelli, V.; Marangon, F.; Troiano, S. The birth of a new sustainability label: “Filiera solidale PEFC—Vaia 2018—Insieme si può”. In AISME 2020, Salerno, Italy, 13–14 February 2020; Esposito, B., Malandrino, O., Sessa, M.R., Sica, D., Eds.; FrancoAngeli s.r.l.: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Negro, F.; Ascoli, D.; Garbarino, M.; Marzano, R. Impact of forest disturbances on wood quality: A review. In Renewable Resources for a Sustainable and Healthy Future, Proceedings of the 63rd International Convention of Society of Wood Science and Technology, Portorose, Slovenia (virtual conference), 12–15 July 2020; LeVan-Green, S., Ed.; SWST: Monona, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://filierasolidalepefc.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/disciplinare_filiera_solidale_pefc-1.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Pilli, R.; Vizzari, M.; Chirici, G. Combined effects of natural disturbances and management on forest carbon sequestration: The case of Vaia storm in Italy. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Ruda, A.; Kalasová, Ž.; Paletto, A. The forest stakeholders’ perception towards the NATURA 2000 network in the Czech Republic. Forests 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronholm, T.; Bengtsson, D.; Bergström, D. Family forest owners’ perception of management and thinning operations in young dense forests: A survey from Sweden. Forests 2020, 11, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamache, S.L.; Espinoza, O.; Aro, M. Professional consumer perceptions about thermally modified wood. Bioresources 2017, 12, 9487–9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, D. Chi-square test is statistically significant: Now what? Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2015, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgardner, M.; Montague, I.; Wiedenbeck, J. Survey response rates in the forest products literature from 2000 to 2015. Wood Fiber Sci. 2017, 49, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Michal, J.; Březina, D.; Šafařík, D.; Kupčák, V.; Sujová, A.; Fialová, J. Analysis of socioeconomic impacts of the FSC and PEFC certification systems on business entities and consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riedl, M.; Jarský, V.; Palátová, P.; Sloup, R. The challenges of the forestry sector communication based on an analysis of research studies in the Czech Republic. Forests 2019, 10, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zubizarreta, M.; Arana-Landín, G.; Cuadrado, J. Forest certification in Spain: Analysis of certification drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 294, 126267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, O.; Hämäläinen, K.; Häyrinen, L.; Berghäll, S.; Lähtinen, K.; Toppinen, A. Strategic business networks in the Finnish wood products industry: A case of two small and medium-sized enterprises. Silva Fennica 2016, 3, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franzini, F.; Lähtinen, K.; Nyrud, A.Q.; Widmark, C.; Hoen, H.F.; Toppinen, A. Citizen views on wood as a construction material: Results from seven European countries. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, A. PEFC certification in Italy, state of the art and customers recognition. In Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Silviculture, Firenze, Italy, 26–29 November 2014; Ciancio, O., Ed.; Accademia Italiana di Scienze Forestali: Firenze, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paluš, H.; Parobek, J.; Vlosky, R.P.; Motik, D.; Oblak, L.; Jošt, M.; Glavonjić, B.; Dudík, R.; Wanat, L. The status of chain-of-custody certification in the countries of Central and South Europe. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2018, 76, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Magalhães, J.; Song, W.; Lu, W.; Xiong, L.; Chang, W.-Y.; Sun, Y. Effect of forest certification on international trade in forest products. Forests 2020, 11, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Information Collected | Question Number and Content | Scale of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Registration data | Organization name, Respondent’s position, 1. Area of activity, 8. Already PEFC certificate holder | Open-ended questions |

| Activity within the PEFC fair supply chain | 2. Organization category, 9.–10. Type of labeling (roundwood/sawn wood/products), 12.–13. Label promotion methods, i.e., who and how, 16.–17. Sale of labeled material, i.e., customer type and location | None |

| Perceptions | 3.–3.1 Motivations for adherence, 4.–5. Satisfaction with label effectiveness, 6. Feedback received, 7. How the initiative was discovered, 11. Effect on sale price, 14.–15. Effectiveness of promotion, 18. Customer’s receptivity, 19. Label contribution to enhancing the organization’s image, 20. Competition from non-labeled material, 21. Major obstacle to commercializing, 22. Comments and suggestions | Likert importance scale (e.g., 1 = “not important at all”, 5 = “very important”) Likert scale of attribute content (e.g., 1 = “not contributed at all”, 5 = “highly contributed”) Open-ended questions |

| Goodness-of-Fit Test | Fischer’s Exact Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | χ2 | p-Value | χ2 | p-Value |

| Avoid price fall | 1.269 | 0.867 | 9.046 | 0.332 |

| Networking | 5.962 | 0.202 | 11.994 | 0.131 |

| Marketing | 12.852 | 0.012 | 10.607 | 0.184 |

| Find new customers | 14.154 | 0.007 | 7.192 | 0.511 |

| Support the area | 112.094 | <0.001 | 18.826 | 0.001 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Test | Fischer’s Exact Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | χ2 | p-Value | χ2 | p-Value |

| Avoid price fall | 15.021 | 0.005 | 10.948 | 0.156 |

| Networking | 5.542 | 0.236 | 15.224 | 0.035 |

| Marketing | 33.778 | <0.001 | 7.404 | 0.487 |

| Find new customers | 14.652 | 0.005 | 6.542 | 0.607 |

| Support the area | 24.774 | <0.001 | 14.777 | 0.031 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Test | Fischer Exact Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Enhancement | χ2 | p-Value | χ2 | p-Value |

| Ethical image | 14.471 | 0.002 | 14.620 | 0.014 |

| Attentive to sustainability | 32.636 | <0.001 | 20.029 | 0.002 |

| Attentive to our country | 11.723 | 0.019 | 16.451 | 0.021 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Test | Fischer’s Exact Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | χ2 | p-Value | χ2 | p-Value |

| Public institutions | 33.608 | <0.001 | 12.146 | 0.070 |

| Forest owners | 35.000 | <0.001 | 11.703 | 0.091 |

| Customers | 62.478 | <0.001 | 4.960 | 0.869 |

| Forest enterprises | 38.042 | <0.001 | 6.408 | 0.630 |

| Retailers | 22.556 | <0.001 | 9.021 | 0.295 |

| Processing enterprises | 22.780 | <0.001 | 12.486 | 0.063 |

| Other organizations | 42.250 | <0.001 | 10.004 | 0.165 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negro, F.; Espinoza, O.; Brunori, A.; Cremonini, C.; Zanuttini, R. Professionals’ Feedback on the PEFC Fair Supply Chain Project Activated in Italy after the “Vaia” Windstorm. Forests 2021, 12, 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070946

Negro F, Espinoza O, Brunori A, Cremonini C, Zanuttini R. Professionals’ Feedback on the PEFC Fair Supply Chain Project Activated in Italy after the “Vaia” Windstorm. Forests. 2021; 12(7):946. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070946

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegro, Francesco, Omar Espinoza, Antonio Brunori, Corrado Cremonini, and Roberto Zanuttini. 2021. "Professionals’ Feedback on the PEFC Fair Supply Chain Project Activated in Italy after the “Vaia” Windstorm" Forests 12, no. 7: 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070946

APA StyleNegro, F., Espinoza, O., Brunori, A., Cremonini, C., & Zanuttini, R. (2021). Professionals’ Feedback on the PEFC Fair Supply Chain Project Activated in Italy after the “Vaia” Windstorm. Forests, 12(7), 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12070946