Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historical Overview

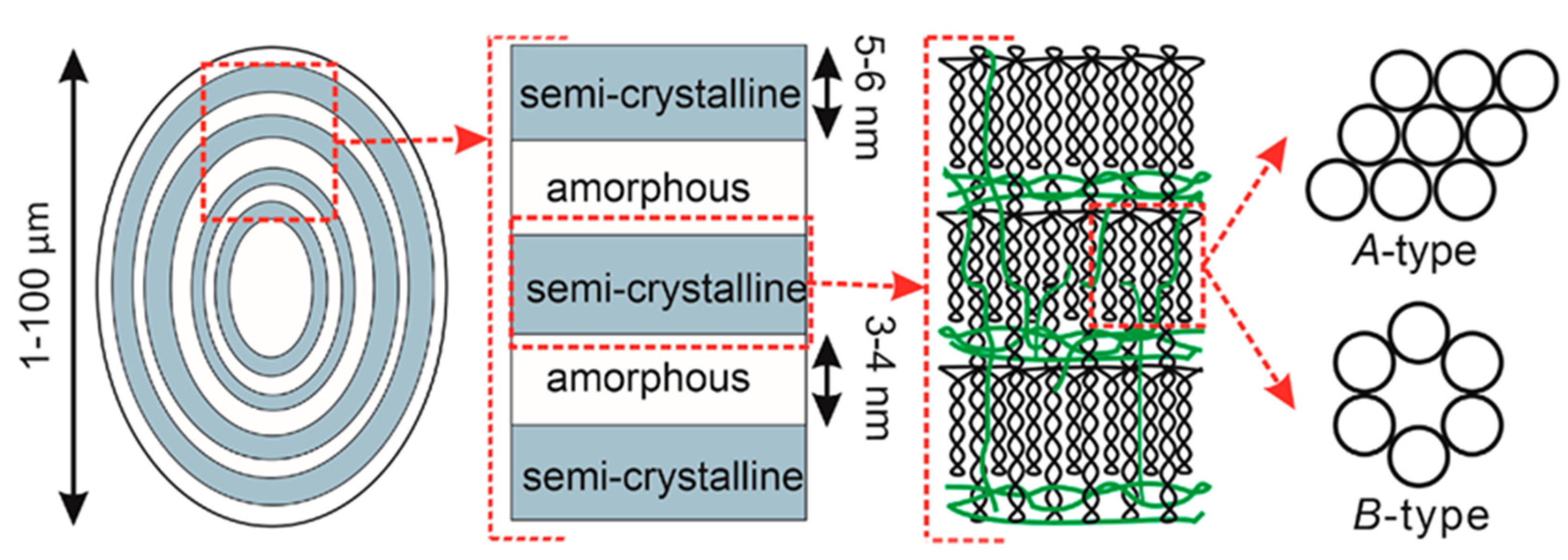

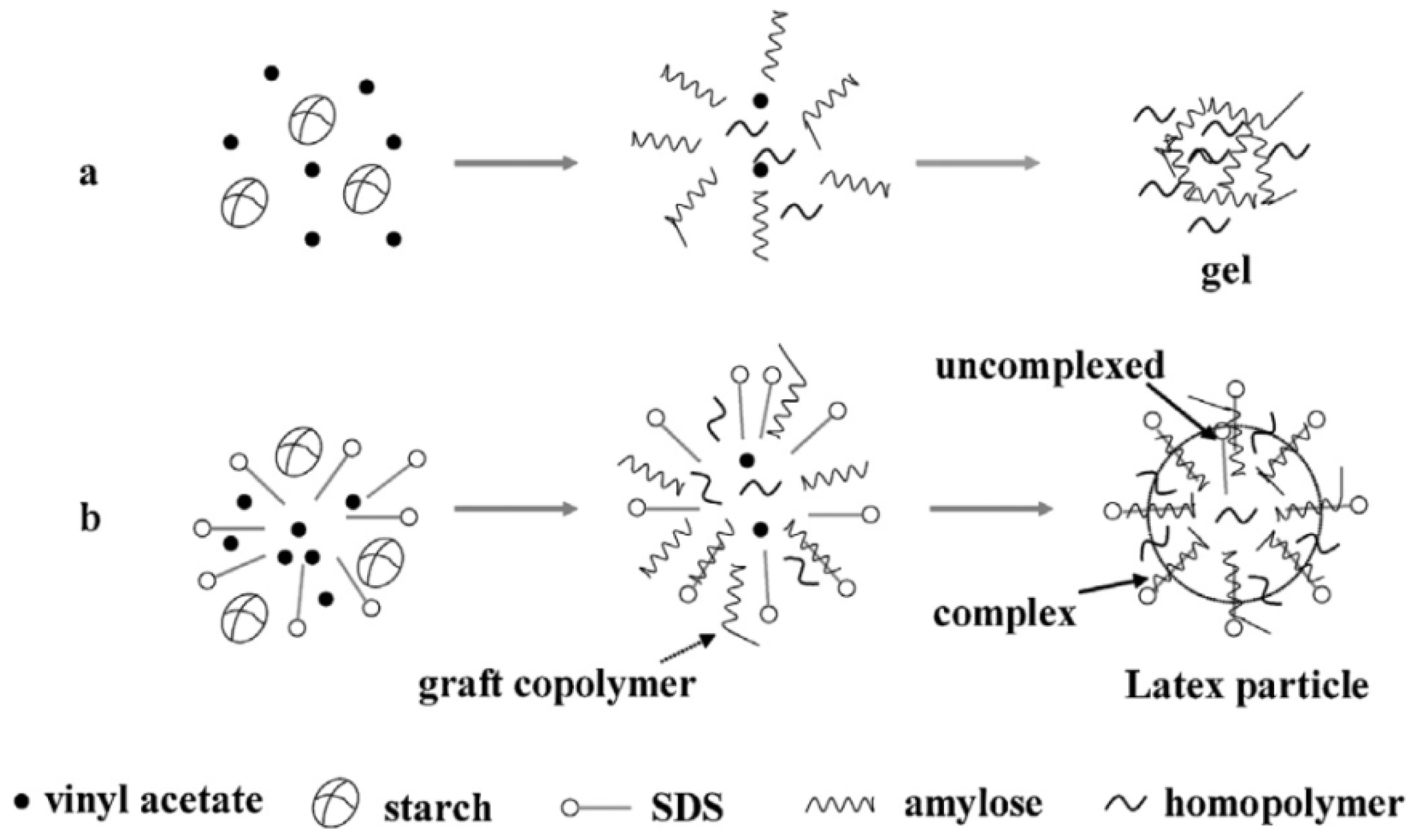

3. Sources of Starch

4. Starch-Based Wood Adhesives

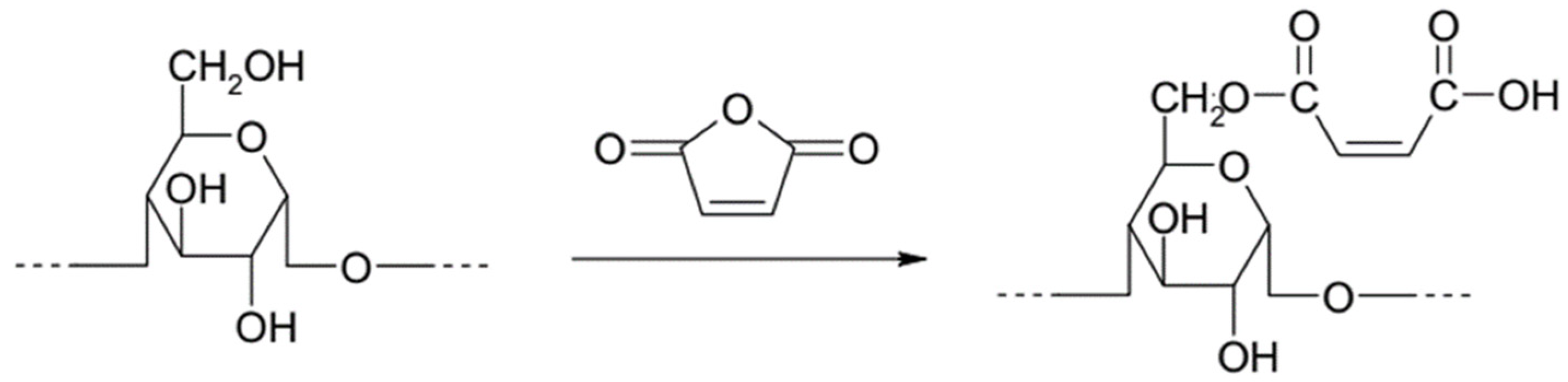

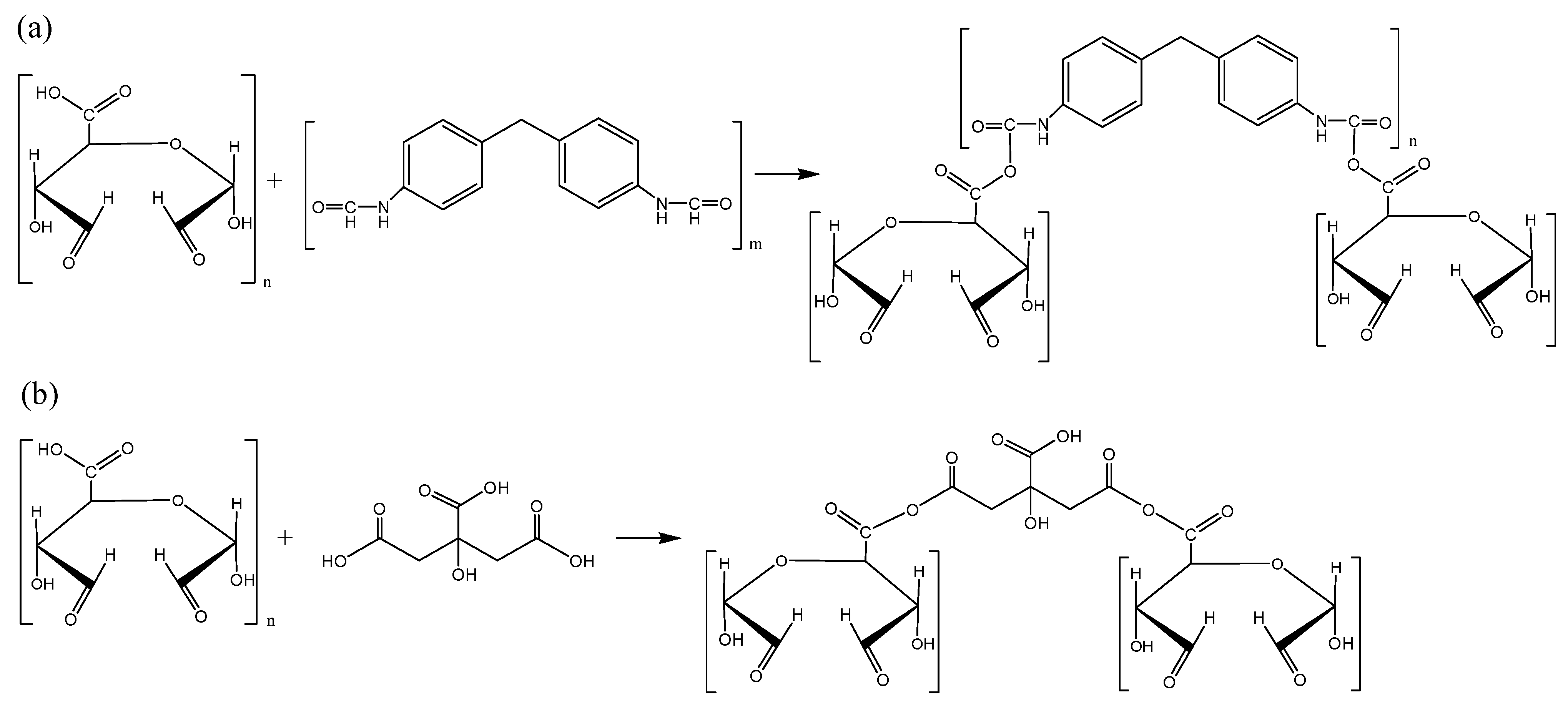

4.1. Chemical Treatments

| Treatment | Strength (MPa) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acid hydrolysis Dissolved in hydrochloric acid (HCI) and stirred at 60 °C (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 h) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—1.21 MPa (0 h) to 6.65 MPa (2 h) Wet state (23 °C)—0.8 MPa (0 h) to 3.6 MPa (2 h) | [66] |

| Silane coupling agent γ-Methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (KH570) (0%–10%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—5.5 MPa (0%) to 6.7 MPa (6%) Wet state (30 °C)—2.2 MPa (0%) to 2.6 MPa (4%) | [84] |

| Oxidation Hydrogen peroxide (3%–15%) olefin monomer (0%–5%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—4.43 MPa (3%) to 7.88 MPa (9%) Wet state (30 °C)—0.76 MPa (3%) to 4.09 MPa (9%) Dry state—3.28 MPa (0%) to 7.30 MPa (3%) Wet state (30 °C)—1.40 MPa (0%) to 4.22 MPa (3%) | [85,86] |

| Heat pretreatment 70, 80, and 90 °C | Tensile shear strength Dry state—8.63 MPa (control) to 10.17 MPa (90 °C) | [87] |

| Silica nanoparticles (0%–10%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—3.41 MPa (1%) to 5.12 MPa (10%) Wet state (23 °C)—1.62 MPa (1%) to 2.98 MPa (10%) | [88] |

| Montmorillonite (MMT, 0%–9%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—5.60 MPa (0%) to 10.60 MPa (5%) Wet state (23 °C)—1.7 MPa (0%) to 3.9 MPa (3%) | [89] |

| Anionic surfactant—Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 0%–2%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—5.5 MPa (2%) to 6.3 MPa (0%) | [76] |

| Esterification and polyisocyanate pre-polymer crosslinking(0%–20% prepolymer) | Block shear strength Dry state—2.3 MPa (0%) to ~12.0 MPa (10%) Wet state (30 °C) ~0 MPa (0%) to 4.0 MPa (10%) | [13] |

| Esterification with dodecenyl succinic anhydride (DDSA, 0%–8%) | Tensile shear strength Dry state—1.51 MPa (0%) to 2.61 MPa (2%) Wet state (63 °C)—0.58 MPa (0%) to 1.0 MPa (6%) | [78] |

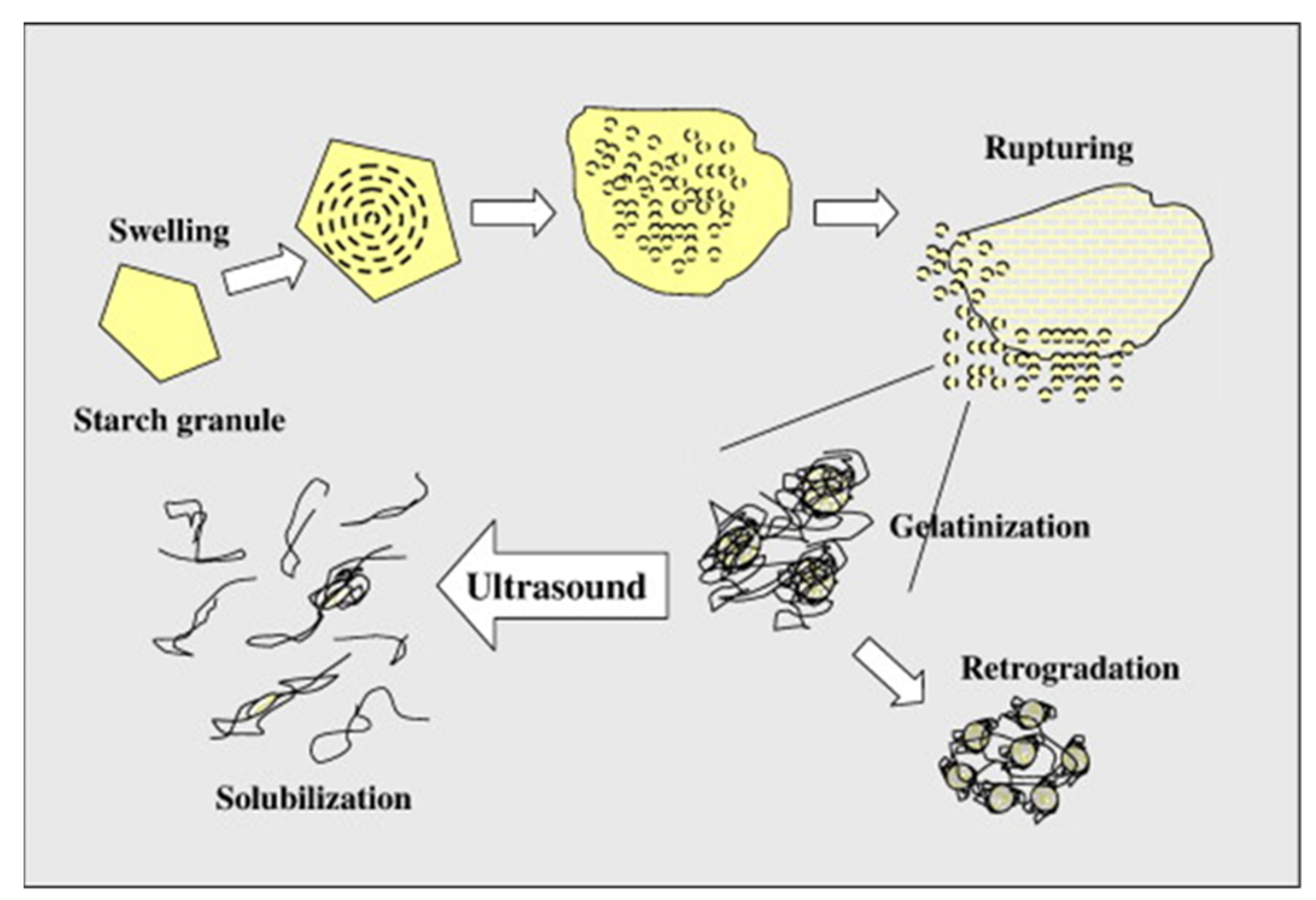

4.2. Physical Treatments

4.3. Enzymatic Treatments

5. Starch-Bonded Wood-Based Composites

5.1. Plywood

5.2. Particleboard

5.3. Medium-Density Fiberboard (MDF)

5.4. Laminated Veneer Lumber

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Din, Z.U.; Chen, L.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Z.; Ullah, I.; Lei, W.; Shi, D.; Alam, M.; Ullah, H.; Khan, S.A. Starch: An Undisputed Potential Candidate and Sustainable Resource for the Development of Wood Adhesive. Starch/Staerke 2020, 72, 1900276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharakitti, J.; Win, E.E.; Nimnuan, J.; Smith, S.M. Modified Starch-Based Adhesives: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Yadav, S.M.; Park, B.D. Modification of Oxidized Starch Polymer with Nanoclay for Enhanced Adhesion and Free Formaldehyde Emission of Plywood. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 2993–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmayr, R.; Šernek, M.; Myna, R.; Reichenbach, S.; Kromoser, B.; Liebner, F.; Wimmer, R. Heat bonding of wood with starch-lignin mixtures creates new recycling opportunities. Mater. Today Sustain. 2022, 19, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindlav-Westling, Å.; Gatenholm, P. Surface Composition and Morphology of Starch, Amylose, and Amylopectin Films. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, R.F.; Karkalas, J.; Qi, X. Starch-Composition, fine structure and architecture. J. Cereal Sci. 2004, 39, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buléon, A.; Colonna, P.; Planchot, V.; Ball, S. Starch granules: Structure and biosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1998, 23, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, Y.; Picchioni, F. Modification of starch: A review on the application of “green” solvents and controlled functionalization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dome, K.; Podgorbunskikh, E.; Bychkov, A.; Lomovsky, O. Changes in the crystallinity degree of starch having different types of crystal structure after mechanical pretreatment. Polymers 2020, 12, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J. Synthesis and Computer Simulation Analysis of MF Modified Starch Adhesive. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1992, 022171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsuk, P.; Sukolrat, A.; Kaewtatip, K.; Chantarak, S.; Kelarakis, A.; Chaibundit, C. Modified cassava starch/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend films plasticized by glycerol: Structure and properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S. Influence of Oxidized Starch and Modified Nano-SiO on Performance of Urea-FOrmaldehyde (UF) Resin. Polymers 2017, 41, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Gu, J.; Lv, S.; Cao, J.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and properties of normal temperature cured starch-based wood adhesive. BioResources 2016, 11, 4839–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Q.; Wen, J.; Wang, Z. Preparation and properties of cassava starch-based wood adhesives. BioResources 2016, 11, 6756–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.N.; Rahman, F.; Das, A.K.; Hiziroglu, S. An overview of different types and potential of bio-based adhesives used for wood products. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 112, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whistler, R.L.; Bemiller, J.N.; Paschall, E. Starch: Chemistry and Technology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1984; ISBN 0127462708. [Google Scholar]

- Radley, J.A. Adhesives from Starch and Dextrin. In Industrial Uses of Starch and Its Derivatives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1976; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Onusseit, H. Starch in industrial adhesives: New developments. Ind. Crops Prod. 1993, 1, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuwei, Y.; Bingjian, Z.; Qinglin, M. Study of Sticky Rice-Lime Mortar Technology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, C.M.; Co-investigator, N.; Lewandowski, C.M. Starch Chemistry and Technology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Ačkar, D.; Babić, J.; Jozinović, A.; Miličević, B.; Jokić, S.; Miličević, R.; Rajič, M.; Šubarić, D. Starch modification by organic acids and their derivatives: A review. Molecules 2015, 20, 19554–19570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutenberg, M.W.; Solarek, D. Starch derivatives: Production and uses. In Starch: Chemistry and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 311–388. [Google Scholar]

- Shogren, R.L. Starch: Properties and Materials Applications. In Biopolymers from Renewable Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Outlook-Biannual Report on Global Food Markets-November 2018; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 3906570541. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer, W.R. Methods in the Starch and Dextrose Industry. Anal. Chem. 1952, 24, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, S.W.; Lynch, K.M.; Arendt, E.K. Starch characteristics linked to gluten-free products. Foods 2017, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, R.P.; Cochrane, M.P.; Dale, M.F.B.; Duþus, C.M.; Lynn, A.; Morrison, I.M.; Prentice, R.D.M.; Swanston, J.S.; Tiller, S. A Starch Production and Industrial Use. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; He, C. Study on the rheological property of Cassava starch adhesives. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 6, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangseethong, K.; Lertpanit, S. Hypochlorite oxidation of cassava starch. Starch-Stärke 2005, 58, 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Iamareerat, B.; Singh, M.; Sadiq, M.B.; Anal, A.K. Reinforced cassava starch based edible film incorporated with essential oil and sodium bentonite nanoclay as food packaging material. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangseethong, K.; Termvejsayanon, N.; Sriroth, K. Characterization of physicochemical properties of hypochlorite- and peroxide-oxidized cassava starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Halal, S.L.M.; Bruni, G.P.; do Evangelho, J.A.; Biduski, B.; Silva, F.T.; Dias, A.R.G.; da Rosa Zavareze, E.; de Mello Luvielmo, M. The properties of potato and cassava starch films combined with cellulose fibers and/or nanoclay. Starch-Stärke 2018, 70, 1700115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.X.; Lin, Q.L.; Liu, G.Q.; Yu, F.X. A comparative study of the characteristics of cross-linked, oxidized and dual-modified rice starches. Molecules 2012, 17, 10946–10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lian, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, K.; Li, L. The retrogradation properties of glutinous rice and buckwheat starches as observed with FT-IR, 13C NMR and DSC. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Borght, A.; Goesaert, H.; Veraverbeke, W.S.; Delcour, J.A. Fractionation of wheat and wheat flour into starch and gluten: Overview of the main processes and the factors involved. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 41, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z. Bio-Based Wood Adhesives; He, Z., Ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781498740746. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, L. Starch and Protein Based Wood Adhesives. Degree Project in Polymer Technology, Nacka, Sweden, 2011. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:412056/FULLTEXT02.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Iida, Y.; Tuziuti, T.; Yasui, K.; Towata, A.; Kozuka, T. Control of viscosity in starch and polysaccharide solutions with ultrasound after gelatinization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Copeland, L.; Niu, Q.; Wang, S. Starch Retrogradation: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.T. Development of a Simplified Process for Obtaining Starch from Grain Sorghum. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Technological College, Lubbock, TX, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Radley, J.A. Industrial Uses of Starch and Its Derivatives, 1st ed.; Applied Science Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 1976; ISBN 9789401013314. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzyk, S.; Fortuna, T.; Juszczak, L.; Gałkowska, D.; Baczkowicz, M.; Łabanowska, M.; Kurdziel, M. Influence of amylose content and oxidation level of potato starch on acetylation, granule structure and radicals’ formation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 16, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadhave, R.V.; Mahanwar, P.A.; Gadekar, P.T. Starch-Based Adhesives for Wood/Wood Composite Bonding: Review. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2017, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antov, P.; Savov, V.; Neykov, N. Sustainable bio-based adhesives for eco-friendly wood composites a review. Wood Res. 2020, 65, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, R.; Bawon, P.; Lee, S.H.; Salim, S.; Lum, W.C.; Al-Edrus, S.S.O.; Ibrahim, Z. Properties of Particleboard from Oil Palm Biomasses Bonded with Citric Acid and Tapioca Starch. Polymers 2021, 13, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, U.; Naqash, F.; Gani, A.; Masoodi, F.A. Art and Science behind Modified Starch Edible Films and Coatings: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanier, N.L.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Dias, A.R.G.; da Rosa Zavareze, E. Molecular structure, functionality and applications of oxidized starches: A review. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1546–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Shi, R.; Yi, Z.; Shi, S.Q.; Gao, Q.; Li, J. A high-performance soybean meal-based plywood adhesive prepared via an ultrasonic process and using significantly lower amounts of chemical additives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Bartolome, M.; Schwaiger, N.; Flicker, R.; Seidl, B.; Kozich, M.; Nyanhongo, G.S.; Guebitz, G.M. Enzymatic synthesis of wet-resistant lignosulfonate-starch adhesives. New Biotechnol. 2022, 69, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A. The Use of Lignin in Pressure Sensitive Adhesives and Starch-Based Adhesives. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.S.; Ferreira, M.S.; Magalhães, M.T.; Bispo, A.P.G.; Oliveira, J.C.; Silva, J.B.A.; José, N.M. Starch-based Films Plasticized with Glycerol and Lignin from Piassava Fiber Reinforced with Nanocrystals from Eucalyptus. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, E.; Rao, J.; Lin, Q.; Fan, M.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, N. Improved wet shear strength in eco-friendly starch-cellulosic adhesives for woody composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weakley, F.B.; Carr, M.E.; Mehltretter, C.L. Dialdehyde Starch in Paper Coatings Containing Soy Flour-Isolated Soy Protein Adhesive. Starch-Stärke 1972, 24, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubarik, A.; Pizzi, A.; Allal, A.; Charrier, F.; Khoukh, A.; Charrier, B. Cornstarch-mimosa tannin-urea formaldehyde resins as adhesives in the particleboard production. Starch/Staerke 2010, 62, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, S.; Kızılcan, N.; Bengü, B. Development of bio-based cornstarch-Mimosa tannin-sugar adhesive for interior particleboard production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Park, B.D.; Hong, M.K. Tuning of adhesion and disintegration of oxidized starch adhesives for the recycling of medium density fiberboard. BioResources 2020, 15, 5156–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Park, B.; Kim, Y.; Yun, J.; Shin, H.C. Visual inspection of surface mold growth on medium-density fiberboard bonded with oxidized starch adhesives. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Park, B.; Hong, M. Tailoring of oxidized starch’s adhesion using crosslinker and adhesion promotor for the recycling of fiberboards. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Gu, J.; Lv, S.; Cao, J.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and properties of isocyanate prepolymer/corn starch adhesive. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Md Tahir, P.; Lum, W.C.; Tan, L.P.; Bawon, P.; Park, B.-D.; Osman Al Edrus, S.S.; Abdullah, U.H. A Review on Citric Acid as Green Modifying Agent and Binder for Wood. Polymers 2020, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, X. Preparation of the plywood using starch-based adhesives modified with blocked isocyanates. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valodkar, M.; Thakore, S. Isocyanate crosslinked reactive starch nanoparticles for thermo-responsive conducting applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2010, 345, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Peng, Y. Isocyanate-functionalized starch as biorenewable backbone for the preparation and application of poly(ethylene imine) grafted starch. Mon. Chem.-Chem. Mon. 2017, 148, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdosian, F.; Pan, Z.; Gao, G.; Zhao, B. Bio-Based Adhesives and Evaluation for Wood Composites Application. Polymers 2017, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chi, J.; Cheng, S. Starch and its derivatives for paper coatings: A review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 135, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L. Effects of different durations of acid hydrolysis on the properties of starch-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Fang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z. Effect of HCl on Starch Structure and Properties of Starch-based Wood Adhesives. BioResources 2016, 11, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Lv, S.; Gu, J.; Tan, H.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y. Influence of acid hydrolysis on properties of maize starch adhesive. Pigment Resin Technol. 2017, 46, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, R.V.; Sheety, P.; Mahanwar, P.A.; Gadekar, P.T.; Desai, B.J. Silane Modification of Starch-Based Wood Adhesive: Review. Open J. Polym. Chem. 2019, 09, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Gu, J.; Tan, H.; Zhu, L. Preparation and properties of a starch-based wood adhesive with high bonding strength and water resistance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Huang, J.; Ge, Z.; Guo, J.; Feng, X.; Xu, Q. Improvement of the bonding properties of cassava starch-based wood adhesives by using different types of acrylic ester. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-W.; Li, F.-Y.; Li, J.-F.; Xie, Q.; Xu, J.; Guo, A.-F.; Wang, C.-Z. Effect of Crystal Structure and Hydrogen Bond of Thermoplastic Oxidized Starch on Manufacturing of Starch-Based Biomass Composite. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 5, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Bastida, C.A.; Tapia-Blácido, D.R.; Méndez-Montealvo, G.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Velázquez, G.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J. Effect of amylose content and nanoclay incorporation order in physicochemical properties of starch/montmorillonite composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotal, M.; Bhowmick, A.K. Polymer nanocomposites from modified clays: Recent advances and challenges. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 51, 127–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tudor, E.M.; Scheriau, C.; Barbu, M.C.; Réh, R.; Krišťák, Ľ.; Schnabel, T. Enhanced Resistance to Fire of the Bark-Based Panels Bonded with Clay. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, L.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Kowalczyk, A. Improving the performance of starch-based wood adhesive by using sodium dodecyl sulfate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 99, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Lin, Q.; Rao, J.; Zeng, Q. Water resistances and bonding strengths of soy-based adhesives containing different carbohydrates. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gu, J.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, P. Physicochemical properties of starch adhesives enhanced by esterification modification with dodecenyl succinic anhydride. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait, A.; Boussetta, A.; Kassab, Z.; Nadifiyine, M. Elaboration of carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals filled starch-based adhesives for the manufacturing of eco-friendly particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 348, 128683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhuang, B.; Wang, X.A.; Wu, Z.; Wei, W.; Aladejana, J.T.; Hou, X.; Yves, K.G.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J. Chitosan used as a specific coupling agent to modify starch in preparation of adhesive film. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.; Widyorini, R.; Prayitno, T.A.; Sulistyo, J. Bonding performance of maltodextrin and citric acid for particleboard made from nipa fronds. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 45, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Ali, S.Z.; Somashekar, R.; Mukherjee, P.S. Nature of crystallinity in native and acid modified starches. Int. J. Food Prop. 2006, 9, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masina, N.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; du Toit, L.C.; Govender, M.; Indermun, S.; Pillay, V. A review of the chemical modification techniques of starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zia-ud-Din; Fei, P.; Jin, W.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Z. Enhancing the performance of starch-based wood adhesive by silane coupling agent(KH570). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Wang, X.L.; Zhao, G.M.; Wang, Y.Z. Influence of oxidized starch on the properties of thermoplastic starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.D.; Zhang, Y.R.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, Y.Z. High carbonyl content oxidized starch prepared by hydrogen peroxide and its thermoplastic application. Starch/Staerke 2009, 61, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Cheng, L.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Effects of heat pretreatment of starch on graft copolymerization reaction and performance of resulting starch-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z. Bonding strength and water resistance of starch-based wood adhesive improved by silica nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Hong, Y. Effects of montmorillonite addition on the performance of starch-based wood adhesive. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parovuori, P.; Hamunen, A.; Forssell, P.; Autio, K.; Poutanen, K. Oxidation of Potato Starch by Hydrogen Peroxide. Starch-Stärke 1995, 47, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, P.; Sorokin, A.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Murzin, D.Y.; Salmi, T. Oxidation of starch by H2O2 in the presence of iron tetrasulfophthalocyanine catalyst: The Effect of catalyst concentration, pH, solid-liquid ratio, and origin of starch. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 9351–9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.E.; Gupta, S.K.; Johnson, J. Oxidation of Starch by Hydrogen Peroxide in the Presence of UV Light-Part. I. Starch-Stärke 1971, 23, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, S.; Kızılcan, N.; Bengu, B. Oxidized cornstarch—Urea wood adhesive for interior particleboard production. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 110, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Xu, W. Synthesis and Characterization of Starch-based Aqueous Polymer Isocyanate Wood Adhesive. BioResources 2015, 10, 7653–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meimoun, J.; Wiatz, V.; Saint-Loup, R.; Parcq, J.; Favrelle, A.; Bonnet, F.; Zinck, P. Modification of starch by graft copolymerization. Starch-Stärke 2017, 1600351, 1600351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, L. Preparation, characterization and properties of starch-based wood adhesive. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ud-Din; Chen, L.; Ullah, I.; Wang, P.K.; Javaid, A.B.; Hu, C.; Zhang, M.; Ahamd, I.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Z. Synthesis and characterization of starch-g-poly(vinyl acetate-co-butyl acrylate) bio-based adhesive for wood application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.J.F.; Curvelo, A.A.S.; Gandini, A. Surface chemical modification of thermoplastic starch: Reactions with isocyanates, epoxy functions and stearoyl chloride. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Du, G. Performance of urea-formaldehyde adhesive with oxidized cassava starch. BioResources 2017, 12, 7590–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q.; Mao, A.; Li, J. Toughening and enhancing melamine-urea-formaldehyde resin properties via in situ polymerization of dialdehyde starch and microphase separation. Polymers 2019, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aristri, M.A.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Iswanto, A.H.; Fatriasari, W.; Sari, R.K.; Antov, P.; Gajtanska, M.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Pizzi, A. Bio-Based Polyurethane Resins Derived from Tannin: Source, Synthesis, Characterisation, and Application. Forests 2021, 12, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristri, M.A.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Yadav, S.M.; Antov, P.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Pizzi, A.; Fatriasari, W.; Ismayati, M.; Iswanto, A.H. Recent Developments in Lignin- and Tannin-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Resins for Wood Adhesives—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ud-Din; Xiong, H.; Wang, Z.; Fei, P.; Ullah, I.; Javaid, A.B.; Wang, Y.; Jin, W.; Chen, L. Effects of sucrose fatty acid esters on the stability and bonding performance of high amylose starch-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Guo, H.; Gu, Z.; Li, Z.; Hong, Y. Effects of compound emulsifiers on properties of wood adhesive with high starch content. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 72, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilpiszewska, K.; Spychaj, T. Chemical modification of starch with hexamethylene diisocyanate derivatives. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 70, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazeed, A.; Farag, S.; Shaarawy, S.; Hebeish, A. Chemical modification of starch via etherification with methyl methacrylate. Starch/Staerke 1998, 50, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Zhang, Y.; Smeets, N.; Cunningham, M.; Dubé, M. On the Use of Starch in Emulsion Polymerizations. Processes 2019, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duarah, R.; Karak, N. A starch based sustainable tough hyperbranched epoxy thermoset. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 64456–64465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Qu, W.; Cheng, J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F. Green synthesis and properties of an epoxy-modified oxidized starch-grafted styrene-acrylate emulsion. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 123, 109412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, F.; Peng, H.; Peng, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J. Preparation of Novel c-6 Position Carboxyl Corn Starch by a Green Method and Its Application in Flame Retardance of Epoxy Resin. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 11944–11952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvergne, R.; Caillol, S.; David, G.; Boutevin, B.; Pascault, J.P. Biobased thermosetting epoxy: Present and future. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1082–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Qiu-hua, W.; Xue-Chun, X.; Wen-yong, J.; Shu-Cai, G.; Hai-Feng, Z. Oxidation of cornstarch using oxygen as oxidant without catalyst. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Du, C.; Qiang, Y. Preparation and Properties of Cornstarch Adhesive. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 5, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarusombuti, S.; Bauchongkol, P.; Hiziroglu, S.; Fueangvivat, V. Properties of Rubberwood Medium-Density Fiberboard Bonded with Starch and Urea-Formaldehyde. For. Prod. J. 2012, 62, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Olsson, E.; Plivelic, T.S.; Andersson, R.; Johansson, C.; Kuktaite, R.; Järnström, L.; Koch, K. Molecular structure of citric acid cross-linked starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, P.H.; Nam, T.T.; Van Phuc, M.; Hiep, N.A.; Van Thanh, T.; Vuong, N.T.; Xuan, D.D. Oxidized Maize Starch: Characterization and Effect of It on the Biodegradable Films.Ii. Infrared Spectroscopy, Solubility of Oxidized Starch and Starch Film Solubility. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 55, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, X.F.; Peng, L.Q.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Zhang, H. Environment-friendly urea-oxidized starch adhesive with zero formaldehyde-emission. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 181, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Du, G. Enhanced performance of urea–glyoxal polymer with oxidized cassava starch as wood adhesive. Iran. Polym. J. 2019, 28, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujka, M. Ultrasonic modification of starch—Impact on granules porosity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 37, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čížová, A.; Sroková, I.; Sasinková, V.; Malovíková, A.; Ebringerová, A. Carboxymethyl starch octenylsuccinate: Microwave- and ultrasound-assisted synthesis and properties. Starch/Staerke 2008, 60, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Cui, D. Synthesis of carboxymethyl potato starch and comparison of optimal reaction conditions from different sources. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2008, 19, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.T.; Uthumporn, U.; Karim, A.A.; Cheng, L.H. The influence of ultrasound on the degree of oxidation of hypochlorite-oxidized corn starch. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Fu, X.; He, X.; Luo, F.; Gao, Q.; Yu, S. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical properties of maize starches differing in amylose content. Starch/Staerke 2008, 60, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.J.; Lim, H.S.; Lim, S.T. Effect of partial gelatinization and retrogradation on the enzymatic digestion of waxy rice starch. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 43, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, D.; Lv, J.; Wu, C.; Zhou, W.; Zia-ud-Din. Effects of various durations of enzyme hydrolysis on properties of starch-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, P.; Cui, B.; Kang, X.; Yu, B.; Qiu, L.; Sun, C. Effects of pullulanase debranching on the properties of potato starch-lauric acid complex and potato starch-based film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Ou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, H. Effects of pullulanase pretreatment on the structural properties and digestibility of lotus seed starch-glycerin monostearin complexes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 240, 116324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia-ud-Din; Xiong, H.; Fei, P. Physical and chemical modification of starches: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2691–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristak, L.; Antov, P.; Bekhta, P.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Iswanto, A.H.; Reh, R.; Sedliacik, J.; Savov, V.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; et al. Recent progress in ultra-low formaldehyde emitting adhesive systems and formaldehyde scavengers in wood-based panels: A review. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Policardi, F. Wood composites and their polymer binders. Polymers 2020, 12, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, W.; Aprilliana, N.; Asmara, S.; Bakri, S.; Hidayati, S.; Banuwa, I.S.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Iswanto, A.H. Performance of eco-friendly particleboard from agro-industrial residues bonded with formaldehyde-free natural rubber latex adhesive for interior applications. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 2222–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averina, E.; Konnerth, J.; van Herwijnen, H.W.G. Protein-based glyoxal–polyethyleneimine-crosslinked adhesives for wood bonding. J. Adhes. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Labib, A.; Sudarmanto; Akbar, F.; Nuryawan, A.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Papadopoulos, A.N.; Pizzi, A. Influence of Lignin Content and Pressing Time on Plywood Properties Bonded with Cold-Setting Adhesive Based on Poly (Vinyl Alcohol), Lignin, and Hexamine. Polymers 2022, 14, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savov, V.; Valchev, I.; Antov, P.; Yordanov, I.; Popski, Z. Effect of the Adhesive System on the Properties of Fiberboard Panels Bonded with Hydrolysis Lignin and Phenol-Formaldehyde Resin. Polymers 2022, 14, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Pizzi, A.; Fredon, E.; Gerardin, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, B.; Du, G. Low curing temperature tannin-based non-isocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) wood adhesives: Preparation and properties evaluation. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 112, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi Tannins: Prospectives and Actual Industrial Applications. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 344. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moubarik, A.; Pizzi, A.; Allal, A.; Charrier, F.; Charrier, B. Cornstarch and tannin in phenol-formaldehyde resins for plywood production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 30, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Park, B.-D. Modification of urea-formaldehyde resin adhesives with oxidized starch using blocked pMDI for plywood. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pizzi, A.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, X.; Fredon, E.; Gerardin, C.; Du, G. Particleboard bio-adhesive by glyoxalated lignin and oxidized dialdehyde starch crosslinked by urea. Wood Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Q.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of glycidyl methacrylate grafted starch adhesive to apply in high-performance and environment-friendly plywood. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Pizzi, A.; Lei, H.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Du, G. Environmentally friendly chitosan adhesives for plywood bonding. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 112, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Essawy, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, X.; Du, G. Preparation of a starch-based adhesive cross-linked with furfural, furfuryl alcohol and epoxy resin. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 110, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswanto, A.H.; Azhar, I.; Supriyanto; Susilowati, A. Effect of resin type, pressing temperature and time on particleboard properties made from sorghum bagasse. Agric. For. Fish. 2014, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Z.; Furuno, T.; Katoh, S.; Nishino, Y. Effects of urea–formaldehyde resin mole ratio on the properties of particleboard. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, K.M.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Hiziroglu, S.; Wan Nadhari, W.N.A.; Abd Karim, N.; Jumhuri, N.; Ang, L.Z.P. Evaluation of properties of starch-based adhesives and particleboard manufactured from them. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lum, W.C.; Boon, J.G.; Kristak, L.; Antov, P.; Pędzik, M.; Rogoziński, T.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Rahandi Lubis, M.A.; Fatriasari, W.; et al. Particleboard from Agricultural Biomass and Recycled Wood Waste: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4630–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.S.; Hashim, R.; Amini, M.H.M.; Sulaiman, O.; Hiziroglu, S. Evaluation of the properties of particleboard made using oil palm starch modified with epichlorohydrin. BioResources 2013, 8, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, M.E.; Sulaiman, O.; Hashim, R.; Hiziroglu, S.; Nadhari, W.N.A.W.; Sulaiman, N.S.; Razali, M.Z. Measurement of some particleboard properties bonded with modified carboxymethyl starch of oil palm trunk. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2014, 53, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaming, J.; Heng, N.B.; Owodunni, A.A.; Lamaming, S.Z.; Khadir, N.K.A.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Mohamad Kassim, M.H.; Hussin, M.H.; Bustami, Y.; et al. Characterization of rubberwood particleboard made using carboxymethyl starch mixed with polyvinyl alcohol as adhesive. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 183, 107731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Karim, N.; Lamaming, J.; Yusof, M.; Hashim, R.; Sulaiman, O.; Hiziroglu, S.; Wan Nadhari, W.N.A.; Salleh, K.M.; Taiwo, O.F. Properties of native and blended oil palm starch with nano-silicon dioxide as binder for particleboard. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahfitri, A.; Hermawan, D.; Kusumah, S.S.; Ismadi; Lubis, M.A.R.; Widyaningrum, B.A.; Ismayati, M.; Amanda, P.; Ningrum, R.S.; Sutiawan, J. Conversion of agro-industrial wastes of sorghum bagasse and molasses into lightweight roof tile composite. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutiawan, J.; Hadi, Y.S.; Nawawi, D.S.; Abdillah, I.B.; Zulfiana, D.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Nugroho, S.; Astuti, D.; Zhao, Z.; Handayani, M.; et al. The properties of particleboard composites made from three sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) accessions using maleic acid adhesive. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Committee for Standardization, EN 312. Particleboards–Specifications; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, P.; Owusu, F.W.; Mitchua, S.J.; Kusi, E.; Frimpong-Mensah, K. Some Mechanical Properties of Particleboards Produced from Four Agro-Forest Residues Using Cassava Starch and Urea Formaldehyde as Adhesives. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 11, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-K.; Hsu, C.-H.; Hsu, P.-K.; Cho, Y.-M.; Chou, T.-H.; Cheng, Y.-S. Preparation and evaluation of particleboard from insect rearing residue and rice husks using starch/citric acid mixture as a natural binder. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 12, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotikhun, A.; Hiziroglu, S.; Buser, M.; Frazier, S.; Kard, B. Characterization of nano particle added composite panels manufactured from Eastern red cedar. J. Compos. Mater. 2018, 52, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarski, C.M.; de Francisco, A.C.; da Luz, L.M.; Kovaleski, J.L.; Silva, D.A.L. Life cycle assessment of medium-density fiberboard (MDF) manufacturing process in Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDevitt, J.E.; Grigsby, W.J. Life Cycle Assessment of Bio- and Petro-Chemical Adhesives Used in Fiberboard Production. J. Polym. Environ. 2014, 22, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Hong, M.K.; Park, B.D. Hydrolytic Removal of Cured Urea–Formaldehyde Resins in Medium-Density Fiberboard for Recycling. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2018, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.A.R.; Hong, M.-K.; Park, B.-D.; Lee, S.-M. Effects of recycled fiber content on the properties of medium density fiberboard. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2018, 76, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Palazuela Conde, J.; Davis, S.J.; Wise, W.R. Starch as a replacement for urea-formaldehyde in medium density fibreboard. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffael, E.; Schneider, T.; Dix, B. Influence of moisture content on the formaldehyde release of particle- and fibreboards bonded with tannin–formaldehyde resins. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2015, 73, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.; Han, G.-S.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, I.-G.; Kim, Y.-H.; Oh, S.C. Adhesive Properties of Medium-Density Fiberboards Fabricated with Rapeseed Flour-Based Adhesive Resins. J. Adhes. 2014, 90, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlova, J.; Savov, V.; Simeonov, T. Effect of the content of corn stalk fibres and additional heat treatment on properties of eco-friendly fibreboards bonded with lignosulphonate. Drewno 2022, 65, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, B.; Yuan, B.; Guo, M. Preparation and characterizations of a chitosan-based medium-density fiberboard adhesive with high bonding strength and water resistance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 176, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cai, Z.; Horn, E.; Winandy, J.E. Effect of oxalic acid pretreatment of wood chips on manufacturing medium-density fiberboard. Holzforschung 2011, 65, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, M.; Cofta, G.; Doczekalska, B.; Bonenberg, A. Fungi in Mycelium-Based Composites: Usage and Recommendations. Materials 2022, 15, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J.F.; Supan, K. Binderless fiberboard: Comparison of fiber from recycled corrugated containers and refined small-diameter whole treetops. For. Prod. J. 2006, 56, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Theng, D.; Arbat, G.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Vilaseca, F.; Ngo, B.; Mutjé, P. All-lignocellulosic fiberboard from corn biomass and cellulose nanofibers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, F.; Yu, L.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Thermal processing of starch-based polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 1348–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian-qing, X.; Ying-ying, Y.; Yi-ting, N.; Liang-ting, Z. Development of a cornstarch adhesive for laminated veneer lumber bonding for use in engineered wood flooring. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazerian, M.; Razavi, S.A.; Partovinia, A.; Vatankhah, E.; Razmpour, Z. Prediction of the Bending Strength of a Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) Using an Artificial Neural Network. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2020, 56, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.; Schneider, L.; Razi, H.; Trachsel, E.; Faude, E.; Koch, S.M.; Masania, K.; Fratzl, P.; Keplinger, T.; Burgert, I. High-Performance All-Bio-Based Laminates Derived from Delignified Wood. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9638–9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.Q.; Bao, Y.L.; Guo, W.J.; Fang, L.; Wu, Z.H. Preparation and application of high performance corn starch glue in straw decorative panel. Wood Fiber Sci. 2018, 50, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H2O2/Starch Mole Ratio | Solids Content (%) | Viscosity (mPa·s) | Gelation Time (s) | Mw (g/mole) | Mn (g/mole) | Polydispersity Index (PDI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 48.43 | 107.7 | 532 | 11,882 | 9881 | 1.19 |

| 1.0 | 41.82 | 76.0 | 547 | 11,000 | 9547 | 1.15 |

| 1.5 | 37.94 | 60.7 | 560 | 9835 | 8890 | 1.11 |

| 2.0 | 31.20 | 45.3 | 587 | 8010 | 7657 | 1.05 |

| H2O2/Starch Mole Ratio | B-pMDI Level (wt%) | CA Level (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 7.5 | 10 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Control | 0.61 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.06) | ||||

| 0.5 | 0.95 (0.08) | 1.13 (0.07) | 1.35 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.07) | 0.96 (0.07) | 0.98 (0.05) |

| 1.0 | 0.96 (0.05) | 0.97 (0.07) | 0.99 (0.06) | 1.01 (0.07) | 1.05 (0.08) | 1.18 (0.07) |

| 1.5 | 0.94 (0.10) | 0.96 (0.04) | 0.98 (0.04) | 1.00 (0.08) | 1.04 (0.09) | 1.08 (0.05) |

| 2.0 | 0.85 (0.12) | 0.92 (0.12) | 0.96 (0.12) | 0.90 (0.11) | 0.92 (0.10) | 0.94 (0.10) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maulana, M.I.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Febrianto, F.; Hua, L.S.; Iswanto, A.H.; Antov, P.; Kristak, L.; Mardawati, E.; Sari, R.K.; Zaini, L.H.; et al. Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review. Forests 2022, 13, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101614

Maulana MI, Lubis MAR, Febrianto F, Hua LS, Iswanto AH, Antov P, Kristak L, Mardawati E, Sari RK, Zaini LH, et al. Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review. Forests. 2022; 13(10):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101614

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaulana, Muhammad Iqbal, Muhammad Adly Rahandi Lubis, Fauzi Febrianto, Lee Seng Hua, Apri Heri Iswanto, Petar Antov, Lubos Kristak, Efri Mardawati, Rita Kartika Sari, Lukmanul Hakim Zaini, and et al. 2022. "Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review" Forests 13, no. 10: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101614

APA StyleMaulana, M. I., Lubis, M. A. R., Febrianto, F., Hua, L. S., Iswanto, A. H., Antov, P., Kristak, L., Mardawati, E., Sari, R. K., Zaini, L. H., Hidayat, W., Giudice, V. L., & Todaro, L. (2022). Environmentally Friendly Starch-Based Adhesives for Bonding High-Performance Wood Composites: A Review. Forests, 13(10), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101614