Abstract

With the increasing concerns about the environmental issues of forest health tourism, the environmentally responsible behavior of tourists becomes the key to the sustainable development of forest health tourism. Therefore, the article takes experiential value as an entrance point, innovatively introduces the scenario of forest health tourism, and divides experiential value into the functional value, hedonic value and symbolic value. Then, a theoretical model of the experiential value of forest health tourism, two place perception concepts of place attachment, and environmentally responsible behavior is constructed. The research team assembled 498 valid questionnaires for the empirical investigation in the Fuzhou National Forest Park in China. Structural equation modeling was used to test the theoretical hypotheses and to explore the cumulative driving effects of the experiential value and place attachment in forest health tourism on environmentally responsible behavior. The results showed that the experiential value of forest health tourism had a significant positive effect on the environmentally responsible behavior. It also had a significant positive effect on place attachment, which also strengthened the environmentally responsible behavior. In addition, place attachment is considered to be an important mediator of the effect of forest health tourism’s experiential value on the intention of environmentally responsible behavior. Place attachment is a more important element driving environmentally responsible behavior than the elements of the forest health tourism’s experiential value. Place attachment has a greater impact on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior than place identification. This highlights the importance of place attachment in influencing the environmentally responsible behavior of tourists. These results provide a useful theoretical basis and practical reference for promoting environmentally responsible behavior in forest health tourism.

1. Introduction

Rapidly advancing urbanization has brought about the problems of a high population density and a fast pace of production and life in urban communities, leading to a rising number of sub-healthy people in cities. According to the relevant data, the proportion of sub-healthy urban workers in China is as high as 76%, of which nearly 60% are in an overworked state [1]. In addition, the proportion of aging in China has reached 17%, and the society is facing many problems and challenges regarding one’s pension, medical, and spiritual support. In this context, there is an urgent desire to return to the forest and an urgent requirement to enter the quality forest environment for forest health tourism [2]. According to studies, dense forests can regulate the human nervous system, eliminate toxic bacteria, purify the air, and regulate the temperature to form a warm winter and cool summer microclimate [3]. At the same time, the abundant negative oxygen ions and phleomycin in forests can improve one’s sleep quality, enhance human immunity, and play a role in treating some chronic diseases such as cancer and hypertension [4]. Therefore, forest recreation is considered to be a health activity with a low investment and a high return, which gradually becomes a new perspective of tourism marketing communication in the post-pandemic era [5] and promotes the development of the health industry.

However, due to the lack of a good management, the improper behaviors of tourists, such as littering, spitting, and graffitiing, and the destruction of public areas can directly or indirectly affect or even destroy the physical environment of forest tourism, which has a great negative impact on the environment for recreation products and recreation activities, and it degrades many natural attractions [6]. Therefore, it is crucial for the management of tourist areas to guide tourists to actively participate in environmentally responsible behavior (abbreviated as ERB later) during forest health tourism [7].

It has been shown that service quality [8], perceived value [9], and leisure involvement [10] have significant positive effects on one’s ERB. The ERB people exemplify can effectively reduce the management pressure of the tourism management department and promote the sustainable development of tourism areas. However, previous research dynamics mainly focused on behavioral intention [11], a willingness to revisit [12], and happiness [13], which often ignored the influence of experiential value on ERB. According to the experiential value theory [14], the experiential value of forest health tourism is the psychological feeling of pleasure which is obtained by tourists. The pleasure comes from the satisfaction of the basic physiological and psychological needs of tourists by the efficacy of recreation products and services provided by scenic spots on the one hand, and the satisfaction of higher-level psychological needs inherent in tourists on the other. As Maslow proposed the “peak experience” of self-actualization [15], the dissatisfaction of tourists’ experiential feelings during the tour process will directly or indirectly cause negative emotions in tourists, leading to the diminution or even disappearance of place attachment, which results in the undesirable behavior of environmental destruction [16]. Meanwhile, some scholars have found that the attachment of tourists to a place directly affects their intrinsic behavioral intentions [17]. Tourists with attachment emotions have a stronger sense of environmental protection and are more likely to take the initiative for ERB [18]. Cheng and Wu examined the effects of tourists’ environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment on ERB in island tourism. The results showed that place attachment was an effective predictor variable of tourists’ ERB [19]. Hosany et al. verified the mediating effect of place attachment in the relationship between tourists’ emotions and the recommendation intention [20].

Research on ERB has often focused on national parks [21], historic districts [22], and comprehensive parks [23], with little attention on forest recreation. With an increasing amount of attention being paid to forest health tourism, the ERB of tourists has become the key to the sustainable development of forest health tourism [24]. Consequently, this study attempts to develop a theoretical model to assess the influence of experiential values on place attachment and ERB in forest health tourism. It is expected to improve the explanation and prediction of ERB, enrich and expand its research horizon, and provide reference for future generations to construct integrated models. At the same time, it provides a theoretical guidance for forest managers to take effective measures to cultivate and guide the ERB of tourists.

2. Related Theories

2.1. Forest Recreation

Forest recreation is an activity that uses various elements of forests to strengthen immunity, prevent disease, and promote health [25]. Foreign scholars have mostly studied specific populations to explore the impact of special forest recreation activities on human health [26]. Additionally, domestic researchers in the field of tourism mostly start from the supply side and discuss how to develop forest health tourism based on forest resources [27]. From 2016 to 2019, the average annual growth rate of forest health tourists in China reached 14.5%. In the second half of 2020, forest recreation overcame the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the annual tourist volume reached 84.2% of the 2019 tourist volume [28]. While forest recreation has created a tourism boom, it has also brought about many problems. Jia found that the lack of proper mechanisms to guide the tourism industry can lead to the breakage and waste of ecological resources [29]; Wang et al. argued that the lack of environmental awareness and concepts among tourists can lead to the repeated destruction of tourism resources [30]. Subsequently, both Hanavan [31] and Gupta [32] found that it is necessary to guide positive ERB to ensure that the public can enjoy the social benefits of forest recreation in an equitable manner.

2.2. Experiential Value of Forest Health Tourism

The experiential value is a physical and mental sensation that is obtained by the tourist in the tourism world when he or she is deeply integrated with the present situation, and it consists of two main aspects: the material and spiritual [33]. The first is the functional experience, which is the basic condition for the tourist to be able to adapt to forest health tourism. Babin [34] and Walls [35] have pointed out that the functional experience is the fastest way to obtain the tourists’ evaluation of the product and helps the scenic area to improve its service quality. The second is the hedonic experience, which can elicit cognitive judgment and creative thinking from customers and help visitors to develop positive emotions and achieve brand loyalty to the product or service of recreation. This has a positive contribution to place dependence, place identification, and tourist loyalty [36]. In fact, scholars have different classifications of experiential value due to the different research fields, research objects, and research purposes [10]. For forest health tourism, besides the functional and hedonic value, we also need to pay attention to its “scientific education” function. During forest health tourism, activities such as “forest class”, “gardening”, “flower arranging”, “bird watching”, etc., all promote communication and learning among tourists in varying degrees and strengthen the symbolic memory of “forest health”. Na [37] found that tourists’ novelty and curiosity about tourist places enhance the tourists’ happiness of their travel. This research investigates the experiential value of forest health tourism in three dimensions: functional, hedonic, and symbolic based on the above theories, case studies, and characteristics of forest health tourism.

2.3. Place Attachment

Place attachment has been a hot topic in environmental psychology, recreation geography, and leisure research. The duration of individual-place interactions is an important factor that influences the formation of place attachment. It is believed that as people’s contact time with places grows, they gradually begin to understand them and give them meaning [38]. In 1977, Gerson et al. introduced the term place attachment but did not give a clear definition [39]. Wiliams argues that place attachment is composed of at least two dimensions: place dependence and place identification. Place dependence is the functional dependence of the tourist on the tourist place; place identification is the emotional attachment resulting from the special meaning that the tourist assigns to the place [40]. The statement has been widely used in various subsequent empirical studies. Tang et al. developed a new vision of the relationship between place attachment and the management model of national parks. They confirmed the scientific validity of dividing and quantifying place attachment into place dependence and place identification [41]. Therefore, this study divides place attachment into two dimensions: place dependence and place identification.

2.4. Environmentally Responsible Behavior

Environmentally responsible behavior (ERB), also known as pro-environmental behavior, refers to the behavior of tourists who refuse to damage the environment and lead others to take the initiative to protect it [42]. Since ERB is closely related to the concept of the sustainable development of the forest health industry, many scholars have explored the formation mechanisms and influencing factors of ERB [43]. Currently, most of the used unidimensional measurement instruments have been adapted from well-established general scales [44]. A few scholars consider ERB to be a multidimensional variable [6]. This study follows the majority of scholars to test the boosting effect of experiential value on inducing ERB in forest health tourism with a single variable.

3. Hypothesis Formulation

3.1. Experience Value and Place Attachment of Forest Health Tourism

The experiential value of forest health tourism evaluates the quality of forest health tourism from the perspective of tourists and proposes targeted national policies or regulations. It emphasizes the functional and emotional changes that visitors experience in the environment of forest recreation and is based on the concept of the “experiential value” in tourism. In contrast to the experiential value in tourism, the forest environment is the main driver that influences tourists’ behavioral preferences [45], and its functional value [46], emotional experience [47], and economic value [48] have direct and indirect effects on one’s travel intentions [49]. Based on SOR theory, Luo explored the relationship between perception and ERB and he argued that a reasonable layout of the interpretation system and improved educational content could help to enhance ERB [50]. Na and Xie et al. also proposed that tourism’s experiential value is a multidimensional concept [51]. Therefore, this study classified forest health tourism’s experiential value into three dimensions according to the actual situation: (1) the functional value, which emphasizes tourists’ perceptions of the material aspects of forest recreation, including hotels, restaurants, transportation, and services; (2) the hedonic value, which emphasizes actors’ emotional states in forest health, including emotions such as rehealing, relaxation, escape, and communication; and (3) the symbolic value, which emphasizes tourists’ experiences after self-identity and social belonging, including freshness, social status, knowledge acquisition, etc.

Empirical research found that forest health tourism has a direct and significant effect on environmental preferences [52], and there is also a direct positive influence path of environmental preferences on place attachment [53]. Therefore, a positive path of the “experiential value of forest health tourism—place attachment” has been established. This study proposes six hypotheses based on three dimensions of experiential value and two dimensions of place attachment.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Functional value has a significant positive effect on place attachment.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Hedonic value has a significant positive effect on place attachment.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Symbolic value has a significant positive effect on place attachment.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Functional value has a significant positive effect on place identification.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Hedonic value has a significant positive effect on place identification.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Symbolic value has a significant positive effect on place identification.

3.2. Place Attachment and ERB

Place attachment can be used as an antecedent variable to predict tourists’ ERB [54] and can also have a mediating effect that indirectly influences differences in ERB at different place attachment levels [55]. It is shown that in forest health tourism, tourists with place attachment are able to develop a strong sense of environmental protection and behaviors to maintain the stability of the place compared to those without place attachment [56]. Different levels of place attachment can have different effects on tourists’ attitudes and behavioral intentions [57]. Therefore, this study argues that tourists with higher levels of place attachment have stronger motivations for self-determination. Specifically, when tourists engage in recreational activities, those with higher levels of attachment to recreational activities will generate higher internal and external motivations than those with lower levels, and thus they will be more willing to engage in ERB. In this study, we propose two hypotheses for the influence of two dimensions in place attachment on ERB.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Place attachment has a significant positive effect on ERB.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Place identification has a significant positive effect on ERB.

3.3. Place Attachment and Place Identification

In forest health tourism, the formation of place dependence is determined by a comparative judgment with other tourist places, and the tourist needs to choose which place is the best one for them which they like to visit the most. Place identification is a special emotion that requires individuals to pay more time and expense to the tourist destination. The formation of it usually takes a long time. It can be said that people rely on “forest recreation” and continue to visit the places first, and then develop a place identification with “forest recreation”. Vasco and Corbin confirmed that place dependence influences people’s attitudes and daily behaviors toward the resource environment mainly through the mediating role of place identification [58]. Gifford pointed out that place identification emphasizes the positive emotional attachment of people to places psychologically, which lasts and changes with time [59]. Therefore, in order to clarify the sequential relationship between place dependence and place identification, hypothesis 9 was proposed.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Place dependence has a significant positive effect on place identification.

3.4. Experiential Value and ERB of Forest Health Tourism

In forest health tourism, there is a strong link between a tourists’ perception of their experience and their individual behavior. It has been shown that service quality [60], hygienic environment [6], and brand influence [61] of tourist attractions can influence individual behavior in a certain manner. In addition, people with experience in forest health tourism will be more adept at proactively protecting the forest environment [25]. ERB is enhanced when tourists are immersed in a self-indulgent hedonic experience or when they experience the sensory and emotional value of a more comfortable and satisfying experience in “forest recreation”. In fact, effective outdoor activities can lead to a reflection on humanity and nature [62]. This is because the practice of “forest recreation” provides a new opportunity for tourists to get to know nature, which satisfies the pleasure of gaining knowledge in forest health tourism and effectively motivates them to protect the forest environment. Therefore, it is essential to examine the relationship between the experiential value of forest health tourism and ERB. Therefore, based on the three dimensions of the experiential value of forest health tourism, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Functional value has a significant positive effect on ERB.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Hedonic value has a significant positive effect on ERB.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Symbolic value has a significant positive impact on ERB.

4. Data Collection and Methodology

4.1. Overview of the Study Area

Fuzhou National Forest Park is located in the northern suburbs of Fuzhou City, China, which is a comprehensive park integrating scientific research and sightseeing. The park has convenient external transportation and complete facilities. It has a more than 50% plant coverage, rich scenic resources, comfortable climatic conditions, and superior atmospheric environmental indicators. Fuzhou National Forest Park has been open to the public for free since 2008 and is popular among city residents and visitors. Since 2018, the government has been committed to building Fuzhou National Forest Park as a demonstration base for forest recreation and forest experience. However, due to the large number of people in the forest park, the different ages, qualities, and visiting habits of visitors, uncivilized behaviors such as disturbing plant habitats and breaking recreational facilities occur frequently in the park, which have caused great economic losses. The park has to spend excessive labor and financial resources to stop tourists’ environmental damage and restore the forest environment, which impedes the benign development of the forest park. Guiding the ERB in forest health tourism can lead to the maintenance and further development of the forest health environment. Therefore, the selection of Fuzhou National Forest Park as the object of empirical research has a greater practical significance and reference value.

4.2. Model Construction

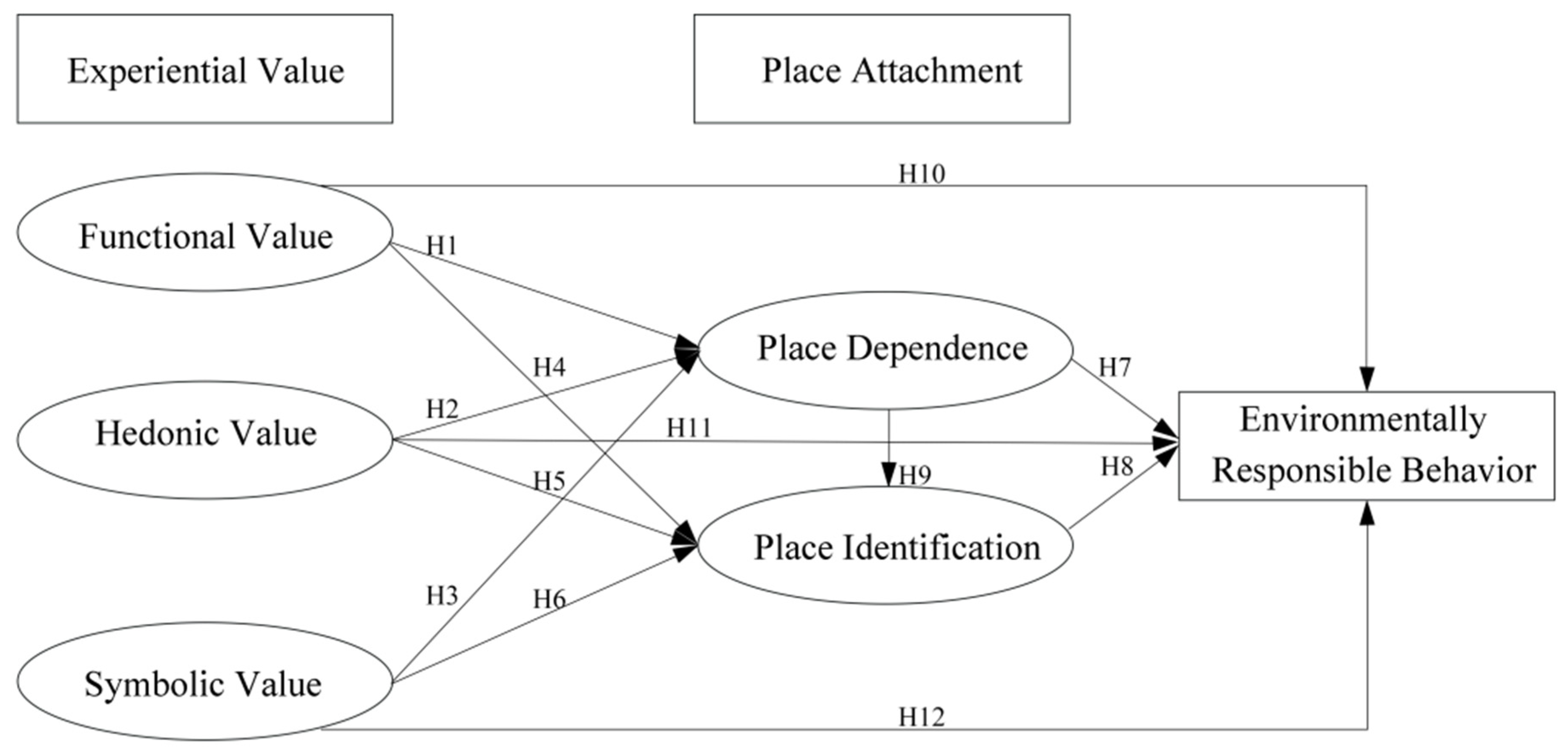

Arousal theory is a theory in environmental psychology that focuses on the relationship between the environment and human behavior [63]. Bagozzi contends that assessments encourage emotions and further impact people’s behavior or behavioral intentions [64]; in other words, the “evaluation–emotion–behavior” change process. Therefore, based on arousal theory, this study constructs a research model of experiential value (cognitive evaluation), place attachment (emotional response), and ERB (emotional initiation outcome) in forest health tourism by taking experiential value as a cognitive evaluation variable; place attachment as an emotional response variable; and ERB as an outcome of the emotional initiation variable (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model.

4.3. Questionnaire Setup and Distribution

The questionnaire setting is mainly divided into two parts, the first part is the sample characteristics of the respondent group and is based on single-choice questions. The second part consisted of specific questions for the three latent variables, with the referenced previous research and modified to fit the actual research context. A seven-point Likert scale (from 1 to 7, indicating from strongly disagree to strongly agree) was used for each question item. Among them, the forest health tourism experiential value was set by 33 questions that explored the functional, hedonic, and symbolic values by Na [37], Li et al. [65], and Xie [66]. Place attachment was set by six questions by Williams et al. [40] and Tang et al. [67] that explored place dependence and place identification. ERB was set with three questions referring to Cheng [19], Qiu [16] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Questionnaire scale settings.

The questionnaire was collected by the research team from March to June 2022. The research team was systematically trained and could explain every doubt about the questionnaire for the respondents. Due to the limitations of the research conditions and research funding, it was not available to investigate all the visiting tourists. Therefore, a simple random sampling method was used to select the respondents. To enhance the respondents’ patience and enthusiasm in answering the questionnaire, we prepared a present for each respondent. First, we collected 150 questionnaires from visitors and employees at park entrances and exits, visitor centers, and forest trails as a pre-survey. Second, the preliminary questionnaire results, field interviews, suggestions from park employees, and experts’ opinions were combined to modify the questions that generated an ambiguity or were meaningless and to form the final questionnaire. Last, the research team invited tourists of different age groups to participate in the survey one-on-one at forest lawns and on forest trails in the Fuzhou National Forest Park, where the number of people is large and the stay time is long. Five hundred and forty questionnaires were collected by the research team. After eliminating the questionnaires with omissions, haphazard responses, short response times, and obvious patterns, 498 valid questionnaires were retained. The effective rate of the questionnaires reached 92.22%.

4.4. Analysis Method

The structural equation modeling integrates the measurement model of the factor analysis and the structural formula of the path analysis, with a complete framework for the data analysis. The structural equation modeling differs from the traditional multiple regression methods. It has the ability to construct multiple dependent variables simultaneously; besides being able to construct unobserved latent variables, it can analyze the relationships between latent variables as well. Therefore, structural equation modeling is used commonly to test theoretical models and influence the relationships between the factors of each dimension [68]. AMOS is a software that explores the relationships between variables by using structural equations. It has a visual mobile plotting tool that allows for the convenient construction of structural equation models to examine the interactions between variables and the reasons of the formation. AMOS is user-friendly but powerful, and it has been widely used in studies related to structural equation modeling [69].

Studies generally require a ratio of the observed variables to the sample size between 1:10 and 1:25 [70]. This questionnaire consists of 42 questions. Therefore, a sample size of 420–1050 is appropriate. The number of 498 questionnaires met the requirements of the SEM analysis and allowed for the data analysis. First, the descriptive statistics and reliability analysis of the collected sample data were performed by SPSS 26.0 software. Then, structural equation modeling was constructed with AMOS 26.0 software, and the validating factor analysis and parameter calculations were conducted to test whether the research hypotheses were valid. Finally, boot-strap sampling (samples were selected 5000 times) was used to test whether the mediating effect of place attachment was significant.

In view of the limitations of AMOS software in the analysis of multiple mediating effects, “defined estimands” were used to test the mediating effects of place attachment through “bias-corrected”, a “95% confidence interval estimation”, and a “significant p-value”. The model was simplified by reducing the “latent variables” in the original model to the “observed variables”, referring to the study of Huang et al. [71]. Before analyzing the measurement model, the mean of each question in the four sub-dimensions of the hedonic value and the three sub-dimensions of the symbolic value of the experiential value was used as the score of each sub-dimension. The same operation was performed in the previous dimension to construct a new structural equation model.

5. Results

5.1. Sample Description

As shown in Table 2, the valid questionnaires were analyzed. In terms of gender, women accounted for 54.4% of the total sample, while men accounted for 45.6%. In terms of education level, the highest percentage was those with undergraduate degrees (30.6%), and the lowest percentage was those with doctoral degrees (17.1%). In the age analysis, the highest percentage was among those aged 31–40 (21.5%), and the lowest was among those aged under 18 (2.4%). In terms of occupation, teachers, doctors, and other career workers dominated (26.3%), followed by company or corporate employees (18.3%). In terms of one’s monthly personal income, the highest percentage was among those who earn RMB 4000–6999 (23.7%), and the lowest was among those who earn less than RMB 1000 (7.6%). In terms of modes of travel, the highest percentage was those who were self-driving (40.0%), and the lowest was those who travelled by a high-speed train (2.4%). The above data are consistent with the structural characteristics of the forest park visitors and can be used for subsequent experimental studies.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

The data were analyzed for its reliability, validity, and mean value. The results are shown in Table 3. A statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software, and the results showed that Bartlett’s spherical tests for the functional value (A), hedonic value (B), symbolic value (C), place dependence (D), place identification (E), and ERB (F) of forest health tourism were significant, the KMO coefficient was 0.924, and Cronbach’s alpha were 0.925, 0.916, 0.932, 0.899, 0.850, 0.940, 0.897, 0.896, 0.909, 0.895, and 0.803, all of which were higher than 0.8 [72]. A factor analysis could be performed on them.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and reliability analysis.

A factor analysis was performed on each latent variable, and the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.604 to 0.910, higher than the minimum critical threshold of 0.5. The combined reliability (CR) values for each latent variable ranged from 0.781 to 0.953, higher than the critical threshold of 0.7 [73]. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for each latent variable were 0.803, 0.789, 0.777, 0.713, 0.513, 0.797, 0.698, and 0.619, higher than the critical threshold value of 0.5 [74]. The results indicated that the convergent validity of each latent variable was good [75]. The specific parameters are shown in Table 3.

The mean values of the functional value (A), hedonic value (B), symbolic value (C), place dependence (D), place identification (E), and ERB (F) were 5.375, 5.652, 4.502, 5.672, 5.628, and 5.739, which were in the “somewhat agree–agree” range of the Likert scale. The overall satisfaction of the visitors with the forest park is high. One’s place attachment and ERB improved significantly when the experiential value increased. It indicates the necessity of further research regarding the relationship between the three.

5.3. Index of Fit of Structural Equation Model and Adjustment Scheme

The parameters of the initial structural model were calculated by AMOS 26.0 software. The overall model fit index x2/DF = 3.318, RMSEA = 0.068, GFI = 0.856, IFI = 0.951, NFI = 0.872, CFI = 0.931, and TLI = 0.925. The overall fit of this model is not yet up to standard. Wu [76] pointed out that when a researcher proposes a hypothetical model based on a literature analysis or a rule of thumb, and it fails to fit the observed data by the goodness-of-fit test, the model must be revised. In this study, the MI coefficient method was used to correct the model to conform to the multivariate normal model fit and parameter calculation. The corrected values are shown in Table 4, x2/DF = 2.482, RMSEA = 0.049, GFI = 0.901, IFI = 0.956, NFI = 0.936, CFI = 0.955, and TLI= 0.956. All parameters met the standard requirements to complete the SEM path test and parameter calculation.

Table 4.

Model fitting indicators.

5.4. Test of the Hypothetical Path

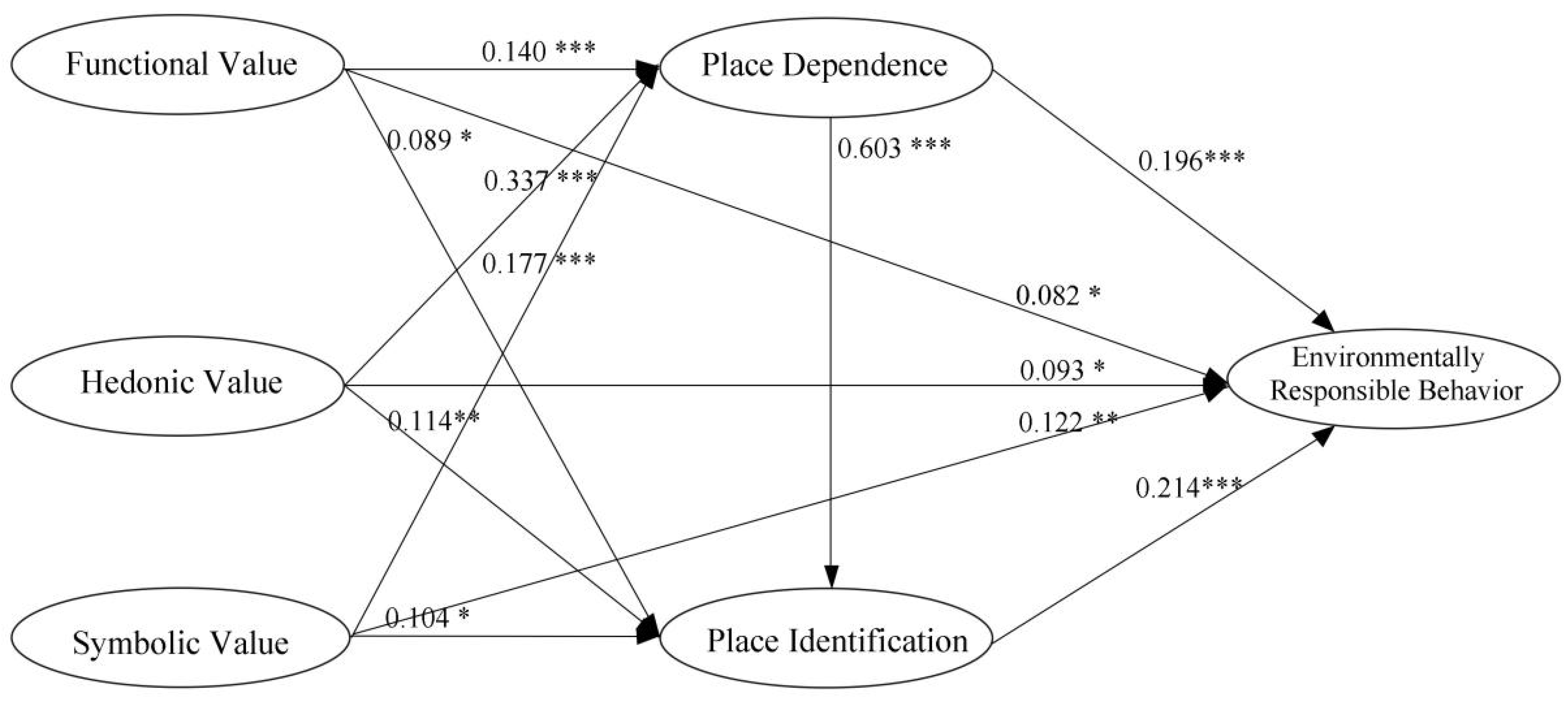

A hypothetical path analysis was performed with significant p < 0.05 as the test criterion, and the test results of the SEM are shown in Table 5. Based on the results of the data analysis, the path coefficient diagram was plotted (Figure 2). Hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, and H6 are valid. The functional value (path coefficient = 0.140), hedonic value (path coefficient = 0.337), and symbolic value (path coefficient = 0.177) in the forest health tourism’s experiential value have a significant positive effect on place dependence. The functional value (path coefficient = 0.089), hedonic value (path coefficient = 0.114), and symbolic value (path coefficient = 0.104) of the forest health tourism’s experiential value have a significant positive effect on place identification. Hypotheses H7, H8, and H9 are valid. Place dependence (path coefficient = 0.196) has a significant positive effect on ERB, place identification (path coefficient = 0.214) has a significant positive effect on ERB, and place dependence (path coefficient = 0.603) has a significant positive effect on place identification. Hypotheses H10, H11, and H12 are valid. The functional value (path coefficient = 0.082), hedonic value (path coefficient = 0.093), and symbolic value (path coefficient = 0.122) have a significant positive effect on ERB.

Table 5.

Model hypothesis testing.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural equation model (NOTE: ***, ** and * indicate p is significant at 0.001, 0.01 and 0.05 levels of significance, respectively).

5.5. Mediation Effects of Place Attachment

The analysis of the effect of place attachment is shown in Table 6 and Table 7. The indirect effect of the functional value in the experiential value on ERB was 0.097, and there was a significant positive effect on ERB. It can be seen that place attachment plays a partial mediating effect in the functional value–ERB path [77]. Among them, the upper and lower place values of place attachment in path symbols A–E–F and A–D–E–F do not include 0, and the indirect effect is significant; place identity in path A–D–F has both upper and lower values including 0, and the indirect effect is not significant. At this point, the mediating effect mainly relies on place attachment in its internal two dimensions to play a mediating effect. Place attachment in the model paths, B–D–F, B–E–F, and B–D–E–F, have upper and lower values that do not include 0. The indirect effect is 0.178, with a significance. Meanwhile, there is a significant positive effect of the hedonic value in the experiential value on ERB. It can be seen that place attachment plays a partial mediating effect in the hedonic value–ERB path. Similarly, it can be concluded that place attachment plays a partial mediating effect in the symbolic value–ERB path.

Table 6.

Analysis of the effect of place attachment.

Table 7.

Analysis of the mediating effect of place attachment.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Preliminary Findings

This study explores the influence of the experiential value of forest health tourism on place attachment and ERB, by taking Fuzhou National Park as an example. Among them, the experiential value of forest health tourism can be divided into functional values, the hedonic value and symbolic value, and place attachment is divided into place dependence and place identification. This study provides empirical evidence that the experiential value of forest health tourism and place attachment are the potential influencing variables of ERB [78]. The following conclusions were drawn by testing the model.

6.1.1. Experiential Value of Forest Health Tourism has a Significant Positive Effect on Place Attachment

All elements of the experiential value significantly influence the place attachment of forest health tourism. The degree of influence on place attachment was from high to low in the sequence of the hedonic value > symbolic value > functional value. The degree of influence on place identity in descending order is the hedonic value > symbolic value > functional value. A significant positive effect of tourism’s experiential value on place attachment was demonstrated in a previous study [79], and the present study verified again that this hypothesis is equally valid in forest health tourism situations. In the rapid pace of modern society, people are tired of coping with the pressures of work, social life, and family, and are doing difficult transitions among multiple roles. Therefore, obtaining the hedonic value of greater sensory and emotional comfort through forest health tourism is the primary need of tourists.

6.1.2. Experiential Value of Forest Health Tourism Has a Significant Positive Effect on ERB

All three dimensions of the experiential value of forest health tourism directly influenced ERB; the descending order of influence is the symbolic value > hedonic value > functional value. The results suggest that multidimensional perceptual stimulation can trigger human’s thinking about nature. When the inner perception of the environmental value is stimulated, it will actively reduce the damage to the environment and even regulate the behavior of the surrounding tourists. It is consistent with the findings of Lee and Ives [22,60].

6.1.3. Place Attachment Has a Significant Positive Effect on ERB

Place attachment significantly affects ERB. On the one hand, place attachment can directly influence ERB positively. According to the magnitude of the path coefficients, the standardized path coefficients of place attachment are significantly higher than experiential value, indicating that place attachment has a greater influence on ERB. It is consistent with the findings of Alessa and Chiu [42,44]. On the other hand, place dependence in place attachment directly and significantly affects place identification. Compared to the elements of forest health tourism’s experiential value, place attachment is the most critical factor that affects place identification. This is consistent with Qiu’s findings [16].

6.1.4. Place Attachment Has a Mediating Effect on the Forest Health Tourism Experiential Value-ERB Model

Forest health tourism’s experiential value affects ERB directly and also affects ERB indirectly through place attachment. This is consistent with the findings of Tveit and Palmet [45,56]. This indicates that place attachment plays an important mediating role in the association between the experiential value of forest health tourism and the ERB. Compared to place identification, place attachment has a greater effect on ERB, which can affect ERB directly as well as indirectly through place identification [61]. Therefore, to cultivate ERB comprehensively, managers should not only focus on the system construction of forest health tourism sites, but also take the importance of place attachment into adequate consideration.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study applied the experiential value to the study of factors and mechanisms affecting the tourists’ intention for practicing ERB in forest health tourism. It complements the existing empirical studies on the factors and mechanisms affecting the intention of ERB, [80] and expands the scope of the application.

First, with model testing, we reveal the mechanism by which forest health tourism’s experiential value affects ERB. In addition, we found that forest health tourism’s experiential value can be an antecedent variable of place attachment and ERB. These findings provide an empirical basis for analyzing the complex realization path of “forest health tourism experiential value → place attachment → ERB”.

Second, we found that place attachment is a more important element driving the ERB than the other element of the forest health tourism’s experiential value. Compared to place identification, place attachment had a greater impact on ERB. This emphasizes the importance of place attachment in affecting ERB.

Finally, the effects of the forest health tourism’s experiential value and place attachment on ERB were analyzed, which validates the effects of place attachment on ERB and enriches the study of it again. At the same time, the importance of the experiential value and place attachment in forest health tourism in explaining and predicting individual behavior is demonstrated.

6.3. Management Recommendations

6.3.1. Strengthen Policy and Institutional Support

On the one hand, national policy is an important guarantee for the orderly and steady progress of the forest health tourism industry. To foster the awareness of ERB through national policies, it is required that relevant management regulations covering environmental protection should be established at local levels, so as to guide the ERB better. For example, China and South Korea signed the Memorandum of Understanding between China and South Korea on Forest Well-being Cooperation in 2015 [81], which caused a boom in the construction of recreational bases in China. The Forestry Bureau of Sichuan Province in China realized the importance of guiding ERB in advance and set up the relevant reward and punishment regulations to regulate tourists’ behavior as a response to the national policy. On the other hand, based on foreign governance regulations, China’s Fujian Province has successively issued the “Rules for Forest Recreation Base Assessment Criteria in Fujian Province” and “Rules for Forest Recreation Town Assessment Criteria in Fujian Province (for Trial Implementation)”, which provide policy guarantees for the system construction and industrial base selection for the development of forest health tourism. At the same time, management assessment standards have been added to promote the healthy development of forest tourism industry. These national policies and local regulations have produced good results in cultivating behavioral habits and guiding tourists to carry out ERB.

6.3.2. Enhance the Functional Value of Forest Health Tourism

The functional value of forest health tourism is to meet the most basic needs of travel. It includes the traffic network outside the scenic spot, the planning layout inside the scenic spot, basic service facilities, safety facilities, and so on. Since most of the forest health sites are located in the suburbs, away from the noise of the city, transportation becomes a key issue to travel. Therefore, as for external transportation, managers can maintain a good communication with local transportation authorities to ensure the accessibility of travel. As for the internal facilities of the scenic spot, it is necessary to develop more entertainment and leisure projects (such as forest walks and forest concerts), medical and pension facilities (such as health self-assessment huts and recreation stations), and science education sites (such as forest study bases and five-sense science experience stations) to meet the needs of people of different ages, while satisfying the basic services. At the same time, professional forest health talents should be cultivated to provide visitors with an ecological trip.

6.3.3. Fully Satisfy the Hedonic Value of Forest Health Tourism

A healthy forest environment is considered to be an effective way to relieve people’s stress and enhance their health benefits [63]. Studies have shown that to meet the effective emotional supply of tourists, managers should reasonably design recreation activity products, plan recreation routes, and actively intervene in the emotional state of tourists to finally achieve the unity of emotions and environment so that tourists can achieve a happy feeling and have a pleasant experience [82]. On the one hand, the forest health industry cannot rely on forestry or tourism alone; it also needs to focus on the integration of various industries such as services, photography, medical care, transportation, and science popularization. Various activities related to nature and ecology can be carried out, such as large bird-watching exhibitions and forest health photography competitions, to mobilize participants and attract tourists to visit and learn, and further promote forest health tourism. On the other hand. The managers should also pay special attention to the creation of a “healthy and pollution-free” atmosphere, optimize the recreation environment, and explore the diversity of forest’s ecological functions. It is important to enhance the spiritual vitality of tourists to increase their place dependence and stimulate their ERB. Forest health tourism should be given the dual attributes of scenic and environmental protection.

6.3.4. Strengthen the Symbolic Value of Forest Health Tourism

The results show that the symbolic value of the experiential value has the greatest impact on ERB, which means that “brand impressions” is important for the forest health tourism. To ensure the maximum promotion of the forest health tourism industry, a combination of the traditional promotion methods and modern internet platforms should be used. The short video boom can be used to improve the access to information for consumers, and to enhance the health concept of forest health recreation by integrating forest recreation into daily life. At the same time, it is also possible to create a small story of its own for each forest recreation base to create an exclusive IP and strengthen viewers’ memory, thus expanding the influence of the forest recreation industry and forming a forest health tourism industry with brand characteristics, thereby enhancing public awareness of environmental protection.

6.4. Limitations

There are some limitations in this study. First, the object of the study is Fuzhou National Forest Park, and it is necessary to expand the sample for testing the generalizability and validity of the research conclusions in further studies. Second, the data in the research are mainly cross-sectional data, and the data type of the study is relatively single. Further studies can adopt a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal data to enhance the reliability and credibility of the studies. Finally, when analyzing the effect of the experiential values on ERB, the variability of individual characteristic factors, such as different ages, different occupations, and different levels of education, were not included. In this way, differentiated strategies can be developed to guide the ERB for different types of groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X., X.L. and F.L.; data curation, H.X., X.L., F.L. and X.W.; data analysis, H.X. and F.L.; funding acquisition, M.W.; investigation, H.X., X.L. and X.W.; methodology, H.X. and X.L.; project administration, M.W.; software, H.X. and F.L.; supervision, M.W.; writing—original draft, H.X.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by (1) Special Project of Wuyishan National Park Research Institute, grant number KJG20009A; (2) Forest Park Engineering Technology Research Center of State Forestry Administration, grant number PTJH15002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All figures and tables in the text were drawn by the author. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guo, Y.; Wei, H.; Yuan, X. Ten challenges facing China’s entry into an urban society. Zhongzhou J. 2013, 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, H.; Zhang, G. The impact of population aging on the high-quality development of tourism in China and its spatial effects. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2022, 38, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): A systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Yang, C.-C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; Stanis, S.A.W.; Schneider, I.E.; Heisey, J.J. Crowding and experience-use history: A study of the moderating effect of place attachment among water-based recreationists. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.E.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Cao, M. Examining the Antecedents of Environmentally Responsible Behaviour: Relationships among Service Quality, Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Zhu, L. Behavioral efficacy, human-place emotion and tourists’ willingness to behave responsibly in the environment: An improved model based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 44, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oriade, A.; Schofield, P. An examination of the role of service quality and perceived value in visitor attraction experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Morgan, N.A. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T.; Feng, S. Authenticity: The Link Between Destination Image and Place Attachment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-K. Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: The case of the Korean DMZ. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier Blancas, F.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Caballero, R. A dynamic sustainable tourism evaluation using multiple benchmarks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a Psychology of Being, 3rd ed.; John Wiley Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Qiu, H.; Wu, X. Tourism Place Imagery, Place Attachment and Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Case of Zhejiang Province Tourism Resort. J. Tour. 2014, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H. Tourism Festival Imagery, Festival Attachment, Festival Visitors’ Environmentally Responsible Attitudes and Behaviors —A Case Study of Hangzhou Xixi Flower Festival. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2017, 84–93+117+158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. A Study on the Relationship between Ecotourism Involvement, Local Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Van Der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating Effects of Place Attachment and Satisfaction on the Relationship between Tourists’ Emotions and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, D.X.; Li, S.Y.; Li, W.M. Moderating effect of place attachment on pro-environmental behavior of forest tourism tourists. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 40, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Shen, Y.L. The influence of leisure involvement and place attachment on destination loyalty: Evidence from recreationists walking their dogs in urban parks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Fan, J.; Zhao, L. Development of the Academic Study of Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Literature Review. J. Tour. 2018, 33, 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W.H.; Woo, J.-M.; Ryu, J.S. Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers’ stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag-Ostrom, E.; Stenlund, T.; Nordin, M.; Lundell, Y.; Ahlgren, C.; Fjellman-Wiklund, A.; Jarvholm, L.S.; Dolling, A. “Nature’s effect on my mind”—Patients’ qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Qiao, Y. Exploring the construction of forest recreation base. For. Resour. Manag. 2017, 93–96+156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; He, W.; Zhang, W.; Yan, W. Exploration on the development of forest recreation industry based on national forest park--Sichuan Kongshan National Forest Park as an example. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2016, 37, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Liu, B. An analysis of forest tourism resources development ideas in the new era. West. For. Sci. 2020, 49, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, J. Research on the integration of forest tourism and ecotourism—a review of “Forest Environmental Resources and Forest Tourism Product Development—Theory and Practice”. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Hanavan, R.P.; Kamoske, A.G.; Schaaf, A.N.; Eager, T.; Fisk, H.; Ellenwood, J.; Warren, K.; Asaro, C.; Vanderbilt, B.; Hutten, K.; et al. Supplementing the Forest Health National Aerial Survey Program with Remote Sensing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned from a Collaborative Approach. J. For. 2022, 120, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Pandey, A.C. Spectral aspects for monitoring forest health in extreme season using multispectral imagery. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2021, 24, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Mendes, J.; Patrícia, V. Conceptualizing the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.R.; Okumus, F.; Wang, Y.; Kwun, D.J.-W. An epistemological view of consumer experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, G. A study of traditional festival experience from a symbolic perspective: The example of Guangzhou Spring Festival Flower Market. Decoration 2019, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M. Research on the Experience Value of Destination Imagery Perception from the Perspective of Human-Land Relationship. D Northeast. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2019, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R. Testing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment in Recreational Settings. Environ. Behav 2005, 37, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Tang, P.; Jiang, L.; Su, M.M. Influencing mechanism of tourist social responsibility awareness on environmentally responsible behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Gong, J.; Tong, Q.; Zhang, T.i; Li, W. A study on the community governance model of Mount Lu in the context of national park construction—A perspective based on residents’ local attachment. Geogr. Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 104–109, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Alessa, L.; Bennett, S.M.; Kliskey, A.D. Effects of knowledge, personal attribution and perception of ecosystem health on depreciative behaviors in the intertidal zone of Pacific Rim National Park and Reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, D.J.; Hungerford, H. Predictors of Responsible Behavior in Members of Three Wisconsin Conservation Organizations. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-T.H.; Lee, W.-I.; Chen, T.-H. Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Ecotourism: Exploring the Role of Destination Image and Value Perception. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, A.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.F. Using spatial metrics to predict scenic perception in a changing landscape: Dennis, Massachusetts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, Z. Research on tourism experience and well-being of forest recreationists: A case study of Hunan Tianjiling National Forest Park. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 11, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G.N. VALUE, SATISFACTION AND BEHAVIORAL INTENTIONS IN AN ADVENTURE TOURISM CONTEXT. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middel, A.; Krayenhoff, E.S. Micrometeorological determinants of pedestrian thermal exposure during record-breaking heat in Tempe, Arizona: Introducing the MaRTy observational platform. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Zhao, X.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J. Influence of environmental education perceptions on tourists’ implementation of environmentally responsible behaviors—Based on SOR theory perspective. J. Chongqing Univ. Commer. Ind. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Na, M.; Xie, Y.; Gursoy, D. Tourism destination experience value: Dimensional identification, scale development and validation. J. Tour. 2019, 34, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerhall, C.M.; Purcell, T.; Taylor, R. Fractal dimension of landscape silhouette outlines as a predictor of landscape preference. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.L. Exploring the effects of environmental experience on attachment to urban natural areas. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.S.Y.; Ma, A.T.H.; Wong, G.K.L.; Lam, T.W.L.; Cheung, L.T.O. The Impacts of Place Attachment on Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention and Satisfaction of Chinese Nature-Based Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D. Achieving Environmentally Responsible Behavior for Tourists and Residents: A Norm Activation Theory Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-M.; Jung, T.Y. An Analysis on the Attitudes of Local Residents to the Mountainous Ecology Trail Development Plan—Focusing on Sobaeksan Jarackgil. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2013, 41, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, C.-K. The moderating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival quality and behavioral intentions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place Attachment and Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The relations between natural and civic place attachment and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Kendal, D. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Fu, W.; Hong, S.; Dong, J.W.; Wang, M. A study on the relationship between landscape perception and the environmental responsibility behavior of park recreationists: A case study of mountain parks in Fuzhou City. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyem, J. Outdoor recreation and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour.-Res. Plan. Manag. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. A Conceptual Framework for Leisure and Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2009, 10, 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The Self-Regulation of Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Research on Visitor Loyalty Model of Ancient Villages-Based on the Perspective of Visitor Perceived Value and Its Dimensions. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. Tourism Experience Research. D Northeast. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2005, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.Y. The Effects of Ancient Village Residents’ Place Attachment on Their Relocation Willingness Under the Background of Tourism Development:A Case Study of Wuyuan Ancient Villages. Econ. Manag. J. 2014, 5, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Middel, A.; Haeb, K.; Brazel, A.J.; Martin, C.A.; Guhathakurta, S. Impact of urban form and design on mid-afternoon microclimate in Phoenix Local Climate Zones. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakinyo, T.E.; Kong, L.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Yuan, C.; Ng, E. A study on the impact of shadow-cast and tree species on in-canyon and neighborhood’s thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2017, 115, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, F.; Zhou, X. A study on the relationship between environmental preferences and environmental restorative perceptions in the context of mountain landscape. Outdoor Recreat. Res. 2008, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Steeneveld, G.J.; Koopmans, S.; Heusinkveld, B.G.; Theeuwes, N.E. Refreshing the role of open water surfaces on mitigating the maximum urban heat island effect. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; Tan, C.L.; Nindyani, A.; Jusuf, S.K.; Tan, E. Influence of Water Bodies on Outdoor Air Temperature in Hot and Humid Climate. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Design & Construction, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 7–9 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. Ecological city and urban sustainable development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Green Buildings and Sustainable Cities (GBSC), Bologna, Italy, 15–16 September 2011; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, C. Hedonic and Utilitarian Motivations of Social Network Site Usage; Springer Books: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Structural Equation Modeling:Operations and Applications of AMOS, 2nd ed.; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.J. An assessment of environmental literacy and analysis of predictors of responsible environmental behavior held by secondary teachers in Hualien County of Taiwan. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, A.E. Promoting Healhy Food Choices in Early Childhood: An Ecological Approach; Royal Roads University: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-T.; Hsu, H.; Chen, C.-C. An examination of experiential quality, nostalgia, place attachment and behavioral intentions of hospitality customers. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Roesler, J. Wind direction and cool surface strategies on microscale urban heat island. Urban Clim. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S. The Structural Relationships between Perceived Restorative Environment and Positive Emotion, Psychological Happiness, and Quality of Life: Focused on Attention Restoration Theory. Tour. Res. 2020, 45, 135–159. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).