Secondary Metabolites Produced by Trees and Fungi: Achievements So Far and Challenges Remaining

Abstract

1. Introduction

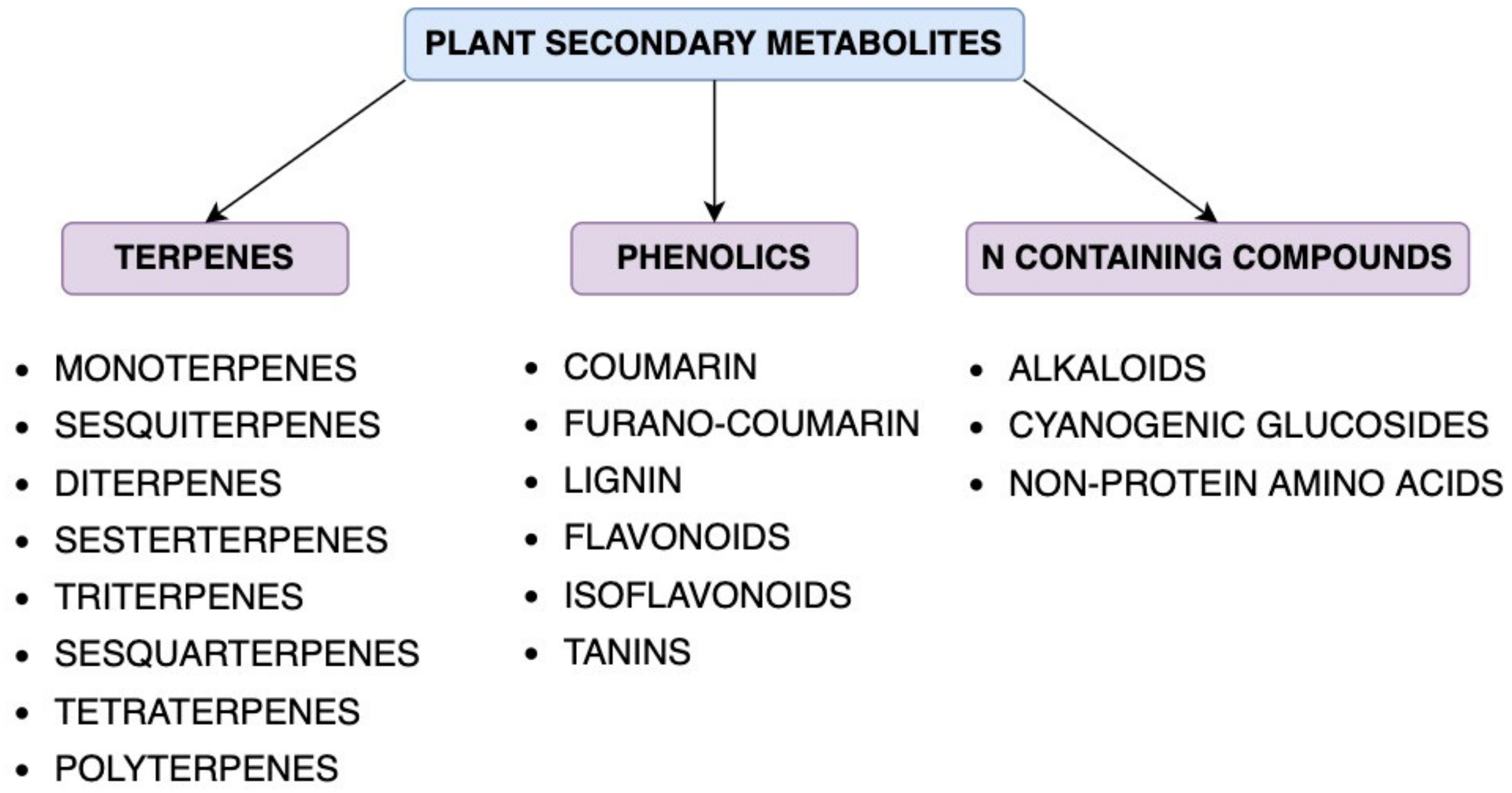

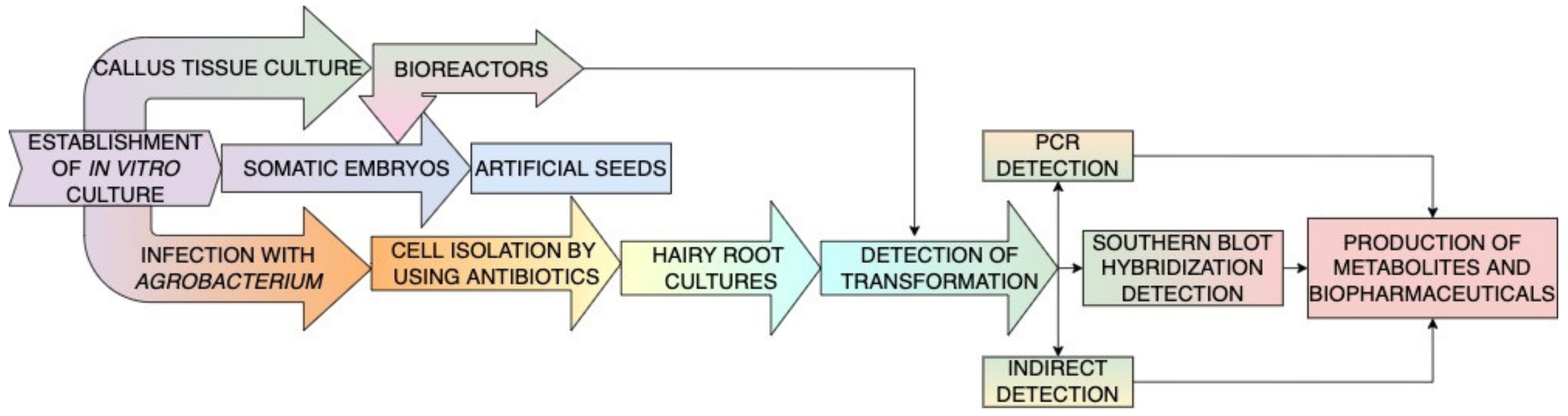

2. Main Groups of Secondary Metabolites and Their Characteristics

3. Secondary Metabolite Extraction Methods from Plant or Fungal Tissues

Examples of Research Protocols Used to Detect and Quantify the Secondary Metabolites Using Key Analytical Methods

4. Applications of Secondary Metabolites Occurring in Trees and Fungi

4.1. Forest Trees as a Source of Various Secondary Metabolites

4.2. Secondary Metabolites Naturally Occurring in Conifers

4.3. Secondary Metabolites Naturally Occurring in Angiosperm Trees

4.4. Secondary Metabolites Naturally Occurring in Fungi

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Twaij, B.M.; Hasan, M.N. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Plant Sources: Types, Synthesis, and Their Therapeutic Uses. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2022, 13, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, E.P.; Borowska, A. Biologia; Multico: Warszawa, Poland, 2000; ISBN 978-83-7073-090-1. [Google Scholar]

- Welte, M.A.; Gould, A.P. Lipid Droplet Functions beyond Energy Storage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopcewicz, J.; Szmidt-Jaworska, A. Fizjologia Roślin; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-01-21278-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, K.S.; Lister, C. Flavonoid Functions in Plants. In Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Applications; Andersen, Ø.M., Markham, K.R., Eds.; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 397–443. ISBN 978-0-8493-2021-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein, D.J. Secondary Metabolites and Plant/Environment Interactions: A View through Arabidopsis Thaliana Tinged Glasses. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdeo, A. Plant Cell Elicitation for Production of Secondary Metabolites: A Review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2007, 1, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Barbulova, A.; Colucci, G.; Apone, F. New Trends in Cosmetics: By-Products of Plant Origin and Their Potential Use as Cosmetic Active Ingredients. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Wightman, E.L. Herbal Extracts and Phytochemicals: Plant Secondary Metabolites and the Enhancement of Human Brain Function. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboulsi, I.; Aboulmouhajir, A.; Kouisni, L.; Bekkaoui, F.; Yasri, A. Plants Extracts and Secondary Metabolites, Their Extraction Methods and Use in Agriculture for Controlling Crop Stresses and Improving Productivity: A Review. Acad. J. Med. Plants 2018, 6, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B. Classes and Functions of Secondary Products from Plants. In Chemicals from Plants: Perspectives on Plant Secondary Products; Walton, N.J., Brown, D.E., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-981-02-2773-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Fernie, A.R.; Luo, J. Exploring the Diversity of Plant Metabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koal, T.; Deigner, H.-P. Challenges in Mass Spectrometry Based Targeted Metabolomics. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010, 10, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.-J.; Xiao, J.-H. Secondary Metabolites from Higher Fungi: Discovery, Bioactivity, and Bioproduction. In Biotechnology in China I; Zhong, J.-J., Bai, F.-W., Zhang, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 79–150. ISBN 978-3-540-88414-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M.E.; Davis, B.; Phillips, M.A. Medically Useful Plant Terpenoids: Biosynthesis, Occurrence, and Mechanism of Action. Molecules 2019, 24, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; Schwender, J.; Zeidler, J.; Lichtenthaler, H.K. Properties and Inhibition of the First Two Enzymes of the Non-Mevalonate Pathway of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2000, 28, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.W.; Alonso-Gutierrez, J.; Keasling, J.D.; Lee, T.S. Isoprenoid Drugs, Biofuels, and Chemicals—Artemisinin, Farnesene, and Beyond. In Biotechnology of Isoprenoids; Schrader, J., Bohlmann, J., Eds.; Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 148, pp. 355–389. ISBN 978-3-319-20106-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, R.; Schmidt, A.; Peters, R.J. Isoprenyl Diphosphate Synthases: The Chain Length Determining Step in Terpene Biosynthesis. Planta 2019, 249, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncan, D.; Tsang, S.; Li, C.; Lee, I.; Lam, H.-M.; Chan, T.-F.; Hui, J. Terpenes and Terpenoids in Plants: Interactions with Environment and Insects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.T. Diterpenes and Their Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents. Phytother. Res. PTR 2017, 31, 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Hernández-Carlos, B.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C. Shikimic Acid Pathway in Biosynthesis of Phenolic Compounds. In Plant Physiological Aspects of Phenolic Compounds; Soto-Hernández, M., García-Mateos, R., Palma-Tenango, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-033-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik, C.; Nawrot-Chorabik, K.; Woodward, S. Phenolic Compound Concentrations in Picea abies Wood as an Indicator of Susceptibility towards Root Pathogens. For. Pathol. 2020, 50, e12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sova, M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Cinnamic Acid Derivatives. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Constabel, C.P. MYB Repressors as Regulators of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C.; Amo, A.; Ahmed, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Phenylpropanoid Pathway Engineering: An Emerging Approach towards Plant Defense. Pathogens 2020, 9, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.G. From Lignins to Tannins: Forty Years of Enzyme Studies on the Biosynthesis of Phenolic Compounds. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 3018–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, H.; Rosa, H.; Sobucki, W. Dogarbowywanie i Natłuszczanie Skórzanych Opraw Książek. Ochr. Zabyt. 1998, 4, 386–395. [Google Scholar]

- China, C.; Maguta, M.M.; Nyandoro, S.S.; Hilonga, A.; Kanth, S.V.; Njau, K.N. Alternative Tanning Technologies and Their Suitability in Curbing Environmental Pollution from the Leather Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlikowska, T. Jak Powstają Barwy i Zapachy Kwiatów. Zesz. Probl. Postępów Nauk Rol. 2005, 504, 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent Advances on the Roles of Flavonoids as Plant Protective Molecules after UV and High Light Exposure. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchfield, A.S.; McIntosh, C.A. Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology of Plant Natural Products—A Minireview. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 24, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszek, P.; Weston, L.A.; Ciacka, K.; Krasuska, U.; Gniazdowska, A. L-Canavanine: How Does a Simple Non-Protein Amino Acid Inhibit Cellular Function in a Diverse Living System? Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnen-Johannsen, K.; Kayser, O. Tropane Alkaloids: Chemistry, Pharmacology, Biosynthesis and Production. Molecules 2019, 24, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballhorn, D.J. Cyanogenic Glycosides in Nuts and Seeds. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 129–136. ISBN 978-0-12-375688-6. [Google Scholar]

- Oliviero, T.; Verkerk, R.; Dekker, M. Isothiocyanates from Brassica Vegetables-Effects of Processing, Cooking, Mastication, and Digestion. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1701069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.-H.; Kumar, A.; Imani, J. Plant Cell and Tissue Culture—A Tool in Biotechnology: Basics and Application; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; ISBN 978-3-030-49096-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Wieczfinska, J.; Skała, E.; Śliwiński, T.; Sitarek, P. Transgenesis as a Tool for the Efficient Production of Selected Secondary Metabolites from Plant in Vitro Cultures. Plants 2020, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Chorabik, K.; Pietrzykowski, M. Ecophysiological Aspects of in Vitro Biotechnological Studies Using Somatic Embryogenesis of Callus Tissue toward Protecting Forest Ecosystems. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, M.; Cardoso, F. Advances and Challenges on the in Vitro Production of Secondary Metabolites from Medicinal Plants. Hortic. Bras. 2019, 37, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, S. A Review on Trends in Production of Secondary Metabolites from Higher Plants by In Vitro Tissue, Organ and Cell Cultures. J. Med. Plants Res. 2009, 3, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevón, N.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.-M. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Transformation: Root Cultures as a Source of Alkaloids. Planta Med. 2002, 68, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, M.; Sarkar, S.; Jha, S. Elicitation: A Biotechnological Tool for Enhanced Production of Secondary Metabolites in Hairy Root Cultures. Eng. Life Sci. 2019, 19, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Estrada, K.; Vidal-Limon, H.; Hidalgo, D.; Moyano, E.; Golenioswki, M.; Cusidó, R.; Palazon, J. Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories. Molecules 2016, 21, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shasmita; Singh, N.R.; Rath, S.K.; Behera, S.; Naik, S.K. In Vitro Secondary Metabolite Production Through Fungal Elicitation: An Approach for Sustainability. In Fungal Nanobionics: Principles and Applications; Prasad, R., Kumar, V., Kumar, M., Wang, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 215–242. ISBN 978-981-10-8665-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Kastell, A.; Knorr, D.; Smetanska, I. Exudation: An Expanding Technique for Continuous Production and Release of Secondary Metabolites from Plant Cell Suspension and Hairy Root Cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgaud, F.; Gravot, A.; Milesi, S.; Gontier, E. Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites: A Historical Perspective. Plant Sci. 2001, 161, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehzari, M.; Naghavi, M.R. Phyto-MiRNAs-Based Regulation of Metabolites Biosynthesis in Medicinal Plants. Gene 2019, 682, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.P.; Kinghorn, A.D. Extraction of Plant Secondary Metabolites. In Natural Products Isolation; Sarker, S.D., Nahar, L., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 864, pp. 341–366. ISBN 978-1-61779-623-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan, S.; Chen, Y.; Saravanan, D.; Sundram, K.M.; Yoga Latha, L. Extraction, Isolation and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds from Plants’ Extracts. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelo, A.; Geronimo, R.M.; Vicente, C.J.B.; Callanta, R.B.P.; Bennett, R.M.; Ysrael, M.C.; Dedeles, G.R. TLC Screening Profile of Secondary Metabolites and Biological Activities of Salisapilia tartarea S1YP1 Isolated from Philippine Mangroves. J. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, G. Analysis of Secondary Metabolites from Plant Endophytic Fungi. In Plant Pathogenic Fungi and Oomycetes; Ma, W., Wolpert, T., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1848, pp. 25–38. ISBN 978-1-4939-8723-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot-Chorabik, K.; Marcol-Rumak, N.; Latowski, D. Investigation of the Biocontrol Potential of Two Ash Endophytes against Hymenoscyphus Fraxineus Using In Vitro Plant-Fungus Dual Cultures. Forests 2021, 12, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, M.; Damjanović, A.; Stanojković, T.P.; Đorđević, I.; Tešević, V.; Milosavljević, S.; Gođevac, D. Integration of Dry-Column Flash Chromatography with NMR and FTIR Metabolomics to Reveal Cytotoxic Metabolites from Amphoricarpos Autariatus. Talanta 2020, 206, 120248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younessi-Hamzekhanlu, M.; Ozturk, M.; Jafarpour, P.; Mahna, N. Exploitation of next Generation Sequencing Technologies for Unraveling Metabolic Pathways in Medicinal Plants: A Concise Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178, 114669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesami, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Jones, A.M.P.; Torkamaneh, D. Machine Learning: Its Challenges and Opportunities in Plant System Biology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3507–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinowski, H. Strategie Obronne Roślin Drzewiastych Przed Szkodliwymi Owadami. Śne Pr. Badaw. 2008, 69, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho-Knapik, D.; Sanz, M.Á.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Niinemets, Ü.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Changes of Secondary Metabolites in Pinus Sylvestris L. Needles under Increasing Soil Water Deficit. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teskey, R.O.; Bongarten, B.C.; Cregg, B.M.; Dougherty, P.M.; Hennessey, T.C. Physiology and Genetics of Tree Growth Response to Moisture and Temperature Stress: An Examination of the Characteristics of Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.). Tree Physiol. 1987, 3, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almirall, M.; Montaña, J.; Escribano, E.; Obach, R.; Berrozpe, J.D. Effect of D-Limonene, Alpha-Pinene and Cineole on in Vitro Transdermal Human Skin Penetration of Chlorpromazine and Haloperidol. Arzneimittelforschung 1996, 46, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Kumar Jugran, A.; Jayaweera, S.L.D.; Dias, D.; Sharopov, F.; Taheri, Y.; Martins, N.; Baghalpour, N.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene: A Miracle Gift of Nature. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganyi, M.C.; Regnier, T.; Kumar, A.; Bezuidenhout, C.C.; Ateba, C.N. Biodiversity and Antibacterial Screening of Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Pelargonium Sidoides. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 116, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateba, J.; Toghueo, R.; Awantu, A.; Mba’ning, B.; Gohlke, S.; Sahal, D.; Rodrigues-Filho, E.; Tsamo, E.; Boyom, F.; Sewald, N.; et al. Antiplasmodial Properties and Cytotoxicity of Endophytic Fungi from Symphonia globulifera (Clusiaceae). J. Fungi 2018, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, E.E.; Franco, O.L.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antibiotic Adjuvants: Diverse Strategies for Controlling Drug-Resistant Pathogens. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 85, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, S.; Das, G.; Sen, S.K.; Shin, H.-S.; Patra, J.K. Endophytes: A Treasure House of Bioactive Compounds of Medicinal Importance. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbanpour, M.; Omidvari, M.; Abbaszadeh-Dahaji, P.; Omidvar, R.; Kariman, K. Mechanisms Underlying the Protective Effects of Beneficial Fungi against Plant Diseases. Biol. Control 2018, 117, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Tu, R.; Mei, X.; Wu, S.; Lan, B.; Zhang, L.; Luo, X.; Liu, J.; Luo, M. A Mycophenolic Acid Derivative from the Fungus Penicillium sp. SCSIO Sof101. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Khan, M.A.; Karam, K.; Ullah, N.; Mashwani, Z.-R.; Nadhman, A. Plant in Vitro Culture Technologies; A Promise Into Factories of Secondary Metabolites Against COVID-19. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 610194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.D.; Cox, B.; Waigh, R.D. Natural Products as Leads for New Pharmaceuticals. In Burger’s Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 847–900. ISBN 978-0-470-27815-4. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C. Coronavirus Puts Drug Repurposing on the Fast Track. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, C.A.; Rolain, J.-M.; Colson, P.; Raoult, D. New Insights on the Antiviral Effects of Chloroquine against Coronavirus: What to Expect for COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Wu, S.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Hsiang, C. Emodin Blocks the SARS Coronavirus Spike Protein and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Interaction. Antivir. Res. 2007, 74, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, M. Potential of DNA Intercalating Alkaloids and Other Plant Secondary Metabolites against SARS-CoV-2 Causing COVID-19. Diversity 2020, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicach, S.R.; Chludil, H.D. Plant Secondary Metabolites: Structure—Activity Relationships in Human Health Prevention and Treatment of Common Diseases. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 42, pp. 267–304. ISBN 978-0-444-63281-4. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Liu, R.H. Phytochemicals of Apple Peels: Isolation, Structure Elucidation, and Their Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9905–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyson, D.A. A Comprehensive Review of Apples and Apple Components and Their Relationship to Human Health. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Beta-Lactams and Their Potential Use as Novel Anticancer Chemotherapeutics Drugs. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishnav, P.; Demain, A.L. Unexpected Applications of Secondary Metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forloni, G.; Iussich, S.; Awan, T.; Colombo, L.; Angeretti, N.; Girola, L.; Bertani, I.; Poli, G.; Caramelli, M.; Grazia Bruzzone, M.; et al. Tetracyclines Affect Prion Infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10849–10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, P. Federal Disease Control--Scrapie. Can. Vet. J. Rev. Vet. Can. 2002, 43, 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Llorens, F.; Zarranz, J.-J.; Fischer, A.; Zerr, I.; Ferrer, I. Fatal Familial Insomnia: Clinical Aspects and Molecular Alterations. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2017, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, K.J.; Correll, C.M. Prion Disease. Semin. Neurol. 2019, 39, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruheim, P.; Borgos, S.E.F.; Tsan, P.; Sletta, H.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Lancelin, J.-M.; Zotchev, S.B. Chemical Diversity of Polyene Macrolides Produced by Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 and Recombinant Strain ERD44 with Genetically Altered Polyketide Synthase NysC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4120–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, M.; Luo, H. Statins for Multiple Sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 12, CD008386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntolkeras, G.; Barba, C.; Mavropoulos, A.; Vasileiadis, G.K.; Dardiotis, E.; Sakkas, L.I.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Bogdanos, D.P. On the Immunoregulatory Role of Statins in Multiple Sclerosis: The Effects on Th17 Cells. Immunol. Res. 2019, 67, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisse, M.; Mucke, L. A Prion Protein Connection. Nature 2009, 457, 1090–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavigan, C.S.; Kiely, S.P.; Hirtzlin, J.; Bell, A. Cyclosporin-Binding Proteins of Plasmodium Falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 2003, 33, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leneghan, D.; Bell, A. Immunophilin-Protein Interactions in Plasmodium Falciparum. Parasitology 2015, 142, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holopainen, J.K.; Virjamo, V.; Ghimire, R.P.; Blande, J.D.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Kivimäenpää, M. Climate Change Effects on Secondary Compounds of Forest Trees in the Northern Hemisphere. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Sood, P. On the Emergence, Spread and Resistance of Candida Auris: Host, Pathogen and Environmental Tipping Points. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlen, K.L.; Aschehoug, E.T.; Callaway, R.M. Plant Behavioural Ecology: Dynamic Plasticity in Secondary Metabolites. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, T.; Hilszczański, J. The Effect of Temperature and Humidity Changes on Insects Development Their Impact on Forest Ecosystems in the Expected Climate Change. For. Res. Pap. 2013, 74, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.A.; Nita, M.; De Wolf, E.D.; Esker, P.D.; Gomez-Montano, L.; Sparks, A.H. Plant Pathogens as Indicators of Climate Change. In Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 499–513. ISBN 978-0-12-821575-3. [Google Scholar]

- Netherer, S.; Schopf, A. Potential Effects of Climate Change on Insect Herbivores in European Forests—General Aspects and the Pine Processionary Moth as Specific Example. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, A.; Caffarra, A.; Kelleher, C.; O’Neill, B.; Diskin, E.; Pletsers, A.; Proctor, H.; Stirnemann, R.; O’Halloran, J.; Peñuelas, J.; et al. Surviving in a Warmer World: Environmental and Genetic Responses. Clim. Res. 2012, 53, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, M.; Hanafi, M.M.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Akmar, A.S.N.; Azizi, P.; Idris, A.S.; Taheri, S.; Foroughi, M. Profiling Secondary Metabolites of Plant Defence Mechanisms and Oil Palm in Response to Ganoderma Boninense Attack. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 122, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.L.; Madden, L.V. Introduction to Plant Disease Epidemiology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-471-83236-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante, P.; Genre, A. Mechanisms Underlying Beneficial Plant-Fungus Interactions in Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-12-370526-6. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, R.D. Ecological Aspects of Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: With Special Emphasis on the Functional Diversity of Interactions Involving the Extraradical Mycelium. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, J.F.; Paul, L.R.; Finlay, R.D. Microbial Interactions in the Mycorrhizosphere and Their Significance for Sustainable Agriculture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaling, M.; Schmidt, A.; Moritz, F.; Rosenkranz, M.; Witting, M.; Kasper, K.; Janz, D.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Polle, A. Mycorrhiza-Triggered Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Networks Impinge on Herbivore Fitness. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2639–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.; Batool, A.; Nasir, F.; Jiang, S.; Mingsen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, H. Mechanistic Insights into Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi-Mediated Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C.; Oldroyd, G.E.D. Plant Signalling in Symbiosis and Immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genre, A.; Lanfranco, L.; Perotto, S.; Bonfante, P. Unique and Common Traits in Mycorrhizal Symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avio, L.; Turrini, A.; Giovannetti, M.; Sbrana, C. Designing the Ideotype Mycorrhizal Symbionts for the Production of Healthy Food. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Suseela, V. Unraveling Arbuscular Mycorrhiza-Induced Changes in Plant Primary and Secondary Metabolome. Metabolites 2020, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolucci, M.; Avio, L.; Palla, M.; Sbrana, C.; Turrini, A.; Giovannetti, M. Health-Promoting Properties of Plant Products: The Role of Mycorrhizal Fungi and Associated Bacteria. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaynab, M.; Fatima, M.; Abbas, S.; Sharif, Y.; Umair, M.; Zafar, M.H.; Bahadar, K. Role of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Defense against Pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb, M.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Plant Secondary Metabolites as Defenses, Regulators, and Primary Metabolites: The Blurred Functional Trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Wu, Z.; Robert, C.A.M.; Ouyang, X.; Züst, T.; Mestrot, A.; Xu, J.; Erb, M. Soil Chemistry Determines Whether Defensive Plant Secondary Metabolites Promote or Suppress Herbivore Growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2109602118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Louie, K.B.; Hao, Z.; Mansoori, N.; da Rocha, U.N.; Shi, S.; Cho, H.; Karaoz, U.; Loqué, D.; Bowen, B.P.; et al. Dynamic Root Exudate Chemistry and Microbial Substrate Preferences Drive Patterns in Rhizosphere Microbial Community Assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y. Linking Plant Secondary Metabolites and Plant Microbiomes: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 621276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, Z.E.; DiBaise, J.K.; Dautel, S.E.; Isern, N.G.; Kim, Y.-M.; Hoyt, D.W.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Brewer, H.M.; Weitz, K.K.; Metz, T.O.; et al. Temporospatial Shifts in the Human Gut Microbiome and Metabolome after Gastric Bypass Surgery. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.T.; Aksenov, A.A.; Nothias, L.F.; Foulds, J.R.; Quinn, R.A.; Badri, M.H.; Swenson, T.L.; Van Goethem, M.W.; Northen, T.R.; Vazquez-Baeza, Y.; et al. Learning Representations of Microbe-Metabolite Interactions. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, S.; Sen, P.; Dickens, A.M.; Orešič, M.; Bertram, H.C. Gut Metabolome Meets Microbiome: A Methodological Perspective to Understand the Relationship between Host and Microbe. Methods 2018, 149, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, H.; Franzosa, E.A.; Mclver, L.J.; Banerjee, S.; Sirota-Madi, A.; Kostic, A.D.; Clish, C.B.; Vlamakis, H.; Xavier, R.J.; Huttenhower, C. Predictive Metabolomic Profiling of Microbial Communities Using Amplicon or Metagenomic Sequences. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, B.B. The Connection and Disconnection Between Microbiome and Metabolome: A Critical Appraisal in Clinical Research. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2020, 22, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dróżdż, P.; Pyrzynska, K. Extracts from Pine and Oak Barks: Phenolics, Minerals and Antioxidant Potential. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 101, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, M. Secondary Metabolites of Ethanol Extracts of Pinus sylvestris Cones from Eastern Anatolia and Their Antioxidant, Cholinesterase and α-Glucosidase Activities. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2019, 14, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaudinova, E.; Mironov, P. Changes of Non-Proteinogenic Amino Acids in Vegetative Organs of Pinus sylvestris. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2016, 52, 773–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Rogoziński, T.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. Phenolic Compounds in Trees and Shrubs of Central Europe. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, A.; Serrilli, A.M.; Vittori, S.; Papa, F.; Maggi, F.; Di Cecco, M.; Ciaschetti, G.; Bruno, M.; Rosselli, S.; Bianco, A. Secondary Metabolites from Pinus mugo TURRA Subsp. Mugo Growing in the Majella National Park (Central Apennines, Italy). Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 2091–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-J.; Fan, F.; Yan, X.-N.; Yu, H.-Y.; Li, G.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.-H.; Si, C.-L. Isolation, Separation, and Structural Elucidation of Secondary Metabolites of Pinus Pumila. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacsu, M.; Eklund, P.C.; Sjöholm, R.E.; Pietarinen, S.P.; Ahotupa, M.O.; Holmbom, B.R.; Willför, S.M. Antioxidant Flavonoids from Knotwood of Jack Pine and European Aspen. Holz Roh Werkst. 2007, 65, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicandri, E.; Covino, S.; Sebastiani, B.; Paolacci, A.R.; Badiani, M.; Sorgonà, A.; Ciaffi, M. Monoterpene Synthase Genes and Monoterpene Profiles in Pinus nigra Subsp. Laricio. Plants 2022, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, K.; Wang, A.; Meng, D.; Li, J.L. Secondary Metabolites from the Fresh Leaves of Pinus yunnanensis Franch. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Bhardwaj, P.; Kaur, S. Medicinal Value of Secondary Metabolites of Pines Grown in Himalayan Region of India. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 15, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, T.; Albert, L.; Németh, L.; Vršanská, M.; Schlosserová, N.; Voběrková, S.; Visi-Rajczi, E. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties of Norway Spruce (Picea abies H. Karst.) and Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrière) Cone Extracts. Forests 2021, 12, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamponi, L.; Michelozzi, M.; Capretti, P. Terpene Response of Picea abies and Abies alba to Infection with Heterobasidion s.l. For. Pathol. 2007, 37, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Bonn, B.; Kreuzwieser, J. Terpenoids Are Transported in the Xylem Sap of Norway Spruce. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1766–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprun, A.R.; Dubrovina, A.S.; Aleynova, O.A.; Kiselev, K.V. The Bark of the Spruce Picea jezoensis Is a Rich Source of Stilbenes. Metabolites 2021, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, L.; Bonetti, A.; D’Acqui, L.; Meneguzzo, F.; Zabini, F. Affordable Production of Antioxidant Aqueous Solutions by Hydrodynamic Cavitation Processing of Silver Fir (Abies alba Mill.) Needles. Foods 2019, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaszewska, M.; Rutkowska, J.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Słupski, J.; Antoniewska, A.; Smoleń, S.; Łukasiewicz, M.; Baranowski, D.; Duda, I.; Pietsch, J. Red Arils of Taxus baccata L.—A New Source of Valuable Fatty Acids and Nutrients. Molecules 2021, 26, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.K.Q.; Lee, B.W.; Nguyen, N.H.; Cho, H.M.; Venkatesan, T.; Doan, T.P.; Kim, E.; Oh, W.K. Antiviral Activities of Compounds Isolated from Pinus densiflora (Pine Tree) against the Influenza A Virus. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontela-Saseta, C.; López-Nicolás, R.; González-Bermúdez, C.A.; Martínez-Graciá, C.; Ros-Berruezo, G. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Fruit Juices Enriched with Pine Bark Extract in an in Vitro Model of Inflamed Human Intestinal Epithelium: The Effect of Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.; Wang, H.; Shen, Y.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Wang, C. Anti-inflammatory Properties of Fermented Pine (Pinus morrisonicola Hay.) Needle on Lipopolysaccharide-induced Inflammation in RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, M.; Sipponen, A.; Peltola, R.; Lohi, J.; Jokinen, J.J.; Papp, A.; Carlson, P.; Sipponen, P. Antibacterial Effects of Home-Made Resin Salve from Norway Spruce (Picea abies). APMIS 2007, 115, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio-Kaila, T.; Kyyhkynen, A.; Rautkari, L.; Siitonen, A. Antibacterial Effects of Extracts of Pinus Sylvestris and Picea Abies against Staphylococcus Aureus, Enterococcus Faecalis, Escherichia Coli, and Streptococcus Pneumoniae. BioResources 2015, 10, 7763–7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.I.; Bohlmann, J. Diterpene Resin Acids in Conifers. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2415–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulusu, N.N.; Ercil, D.; Sakar, M.K.; Tezcan, E.F. Abietic Acid Inhibits Lipoxygenase Activity. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Kunert, O.; Presser, A.; Bauer, R. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Larch (Larix decidua L.) Sawdust. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11688–11693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzika, E.D.; Tassis, P.D.; Papatsiros, V.G.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Siochu, A.; Bauer, R.; Alexopoulos, C.; Kyriakis, S.C.; Franz, C. Evaluation of In-Feed Larch Sawdust Anti-Inflammatory Effect in Sows. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2017, 20, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, R.; Verma, P.K.; Peshin, R.; Kour, H. Potential of Juniperus Communis L. as a Nutraceutical in Human and Veterinary Medicine. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.; Seca, A. The Current Status of the Pharmaceutical Potential of Juniperus L. Metabolites. Medicines 2018, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, S.; Abrol, N.; Prashar, Y.; Kumari, R. Modulatory Effect of Standardised Amentoflavone Isolated from Juniperus communis L. Agianst Freund’s Adjuvant Induced Arthritis in Rats (Histopathological and X Ray Anaysis). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 86, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-J.; Yang, Y.-J.; Li, Y.-S.; Zhang, W.K.; Tang, H.-B. α-Pinene, Linalool, and 1-Octanol Contribute to the Topical Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Activities of Frankincense by Inhibiting COX-2. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, B.; Manjula, N.; Vinaykumar, K.S.; Lakshmi, B.S.; Balakrishnan, A. Pure Compound from Boswellia Serrata Extract Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Property in Human PBMCs and Mouse Macrophages through Inhibition of TNFα, IL-1β, NO and MAP Kinases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.-S.; Park, K.-C.; Choi, S.B.; Jo, I.-J.; Choi, M.-O.; Hong, S.-H.; Song, K.; Song, H.-J.; Park, S.-J. Protective Effects of Alpha-Pinene in Mice with Cerulein-Induced Acute Pancreatitis. Life Sci. 2012, 91, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Mao, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, R.; Jin, X.; Ye, L. Anti-Tumor Effect of α-Pinene on Human Hepatoma Cell Lines through Inducing G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 127, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuhara, M.; Urakami, K.; Masuda, Y.; Zangiacomi, V.; Ishii, H.; Tai, S.; Maruyama, K.; Yamaguchi, K. Fragrant Environment with α-Pinene Decreases Tumor Growth in Mice. Biomed. Res. 2012, 33, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, A.L.; Figueiredo, C.R.; Arruda, D.C.; Pereira, F.V.; Borin Scutti, J.A.; Massaoka, M.H.; Travassos, L.R.; Sartorelli, P.; Lago, J.H.G. α-Pinene Isolated from Schinus Terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) Induces Apoptosis and Confers Antimetastatic Protection in a Melanoma Model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 411, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Parker, T.L. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Juniper (Juniperus communis) Berry Essential Oil in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Cogent Med. 2017, 4, 1306200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowniak, K.; Mroczek, T.; Zobel, A.M. Seasonal Changes in the Concentrations of Four Taxoids in Taxus baccata L. during the Autumn-Spring Period. Phytomedicine 1999, 6, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobosch, T.; Schwarze, B.; Felgenhauer, N.; Riesselmann, B.; Roscher, S.; Binscheck, T. Eight Cases of Fatal and Non-Fatal Poisoning with Taxus Baccata. Forensic Sci. Int. 2013, 227, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.C.; Johnson, K.R.; Willingham, M.C.; Fan, W. Apoptotic Cell Death Induced by Baccatin III, a Precursor of Paclitaxel, May Occur without G 2/M Arrest. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1999, 44, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoka, L.; Nazaruk, J.; Stocki, M.; Isidorov, V. Santin and Cirsimaritin from Betula pubescens and Betula pendula Buds Induce Apoptosis in Human Digestive System Cancer Cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 11085–11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtari, M.S.; Majd, A.; Nejadsattari, T.; Moin, M.; Kardar, G.A. Novel Report of the Phytochemical Composition from Fraxinus Excelsior Pollen Grains. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2018, 91, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, A.; Jones, W.; Riedl, K.; Cipollini, D.; Schwartz, S.; Chan, K.; Herms, D.A.; Bonello, P. Comparative Phloem Chemistry of Manchurian (Fraxinus mandshurica) and Two North American Ash Species (Fraxinus americana and Fraxinus pennsylvanica). J. Chem. Ecol. 2007, 33, 1430–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palo, R.T. Distribution of Birch (Betula spp.), Willow (Salix spp.), and Poplar (Populus spp.) Secondary Metabolites and Their Potential Role as Chemical Defense against Herbivores. J. Chem. Ecol. 1984, 10, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullauer, F.B.; Kessler, J.H.; Medema, J.P. Betulin Is a Potent Anti-Tumor Agent That Is Enhanced by Cholesterol. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, H.S.; Sak, K.; Gupta, D.S.; Kaur, G.; Aggarwal, D.; Chaturvedi Parashar, N.; Choudhary, R.; Yerer, M.B.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Properties of Birch Bark-Derived Betulin: Recent Developments. Plants 2021, 10, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakurtti, S.; Mäkelä, T.; Koskimies, S.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J. Pharmacological Properties of the Ubiquitous Natural Product Betulin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, S.; Laszczyk, M.; Scheffler, A. A Preliminary Pharmacokinetic Study of Betulin, the Main Pentacyclic Triterpene from Extract of Outer Bark of Birch (Betulae alba Cortex). Molecules 2008, 13, 3224–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C.A.; Şoica, C.; Ledeţi, I.; Aluaş, M.; Zupko, I.; Gǎluşcan, A.; Cinta-Pinzaru, S.; Munteanu, M. Study of the Betulin Enriched Birch Bark Extracts Effects on Human Carcinoma Cells and Ear Inflammation. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.; Mocan, A.; Coșarcă, S.; Gavan, A.; Nicolescu, A.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Vodnar, D.C.; Muntean, D.-L.; Crișan, O. Biological and Chemical Insights of Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Bark: A Source of Bioactive Compounds with Functional Properties. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formato, M.; Piccolella, S.; Zidorn, C.; Vastolo, A.; Calabrò, S.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Pacifico, S. UHPLC-ESI-QqTOF Analysis and In Vitro Rumen Fermentation for Exploiting Fagus sylvatica Leaf in Ruminant Diet. Molecules 2022, 27, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzubak, P.; Hajduch, M.; Vydra, D.; Hustova, A.; Kvasnica, M.; Biedermann, D.; Markova, L.; Urban, M.; Sarek, J. Pharmacological Activities of Natural Triterpenoids and Their Therapeutic Implications. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D. Biosynthesis and Biological Functions of Terpenoids in Plants. In Biotechnology of Isoprenoids; Schrader, J., Bohlmann, J., Eds.; Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 148, pp. 63–106. ISBN 978-3-319-20106-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cör, D.; Knez, Ž.; Knez Hrnčič, M. Antitumour, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Antiacetylcholinesterase Effect of Ganoderma Lucidum Terpenoids and Polysaccharides: A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchino, S.A.; Butassi, E.; Liberto, M.D.; Raimondi, M.; Postigo, A.; Sortino, M. Plant Phenolics and Terpenoids as Adjuvants of Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs. Phytomedicine 2017, 37, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y.-M.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, H.-B.; Liang, D.-E.; Ma, L.-F.; Shan, W.-G.; Zhan, Z.-J. Terpenoids with Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity from the Submerged Culture of Inonotus Obliquus. Phytochemistry 2014, 108, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazaki, K.; Arimura, G.; Ohnishi, T. ‘Hidden’ Terpenoids in Plants: Their Biosynthesis, Localization and Ecological Roles. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telichowska, A.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Szulc, P. Phytopharmacological Possibilities of Bird Cherry Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. Species and Their Bioactive Phytochemicals. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, M.; Oguchi, K.; Yamaura, T.; Suzuki, M.; Cyong, J.-C. Protective Effect of Hawthorn Fruit on Murine Experimental Colitis. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2005, 33, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.d.d.; da Fonsec, A.P.; Lima, V.S.; Moya, A.M.T.M.; Reguengo, L.M.; Junior, S.B.; Leal, R.F.; Cao-Ngoc, P.; Christophe, P.C.; Leclercq, R.L.; et al. Chemoprevention with a Tea from Hawthorn (Crataegus oxyacantha) Leaves and Flowers Attenuates Colitis in Rats by Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirezalu, A.; Salehi, P.; Ahmadi, N.; Sonboli, A.; Aceto, S.; Hatami Maleki, H.; Ayyari, M. Flavonoids Profile and Antioxidant Activity in Flowers and Leaves of Hawthorn Species (Crataegus spp.) from Different Regions of Iran. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 452–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaei, M.H.; Ghasemi-Niri, S.F.; Abdolghafari, A.H.; Baeeri, M.; Khanavi, M.; Navaei-Nigjeh, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Rahimi, R. Biochemical and Histopathological Evidence on the Beneficial Effects of Tragopogon graminifolius in TNBS-Induced Colitis. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorski, H.; Sałaga, M.; Zielińska, M.; Piechota-Polańczyk, A.; Owczarek, K.; Kordek, R.; Lewandowska, U.; Chen, C.; Fichna, J. Experimental Colitis in Mice Is Attenuated by Topical Administration of Chlorogenic Acid. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2015, 388, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ruan, Z.; Mi, S.; Jiang, M.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Deng, Z.; Yin, Y. Chlorogenic Acid Ameliorates Intestinal Mitochondrial Injury by Increasing Antioxidant Effects and Activity of Respiratory Complexes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Liu, L.; Xing, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Cao, Y. Roles and Mechanisms of Hawthorn and Its Extracts on Atherosclerosis: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, M.; Hacıseferoğulları, H.; Marakoğlu, T.; Arslan, D. Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) Fruit: Some Physical and Chemical Properties. J. Food Eng. 2005, 69, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Peng, W.; Qin, R.; Zhou, H. Crataegus pinnatifida: Chemical Constituents, Pharmacology, and Potential Applications. Molecules 2014, 19, 1685–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.; Du, L.; Wang, N.; Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Yan, F.; Zhang, H. Effects of Haw Pectic Oligosaccharide on Lipid Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in Experimental Hyperlipidemia Mice Induced by High-Fat Diet. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, T.; Zhu, R.; Wang, N.; Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, M. Antibacterial Action of Haw Pectic Oligosaccharides. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Y. Antioxidant Activity of Penta-Oligogalacturonide, Isolated from Haw Pectin, Suppresses Triglyceride Synthesis in Mice Fed with a High-Fat Diet. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Hu, F.; Ning, C.; Chen, G. Pectin Oligosaccharides from Hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge. Var. Major): Molecular Characterization and Potential Antiglycation Activities. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, S.Y.; Yildirim, E. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Red Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) Using Citric Acid and Lemon Juice. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 6674–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud, A.; Vilcins, D.; McEwen, B. The Effect of Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review. Adv. Integr. Med. 2020, 7, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Mehri, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. The Effects of Crataegus pinnatifida (Chinese Hawthorn) on Metabolic Syndrome: A Review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieckiewicz, E.; Angenot, L.; Gras, T.; Kiss, R.; Frédérich, M. Potential Anticancer Activity of Young Carpinus betulus Leaves. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felegyi-Tóth, C.A.; Garádi, Z.; Darcsi, A.; Csernák, O.; Boldizsár, I.; Béni, S.; Alberti, Á. Isolation and Quantification of Diarylheptanoids from European Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS Characterization of Its Antioxidative Phenolics. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 210, 114554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahng, Y.; Park, J.G. Recent Studies on Cyclic 1,7-Diarylheptanoids: Their Isolation, Structures, Biological Activities, and Chemical Synthesis. Molecules 2018, 23, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Manjarres, J.F.; Gerard, P.R.; Dufour, J.; Raquin, C.; Frascaria-Lacoste, N. Differential Patterns of Morphological and Molecular Hybridization between Fraxinus excelsior L. and Fraxinus angustifolia Vahl (Oleaceae) in Eastern and Western France: Fraxinus hybridization in France. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 3245–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayouni, K.; Berboucha-Rahmani, M.; Kim, H.K.; Atmani, D.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Metabolomic Tool to Identify Antioxidant Compounds of Fraxinus Angustifolia Leaf and Stem Bark Extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 88, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’sou, S.; Alifriqui, M.; Romane, A. Phytochemical Study and Biological Effects of the Essential Oil of Fraxinus Dimorpha Coss & Durieu. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2797–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, I.; Iossifova, T. Chemical Components of Fraxinus Species. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wen, K.-S.; Ruan, X.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Wei, F.; Wang, Q. Response of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Environmental Factors. Molecules 2018, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Seeram, N.P. Maple Syrup Phytochemicals Include Lignans, Coumarins, a Stilbene, and Other Previously Unreported Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11673–11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, T.D.; van den Berg, A.K. Maple Syrup—Production, Composition, Chemistry, and Sensory Characteristics. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 56, pp. 101–143. ISBN 978-0-12-374439-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nahar, P.P.; Driscoll, M.V.; Li, L.; Slitt, A.L.; Seeram, N.P. Phenolic Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Properties of a Maple Syrup Extract in RAW 264.7 Murine Macrophages. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 6, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Zaid, M.; Nozzolillo, C.; Tonon, A.; Coppens, M.; Lombardo, D. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Characterization and Identification of Antioxidant Polyphenols in Maple Syrup. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D. The Chemical Composition of Maple Syrup. J. Chem. Educ. 2007, 84, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Seeram, N.P. Quebecol, a Novel Phenolic Compound Isolated from Canadian Maple Syrup. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Seeram, N.P. Further Investigation into Maple Syrup Yields 3 New Lignans, a New Phenylpropanoid, and 26 Other Phytochemicals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7708–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, J.; Girard-Lalancette, K.; Grenon, C.; Dussault, C.; Pichette, A. Antioxidant Activity, Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Overproduction, and In Vitro Antiproliferative Effect of Maple Sap and Syrup from Acer Saccharum. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, G.; Küpeli, E.; Memisoğlu, M.; Yesilada, E. Flavonoids with Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activities from the Leaves of Tilia argentea (Silver Linden). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; He, T.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Bai, S.; Wang, L.; Shen, M.; She, G. The Genus Alnus, A Comprehensive Outline of Its Chemical Constituents and Biological Activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Blanco, S.; Fernández, J.; Gutiérrez-del-Río, I.; Villar, C.J.; Lombó, F. New Insights toward Colorectal Cancer Chemotherapy Using Natural Bioactive Compounds. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaković, V.; Novaković, M.; Popović, Z.; Janković, M.; Matić, R.; Tešević, V.; Bojović, S. Significance of Diarylheptanoids for Chemotaxonomical Distinguishing between Alnus Glutinosa and Alnus Incana. Holzforschung 2017, 72, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresti, A.L. Curcumin for Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Review of in Vitro, Animal and Human Studies. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaterra, G.; Schwarzbach, H.; Kelber, O.; Weiser, D.; Kinscherf, R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Phytodolor® (STW 1) and Components (Poplar, Ash and Goldenrod) on Human Monocytes/Macrophages. Phytomedicine 2019, 58, 152868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, B.; Avram, S.; Pavel, I.Z.; Lombrea, A.; Buda, V.; Dehelean, C.A.; Soica, C.; Yerer, M.B.; Bojin, F.; Folescu, R.; et al. Recent Advances Regarding the Phytochemical and Therapeutic Uses of Populus nigra L. Buds. Plants 2020, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore, A.; Vulturescu, V.; Neagu, G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Populus nigra L. Buds. Chem. Proc. 2022, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, W.R.; Koski, R.D.; Negron, J.F. Dutch Elm Disease Pathogen Transmission by the Banded Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus Schevyrewi. For. Pathol. 2013, 43, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, E.B.; Guries, R.P. Breeding Elms for Resistance to Dutch Elm Disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1993, 31, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.A.; Solla, A.; Witzell, J.; Gil, L.; García-Vallejo, M.C. Antifungal Effect and Reduction of Ulmus Minor Symptoms to Ophiostoma Novo-Ulmi by Carvacrol and Salicylic Acid. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 127, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.A.; Domínguez, J.; Solla, A.; Brasier, C.M.; Webber, J.F.; Santini, A.; Martínez-Arias, C.; Bernier, L.; Gil, L. Complexities Underlying the Breeding and Deployment of Dutch Elm Disease Resistant Elms. N. For. 2021, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asolkar, R.N.; Cordova-Kreylos, A.; Himmel, P.; Marrone, P. Discovery and Development of Natural Products for Pest Management. In Pest Management with Natural Products; ACS Symposium Series; Beck, J., Coats, J., Duke, S., Koivunen, M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1141, pp. 17–30. ISBN 978-0-8412-2900-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rimando, A.M.; Duke, S.O. (Eds.) Natural Products for Pest Management; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8412-3933-3. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez, F. Biological Activities of Fungal Metabolites. In Handbook of Industrial Mycology; An, Z., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 49–92. ISBN 978-0-429-22456-0. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, G.A.; Miller, R.V.; Martinez-Miller, C.; Condron, M.M.; Teplow, D.B.; Hess, W.M. Cryptocandin, a Potent Antimycotic from the Endophytic Fungus Cryptosporiopsis Cf. Quercina. Microbiology 1999, 145, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cai, X.-L.; Yang, H.; Xia, X.-K.; Guo, Z.-Y.; Yuan, J.; Li, M.-F.; She, Z.-G.; Lin, Y.-C. The Bioactive Metabolites of the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Talaromyces sp. ZH-154 Isolated from Kandelia candel (L.) Druce. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debbab, A.; Aly, A.H.; Proksch, P. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Endophytes and Associated Marine Derived Fungi. Fungal Divers. 2011, 49, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Nicoletti, R.; Lacatena, F.; Marra, R.; Sacco, A.; Lombardi, N.; d’Errico, G.; Digilio, M.C.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S.L. Secondary Metabolites from the Endophytic Fungus Talaromyces Pinophilus. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 1778–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-Q.; Li, X.-J.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, A.-L.; Gao, J.-M.; Zhang, X.-C. Antifungal Metabolites from Chaetomium Globosum, an Endophytic Fungus in Ginkgo Biloba. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, J.; Gao, Y.-Q.; Tang, J.; Zhang, A.-L.; Gao, J.-M. Chaetoglobosins from Chaetomium globosum, an Endophytic Fungus in Ginkgo Biloba, and Their Phytotoxic and Cytotoxic Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3734–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, F.; Cabello, A.; Platas, G.; Díez, M.T.; del Val, A.G.; Basilio, A.; Martán, I.; Vicente, F.; Bills, G.F.; Giacobbe, R.A.; et al. The Discovery of Enfumafungin, a Novel Antifungal Compound Produced by an Endophytic hormonema Species Biological Activity and Taxonomy of the Producing Organisms. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 23, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Bai, L. Studies on a Chlorogenic Acid-Producing Endophytic Fungi Isolated from Eucommia Ulmoides Oliver. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 37, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W. Bioactive Metabolites from Alternaria Brassicicola ML-P08, an Endophytic Fungus Residing in Malus halliana. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eranthodi, A.; Schneiderman, D.; Harris, L.J.; Witte, T.E.; Sproule, A.; Hermans, A.; Overy, D.P.; Chatterton, S.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; et al. Enniatin Production Influences Fusarium Avenaceum Virulence on Potato Tubers, but Not on Durum Wheat or Peas. Pathogens 2020, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically Active Secondary Metabolites from the Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräse, S.; Encinas, A.; Keck, J.; Nising, C. Chemistry and Biology of Mycotoxins and Related Fungal Metabolites. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3903–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusztahelyi, T.; Holb, I.J.; Pócsi, I. Secondary Metabolites in Fungus-Plant Interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demain, A.L.; Fang, A. The Natural Functions of Secondary Metabolites. In History of Modern Biotechnology I; Fiechter, A., Ed.; Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 69, pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-3-540-67793-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.Y.; Tatsumura, Y. Alexander Fleming (1881–1955): Discoverer of Penicillin. Singap. Med. J. 2015, 56, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Natural Products: A Continuing Source of Novel Drug Leads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3670–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydametova, E.; Zainol, N. Morphological, Physiological, Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of Statin-Producing Penicillium Microfungi Isolated from Little-Explored Tropical Ecosystems. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizukojć, M.; Ledakowicz, S. Biosynteza Lowastyny Przez Aspergillus Terreus. Biotechnologia 2005, 2, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, K.J.; Hans, M.; Meijrink, B.; van Scheppingen, W.B.; Vollebregt, A.; Tee, K.L.; van der Laan, J.-M.; Leys, D.; Munro, A.W.; van den Berg, M.A. Single-Step Fermentative Production of the Cholesterol-Lowering Drug Pravastatin via Reprogramming of Penicillium Chrysogenum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2847–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.R.; Mascitelli, L. Do Statins Cause Diabetes? Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013, 13, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Koyasu, S. Mechanisms of Action of Cyclosporine. Immunopharmacology 2000, 47, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, S.; Nie, S.; Marcone, M. Properties of Cordyceps Sinensis: A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Li, J.; Gu, B.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; Xie, X.; Cao, L. Extracts of Cordyceps Sinensis Inhibit Breast Cancer Cell Metastasis via Down-Regulation of Metastasis-Related Cytokines Expression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 214, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.-H.; Zhong, J.-J. Secondary Metabolites from Cordyceps Species and Their Antitumor Activity Studies. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2007, 1, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Tree Species | Isolated From | Structural Classification | Examples of Secondary Metabolites | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus sylvestris | Needles, wood | Monoterpenes | α-Thujene, α-Pinene, Camphene, β-Pinene, Limonene, Terpinolene | [57] |

| Sesquiterpenoids | β-Caryophyllene, β-Copaene, α-Cadinol, Aromadendrene | |||

| Bark, cones | Flavonoids | Catechin, Epicatechin, Epigallocatechin gallate, Verbascoside Caffeic acid | [118,119] | |

| Buds | Non-protein amino acids | Cystathionine, β-Alanine, β-Aminobutyric, γ-Aminobutyric, Ornithine | [120] | |

| Needles | Proanthocyanidins | Prodelphinidins and Propelargonidins catechin derivatives | [121] | |

| Phenolic acids | Caffeic acid, Salicylic acid, Ferulic acid, Vanillic acid, Gallic acid, Sinapic | |||

| Pinus mugo | Needles | Monoterpenes | α-Pinen, β-Pinen, Mircen, α-felandren, Terpinolene, Linalol | [122] |

| Diterpenes | α-Cadinol, abietatriene, Dehydroabietol, Pimaradiene | |||

| Pinus pumila | Cones | Flavonoids | Chrysin, Luteolin, Quercetin, Taxifolin, Dihydromyricetin | [123] |

| Pinus banksiana | Wood with knots | Flavonoids | Pinobanksin, Pinocembrin, Taxifolin, Naringenin, Dihydrokaempferol | [124] |

| Pinus nigra | Foliage | Monoterpenes | β-phellandrene, α-Pinene, β-Pinene, Camphene, Myrcene, Limonene, Terpinene, Linalool | [125] |

| Pinus yunnanensis | Foliage | Flavonols | Taxifolin derivative | [126] |

| Lignans | Erythro-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methooxy- phenyl)-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3-hydroxypropyl) phenoxy]- 1,3-propanediol, threo-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methooxy- phenyl)-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)henoxy]-1,3- propanediol | |||

| Diterpenes | Iso-Cupressic acid, Agathic acid, Pinifolic acid, Agatholic acid, Agathic acid, 15-methyl ester | |||

| Pinus roxburghii | Bark | Flavonoids | Taxifolin, Taxifolin derivative, Quercetin, Catechin | [127] |

| Lignans | Pinoresinol, Secoisolariresinol | |||

| Phenolic acids | Protocatechuic acid | |||

| Stilbenes | Monomethyl Pinosylvin | |||

| Pinus wallichiana | Bark | Flavonoids | Quercetin, Taxifolin derivative, Catechin, Catechin, Gallocatechin derivative | |

| Stilbenes | Monomethyl Pinosylvin, Dihydro-monomethyl Pinosylvin | |||

| Lignans | Secoisolariresinol | |||

| Phenolic acids | Protocatechuic acid | |||

| Pinus gerardiana | Bark | Flavonoids | Taxifolin, Taxifolin derivative, Quercetin, Catechin | |

| Phenolic acids | Protocatechuic acid | |||

| Stilbenes | Dihydro-monomethyl Pinosylvin | |||

| Pinus kesia | Bark | Phenolic acids | Caffeic acid, Gallic acid, Chlorogenic acid | |

| Pinus merkusii | Bark | Stilbenes | Pinosylvin monomethyl ether, Pinosylvin dimethyl ether | |

| Flavonoids | Pinocembrim | |||

| Picea abies | Needles | Phenolic acids | Shikimic acid, Galusic acid, p-Coumaric acid, Protocatechuic acid, Ferulic, Vanillic, Syringic, Sinapic, Salicylic, Quinic acids, Protocatechuic, Gallic acids | [121] |

| Flavonoids | Catechin, Kaempferol 3-glucoside, Naringenin, Quercetin, Quercetin 3-glucoside, Quercitrin Catechin, | [128] | ||

| Stilbenes | Cis-astringin, Trans-astringin, Trans-piceatannol, Cis-piceid, Trans-piceid, Trans-resveratrol | [121] | ||

| Branches | Monoterpenes | α-Pinen, β-Pinen, Limonen, Myrcene, Limonene, γ-Terpinene, Geraniol | [129] | |

| Emission, needles, xylem, bark, wood, roots | Linalool, Camphor, Borneol, Piperitone, β-pinene, Terpinolene, α-pinene, Camphene, p-Cymene | [130] | ||

| Sesquiterpenes | β-Caryophyllene, Longifolene | |||

| Picea jezoensis | Needles, bark, wood | Stilbenes | Trans-astringin, Cis-astringin, Trans-piceid, Trans-piceatannol, Trans-resveratol, Cis-isorhapontigenin | [131] |

| Abies alba | Branches | Monoterpenes | α-Pinen, β-Pinen, Limonen, Myrcene, Limonene, γ-Terpinene, Geraniol | [129] |

| Needles | Sesquiterpenes | β-Caryophyllene, α-Humulene, Santene | [132] | |

| Taxus baccata | Needles, branches | Alkaloids | 10-Deacetylbaccatin III, Baccatin III, Cephalomannine, Taxinine M, Taxol A | [133] |

| Tree Species | Isolated from | Structural Classification | Examples of Secondary Metabolites | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betula pubescens | Buds | Flavonoids | Kaempferol, Apigenin, Quercetin | [156] |

| Betula pendula | Kaempferol, Apigenin, Quercetin | |||

| Fraxinus excelsior | Pollen grains | Monoterpenes | α-Pinen, Sambiene, α-Terpinene, β-Pinene, Linalool, α-Terpineol | [157] |

| Sesquiterpene | Calarene, α-copaenem β-cubebene, α -muurolene, T-cadinol | |||

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica | Phloem | Flavones | Apigenin | [158] |

| Glycosides | Ligustroside, Oleuropein, Verbascoside | |||

| Lignans | Syringaresinol | |||

| Fraxinus mandshurica | Glycosides | Ligustroside, Oleuropein, Verbascoside, Calceolarioside A, Esculin, Calceolarioside B, Fraxin | ||

| Fraxinus americana | Flavones | Apigenin | ||

| Glycosides | Ligustroside, Oleuropein, Verbascoside | |||

| Lignans | Syringaresinol | |||

| Populus tremula | Bark | Glycosides | Salicis, Salicortin, Salireposide, Gradidentanin | [159] |

| Buds, foliage | Flavonoids | Kaempferol, Apigenin-4-Me, Chrysin, Galagnin, Pinocembrin | ||

| Foliage | Glycosides | Salicortin | ||

| Populus tremuloides | Bark | Glycosides | Salicortin, Salireposide, Gradidentanin | |

| Buds, foliage | Flavonoids | Quercetin, Chrysin, Pinocembrin | ||

| Foliage | Glycosides | Salicortin | ||

| Populus alba | Bark | Glycosides | Salicortin, Salireposide, Gradidentanin | |

| Foliage | Salicortin, Gradidentanin | |||

| Populus nigra | Bark | Glycosides | Salicortin | |

| Foliage | Salicortin | |||

| Populus trichocarpa | Bark | Glycosides | Salicortin, Salireposide, Vimalin | |

| Foliage | Salicortin, Salireposide, Vimalin | |||

| Populus candicans | Bark | Glycosides | Salicortin, Salireposide, Vimalin | |

| Buds, foliage | Flavonoids | Quercetin, Luteolin, Myricetin | ||

| Foliage | Glycosides | Salicortin, Salireposide, Vimalin | ||

| Salix alba | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Grandidentanin, Triandrin | |

| Salix aurita | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Triandrin, Vimalin | |

| Salix caprea | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Triandrin, Fragilin | |

| Salix fragilis | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Grandidentanin, Triandrin, Fragilin | |

| Foliage | Salicin, Salicortin | |||

| Salix myrsinifolia | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Picein, Triandrin, | |

| Foliage | Salicin, Salicortin | |||

| Salix pentandra | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Grandidentanin, Triandrin, | |

| Foliage | Salicin, Salicortin | |||

| Salix purpurea | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Salireposide, Grandidentanin, | |

| Foliage | Salicin, Salicortin | |||

| Salix repens | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salicortin, Salireposide, Grandidentanin, | |

| Foliage | Salicin, Salicortin | |||

| Salix triandra | Bark | Glycosides | Salicin, Salireposide, Tremulacin, Grandidentanin, Triandrin | |

| Foliage | Tremulacin | |||

| Salix viminalis | Foliage | Glycosides | Salicin, Salireposide, Triandrin, Vimalin |

| Species of Fungi | Host Plant | Isolated from | Examples of Secondary Metabolites | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporiopsis cf. quercine | Tripterygium wilfordii | Stems | Cryptocin | [222] |

| Pestalotiopsis fici | unidentified | Branches | Skyrin, Secalonic acid A, Emodin, Norlichexanthone | [223,224] |

| Talaromyces pinophilus | Arbutus unedo | Branches | Herquline B, 3-O-methylfunicone | [225] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Ginkgo biloba | Leaves | Gliotoxin, epipolythiodioxopiperazine | [226,227] |

| Hormonema sp. | Juniperus communis | Leaves | Enfumafungin | [228] |

| Sordariomycete sp. | Euconia ulmoides | Leaves, roots | Chlorogenic acid | [229] |

| Alternaria brassicicola | Mallus halliana | Leaves | Alternariol 9-methyl ether, altechromone A, herbarin A, cerevisterol, 3b,5a-dihydroxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-7,22-dien-6-one | [230] |

| Fusarium avenaceum | Abies balsamea | Foliage | Enniatin A | [231] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nawrot-Chorabik, K.; Sułkowska, M.; Gumulak, N. Secondary Metabolites Produced by Trees and Fungi: Achievements So Far and Challenges Remaining. Forests 2022, 13, 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081338

Nawrot-Chorabik K, Sułkowska M, Gumulak N. Secondary Metabolites Produced by Trees and Fungi: Achievements So Far and Challenges Remaining. Forests. 2022; 13(8):1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081338

Chicago/Turabian StyleNawrot-Chorabik, Katarzyna, Małgorzata Sułkowska, and Natalia Gumulak. 2022. "Secondary Metabolites Produced by Trees and Fungi: Achievements So Far and Challenges Remaining" Forests 13, no. 8: 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081338

APA StyleNawrot-Chorabik, K., Sułkowska, M., & Gumulak, N. (2022). Secondary Metabolites Produced by Trees and Fungi: Achievements So Far and Challenges Remaining. Forests, 13(8), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081338