Forest Biomass Policies and Regulations in the United States of America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Policy Background

- Financial (loan, tax, fee, charge, fine, insurance, and price)

- Promotional (cash grants, loan guarantee, public investment, government provision, public promotion, and kind transfer)

- Motivational (information, demonstration, and government-sponsored enterprise)

- Regulatory (quality control, guideline, prohibition, quota, and ban)

- Administrative (certification, screening, license, permit, lease, and contract)

3. Federal Policies and Incentives

Timber Sale Regulations

4. State Policies Related to Woody Biomass

Policy Effectiveness

5. Discussion

Policy Language

6. Increasing the Use of Woody Biomass in the U.S.

- Multiple definitions are contained within different programs supporting the use of forest biomass for bioenergy and other bioproducts. The restriction for using biomass from public lands discourages private industry investments and it decreases the opportunity to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by producing biofuels from sustainably harvested low-grade wood to mitigate the impacts of climate change, to reap the associated benefits for the environment, and to improve rural community economies. It also implies that the cost of hazardous fuels materials cannot be decreased when managing public lands because the material cannot be used for bioenergy or biofuels production. This limits an agency’s capacity to implement active forest management and successful implementation of the USDA-FS Wildland Fire Strategy for Protecting Communities and Improving Resilience in America’s Forests. This is important because it could leave out the use of about 210 million oven dry tons of small-diameter and harvest residue material that could be removed through hazard-fuel treatments in the western U.S. [33].Current U.S. policies direct the federal government, aircraft manufacturers, airlines, fuel producers, airports, and non-governmental organizations to advance the use of cleaner and more sustainable fuels in aviation. These steps make progress toward U.S. climate goals for 2030 and are essential to unlocking the potential for a fully zero-carbon aviation sector by 2050. The aim is to produce three billion gallons of sustainable fuel, reduce aviation emissions by 20% by 2030, and grow good-paying union jobs [34]. Forest biomass could be an important source of raw material for this purpose. However, for the U.S. to be able to accomplish this mandate, all agencies and departments involved need to establish clear definitions of the 42 U.S. Code § 7545(Regulation of fuels (I) Renewable biomass from (v) Biomass obtained from the immediate vicinity of buildings and other areas regularly occupied by people, or of public infrastructure, at risk from wildfire [35]. This work will involve the USDA-FS and EPA to get clarification and guidance on what constitutes qualified renewable biomass and the distance it can be obtained from federal lands surrounding buildings, other areas regularly occupied by people, or public infrastructure in the area at risk for wildfire. Currently, a distance of 200 feet (61 m) has been mentioned but given the current environmental conditions of extreme fire behavior that may occur during intense drought, hot temperatures, and very high winds, this distance may not be sufficient to effectively provide a wildfire fuel break. Additional considerations are defining the forestry terms and concepts included in the RFS code such as slash, pre-commercial thinnings, and wood from plantations. Using standard definitions currently provided in academic literature would assist in bringing consistency to policies and regulations. Soon RIN registrations for woody biomass-derived electricity that displaces liquid fuels in electric and hydrogen vehicles will be needed.

- Forest biomass definitions can be used to limit bioenergy or bioproducts to avoid industry competition for raw materials and promote unsustainable forest management [18,30]. Alignment and consistency of forest biomass and related definitions are an important topic to analyze and propose solutions, so all sectors have the same understanding.

- Lack of alignment between some national and state policies for the use of forest biomass creates increased cost and uncertainty (i.e., Clean Air regulations). Abrams et al. [22] point out that the biomass policy system in the U.S. may not be well designed to support innovation, particularly due to conflicts between forest biomass use promotion policies and other forest, environmental, or energy policies.

- Additional factors that affect how state and federal energy policies impact the forest bioenergy sector are pending or near final court rulings. These bioenergy policies can deter or stall investments and expansion of rural economies. Changes in the legal definition of forest bioenergy and its eligibility in policy (e.g., Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS)) can influence harvesting practices, site sustainability, and feedstock availability (e.g., removal of forest biomass from federal lands) [21].

- RPS are a regulatory mandate to increase production of energy from renewable sources such as wind, solar, biomass, and other alternatives to fossil and nuclear electric generation. It is also known as a renewable electricity standard [12,35]. Currently, 30 States and the District of Columbia have RPSs, 5 states have a Clean Energy Standard, 8 states have renewable portfolio goals, and 5 states have clean energy goals [36]. This is important, because RPS can set limits in the U.S. for forest biomass used for electricity production. The implication of this is that when forest biomass supplies are limited, using wood as an energy feedstock can increase competition for the material between the bioenergy sector and the pulp and paper industry. In addition, there are concerns that burning biomass could reduce air quality by releasing particulate matter [21].

- There are several policies that are not directly linked to, or specifically designed for, dealing with forest biomass. However, they have a high degree of influence on the different programs. This situation creates an imbalance between support for using forest biomass and limits of harvest operations because of a high standard within the regulations. Examples are national environmental policies such as the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and policies regulating USDA-FS National Forest System management. Furthermore, at the state level there are additional forest management policies, such as forest management and climate change action plans. It is important to analyze and create a consistent design or mix of regulations that could have the same standards but aligned with the new reality.

- Other aspects to be considered are high transportation costs. Forest biomass transportation cost is a major concern, and this is where designing policies that consider incentives for transportation costs could help reduce the cost of the supply chain and promote forest biomass use in the western US, where federal lands are located at long hauling distances from the processing facilities.

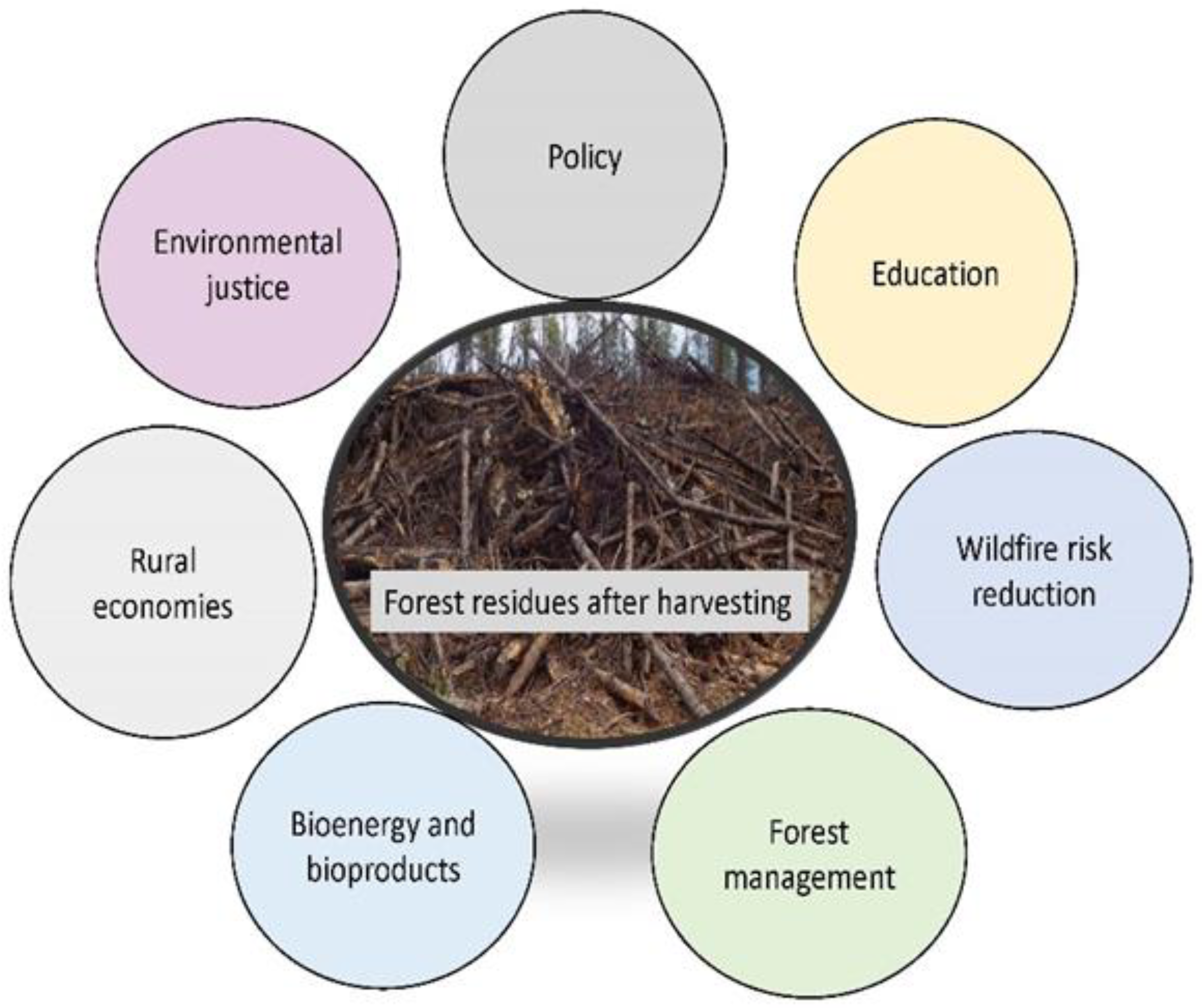

- Increasing education efforts can create, raise, sustain, and develop public awareness to increase knowledge and build positive attitudes for early and sustained adoption of bioenergy and bioproducts. Current efforts can be intensified to change public behaviors in both rural and urban households, industries, and communities.

7. Future Considerations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Appendix A

| Implementing Agency | Legislation | Legal and Regulatory Instruments | Main Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Instrument | Existing Legislation | Production | Mandate | Funding Mechanism | ||

| Biomass Research and Development Board US Department of Agriculture | Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000, as amended | Legislative-R&D and Demonstration | Yes | Government | Coordinates federal policies and procedures for promoting R&D and Demonstration activities leading to production of biofuel and biobased products | Same as Biomass R&D Advisory Committee |

| Biomass Research and Development Technical Advisory Committee (Department of Energy/Department of Agriculture) | The Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000, as amended | Legislation—R&D and Demonstration | Yes | Education Institutions, private industry and environmental interest groups | Promotes development of new and emerging technologies for the use of biomass, including processes of production of bio-based fuels and biobased products. Promotes R&D and Demonstration activities to advance the availability of new technology for the conversion and the use of Biofuels and biobased products | USD 5 million from Commodity Credit Corporation for 2002 and USD 14 million/year in the period 2003/2007 + USD 200 million/year in the period 2006/2015 |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002 | Legislation—Omnibus | Yes | sec IX Energy Sec 1 commodities programs; Sec 2 conservation; Sec 3 Trade; Sec 4 Nutrition Program; Sec 5 credit; Sec 6 Rural development; Sec 7 Research and related matters; Sec 8 Forestry; Sec 10 Miscellaneous | Conservation Security Program (CSP) provides payments and incentives for further environmental management and conservation by farmers who are already implementing such practices. This is a comparatively new program with spending amounts to USD 260 million annually | |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9002, Federal Procurement of Bio-based Products; | Legislation—Guidelines | Yes | Government | Establishes a new program for purchase of bio-based products by federal agencies, modeled on the existing program for purchase of recycled materials. A voluntary bio-based labeling program is included. Designed to increase the use of voluntary certification frameworks in the production of bio-based products | Mandates funding of USD 1 million annually through the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) for fiscal years (FY) 2002-07 for testing bio-based products |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9003, Bio-refinery Grants; | Legislation—Incentives | Yes | Industry | Establishes a competitive grant program to support development of bio-refineries to convert biomass into multiple products such as fuels, chemicals, and electricity. Provides grants for up to 30% of the costs for development of new and emerging technologies for the use of biomass, including lignocellulosic biomass | Authorization only, no funding |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9004, Biodiesel Fuel Education Program; | Legislation—Incentives and Education | Yes | Government/Private Entities | Establishes a competitive grant program to educate government and private entities with vehicle fleets, as well as the public, about the benefits of Biodiesel fuel use. Promotes the use of Biodiesel fuel in the by raising public awareness on the benefits of utilizing this bio-fuel source for transport | USD 1 million/year from Commodity Credit Corporation in the period 2002–2007. |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9005, Energy Audit and Renewable Energy Development Program; | Legislation—Information | Yes | Farmers, Ranchers, and Rural Small Business | Authorization only, no funding Authorizes a competitive grant program for the administration of energy audits and renewable energy development assessments to include bioenergy and energy crops. Promotes the use of biomass (and renewable in general) by showing to farmers, ranchers and rural small businesses the economic advantage of their use in production schemes | |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9006, Renewable Energy Systems and Energy Efficiency Improvements; Farm Act 2002 | Legislation—Incentives | Yes | Farmers, Ranchers, and Rural Small Business | Establishes a loan/loan guarantee/grant program to assist eligible farmers, ranchers, and rural small businesses in purchasing renewable energy systems and making energy efficiency improvements. Supports end-use implementation and access to bioenergy for farmers, ranchers and rural small business | USD 23 million/year from Commodity Credit Corporation in the period 2002–2007 |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9008, Biomass Research and Development; | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Academic Institutions | Promotes research and development activities for development of new and emerging bioenergy technologies and processes for production of bio-based fuels, including biomass. Promotes new and emerging technologies for use in the production of biofuels and bioenergy. | USD 54 million from Commodity Credit Corporation for 2002 and USD 63 million/year in the period 2003–2007 |

| Department of Agriculture | Farm Act 2002. Section 9010, Bioenergy Program; | Legislation—Incentive and Targets | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy. | Lays out targeted incentives based on production levels. Production less than 65,000,000 gallons of bioenergy reimbursed at 1 feedstock unit for every 2.5 feedstock units of eligible commodity used for increased production; Producers of more than 65,000,000 gallons of bioenergy reimbursed at 1 feedstock unit for every 3.5 feedstock units of eligible commodity used for increased production. Encourages increased purchase of eligible commodities (energy feedstocks) for the purpose of expanding production of bioenergy and supporting new production capacity | USD 150 million/year from Commodity Credit Corporation in the period 2003–2007. |

| Department of Agriculture | Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003. Section 201 Improved Biomass Use Research Program | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Academic Institutions | Title II Biomass (a) Uses of Grants, Contracts, and Assistance. —Section 307(d) of the Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000 (7 U.S.C. 7624 note; Public Law 106–224) is amended. Research to integrate silviculture, harvesting, product development, processing information, and economic evaluation to provide the science, technology, and tools to forest managers and community developers for use in evaluating forest treatment and production alternatives, including—(A) to develop tools that would enable land managers, locally or in a several-State region, to estimate— (i) the cost to deliver varying quantities of wood to a particular location; and (ii) the amount that could be paid for stumpage if delivered wood was used for a specific mix of products; (B) to conduct research focused on developing appropriate thinning systems and equipment designs that are—‘(i) capable of being used on land without significant adverse effects on the land; (ii) capable of handling large and varied landscapes; (iii) adaptable to handling a wide variety of tree sizes; (iv) inexpensive; and(v) adaptable to various terrains; and (C) to develop, test, and employ in the training of forestry managers and community developers curricula materials and training programs on matters described in subparagraphs (A) and (B). | (b) Funding—Section 310(b) of the Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000 (7 U.S.C. 7624 note; Public Law 106–224) is amended by striking ‘‘USD 49,000,000′’ and inserting ‘‘USD 54,000,000′’. |

| Department of Agriculture | Sec. 202. Rural Revitalization through Forestry | Legislation S&PF | Yes | Government | Section 2371 of the Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990 (7 U.S.C. 6601) is amended by adding at the end the following: (d) Rural Revitalization Technologies—(1) in general.—The Secretary of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service, in consultation with the State and Private Forestry Technology Marketing Unit at the Forest Products Laboratory, and in collaboration with eligible institutions, may carry out a program—(A) to accelerate adoption of technologies using biomass and small-diameter materials; (B) to create community-based enterprises through marketing activities and demonstration projects; and (C) to establish small-scale business enterprises to make use of biomass and small-diameter materials. | (2) Authorization of Appropriations—There is authorized to be appropriated to carry out this subsection USD 5,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2004 through 2008. |

| Department of Agriculture | Sec. 203. Biomass Commercial Utilization Grant Program | Legislation S&PF | Yes | Government | (a) In General—In addition to any other authority of the Secretary of Agriculture to make grants to a person that owns or operates a facility that uses biomass as a raw material to produce electric energy, sensible heat, transportation fuel, or substitutes for petroleum-based products, the Secretary may make grants to a person that owns or operates a facility that uses biomass for wood-based products or other commercial purposes to offset the costs incurred to purchase biomass. | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Sec. 203. Federal Purchase Requirement | Legislation–Mandates | Yes | Government | (b) Definitions—In this section: (1) Biomass—The term ‘‘biomass’’ means any lignin waste material that is segregated from other waste materials and is determined to be nonhazardous by the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and any solid, nonhazardous, cellulosic material that is derived from— (A) any of the following forest-related resources: mill residues, precommercial thinnings, slash, and brush, or nonmerchantable material; (B) solid wood waste materials, including waste pallets, crates, dunnage, manufacturing and construction wood wastes (other than pressure-treated, chemically treated, or painted wood wastes), and landscape or right-of-way tree trimmings, but not including municipal solid waste (garbage), gas derived from the biodegradation of solid waste, or paper that is commonly recycled; | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 701, Use of Alternative Fuels by Dual-Fueled Vehicles. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Government | This mandate modifies 42 USC 13212 (EPA act 1992 Section 303 Requires U.S. Government vehicle fleets to use alternative fuels in dual-fuel vehicles unless the Secretary of Energy determines an agency qualifies for a waiver. Grounds for a waiver are: alternative fuel is not reasonably available to the fleet and the cost of alternative fuel is unreasonably more expensive that convention fuel. Promotes use of biofuels in transport fleets used by government—Leading by example | (b) Authorization of Appropriations—There is authorized to be appropriated to carry out this section USD 5,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2004 through 2008. |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 703, Incremental Cost Allocation. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Government | Amending Section 303 of the Energy Policy Act of 1992. Requires the U.S. General Services Administration (and other federal agencies that procure vehicles for fleets) to spread the incremental vehicle costs of all vehicles. Promotes the use of energy efficient vehicles in Government vehicle fleets. | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 704, Alternative Compliance for State and Flexibility. | Legislation—Strategy | Yes | Government | Amending the Title V of the Energy Policy Act of 1992 Establishes flexible compliance options under the Environmental Protection Act of 1992 to allow agencies to choose a petroleum reduction path for their vehicle fleets in lieu of acquiring Alternative Fuel Vehicles (AFVs). Program has a waiver requirement where agencies can provide evidence to DOE that their petroleum reduction program will achieve results equivalent to alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs) running on alternative fuels 100% of the time. Promotes use of biofuels and energy efficient transportation models at the government level | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 705, Report Concerning Compliance with Alternative Fueled Vehicle Purchasing Requirements; | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Department of Energy | Establishes annual agency reporting date of February 15th, for Executive Order 13149 Compliance Reporting to Congress on use of Alternative Fuel Vehicles in government fleets. Establishes national reporting structure for review and analysis by Legislative bodies on government use and implementation of alternative fuel vehicles | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 706, Joint Flexible Fuel/Hybrid Vehicle Commercialization Initiative; | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Industry/Private Sector/Non-Profit Sector | Establishes a research program to advance the commercialization of flexible fuel or plug-in hybrid vehicles. The Act requires vehicles to achieve at least 250 miles per petroleum gallon. Promotes development of alternative energy vehicles for transport with a goal of increasing energy efficiency | Government allocation of USD 3,000,000 for fiscal year 2005/USD 7,000,000 for fiscal year 2006/USD 10,000,000 for fiscal year 2007/USD 20,000,000 for fiscal year 2008 |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. sec 1501, Extension and Modification of Renewable Electricity Production Credit | Legislation—Targets and Mandates | Yes | Industry/Transport | This section establishes a program requiring gasoline sold in the United States to be mixed with increasing amounts of renewable fuel (usually ethanol) on an annual average basis. In 2006, 4 billion gallons of renewable fuels are to be mixed with gasoline, and this requirement increases annually to 7.5 billion gallons of renewable fuel by 2012. For 2013 and beyond, the required volume of renewable fuel will include a minimum of 250 million gallons of cellulosic ethanol. Establishes blending mandates and Incrementally increases in the use of ethanol for transportation by setting minimum targets | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 902, Bioenergy Program | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Industry/Academic Institutions | Provides a framework for Department of Energy biomass and bio-product programs to partner with industrial and academic institutions to advance the development of biofuels, bio-products, and bio-refineries. Sets goals for promoting use of biotechnology and other advanced processes to make biofuels from lignocellulosic feedstocks cost-competitive with gasoline and diesel, increasing production of bio-products that reduce the use of fossil fuels in manufacturing facilities, and demonstrating the commercial application of integrated bio-refineries that use a wide variety of lignocellulosic feedstocks to produce liquid transportation fuels, high-value chemicals, electricity, and useful heat. | USD 167,650,000 for fiscal year 2006; USD 180,000,000 for fiscal year 2007; and USD 192,000,000 for fiscal year 2008. |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 941, Amendments to the Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000. | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Academic Institutions | Promotes development of crops and crop systems that improve feedstock production and processing; convert recalcitrant cellulosic biomass into intermediates that can be used to produce bio-based fuels and products; develop technologies that yield a wide range of bio-based products that increase the feasibility of fuel production in a bio-refinery; analyze biomass technologies for their impact on sustainability and environmental quality, security, and rural economic development. Promotes development of crops and crops systems that improve feedstock production. Creates systems for conversion of recalcitrant cellulosic biomass into intermediates that can be used to produce Biobased fuels/develop of technologies to increase efficiency of bio refineries | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2005. Section 932, Bioenergy Program; | Legislation—R&D | Yes | Industry/Academic Institutions | Develop, in partnership with industry and institutions of higher education: advanced biochemical and thermochemical conversion technologies capable of making fuels from lignocellulosic feedstocks that are price-competitive with gasoline or diesel in either internal combustion engines or fuel cell-powered vehicles; advanced biotechnology processes capable of making biofuels and bioproducts with emphasis on development of biorefinery technologies using enzyme-based processing systems; advanced biotechnology processes capable of increasing energy production from lignocellulosic feedstocks, with emphasis on reducing the dependence of industry on fossil fuels in manufacturing facilities; and other advanced processes | |

| Department of Energy | Section 942, Production Incentives for Cellulosic Biofuels; Energy Act 2005 | Legislation—Incentives and Targets | Yes | Producers | Accelerate deployment and commercialization of biofuels; deliver the first 1,000,000,000 gallons in annual cellulosic biofuels production by 2015; Ensure biofuels produced after 2015 are cost competitive with gasoline and diesel; and ensure that small feedstock producers and rural small businesses are full participants in the development of the cellulosic biofuels industry. Authorizes the establishment of incentives to ensure that annual production of one billion gallons of cellulosic biofuels is achieved by 2015 | USD 213,000,000 for fiscal year 2007; USD 251,000,000 for fiscal year 2008; and USD 274,000,000 for fiscal year 2009 |

| Departments of Energy and Agriculture (Biomass Research and Development Technical Advisory Committee) | Energy Act 2005. Section 941, Amendments to the Biomass Research and Development Act of 2000; | Legislation—FACA | Yes | Industry, Academic, State, Environmental, Government, Trade Association, Analyst, Economist. Government | Established a Federal Advisory Committee to advise the Secretary of Energy, the Secretary of Agriculture, and the points of contact concerning: the technical focus and direction of requests for proposals issued under the Initiative; and procedures for reviewing and evaluating the proposals; to facilitate consultations and partnerships among Federal and State agencies, agricultural producers, industry, consumers, the research community, and other interested groups to carry out program activities relating to the Initiative; and to evaluate and perform strategic planning on program activities relating to the Initiative. Establishes an Interagency Board to coordinate programs within and among departments and agencies of the Federal Government for the purpose of promoting the use of biobased industrial products by maximizing the benefits deriving from Federal grants and assistance; and bringing coherence to Federal strategic planning. | |

| Department of Agriculture | Environmental Quality Incentive Program | Incentives | yes | All working agricultural lands | Provides assistance to agricultural producers in a manner that will promote agricultural production and environmental quality as compatible goals, Applies to all agriculture, not restricted to bioenergy crops. Applies to establishment of new practices. | Since EQIP began in 1997, USDA has entered into 117,625 contracts, enrolled more than 51.5 million acres into the program, and obligated nearly USD 1.08 billion to help producers advance stewardship on working agricultural land. |

| Department of Agriculture | Conservation Security Program | Incentives | yes | Working agricultural lands in selected watersheds | A voluntary conservation program that supports ongoing stewardship of private agricultural lands by providing payments for maintaining and enhancing natural resources. Applies to all agriculture, not restricted to energy crops. Can apply to existing practices. | Since its inception in 2004, 19,400 farms and ranches representing 15,800,000 acres in 280 different watersheds have been enrolled. In 2005, CSP made payments of USD 202 million |

| Department of Agriculture | Conservation Reserve Program | Incentives | Yes | Highly erodible soils and target conservation areas | Provides incentives to prevent expansion of agriculture, including bioenergy crops, into marginal lands for agriculture that are prone to soil erosion. Applies to all agriculture, not restricted to bioenergy crops | As of 2005, CRP has a total of 34.9 million acres enrolled that if farmed would be very susceptible to erosion and runoff. CRP payments for land retirement in 2005 totaled USD 1.79 billion. |

| Department of Agriculture | Woody Biomass Utilization 2005 Grant Program, Public Law 108–447 & Public Law 108–148 | grants | yes | State foresters and local communities | ||

| Department of Agriculture | Biomass for small-scale heat and power | R&D | yes | Bioenergy users | ||

| Department of Agriculture | Wetlands Reserve Program | Incentives | yes | Restoration of wetlands marginal for agriculture | Provides incentives to prevent expansion of agriculture, including bioenergy crops, into marginal lands for agriculture that have a high environmental value. | |

| Environmental Protection Agency | Energy Act 2005. Section 211 of the Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. 7545) amended | Policy/Regulation | yes | Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) Refineries, blenders, distributors, and importers | Renewable Fuel—For the purpose of subparagraph (A), the applicable volume of renewable fuel for the calendar years 2006 (4 billion gallons of renewable fuel through 2012 with 7.5 billion gallons of renewable fuel. | |

| Department of Energy, Department of Agriculture, Department of Interior, and Environmental Protection Agency | Energy Act 2007. Sec. 201, Definitions | Legislation | Yes | Government and producers of biodiesel and fuels grade ethanol | (I) Renewable Biomass—The term ‘renewable biomass’ means each of the following: (i) Planted crops and crop residue harvested from agricultural land cleared or cultivated at any time prior to the enactment of this sentence that is either actively managed or fallow, and non-forested. (ii) Planted trees and tree residue from actively managed tree plantations on non-federal land cleared at any time prior to enactment of this sentence, including land belonging to an Indian tribe or an Indian individual, that is held in trust by the United States or subject to a restriction against alienation imposed by the United States. (iii) Animal waste material and animal byproducts. (iv) Slash and pre-commercial thinnings that are from non-federal forestlands, including forestlands belonging to an Indian tribe or an Indian individual, that are held in trust by the United States or subject to a restriction against alienation imposed by the United States, but not forests or forestlands that are ecological communities with a global or State ranking of critically imperiled, imperiled, or rare pursuant to a State Natural Heritage Program, old growth forest, or late successional forest. (v) Biomass obtained from the immediate vicinity of buildings and other areas regularly occupied by people, or of public infrastructure, at risk from wildfire. | |

| Environmental Protection Agency | Energy Act 2007. Sec. 202. Renewable Fuel Standard. | Legislation—Targets and Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | (1) Regulations. Amended directing the Administrator to revise the regulations under this paragraph to ensure that transportation fuel sold or introduced into commerce in the United States (except in noncontiguous States or territories), on an annual average basis, contains at least the applicable volume of renewable fuel, advanced biofuel, cellulosic biofuel, and biomass-based diesel, determined in accordance with subparagraph (B) and, in the case of any such renewable fuel produced from new facilities that commence construction after the date of enactment of this sentence, achieves at least a 20 percent reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions compared to baseline lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions. Renewable Fuel—For the purpose of subparagraph (A), the applicable volume of renewable fuel for the calendar years 2006 (4 billion gallons of renewable fuel through 2022 with 36 billion gallons of renewable fuel; 21 billion gallons of advanced biofuel for 2022; and 16 billion gallons of cellulosic biofuel fand 1 billion gallons for biomass diesel for 2022. | USD 250,000,000 |

| Department of Agriculture; Department of Energy; Environmental Protection Agency | Energy Act 2007. Sec. 204. Environmental and Resource Conservation Impacts. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Assess and report to Congress on the impacts to date and likely future impacts of the requirements of Section 211(o) of the Clean Air Act on the following: (1) Environmental issues, including air quality, effects on hypoxia, pesticides, sediment, nutrient and pathogen levels in waters, acreage and function of waters, and soil environmental quality. (2) Resource conservation issues, including soil conservation, water availability, and ecosystem health and biodiversity, including impacts on forests, grasslands, and wetlands. (3) The growth and use of cultivated invasive or noxious plants and their impacts on the environment and agriculture. | |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2007. Sec. 223. Grants for biofuel production research and Development in certain states | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | The Secretary shall provide grants to eligible entities for research, development, demonstration, and commercial application of biofuel production technologies in States with low rates of ethanol production, including low rates of production of cellulosic biomass ethanol, as determined by the Secretary | There are authorized to be appropriated to the Secretary to carry out this section USD 25,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2008 through 2010. |

| Department of Energy | Energy Act 2007. Sec. 234. University based research and development grant Program | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Education Institutions, private industry and environmental interest groups | shall establish a competitive grant program, in a geographically diverse manner, for projects submitted for consideration by institutions of higher education to conduct research and development of renewable energy technologies. | Each grant made shall not exceed USD 2,000,000. |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Section 9001. Definitions | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | (12) Renewable Biomass—The term ‘renewable biomass’ means— (A) materials, pre-commercial thinnings, or invasive species from National Forest System land and public lands (as defined in Section 103 of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (43 U.S.C. 1702)) that— (i) are byproducts of preventive treatments that are removed— (I) to reduce hazardous fuels; (II) to reduce or contain disease or insect infestation; or (III) to restore ecosystem health; (ii) would not otherwise be used for higher value products; and (iii) are harvested in accordance with— (I) applicable law and land management plans; and (II) the requirements for— (aa) old-growth maintenance, restoration, and management direction of paragraphs (2), (3), and (4) of subsection (e) of Section 102 of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (16 U.S.C. 6512); and (bb) large-tree retention of subsection (f) of that section; or (B) any organic matter that is available on a renewable or recurring basis from non-Federal land or land belonging to an Indian or Indian tribe that is held in trust by the United States or subject to a restriction against alienation imposed by the United States, including— (i) renewable plant material, including— (I) feed grains; (II) other agricultural commodities; (III) other plants and trees; and (IV) algae; and (ii) waste material, including— (I) crop residue; (II) other vegetative waste material (including wood waste and wood residues); (III) animal waste and byproducts (including fats, oils, greases, and manure); and (IV) food waste and yard waste. | |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Section 9003 | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Provided for grants covering up to 30% of the cost of developing and building demonstration-scale biorefineries for producing advanced biofuels. | Supported loan guarantees of up to USD 250 million for building commercial scale biorefineries to produce advanced biofuels. The Farm act of 2008 funds the biorefinery program by drawing USD 75 million in funds from the Commodity Credit Corporation for fiscal year 2009, increasing to USD 245 million by 2010. It also authorizes USD 150 million per year in discretionary funds for the program. |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Sec. 9005. Bioenergy Program for Advanced Biofuels | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | The Secretary shall make payments to eligible producers to support and ensure an expanding production of advanced biofuels. | Mandatory Funding. From funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary shall use to carry out this section, to remain available until expended—(A) USD 55,000,000 for fiscal year 2009; (B) USD 55,000,000 for fiscal year 2010; (C) USD 85,000,000 for fiscal year 2011; and (D) USD 105,000,000 for fiscal year 2012. Discretionary Funding. In addition to any other funds made available to carry out this section, there is authorized to be appropriated to carry out this section USD 25,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2009 through 2012. Limitation. Of the funds provided for each fiscal year, not more than 5 percent of the funds shall be made available to eligible producers for production at facilities with a total refining capacity exceeding 150,000,000 gallons per year. | |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Sec. 9008. Biomass Research and Development | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Education Institutions, private industry and environmental interest groups | The Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Energy shall coordinate policies and procedures that promote research and development regarding the production of biofuels and biobased products | Mandatory Funding. Of the funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary of Agriculture shall use to carry out this section, to remain available until expended—(A) USD 20,000,000 for fiscal year 2009; (B) USD 28,000,000 for fiscal year 2010; (C) USD 30,000,000 for fiscal year 2011; and (D) USD 40,000,000 for fiscal year 2012. |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Sec. 9010. Feedstock Flexibility Program for Bioenergy Producers | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | For each of the 2008 through 2012 crops, the Secretary shall purchase eligible commodities from eligible entities and sell such commodities to bioenergy producers for the purpose of producing bioenergy in a manner that ensures that Section 156 of the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act (7 U.S.C. 7272) is operated at no cost to the Federal Government by avoiding forfeitures to the Commodity Credit Corporation | Funding. The Secretary shall use the funds, facilities, and authorities of the Commodity Credit Corporation, including the use of such sums as are necessary, to carry out this section. |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Sec. 9011. Biomass crop assistance program. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | The term ‘eligible land’ includes agricultural and nonindustrial private forest lands (as defined in Section 5(c) of the Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act of 1978 (16 U.S.C. 2103a(c))). The Secretary shall establish and administer a Biomass Crop Assistance Program to (1) support the establishment and production of eligible crops for conversion to bioenergy in selected BCAP project areas; and (2) assist agricultural and forest land owners and operators with collection, harvest, storage, and transportation of eligible material for use in a biomass conversion facility | Funding. Of the funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary shall use to carry out this section such sums as are necessary for each of fiscal years 2008 through 2012 |

| Department of Agriculture | Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Sec. 9012. Forest Biomass for Energy | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Education Institutions, private industry and environmental interest groups | The Secretary, acting through the Forest Service, shall conduct a competitive research and development program to encourage use of forest biomass for energy. | Authorization of Appropriations. There is authorized to be appropriated to carry out this section USD 5,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2009 through 2012. |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2014. Sec. 9002. Biobased Markets Program | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Establish a targeted biobased-only procurement requirement under which the procuring agency shall issue a certain number of biobased-only contracts when the procuring agency is purchasing products, or purchasing services that include the use of products, that are included in a biobased product category designated by the Secretary Promote biobased products, including forest products, that apply an innovative approach to growing, harvesting, sourcing, procuring, processing, manufacturing, or application of biobased products regardless of the date of entry into the marketplace The Secretary shall conduct a study to assess the economic impact of the biobased products industry. Forest Products Laboratory Coordination. In determining whether products are eligible for the ‘USDA Certified Biobased Product’ label, the Secretary (acting through the Forest Products Laboratory) shall provide appropriate technical and other assistance to the program and applicants for forest products | Mandatory Funding. Of the funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary shall use to carry out this section USD 3,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2018. Discretionary Funding. There is authorized to be appropriated to carry out this section USD 2,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2018. |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2014. Sec. 9003. Biorefinery Assistance. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | In approving loan guarantee applications, the Secretary shall ensure that, to the extent practicable, there is diversity in the types of projects approved for loan guarantees to ensure that as wide a range as possible of technologies, products, and approaches are assisted. Subject to subparagraph (B), of the funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary shall use for the cost of loan guarantees under this section, to remain available until expended. (B) Biobased Product Manufacturing. Of the total amount of funds made available for fiscal years 2014 and 2015 under subparagraph (A), the Secretary may use for the cost of loan guarantees under this section not more than 15 percent of such funds to promote biobased product manufacturing. | (i) USD 100,000,000 for fiscal year 2014; and (ii) USD 50,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2015 and 2016. For each of fiscal years 2009 through 2013′’ and inserting USD 75,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2018′ |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2014. Sec. 9008. Biomass Research and Development | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Education Institutions, private industry and environmental interest groups | Promotes research and development activities for development of new and emerging bioenergy technologies and processes for production of bio-based fuels, including biomass. Promotes new and emerging technologies for use in the production of biofuels and bioenergy | USD 3,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2017.; and USD 20,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2018 |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2014. Sec. 9010. Biomass crop assistance program. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | The Secretary shall establish and administer a Biomass Crop Assistance Program to (1) support the establishment and production of eligible crops for conversion to bioenergy in selected BCAP project areas; and (2) assist agricultural and forest land owners and operators with collection, harvest, storage, and transportation of eligible material for use in a biomass conversion facility. The term ‘eligible material’ means renewable biomass harvested directly from the land, including crop residue from any crop that is eligible to receive payments under title I of the Agricultural Act of 2014 or an amendment made by that title. (B) Inclusions. The term ‘eligible material’ shall only include (i) eligible material that is collected or harvested by the eligible material owner. (I) directly from (aa) National Forest System; (bb) Bureau of Land Management land; (cc) non-Federal land; or (dd) land owned by an individual Indian or Indian tribe that is held in trust by the United States for the benefit of the individual Indian or Indian tribe or subject to a restriction against alienation imposed by the United States; (II) in a manner that is consistent with (aa) a conservation plan; (bb) a forest stewardship plan; or (cc) a plan that the Secretary determines is equivalent to a plan described in item (aa) or (bb) and consistent with Executive Order 13112 (42 U.S.C. 4321 note; relating to invasive species); (ii) if woody eligible material, woody eligible material that is produced on land other than contract acreage that (I) is a byproduct of a preventative treatment that is removed to reduce hazardous fuel or to reduce or contain disease or insect infestation; and (II) if harvested from Federal land, is harvested in accordance with Section 102(e) of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (16 U.S.C. 6512(e)); and (iii) eligible material that is delivered to a qualified biomass conversion facility to be used for heat, power, biobased products, research, or advanced biofuels. | (1) In General. Of the funds of the Commodity Credit Corporation, the Secretary shall use to carry out this section USD 25,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2014 through 2018. (2) Collection, Harvest, Storage, and Transportation Payments. Of the amount made available under paragraph (1) for each fiscal year, the Secretary shall use not less than 10 percent, nor more than 50 percent, of the amount to make collection, harvest, transportation, and storage payments under subsection (d)(2). (3) Technical Assistance. (A) In General. Effective for fiscal year 2014 and each subsequent fiscal year, funds made available under this subsection shall be available for the provision of technical assistance with respect to activities authorized under this section |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2014. Sec. 9012. Community Wood Energy Program. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Grant Program. Section 9013(b)(1) of the Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 (7 U.S.C. 8113(b)(1)) is amended. Grants of up to USD 50,000 to biomass consumer cooperatives for the purpose of establishing or expanding biomass consumer cooperatives that will provide consumers with services or discounts relating to (i) the purchase of biomass heating systems; (ii) biomass heating products, including wood chips, wood pellets, and advanced biofuels; or (iii) the delivery and storage of biomass of heating products. | |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2018. Sec. 9002. Biobased Markets Program | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Not later than 1 year after the date of enactment of this subsection, the Secretary shall establish guidelines for an integrated process under which biobased products may be, in 1 expedited approval process. (A) determined to be eligible for a Federal procurement preference under subsection (a); and (B) approved to use the ‘USDA Certified Biobased Product’ label under subsection (b). | USD 3,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2019 through 2023 |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2018. Sec. 9003. Biorefinery Assistance. | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Section 9003 of the Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 (7 U.S.C. 8103) is amended (1) in subsection (b)(3) (A) in subparagraph (A), by striking ‘‘produces an advanced biofuel; and and inserting the following: ‘‘produces any 1 or more, or a combination, of (i) an advanced biofuel; (ii) a renewable chemical; or (iii) a biobased product; and; and (B) in subparagraph (B), by striking ‘‘produces an advanced biofuel.’’ and inserting the following: ‘’produces any 1 or more, or a combination, of (i) an advanced biofuel; (ii) a renewable chemical; or (iii) a biobased product.’ | And inserting a semicolon; and (iii) by adding at the end the following: (iii) USD 50,000,000 for fiscal year 2019; and (iv) USD 25,000,000 for fiscal year 2020.’’; and (B) in paragraph (2), by striking ‘‘2018′’ and inserting ‘‘2023′ |

| Department of Agriculture | Agricultural Act of 2018. Sec. 9010. Biomass Crop Assistance Program | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Producers of Biodiesel and fuel grade ethanol from energy crops, oil seed, or vegetable oils that produce bioenergy | Algae material was added as eligible. | This section USD 25,000,000 for each of fiscal years 2019 through 2023. |

| Department of Agriculture and Department of Interior | Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, 2021. Sec. 40803. Wildfire Risk Reduction | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Government | (b) Treatment—Of the Federal land or Indian forest land or rangeland that has been identified as having a very high wildfire hazard potential, the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service, shall, by not later than 30 September 2027, conduct restoration treatments and improve the Fire Regime Condition Class of 10,000,000 acres. (c) ACTIVITIES—Of the amounts made available under subsection (a) for the period of fiscal years 2022 through 2026 (10) USD 100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of Agriculture for collaboration and collaboration-based activities, including facilitation, certification of collaboratives, and planning and implementing projects under the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program established under Section 4003 of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 (16 U.S.C. 7303) in accordance with subsection (e); (11) USD 500,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture— (A) for— (i) conducting mechanical thinning and timber harvesting in an ecologically appropriate manner that maximizes the retention of large trees, as appropriate for the forest type, to the extent that the trees promote fire-resilient stands; or (ii) precommercial thinning in young growth stands for wildlife habitat benefits to provide subsistence resources; and (B) of which— (i) USD 100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of the Interior; and (ii) USD 400,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of Agriculture; (15) USD 200,000,000 shall be made available for contracting or employing crews of laborers to modify and remove flammable vegetation on Federal land and for using materials from treatments to the extent practicable, to produce biochar and other innovative wood products, including through the use of existing locally based organizations that engage young adults, Native youth, and veterans in service projects, such as youth and conservation corps, of which— (A) USD 100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of the Interior; and (B) USD 100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary of Agriculture; | (a) Authorization of Appropriations—There is authorized to be appropriated to the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service, for the activities described in subsection (c), USD 3,369,200,000 for the period of fiscal years 2022 through 2026. |

| Department of Agriculture | Sec. 40804. Ecosystem Restoration | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Government | (2) USD 160 million for FS to provide funds to States and Tribes for implementing restoration projects on federal land through the Good Neighbor Authority (3) USD 400 million for USDA to provide financial assistance to facilities that purchase and process byproducts from ecosystem restoration projects, based on a ranking of the need to remove the vegetation and whether the presence of a new or existing wood product facility would substantially reduce the cost of removing the material. Furthermore, encourages the spending of other federal funds based on the ranking criteria for removal of vegetation and presence of a wood processing facility or forest worker is seeking to conduct restoration treatment work on or in close proximity to the unit. | (a) Authorization of Appropriations—There is authorized to be appropriated to the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service, for the activities described in subsection (b), USD 2,130,000,000 for the period of fiscal years 2022 through 2026. |

| Sec. 40808. Joint Chiefs Landscape Restoration Partnership Program | Legislation—Mandates | Yes | Government | Codifies the Joint Chiefs Landscape Restoration Partnership Program, includes criteria for evaluation of proposals, and authorizes the appropriation of USD 90 million for each of fiscal years 2022 and 2023, with not less than 40 percent allocated to carry out eligible activities through NRCS and not less than 40 percent allocated to carry out eligible activities through the Forest Service. | ||

References

- Galik, C.S.; Benedum, M.E.; Kauffman, M.; Becker, D.R. Opportunities and barriers to forest biomass energy: A case study of four US states. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlener, R.; Vögtli, S. Diffusion of bioenergy in urban areas: A socio-economic analysis of the Swiss wood-fired cogeneration plant in Basel. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.F.; Thor, E.C.; Elsner, G.H. Wildland Planning Glossary. In General Technical Report PSW-13; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1976; 252p. [Google Scholar]

- Grebner, L.D.; Bettinger, P.; Jacek, P.; Siry, P.J. Chapter 15-Forest Policies and External Pressures. In Introduction to Forestry and Natural Resources; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 359–383. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123869012000154?via%3Dihub#bib54 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Cubbage, W.F.; O’Laughlin, J.; Peterson, M.N. Natural Resource Policy; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2017; 505p, Available online: https://vdoc.pub/download/natural-resource-policy-4qccj9ed7u40 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Ali, M. Chapter 8: Assessment of Policy Instruments. In Sustainability Assessment Context of Resource and Environmental Policy; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.R.; Lee, C. State Woody Biomass Utilization Policies. In Staff Paper Series No. 199; Department of Forest Resources, College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences, University of Minnesota: Falcon Heights, MN, USA, 2008; 203p, Available online: https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/107766 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Lucas, P.U.; Gamborg, C.; Lund, T.B. Sustainability concerns are key to understanding public attitudes toward woody biomass for energy: A survey of Danish citizens. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergin, D. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1991; 945p, Available online: http://arnosworld.free.fr/sustainability/Daniel%20Yergin%20-%20The%20Prize%20-%20The%20Epic%20Quest%20for%20Oil,%20Money,%20&%20Power%20(1991).pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Aguilar, X.F.; Song, N.; Shifley, S. Review of consumption trends and public policies promoting woody biomass as an energy feedstock in the US. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011, 35, 3708–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Power Association. The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978. 2020. 4p. Available online: https://www.publicpower.org/system/files/documents/PURPA%20-%20January%202020.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Beck, F.; Martinot, E. Renewable Energy Policies and Barriers. In Encyclopedia of Energy; Cleveland, C.J., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Available online: https://biblioteca.cejamericas.org/bitstream/handle/2015/3308/Renewable_Energy_Policies_and_Barriers.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Bracmort, K. Biomass: Comparison of Definitions in Legislation. Congressional Research Service Report; 2019; 13p. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R40529/23 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Wood Energy eXtension Community of Practice. Federal Policies and Incentives Promoting Woody Biomass Production and Utilization. Posted September 2019. 2021. Available online: https://wood-energy.extension.org/federal-policies-and-incentives-promoting-woody-biomass-production-and-utilization/#Grants_for_Forest_Biomass_Utilization (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Rahmani, M.; Hodges, W.A.; Monroe, C.M. Federal Policies and Incentives. Wood to Energy Fact Sheet. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Florida. 2007. Available online: http://sfrc.ufl.edu/extension/ee/woodenergy/files/supplementalreading/Federal%20Policies%20and%20Incentives.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- National Association of Conservation Districts. Woody Biomass Desk Guide andToolkit. 2021. Available online: https://www.nacdnet.org/general-resources/district-guides/woody-biomass-desk-guide-toolkit/#reference (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Code of Federal Regulations. Title 36.—Parks, Forests, and Public Property. Chapter II Forest Service, Department of Agriculture. Part 223. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-36/chapter-II/part-223 (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Aguilar, X.F.; Saunders, A. Policy instruments promoting wood-to-energy uses in the continental United States. J. For. 2010, 108, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, X.F.; Saunders, A. Attitudes toward policy instruments promoting wood-to-energy initiatives in the United States. South. J. Appl. For. 2011, 35, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.R.; Moseley, C.; Lee, C. A supply chain analysis framework for assessing state-level forest biomass utilization policies in the United States. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011, 35, 1429–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebers, A.; Malmsheimer, W.A.; Volk, A.T.; Newman, H.D. Inventory and classification of United States federal and state forest biomass electricity and heat policies. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 84, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.; Becker, D.; Kudrna, J.; Moseley, C. Does policy matter? The role of policy systems in forest bioenergy development in the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 75, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, S.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Moseley, C.; McCaffery, S. Woody Biomass Use Trends, Barriers, and Strategies: Perspectives of US Forest Service Managers. J. For. 2012, 110, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.R.; Anderson, N.M.; Daugaard, E.D.; Naughton, T.H. Technoeconomic and policy drivers of project performance for bioenergy alternatives using biomass from beetle-killed trees. Energies 2018, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.D.; Anderson, N.M.; Naughton, H.T.; Mullan, K. Economic and policy factors driving adoption of institutional woody biomass heating systems in the U.S. Energy Econ. 2018, 69, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hodges, D.G.; Young, T.M. Woody biomass utilization policies: State rankings for the U.S. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 21, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. 2016 Billion-Ton Report: Advancing Domestic Resources for a Thriving Bioeconomy, Volume 1: Economic Availability of Feedstocks; Langholtz, M.H., Stokes, B.J., Eaton, L.M., Eds.; ORNL/TM-2016/160; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2016; 448p. Available online: https://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/Files/Pub62368.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Sahoo, K.; Bilek, E.M.; Bergman, R.; Kizha, A.R.; Mani, S. Economic analysis of forest residues supply chain options to produce enhanced-quality feedstocks. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 2019, 13, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest2Market. Renewable Biomass–RFS Wood Biomass White Paper. 2019. Available online: https://www.forest2market.com/?hsLang=en-us (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Congressional Research Service. Biomass: Comparison of Definitions in Legislation; CRS Report R40529; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; 16p. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R40529.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Alternative Fuels Data Center. Renewable Fuel Standard. 2022. Available online: https://afdc.energy.gov/laws/RFS#:~:text=The%20Renewable%20Fuel%20Standard%20(RFS,Act%20of%202007%20(EISA) (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Fuels Registration, Reporting, and Compliance Help. What materials from non-federal forestlands meet the definition of renewable biomass in RFS? 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/fuels-registration-reporting-and-compliance-help/what-materials-non-federal-forestlands-meet (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- White, M.E. Woody Biomass for Bioenergy and Biofuels in the United States—A Briefing Paper. In General Technical Report PNW-GTR-825; Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2010; 56p. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. White House. FACT SHEET: Biden Administration Advances the Future of Sustainable Fuels in American Aviation. 2021. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/09/fact-sheet-biden-administration-advances-the-future-of-sustainable-fuels-in-american-aviation/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- U.S. Code. Title 42—The Public Health 110 and Welfare. Chapter 85—Air Pollution Prevention and Control. 42 USC 7545: Regulation of fuels. Office of the Law Revision Counsel. 2022. Available online: http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title42-section7545&num=0&edition=prelim (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency (DSIRE). Renewable Portfolio Standards and Clean Energy Standards (Updated 2020). NC Clean Energy Technology Center, 2020. Available online: http://www.dsireusa.org/resources/detailed-summary-maps/ (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agricultures. Forest Service Research and Development Bioenergy and Biobased Products Strategic Direction 2009–2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; 10p. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/research/docs/priority/bioenergy-strategic-direction.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Financial Incentives. Cash payments or reduced taxes can be an effective governmental tool to achieve policy objectives. | Tax incentives Sales tax incentives. Establishes reduction or exemption from state sales tax on the purchase of qualifying equipment for harvesting, transportation, and manufacturing or processing of biomass. Corporate/production tax incentives. Deductions or exemptions from taxes paid by businesses for installing certain types of biomass manufacturing systems. They may also include production tax credits paid for the volume of forest biomass used in production or for the amount of energy produced. Personal tax incentives. Provides income tax credits and deductions most commonly related to the installation of certain types of renewable energy systems. Property tax incentives. Exemptions, exclusions, and credits for the use of property (including equipment) used for the sitting of qualifying manufacturing facilities or the transport of biomass. Financing and contracting Business recruitment is used to promote economic development and job creation by offering specific incentives like property tax credits to locate in investment zones or in a business incubator, tax exemptions on equipment purchased or individuals employed, and grants for investing in certain types of technology. Recruitment incentives are generally temporary measures to support emerging industries. Bonds allow state and local governments to raise money by borrowing to support construction of biomass utilization facilities, including the installation of wood boilers to heat schools and industrial facilities. The bonding authority may be reimbursed using the savings resulting from the installation of projects. Loans provide financing for the purchase of qualifying equipment for harvesting biomass, transportation, and processing or remanufacturing. Micro-loans, low-interest, and zero- interest loans may be available to residential, commercial, industrial, transportation, public and nonprofit sectors. Procurement and contracting requires certain types of products be purchases from qualifying sources or that certain types of contractors be used in biomass processing and delivery. By issue of Executive Order, city ordinance, or state legislation, certain biomass products may be required for use in heating, construction, or operating vehicles or equipment. Financial incentives in the form of tax credits, grants, and loans may be used to encourage procurement/contracting practices where it is not mandated. Subsidies and grants Cost share programs. Designed to reduce the purchase price or operations cost of equipment used for biomass harvesting, transportation, or manufacturing. The cost of operations may also be reduced through a waiver of fees, or supplemental resources provided to pay for biomass harvesting or procurement. Grant programs. Encourage the use and development of certain types of technologies or programs aimed at biomass utilization. Grants are typically available to commercial, industrial, community, and government sectors on a competitive basis to purchase equipment, support research, development, or demonstration projects, and to support product commercialization and marketing. Rebate programs. Offered by state or local governments and utilities to promote the purchase or installation of qualifying biomass manufacturing and processing systems. |

| Rules and regulations. Use of the legal system to regulate behavior is a common policy tool used by governments, possibly requiring that people engage in particular activities. | Renewable energy standards. Require utility companies to use renewable energy to account for a certain percentage of their retail electricity sales or generation. This category includes renewable energy goals that establish nonbinding goals for renewable energy production; interconnection standards governing how energy producers connect to the grid; consumer green power programs offering the option of buying electricity generated from renewable resources; net metering or buy-back of excess power generated from renewable sources; and public benefit funds that set aside utility dollars for renewable energy development. Equipment certification. Establishes standards for the efficiency or quality of equipment used to process or manufacture biomass (e.g., wood pellet burners and biomass boilers). |

| Provision of services. State governments routinely offer numerous services to landowners. States provide fire control, technical assistance in land management, and market information. | Education and consultation Technical assistance. Establishes local or state programs to coordinate research on biomass utilization, disseminate technical information, and assist with business planning and grant writing. Other activities may include the creation of business planning tools, organize outreach to potential businesses, or to coordinate existing service programs. Training programs. Education courses or certificates offered to businesses, employees, agency personnel, and others involved in biomass harvesting and use in which development of technical expertise is the objective. |

| Public attitudes Public acceptance of woody biomass used for bioenergy and bioproducts. | Policy implications Perceptions of stakeholders, policy makers, and industry about climate change mitigation, sustainability, biodiversity changes, recreation, bioenergy, and rural economies are critical to increased use of woody biomass. Training programs, increased communication, and education used to involve a wider audience. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Page-Dumroese, D.S.; Franco, C.R.; Archuleta, J.G.; Taylor, M.E.; Kidwell, K.; High, J.C.; Adam, K. Forest Biomass Policies and Regulations in the United States of America. Forests 2022, 13, 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091415

Page-Dumroese DS, Franco CR, Archuleta JG, Taylor ME, Kidwell K, High JC, Adam K. Forest Biomass Policies and Regulations in the United States of America. Forests. 2022; 13(9):1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091415

Chicago/Turabian StylePage-Dumroese, Deborah S., Carlos Rodriguez Franco, James G. Archuleta, Marcus E. Taylor, Kraig Kidwell, Jeffrey C. High, and Kathleen Adam. 2022. "Forest Biomass Policies and Regulations in the United States of America" Forests 13, no. 9: 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091415