Exploring a New O3 Index as a Proxy for the Avoidance/Tolerance Capacity of Forest Species to Tolerate O3 Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Forest Monitoring Network

2.2. Ozone FACE Facility

2.3. Calculation of O3 Indices: AOT40, POD1 and LIF

2.4. Stomatal O3 Flux Modelling

2.5. Calculation of Leaf Mass per Area (LMA)

2.6. Surveys of O3 Visible Foliar Injury

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Conditions and Ozone Concentrations

3.1.1. MOTTLES Sites

3.1.2. FACE Experiments

3.2. Leaf Mass per Area

3.2.1. MOTTLES Sites

3.2.2. FACE Experiments

3.3. Ozone Visible Foliar Injury at LESS, ITP and FACE

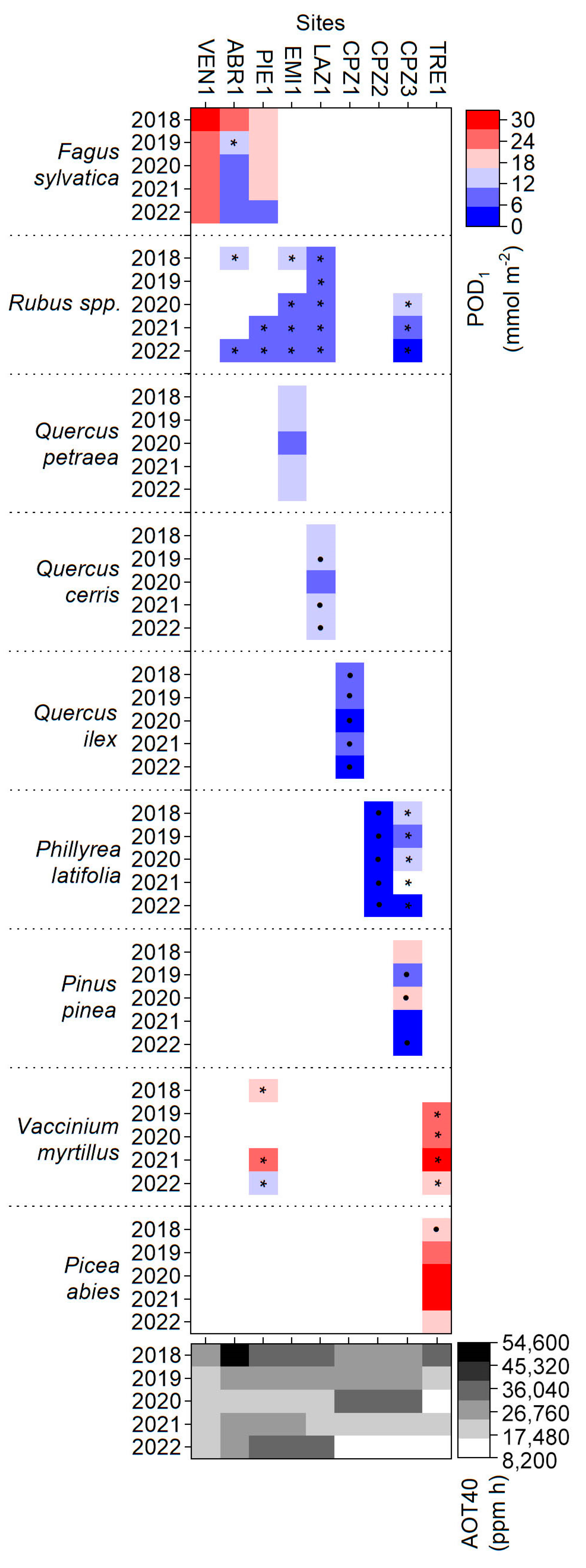

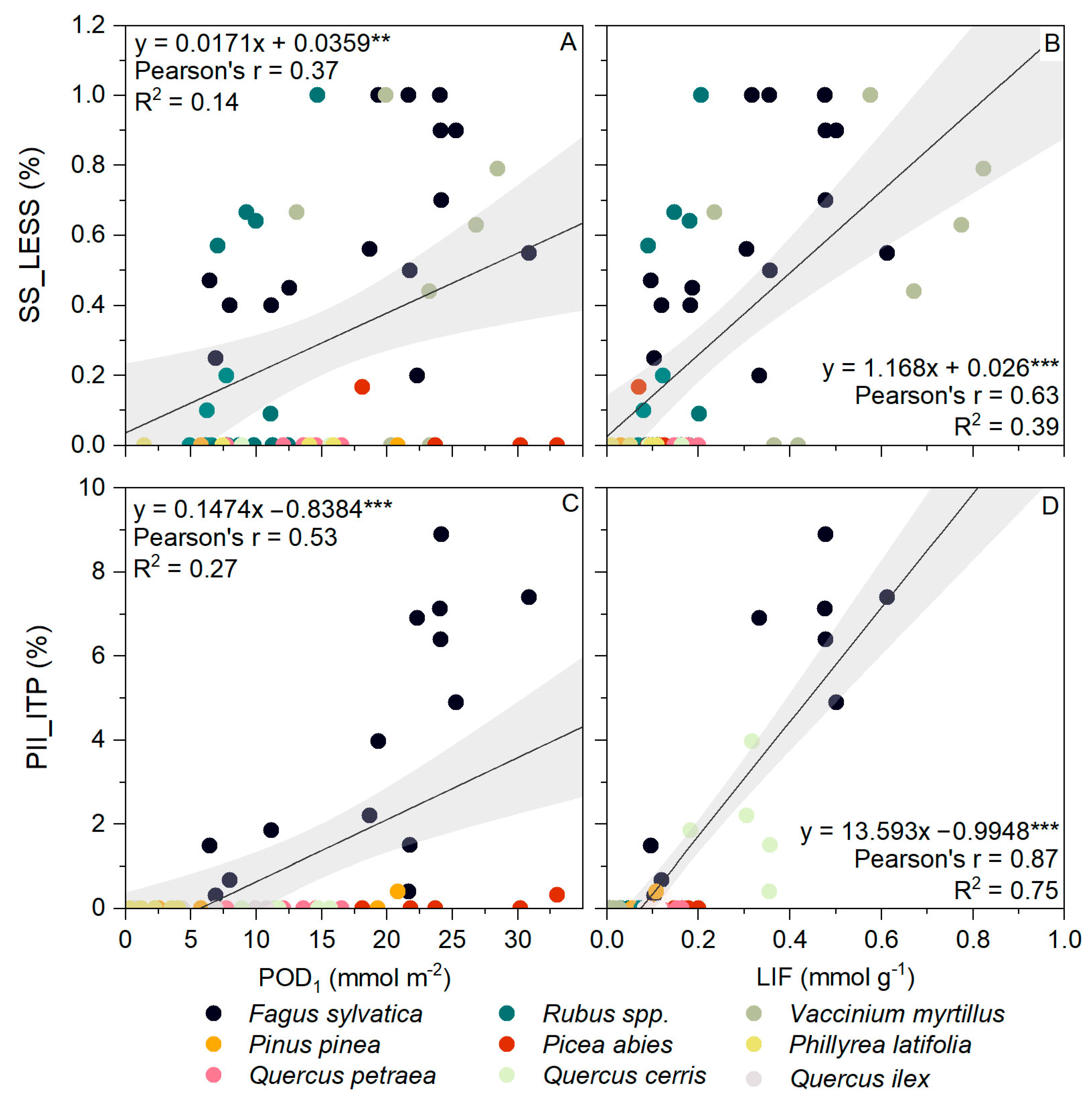

3.4. AOT40 and POD1 versus Visible Foliar Injury

3.5. LIF versus Visible Foliar Injury

4. Discussion

4.1. Different Sensitivity to O3 among Species according to Visible Foliar Injury

4.2. Which Is the Best Index for Ozone Visible Foliar Injury

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cotrozzi, L.; Pellegrini, E.; Nali, C.; Lorenzini, G. Climate change, ozone and plant life. Agrochimica 2019, 62, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, S.P.; Das, A.B.; Gurung, C.; Ghosh, C. Effects of Ozone on Plant Health and Environment: A Mini Review. Res. Jr. Agril. Sci. 2022, 13, 612–619. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lin, W.; Xu, W.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Q.; et al. Long-term changes of regional ozone in China: Implications for human health and ecosystem impacts. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P. Ground-level ozone over time: An observation-based global overview. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 19, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleux, F.; Solmon, F.; Giorgi, F. Increase in summer European ozone amounts due to climate change. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 7577–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.J.; Archibald, A.T.; Bowman, K.W.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Naik, V.; Stevenson, D.S.; Tilmes, S.; Voulgarakis, A.; Wild, O.; Bergmann, D.; et al. Pre-industrial to end 21st century projections of tropospheric ozone from the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 2063–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Anav, A.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. Projected global ground-level ozone impacts on vegetation under different emission and climate scenarios. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 12177–12196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pay, M.T.; Gangoiti, G.; Guevara, M.; Napelenok, S.; Querol, X.; Jorba, O.; Pérez García-Pando, C. Ozone source apportionment during peak summer events over southwestern Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 5467–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grulke, N.E.; Heath, R.L. Ozone effects on plants in natural ecosystems. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 12–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberson, L. Effects of ozone on agriculture, forests and grasslands. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378, 20190327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Mills, G. Ozone pollution: Impacts on Carbon Sequestration in Europe; NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Lancaster, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agathokleous, E.; Feng, Z.; Oksanen, E.; Sicard, P.; Wang, Q.; Saitanis, C.J.; Araminiene, V.; Blande, J.D.; Hayes, F.; Calatayud, V.; et al. Ozone affects plant, insect, and soil microbial communities: A threat to terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshika, Y.; Fares, S.; Savi, F.; Gruening, C.; Goded, I.; De Marco, A.; Sicard, P.; Paoletti, E. Stomatal conductance models for ozone risk assessment at canopy level in two Mediterranean evergreen forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 234, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshika, Y.; Carrari, E.; Mariotti, B.; Martini, S.; De Marco, A.; Sicard, P.; Paoletti, E. Flux-Based Ozone Risk Assessment for a Plant Injury Index (PII) in Three European Cool-Temperate Deciduous Tree Species. Forests 2020, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, C.; Anav, A.; De Marco, A.; Sicard, P.; Vitale, M. A multi-sites analysis on the ozone effects on Gross Primary Production of European forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 556, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisner, C.P.; Ainsworth, E.A. Quantifying the effects of ozone on plant reproductive growth and development. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, G.; Pleijel, H.; Malley, C.S.; Sinha, B.; Cooper, O.R.; Schultz, M.G.; Neufeld, H.S.; Simpson, D.; Sharps, S.; Feng, Z.; et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Present–day tropospheric ozone distribution and trends relevant to vegetation. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2018, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, V.; Cerveró, J.; Sanz, M.J. Foliar, Physiological and growth responses of four maple species exposed to ozone. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 185, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Calatayud, V.; Gao, F.; Uddling, J.; Feng, Z. Differences in ozone sensitivity among woody species are related to leaf morphology and antioxidant levels. Tree Physiol. 2016, 36, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, B.B.; Alves, E.S.; Marabesi, M.A.; Ribeiro de Souza, S.; Schaub, M.; Vollenweider, P. Ozone affects leaf physiology and causes injury to foliage of native tree species from the tropical Atlantic Forest of southern Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicard, P.; Hoshika, Y.; Carrari, E.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. Testing visible ozone injury within a Light Exposed Sampling Site as a proxy for ozone risk assessment for European forests. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, B.B.; Carrari, E.; Dalstein-Richier, L.; Sicard, P.; Leca, S.; Badea, O.; Pitar, D.; Shashikumar, A.; Cirani, M.L.; Paoletti, E.; et al. Bridging experimental and monitoring research for visible foliar injury as bio-indicator of ozone impacts on forests. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2144466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 21st May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 152, 1–44.

- Paoletti, E.; Alivernini, A.; Anav, A.; Badea, O.; Carrari, E.; Chivulescu, S.; Conte, A.; Ciriani, M.L.; Dalstein-Richer, L.; De Marco, A.; et al. Toward stomatal–flux based forest protection against ozone: The MOTTLES approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, A.; Proietti, C.; Anav, A.; Ciancarella, L.; D'Elia, I.; Fares, S.; Fornasier, M.F.; Fusaro, L.; Gualtieri, M.; Manes, F.; et al. Impacts of air pollution on human and ecosystem health, and implications for the National Emission Ceilings Directive: Insights from Italy. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F. Functional leaf traits, plant communities and acclimation processes in relation to oxidative stress in trees: A critical overview. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 2727–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Büker, P.; Pleijel, H.; Emberson, L.; Karlsson, P.E.; Uddling, J. A unifying explanation for variation in ozone sensitivity among woody plants. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.P.; Rassat, P.; Berrang, P.; Karnosky, D.F. Relationships between leaf anatomy and ozone sensitivity of Fraxinus pennsylvanica marsh. and Prunus serotina Ehrh. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1992, 32, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, G.; Hecke, K.; Tausz, M.; Matyssek, R. Foliage type specific susceptibility to ozone in Picea abies, Pinus cembra and Larix decidua at treeline: A synthesis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 90, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, E.; Materassi, A.; Fasano, G.; Hoshika, Y.; Carriero, G.; Silaghi, D.; Badea, O. A new-generation 3D ozone FACE (free air controlled exposure). Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLRTAP, 2017. Mapping Critical Levels for Vegetation, Chapter III of Manual on Methodologies and Criteria for Modelling and Mapping Critical Loads and Levels and Air Pollution Effects, Risks and Trends. UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution. Available online: www.icpmapping.org (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Paoletti, E.; Sicard, P.; Hoshika, Y.; Fares, S.; Badea, O.; Pitar, D.; Popa, I.; Anav, A.; Barbara, B.B.; De Marco, A. Towards long-term sustainability of stomatal ozone flux monitoring at forest sites. Sustain. Horiz. 2022, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P.G. Interpretation of variations in leaf water potential and stomatal conductance found in canopies in field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1976, 273, 593–610. [Google Scholar]

- Anav, A.; De Marco, A.; Proietti, C.; Alessandri, A.; Dell’Aquila, A.; Cionni, I.; Friedlingstein, P.; Khvorostyanov, D.; Menut, L.; Paoletti, E.; et al. Comparing concentration-based (AOT40) and stomatal uptake (PODY) metrics for ozone risk assessment to European forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1608–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshika, Y.; Osada, Y.; De Marco, A.; Penuelas, J.; Paoletti, E. Global diurnal and nocturnal parameters of stomatal conductance in woody plants and major crops. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easlon, H.M.; Bloom, A.J. Easy Leaf Area: Automated digital image analysis for rapid and accurate measurement of leaf area. Appl. Plant Sci. 2014, 2, 1400033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, M.; Calatayud, V.; Ferretti, M.; Brunialti, G.; Lövblad, G.; Krause, G.; Sanz, M.J. Part VIII: Monitoring of Ozone Injury. In UNECE ICP Forests Programme Coordinating Centre (Ed) Manual on Methods and Criteria for Harmonized Sampling, Assessment, Monitoring and Analysis of the Effects of Air Pollution on Forests; Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems: Eberswalde, Germany, 2016; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti, E.; Ferrara, A.M.; Calatayud, V.; Cerveró, J.; Giannetti, F.; Sanz, M.J.; Manning, W.J. Deciduous shrubs for ozone bioindication: Hibiscus syriacus as an example. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerosa, G.; Marzuoli, R.; Bussotti, F.; Pancrazi, M.; Ballarin-Denti, A. Ozone sensitivity of Fagus sylvatica and Fraxinus excelsior young trees in relation to leaf structure and foliar ozone uptake. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 125, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, P.; Günthardt-Goerg, M.S.; Menard, T.; Baumgarten, M.; Matyssek, R.; Schaub, M. Macro- and microscopic leaf injury triggered by ozone stress in beech foliage (Fagus sylvatica L). Ann. For. Sci. 2019, 76, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderHeyden, D.; Skelly, J.; Innes, J.; Hug, C.; Zhang, J.; Landolt, W.; Bleuler, P. Ozone exposure thresholds and foliar injury on forest plants in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 111, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, E. Ozone impacts on Mediterranean forests: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 144, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, V.; Cerveró, J.; Calvo, E.; García-Breijo, F.J.; Reig-Armiñana, J.; Sanz, M.J. Responses of evergreen and deciduous Quercus species to enhanced ozone levels. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunn, A.J.; Kozovits, A.R.; Reiter, I.M.; Heerdt, C.; Leuchner, M.; Lutz, C.; Liu, X.; Low, M.; Winkler, J.B. Comparison of ozone uptake and sensitivity between a phytotron study with young beech and a field experiment with adult beech (Fagus sylvatica). Environ. Pollut. 2005, 137, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, T.E.; Matyssek, R. Limitations and perspectives about scaling ozone impacts in trees. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 115, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.G.; Phillips, N.; Bond, B.J. The hydraulic limitation hypothesis revisited. Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 29, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshika, Y.; Cotrozzi, L.; Marchica, A.; Carrari, E.; Lorenzini, G.; Nali, C.; Paoletti, E.; Pellegrini, E. Season-long exposure of bilberry plants to realistic and future ozone pollution improves the nutraceutical quality of fruits. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; De Marco, A.; Carrari, E.; Dalstein-Richier, L.; Hoshika, Y.; Badea, O.; Pitar, D.; Fares, S.; Conte, A.; Popa, I.; et al. Epidemiological derivation of flux-based critical levels for visible ozone injury in European forests. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshika, Y.; Fares, S.; Pellegrini, E.; Conte, A.; Paoletti, E. Water use strategy affects avoidance of ozone stress by stomatal closure in Mediterranean trees–A modelling analysis. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyssek, R.; Bytnerowicz, A.; Karlsson, P.E.; Paoletti, E.; Sanz, M.; Schaub, M.; Wieser, G. Promoting the O3 flux concept for European forest trees. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 146, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Peñuelas, J. Drought-induced oxidative stress in strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) growing in Mediterranean field conditions. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Hernández, A.; Garcia-Plazaola, J.I.; Esteban, R.; Míguez, F.; Artetxe, U.; Gómez-Sagasti, M.T. Photoprotective strategies of Mediterranean plants in relation to morphological traits and natural environmental pressure: A meta-analytical approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, E.; Hoshika, Y.; Dusart, N.; Cotrozzi, L.; Gérard, J.; Nali, C.; Vaultier, M.-N.; Jolivet, Y.; Lorenzini, G.; Paoletti, E. Antioxidative responses of three oak species under ozone and water stress conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussotti, F.; Desotgiu, R.; Cascio, C.; Strasser, R.J.; Gerosa, G.; Marzuoli, R. Photosynthesis responses to ozone in young trees of three species with different sensitivities, in a 2-year open-top chamber experiment (Curno, Italy). Physiol. Plant. 2007, 130, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tosens, T.; Harley, P.C.; Jiang, Y.; Kanagendran, A.; Grosberg, M.; Jaamets, K.; Niinemets, Ü. Glandular trichomes as a barrier against atmospheric oxidative stress: Relationships with ozone uptake, leaf damage, and emission of LOX products across a diverse set of species. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, E. Trichomes form an important first line of defence against adverse environment—New evidence for ozone stress mitigation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1497–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardini, E.; Cristofori, A.; Cristofolini, F.; Nali, C.; Pellegrini, E.; Bussotti, F.; Ferretti, M. Chlorophyll-related indicators are linked to visible ozone symptoms: Evidence from a field study on native Viburnum lantana L. plants in northern Italy. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 39, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Code | Geographic Coordinates | Altitude | Dominant Tree Species | Biome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABR1 | 41.86064 N–13.57482 E | 1500 | Fagus sylvatica | Alpine |

| CPZ1 | 41.70423 N–12.35719 E | 0 | Quercus ilex | Mediterranean |

| CPZ2 | 41.70429 N–12.35732 E | 0 | Phyllirea latifolia | Mediterranean |

| CPZ3 | 41.68068 N–12.39084 E | 0 | Pinus pinea | Mediterranean |

| EMI1 | 44.71998 N–10.20345 E | 200 | Quercus petraea | Continental |

| LAZ1 | 42.82746 N–11.89817 E | 690 | Quercus cerris | Mediterranean |

| PIE1 | 45.68374 N–8.06994 E | 1150 | Fagus sylvatica | Alpine |

| TRE1 | 46.35825 N–11.49405 E | 1800 | Picea abies | Alpine |

| VEN1 | 46.06335 N–12.38810 E | 1100 | Fagus sylvatica | Alpine |

| Site | T (°C) | RH (%) | VPD (kPa) | PAR (μmol m−2 s−1) | SWC (%) | Rainfall (mm) | O3 (ppb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABR1 | 7.67 ± 0.27 | 75.90 ± 2.00 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 374.44 ± 10.67 | 28.90 ± 1.30 | 893.81 ± 157.73 | 52.13 ± 2.08 |

| CPZ * | 16.30 ± 0.25 | 78.60 ± 1.00 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 412.73 ± 14.63 | 13.01 ± 0.84 | 623.95 ± 125.79 | 29.58 ± 2.16 |

| EMI1 | 13.11 ± 1.11 | 74.00 ± 1.00 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 314.36 ± 14.75 | 15.06 ± 0.65 | 793.43 ± 101.91 | 36.50 ± 2.14 |

| LAZ1 | 13.54 ± 0.25 | 73.50 ± 2.00 | 0.52 ± 0.06 | 369.75 ± 11.64 | 17.38 ± 0.71 | 1304.82 ± 328.57 | 45.59 ± 1.53 |

| PIE1 | 8.52 ± 0.96 | 74.20 ± 1.00 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 305.80 ± 11.38 | 27.31 ± 1.79 | 1765.56 ± 363.59 | 50.20 ± 1.09 |

| TRE1 | 5.25 ± 0.55 | 70.50 ± 1.00 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 361.84 ± 21.82 | 39.45 ± 4.41 | 814.65 ± 113.49 | 45.61 ± 2.45 |

| VEN1 | 7.56 ± 0.39 | 86.80 ± 1.00 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 329.30 ± 13.79 | 40.38 ± 0.43 | 1703.58 ± 291.60 | 33.96 ± 0.94 |

| Year | T (°C) | RH (%) | VPD (kPa) | PAR (μmol m−2 s−1) | O3 (ppb) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 1.5 | 2.0 | |||||

| 2016 | 22.90 ± 0.30 | 57.00 ± 3.00 | 1.50 ± 0.08 | 578 ± 13 | 34.7 ± 0.60 | 51.2 ± 0.90 | 66.1 ±1.00 |

| 2017 | 24.50 ± 0.40 | 47.60 ± 1.30 | 1.89 ± 0.08 | 564 ± 16 | 40.3 ± 1.20 | 51.7 ± 1.80 | 63.8 ± 2.30 |

| 2018 | 22.80 ± 0.29 | 55.60 ± 0.83 | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 527 ± 13 | 35.2 ± 0.70 | 53.1 ± 1.10 | 65.2 ± 1.40 |

| 2019 | 23.50 ± 0.35 | 55.10 ± 0.94 | 1.61 ± 0.06 | 548 ± 14 | 38.8 ± 0.90 | 56.2 ± 1.50 | 68.6 ± 1.80 |

| 2020 | 22.10 ± 0.39 | 61.80 ± 1.12 | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 475 ± 17 | 37.5 ± 1.10 | 52.3 ± 1.70 | 73.3 ± 2.30 |

| Year | LESS Site | Fagus sylvatica | Rubus spp. | Vaccinium myrtillus | Picea abies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | VEN1 | 55 | |||

| ABR1 | 20 | ||||

| PIE1 | 56 | ||||

| 2019 | VEN1 | 90 | |||

| ABR1 | 45 | ||||

| PIE1 | 50 | ||||

| TRE1 | 44 | ||||

| 2020 | VEN1 | 70 | |||

| ABR1 | 25 | ||||

| PIE1 | 100 | ||||

| LAZ1 | 10 | ||||

| CPZ3 | 100 | ||||

| TRE1 | 63 | ||||

| 2021 | VEN1 | 90 | |||

| ABR1 | 47 | ||||

| PIE1 | 100 | 9 | |||

| EMI1 | 20 | ||||

| LAZ1 | 57 | ||||

| TRE1 | 79 | ||||

| 2022 | VEN1 | 100 | |||

| ABR1 | 40 | ||||

| PIE1 | 40 | 64.2 | 66.6 | ||

| EMI1 | 66.6 | ||||

| TRE1 | 100 | 16.6 |

| Year | ITP Site | Fagus sylvatica | Pinus pinea | Picea abies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | VEN1 | 7.41 ± 2.15 | ||

| ABR1 | 6.90 ± 3.08 | |||

| PIE1 | 2.20 ± 0.91 | |||

| CPZ3 | 0.44 ± 0.35 | |||

| 2019 | VEN1 | 6.40 ± 3.60 | ||

| PIE1 | 1.50 ± 0.49 | |||

| 2020 | VEN1 | 8.90 ± 1.99 | ||

| ABR1 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | |||

| PIE1 | 3.98 ± 1.63 | |||

| 2021 | VEN1 | 4.90 ± 1.05 | ||

| ABR1 | 1.48 ± 0.56 | |||

| PIE1 | 0.41 ± 0.13 | |||

| TRE1 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | |||

| 2022 | VEN1 | 7.12 ± 1.50 | ||

| ABR1 | 0.68 ± 0.29 | |||

| PIE1 | 1.85 ± 0.80 |

| Year | Species | O3 Treatment | PII (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Populus maximowiczii Henry X P. × berolinensis Dippel | Ambient Air | 1.52 ± 0.74 |

| 1.5 | 5.79 ± 1.99 | ||

| 2.0 | 9.07 ± 1.96 | ||

| 2017 | Arbutus unedo | Ambient Air | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| 1.5 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ||

| 2.0 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | ||

| 2018 | Phillyrea angustifolia | Ambient Air | 0 |

| 1.5 | 0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0 | ||

| 2018 | Vaccinium myrtillus | Ambient Air | 1.76 ± 0.64 |

| 2.0 | 9.14 ± 0.35 | ||

| 2018 | Sorbus aucuparia | Ambient Air | 3.99 ± 0.71 |

| 2.0 | 11.27 ± 2.40 | ||

| 2018 | Alnus glutinosa | Ambient Air | 0.66 ± 0.51 |

| 2.0 | 7.04 ± 1.88 | ||

| 2019 | Pinus pinea | Ambient Air | 0 |

| 1.5 | 0 | ||

| 2.0 | 0 | ||

| 2020 | Populus maximowiczii Henry X P. × berolinensis Dippel | Ambient Air | 1.52 ± 0.79 |

| 1.5 | 6.29 ± 2.02 | ||

| 2.0 | 10.02 ± 2.11 | ||

| 2020 | Populus x euramericana I-214 | Ambient Air | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| 1.5 | 1.88 ± 0.72 | ||

| 2.0 | 4.02 ± 1.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manzini, J.; Hoshika, Y.; Moura, B.B.; Paoletti, E. Exploring a New O3 Index as a Proxy for the Avoidance/Tolerance Capacity of Forest Species to Tolerate O3 Injury. Forests 2023, 14, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14050901

Manzini J, Hoshika Y, Moura BB, Paoletti E. Exploring a New O3 Index as a Proxy for the Avoidance/Tolerance Capacity of Forest Species to Tolerate O3 Injury. Forests. 2023; 14(5):901. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14050901

Chicago/Turabian StyleManzini, Jacopo, Yasutomo Hoshika, Barbara Baesso Moura, and Elena Paoletti. 2023. "Exploring a New O3 Index as a Proxy for the Avoidance/Tolerance Capacity of Forest Species to Tolerate O3 Injury" Forests 14, no. 5: 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14050901