Economic Evaluation of Different Implementation Variants and Categories of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 Using Forestry in Germany as a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study: Germany

2.2. Simulation Model

- a forest-growth model that has been developed utilizing Sloboda functions derived from yield tables, which incorporates the silvicultural treatment technique of moderate thinning from below [30];

- a forest management model, with variable settings of different management parameters, such as harvesting type, rotation age, basal area, number of trees planted, and intended age structure;

- mean survival probabilities for each tree species, based on Weibull functions as the hazard rate and the survival probability models of Brandl et al. (2020) [31];

- an economic evaluation model which handles the financial–mathematical calculation of the economic key figures based on cost and revenue functions.

2.3. Model Developments and Advancements

2.3.1. Choice of the CWD Calculator

2.3.2. Implementation in the Model

2.4. Database

2.5. Scenarios

- (1)

- Strictly protected forests (SPF) that are set aside for natural processes protection and are unavailable for raw wood production;

- (2)

- Protected forests (PF), which include all legally protected area categories with nature protection as the priority function, on which (restricted) raw wood production is permitted;

- (3)

- Multifunctional forests with minimum standards of nature conservation (MF), which include all forest areas without the priority function of biodiversity protection, in which multifunctional forest management is applicable and raw wood production is possible in compliance with the generally valid, legal requirements of biodiversity protection.

- (1)

- The BAU Scenario represents the status quo of the German forest area and forest management practices and therefore serves as a reference to the MSC and ISC scenarios. It comprises a total of protected and strictly protected forests of 2.8 M ha, which includes Natura 2000, process protection, and other areas with a strong protection statuses [20,51]. The present SPF category comprises all forests where forest utilization is not allowed or not to be expected due to their off-site classification as nature conservation forest or protection forest [20]. In BAU, the SPF area therefore amounts in total to 178 K ha of set-aside forest. The PF area in this scenario is 882 K ha, comprising forest habitat types under the Habitats Directive of roughly 816 K ha [52], in addition to an assumed further lump sum of 66 K ha for species protection sites [8]. The remaining area of 1.74 M ha (2.8 M ha less SPF and Habitat area) is managed as filling and buffer zones. Furthermore, this scenario follows the statement of Sabatini et al. (2018 and 2020) that Germany features no old-growth forests [5,6].

- (2)

- In the Moderate Scenario (MSC), the initial status quo of total protected forest area also amounts to 2.8 M ha. Here, the PF area includes only designated European protected area categories (2.57 M ha, i.e., all Natura 2000 areas) and SPF areas include forests under natural development (227 K ha, National Strategy on Biological Diversity). With these potential settings, the EUBDS minimum target area share of protected forest area (SPF and PF) is not yet fulfilled. For the additional demand of protected area, it is assumed that all land use types must designate process conservation areas proportionally according to their share in the German land area. In this case, a further 1.03 M ha of forest area has to be set aside for the SPF area and a further 1.57 M ha of forests for the PF area [7]. Same as in BAU, no old-growth forests are designated in Germany in this scenario [5,6].

- (3)

- In the Intensive Scenario (ISC), Timm et al. (2022) and Schier et al. (2022) assume that, in addition to the European protected area categories, national protected area categories (e.g., nature reserves, nature parks, or landscape conservation areas) are also recognised as protected forest areas in the opening balance as status quo [7,19]. With a total of, in this case, 14.7 M ha of protected land area (of which 6.5 M ha are forests), the required protected area share of first EUBDS objective (“Legally protect a minimum of 30% of the EU’s land area…”) is therefore already exceeded in this scenario [53]. Consequently, the relative application of the second EUBDS target (“strictly protect at least a third of the EU’s protected areas…”) entails the designation of an extensive additional SPF area. Opposed to the MSC scenario, it is assumed here that only 500 K ha of non-forest land-use, mainly consisting of peatland restoration area, can be contributed to strictly protected land [54] and that all other areas (4.16 M ha) have to be supplied by forests [7,19]. In contrast to the moderate scenario (MSC), German “development old growth forests”, which are here all defined as old-growth forests above the usual rotation periods of the tree species groups [7,19], are included in the SPF category. Additionally, in this scenario, the nature conservation management requirements of all existing PF areas with a low protection status (e.g., nature parks or landscape conservation areas) are raised to Natura 2000 protection level and nature conservation measures are implemented accordingly.

2.6. Forest Economic Assessment

| BAU | MSC | ISC | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status Quo | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | ||

| Protected forest (PF) | ||||||||

| Total PF Area [1000 ha] | 2622 | 2573 | +1569 | 4142 | 6311 | −4164 | 2147 | [7,20,54] |

| of which habitat type with conservation measure | 882 | 882 | +819 | 1701 | 882 | +1265 | 2147 | [52,53] |

| Area deduction | all forests designated as forest habitat types under the Habitats Directive plus further areas for species protection | all forests designated as forest habitat types under the Habitats Directive plus further areas for species protection | proportion of existing tree species groups in habitat types transferred to expansion area, deduction over all age classes | sum of status quo and scenario changes | all forests designated as forest habitat types under the Habitats Directive plus further areas for species protection | area decrease for additional SPF area designation and habitat type requirements across the PF area | sum of status quo and scenario changes | [7,9,20] |

| Conservation measures | ||||||||

| (i) Tree species composition | min. 80% deciduous | min. 80% deciduous | no further change | min. 80% deciduous | min. 80% deciduous | no further change | min. 80% deciduous | [11,20] |

| (ii) Permanent habitat trees (age class 100 years and above; 100 m2 per habitat tree) | 2 trees per ha, | 2 trees/ha on already existing and 0.5 trees per ha on newly designated PF areas | +3 trees per ha on already existing and + 4.5 tree per ha on newly designated PF areas | 5 trees per ha | 2 trees per ha | +3 trees per ha | 5 trees per ha | [8] |

| (iii) CWD | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | beech: +35.78 m3 ha−1 oak: +39.40 m3 ha−1 spruce: +33.39 m3 ha−1 pine: +33.39 m3 ha−1 in 20 years | beech: 50 m3 ha−1 oak: 50 m3 ha−1 spruce: 50 m3 ha−1 pine: 50 m3 ha−1 | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | beech: +35.78 m3 ha−1 oak: +39.40 m3 ha−1 spruce: +33.39 m3 ha−1 pine: +33.39 m3 ha−1 in 20 years | beech: 50 m3 ha−1 oak: 50 m3 ha−1 spruce: 50 m3 ha−1 pine: 50 m3 ha−1 | [11,20,56] |

| (iv) Rotation period | 20 years above the average on MF areas | already existing PF areas: 20 years above average of MF areas | newly designated PF areas: +20 years | 20 years above average on existing and newly designated areas | 20 years above average of MF areas | no further change | 20 years above average of MF areas | [8,33] |

| of which filling and buffer zones | 1740 | 1691 | +750 | 2441 | 5429 | −5429 | 0 | |

| Area deduction | all forests designated as forest habitat types under the Habitats Directive plus further areas for species protection | European Natura 2000 protected area categories and all-natural forest development sites | proportion of existing tree species groups in habitat types transferred to expansion area, deduction over all age classes | sum of status quo and scenario changes | all protected area categories are treated as forest habitat types | area decrease for additional SPF area designation and habitat type requirements across the PF area | sum of status quo and scenario changes | [7,8,20] |

| Conservation measures | see multifunctional forests with minimum standards of nature conservation | |||||||

| BAU | MSC | ISC | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status Quo | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | ||

| Multifunctional forests with minimum standards of nature conservation (MF) | ||||||||

| MF Area [1000 ha] | 7828 | 7828 | −2600 | 5228 | 4156 | 0 | 4156 | |

| Area deduction | total accessible forest area less SPF and PF areas | total accessible forest area less SPF and PF areas | total accessible forest area less SPF and PF areas | own calculation | ||||

| Conservation measures | ||||||||

| (i) Tree species composition | status quo according to NFI 2012 | status quo according to NFI 2012 | change according to development between NFI 2002 and 2012 | change according to development between NFI 2002 and 2012 | status quo according to NFI 2012 | change according to development between NFI 2002 and 2012 | change according to development between NFI 2002 and 2012 | [8,20,29] |

| (ii) Permanent habitat trees (age class 100 yrs. and above; 100 m2 per habitat tree) | 0.5 trees per ha | 0.5 trees per ha | no further change | 0.5 trees per ha | 0.5 trees per ha | no further change | 0.5 trees per ha | |

| (iii) CWD | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | no further change | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | no further change | beech: 14.22 m3 ha−1 oak: 10.6 m3 ha−1 spruce: 16.61 m3 ha−1 pine: 16.61 m3 ha−1 | |

| (iv) Rotation period | averages per tree species group taken from WEHAM 2012 | averages per tree species group taken from WEHAM 2012 | no further change | averages per tree species group taken from WEHAM 2012 | averages per tree species group taken from WEHAM 2012 | no further change | averages per tree species group taken from WEHAM 2012 | |

| Sum of area [1000 ha] | 10,628 | 10,628 | 0 | 10,628 | 10,628 | 0 | 10,628 | |

3. Results

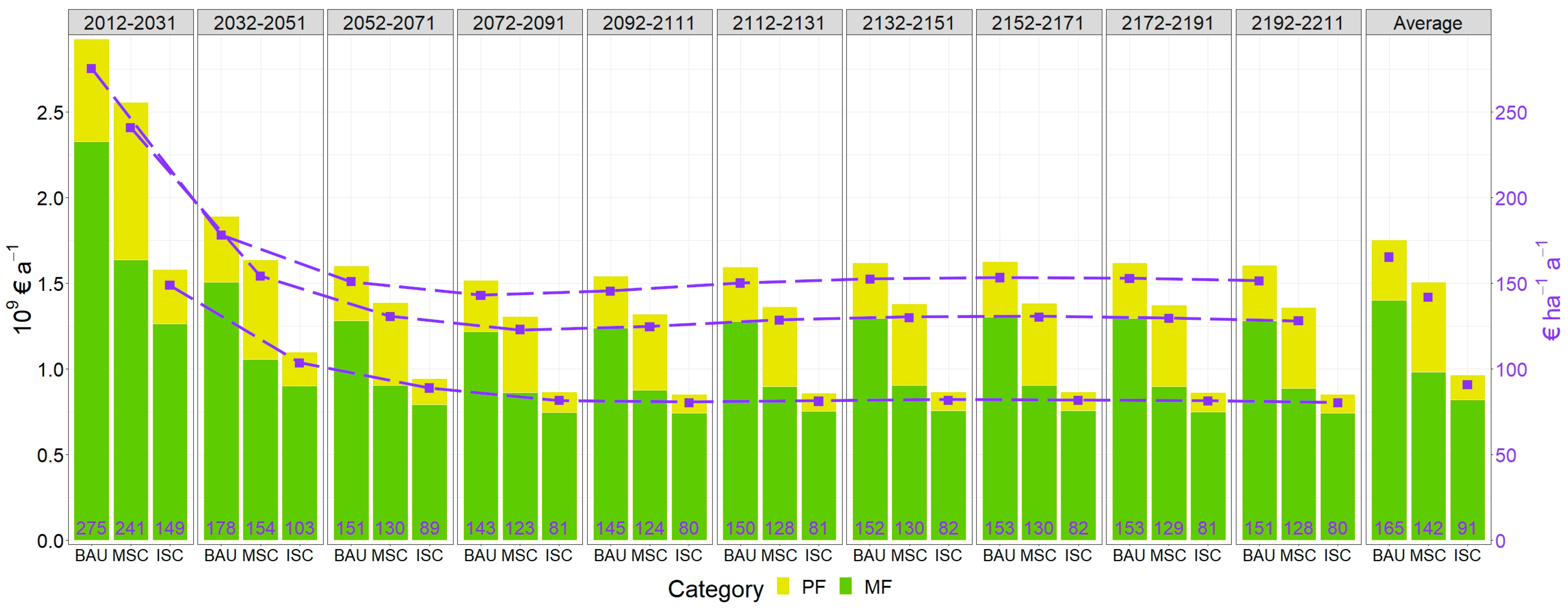

3.1. Total Fellings and Contribution Margin

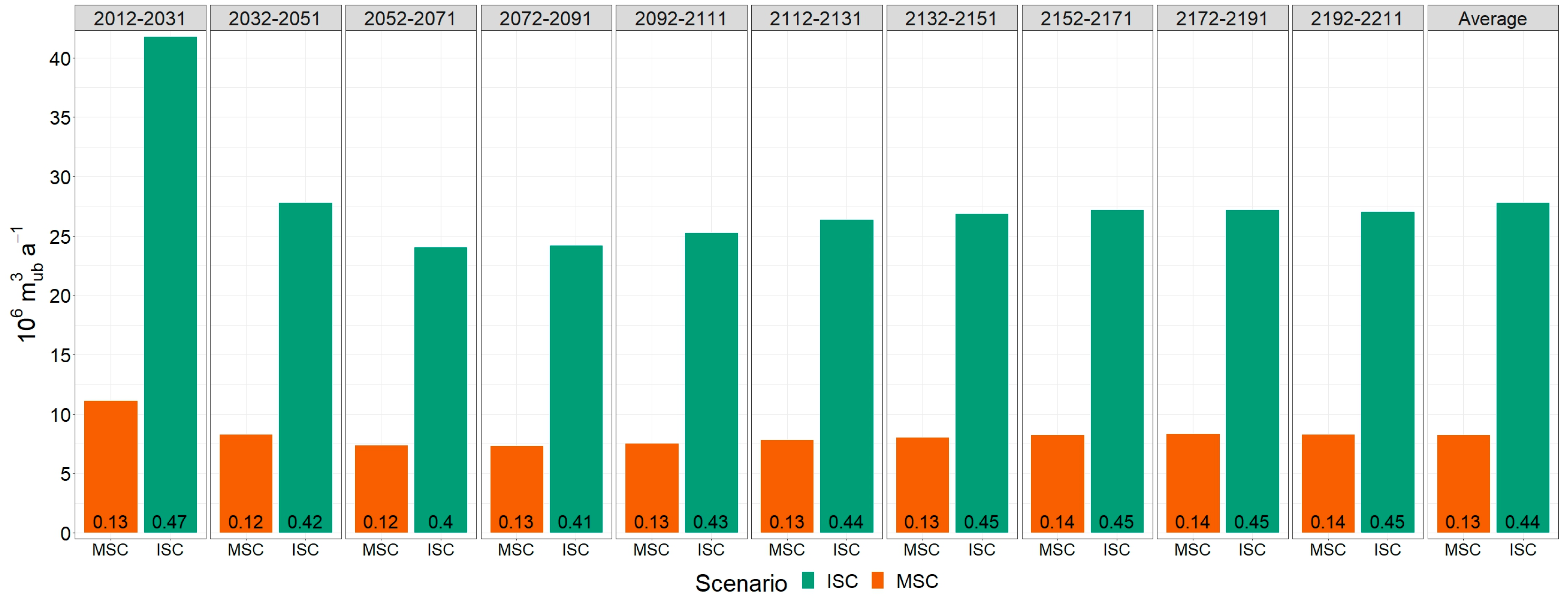

3.1.1. Total Fellings

3.1.2. Silvicultural Contribution Margin

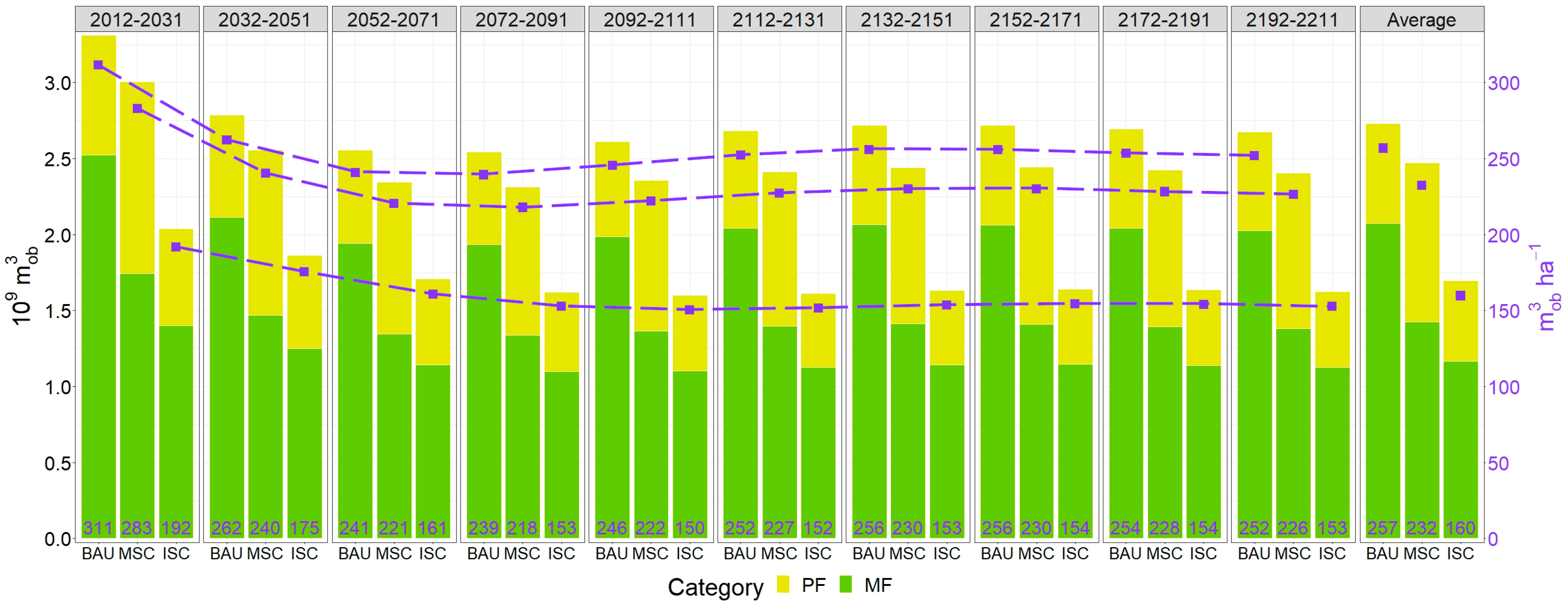

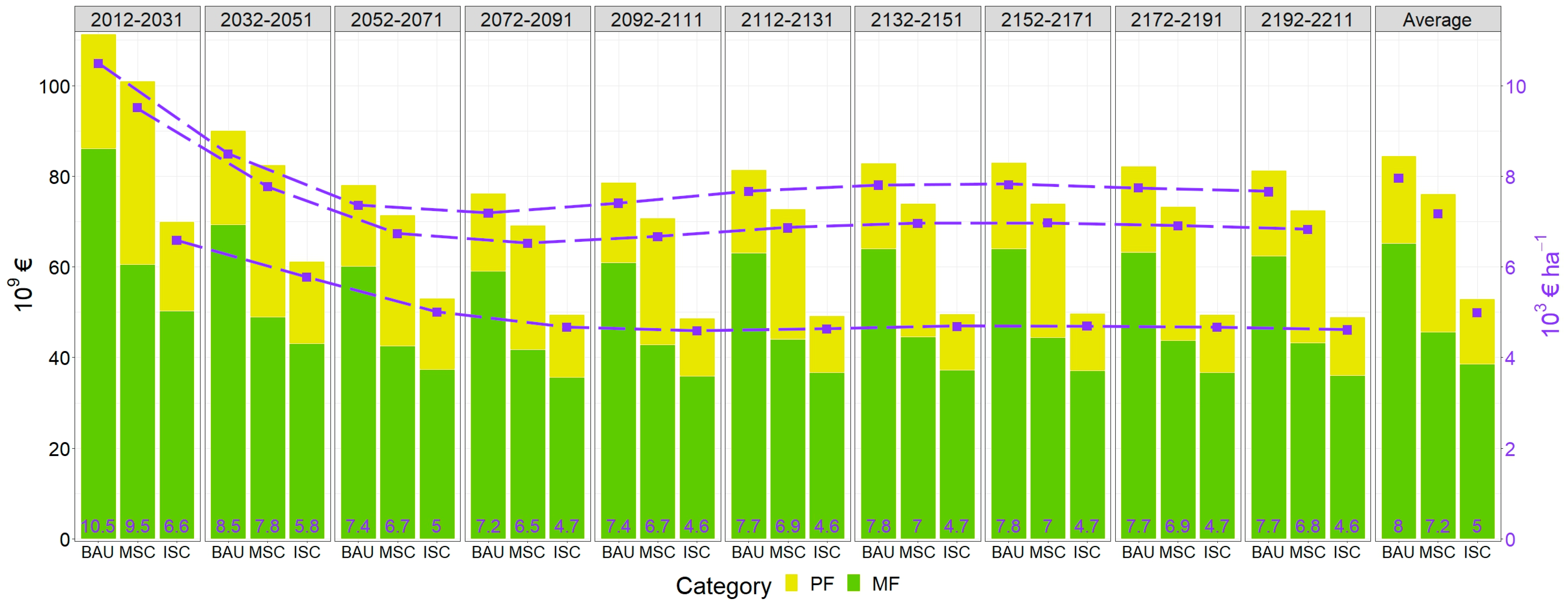

3.2. Timber Stock and Liquidation Value

3.2.1. Timber Stock

3.2.2. Liquidation Value

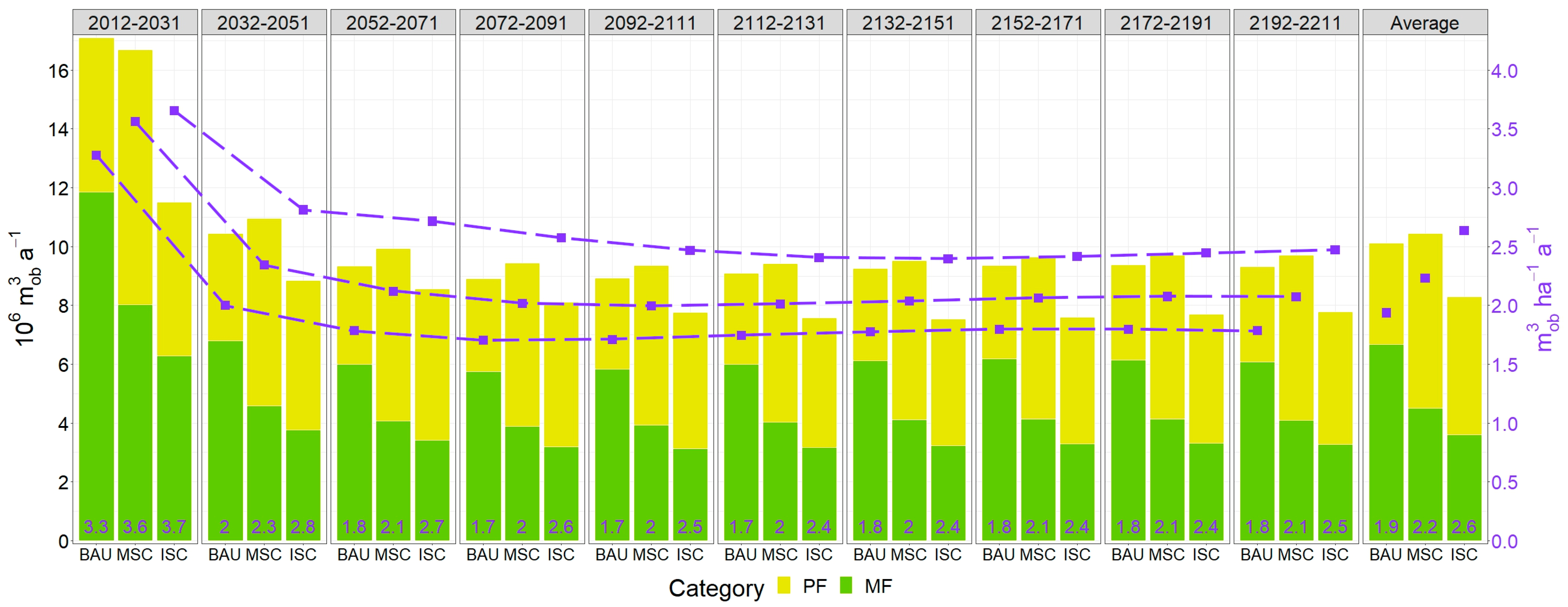

3.3. Supply and Development of Coarse Woody Debris

3.3.1. Supply of Coarse Woody Debris

3.3.2. Economic Evaluation of Coarse Woody Debris

3.4. Opportunity Costs of MSC und ISC

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Methods

4.1.1. Constraints and Limitations of the Model

4.1.2. CWD Calculator

4.1.3. Scenarios

4.2. Discussion of Results

4.2.1. Natural Results

4.2.2. Economic Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of the Results

5.2. Outlook and Research Desiderata

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Plots

Appendix B. Tables

| Growing Stock ob [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 786,479 | 670,392 | 614,960 | 608,396 | 622,441 | 640,220 | 651,623 | 654,594 | 651,452 | 647,144 | 654,770 |

| MF | 2,523,706 | 2,115,370 | 1,941,847 | 1,934,424 | 1,987,860 | 2,041,609 | 2,066,163 | 2,062,795 | 2,043,188 | 2,027,707 | 2,074,467 |

| Total | 3,310,185 | 2,785,763 | 2,556,807 | 2,542,820 | 2,610,301 | 2,681,829 | 2,717,786 | 2,717,389 | 2,694,640 | 2,674,851 | 2,729,237 |

| Total fellings ub [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 19,020 | 14,459 | 12,967 | 12,603 | 12,694 | 12,923 | 13,069 | 13,105 | 13,063 | 12,978 | 13,688 |

| MF | 69,933 | 52,117 | 47,119 | 45,914 | 46,127 | 46,815 | 47,148 | 47,353 | 47,194 | 46,852 | 49,657 |

| Total | 88,954 | 66,576 | 60,087 | 58,517 | 58,822 | 59,738 | 60,217 | 60,457 | 60,257 | 59,829 | 63,345 |

| Total CWD [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 55,862 | 64,226 | 67,593 | 69,424 | 70,378 | 70,608 | 70,376 | 69,885 | 69,171 | 68,399 | 67,592 |

| MF | 132,331 | 138,118 | 140,687 | 141,295 | 140,318 | 138,519 | 135,920 | 133,238 | 130,348 | 127,756 | 135,853 |

| Total | 188,193 | 202,344 | 208,279 | 210,720 | 210,696 | 209,127 | 206,295 | 203,123 | 199,519 | 196,155 | 203,445 |

| Outflow of unutilized timber [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 5248 | 3661 | 3326 | 3149 | 3095 | 3095 | 3136 | 3192 | 3231 | 3234 | 3437 |

| MF | 11,854 | 6789 | 6002 | 5750 | 5834 | 6004 | 6130 | 6174 | 6138 | 6079 | 6675 |

| Total | 17,101 | 10,450 | 9328 | 8899 | 8929 | 9098 | 9266 | 9366 | 9369 | 9314 | 10,112 |

| Silvicultural contribution margin [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 598,221 | 385,679 | 321,278 | 298,508 | 303,343 | 315,791 | 323,710 | 326,793 | 326,789 | 324,645 | 352,476 |

| MF | 2,328,294 | 1,506,284 | 1,282,414 | 1,218,974 | 1,238,788 | 1,278,187 | 1,294,902 | 1,301,340 | 1,294,389 | 1,282,435 | 1,402,601 |

| Total | 2,926,515 | 1,891,963 | 1,603,691 | 1,517,482 | 1,542,131 | 1,593,979 | 1,618,612 | 1,628,134 | 1,621,178 | 1,607,080 | 1,755,076 |

| Liquidation value [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 25,306,578 | 20,761,455 | 17,925,798 | 17,233,069 | 17,654,021 | 18,345,160 | 18,846,568 | 19,052,115 | 19,002,235 | 18,851,434 | 19,297,843 |

| MF | 86,099,494 | 69,401,900 | 60,211,039 | 59,026,933 | 60,982,949 | 63,051,216 | 64,025,184 | 63,952,030 | 63,200,358 | 62,470,957 | 65,242,206 |

| Total | 111,406,072 | 90,163,355 | 78,136,837 | 76,260,002 | 78,636,970 | 81,396,376 | 82,871,751 | 83,004,145 | 82,202,593 | 81,322,391 | 84,540,049 |

| Growing Stock ob [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 1,262,221 | 1,086,122 | 995,790 | 977,665 | 991,839 | 1,013,682 | 1,028,556 | 1,033,393 | 1,029,139 | 1,022,174 | 1,044,058 |

| MF | 1,744,817 | 1,467,921 | 1,348,172 | 1,336,923 | 1,367,069 | 1,399,231 | 1,413,551 | 1,409,856 | 1,395,513 | 1,383,355 | 1,426,641 |

| Total | 3,007,039 | 2,554,043 | 2,343,962 | 2,314,587 | 2,358,908 | 2,412,913 | 2,442,107 | 2,443,250 | 2,424,652 | 2,405,529 | 2,470,699 |

| Total fellings ub [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 29,663 | 22,447 | 20,087 | 19,431 | 19,496 | 19,777 | 19,880 | 19,858 | 19,733 | 19,565 | 20,994 |

| MF | 48,136 | 35,837 | 32,609 | 31,748 | 31,774 | 32,114 | 32,259 | 32,329 | 32,188 | 31,935 | 34,093 |

| Total | 77,799 | 58,284 | 52,696 | 51,178 | 51,270 | 51,890 | 52,139 | 52,186 | 51,921 | 51,500 | 55,086 |

| Total CWD [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 91,451 | 106,441 | 113,430 | 117,761 | 120,376 | 121,672 | 121,977 | 121,757 | 120,978 | 120,037 | 115,588 |

| MF | 89,929 | 93,799 | 95,571 | 96,038 | 95,441 | 94,281 | 92,572 | 90,785 | 88,859 | 87,105 | 92,438 |

| Total | 181,380 | 200,239 | 209,001 | 213,799 | 215,817 | 215,953 | 214,549 | 212,541 | 209,837 | 207,142 | 208,026 |

| Outflow of unutilized timber [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 8663 | 6374 | 5859 | 5549 | 5426 | 5389 | 5421 | 5504 | 5586 | 5617 | 5939 |

| MF | 8026 | 4592 | 4067 | 3886 | 3923 | 4026 | 4109 | 4144 | 4126 | 4090 | 4499 |

| Total | 16,689 | 10,966 | 9926 | 9435 | 9349 | 9415 | 9530 | 9648 | 9712 | 9706 | 10,438 |

| Silvicultural contribution margin [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 922,035 | 582,797 | 481,087 | 442,279 | 446,949 | 465,191 | 475,808 | 479,386 | 477,475 | 473,100 | 524,611 |

| MF | 1,635,781 | 1,055,920 | 904,513 | 863,380 | 874,890 | 897,486 | 904,355 | 904,491 | 897,270 | 887,601 | 982,569 |

| Total | 2,557,816 | 1,638,717 | 1,385,600 | 1,305,660 | 1,321,839 | 1,362,677 | 1,380,163 | 1,383,877 | 1,374,746 | 1,360,702 | 1,507,180 |

| Liquidation value [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 40,482,730 | 33,529,666 | 28,915,573 | 27,529,186 | 27,881,470 | 28,727,232 | 29,372,543 | 29,651,460 | 29,568,510 | 29,324,740 | 30,498,311 |

| MF | 60,588,285 | 48,946,785 | 42,578,481 | 41,734,672 | 42,910,168 | 44,103,172 | 44,576,767 | 44,390,206 | 43,789,812 | 43,216,797 | 45,683,515 |

| Total | 101,071,015 | 82,476,451 | 71,494,055 | 69,263,859 | 70,791,638 | 72,830,404 | 73,949,310 | 74,041,666 | 73,358,322 | 72,541,537 | 76,181,826 |

| Growing Stock ob [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 635,758 | 613,015 | 566,259 | 522,325 | 494,036 | 483,977 | 486,876 | 494,331 | 499,346 | 498,294 | 529,422 |

| MF | 1,401,565 | 1,249,802 | 1,141,784 | 1,100,215 | 1,105,390 | 1,127,829 | 1,144,442 | 1,146,842 | 1,137,851 | 1,126,199 | 1,168,192 |

| Total | 2,037,323 | 1,862,817 | 1,708,043 | 1,622,540 | 1,599,426 | 1,611,806 | 1,631,318 | 1,641,174 | 1,637,197 | 1,624,493 | 1,697,614 |

| Total fellings ub [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 11,329 | 9420 | 8560 | 7901 | 7528 | 7306 | 7192 | 7091 | 6974 | 6853 | 8015 |

| MF | 35,811 | 29,310 | 27,464 | 26,407 | 26,007 | 26,004 | 26,093 | 26,146 | 26,089 | 25,929 | 27,526 |

| Total | 47,140 | 38,730 | 36,024 | 34,307 | 33,535 | 33,310 | 33,286 | 33,237 | 33,062 | 32,782 | 35,541 |

| Total CWD [1000 m3] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 53,033 | 65,387 | 74,130 | 81,598 | 87,282 | 92,137 | 95,551 | 98,463 | 100,214 | 101,642 | 84,944 |

| MF | 71,054 | 73,613 | 75,286 | 76,316 | 76,687 | 76,596 | 75,996 | 75,157 | 74,063 | 72,898 | 74,767 |

| Total | 124,086 | 139,000 | 149,416 | 157,913 | 163,968 | 168,733 | 171,547 | 173,620 | 174,277 | 174,540 | 159,710 |

| Outflow of unutilized timber [1000 m3 a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 5226 | 5086 | 5125 | 4912 | 4640 | 4412 | 4299 | 4310 | 4401 | 4500 | 4691 |

| MF | 6280 | 3771 | 3427 | 3193 | 3122 | 3165 | 3241 | 3295 | 3307 | 3284 | 3608 |

| Total | 11,507 | 8856 | 8551 | 8105 | 7762 | 7576 | 7540 | 7605 | 7707 | 7785 | 8299 |

| Silvicultural contribution margin [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 317,212 | 197,778 | 151,262 | 120,112 | 109,551 | 108,092 | 110,028 | 111,766 | 111,690 | 109,261 | 144,675 |

| MF | 1,262,410 | 900,478 | 791,122 | 744,989 | 740,955 | 751,863 | 756,618 | 754,982 | 749,007 | 741,025 | 819,345 |

| Total | 1,579,621 | 1,098,256 | 942,385 | 865,100 | 850,506 | 859,955 | 866,646 | 866,748 | 860,698 | 850,286 | 964,020 |

| Liquidation value [1000 EUR a−1] | 2012–2031 | 2032–2051 | 2952–2071 | 2072–2091 | 2092–2111 | 2112–2131 | 2132–2151 | 2152–2171 | 2172–2191 | 2192–2211 | Average |

| PF | 19,637,920 | 18,176,834 | 15,752,977 | 13,876,581 | 12,817,770 | 12,436,113 | 12,458,344 | 12,681,086 | 12,853,709 | 12,825,281 | 14,351,662 |

| MF | 50,300,654 | 43,107,954 | 37,400,136 | 35,641,581 | 35,937,995 | 36,745,175 | 37,205,299 | 37,138,624 | 36,671,318 | 36,114,620 | 38,626,336 |

| Total | 69,938,574 | 61,284,788 | 53,153,113 | 49,518,163 | 48,755,765 | 49,181,288 | 49,663,643 | 49,819,709 | 49,525,027 | 48,939,901 | 52,977,997 |

References

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Eurostat. EU Area Covered by Forests in 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20210321-1 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Barredo, J.I.; Brailescu, C.; Teller, A.; Sabatini, F.M.; Mauri, A.; Janouskova, K. Mapping and Assessment of Primary and Old-Growth Forests in Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Sabatini, F.M.; Burrascano, S.; Keeton, W.S.; Levers, C.; Lindner, M.; Pötzschner, F.; Verkerk, P.J.; Bauhus, J.; Buchwald, E.; Chaskovsky, O.; et al. Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Divers Distrib. 2018, 24, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F.M.; Bluhm, H.; Kun, Z.; Aksenov, D.; Atauri, J.A.; Buchwald, E.; Burrascano, S.; Cateau, E.; Diku, A.; Duarte, I.M.; et al. European Primary Forest Database (EPFD) v2.0. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, F.; Iost, S.; Seintsch, B.; Weimar, H.; Dieter, M. Assessment of Possible Production Leakage from Implementing the EU Biodiversity Strategy on Forest Product Markets. Forests 2022, 13, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, L.; Seintsch, B. Opportunitätskostenanalyse zur Implementierung des naturschutzorientierten Waldbehandlungskonzepts “Neue Multifunktionalität”. Landbauforsch Appl. Agric. For. Res. 2015, 3/4, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, M.E.; Franklin, J.F.; Swanson, F.J.; Sollins, P.; Gregory, S.V.; Lattin, J.D.; Anderson, N.H.; Cline, S.P.; Aumen, N.G.; Sedell, J.R.; et al. Ecology of Coarse Woody Debris in Temperate Ecosystems. In Advances in Ecological Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 133–302. ISBN 0065-2504. [Google Scholar]

- Kroiher, F.; Oehmichen, K. Das Potenzial der Totholzakkumulation im deutschen Wald | Potential of deadwood accumulation in German forests. Schweiz. Z. Fur Forstwes. 2010, 161, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssymank, A.; Hauke, U.; Rückriem, C.; Schröder, E. Das Europäische Schutzgebietssystem Natura 2000: BfNHandbuch zur Umsetzung der Fauna-Flora-Habitat-Richtlinie und der Vogelschutz-Richtlinie; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kniivilä, M.; Saastamoinen, O. The opportunity costs of forest conservation in a local economy. Silva Fenn. 2002, 36, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, H.; Mayer, M. Forstwirtschaft versus Waldnaturschutz: Regionalwirtschaftliche Opportunitätskosten des Nationalparks Bayerischer Wald. Allg. Forst- U. J.-Ztg. 2012, 183, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz, L.; Seintsch, B.; Wippel, B.; Dieter, M. Income losses due to the implementation of the Habitats Directive in forests —Conclusions from a case study in Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 38, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A.; Młynarski, W. Opportunity costs of establishing nature reserves in selected forest districts of the Mazowieckie Province. For. Res. Pap. 2014, 75, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dög, M.; Seintsch, B.; Rosenkranz, L.; Dieter, M. Belastungen der deutschen Forstwirtschaft aus der Schutz- und Erholungsfunktion des Waldes. Landbauforschung 2016, 66, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buongiorno, J. The Global Forest Products Model: Structure, Estimation, and Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 9780121413620. [Google Scholar]

- Dieter, M.; Weimar, H.; Iost, S.; Englert, H.; Fischer, R.; Günter, S.; Morland, C.; Roering, H.-W.; Schier, F.; Seintsch, B.; et al. Assessment of possible leakage effects of implementing EU COM proposals for the EU Biodiversity Strategy on forests and forest management in non-EU countries. Thünen Work. Pap. 2020, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, S.; Dieter, M.; Fischer, R.; Günter, S.; Heinrich, B.; Iost, S.; Matthes, U.; Rock, J.; Rüter, S.; Schabel, A.; et al. Konsequenzen der “EU-Biodiversitätsstrategie 2030” für Wald und Forstwirtschaft in Deutschland: Abschlussbericht. LWF Mater. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar]

- NFI. Dritte Bundeswaldinventur Ergebnisdatenbank: German National Forest Inventory. Waldfläche (Gemäß Standflächenanteil) [ha] nach Baumartengruppe und Baumaltersklasse, Filter: Jahr=2012. Available online: https://bwi.info (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Schluhe, M.; Englert, H.; Wördehoff, R.; Schulz, C.; Dieter, M.; Möhring, B. Klimarechner zur Quantifizierung der Klimaschutzleistung von Forstbetrieben auf Grundlage von Forsteinrichtungsdaten. Landbauforsch Appl. Agric. For. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kareiva, P.; Tallis, H.; Ricketts, T.H.; Daily, G.C.; Polasky, S. Natural Capital: Theory and Practice of Mapping Ecosystem Services; Oxford University Press, Incorporated: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780191621031. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, K.J.; Holmes, T.P. Choice experiments and valuing forest attributes. In Handbook of Forest Resource Economics; Earthscan from Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 151–164. ISBN 9780203105290. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, M.; Loomis, J.; DeLacy, T. A Contingent Valuation Survey and Benefit-Cost Analysis of Forest Preservation in East Gippsland, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 1993, 38, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FADN. Accounting Results of the German Forestry Industry: Forest Accountancy Data Network. 2022. Unpublished. Available online: https://www.bmel-statistik.de/landwirtschaft/testbetriebsnetz/testbetriebsnetz-forst-buchfuehrungsergebnisse/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Eurostat. Roundwood Production in the EU-27.tag00072. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tag00072/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- FRA. Global Forest Resources Assessment: Overview EU-27. Available online: https://fra-data.fao.org/EU27/fra2020/home (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Oesten, G.; Roeder, A. Management von Forstbetrieben; Kessel: Remagen, Germany, 2002; ISBN 3935638167. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz, L.; Selzer, A.M.; Seintsch, B. Verbundforschungsbericht WEHAM-Szenarien: Stakeholderbeteiligung bei der Entwicklung und Bewertung von Waldbehandlungs- und Holzverwendungsszenarien; Thünen-Institut, Bundesforschungsinstitut für Ländliche Räume, Wald und Fischerei: Braunschweig, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda, B. Zur Darstellung von Wachstumsprozessen mit Hilfe von Differentialgleichungen Erster Ordnung; Mitt. d. Baden-Württembergischen Forstlichen Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt: Freiburg, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Brandl, S.; Paul, C.; Knoke, T.; Falk, W. The influence of climate and management on survival probability for Germany’s most important tree species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, R. Ertragstafeln Wichtiger Baumarten bei Verschiedener Durchforstung; JD Sauerländer Verlag: Bad Orb, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M.; Vesterdal, L. Hysical and chemical properties of decaying beech wood in two Danish forest reserves. Nat.-Man Work. Rep. 2003, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, P.; Menke, N.; Nagel, J.; Hansen, J.; Kawaletz, H.; Paar, U.; Evers, J. Entwicklung eines Managementmoduls für Totholz im Forstbetrieb; NW-FVA: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mues, V.; Knauf, M.; Köhl, M.; Frühwald, A. Bewertung der Klimaschutzleistungen der Forst- und Holzwirtschaft auf Lokaler Ebene (BEKLIFUH): Ein Projekt im Rahmen des Waldklimafonds. Dokumentation, Stand 1. August 2018; NRW: Hamburg/Bielefeld, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, J.; Badeck, F.-W.; Harmon, M.E. Estimating decomposition rate constants for European tree species from literature sources. Eur. J. For. Res. 2008, 127, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, C. Totholzanfall in Einem Buchenaltbestand im Nationalpark Hainich/Thüringen; Dipl.arb. Albert-Ludwig-Univ.: Freiburg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, T. Abbauraten von Fichtentotholz (Picea abies) Bohrwiderstandsmessungen als Neuer Ansatz zur Bestimmung des Totholzabbaus, Einer Wichtigen Größe im Kohlenstoffhaushalt Mitteleuropäischer Wälder; NW-FVA: Jena, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, T. Kohlenstofftransport aus dem Totholz in den Boden; Diss. Univ. Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Using, S. Totholzdynamik eines Buchenbestandes im Solling; Ber. Forschungszentrum Waldökosysteme: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; N. G. G. I. Programme, Eggleston, H.S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IGES: Kyoto, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UBA. Berichterstattung unter der Klimarahmenkonvention der Vereinten Nationen und dem Kyoto-Protokoll 2022: Nationaler Inventarbericht zum Deutschen Treibhausgasinventar 1990–2020; UBA: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Möhring, B.; Bitter, A.; Bub, G.; Dieter, M.; Dög, M.; Hanewinkel, M.; Graf von Hatzfeldt, N.; Köhler, J.; Ontrup, G.; Rosenberger, R.; et al. Schadenssumme insgesamt 12,7 Mrd. Euro: Abschätzung der ökonomischen Schäden der Extremwetterereignisse der Jahre 2018 bis 2020 in der Forstwirtschaft. Holz-Zent. 2021, 9, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz, L.; von Arnim, G.; Englert, H.; Husmann, K.; Regelmann, C.; Roering, H.-W.; Rosenberger, R.; Seintsch, B.; Dieter, M.; Möhring, B. Economic Evaluations of Alternative Forest Management Strategies to Adapt to Climate Change: A German Case Study; Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2023; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- MULE. Waldbewertungsrichtlinie des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt; Landeszentrum Wald: Magdeburg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://landeszentrumwald.sachsen-anhalt.de/fileadmin/Bibliothek/Politik_und_Verwaltung/MLU/Landeszentrum_Wald/LZW-PDF/Anlage_10_-_Kulturkostenstufen_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Hessen-Forst. Standardkulturkosten für die Waldbewertung der Servicestelle Waldbewertung Hessen-Forst, Stand 2019; DFWR: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- MELV. Waldbewertungsrichtlinien 2014 Niedersächsische Landesforsten. 2015. Available online: https://www.landesforsten.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/tab_13_kulturkosten_d7-15.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming; IPCC: Kyoto, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D.; von Storch, H. “Prediction” or “Projection”? Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F. Climate Change Prediction. Clim. Change 2005, 73, 239–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, F.; Bauhus, J.; Gärtner, S.; Kühn, A.; Meyer, P.; Reif, A.; Schmidt, M.; Schultze, J.; Späth, V.; Stübner, S.; et al. Wälder mit natürlicher Entwicklung in Deutschland: Bilanzierung und Bewertung, Naturschutz und Biologische Vielfalt; AFZ-DerWald: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BfN. Waldlebensraumtypen in Deutschland: Sonderauswertung des BfN im Auftrag des Verbundforschungsprojektes FFH-Impact; BFN: Bonn, Germany, 2012; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Röder, N.; Laggner, B. Landnutzung in Deutschland Nach Rechtlichem Schutzstatus der Flächen; Umweltbundesamt: Braunschweig, Germany, 2020; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, N.; Osterburg, B. The impact of map and data resolution on the determination of the agricultural utilization of organic soils in Germany. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, P.-O.; Löfgren, K.-G. The Economics of Forestry and Natural Resources; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985; ISBN 0631141626. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Terms and Definitions: Forest Resource Assessment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.; Nagel, J.; Schmidt, M.; Nagel, R.-V.; Spellmann, H. Eine neue Generation von Ertragstafeln für Eiche, Buche, Fichte, Douglasie und Kiefer; NW-FVA: Göttingen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Wade, C.M.; Baker, J.S.; Jones, J.P.; Latta, G.S.; Ohrel, S.B.; Ragnauth, S.A.; Creason, J.R. Implications of Alternative Land Conversion Cost Specifications on Projected Afforestation Potential in the United States. Methods Rep. RTI Press 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Golub, A.; Hertel, T.; Lee, H.-L.; Rose, S.; Sohngen, B. The opportunity cost of land use and the global potential for greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture and forestry. Resour. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietz, A.; Neumann, R.; Volkenand, S. Untersuchung der Eigentumsstrukturen von Landwirtschaftsfläche in Deutschland; Thünen Report No. 85; Thünen-Institut: Braunschweig, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Destatis. Nachhaltige Entwicklung in Deutschland: Indikatorenbericht 2022; Statistisches Bundesamt: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EFA. European Forest Account: Reporting Period 2014–2020. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Umwelt/UGR/landwirtschaft-wald/Publikationen/Downloads/waldgesamtrechnung-tabellenband-pdf-5852102.html (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Ermisch, N.; Seintsch, B.; Englert, H. Anteil des Holzertrages am Gesamtertrag der TBN-Betriebe. AFZ Der. Wald 2015, 70, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch, N.; Franz, K.; Seintsch, B.; Englert, H.; Dieter, M. Bedeutung der Fördermittel für den Ertrag der TBN-Forstbetriebe. AFZ Der. Wald 2016, 71, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

| Tree Species | Representative For | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Spruce | All spruce and fir species (Picea spec and Abies spec.), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and all other fast-growing, neophyte coniferous species | [32] |

| Pine | All pine and larch species (Pinus spec. and Larix spec.) | [32] |

| Beech | Beech and all deciduous tree species of high longevity except oak (e.g., maple (Acer spec.), lime (Tilia spec.), ash (Fraxinus spec.), and others) and low longevity (e.g., birch (Betula spec.), aspen (Populus tremula), willow (Salix spec.), or rowan (Sorbus aucuparia)) | [32] |

| Oak | All oak species (Quercus spec.) | [32] |

| Input Data | Unit | Spruce | Pine | Beech | Oak | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial values of CWD (without rootstocks and residues) | m3 ha−1 | 16.61 | 16.61 | 14.22 | 10.60 | [20] |

| k-Factor for CWD decay | Factor | 0.0525 | 0.0575 | 0.0670 | 0.0372 | [36] |

| Economic Input Data | Unit | Spruce | Pine | Beech | Oak | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs of regeneration for same tree species after regular felling | EUR ha−1 | 1300 | 1900 | 1800 | 2600 | [44,45,46] |

| Costs of regeneration for changing tree species after regular felling | EUR ha−1 | 4300 | 5800 | 10,200 | 16,500 | |

| Costs of regeneration after calamity in | EUR ha−1 | 5100 | 7500 | 12,400 | 18,900 | |

| Pre-commercial thinning costs | EUR ha−1 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | |

| Average felling costs (BAU) | EUR m−3 | 24.7 | 24.7 | 24.7 | 24.7 | [25] |

| Average timber prices | EUR m−3 | 78.4 | 62.6 | 58 | 95 | |

| Calamity-induced shortfalls in revenue | % | −4 | −20 | −20 | −10 | [43] |

| Calamity-induced additional expenses | % | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Factor of tree species survival after 100 years: | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.44 | [31,44,48] |

| BAU | MSC | ISC | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status Quo | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | Status Quo | Scenario Changes | Objective | ||

| Total protected forests (SPF and PF) | ||||||||

| Area [1000 ha] | 2800 | 2800 | +2600 | 5400 | 6471 | 0 | 6471 | [7,19,20,51,53] |

| Strictly protected forests (SPF) | ||||||||

| Total SPF Area [1000 ha] | 178 | 227 | +1031 | 1258 | 161 | +4164 | 4325 | [7,19,20,51,53] |

| of which process protection area | 178 | 227 | +1031 | 1258 | 161 | +3100 | 3261 | |

| Area deduction | all forests with the NFI-status “forest utilization not allowed or not to be expected” due to their off-site classification as nature conservation or protection forest | all-natural forest protection development sites according to the definition of Engel et al., 2016 | additional 1031 ha taken from MF areas; proportionate designation across all of all age groups and tree species | sum of status quo and scenario changes | core zones of national parks and biosphere reserves, according to Röder and Laggner 2020 | additional 3261 ha taken from PF areas; proportionate designation across all of all age groups and tree species | sum of status quo and scenario changes | |

| Conservation measures | SPF areas are defined as process protection areas without additional preservation measures | |||||||

| of which primary and old growth forest area | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1064 | 1064 | [5,6,7,19,20,53] |

| Area deduction | do not exist in Germany | do not exist in Germany | --- | designation of “development old growth forests” of all age classes above the regular rotation period: oak > 160 years, beech > 120 years, spruce > 120 years and pine > 140 years | sum of status quo and scenario changes | |||

| Conservation measures | SPF areas are defined as process protection areas without additional preservation measures | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Regelmann, C.; Rosenkranz, L.; Seintsch, B.; Dieter, M. Economic Evaluation of Different Implementation Variants and Categories of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 Using Forestry in Germany as a Case Study. Forests 2023, 14, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061173

Regelmann C, Rosenkranz L, Seintsch B, Dieter M. Economic Evaluation of Different Implementation Variants and Categories of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 Using Forestry in Germany as a Case Study. Forests. 2023; 14(6):1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061173

Chicago/Turabian StyleRegelmann, Cornelius, Lydia Rosenkranz, Björn Seintsch, and Matthias Dieter. 2023. "Economic Evaluation of Different Implementation Variants and Categories of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 Using Forestry in Germany as a Case Study" Forests 14, no. 6: 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061173

APA StyleRegelmann, C., Rosenkranz, L., Seintsch, B., & Dieter, M. (2023). Economic Evaluation of Different Implementation Variants and Categories of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 Using Forestry in Germany as a Case Study. Forests, 14(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061173