The Rationale for Restoration of Abandoned Quarries in Forests of the Ślęża Massif (Poland) in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Forest Environment Protection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope, Materials, and Methods

3. Study Area

3.1. Location and Its Tourist Implications

3.2. Topography and Geology

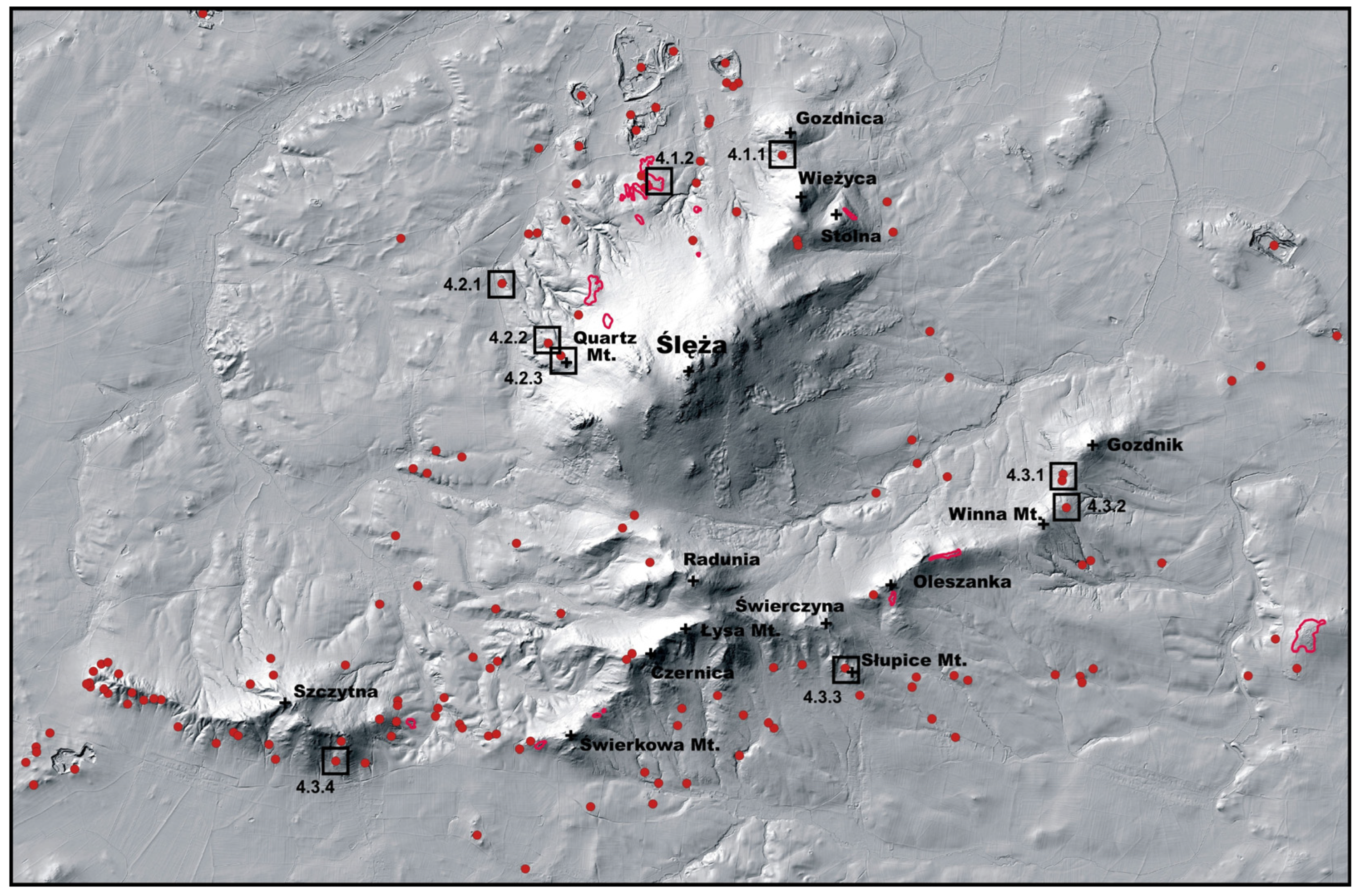

- The northern part extends from the town of Sobótka to the Tąpadła Pass; it comprises the most northerly summits of the area: Gozdnica (317.6 m.a.s.l.), Wieżyca (414.2 m.a.s.l.), and Stolna (368.4 m.a.s.l.), along with the centrally located Ślęża (718 m.a.s.l.), composed of Paleozoic igneous rocks, which are primarily granites as well as gabbros and amphibolites; granites in this part of the massif are transected by two massive quartz veins, extending in the NW-SE direction [42];

- The southern part, behind the Tąpadła Pass, is composed mainly of Devonian serpentinites and peridotites, with scarce amphibolites and aplites [43], morphologically constituting, as it were, a separate series of lower hills, which may be further distinguished: a segment with the peaks of Radunia (the Radunia Group Hills) (577.6 m.a.s.l.) and Czernica (487 m.a.s.l.), ranking second and third in the Ślęża Massif in terms of altitude, respectively, while the SE part of the massif contains a narrower belt of the Oleszna Hills with its highest hill Oleszenka (388 m.a.s.l.). The serpentinite belt in the westerly direction extends into the Kiełczyn Hills with the highest peak of Szczytna (466 m.a.s.l.).

3.3. History of Mining Activity in the Ślęża Region

3.4. Stands in the Ślęża Massif

4. Research Results—Characteristics of Selected Workings

4.1. Granite Quarries

4.1.1. “Prehistoric” Quarry

4.1.2. Small Quarries in Sobótka-Górka

4.2. Quartz Quarries

4.2.1. “White Cows” Quarry

4.2.2. Quartz Quarry near Sady Village

4.2.3. Quarry on the Quartz Mountain

4.3. Quarries of the Serpentinite Zone

4.3.1. Quarry in Przemiłów

4.3.2. Quarry on Winna Góra

4.3.3. The Słupice Mountain Quarry

4.3.4. The Quarry in Kiełczyn

4.4. Summary of Qualities Beneficial for Tourism

5. Discussion

- Respecting the natural and man-made geological outcrops by abstaining from filling the open-pit workings or collecting rock and mineral samples directly from the rock faces, except for samples collected for scientific purposes;

- Exposing geological value by the removal of shrubs and young trees, mainly self-seeded, if it is consistent with the interests of the protection of animate nature; if necessary, it includes clearing with the removal of biomass;

- The removal of branches after felling from the area adjacent to rocks and quarries, since it leads to the disappearance of thermophilic and rupestral vegetation;

- The gradual limitation of the share of geographically and ecologically alien species and elimination of invasive species, including black locust, red oak Quercus rubra, Douglas fir Pseudotsuga taxifolia, and black cherry Padus serotina,

- The establishment of protection zones for spleenworts, mainly in the area of the Kiełczyn Hills;

- In the case of tourism, it is recommended to first develop the various forms of cognitive tourism: ecotourism, geotourism, and sightseeing-oriented tourism, as well as hiking, cycling, and horse-riding tourism;

- Equipping the tourist trails and educational trails with structural elements for tourist traffic, including gates, display boards, road signs, roofed picnic and rest sites, benches, footbridges, decks, viewing platforms, etc., provided that such measures do not degrade the natural or landscape value;

- The development of a spatial planning report for the park specifying the catalog of architectural solutions complying with the basic types of building constructions and selected structural elements.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tyrväinen, L.; Buchecker, M.; Degenhardt, B.; Vuletic, D. Evaluating the economic and social benefits of forest recreation and nature tourism. In European Forest Recreation and Tourism, 1st ed.; Bell, S., Simpson, M., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., Pröbstl, U., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, K.; Søndergaard Jensen, F.; Elers Koch, N. A review of forest recreation and human health in plantation forests. Ir. For. 2010, 67, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Janeczko, E.; Pniewska, J.; Bielinis, E. Forest tourism and recreation management in the Polish Bieszczady Mountains in the opinion of tourist guides. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinlay, J.; Gkoumas, V.; Holtvoeth, J.; Fuertes, R.F.A.; Bazhenova, E.; Benzoni, A.; Botsch, K.; Martel, C.C.; Sánchez, C.C.; Cervera, I.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the management of European protected areas and policy implications. Forests 2020, 11, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichlerová, M.; Önkal, D.; Bartlett, A.; Výbošt’ok, J.; Pichler, V. Variability in forest visit numbers in different regions and population segments before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jũrmalis, E.; Lībiete, Z.; Bãrdule, A. Outdoor recreation habits of people in Latvia: General trends, and changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikus, A.; Rothert, M. Turystyka w Lasach Państwowych–koncepcje, kierunki oraz perspektywy rozwoju. In Turystyka i Rekreacja w Lasach Państwowego Gospodarstwa Leśnego Lasy Państwowe na Przykładzie Dolnego Śląska, 1st ed.; Czerniak, A., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nita, J.; Myga-Piątek, U. Krajobrazowe kierunki zagospodarowania terenów pogórniczych. Prz. Geol. 2006, 54, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbowski, A.; Krzeczyńska, M.; Woźniak, P. Ochrona starych kamieniołomów jako obiektów przyrodniczych o walorach naukowych, edukacyjnych i geoturystycznych–teoria a praktyka. Hered. Minariorum 2017, 4, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borišev, M.; Pajević, S.; Nikolić, N.; Pilipović, A.; Arsenov, D.; Župunski, M. Mine site restoration using silvicultural approach. In Bio-Geotechnologies for Mine Site Rehabilitation, 1st ed.; Prasad, M.N.V., de Campos Favas, P.J., Maiti, S.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, O.; Clemente, A.S.; Correia, A.I.; Miiguas, C.; Carolino, M.; Afonso, A.C.; Martins-Loução, M.A. Quarry rehabilitation: A case study. Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2001, 46, 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Reintam, L.; Kaar, E. Natural and man-made afforestation of sandy-textured quarry detritus of open-cast oil-shale mining. Balt. For. 2002, 8, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Casselman, C.N.; Fox, T.R.; Burger, J.A.; Jones, A.T.; Galbraith, J.M. Effects of silvicultural treatments on survival and growth of trees planted on reclaimed mine lands in the Appalachians. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 223, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.E.; Landhäusser, S.M.; Skousen, J.; Franklin, J.; Frouz, J.; Hall, S.; Jacobs, D.F.; Quideau, S. Forest restoration following surface mining disturbance: Challenges and solutions. New For. 2015, 46, 703–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetková, P.; Tichý, L.; Háněl, L.; Kukla, J.; Vicentini, F.; Frouz, J. The effect of soil and plant material transplants on vegetation and soil biota during forest restoration in a limestone quarry: A case study. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 158, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanska, J.; Twardowska, I. Distribution and environmental impact of coal-mining wastes in Upper Silesia, Poland. Environ. Geol. 1999, 38, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.A.; Johnson, M.S. Ecological restoration of land with particular reference to the mining of metals and industrial minerals: A review of theory and practice. Environ. Rev. 2002, 10, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawor, Ł. Wybrane problemy prawne dotyczące rekultywacji zwałowisk pogórniczych w Zagłębiu Ruhry i Górnośląskim Zagłębiu Węglowym. Chosen legal problems concerning reclamation of post mining dumping grounds in Ruhr Basin and Upper Silesian Coal Basin. Górnictwo I Geol. 2012, 7, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zástěrová, P.; Marschalko, M.; Niemiec, D.; Durd’ák, J.; Bulko, R.; Vlček, J. Analysis of possibilities of reclamation waste dumps after coal mining. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrobala, V.; Popovych, V.; Tyndyk, O.; Voloshchyshyn, A. Chemical pollution peculiarities of the Nadiya mine rock dumps in the Chervonohrad Mining District, Ukraine. Min. Miner. Depos. 2022, 16, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migon, E.; Migon, P. Geoheritage and cultural heritage—A review of recurrent and interlinked themes. Geosciences 2022, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranová, L.; Balej, M.; Raška, P. Assessing the geotourism potential of abandoned quarries with multitemporal data (České Středohoří Mts., Czechia). GeoScape 2017, 11, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Coratza, P.; Hobléa, F. Current Research on Geomorphosites. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Coratza, P. Scientific research on geomorphosites. A review of the activities of the IAG Working Group on Geomorphosites over the last twelve years. Geogr. Fis. Dinam. Quat. 2013, 36, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M. Geomorphosites: Concepts, methods and examples of geomorphological survey. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Panizza, M. Geomorphosites: Definition, assessment and mapping. An introduction. Géomorphologie Relief Process. Environ. 2005, 3, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalikowa, L.; Kirchner, K.; Kuda, F.; Machar, I. The role of anthropogenic landforms in sustainable landscape management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEOsfera, Jaworzno. Available online: https://slaskie.travel/poi/508313/osrodek-edukacji-ekologiczno-geologicznej-geosfera-i-kamieniolom-sodowa-gora-w-j (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Kielce-Kadzielnia Quarry Complex. Available online: https://geonatura-kielce.pl/about/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- European Centre for Geological Education–Chęciny. Available online: https://www.eceg.uw.edu.pl/en/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- St. Margarethen Quarry Opera. Available online: https://www.operimsteinbruch.at/EN/venues/steinbruch (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Talento, K.; Amado, M.; Kullberg, J.C. Quarries: From abandoned to renewed places. Land 2020, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučas, J.; Kučinskienė, J. Adaptation of dolomite quarry for entertainment. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2011, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kalybekov, T.; Sandibekov, M.; Rysbekov, K. Substantiation of ways to reclaim the space of the previously mined-out quarries for the recreational purposes. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 123, 01004. Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2019/49/e3sconf_usme2019_01004/e3sconf_usme2019_01004.html (accessed on 26 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ku, J.; Park, H.-D. Analysis of photovoltaic potential of unused space to utilize abandoned stone quarry. Tunn. Undergr. Space 2021, 31, 534–548. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Choi, Y. Analysis of the potential for use of floating photovoltaic systems on mine pit lakes: Case study at the Ssangyong open-pit limestone mine in Korea. Energies 2016, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUGiK Geoportal. Available online: www.geoportal.gov.pl (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Solon, J.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Bidłasik, M.; Richling, A. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland: Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary spatial data. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P. Ślężański Park Krajobrazowy; Dolnośląski Zespół Parków Krajobrazowych: Wrocław, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Szkop, Z. Badanie willingness to pay turystów odwiedzających Ślężański Park Krajobrazowy. Study of willingness to pay of tourists visiting Ślęża Landscape Park. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2015, 409, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyk, W.; Dołęga, A.; Pęgowska, P.; Zawiła-Piłat, M.; Haromszeki, Ł.; Wilk, A. Koncepcja Subregionalnego Produktu Turystycznego “Ślęża”; org.turysta Report; Dolnośląska Organizacja Turystyczna: Wrocław, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sztromwasser, E.; Mydłowski, A. Detailed Geological Map of Poland 1:50,000 (SMGP), Sheet: Sobótka (799); National Geological Institute–National Research Institute, Ministry of Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cymerman, Z.; Sztromwasser, E. Detailed Geological Map of Poland 1:50,000 (SMGP), Sheet: Dzierżoniów (835); National Geological Institute–National Research Institute, Ministry of Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Glapa, W.; Sroga, C. Rozwój Wykorzystania Granitoidów Masywu Strzegom–Sobótka w Latach 2003–2012 w Budownictwie i Drogownictwie; Zesz. Nauk. IGSMiE PAN, 85: Kraków, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dubińska, E.; Gunia, P. The Sudetic ophiolite: Current view on its geodynamic model. Geol. Q. 1997, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J.F. Ophiolite obduction. Tectonophysics 1976, 31, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, Y.; Furnes, H. Ophiolite genesis and global tectonics: Geochemical and tectonic fingerprinting of ancient oceanic lithosphere. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2011, 123, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubińska, E.; Nejbert, K.; Bylina, P. Oliwiny ze skał ultramaficznych masywu Jordanów–Gogołów (ofiolit sudecki)—Zapis zróżnicowanych procesów geologicznych. Prz. Geol. 2010, 58, 506–515. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtulek, P.M.; Schulz, B.; Klemd, R.; Gil, G.; Dajek, M.; Delura, K. The Central-Sudetic ophiolites–Remnants of the SSZ-type Devonian oceanic lithosphere in the European part of the Variscan Orogen. Gondwana Res. 2022, 105, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowski, P.; Mazur, S. Collage tectonics in the northeasternmost part of the Variscan Belt: The Sudetes, Bohemian Massif. In Palaeozoic Amalgamation of Central Europe; Winchester, J.A., Pharaoh, T.C., Verniers, J., Eds.; Geological Society Special Publications 201; The Geological Society: London, UK, 2002; pp. 237–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kryza, R.; Pin, C. The Central-Sudetic ophiolites (SW Poland): Petrogenetic issues, geochronology and palaeotectonic implications. Gondwana Res. 2010, 17, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdankiewicz, M.; Kryza, R.; Turniak, K.; Ovtcharova, M.; Schaltegger, U. The Central Sudetic Ophiolite (European Variscan Belt): Precise U-Pb zircon dating and geotectonic implications. Geol. Mag. 2020, 158, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRTM Source, USGS. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Plissart, G.; Monnier, C.; Diot, H.; Mărunţiu, M.; Berger, J.; Triantafyllou, A. Petrology, geochemistry and Sm-Nd analyses on the Balkan-Carpathian Ophiolite (BCO–Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria): Remnants of a Devonian back-arc basin in the easternmost part of the Variscan domain. J. Geodyn. 2017, 105, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Catalán, J.R.; Collett, S.; Schulmann, K.; Aleksandrowski, P.; Mazur, S. Correlation of allochthonous terranes and major tectonostratigraphic domains between NW Iberia and the Bohemian Massif, European Variscan belt. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2020, 109, 1105–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, W. Próba lokalizacji ośrodków produkcyjnych toporów ślężańskich w świetle badań petroarcheologicznych. Przegl. Arch. 1988, 35, 101–138. [Google Scholar]

- Majerowicz, A.; Skoczylas, J.; Wójcik, A. Petroarcheologia i rozwój jej badań na Dolnym Śląsku. Petroarchaeological research in Lower Silesia. Prz. Geol. 1999, 47, 638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska, E.; Gunia, P. The use of Lower-Silesian serpentinites in the early middle-ages. Śląskie Spraw. Archeol. 2020, 62, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupecki, L.P. Ślęża, Radunia, Wieżyca. Miejsca kultu pogańskiego Słowian w średniowieczu. Kwart. Hist. 1992, 2, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, Z. Problem istnienia celtyckiego nemetonu na Ślęży. Przegląd Archeol. 2004, 52, 131–183. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, G. Sprawozdanie z badan wczesnośredniowiecznych kamieniołomów na stokach Góry Slęży, w pobliżu miejscowości Sobótka-Górka, w 1963 roku. Spraw. Archeol. 1965, 17, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska, E. Wydobycie i Dystrybucja Surowców Kamiennych We Wczesnym Średniowieczu na Dolnym Śląsku; Instytut Archeologii Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska, E.; Gunia, P.; Borowski, M. Production and distribution of rotary quernstones from quarries in southwestern Poland in the early Middle Ages. AmS-Skrifter 2014, 24, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chanas, R. Ślęża. Śląski Olimp. Przewodnik; Sport i Turystyka: Warszawa, Poland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Taras, E. Region Ślężański Skarbnicą Skał i Minerałów, Ewenement Geologiczny w Przyrodzie; AVR ANTEX: Sobótka, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, M.W.; Mazurek, S. Wybrane, nowe propozycje atrakcji geoturystycznych z Dolnego Śląska. Geoturystyka 2010, 3–4, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, E.; Lorenc, M.W. Problem niewykorzystanego potencjału dawnych kamieniołomów na przykładzie Wieżycy i Chwałkowa (Dolny Śląsk). Geoturystyka 2010, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Żaba, J.; Janeczek, J.; Kozłowski, K. Zbieramy Minerały i Skały. Przewodnik po Dolnym Śląsku; Wyd. Geologiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Management Plan for the Miękinia Forest District for the Period from January 1, 2022 to December 31 2031 Nature Conservation Program. Plan Urządzenia lasu dla Nadleśnictwa Miękinia na Okres od 1 Stycznia 2022 r. do 31 Grudnia 2031 r. Program Ochrony Przyrody; RDLP we Wrocławiu, BULiGL w Brzegu: Brzeg, Polska, 2022.

- Forest Data Bank. Available online: https://www.bdl.lasy.gov.pl/portal/mapy (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- The Resolution of the Provincial Council in Wrocław of 8.06.1988 on the Establishment of the Ślęża Landscape Park together with Its Buffer Zone. Uchwała nr XXIV/155/88 Wojewódzkiej Rady Narodowej we Wrocławiu z dn. 8.06.1988 r. w Sprawie Utworzenia Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego Wraz z Otuliną (Dz. Urz. Woj. Wroc. Nr 13 póz. 185). Available online: https://crfop.gdos.gov.pl/CRFOP/widok/viewparkkrajobrazowy.jsf?fop=PL.ZIPOP.1393.PK.150 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Krajewski, P.; Mastalska-Cetera, B. Zmiany krajobrazu gminy Sobótka na obszarze Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Krajobrazy rekreacyjne–kształtowanie, wykorzystanie, transformacja. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, 27, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution of the Provincial Governor of the Lower Silesia Province of 4 April 2007 on the Ślęża Landscape Park, 2007. Rozporządzenie Wojewody Dolnośląskiego z dnia 4 kwietnia 2007 r. w Sprawie Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Dz. Urz. Woj. Doln. Nr 74, Poz. 1105. Available online: http://oi.uwoj.wroc.pl/dzienniki/Dzienniki_2007/Dz_U_Nr_94.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- The Protection Plan for the Ślęża Landscape Park. Plan Ochrony dla Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego. Załącznik nr 1 do Uchwały nr XVI/331/11 Sejmiku Województwa Dolnośląskiego z Dnia 27 Października 2011 r. Dz. Urz. z 2011 r. Nr 251, poz. 4508. Available online: https://crfop.gdos.gov.pl/CRFOP/widok/viewparkkrajobrazowy.jsf?fop=PL.ZIPOP.1393.PK.150 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Plan of Conservation Tasks of the Natura 2000 Area PLH020021 Kiełczyn Hills in Lower Silesia Province for the Years 2014–2024. Plan Zadań Ochronnych Obszaru Natura 2000 PLH020021 Wzgórza Kiełczyńskie w Województwie Dolnośląskim na Lata 2014−2024. Regionalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska We Wrocławiu. Available online: http://wroclaw.rdos.gov.pl/projekt-planu-zadan-ochronnych-25 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Ordinance of the Regional Director of Environmental Protection in Wrocław Dated 11 July 2014 on Establishing a Plan of Conservation Tasks for the Natura 2000 Area Ślęza Massif PLH020040.Zarządzenie Regionalnego Dyrektora Ochrony Środowiska We Wrocławiu z Dnia 11 Lipca 2014 r. w Sprawie Ustanowienia Planu Zadań Ochronnych Dla Obszaru Natura 2000 Masyw Ślęży PLH020040. Dz. Urz. Województwa Dolnośląskiego poz. 3244. Available online: http://wroclaw.rdos.gov.pl/plh020040-masyw-slezy (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Świerkosz, K. Siedliska przyrodnicze Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego–stan zachowania i zagrożenia. In Istniejące i Potencjalne Zagrożenia Funkcjonowania Parków Krajobrazowych w Polsce. Konferencja Naukowa z Okazji 25-Lecia Ślężańskiego Parku Krajobrazowego; Śniegucki, P., Krajewski, P., Eds.; DZPK: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Żołnierz, L. Monitoring Gatunków i Siedlisk Przyrodniczych ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Specjalnych Obszarów Ochrony Siedlisk Natura 2000. Zanokcica Serpentynowa Asplenium Adulterinum 2012, 4066. Available online: https://siedliska.gios.gov.pl/images/pliki_pdf/wyniki/2009-2011/dla_roslin/Zanokcica-serpentynowa-Asplenium-adulterinum.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Szczęśniak, E. Zanokcica ciemna Asplenium adiantum-nigrum L. na Wzgórzach Kiełczyńskich (Masyw Ślęży). Przyr. Sudet. 2019, 22, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniański, G.Z.; Piątek, G.; Szmalec, T. Stan ochrony gatunków roślin w Polsce w roku 2021. Biul. Monit. Przyr. 2022, 25, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Baczyńska, E.; Lorenc, M.W.; Kaźmierczak, U. The landscape attractiveness of abandoned quarries. Geoheritage 2017, 10, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ważyński, B. Atrakcyjność terenów do wypoczynku. In Urządzanie i Zagospodarowanie Lasu dla Potrzeb Turystyki i Rekreacji; Ważyński, B., Ed.; Wyd. Akademii Rolniczej im. Augusta Cieszkowskiego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 1997; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Golos, P. Social importance of public forest functions—Desirable for recreation model of tree stand and forest. Społeczne znaczenie publicznych funkcji lasu–pożądany dla rekreacji i wypoczynku model drzewostanu i lasu. Leśne Pr. Badaw. 2010, 71, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. The attractiveness of forests: Preferences and perceptions in a mountain community in Italy. Ann. For. Res. 2015, 58, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bańkowski, J.; Sroga, R.; Basa, K.; Czerniak, A.; Beker, C. Koncepcja zagospodarowania turystycznego dla Leśnego Kompleksu Promocyjnego “Lasy Doliny Baryczy”–przykładowy operat turystyczny. In Turystyka i Rekreacja w Lasach Państwowego Gospodarstwa Leśnego Lasy Państwowe na Przykładzie Dolnego Śląska, 1st ed.; Czerniak, A., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wajchman-Switalska, S. Typ siedliskowy lasu i jego waloryzacja na potrzeby rekreacji w lasach. Acta Sci. Pol.-Rum Silvarum Colendarum Ratio Et Ind. Lignaria 2019, 8, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, G.; Csullog, G. The role of ecotourism and geoheritage in the spatial development of former mining regions. In Post-Mining Regions in Central Europe: Problems, Potentials, Possibilities, 1st ed.; Fischer, W., Wirth, P., Cernic-Mali, B., Eds.; Oekom Verlag GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity, geoheritage and geoconservation for society. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2019, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivenga, M.; Cavalcante, F.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Palladino, G.; Prosser, G. Geoheritage: The foundation for sustainable geotourism. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1367–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E. Geoheritage, geotourism and the cultural landscape: Enhancing the visitor experience and promoting geoconservation. Geosciences 2018, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocx, M.; Semeniuk, V. Geoheritage and geoconservation-history, definition, scope and scale. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2007, 90, 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bąbelewska, A.; Musielińska, R.; Śliwińska-Wyrzychowska, A.; Bogdanowicz, M.; Witkowska, E. Edukacyjna rola nieczynnego kamieniołomu “Lipówka” w Rudnikach koło Częstochowy. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2014, 26, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gajek, G.; Zgłobicki, W.; Kołodyńska-Gawrysiak, R. Geoeducational value of quarries located within the Małopolska Vistula River gap (E Poland). Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druguet, E.; Passchier, C.W.; Pennacchioni, G.; Carreras, J. Geoethical education: A critical issue for geoconservation. Episodes 2013, 36, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocx, M.; Semeniuk, V. The “8Gs”—A blueprint for geoheritage, geoconservation, geo-education and geotourism. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 66, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescotti, P.; Castello, G.; Briguglio, A.; Caprioglio, M.C.; Crispini, L.; Firpo, M. Geosite assessment in the Beigua UNESCO Global Geopark (Liguria, Italy): A case study in linking geoheritage with education, tourism, and community involvement. Land 2022, 11, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfo, F.; Balestro, G.; Borghi, A.; Castelli, D.; Ferrando, S.; Groppo, C.; Mosca, P.; Rossetti, P. The Monviso Ophiolite Geopark, a symbol of the Alpine chain and geological heritage in Piemonte, Italy. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory, Volume 8—Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Lollino, G., Giordan, D., Marunteanu, C., Christaras, B., Yoshinori, I., Margottini, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quarry Traits | The Site | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistoric | Górka 1 | “White Cows” 1 | Sady | Quartz Mountain 2 | Przemiłów | Winna Mountain 2 | Słupice Mountain | Kiełczyn 2 | |

| No. in the Text and Figure 4 | |||||||||

| 4.1.1. | 4.1.2. | 4.2.1. | 4.2.2. | 4.2.3. | 4.3.1. | 4.3.2. | 4.3.3. | 4.3.4. | |

| Excavation area (m2) | 3800 | 1485 (N) 1110 (S) | 1700 (N), 3800 (S) | 1300 | 4450 | 3865 | 2950 | 4400 | 4700 |

| Excavation perimeter (m) | 316 | 170 (N) 135 (S) | 375 (N) 475 (S) | 205 | 300 | 263 | 250 | 255 | 325 |

| Maximum length (m) | 93 | 57 (N) 50 (S) | 100 (N) 165 (S) | 58 | 117 | 106 | 98 | 64 | 80 |

| Maximum width (m) | 65 | 33 (N) 33 (S) | 28 (N) 38 (S) | 34 | 47 | 52 | 36 | 62 | 72 |

| Number of quarry faces, orientation | 3: N, S, E | 4: NE, SE, W, NW 3: NE, SW, NW | 1: NE | 3: NE, NW, S | 3: NE, SE, SW | 3: NE, SE, SW | 3: W, N, E | 3: W, N, E | 3: NW, NE, SE |

| Maximum height of rock faces (m) | 12 | 5,5 (N) 4,8 (S) | 14 (N) 14 (S) | 20–30 | 10 (L) 15 (U) | 8 | 7.5 (L) 2.5 (U) | 17 (L) 2.6 (U) | 17 |

| Tilt of the faces | 35–60° | 29–69° (N) 13–51° (S) | 36–44° (N) 35–55° (S) | 33–58° | 45–65 (L) 35–38 (U) | 18–53° | 30–59 (L) 24–46 (U) | 31–43 | 28–48 (L) 21–36 (U) |

| Number of production levels | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Elevation range (m.a.s.l.) | 252–276 | 226–234 | 203–233 | 268–306 | 319–347 | 245–255 | 290–299 | 323–348 | 316–337 |

| Position on the slope | W | N | SW | SW | NW | W | E | S | SW |

| Criteria for Evaluating Suitability for Tourist Use | Points-Based Assessment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistoric | Górka | “White Cows” | Sady | Quartz Mountain | Przemiłów | Winna Mountain | Słupice Mountain | Kiełczyn | |

| No. in the Text and Figure 4 | |||||||||

| Section 4.1.1. | Section 4.1.2. | Section 4.2.1. | Section 4.2.2. | Section 4.2.3. | Section 4.3.1. | Section 4.3.2. | Section 4.3.3. | Section 4.3.4. | |

| Interesting shape of working, interesting surface topography, and presence of working floors 1—less impressive, 2—moderately impressive, 3—impressive | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Height of rock faces and steepness—visual effect 1—less impressive, 2—moderately impressive, 3—impressive | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| State of preservation of rock faces and accessibility for direct geological observation (ability to observe mineralization, petrographic, tectonic features of the rock, degree of weathering, presence of debris, and screes) 1—bad, 2—moderate, 3—good | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Exposure/visibility of rock faces—degree of their overgrowth with vegetation 1—bad, 2—moderate, 3—good | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Status of expansion of natural plant succession within the excavation 1—dense cover of uncontrolled vegetation, significantly hindering the penetration of the excavation; 2—medium dense vegetation cover; 3—vegetation well integrated into the landscape | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Presence of invasive plant specie and excessive growth of undesirable species (nettle and brambles) 1—yes, 2—no | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Presence of surface waters 1—no, 2—yes | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Presence of mature/precious stand in the working and presence of trees with impressive development forms 1—no precious/impressive trees; 2—presence of some impressive trees; 3—many old/precious, impressive trees | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Instability of steep rock faces—the need for safety measures 1—yes, 2—no | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Interesting stand/interesting habitats in the quarry surroundings 1—no, 2—yes | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Vicinity of tourist trail 1—far from the trail, 2—short distance from the trail; 3—next to the trail | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Accessibility, location near a public road 1—far from the road, 2—short distance from the road, 3—next to the road | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Other value (vicinity of other interesting cultural or historical objects, etc. (within the radius of max. 500 m)) 1—no other attractions, 2—one interesting object, 3—several attractions | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Possibility of placing small infrastructure (bench, shed, footbridge, and educational board) 1—no, 2—yes, but outside only, 3—yes, inside the excavation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Instability of steep rock faces—the need for safety measures 1—yes, 2—no | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Final score max. 40 (100%) | 32 | 33 | 23 | 25 | 34 | 31 | 28 | 27 | 29 |

| 80% | 82.5% | 57.5% | 62.5% | 85% | 77.5% | 70% | 67.5% | 72.5% | |

| High score (≥80%) | • | • | • | ||||||

| Medium score (60–79%) | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Low score (<60%) | • | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurowska, E.E.; Czerniak, A.; Bańkowski, J. The Rationale for Restoration of Abandoned Quarries in Forests of the Ślęża Massif (Poland) in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Forest Environment Protection. Forests 2023, 14, 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071386

Kurowska EE, Czerniak A, Bańkowski J. The Rationale for Restoration of Abandoned Quarries in Forests of the Ślęża Massif (Poland) in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Forest Environment Protection. Forests. 2023; 14(7):1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071386

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurowska, Ewa E., Andrzej Czerniak, and Janusz Bańkowski. 2023. "The Rationale for Restoration of Abandoned Quarries in Forests of the Ślęża Massif (Poland) in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Forest Environment Protection" Forests 14, no. 7: 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071386

APA StyleKurowska, E. E., Czerniak, A., & Bańkowski, J. (2023). The Rationale for Restoration of Abandoned Quarries in Forests of the Ślęża Massif (Poland) in the Context of Sustainable Tourism and Forest Environment Protection. Forests, 14(7), 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071386