Heat-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior among Indonesian Forestry Workers and Farmers: Implications for Occupational Health Promotion in the Face of Climate Change Impacts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

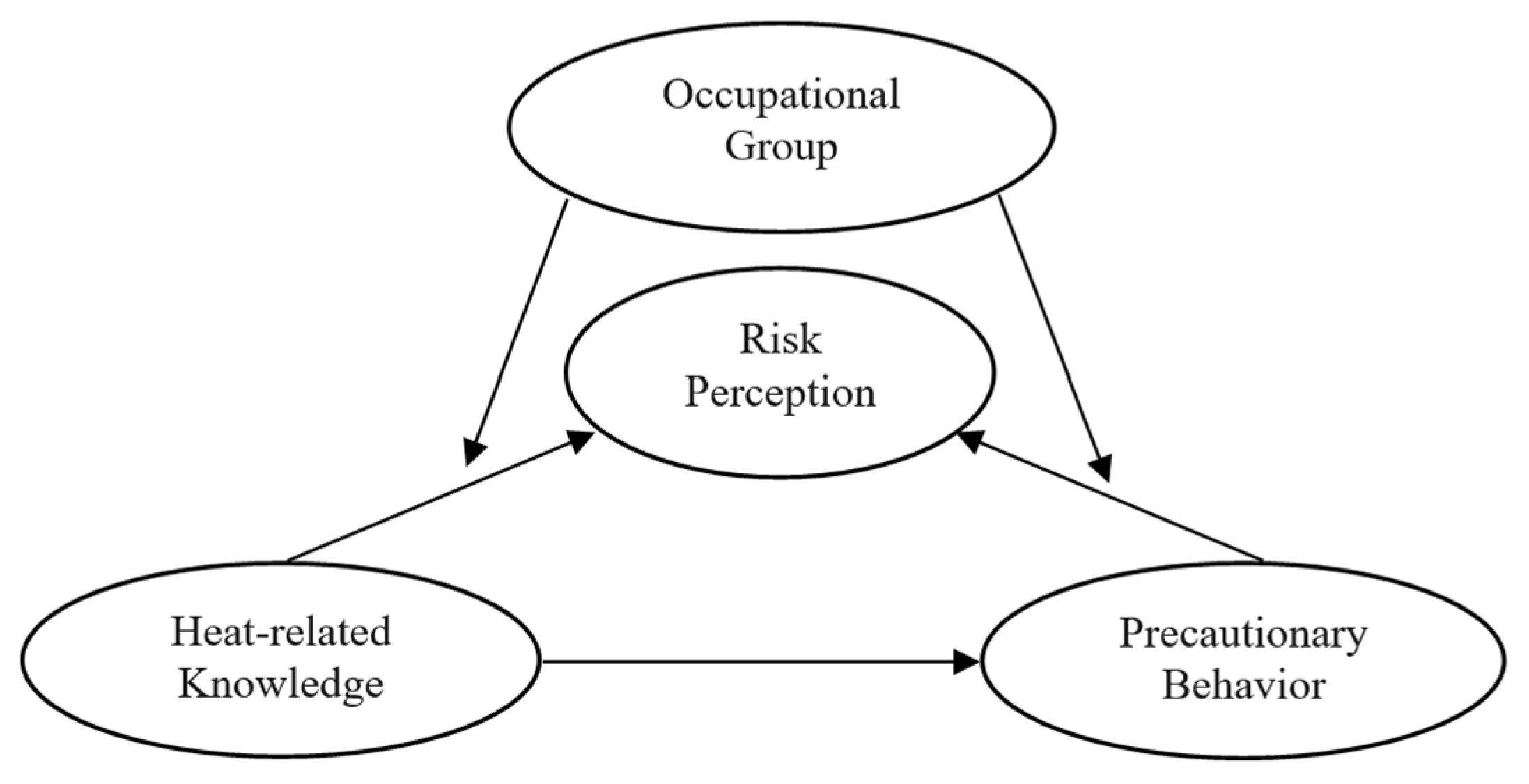

2.1. Hypothesis

2.2. Survey and Survey Participants

2.3. Models

2.4. Latent Variables

3. Results

3.1. Structural Model Evaluation

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Preparation: | |||||||

| 1. Identify a suitable interviewee who fits the criteria and is willing to participate. 2. Introduce yourself and describe the goal of the study and methods of data collection. Use the Informed Consent Form to guide your explanation and ensure the respondent fully understand the study’s purpose and procedures. 3. Obtain informed consent from the interviewee by having them sign the Informed Consent Form. Ensure they are aware of their rights as participant, including their ability to withdraw from the study at any time. 4. Begin recording the interview session and assign a unique respondent code: GROUP-NO-LOCUS-GENDER, to the recording to maintain confidentiality and anonymity. 5. For Part 2: Ask the interviewer to indicate each statement as "TRUE" or "FALSE" based on their perception. The answer choices listed in the interview guide are the key to the expected answers. 6. For Part 3–5: Ask the interviewee to rate their attitude towards the given statements using a 1–7 scale, while ensuring that you had provide a clear explanation of the scale to ensure consistency in the rating pattern. 7. Proceed with the interview. | |||||||

| Interview record identity | |||||||

| 1. Date of interview:……………………(mm/dd/yy). | |||||||

| 2. Name of interviewer: ………………………. | |||||||

| 3. Interviewee’s code: ……………………………. | |||||||

| Part 1. General information | |||||||

| 1. Name: Please provide the interviewee’s full name. | |||||||

| 2. Age: Please indicate the interviewee’s age: ………………years. | |||||||

| 3. Gender: Please select “M” for male or “F” for female. | |||||||

| 4. Educational attainment: What is the highest educational attainment? Please select from the following options: none; elementary school/equivalent graduate; middle school/equivalent graduate; high school/equivalent graduate; college/university. | |||||||

| 5. Marital status: Please select “Single” or “Married”. | |||||||

| 6. Work experience …………………… year. | |||||||

| 7. Average working hours ……………………………… hours/day ………… days/week. | |||||||

| 8. Work schedule: The start and finish times for a typical workday. Starting work at …………………………… finish at ………………………………………. | |||||||

| 9. Job description ……………………………………………………………………………………. | |||||||

| Part 2. Heat-related knowledge (K) | |||||||

| Symptoms (K2) (adopted from Riccò et al. 2020 [10]) | |||||||

| When you work under heat exposure: | |||||||

| 1. Excessive thirst is not a symptom of mild overheating. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 2. Headache is a symptom of mild overheating. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 3. Muscle cramps are a symptom of mild overheating. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 4. Dizziness is a symptom of mild overheating. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 5. High fever is a symptom of severe overheating. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 6. Fainting is not a symptom of severe overheating. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 7. Fast heartbeat is a symptom of severe overheating. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 8. The dark color of urine is a sign of dehydration. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| Prevention and first aid (K3) (adopted from Riccò et al. 2020 [10]) | |||||||

| When you feel work under sun exposure or experience overheated: | |||||||

| 1. Lowering body temperature can be effectively achieved by drinking coffee instead of water. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 2. Drinking hot water can significantly reduce your body temperature. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 3. To reduce body temperature effectively, pouring cold water over the body can be an effective method. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 4. Loose clothing does not help the body to lower its temperature effectively. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 5. Cotton is an excellent material for workwear as it absorbs sweat well. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 6. Polyester outerwear can effectively block the sun’s rays from reaching the skin surface beneath your clothes. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 7. Wearing loose outerwear made of dark-colored polyester material and pairing it with a light-colored cotton shirt as an inner layer can help protect the body from excessive heat. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 8. When working in hot environments, it is not advisable to drink cold (cool) water as it can be harmful to the body. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 9. Seeking immediate shelter can relieve the symptoms of health problems caused by mild exposure to heat. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 10. In the event of a patient fainting due to heat, it is recommended to cover them with a thick blanket or cloth. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 11. To prevent health issues caused by overheating, it is advisable to reduce working hours when the temperature is high. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 12. Working early in the morning can effectively prevent heat-related health issues. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 13. Mild heat exposure can exacerbate health problems, but seeking shelter immediately can help. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 14. Wearing a wide-brimmed hat can effectively mitigate the negative effects of workplace heat. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| Heat exposure and work performance (K4) | |||||||

| 1. Increasingly intense temperatures and exposure to the sun cause a decrease in a person’s ability to complete work. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 2. Health problems due to heat exposure will cause a decrease in one’s ability to work. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 3. Prolonged work time can reduce productivity. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 4. Working under excessive heat exposure can negatively impact work quality. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 5. Reduced work performance may result in decreased income. | True/False | (True) | |||||

| 6. A decrease in work performance may not lead to direct losses for the worker. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 7. Decreased work performance may not necessarily result in losses for the employer or landowner. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| 8. When it’s very hot outside, working rapidly is the best way to keep up productivity. | True/False | (False) | |||||

| Part 3. Risk perception: dread risk factor (DF) | |||||||

| Controllability (DF1) | How well can you control the negative health effects of heat exposure at work? | ||||||

Highly capable of control  Uncontrollable at all Uncontrollable at all | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Dread (DF2) | How much do you dread the health risks associated with heat exposure? | ||||||

Not at all horrible  Extremely horrible Extremely horrible | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Severity (DF3) | How severe are the health problems caused by exposure to heat? | ||||||

Not at all severe  Extremely severe Extremely severe | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Part 4. Risk perception: unknown risk factor (UF) | |||||||

| Observability (UF1) | How clear are the adverse effects of exposure to heat? | ||||||

Very obvious  Not at all obvious Not at all obvious | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Part 5. Precautionary behavior (PB) | |||||||

| How much do you agree with these heat-protection statements? | |||||||

| Items | Absolutely necessary  Completely unnecessary Completely unnecessary | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| PB 1. I start my workday early in the morning. | |||||||

| PB 2. I collaborate with my coworkers to share work shifts. | |||||||

| PB 3. I have reduced my work hours while increasing the number of workdays. | |||||||

| PB 4. I have begun to involve more of my coworkers in our daily tasks. | |||||||

| PB 6. To avoid overheating, I take a short break whenever I feel hot. | |||||||

| PB 7. I wear work clothes made from materials that easily absorb sweat. | |||||||

| PB 9. I prefer wearing whole-body, layered clothing, and trousers for added protection. | |||||||

| PB 13. When it’s hot, I seek shade to stay cool. | |||||||

| PB 15. I have requested my boss to provide a first aid kit at the workplace. | |||||||

| PB 16. I have asked my boss to establish emergency protocols in case of emergency. | |||||||

| Variable | VIF | Variable | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of signs of health concerns associated with extreme heat-exposure in the workplace (K2) | 1.049 | I have reduced my work hours while increasing the number of workdays (PB3) | 1.257 |

| Heat exposure avoidance and first aid (K3) | 1.087 | I have begun to involve more of my coworkers in our daily tasks (PB4) | 1.344 |

| Heat exposure effect on work performance (K4) | 1.126 | To avoid overheating, I take a short break whenever I feel hot (PB6) | 1.441 |

| Controllability (DF1) | 1.118 | I wear work clothes made from materials that easily absorb sweat (PB7) | 1.777 |

| Dread (DF2) | 1.58 | I prefer wearing whole-body, layered clothing, and trousers for added protection (PB9) | 1.404 |

| Severity (DF3) | 1.44 | When it’s hot, I seek shade to stay cool (PB13) | 1.61 |

| Observability (UF1) | 1 | I have requested my boss to provide a first aid kit at the workplace (PB15) | 1.871 |

| I start my workday early in the morning (PB1) | 1.335 | I have asked my boss to establish emergency protocols in case of emergency (PB16) | 1.741 |

| I collaborate with my coworkers to share work shifts (PB2) | 1.357 |

| Variable | R2 | R2 Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| Dread risk factors (DF) | 0.07 | 0.068 |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | 0.407 | 0.403 |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| Variable | SSO | SSE | Q2 (1-SSE/SSO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dread risk factors (DF) | 1275.00 | 1063.2 | 0.166 |

| Heat-related knowledge (K) | 1275.00 | 1228.2 | 0.037 |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | 4250.00 | 3365.8 | 0.208 |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | 425 | 1 |

| Value | Saturated Model | Estimated Model |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.097 | 0.098 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.568 | 0.561 |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.K.R.; Wilby, R.L.; Murphy, C. Communicating the deadly consequences of global warming for human heat stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.; Dousset, B.; Caldwell, I.R.; Powell, F.E.; Geronimo, R.C.; Bielecki, C.R.; Counsell, C.W.W.; Dietrich, B.S.; Johnston, E.T.; Louis, L.V.; et al. Global risk of deadly heat. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi, dan Geofisika (BMKG), Perubahan Iklim: Proyeksi Perubahan Iklim. 2022. Available online: https://www.bmkg.go.id/iklim/?p=proyeksi-perubahan-iklim (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- BPS. Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2013; BPS: Viera, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- BPS. Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2021; BPS: Viera, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Briggs, D.; Freyberg, C.; Lemke, B.; Otto, M.; Hyatt, O. Heat, Human Performance, and Occupational Health: A Key Issue for the Assessment of Global Climate Change Impacts. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oppermann, E.; Kjellstrom, T.; Lemke, B.; Otto, M.; Lee, J.K.W. Establishing intensifying chronic exposure to extreme heat as a slow onset event with implications for health, wellbeing, productivity, society and economy. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constance, J.; Shandro, B. Heat-related Illness. In A Practical Guide to Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Caring for Children in the Emergency Department; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 234–236. [Google Scholar]

- Riccò, M.; Razio, B.; Poletti, L.; Panato, C.; Balzarini, F.; Mezzoiuso, A.G.; Vezzosi, L. Risk perception of heat related disorders on the workplaces: A survey among health and safety representatives from the autonomous province of Trento, Northeastern Italy. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, E48–E59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Varghese, B.M.; Hansen, A.; Bi, P.; Pisaniello, D. Are workers at risk of occupational injuries due to heat exposure? A comprehensive literature review. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 80–392. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeltz, M.T.; Petkova, E.P.; Gamble, J.L. Economic Burden of Hospitalizations for Heat-Related Illnesses in the United States, 2001–2010. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Butler, C.D. Climate Change, Health and Existential Risks to Civilization: A Comprehensive Review (1989–2013). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ILO. Working on a Warmer Planet: The Impact of HEAT Stress on Labour Productivity and Decent Work, Geneva. 2019. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_711919.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Pawson, S.M.; Brin, A.; Brockerhoff, E.G.; Lamb, D.; Payn, T.W.; Paquette, A.; Parrotta, J.A. Plantation forests, climate change and biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 1203–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvenue, C.; Running, S.W. Impacts of climate change on natural forest productivity—Evidence since the middle of the 20th century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, J.T.; Masuda, Y.J.; Wolff, N.H.; Calkins, M.; Seixas, N. Heat Exposure and Occupational Injuries: Review of the Literature and Implications. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model and Sick Role Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovi, E.Y.; Abbas, D.; Takahashi, T. Safety climate and risk perception of forestry workers: A case study of motor-manual tree felling in Indonesia. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girma, S.; Agenagnew, L.; Beressa, G.; Tesfaye, Y.; Alenko, A. Risk perception and precautionary health behavior toward COVID-19 among health professionals working in selected public university hospitals in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Gulanick, M.; Penckofer, S.; Kouba, J. Does Knowledge of Coronary Artery Calcium Affect Cardiovascular Risk Perception, Likelihood of Taking Action, and Health-Promoting Behavior Change? J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.Y.; Spitzmueller, C.; Cigularov, K.; Thomas, C.L. Linking safety knowledge to safety behaviours: A moderated mediation of supervisor and worker safety attitudes. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglioni, F.; Cartoux, M.; Dellagi, K.; Dalban, C.; Fianu, A.; Carrat, F.; Favier, F. The influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in Reunion Island: Knowledge, perceived risk and precautionary behaviour. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorfa, S.K.; Ottu, I.F.A.; Oguntayo, R.; Ayandele, O.; Kolawole, S.O.; Gandi, J.C.; Dangiwa, A.L.; Olapegba, P.O. COVID-19 Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior Among Nigerians: A Moderated Mediation Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566773. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566773 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraklı, M.; Küçükyavuz, S. Risk aversion to parameter uncertainty in Markov decision processes with an application to slow-onset disaster relief. IISE Trans. 2020, 52, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R. Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism. J. Common-Wealth Postcolonial Stud. 2011, 13, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Orom, H.; Cline, R.J.W.; Hernandez, T.; Berry-Bobovski, L.; Schwartz, A.G.; Ruckdeschel, J.C. A Typology of Communication Dynamics in Families Living a Slow-Motion Technological Disaster. J. Fam. Issues 2012, 33, 1299–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Staupe-Delgado, R. Progress, traditions and future directions in research on disasters involving slow-onset hazards. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 28, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BPS of Central Java Province, Suhu Udara 2018–2020. 2022. Available online: https://jateng.bps.go.id/indicator/151/694/1/suhu-udara.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- BPS of Cilegon City, Keadaan Suhu Udara per Bulan di Kota Cilegon Tahun 2013. 2013. Available online: https://cilegonkota.bps.go.id/statictable/2015/04/22/9/keadaan-suhu-udara-per-bulan-di-kota-cilegon-tahun-2013.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- BPS of Cilegon City, Suhu Udara Menurut Bulan di kota Cilegon 2017. 2017. Available online: https://cilegonkota.bps.go.id/indicator/151/75/1/suhu-udara-menurut-bulan-di-kota-cilegon-2017.html (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Peng, L.; Tan, J.; Lin, L.; Xu, D. Understanding sustainable disaster mitigation of stakeholder engagement: Risk perception, trust in public institutions, and disaster insurance. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26628355 (accessed on 28 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/a-primer-on-partial-least-squares-structural-equation-modeling-pls-sem/book244583 (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Ramayah, T.; Hwa, C.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkiran, N.K. Rise of the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: An Application in Banking. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Recent Advances in Banking and Finance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Gabrysch, S.; Lemke, B.; Dear, K. The “Hothaps” programme for assessing climate change impacts on occupational health and productivity: An invitation to carry out field studies. Glob. Health Action 2009, 2, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beckmann, S.K.; Hiete, M. Predictors Associated with Health-Related Heat Risk Perception of Urban Citizens in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ning, L.; Niu, J.; Bi, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Ning, N.; Liang, L.; Liu, A.; Hao, Y.; et al. The impacts of knowledge, risk perception, emotion and information on citizens protective behaviors during the outbreak of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwart, O.; Veldhuijzen, I.K.; Richardus, J.H.; Brug, J. Monitoring of risk perceptions and correlates of precautionary behaviour related to human avian influenza during 2006–2007 in the Netherlands: Results of seven consecutive surveys. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 16, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samadipour, E.; Ghardashi, F.; Nazarikamal, M.; Rakhshani, M. Perception risk, preventive behaviors and assessing the relationship between their various dimensions: A cross-sectional study in the COVID-19 peak period. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Do Lessons People Learn Determine Disaster Cognition and Preparedness? Psychol. Dev. Soc. J. 2007, 19, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brug, J.; Aro, A.R.; Oenema, A.; de Zwart, O.; Richardus, J.H.; Bishop, G.D. SARS Risk Perception, Knowledge, Precautions, and Information Sources, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2004, 10, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, C.A.; Satchell, L.P.; Fido, D.; Latzman, R.D. Functional Fear Predicts Public Health Compliance in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafede, M.; Levi, M.; Pietrafesa, E.; Binazzi, A.; Marinaccio, A.; Morabito, M.; Pinto, I.; de’ Donato, F.; Grasso, V.; Costantini, T.; et al. Workers’ Perception Heat Stress: Results from a Pilot Study Conducted in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mızrak, S.; Özdemir, A.; Aslan, R. Adaptation of hurricane risk perception scale to earthquake risk perception and determining the factors affecting womens earthquake risk perception. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 2241–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, M.L.; Alhakami, A.; Slovic, P.; Johnson, S.M. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2000, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skagerlund, K.; Forsblad, M.; Slovic, P.; Västfjäll, D. The Affect Heuristic and Risk Perception—Stability across Elicitation Methods and Individual Cognitive Abilities. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulianiti, K.P.; Havenith, G.; Flouris, A.D. Metabolic energy cost of workers in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, tourism, and transportation industries. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yovi, E.Y.; Yamada, Y. Addressing Occupational Ergonomics Issues in Indonesian Forestry: Laborers, Operators, or Equivalent Workers. Croat. J. For. Eng. 2019, 40, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovi, E.Y.; Prajawati, W. High risk posture on motor-manual short wood logging system in Acacia mangium plantation. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2015, 21, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, K. The role of traditional knowledge to frame understanding of migration as adaptation to the “slow disaster” of sea level rise in the South Pacific. In Identifying Emerging Issues in Disaster Risk Reduction, Migration, Climate Change and Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Schweiker, M.; Huebner, G.M.; Kingma, B.R.M.; Kramer, R.; Pallubinsky, H. Drivers of diversity in human thermal perception—A review for holistic comfort models. Temperature 2018, 5, 308–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimetz, E.; Kumar, S.; Mosler, H.-J. Effects of an awareness raising campaign on intention and behavioural determinants for handwashing. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitmer, D.E.; Sims, V.K. Fear Language in a Warning Is Beneficial to Risk Perception in Lower-Risk Situations. Hum. Factors 2021, 65, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, C.E.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Taylor, A.L.; Dessai, S.; Kovats, S.; Fischhoff, B. Heat protection behaviors and positive affect about heat during the 2013 heat wave in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hass, A.L.; Runkle, J.D.; Sugg, M.M. The driving influences of human perception to extreme heat: A scoping review. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yovi, E.Y.; Yamada, Y.; Zaini, M.; Kusumadewi, C.; Marisiana, L. Improving the OSH knowledge of Indonesian forestry workers by using safety game application: Tree felling supervisors and operators. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2016, 22, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Gross, J.J. Behavior change. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2020, 161, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forestry Workers | Paddy Farmers | ||

| Age | Mean = 44; SD = 11 | Mean = 50; SD = 13 | |

| Gender | Female | 27 | 118 |

| Male | 183 | 97 | |

| Education | Elementary school | 123 | 168 |

| Middle-high school | 85 | 47 | |

| College degree | 2 | 0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 34 | 94 |

| Married | 176 | 121 | |

| Work experience | Mean = 9; SD = 8 | Mean = 9; SD = 8 | |

| Work hour/day | Mean = 7; SD = 1 | Mean = 7; SD = 1 | |

| Latent Variable | Indicator Variable |

|---|---|

| Heat-related knowledge (K) | Symptoms (K2) |

| Prevention and first aid (K3) | |

| Work performance (K4) | |

| Risk perception | |

| Dread risk factor (DF) | Controllability (DF1) |

| Dread (DF2) Severity (DF3) | |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | Observability (UF1) |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | I start my workday early in the morning (PB1) |

| I collaborate with my coworkers to share work shifts (PB2) | |

| I have reduced my work hours while increasing the number of workdays (PB3) | |

| I have begun to involve more of my coworkers in our daily tasks (PB4) | |

| To avoid overheating, I take a short break whenever I feel hot (PB6) | |

| I wear work clothes made from materials that easily absorb sweat (PB7) | |

| I prefer wearing whole-body, layered clothing, and trousers for added protection (PB9) | |

| When it’s hot, I seek shade to stay cool (PB13) | |

| I have requested my boss to provide a first aid kit at the workplace (PB15) | |

| I have asked my boss to establish emergency protocols in case of emergency (PB16) |

| Variable | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF→PB | 0.387 | 0.393 | 0.037 | 10.544 | 0 | Significant |

| K→DF | 0.264 | 0.269 | 0.047 | 5.671 | 0 | Significant |

| K→PB | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.039 | 9.561 | 0 | Significant |

| K→UF | 0.031 | 0.03 | 0.048 | 0.641 | 0.522 | No Sig. |

| UF→PB | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.038 | 3.203 | 0.001 | Significant |

| Variable | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K→DF→PB | 0.102 | 0.105 | 0.019 | 5.281 | 0 | Significant |

| K→UF→PB | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.603 | 0.547 | No sig. |

| Moderation Variable | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (K→PB) | −0.028 | −0.031 | 0.051 | 0.544 | 0.587 |

| Gender (K→PB) | −0.025 | −0.014 | 0.051 | 0.495 | 0.621 |

| Occupational group (K→PB) | −0.112 | −0.103 | 0.051 | 2.194 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yovi, E.Y.; Nastiti, A.; Kuncahyo, B. Heat-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior among Indonesian Forestry Workers and Farmers: Implications for Occupational Health Promotion in the Face of Climate Change Impacts. Forests 2023, 14, 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071455

Yovi EY, Nastiti A, Kuncahyo B. Heat-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior among Indonesian Forestry Workers and Farmers: Implications for Occupational Health Promotion in the Face of Climate Change Impacts. Forests. 2023; 14(7):1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071455

Chicago/Turabian StyleYovi, Efi Yuliati, Anindrya Nastiti, and Budi Kuncahyo. 2023. "Heat-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior among Indonesian Forestry Workers and Farmers: Implications for Occupational Health Promotion in the Face of Climate Change Impacts" Forests 14, no. 7: 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071455

APA StyleYovi, E. Y., Nastiti, A., & Kuncahyo, B. (2023). Heat-Related Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior among Indonesian Forestry Workers and Farmers: Implications for Occupational Health Promotion in the Face of Climate Change Impacts. Forests, 14(7), 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071455