Abstract

Non-timber forest product plantations (NTFP plantations), also known as “economic forests” in China, refer to forest plantations cultivated for the production of non-timber products such as fruits, nuts, oils, seasonings, and medicinal materials. With a rapid increase in the total area in the past two decades, NTFP plantations have become an important type of forestland use in China. The shift of agricultural labor to the non-agricultural sector caused by rising salaries in China will inevitably have a great impact on land use, forestry, and agricultural production. To understand the effects of off-farm employment on the development of NTFP plantations in China, a total of 709 valid household questionnaires from Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces were collected. Heckman’s two-stage model was employed in the empirical analysis. The results of the study show that off-farm employment has a significant positive effect on both the probability that a household has planted NTFP plantations and the plantation area. Households engaged in off-farm employment would prefer to plant NTFP plantations. Moreover, the higher the degree of participation in off-farm employment, the more likely households are to choose to plant NTFP plantations. The area of NTFP plantations would increase with the increase in off-farm employment degrees. Besides, the age and education level of the household head show a positive effect on the NTFP plantation planting. The implication of the results is that with a continuing increase in the proportion of off-farm employment, NTFP plantation cultivation could also continue to expand. Funds are still an important constraint for households to choose to plant NTFP plantations. Therefore, if policymakers want to promote the development of NTFP plantations on collectively owned forestland, they should first resolve households’ financial constraints.

1. Introduction

The importance of non-timber forest products plantations (NTFP plantations) has been widely recognized [1,2]. It has developed rapidly over the past 50 years, especially in developing countries [3]. In China, non-timber forest product plantations (NTFP plantations), commonly known as “economic forests”, are considered one of the most important forest types for utilization. In the Forest Law of the People’s Republic of China (1998), NTFP plantations are defined as forest plantations cultivated for the production of various non-timber products, including fruits, nuts, oils, seasonings, industrial raw materials other than timber (e.g., natural rubber and resin), and medicinal products. The Chinese government has also attached great importance to the development of NTFP plantations. NTFP plantations are considered an important way to enhance rural households’ income. The General Office of the State Council of China issued “Opinions on accelerating NTFP plantations’ development” in 2012. In 2021, 10 ministries including the National Development and Reform Commission of China, the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Ministry of Finance of China issued Opinions on the scientific use of forestland resources to promote the high-quality development of woody grains, woody oils, and other NTFP plantations. Many provincial governments have also issued corresponding supporting policies to promote the development of NTFP plantations.

However, the development of NTFP plantations did not proceed as the government expected. According to the national forest inventory data from 1973 to 2013, the area and proportion of NTFP plantations and timber forests almost kept the same increasing rate in collective forest areas in southern China. The annual increase in the area of NTFP plantations and timer forests has also remained the same in recent years [4]. Therefore, why are the households not so enthusiastic about planting NTFP plantations even under the policy incentives? As pointed out by Mather [5] and other researchers, the change in forest type may be caused by accelerated urbanization and forest industrial policy [6,7]. However, as one of the important reasons, the effects of off-farm employment on NTFP plantations are seldom discussed. Off-farm income has been the largest source of income for rural households in China.

The wages in China have experienced rapid growth in the past few decades. According to the China Statistical Yearbook (Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China, see http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/, accessed on 20 November 2021), the real annual average wage in cities and towns increased from 5348 Chinese Yuan (CNY) (1 USD = 6.39 CNY as of 27 November 2021) in 1995 to 57,697 CNY in 2020 in China. In the past decades, the huge income gap between rural and urban regions attracted hundreds of millions of former agricultural workers to migrate to non-agricultural sectors. According to the 2020 Rural Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report (Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China; see http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202104/t20210430_1816933.html, accessed on 20 November 2021), the total number of rural migrant workers in 2020 was 285.6 million. The shift of agricultural labor to non-agricultural sectors will inevitably have a great impact on agricultural and forestry production. A few kinds of literature discuss the relationship between off-farm employment and NTFP plantation planting, but no consensus has been reached. Some existing research has revealed that rural households engaged in agricultural production may invest in higher-value crops upon receiving remittances from non-agricultural sources. A study by Frayer et al. [6] in Yunnan Province found that in the context of labor migration, farmers choose to plant higher-income NTFP on agricultural and forest land to adapt to the scarcity of family labor. Li et al. [8] also discovered that in the northwestern region of China, off-farm remittances from households are channeled into the cultivation of higher-valued apples as well as the engagement of labor for apple planting. Based on satellite data from 2004 to 2014, Su et al. [9] found that the area of the NTFP had been expanding around Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, in China. Moreover, most of them were planted on land that was originally timber forests. He et al. [10] found that off-farm employment promoted the development of NTFP plantations represented by fruit tree species based on survey data in Chongqing city. Coincidentally, a similar phenomenon has been observed in other countries. In Bolivia, Zimmerer [11] discovered that remittances have contributed to the transition from subsistence agriculture towards market-oriented fruit production. However, Dinh et al. [12] found that off-farm income has a significant negative effect on farmers’ planting activity on forest land. Cheng et al. [13] considered that rising labor costs decreased the ratio of NTFP plantations using a household survey panel dataset covering nine provinces in China. Nguyen et al. [14] conducted surveys of 400 households in three regions of central Vietnam. They discovered a negative correlation between the proportion of wage income and the development of NTFP plantations. Furthermore, after conducting theoretical deduction on the afforestation behavior of households with varying levels of non-agricultural employment, Zhang et al. [15] draw distinct inferences. It was determined that agricultural households not participating in non-agricultural employment tend to plant timber forests. Therefore, existing literature primarily explores factors such as household endowments, the characteristics of household heads, and forestry management that affect a single type of NTFP plantation cultivation. However, during the massive flow of labor away from farms in rural China, existing studies still lack specific attention on the impact of off-farm employment and fail to provide an analysis of rural households’ decision-making regarding NTFP plantation cultivation.

Thus, our question is: Which factors determine households’ NTFP plantation planting decisions? What is the relationship between off-farm employment and NTFP plantations on collectively owned forest land? More and more agricultural workers will continue to move to non-agricultural sectors due to rising wages. Therefore, clarifying the impact of off-farm employment on NTFP plantation planting decisions is very important for the government to achieve its NTFP plantation development goals. The aim of this paper is to analyze the effects of off-farm employment on NTFP plantation planting using questionnaire survey data.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Analysis

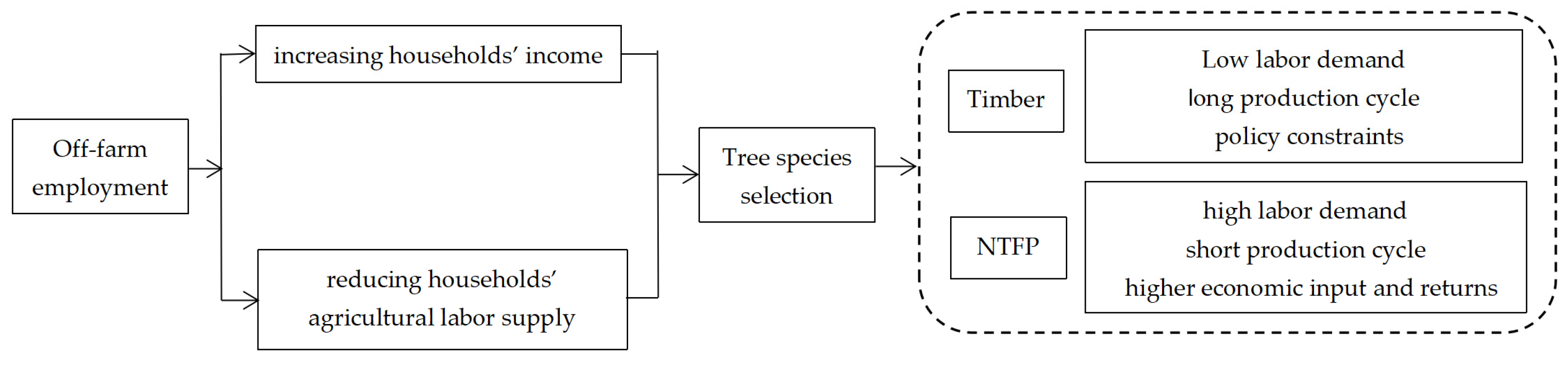

This paper is based on the “New Economics of Labor Migration” proposed by Stark and Bloom [16]. According to their theory, rural households aim to maximize their family’s utility by allocating their labor resources across various sectors. When farmers engage in off-farm employment, their household income experiences a rise while the supply of agricultural labor decreases, thus affecting the family’s choice of forest species. Specifically, when off-farm employment increases households’ income, it not only increases the ability of households to purchase capital and labor services but also improves their ability to bear agricultural production risks. Since the production of NTFP plantations is more sensitive to liquidity constraints, operating risks, and higher economic returns, income from off-farm employment may encourage household members who continue to engage in agricultural work at home to choose to manage NTFP plantations or expand the scale of NTFP plantations.

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of this paper. When off-farm employment decreases households’ agricultural labor, the substitution effect occurs in two aspects. When not considering forestland transfer behaviors, households could either take management factors substitution or tree species substitution. On the one hand, households can use forestry machinery to save labor in the form of management factor substitution. However, the potential of factor substitution is often limited. In fact, factor substitution on forest land is more difficult because of the slope of forestland, especially in China’s southern collective forest land. At the same time, households can also choose to plant tree species that require relatively less labor when facing labor constraints. It is common that the demand for labor in timber forests is significantly lower than that of NTFP plantations. However, timber forests generally have a long production cycle, thus increasing the management risks and payback period. Moreover, timber forest management faces more policy constraints in China, such as the logging quota policy.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of the impact of off-farm employment on rural households’ NTFP plantations.

In general, households will witness an augmentation in wage income after the labor migration, enabling them to increase their capital investment in NTFP plantation cultivation. On the other hand, off-farm employment may lead to a reduced input of labor in forestry. It is currently challenging to substitute manual labor with machinery in forestry cultivation. However, when rural households are making choices about forest species planting, they consider the restrictions imposed by policy constraints on timber harvesting and the long-term payback period of timber planting. Additionally, rural households also take into account the higher economic returns and shorter payback periods of NTFP plantations. Thus, in order to achieve maximum utility for the family, it is possible that after participating in off-farm employment, rural households may encourage family members to engage in the management of NTFP plantations or expand the scale of NTFP plantations.

Based on the above analysis, the research hypothesis of this article is proposed as the follows: off-farm employment will promote households’ decision to plant NTFP plantations and the planting area of NTFP plantations.

2.2. Data Collection

Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces are both located in the western part of China. Both of these two provinces are major centers of China’s rural labor migration. According to the 2019 Rural Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report, the population of rural migrant laborers from Shaanxi and Sichuan provinces was up to 7.667 million and 24.826 million, respectively, in 2019.

According to the Ninth National Forest Inventory Report, both forest area and planting area of NTFP plantations in these two provinces rank in the top ten in China. The total area of forest in Sichuan Province is 18.40 million hectares, and Shaanxi province’s forest area is 8.87 million hectares. Among them, the area of NTFP plantations in Sichuan Province was 1.10 million hectares, accounting for 6.0% of the total forest area. The planting area of NTFP plantations was 1.17 million hectares in Shaanxi province, accounting for about 13.2% (The data is available on http://forest.ckcest.cn/sd/si/zgslzy.html, accessed on 6 November 2021). Besides, both of these two provinces’ total area of NTFP plantations showed an increasing trend in the last 20 years. Therefore, Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces were selected as sample areas in this study.

According to different forest types and different geographic distributions and administrative levels, 46 villages distributed in 10 counties were chosen as our study area in Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces. Among them, seven counties are from Sichuan province and three are from Shaanxi province according to the size of the two provinces (the area of Shaanxi province is about 205,600 km2, and the area of Sichuan Province is about 486,000 km2). Stratified random sampling was used to select the towns and villages for the questionnaire survey based on the rural household per capita income of all towns and villages in each county. Two or three counties were first selected in each county. Then, all villages within each selected town were divided into high-income and low-income villages. We selected one village in each type, giving a total of two villages in each town. Finally, the sample households were obtained using a stratified random sampling procedure. In each village, 15–20 households were randomly selected for the survey.

With the assistance of the local communities, we conducted the questionnaire survey between June 2018 and April 2019. We collected information on households in 2017 through face-to-face interviews. To reduce data collection errors, all investigators received unified training before the investigation. The head of the household is our main interviewee. The household head’s spouse or another adult family member was interviewed in cases where the household head was not home during our investigation. The survey questionnaire primarily encompasses information on the off-farm employment status of sampled rural households, the forestry management situation, family endowment, and the characteristics of the household head. A total of 779 households were surveyed, and 779 questionnaires were collected. After the screening and elimination of invalid questionnaires, 709 valid observations were used in the analysis in this paper.

2.3. Specification of the Model

This study aimed to estimate the impacts of the households that participated in off-farm employment on NTFP plantation planting. According to Li et al. [17], NTFP plantation planting has no statistically significant effect on household migration decisions. Therefore, we do not consider the endogeneity arising from the reversed causality between NTFP plantation planting and off-farm employment. In practice, forest planting options are a combination of a two-step decision-making process. The first step is to decide whether to plant NTFP plantations or not. The second step is to make decisions on the area to be planted. Because some unobserved factors may affect households’ choice of NTFP plantation planting behavior and their decision to plant NTFP plantations and adjust the share of NTFP plantations at the same time, the problem of sample selection bias arises and the obtained parameters will be biased. Therefore, Heckman’s two-stage model was employed.

The first stage of the model is a typical Probit model of whether households have planted NTFP, and then the inverse Mills ratio is estimated. At this stage, the inverse Mills ratio is obtained as follows:

In Formula (1), Pi is a binary variable that shows whether a household decided to participate in NTFP planting. Pi = 1 if the household chooses to plant NTFP plantations; if not, Pi = 0. Here, Ii is the core variable, which shows whether households have participated in off-farm work. Xi is a set of control variables, and εi shows the term of error.

In the second stage, the effects of households’ off-farm activities on the NTFP plantation planting area were estimated by the maximum likelihood method. Sample selection bias is corrected using the inverse Mills ratio obtained from the first stage. The OLS regression model at this stage is as follows:

In Formula (2), Yi shows the planting areas of NTFP plantations. Ii refers to whether households have participated in off-farm work. Xi is a set of control variables that influence NTFP plantation selection decisions, is the inverse Mills ratio, and εi shows the term of error.

Rural labor migration includes two basic forms: industrial migration and geographical migration [18]. In this paper, an “off-farm employment household” is defined as a situation when one or more household members are employed outside their county. Therefore, off-farm employment (Ii) is a binary variable [19]. In order to make sure that the estimated results are robust, we also used the proportion of off-farm income to measure the extent of households’ off-farm employment [20]. A higher share of household income from off-farm employment indicates a higher level of off-farm employment for the household.

Additionally, there are a range of other factors that may have effects on decision-making in forest species selection, including the characteristics of household heads and family members, forestland features, and other environmental factors.

The characteristics of the household head, the age, the level of education, and whether or not the household member has experience as a village leader all have impacts on the choice of forest species [21]. We assume that older household heads have more experience in planting NTFP plantations, and a household head who has received a higher education tends to adopt more advanced production technology. Furthermore, if the household member has experience of being a village leader, he or she could have a better understanding of relevant policies. As NTFP plantation planting needs more experience and skills, more advanced technology, and is more easily affected by the policy, household heads who meet these characteristics are more likely to plant NTFP plantations.

Regarding the characteristics of the family, the scale of the family’s labor force is strongly and positively correlated with the input of the labor force in NTFP plantation cultivation [22]. The total income of the family also influences the planting structure [20]. Total household income could be a reflection of the risk-taking of households. Therefore, a household with a higher total income can afford a larger investment in growing NTFP plantations.

Forestland features such as areas of total forestland, number of plots, and slopes can also have an impact on the choice of forest species [23]. The larger area of forest land implies a greater potential for a household to plant cash forest. The number of land plots indicates the fragmentation of land [24]. Scattered lands have a negative effect on labor-intensive NTFP plantation planting. Besides, households tend to increase their timber forest inputs in flat woodland [22], and the steeper slope of the woodland may exert a negative influence on the increase in NTFP inputs. In our investigation, the value of slope represents the forest owner’s subjective judgment on the slope of each piece of forestland. We averaged the slope value for households on all the forestland plots. The distance to markets may imply lower labor costs, thus decreasing the cost of planting NTFP plantations. Table 1 presents the definitions and summary statistics of the variables used in the estimation of model (2).

Table 1.

Definition and description of variables (N = 709).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information of Off-Farm Employment and Household Planting Selection

According to Table 1, about 43.7% of the households have participated in off-farm employment, and 46.3% of households have only participated in agricultural and forestry production. Furthermore, the average total forestland area of the investigated households was approximately 84.565 Mu. In our sample, about 45.3% of the households planted NTFP plantations. On average, cash forest plantations account for about 26.9% of the total forestland area.

Table 2 illustrates the differences between the two types of households in the forest plantations. The average scale of forestland was larger for those who were only engaged in agriculture and forestry. The average area of forestland owned by households that have participated in off-farm employment was 18.39 Mu less. It shows the same situation both in Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces. The difference in forestland area in Shaanxi province is small, while it shows a big difference in Sichuan province (24.79 Mu). When it comes to the forest species decision, off-farm employment households are more likely to plant NTFP. Table 2 shows that nearly half of the households involved in off-farm employment planted NTFP. The ratio is even higher in Shaanxi province, where 66.1% of the households involved in off-farm employment planted NTFP. Table 2 also shows that the average area and the proportion of NTFP plantation planting area were also larger for households that are engaged in off-farm employment. The average area of NTFP plantations was 18.51 mu. The proportion of NTFP plantation planting area was about 27.8%, which was 5.8% higher than households that only engaged in agriculture and forestry. Table 2 also shows that the difference in the average area and the proportion of NTFP between households engaged in off-farm employment and those only engaged in farm work in Shaanxi province is higher than that in Sichuan province.

Table 2.

Off-farm employment and household planting behavior.

3.2. Levels of Off-Farm Employment and NTFP Plantations

To better understand the relationship between off-farm employment and NTFP plantation planting behavior, the extent of off-farm employment income was used. We divided households engaged in off-farm employment into three equal groups according to their off-farm employment income ratio. We further analyzed the difference in households’ forest plantation behavior between different levels of off-farm employment (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, households with a medium level of off-farm income possessed the largest area of forestland (88.47 Mu) and NTFP plantation planting area (28.05 Mu). This may be due to the management characteristics of the NTFP. When the area of NTFP plantations reaches a certain scale, the demand for labor and funds would be higher. It is hard to manage the NTFP plantations just by relying on the households’ surplus labor. Moreover, the benefits of large-scale management of NTFP plantations may even be higher than the off-farm income. Therefore, households would choose to allocate all family labor to the management of NTFP plantations.

Table 3.

Levels of off-farm employment and NTFP plantation planting (N = 400).

In the case of the NTFP plantations planting decision, with the increase in the proportion of off-farm income, both the probability of households choosing to plant NTFP plantations (52.4% for the high-level group) and the proportion of the area planted with NTFP plantations (28.1% for the high-level group) increased. It also means that the motivation for NTFP plantation planting improved when households increased their income through off-farm jobs.

3.3. The Impacts of Off-Farm Employment on Households’ NTFP Plantation Choice

Table 4 presents the estimation results of the Heckman two-stage model and the model describing the effect of different variables on the area of NTFP plantation planting. The coefficient of the inverse Mills ratio is statistically significant at the 1% level. It could be considered that there was selection bias in the sample, according to these statistical results. Therefore, the obtained results estimated from the Heckman two-stage model are reliable.

Table 4.

The impacts of off-farm employment on households’ NTFP plantation planting.

The coefficient of households’ participation in off-farm employment is positive and significant at 5% and 1% levels separately in step 1 and step 2, which illustrates that off-farm employment of households has a significant impact on both the likelihood and the scale of investing in cash forest plantations. The results suggest that households engaged in off-farm work prefer to plant NTFP plantations and do so on a larger share of their forestland than households that do not engage in off-farm work. It means that households tend to enhance NTFP plantation planting areas when they engage in off-farm employment. The results are in accordance with the findings of Reardon et al. [25] and Frayer et al. [6]. This finding is also consistent with the theoretical analysis. On the background of off-farm employment, the judgment of grain plantation tendency was made based on the substitution effect. From the perspective of households, replacing laborers with machinery can offset the negative influence of labor constraints [26,27,28,29]. Compared to the cash crop, the grain plantation is better suited to mechanical production. Hence, it is favorable to achieve scale-up grain production through machinery substitution [27,28,30]. Although, in the field of forestry production, the cultivation of timber forests requires less labor input, it often takes a longer time to yield a return on investment. While NTFP plantation planting requires more capital and labor investment, it has a shorter return cycle and higher returns. Rural households that do not engage in off-farm employment have sufficient agricultural labor, but they have limited sources of income, resulting in strong financial constraints and weak risk resistance, leading them to be less inclined to choose NTFP plantation planting [15]. However, when the household budget constraint is alleviated, inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides increase. This can encourage them to pursue more profits and improve their ability to bear the risks of NTFP plantation planting. In addition, labor costs in China have been continuously rising in recent years, accelerating the off-farm transfer of rural households and increasing the labor costs of forestry operations. Therefore, rural households may choose relatively higher-income forest types under higher labor production costs, thus increasing overall household income [13]. Moreover, when farmers initially engage in non-agricultural employment, there is no significant labor constraint effect on household agricultural production, and under the condition of sufficient agricultural labor in the household, in order to further expand household income, farmers may adjust their planting structure towards labor-intensive but relatively high-value cash crops [31]. Therefore, the conclusions drawn from the observations of Chinese data in this article differ from those of Nguyen et al.’s [14] study in Vietnam.

In addition, we also did a robust test using the ratio of off-farm income (Table 5). The results of the robust test reveal that the signs and significance levels of the altered explanatory variables remain largely consistent with the benchmark equation in Table 4, thereby ensuring the robustness of the findings.

Table 5.

The results of robust test.

3.4. Effect of Other Factors

Control variables, including the characteristics of the household head and family, the forestland features, and external environmental factors, all have an impact on households’ decision-making regarding NTFP plantation cultivation.

From the point of view of the characteristics of the household head, according to the empirical results (Table 4), the effects of both the age and the education level of the household head are positive and statistically significant at a 1% level. It suggests that when the head of a household is older and more educated, the household would not only prefer to plant NTFP plantations but also tend to have a higher proportion of cash forest planting area. These results are in accordance with our expectations, as stated above. Regarding other household characteristics, the results indicate that the family labor force negatively affects the ratio of cash forest area to total forest area. Households with a large labor force may be more inclined to engage in off-farm work, thus reducing the number of households engaged in agricultural activities.

Total forest land area shows a positive and significant effect on NTFP plantation planting behavior. It means that households owning larger forestland would prefer to plant NTFP plantations. Besides, when the number of forest plots is larger, the proportion of cash forest planting area is smaller. Fragment of forestland would increase the cost of input, thus discouraging households from expanding NTFP plantation cultivation. Furthermore, the slope is negatively correlated with the proportion of cash forest plantation area at a 5% significance level. Normally, it is more difficult to plant NTFP plantations on steeper land.

The distance from the market as a variable of external environmental factors is positive and significant in the second stage. It means households living far away from the market would plant a larger area of cash forest. This may be due to the fact that there are fewer off-farm employment opportunities for labor in areas far from towns, thus leading to lower labor prices. The lower labor cost reduces the cost of planting NTFP plantations, thus encouraging them to plant cash forests.

4. Conclusions

Rapidly rising wages have led to the transfer of a large number of rural laborers to non-agricultural sectors, affecting the management of agriculture and forestry in China. What impact does off-farm employment have on farmers’ choice of planting NTFP plantations? To answer this question, a questionnaire survey was conducted in Sichuan and Shaanxi provinces. A total of 709 valid questionnaires were empirically analyzed using a regression model.

The results show that 43.7% of the respondents have participated in off-farm employment, and about 45.3% have planted NTFP plantations. Of the households that have participated in off-farm employment, 48% have planted NTFP plantations, which is more than the households that have not engaged in off-farm employment. Additionally, the difference is even much bigger in Shaanxi province. Moreover, the average area of NTFP plantations they planted is also larger than the rural households that have not engaged in off-farm employment. Further, we found that the higher the proportion of off-farm employment income, the higher the proportion of participants in planting NTFP plantations. However, the planting area of NTFP plantations decreased when the proportion of off-farm employment income reached a high level in our analysis. We use the Heckman two-stage model to verify the effects of off-farm employment on NTFP plantation planting behavior. Results show that off-farm employment has a significant positive effect on both planting activity and the planting area. The age and education level of the households show a positive effect on the planting activity and planting area. According to the results of descriptive statistical analysis and regression analysis, we come to the following conclusions:

First, off-farm employment has promoted the household’s NTFP plantation planting behavior. Both our descriptive statistical analysis and regression analysis proved that households engaged in off-farm employment would prefer to plant NTFP plantations. Moreover, the higher the degree of participation in off-farm employment, the more likely households would choose to plant NTFP plantations. The implication of our research is that funds are still an important constraint for households to choose to plant NTFP plantations. Moreover, with the further increase in the proportion of off-farm employment because of rising wages, it is predictable that the area of NTFP plantations will further increase.

Second, the area of NTFP plantations will increase with the increase in off-farm employment degrees, but this increased level may have a certain limit. The descriptive statistical analysis shows that when the planted area or proportion of NTFP plantations reaches a certain level, the planted area of NTFP plantations declines. The implication of this result is that the management of large-scale NTFP plantations does not come from households who are both engaged in on-farm and off-farm employment. In addition, due to restrictions on the use of forestry machinery, it is difficult for rural households with high levels of off-farm employment to invest more labor in planting NTFP plantations. Moreover, the purpose of planting NTFP plantations for most of the households who engaged in off-farm employment is to obtain more sources of income, not to make a living by planting NTFP plantations. Therefore, with other conditions unchanged, as the degree of off-farm employment deepens for most rural households, the area of NTFP plantations may decrease in the long run.

Therefore, if policymakers want to promote the development of NTFP plantations on southern collectively owned forest land, they should resolve households’ financial constraints first. The policymakers ought to issue and refine policies for interest-free loans specifically tailored to the cultivation of NTFP plantations. Additionally, to address the labor constraints caused by the high-level off-farm employment of rural households, it is essential to augment research and development investment in forestry machinery for NTFP plantation planting, particularly to overcome the topographical limitations.

Due to the relatively short observational period of the data, there are certain limitations to this study. Consequently, in the future, it would be beneficial to extend the observation period for micro-farmers’ planting decisions in order to enhance the accuracy of estimation. Furthermore, there is potential for conducting further research to delve into the mechanisms by which off-farm employment influences the cultivation of NTFP plantations. This avenue of study could involve empirical analyses aimed at uncovering the impact of forestry machinery on labor substitution as well as assessing the contribution of non-agricultural income.

Author Contributions

W.Z. contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by J.-Y.D., Z.-Q.Z., W.Z. and P.-Y.T. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.-Y.D. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Fund of China under Grant 72003069, National Natural Science Fund of China—Major International (Regional) Joint Research Project under Grant 71761147003, Humanities and Social Science Research West Project of the Ministry of Education, China under Grant 21XJC790015.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, S.L.; Xu, J.T. Livelihood mushroomed: Examining household level impacts of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) under new management regime in China’s state forests. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 98, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Steur, G.; Verburg, R.W.; Wassen, M.J.; Teunissen, P.A.; Verweij, P.A. Exploring relationships between abundance of non-timber forest product species and tropical forest plant diversity. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, W.W.; Yu, Y.; Tang, R.C.; Guo, X.M.; Wang, B.; Yang, B.; Zhang, L. How much will cash forest encroachment in rainforests cost? A case from valuation to payment for ecosystem services in China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 38, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zinda, J.A.; Ke, S. Designating tree crops as forest: Land competition and livelihood effects mediate tree crops impact on natural forest cover in south China. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. The forest transition. Area 1992, 24, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Frayer, J.; Sun, Z.L.; Müller, D.; Munroe, D.K.; Xu, J.C. Analyzing the drivers of tree planting in Yunnan, China, with Bayesian networks. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, D.J. The influence of agricultural industrial policy on non-grain production of cultivated land: A case study of the “one village, one product” strategy implemented in Guanzhong Plain of China. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Wang, C.G.; Segarra, E.; Nan, Z.B. Migration, remittances, and agriculturoal productivity in small farming systems in Northwest China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.L.; Zhou, X.C.; Wan, C.; Li, Y.K.; Kong, W.H. Land use changes to cash crop plantations: Crop types, multilevel determinants and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.F.; Yan, J.Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.B. The micro-mechanism of forest transition: A case study in the mountainous areas of Chongqing. J. Natl. Resour. 2016, 31, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerer, K. The compatibility of agricultural intensifification in a global hotspot of smallholder agrobiodiversity (Bolivia). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2769–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, H.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hoang, V.; Wilson, C. Economic incentive and factors affecting tree planting of rural households: Evidence from the Central Highlands of Vietnam. J. For. Econ. 2017, 29, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.Q.; Zhang, H. The Structure of Commercial Forests“Tending to Become Economic Forests”: An Analysis of Causes Based on Labor Cost Effects and Relative-Revenue Effects. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Lv, J.H.; Vu, T.T.H.; Zhang, B. Determinants of Non-Timber Forest Product Planting, Development, and Trading: Case Study in Central Vietnam. Forests 2020, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Incentive effectiveness of compensation of sloping–Land Conversion Program--from the perspective of heterogeneous farmers. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 2, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D. The New Economics of Labor Migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Gan, C.; Ma, W.L.; Jiang, W. Impact of cash crop cultivation on household income and migration decisions: Evidence from low-income regions in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2571–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.L.; Li, X.Y.; Yuan, M.Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, C.; Luo, B.X. Differences between farmers’ perception and behavior decisions on crop planting: An empirical study of Jianghan Plain. Res. Agric. Mod. 2016, 37, 892–901. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.Z. The impacts of labor migration on farm households’ cropping structure. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Q.G.; Wang, Q.Z.; Zhu, X.L.; Zhou, H. Migration, Revenue Growth & Crop Structure Adjustment: Based on Farmers Household Survey Data of Jiangsu Province. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2014, 14, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Shen, Y.Q.; Zhu, Z.; Ning, K.; Qiu, F.M. Analysis on Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Willingness to Expand the Scale and the Scale of Economic Forest Planting—Taking Zhejiang province as an example. Issues For. Econ. 2016, 36, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, X.L.; Wu, W.G. The Influence of the Stability of Forestland Property Right on the Farmers’ Afforestation Investment. For. Resour. Wanagement 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Mi, F. Influencing factors of farmers’ willingness to construct bio-energy forest: Taking jianning county, fujian province as an example. J. Beijing For. Univ. (Soc. Sci) 2014, 13, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Liu, J.J.; Chen, F.L. Impact of Farmland Fragmentation on Structure of Grain Crops: A Microcosmic Analysis Based on Rural Fixed Observation Point. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2018, 17, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.A.; Crawford, E.W.; Kelly, V. Links Between Nonfarm Income and Farm Investment in African Households: Adding the Capital Market Perspective. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1994, 76, 1172–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H. The transfer of labor force and food security. Stat. Res. 2014, 31, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.W.; Zhang, M. Contribution of Agricultural Mechanization to Grain Production under Agricultural Labors Migration. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2014, 13, 595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.B.; Ru, G.; Qin, Y. Labor Migration, Technological Progress and Grain Production. J. Nanjing Audit Univ. 2017, 14, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Yi, F.J.; Yu, X.H. Rising cost of labor and transformations in grain production in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.P.; Hong, W.J.; Luo, B.L. The transfer effect of agricultural labor force and grain-oriented planting structure. Reform 2019, 7, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, T.W.; Luo, B.L. What leads to a “Tendency to plant grains” in agricultural planting structure? An empirical analysis based on the impact factors of land property rights and factors allocation. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 2, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).