1. Introduction

Charcoal is an important energy source across Africa, and the continent accounts for 65% of its global production [

1,

2]. Since charcoal contains approximately 1.7 times more energy than firewood per unit weight, it is suitable for long-distance trade [

1,

3]; hence, the charcoal trade can be observed from production sites in forested regions to places where markets can be found.

Aspects of charcoal production, commerce, and significance for livelihoods in Africa have been analyzed in previous studies [

4,

5]; however, the charcoal trade in the western Sahel region (Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) is not so adequately described. This part of Africa, characterized by low rainfall and with a considerable population of 90 million, is highly dependent on biomass for household energy needs. This biomass includes, to an important degree, charcoal, and the consumption of this energy carrier in the region is on the rise (p. 82, [

1,

6]). Ouedraogo [

7] documented that a section of the more well-off households in Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso frequently used charcoal alongside fuelwood for energy; however, the study did not trace the origin of the charcoal quantities. The charcoal trade from the north of Ghana, a West African country, to the demand centers in the southern region of the country has been studied [

8,

9]. Moreover, the importance of the charcoal trade in Africa, including the Sahel, has been examined and described by Nyarko et al. [

10]. Despite previous studies, detailed information about product flows and involved actors in the Sahel is still in part lacking.

Charcoal production and trade across Africa mainly operate in the informal sector; therefore, the business practices and actors involved are not well documented in official reports and statistics [

1,

11]. Nonetheless, business strategies among producers have been published in individual studies from the Democratic Republic of Congo [

4], Uganda [

12], Kenya [

13,

14], Malawi [

15,

16], and Ghana [

8,

9]. These studies generally characterize the charcoal sector as having low entry barriers with thin profit margins, even though the research distinguishes a few powerful large-scale market players [

5,

14,

17]. According to Ihalainen et al. [

18], women are more frequently engaged in retailing than in production and transport, and they generally capture smaller benefits than their male colleagues.

Another area of research has focused on the sector’s sustainability implications, including its impact on livelihoods and forest conditions [

14,

19,

20,

21]. This literature suggests that the charcoal sector can trigger forest degradation and deforestation that impacts carbon flow and biodiversity, with consequences for the sustainable development goals (SDGs) 13 (climate action) and 15 (life on land). Conversely, the charcoal sector benefits low-income households and indirectly affects poverty, food security, and schooling by providing means to cover school fees, consequently supporting SDGs 1 (no poverty), 2 (no hunger), and 4 (quality education).

The extant literature suggests policy interventions to improve the sustainability of the charcoal sector, including mobilization of charcoal producers for sustainable practices, development of more efficient production, formalizations of the sector, and community participation [

1,

11]. However, further improvements in the charcoal sector in the Sahel are hampered by knowledge gaps concerning traders both at the wholesale and retail stages. Insights about value streams, business practices, resource use, and marketing strategies are crucial for policies aiming to improve the sector’s long-term viability. Together with insights into charcoal production, knowledge of the trade at both the wholesale and retail levels would enable the development of regulatory and trade policies and inclusive actions to improve the sector’s contribution to livelihoods and sustainable development. Otherwise, less appropriate practices and regulations risk leading to wasteful and unsustainable production and use [

1,

2,

22]. Therefore, this study had three research objectives:

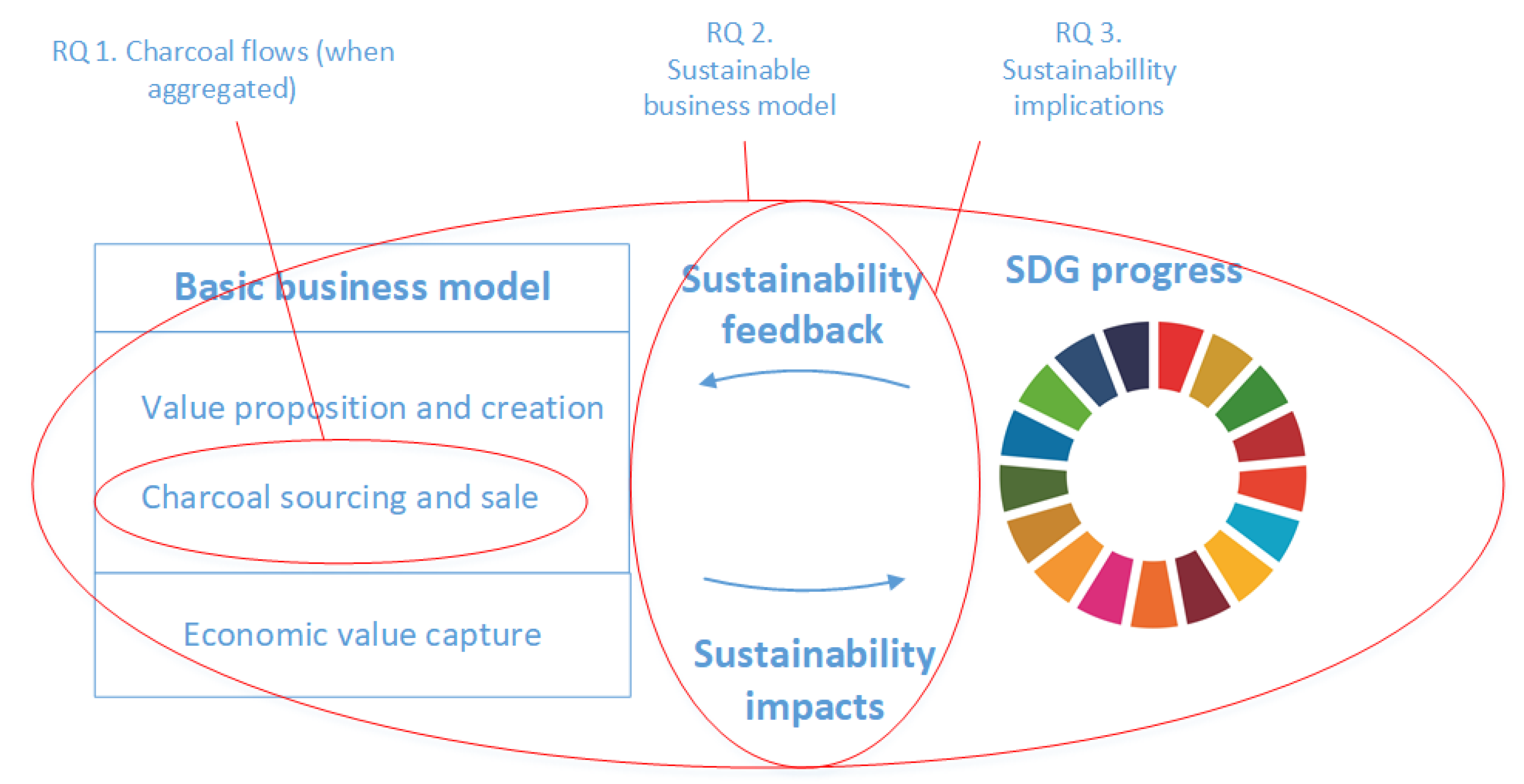

Analyze the product flows of the charcoal trade in southern Niger.

Characterize the charcoal traders’ business model and their strategic considerations.

Indicate key sustainability implications of charcoal trade regarding livelihoods and the environment.

The subsequent section presents the methods applied in this study, including the conceptual framework and the research approach. The results section describes the findings and subsequently a discussion of their implications. The final section presents this study’s conclusions.

3. Results

3.1. The Sample

In total, 347 interviews were conducted at five locations (

Table 1 above). Information about the profile of the weighted sample is listed in

Table 2.

Table 2 provides a sample overview based on weighted values.

Most respondents were male. The female representation was the lowest in Maradi (4.7%) and Niamey (11.8%) and the highest in Gaya (28.6%) and Dosso (22.2%).

A large share were small retail traders, whereas a minority handled larger wholesale quantities. The age of the traders varied, with an average age of 40.8 years, indicating that the charcoal trade is not an occupation for youth. Most interviewees perceived the charcoal trade as part-time, combined with the trade of other goods, e.g., food items. One-fifth of the respondents answered that the charcoal trade was their main occupation (highest in Maradi with 26.7%, and lowest in Gaya with 15.8%). Thus, in most cases, the charcoal trade was combined with commerce in other items, restaurants, or other businesses. Only a few respondents combined trading charcoal with farming or other salaried employment.

3.2. Trade Flows

The results also revealed that over 73.6% of the charcoal was imported. Nigeria is the primary source of charcoal, whereas Burkina Faso and Benin serve markets that are situated closest to the respective country borders (

Table 3 and

Figure 5). Domestic production accounted for less than a third of the charcoal that retailers sold.

The weighted quantities indicate that the five cities source most of their charcoal from Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and domestically. Niamey features diverse supply sources, where substantial quantities are bought from Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Niger, whereas Maradi and Konni are more dependent on Nigeria for charcoal. Benin supplies some proportion of the consumption in Dosso and Gaya. However, these quantities represent small shares of the total consumption. This study shows that if the total sourcing shares are similar to the country totals [

3], the total import quantities would consist of 354,348 tons from Nigeria, 186,052 tons from Burkina Faso, 11,580 tons from Benin, and 219,248 tons from Niger [

3].

Table 4 lists key figures about the countries supplying charcoal to Niger. The group of countries faces similar challenges to meet the needs of growing populations and to protect the environment.

Niger and its neighbors have growing populations, potentially creating an increasing demand for forest products in the region, specifically for wood energy (

Table 4). All four countries also recorded a decreasing forest area between 2010 and 2020. Furthermore, poverty rates are also high. These challenges indicate difficulties in the four countries in meeting the Agenda 2030 goals regarding life on land and no poverty [

34].

The traded quantities for the three categories are shown in

Table 5.

The overall high share of small-scale traders selling less than 20 bags per month reflects the normal distribution situation in emerging economies where consumers do not have transport availability to frequent larger retailing centers (p. 117, [

35]).

Table 6 lists the traded quantities divided into supplier categories used by different trader types.

Small- and medium-scale producers purchased most of their charcoal from upstream traders/wholesalers. The distribution of sourcing quantities was similar between small and large retailers. Notably, a share of large producers (12%) sourced directly, possibly allowing them to integrate vertically and negotiate better prices.

3.3. Business Model

3.3.1. Value Proposition

The key component of the business model contains a value proposition comprising the charcoal product, customer groups, and customer relations. The most valued product quality dimensions reported for the respondents’ customers are listed in

Table 7.

Price and product quality were the most critical aspects of customer satisfaction reported by all types of charcoal traders. Both charcoal quality and quality tree species were highly rated. Price and the quality of packaging received slightly lower scores among the traders; however, these aspects were still seen as essential prerequisites for customer satisfaction.

The service aspects (availability, courtesy, credibility, and home delivery) were given slightly lower ratings than the product quality attributes, even though they are important components in the overall product–service value proposition (

Table 7). Service indicators were more highly rated among wholesale traders than small-scale traders, which reflects a more professional view of customer satisfaction in this group.

The key customer groups for the different size groups are indicated in

Table 8.

Small-scale traders mostly sold their charcoal to households. Large-scale traders sold relatively smaller, although still considerable, shares to households and more to large commercial customers. The specifically mentioned customer groups were tea sellers, tailors, and laundry operators (blachisseurs). Wholesale traders focused on retailers. However, several traders did not highlight a specific dominant target customer group.

3.3.2. Value Creation and Delivery

Value creation and delivery involve the key activities associated with buying and selling charcoal: skills, resources used, channels, and business partners (

Figure 1). The majority of the traders’ time (their activities) was used for selling activities, followed by purchasing, information processing (particularly among large-scale traders), and loading/unloading. The most traded tree species for the traders’ customers in the order of mention are listed in

Table 9. The raw material consisted of wood species, whereas alternative charcoal sources, e.g., agricultural waste, were not mentioned.

Furthermore, the additional physical resources reported included vehicles such as pickups and motorbikes. The findings revealed that 20% of the respondents owned a vehicle and 20% owned a motorbike; moreover, it was also common to rent a car or motorbike for charcoal transport. Other transport means included bicycles and carts pulled by donkeys or oxen.

The capabilities and competencies used in the charcoal business are listed in

Table 10.

The top three capabilities included physical strength to carry bags, good customer relations, market knowledge, and schooling knowledge. Wholesalers differed slightly from the larger sample and prioritized market and price knowledge, negotiation skills, and good customer relations. Partners in the charcoal business are listed in

Table 11.

Family plays a central role in charcoal-trading activities, and half the respondents across the different groups conducted trade together with family members (

Table 11). Traders also created partnerships with friends. However, the role of traders’ associations appeared insignificant, according to interview data. A few large-scale enterprises reported a high number of employees.

3.3.3. Value Capture

Value capture concerns earning revenues from the charcoal value proposition, associated value creation, and delivery. Economic estimates are listed in

Table 12.

The value capture values were converted from CFA francs to USD according to the exchange rate in November 2019.

Both the average purchasing and selling prices were lower among wholesalers compared with the categories focusing on retail. This difference may depend on the economies of scale and a fixed cost component in purchasing (e.g., fixed ordering costs). The circumstance can also explain why wholesale traders purchase more upstream in the supply chain, even from the producer, with lower unit prices. Wholesale traders may also have the market power to negotiate quantity discounts, indicating that wholesale traders obtained profits through a high asset turnover and by extracting a good unit margin. Small-scale traders could benefit from a larger gross margin per bag by charging high consumer prices. Large traders that served end-use customers obtained the lowest gross margins per bag. Small-scale retailers also reported the longest period between purchasing and selling charcoal. This cash-to-cash measure negatively affected returns on assets [

36].

Income from the charcoal trade was primarily used for food. Other cost items involved housing, school fees, medical costs, and helping extended families (

Table 13).

The findings indicate that trade may contribute to reducing poverty among poorer traders (43% were calculated to be below the assessed poverty line). Moreover, this rate coincides with the overall poverty rate for Niger of 45.4% [

29].

Alternative activities that could be performed in case charcoal income were to end are listed in

Table 14.

Table 14 indicates that traders would utilize diverse strategies if the charcoal trade disappeared, e.g., if the charcoal trade became banned for conservation reasons. Continued trade of other types of products was most frequently mentioned, alongside farming and transport. A higher percentage of wholesalers confirmed that emigration was a likely strategy. Wholesalers may have more possibilities than small-scale retailers to access the necessary financial means to emigrate.

3.3.4. Strategy

The traders’ expectations for the future were mixed (

Table 15). Nearly half of the respondents expected a reduced supply of charcoal; however, an increase in charcoal supply was also expected, particularly among wholesalers.

According to most categories, prices were expected to continue to increase, although the view within the wholesaler group was mixed. However, diverse views were expressed on the future general development of the charcoal sector. Large-scale traders and wholesalers showed a more optimistic view of the development of the sector than small-scale retailers.

3.3.5. Female Traders

The share of women among the respondents was less than 15%. Compared with men, women were mainly small-scale traders, and their gross margins were on average 20% of what men earned. Women had a more pessimistic view of the market, and they expected that the supply of charcoal would not increase. Moreover, they mostly thought the trade prospects were bleak.

The general view on women’s capacity to engage in the charcoal trade also differed between genders (

Table 16).

Men considered this capacity to be lower and cited reasons why women could not participate in the charcoal trade, which included security reasons, traditional norms, women’s lack of endurance or marketing skills, and the view that commerce was men’s work. Women, on the other hand, claimed that they were fully capable of participating in the charcoal trading business. One main obstacle for women to enter the charcoal business, mentioned by both genders, was household chores.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

The survey used in this study obtained new insights into the stated research questions. The charcoal trade in Niger is conducted by a range of actors, from large- to small-scale levels. The business sector includes a few large-scale actors and a high number of small-scale retailers. More than 70% of the charcoal comes from sources outside Niger, and nearly half the quantity is produced in Nigeria; however, charcoal also enters Niger from Burkina Faso and Benin (RQ1). Many traders combine charcoal in a portfolio of traded products, and business models differ between the different categories of traders. A common key ambition is to offer charcoal of high quality from preferred tree species. Large traders obtain revenues from the sale of large quantities and by sourcing at low prices, sometimes directly from producers. Small-scale traders/retailers benefit economically from higher consumer prices. Large retailers reach more modest unit margins. Respondents expect a reduced supply of charcoal, increasing prices, and, for their own business, stable or, for wholesalers, improved opportunities (RQ2). The activity contributes to sustainable development by generating additional income for the actors, which in some cases reduces their poverty level. However, the increasing import of charcoal from countries with weak forest governance and forest decline suggests that the value chains in their current unregulated form are not sustainable in the long term (RQ3).

This study confirms previous surveys documenting thriving charcoal use in West Africa [

7]. Additionally, our findings reveal a cross-border trade and expectations of increased charcoal quantities in the future. This study confirms earlier reports [

8,

10] that charcoal quantities are transported from forested areas, such as Nigeria, overland to less forested regions in Africa, such as the Sahel. Furthermore, this study’s results conform with study findings from the Democratic Republic of Congo and other parts of Africa, which describe how charcoal is usually transported to urban centers [

4].

The large imports of charcoal and comparatively modest domestic production in Niger are noticeable but not unexpected. However, the findings from the five studied cities in Niger do not conform to the 2019 data provided in the FAO databases [

3], which reported an annual production within the country of 771,843 metric tons and insignificant import quantities. The current study indicates a larger dependency on imported charcoal in Niger.

The high diversity in size classes of charcoal traders explains how the distribution and retailing of charcoal are organized in Niger and other low-income countries with similar characteristics. Low-income countries commonly show a fine network of small-scale retailers, partially because customers need local selling points and do not have the means to travel far to buy charcoal. In contrast, sourcing, transportation, and complicated cross-border trade bring advantages and economies of scale for a few large-scale resourceful actors. Large trade operators also appear to have a more professional approach to the charcoal trade than small-scale traders.

The presence of wholesale, large-scale, and small-scale traders agrees with the findings of Shively et al. [

17] in Uganda and Baumert et al. [

5] in Mozambique, which also indicated different size classes within the charcoal supply chains. This also reflects that charcoal revenues are proportional to the scale of operation; however, a strict categorization of charcoal traders may be too simplistic; large-scale traders may also sell to final customers and, conversely, individual small- or medium-scale retail traders can also source charcoal directly from producers.

The low participation of women in the charcoal trade, including small-scale retail, does not conform with some studies that document a high share of women in charcoal retail [

14,

18], although the situation in Niger may be explained by gendered conventions whereby trade is seen as a men’s occupation. However, the responses from female respondents demonstrate their preparedness to participate in the charcoal business.

Our findings confirm the previous results from Smith et al. [

16], which state that the charcoal sector plays a key role in livelihood diversification. The unequal distribution of revenues from the charcoal trade observed in the present study concurs with Shively et al. [

17] and Baumert et al. [

5].

4.2. Implications

This study further elucidates the trade flows and business aspects of charcoal in southern Niger including the supply situation, business practices, and prospects. A fair understanding of the charcoal trade in these cities may improve the possibilities for policy intervention.

The findings indicate improvement opportunities for better efficiency, customer satisfaction, and sustainability, highlighting the importance of charcoal quality for customer satisfaction. Furthermore, they suggest that an increased regeneration and use of high-quality wood types in tandem with more efficient charcoal production techniques could improve the profitability of the traders. The actors’ margins can also benefit from improved marketing and management skills. Improved profits can, in turn, increase traders’ opportunities to meet SDGs 1, 2, and 4. In addition, improved charcoal quality reduces indoor pollution for end-users, which would bring progress concerning SDG 7.

The increasing charcoal use and other trends in Niger and the region indicate a worsening situation for the forest condition related to deforestation and forest degradation [

19,

22]. Measures that manage to reconcile forest conservation with meeting basic household energy needs are warranted. A transition toward sustainable forest management in Niger and neighboring countries and alternative biomass sources (e.g., through briquetting) could reduce pressure on the region’s forest resources and consequently improve the prospects of reaching SDGs 13 and 15 [

37]. This would probably also promote the conservation of the nation’s scarce forest area. However, due to security problems and the need for regional collaboration, this task appears to be complicated in Niger.

Consequently, concerns could be raised about the future sustainability of the charcoal sector. Previous studies, e.g., [

1,

20], argue that charcoal production is one driver of the forest cover decline in Africa. The increasing charcoal consumption in Niger and expected continued demand in the future may aggravate an unsustainable situation for the forest conditions in the region and the charcoal sector. Therefore, overland charcoal trade flows should be monitored more intensely, specifically along the Sahel region.

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

This study’s findings must be interpreted with caution. Protocols with well-determined sampling probabilities could not be guaranteed since the charcoal trade operates within the informal economy and a sampling frame could not be established. Moreover, interviews in certain cities and towns in Niger and the countryside could not be conducted for security reasons. The lack of standardized and precise records in official statistics and enterprise economic reporting also impacts this study’s reliability. The limited rights for women to engage in business activities, or to speak to strangers, may have affected this study’s outcomes. However, the fact that this study was carried out over several cities in the most populated area of the country could have improved this study’s validity.

Despite the limitations encountered during the survey, this study provides insights into charcoal trade flows and highlights the need for further and in-depth studies about the overland charcoal trade in Africa. Trade streams should be investigated further to capture the actual quantities and actors involved, including production, transport, and trade. The expected increase in charcoal trade calls for regional assessments of its impact on the forests. Studies can also probe more into women’s roles in the charcoal trade in the region. Finally, future research can uncover the real drivers for sustainable charcoal supply chains in Niger.

5. Conclusions

Most of the traded charcoal in the cities in southwestern Niger is imported, to a large extent from Nigeria. Key actors are wholesalers and large-scale and small-scale retailers. This is concluded from the reported origin of the traded charcoal. The business models consider value proposition, value creation, and economic value capture, which differ among enterprise types. Consequently, large-scale traders follow a more focused and professional business strategy than small-scale retailers. Moreover, most actors combine the charcoal trade with the sale of other products, and charcoal surplus is used for basic needs and school fees. This survey study elucidated the supply situation in southern Niger and the origins of the imports from neighboring countries. Business practices can be improved in terms of product quality and the creation of equal opportunities for men and women. There are also compelling reasons to conduct in-depth analyses as to whether the current supply is based on sustainable forest use. A key objective would consist of combining a sound charcoal trade with sustainable sourcing and practices. There are strong motives for implementing regional collaborations to promote a sustainable charcoal sector.

This study is one of the first to examine the charcoal trade in a Sahelian country and to describe business models and strategies. Overland charcoal trade is probably more important than is reflected in the current literature, and it should be regarded as a pan-African challenge; therefore, regional policies may be motivated to avoid leakages, overexploitation, and uncoordinated national policies. The charcoal market and product streams should be monitored more closely and managed appropriately, without adversely affecting low-income households, until charcoal can be supplanted by clean, affordable, adaptable, and sustainable energy sources in Niger.