Sawing Model and Optimization of Single Pass Crosscut Parameters for Pinus kesiya Based on the Transformer Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

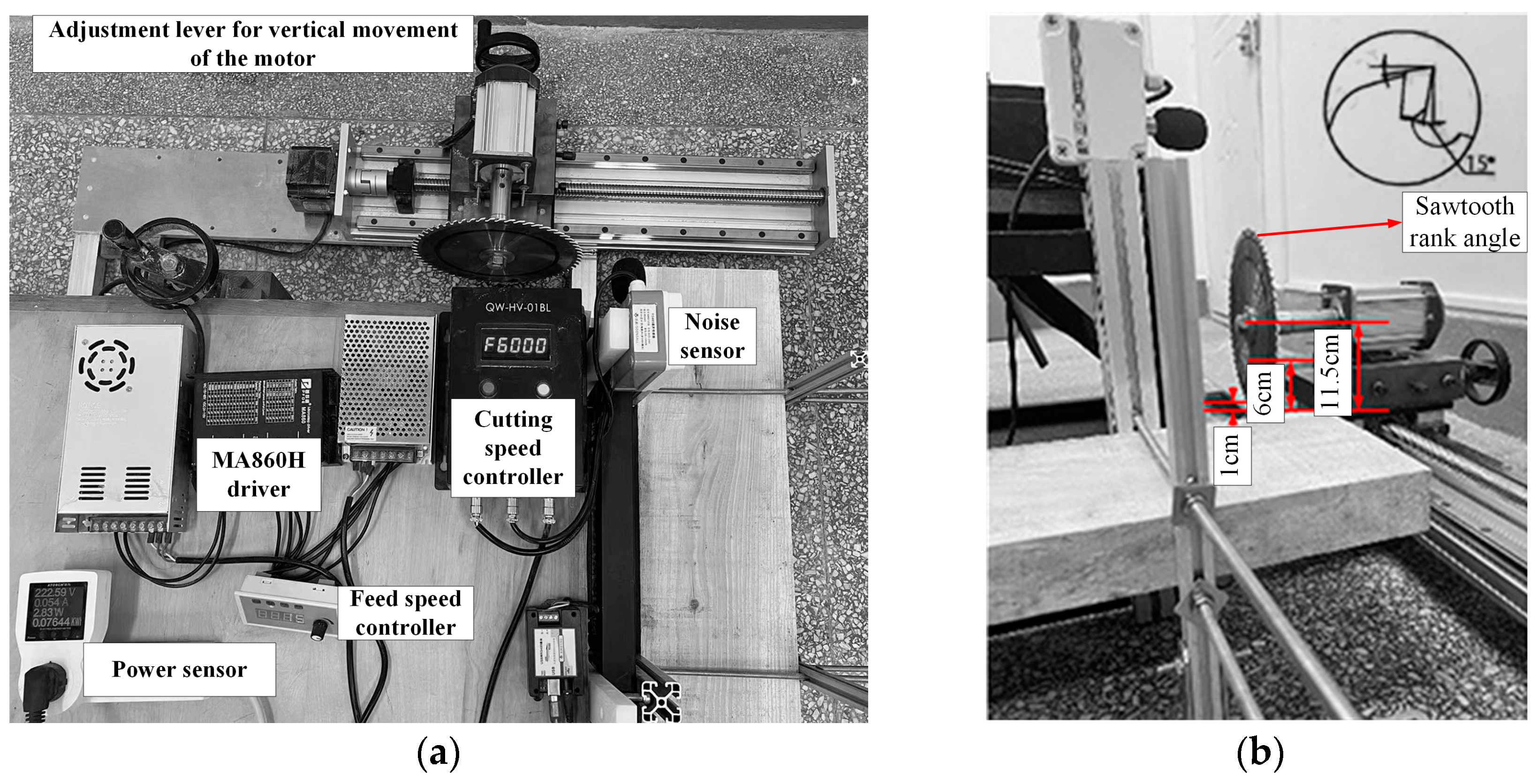

2.2. Experimental Equipment

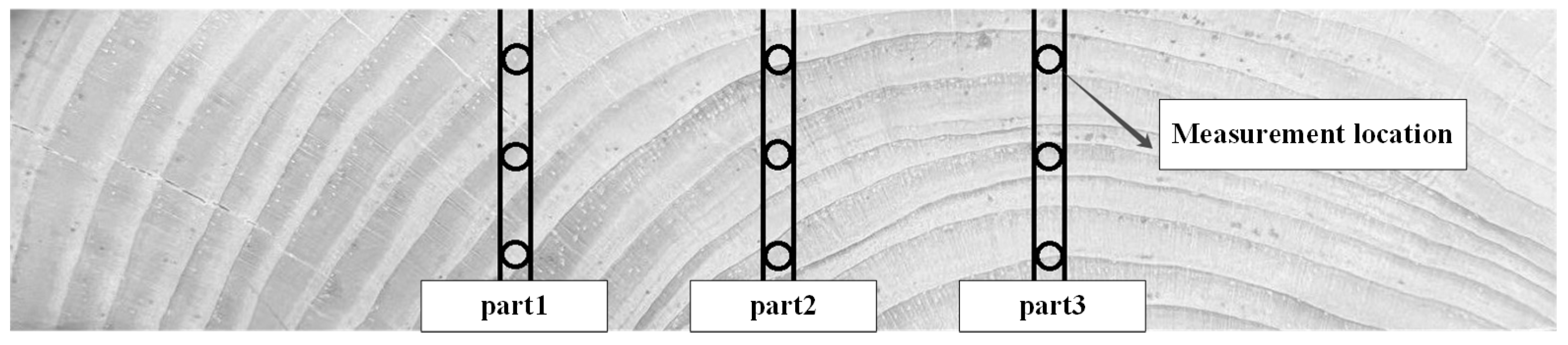

2.3. Data Collection

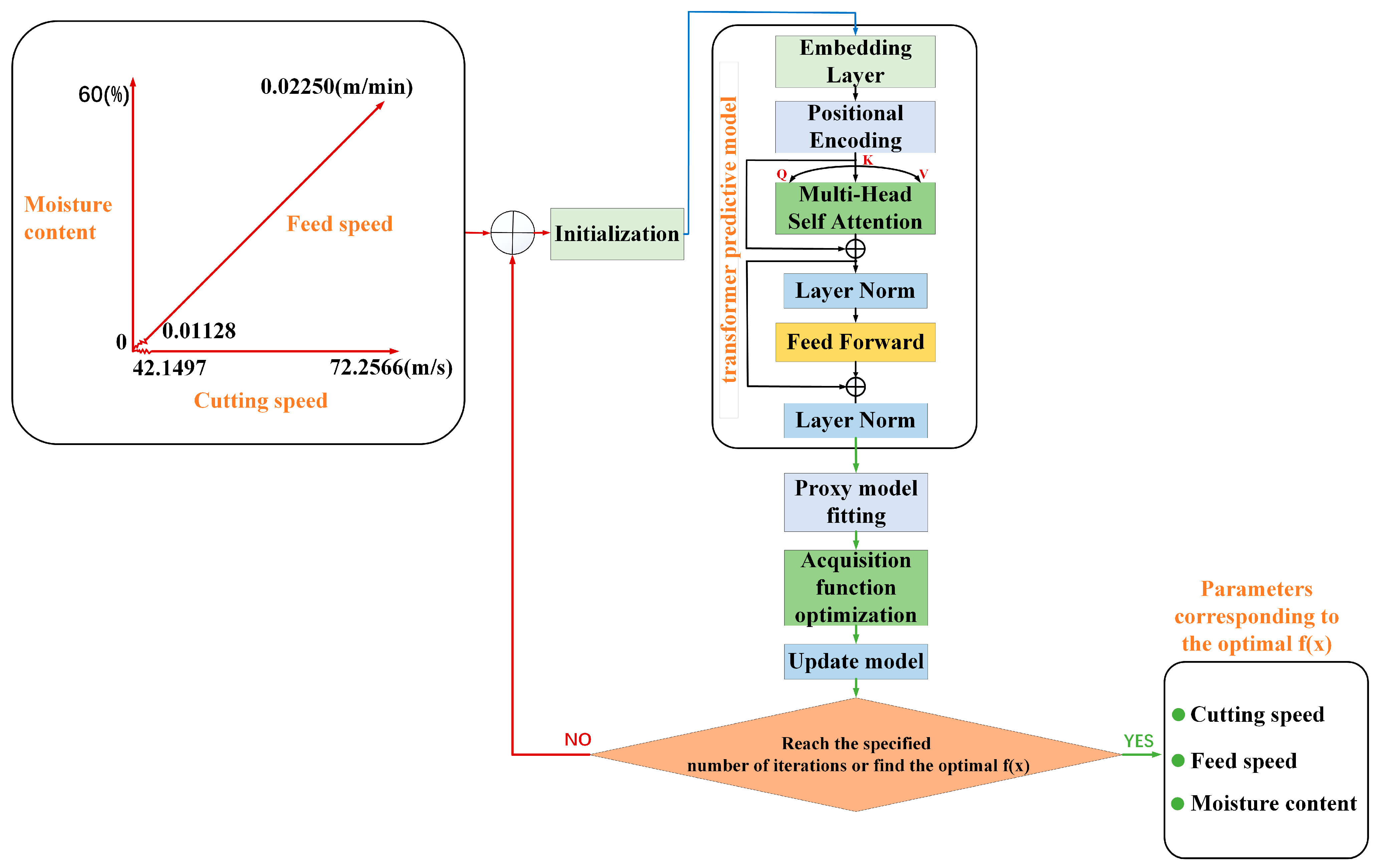

2.4. Model Construction

2.4.1. Sawing Prediction Model

2.4.2. Sawing Optimization Model

2.5. Model Training and Validation

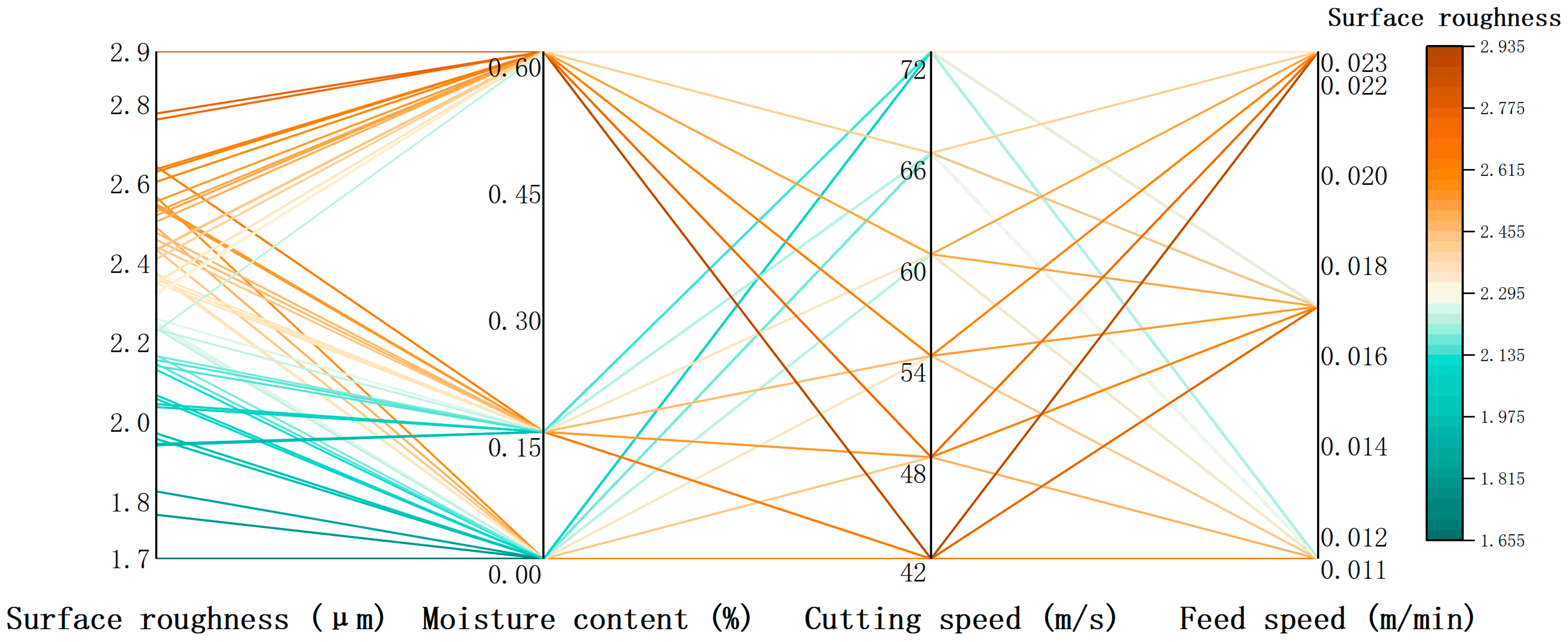

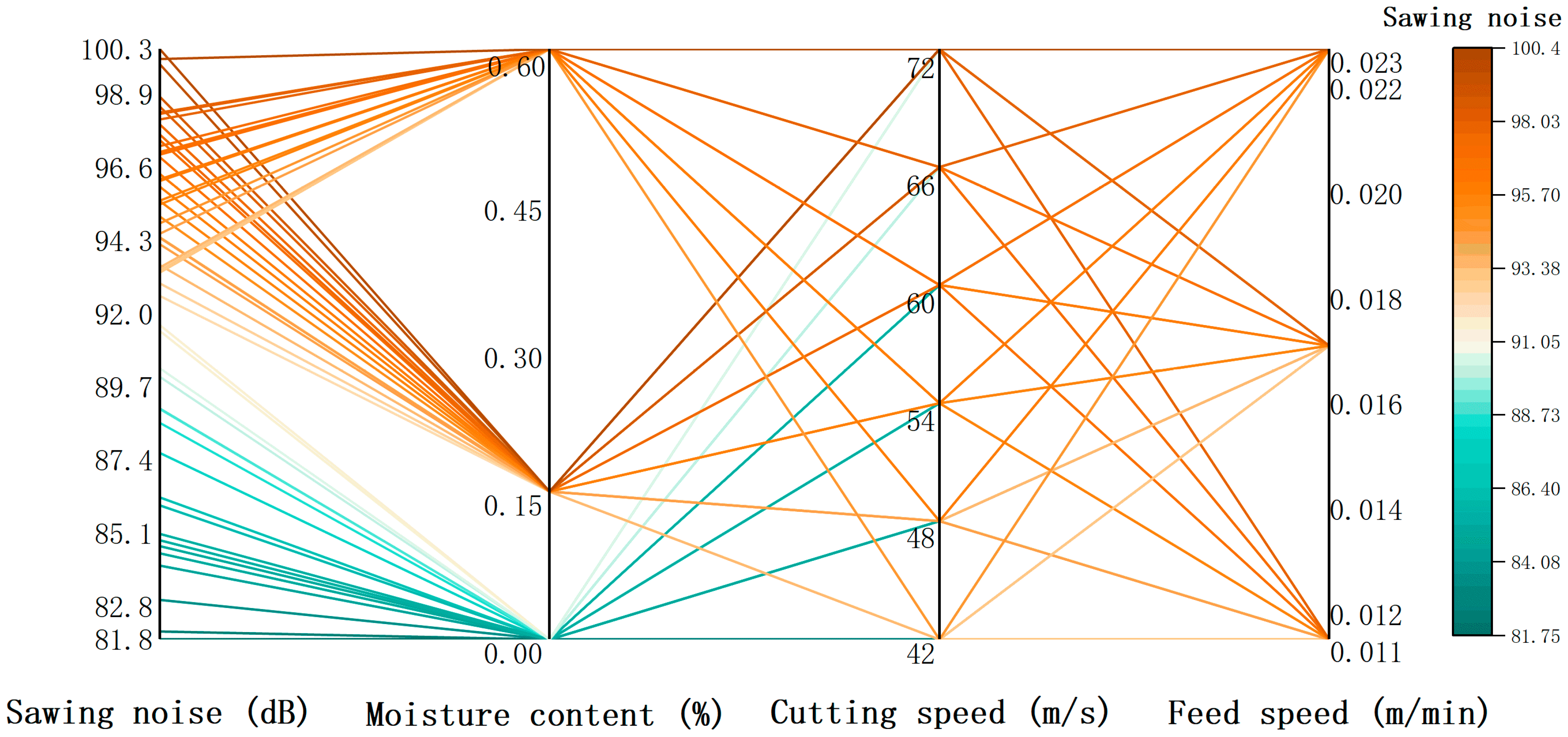

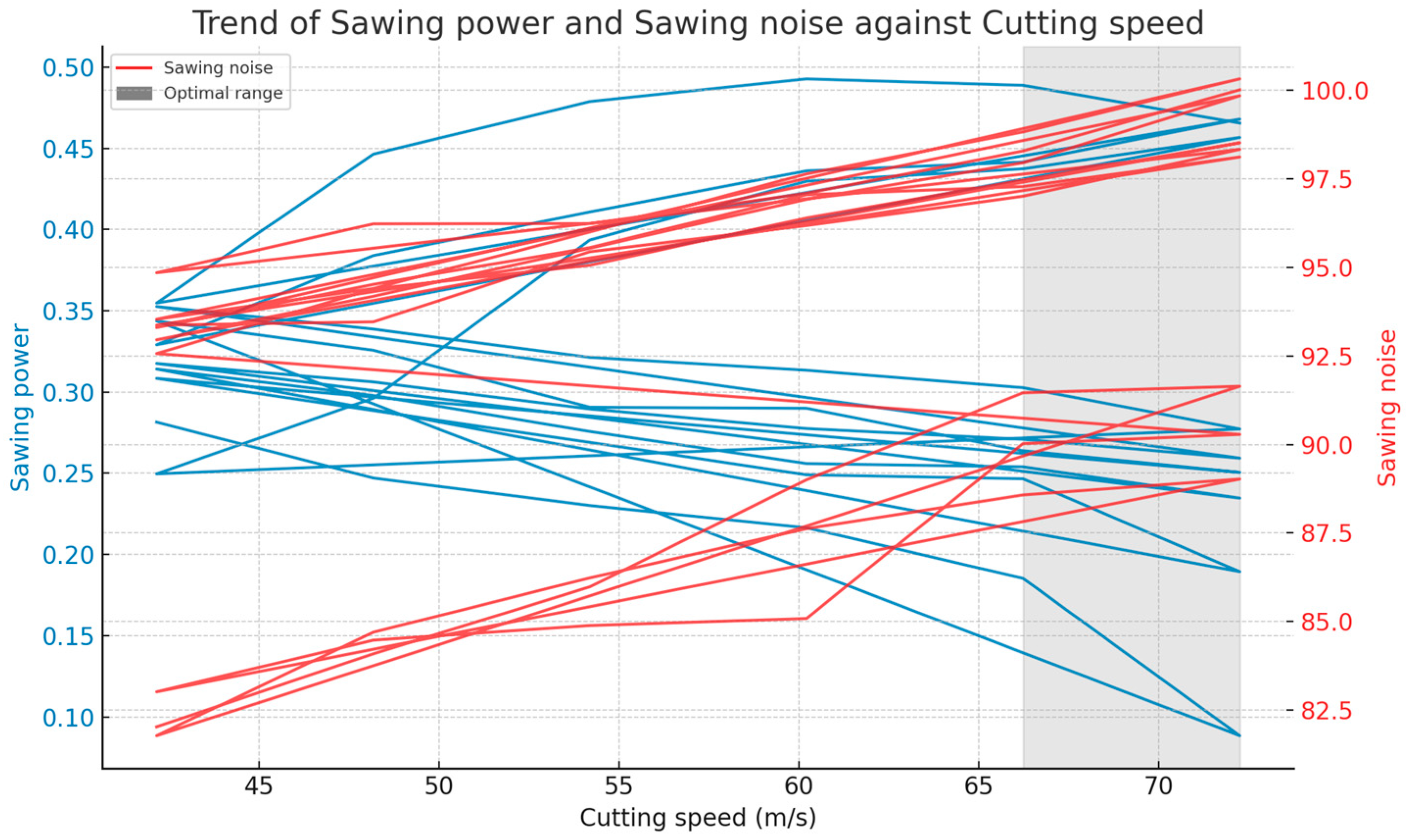

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Experiment Number | Cutting Speed Vc m/s | Feed Speed Vf m/min | Moisture Content WC % | Power Consumption PC kW | Sawing Noise N dB | Surface Quality of Sawn Surfaces Ra μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42.1497 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.281439 | 82.02593 | 2.249926 |

| 2 | 48.1711 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.247065 | 84.09147 | 2.131679 |

| 3 | 54.1925 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.230048 | 85.97955 | 1.957691 |

| 4 | 60.2139 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.216435 | 89.00612 | 1.825889 |

| 5 | 66.2352 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.185284 | 91.46176 | 1.767056 |

| 6 | 72.2566 | 0.01128 | 0 | 0.088432 | 91.64638 | 1.657 |

| 7 | 42.1497 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.343652 | 81.77817 | 2.4895 |

| 8 | 48.1711 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.325642 | 84.6993 | 2.375333 |

| 9 | 54.1925 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.290541 | 86.23342 | 2.243389 |

| 10 | 60.2139 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.289906 | 87.62488 | 2.146667 |

| 11 | 66.2352 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.263774 | 88.57406 | 2.068056 |

| 12 | 72.2566 | 0.01686 | 0 | 0.250518 | 89.02653 | 1.972056 |

| 13 | 42.1497 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.308382 | 83.0181 | 2.566222 |

| 14 | 48.1711 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.288459 | 84.47476 | 2.434222 |

| 15 | 54.1925 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.268968 | 84.88714 | 2.370722 |

| 16 | 60.2139 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.249019 | 85.08683 | 2.235667 |

| 17 | 66.2352 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.246611 | 90.0246 | 2.167611 |

| 18 | 72.2566 | 0.02250 | 0 | 0.189401 | 90.28651 | 2.058889 |

| 19 | 42.1497 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.314071 | 92.56651 | 2.441417 |

| 20 | 48.1711 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.297813 | 94.39432 | 2.367639 |

| 21 | 54.1925 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.275719 | 95.06099 | 2.260194 |

| 22 | 60.2139 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.25589 | 96.39702 | 2.156056 |

| 23 | 66.2352 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.253916 | 97.46135 | 2.045139 |

| 24 | 72.2566 | 0.01128 | 0.15 | 0.23461 | 98.51679 | 1.941972 |

| 25 | 42.1497 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.317478 | 92.95751 | 2.548333 |

| 26 | 48.1711 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.306212 | 94.18668 | 2.459278 |

| 27 | 54.1925 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.28944 | 95.54272 | 2.358389 |

| 28 | 60.2139 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.277496 | 96.92306 | 2.166417 |

| 29 | 66.2352 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.270889 | 97.95669 | 2.038 |

| 30 | 72.2566 | 0.01686 | 0.15 | 0.2592 | 99.8439 | 1.944944 |

| 31 | 42.1497 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.352548 | 93.53476 | 2.643083 |

| 32 | 48.1711 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.338704 | 94.4054 | 2.542028 |

| 33 | 54.1925 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.321248 | 96.00056 | 2.476222 |

| 34 | 60.2139 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.313338 | 97.64016 | 2.349444 |

| 35 | 66.2352 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.302675 | 98.82611 | 2.233056 |

| 36 | 72.2566 | 0.02250 | 0.15 | 0.277223 | 100.3251 | 2.1415 |

| 37 | 42.1497 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.2496 | 2.623444 | 2.605444 |

| 38 | 48.1711 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.296085 | 94.52122 | 2.505222 |

| 39 | 54.1925 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.393518 | 2.442028 | 2.435333 |

| 40 | 60.2139 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.429677 | 97.05276 | 2.352583 |

| 41 | 66.2352 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.437381 | 97.282 | 2.319944 |

| 42 | 72.2566 | 0.01128 | 0.60 | 0.45659 | 98.11916 | 2.228861 |

| 43 | 42.1497 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.329061 | 93.3669 | 2.77725 |

| 44 | 48.1711 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.383951 | 93.46133 | 2.630583 |

| 45 | 54.1925 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.410795 | 95.4466 | 2.555889 |

| 46 | 60.2139 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.436122 | 96.18175 | 2.520639 |

| 47 | 66.2352 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.441544 | 97.01009 | 2.433583 |

| 48 | 72.2566 | 0.01686 | 0.60 | 0.467979 | 98.33269 | 2.325583 |

| 49 | 42.1497 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.354726 | 94.8481 | 2.932611 |

| 50 | 48.1711 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.446331 | 96.22889 | 2.762056 |

| 51 | 54.1925 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.478691 | 96.23643 | 2.637278 |

| 52 | 60.2139 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.492707 | 97.09175 | 2.530167 |

| 53 | 66.2352 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.488713 | 98.28746 | 2.411056 |

| 54 | 72.2566 | 0.02250 | 0.60 | 0.465535 | 100.0133 | 2.351389 |

References

- e Silva, J.C.; Graudal, L. Evaluation of an international series of Pinus kesiya provenance trials for growth and wood quality traits. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 3477–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, K.A.; Ochrymiuk, T.; Hlaskova, L.; Chuchala, D.; Kopecky, Z. Revisiting the estimation of cutting power with different energetic methods while sawing soft and hard woods on the circular sawing machine: A Central European case. Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamiyan, H.; Gholampoor, B.; Tichi, A.H. Effects of Cutting Parameters on the Sound Level and Surface Quality of Sawn Wood. BioResources 2022, 17, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanincová, L.; Procházka, J.; Novák, V.; Kopecký, Z. Influence of moisture content on cutting parameters and fracture characteristics of spruce and Oak wood. Drv. Ind. 2022, 73, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qu, A.; Kan, J.; Kang, F.; Wang, Y. Study of sawing parameters for caragana korshinskii (ck) Branches. Forests 2022, 13, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.F.R.; Melo, L.D.L.; Silva, J.D.; Trugilho, P.F.; Napoli, A. Effect of moisture content on specific cutting energy consumption in Corymbia citriodora and Eucalyptus urophylla woods. Scientia Forestalis 2017, 45, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekiač, J.; Svoreň, J.; Gáborík, J.; Němec, M. Reducing the energy consumption of circular saws in the cutting process of plywood. Coatings 2022, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoreň, J.; Naščák, Ľ.; Barcík, Š.; Koleda, P.; Stehlík, Š. Influence of circular saw blade design on reducing energy consumption of a circular saw in the cutting process. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, E.O.; Demir, A.; Aydın, İ.; Büyüksarı, Ü. Prediction of optimum CNC cutting conditions using artificial neural network models for the best wood surface quality, low energy consumption, and time savings. BioResources 2022, 17, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, A.; Malkocoglu, A.; Ozsahin, S. Optimization of wood machining parameters using artificial neural network in CNC router. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 1728–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásková, L.; Kopecký, Z.; Novák, V. Influence of wood modification on cutting force, specific cutting resistance and fracture parameters during the sawing process using circular sawing machine. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestu, K.T.P.; Nandika, D.; Wahyudi, I.; Usuki, H.; Darmawan, W. Innovation of helical cutting tool edge for eco-friendly milling of wood-based materials. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoyemi, M.J.; Falemara, B.; Owoyemi, A.J. Noise pollution and control in wood mechanical processing wood industries. Preprints 2016. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Roy, R.; Chattopadhyay, A.B. Evaluation of wear of turning carbide inserts using neural networks. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 1996, 36, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cus, F.; Zuperl, U. Approach to optimization of cutting conditions by using artificial neural networks. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 173, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Zhu, C.M.; Wu, Y.Y.; Mura, A. Energy consumption prediction model of SiCp/Al composite in grinding based on PSO-BP neural network. In Solid State Phenomena; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hadad, M.; Attarsharghi, S.; Abyaneh, M.D.; Narimani, P.; Makarian, J.; Saberi, A.; Alinaghizadeh, A. Exploring New Parameters to Advance Surface Roughness Prediction in Grinding Processes for the Enhancement of Automated Machining. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Shang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Cong, R. Prediction Model of Sound Signal in High-Speed Milling of Wood–Plastic Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.; Jena, A.K.; Nayak, J.; Naik, B.; Behera, H.S. A novel PSO based back propagation learning-MLP (PSO-BP-MLP) for classification. In Computational Intelligence in Data Mining-Volume 2: Proceedings of the International Conference on CIDM, 20–21 December 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chenglei, H.; Kangji, L.; Guohai, L.; Lei, P. Forecasting building energy consumption based on hybrid PSO-ANN prediction model. In Proceedings of the 2015 34th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Hangzhou, China, 28–30 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Nielsen, I.E.; Tripathi, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Rasool, G. Transformers in time-series analysis: A tutorial. Circuits Syst Signal Process. 2023, 42, 7433–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.R.; Lee, M. Transformer architecture and attention mechanisms in genome data analysis: A comprehensive review. Biology 2023, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Zhang, T.; Huang, J. Advanced hybrid LSTM-transformer architecture for real-time multi-task prediction in engineering systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jiang, C.; Yu, X.; Fu, R.; Jin, S.; Liu, X. DeepTTA: A transformer-based model for predicting cancer drug response. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.U.; Alsenani, Y.; Zafar, A.; Ullah, K.; Rabie, K.; Shongwe, T. Enhancing heart disease prediction using a self-attention-based transformer model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-K.; Kim, K. A convolutional transformer model for multivariate time series prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 101319–101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teischinger, A.; Avramidis, S.; Hansmann, C. Sawn Timber Steaming and Drying. In Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1167–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Dietsch, P.; Franke, S.; Franke, B.; Gamper, A.; Winter, S. Methods to determine wood moisture content and their applicability in monitoring concepts. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2015, 5, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchala, D.; Orlowski, K.A.; Hiziroglu, S.; Wilmanska, A.; Pradlik, A.; Mietka, K. Analysis of surface roughness of chemically impregnated Scots pine processed using frame-sawing machine. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 18, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.V.; Boardman, C.R.; Thybring, E.E.; Zelinka, S.L. Quantifying and reducing errors in equilibrium moisture content measurements with dynamic vapor sorption (DVS) experiments. Wood Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Cakiroglu, E.O.; Aydin, I. Determination of CNC processing parameters for the best wood surface quality via artificial neural network. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 4768 (1990); Determination of Values of Surface Roughness Parameters Ra, Rz, Rmax Using Electrical Contact (Stylus) Instruments, Concepts and Measuring Conditions. Deutsches Institut für Norming: Berlin, Germany, 1990.

- Licow, R.; Chuchala, D.; Deja, M.; Orlowski, K.A.; Taube, P. Effect of pine impregnation and feed speed on sound level and cutting power in wood sawing. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 272, 122833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Iterations ↓ | R2 ↑ | MSE ↓ | MAE ↓ | RMSE ↓ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer | 298 | Power consumption | 0.880 | 0.135 | 0.273 | 0.367 |

| Sawing noise | 0.953 | 0.034 | 0.107 | 0.184 | ||

| Surface quality of sawn surfaces | 0.977 | 0.059 | 0.177 | 0.243 | ||

| PSO-BP | 3000 | Power consumption | 0.871 | 0.210 | 0.293 | 0.458 |

| Sawing noise | 0.870 | 0.111 | 0.304 | 0.333 | ||

| Surface quality of sawn surfaces | 0.962 | 0.074 | 0.234 | 0.272 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, D. Sawing Model and Optimization of Single Pass Crosscut Parameters for Pinus kesiya Based on the Transformer Model. Forests 2024, 15, 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122144

Wang X, Wang Y, Guo Z, Wang D, Dai Y, Zhao D. Sawing Model and Optimization of Single Pass Crosscut Parameters for Pinus kesiya Based on the Transformer Model. Forests. 2024; 15(12):2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122144

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xingtao, Yuan Wang, Zhichang Guo, Dong Wang, Yang Dai, and Deyong Zhao. 2024. "Sawing Model and Optimization of Single Pass Crosscut Parameters for Pinus kesiya Based on the Transformer Model" Forests 15, no. 12: 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122144

APA StyleWang, X., Wang, Y., Guo, Z., Wang, D., Dai, Y., & Zhao, D. (2024). Sawing Model and Optimization of Single Pass Crosscut Parameters for Pinus kesiya Based on the Transformer Model. Forests, 15(12), 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122144