Tourists’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity, Concession Activity and Recreational Management in Wuyishan National Park in China: A Choice Experiment Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Studies about the Developing Mechanism of National Parks from Policy Dimension

2.2. Studies about the Impact of National Parks’ Infrastructure and Regulations on Tourists’ Participation Willingness

2.3. Studies about the Impacts of National Parks’ Ecological Construction on Tourists’ Participation Willingness

3. Research Methods

3.1. Model Specification

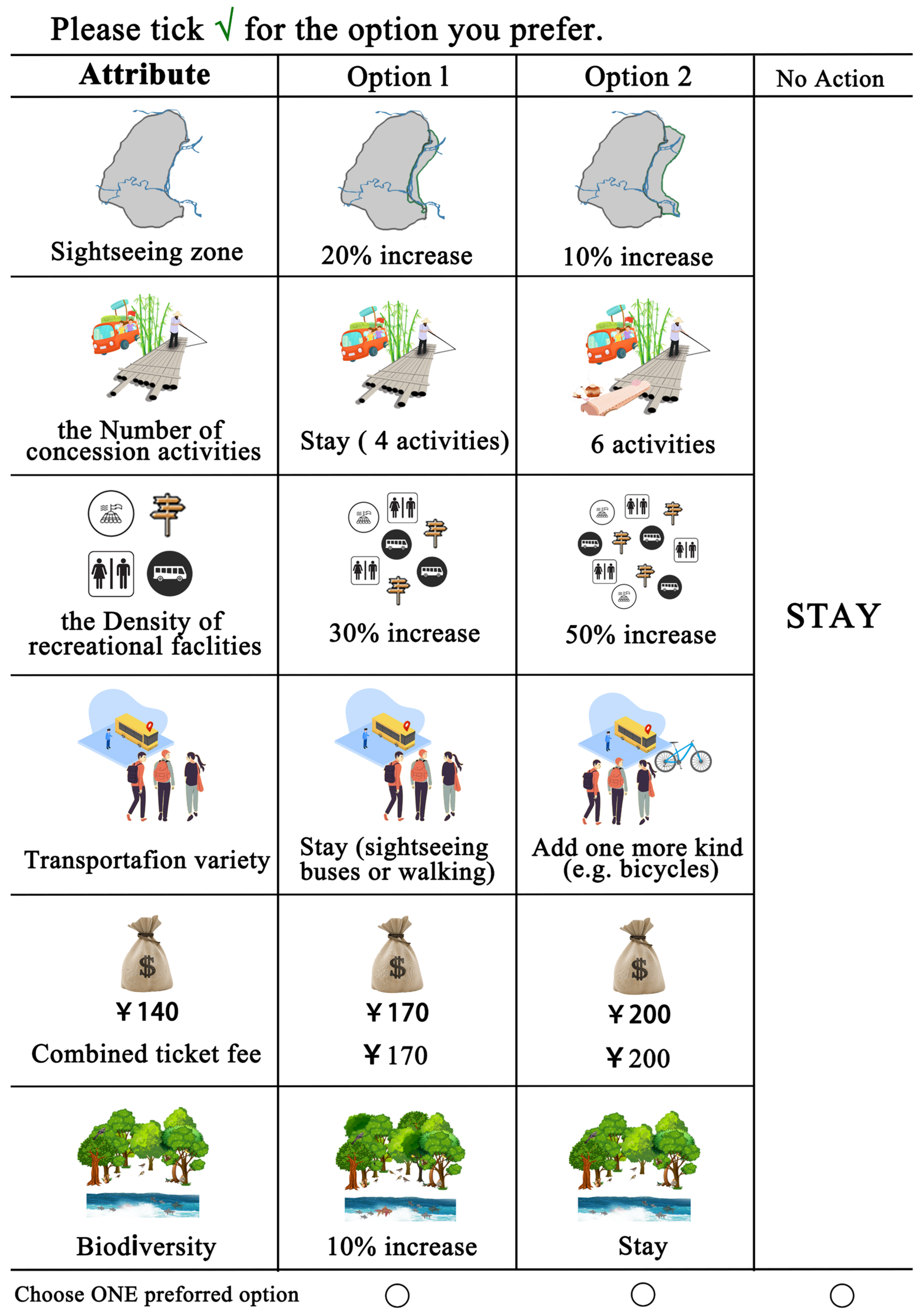

3.2. Choice Experiment Design

3.2.1. Study Range

3.2.2. Key Attributes Description

- (1)

- Sightseeing zone: This refers to the proportion of the park’s open area set by the government, i.e., the proportion of area that can be visited by tourists to the total area of Wuyishan National Park. The higher the ratio, the higher the opening degree of the park. Correspondingly, it is more conducive for tourists to choose different exploration routes according to their different needs. The current ratio of the sightseeing zone that can be visited in Wuyishan National Park is 36.4%. Based on this, the level of this attribute is categorized into three kinds, which are maintaining the status quo, a 10% increase in size and a 20% increase in size.

- (2)

- The number of concession activities: This refers to the concession projects in the park and the featured tourism projects around the park, which are explicitly stipulated in the “Interim Measures for the Administration of Franchised Operations in Wuyishan National Park”. Currently, these include four specific items: bamboo rafting, environmental-friendly sightseeing buses, the Jiuqu River rafting and the cultural performance “Impression Dahongpao”. The number of concession activities reflects the development status of concession operations. A higher number indicates a more thorough utilization of the park’s natural and cultural resources, providing a richer and more fulfilling experience for tourists. The level of this attribute is categorized into three kinds, i.e., four (status quo), six and eight concession activities.

- (1)

- The density of recreational facilities: This refers to the parks’ infrastructure, such as route signage, restrooms and transportation stations. The area of Wuyishan National Park is immense, and the current recreational infrastructure is unable to adequately meet the diverse needs of tourists. The level of this attribute is categorized into three kinds: maintaining the status quo, a 30% increase in density and a 50% increase in density.

- (2)

- Transportation variety: This refers to the means of transportation between attractions or within attractions in Wuyishan National Park. The distance between attractions in the park is relatively long. Since the park is integrated by a number of tourist attractions, there are many and scattered places can be visited within it. At present, walking or taking sightseeing buses (for a fee) are the main ways to visit the park. However, tourists can obtain a better experience and a higher degree freedom while visiting if there are more choices of sightseeing vehicles. Therefore, the level is categorized into two kinds, i.e., maintaining the status quo (sightseeing buses and walking) and adding one more kind of vehicle (e.g., bicycles).

- (3)

- Combined ticket fee: This consists of the admission fee, the sightseeing bus fee and a rafting tour fee. The admission fee is the necessary cost for tourists to enter Wuyishan National Park and is RMB 140 (about USD 19.33) per person. The sightseeing bus fee and the bamboo rafting tour fee for a single day is RMB 75 (about USD 10.36) and RMB 135 (about USD 18.64), respectively. Under normal circumstances, the admission ticket and the sightseeing bus ticket are necessary purchases. After the end of the epidemic in 2023, in order to attract tourists, the park opened up a preferential policy that the year-long admission ticket is free of charge, though the sightseeing bus and the rafting tour ticket need to be purchased separately. The combined ticket fees are set at RMB 140 (about USD 19.33), RMB 170 (about USD 23.47), RMB 200 (about USD 27.62) and RMB 230 (about USD 31.76), respectively.

3.2.3. Choice Set Design

3.2.4. Questionnaire Design

3.2.5. Sampling Design and Data Sources

4. Empirical Model and Result Analyses

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Tourist Choices

4.1.2. Tourist’s Characteristics

4.2. Benchmark Regression Result Analysis

- -

- From the policy dimension:

- -

- From the management dimension:

- -

- From the ecological dimension:

4.3. Tourist Preference Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay Analysis

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biodiversity Science. General plan for establishing national park system. Biodivers. Sci. 2017, 25, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Hou, S. The Character of National Park Franchise. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 182–186+192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwirplies, C.; Dütschke, E.; Schleich, J.; Ziegler, A. The Willingness to Offset CO2 Emissions from Traveling: Findings from Discrete Choice Experiments with Different Framings. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 165, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; He, C. Analysis of Farmers’ Preference for the Transfer of Forest Rights Based on the Selective Experiment Method. J. Beijing For. Univ. Sci. 2019, 18, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valck, J.; Vlaeminck, P.; Broekx, S.; Liekens, I.; Aertsens, J.; Chen, W.; Vranken, L. Benefits of Clearing Forest Plantations to Restore Nature? Evidence from a Discrete Choice Experiment in Flanders, Belgium. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Burton, M.; Zhang, A. Estimation of farmland eco-compensation criteria based on latent class model:a case of a discrete choice experiment. China Popul. Environ. 2016, 26, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, M.; Liao, B.; Cai, S.; Lu, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yang, J. Analysis of the Preference and Heterogeneity in Postoperative Follow-up Care for Breast Cancer Patients—Based on Discrete Choice Experiment. Mil. Nurs. 2023, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, M.Y.; Sofi, A.A. Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity Conservation in Dachigam National Park, India. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 62, 126022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardanoni, V.; Guerriero, C. Young People’ s Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 179, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Ni, Q.; Qiao, D.; Yao, L.; Zhao, M. Distance effect on the willingness of rural residents to participate in watershed ecological restoration:Evidence from the Shiyang River Basin. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Salm, J.A.P.; Bočkarjova, M.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Runhaar, H.A.C. Citizens’ Preferences and Valuation of Urban Nature: Insights from Two Choice Experiments. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 208, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, Y. Analysis of Beijing citizens’ demand for urban green space based on choice experiment method. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Sun, H.; Ali, M.A.S.; Mao, H. Exploring Public Preferences for Ecosystem Service Improvements Regarding Nature Reserve Restoration: A Choice Experiment Study. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzek, T.; Samdin, Z.; Mohamad, W.N. Assessing Visitors’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for the Malayan Tiger Conservation in a Malaysian National Park: A Choice Experiment Method. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 191, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Huang, Q.; Lin, X.; Chen, R.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q. Evaluation of Recreation Resources Value in Fujian Wetland Nature Reserves—Using Choice Experiment Method. For. Econ. 2020, 42, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Juutinen, A.; Mitani, Y.; Mäntymaa, E.; Shoji, Y.; Siikamäki, P.; Svento, R. Combining Ecological and Recreational Aspects in National Park Management: A Choice Experiment Application. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, Q. Research on Tourists’ Preference and Willingness to Pay for Recreational Attributes of National Parks in the Post-epidemic Era—EmpiricalAnalysis Based on the Choice Experiment Method. China For. Econ. 2022, 5, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Cao, A.; Chen, W.; Yan, S. Welfare Value and Heterogeneity: An Experimental Analysis of Tourists’ Choice in Wuyi Mountain National Park. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2022, 38, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Ma, Y.; Huang, K.; Su, L.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, D.; Wang, Y. Strategic Approach on Promoting Reform of China’s Natural Protected Areas System with National Parks as Backbone. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2018, 33, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Sheng, M. Thoughts and Suggestions on the Establishment of Nature Reserve System with National Park as the Main Body. Ecol. Sci. 2022, 41, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Conservation first, national representative, and commonwealth:the three concepts of China’s National Park System Construction. Biodivers. Sci. 2017, 25, 1040–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, F.; Tian, Y.; Jin, K. On implementation path of the strictest conservation policies in national park management. Biodivers. Sci. 2021, 29, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Fang, Z. Ecological Political Philosophy in National Parks Management: An Analysis of the Quasi-public Goods Attributes of National Parks. J. Southeast Univ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 21, 118–124+147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Huang, M. The Construction of Eco-Compensation Mechanisms of National Parks under the Systematic View. Nat. Resour. Econ. China 2024, 37, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Liu, X. Ecological Products Value Realization Mechanism Based on Stakeholder Theory:A Case Study of Wuyishan National Park in China. World For. Res. 2023, 36, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Su, Y. National parks are not tourist attractions, but national park tourism should be developed. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Su, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Xu, W.; Min, Q.; Zhang, H. Theoretical debates and innovative practices of the development of China’s nature protected area under the background of ecological civilization construction. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. The Comparison and Construction of Concession Management Mechanism in China National Parks. Tour. Forum 2023, 16, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.; Wilson, C.; Quayle, A.; Managi, S.; Khanal, U. Can a Tourist Levy Protect National Park Resources and Compensate for Wildlife Crop Damage? An Empirical Investigation. Environ. Dev. 2022, 42, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Ao, C.; Ning, J.; Gao, Q. Public Preference Heterogeneity for Wetland Ecosystem Services Based on a Latent Class Model. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 747–760. [Google Scholar]

- Chaminuka, P.; Groeneveld, R.A.; Selomane, A.O.; Van Ierland, E.C. Tourist Preferences for Ecotourism in Rural Communities Adjacent to Kruger National Park: A Choice Experiment Approach. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Wei, H.; Zhou, Y. Study on Valuing Recreation-Related Environmental Attributes of The National Forest Park Bace on CEM. China Popul. Environ. 2013, 23, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; An, K. Evaluation of tourism environmental carrying capacity of bathing beaches based on choice experiment. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 44, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ao, C.; Mao, B.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, B.; Ma, J. Trade-offs between ecological and recreational attributes in nature reserve management: An application of choice experiment. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 3944–3954. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, T. Natural Attributes or Aesthetic Attributes: Which Is More Valuable in Recreational Ecosystem Services of Nature-Based Parks Considering Tourists’ Environmental Knowledge and Attitude Impacts? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 44, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Wei, W.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Q. Studying Recreational Resources of Forest Park in Fujian Based on Choice Experiment Method. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z. Agritourism in the View of Tourism Anthropology. J. Guangxi Minzu Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2005, 27, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Rong, H. Satisfaction Evaluation of Tourist and Influence Factors Analysis in Rural Tourism. Bus. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Yang, H.; He, Q. On the Construction of Tourist Satisfaction Evaluation System and lts Empirical Study. Tour. Trib. 2012, 27, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kularatne, T.; Wilson, C.; Lee, B.; Hoang, V.-N. Tourists’ before and after Experience Valuations: A Unique Choice Experiment with Policy Implications for the Nature-Based Tourism Industry. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 69, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, L.; Cai, L.; Yang, Z. Tourist Perceived Value of Wetlang Park:Evidence from Xixi and Qinhu Lake. Tour. Trib. 2014, 29, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.P.; Smith, B. The Destination Product and Its Impact on Traveller Perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemunto, M.; Kamau, G. Willingness to Pay for Nairobi National Park: An Application of Discrete Choice Experiment. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J.; Tsushima, T. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Farmers’ Preferences forAgro-ecological Protection Policy Goals and Their Participation Behaviors: Evidence from Choice Experimental Analysis of Farmers from Ten Districts (Counties) in Chongqing. China Rural Surv. 2021, 1, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Liu, W.; Gao, Z. Selection Preference and Preference Heterogeneity of Smallholders’ Participation in Agricultural Industrial Chain: An Analysis Based on the Choice Experiment Method. China Rural Surv. 2020, 2, 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.R. Hensher, D.A., Rose, J.M., & Greene, W.H. (2005). Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 742+xxiv Pp. US$60.00. ISBN: 0-521-60577-6. Psychometrika 2007, 72, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ge, J.; Gong, J. Study on the lnfluencing Mechanism of Tourists’ Revisit Intention in National Parks—A Case Study of Shennongjia National Park. For. Econ. 2022, 44, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.; Andrews, C.; Orenstein, D.E.; Teff-Seker, Y.; Zulian, G. A Mixed-Methods Approach to Analyse Recreational Values and Implications for Management of Protected Areas: A Case Study of Cairngorms National Park, UK. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 56, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etongo, D.; Lafleur, H.; Vel, T. Community Perceptions and Attitudes towards the Management of Protected Areas in Seychelles with Morne Seychellois National Park as Case Study. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H. Development Challenges and Management Strategies on the Kenyan National Park System: A Case of Nairobi National Park. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2022, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Key Attributes | Attributes Level |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | Sightseeing zone | 0 = Stay 1 = 10% increase 2 = 20% increase |

| Number of concession activities | 0 = 4 1 = 6 2 = 8 | |

| Management | Density of recreational facilities | 0 = Stay 1 = 30% increase 2 = 50% increase |

| Transportation variety | 0 = Stay (sightseeing buses or walking) 1 = Add one more kind (e.g., bicycles) | |

| Combined ticket fee | RMB 140 (about USD 19.33) RMB 170 (about USD 23.47) RMB 200 (about USD 27.62) RMB 230 (about USD 31.76) | |

| Ecology | Biodiversity | 0 = Stay 1 = 10% increase 2 = 20% increase |

| Variable | Variable Description and Assignment |

|---|---|

| Gender | 1 = Male; 0 = Female |

| Age | 1 = Under 18; 2 = 19–35; 3 = 36–60; 4 = Over 60 |

| Education | 1 = Junior high school and below; 2 = Senior school or vocational high school; 3 = Specialized training school; 4 = Undergraduate: 5 = Master or above |

| Travel distance | Travel time from the city of residence to Wuyishan: 1 = 1–4 h; 2 = 5–8 h; 3 = 9–12 h; 4 = 13 h or above |

| Monthly income | 1 = RMB 3000 (about USD 414.23) and below; 2 = RMB 3000 (about USD 414.23) − RMB 7000 (about USD 966.54); 3 = RMB 7000 (about USD 966.54) − RMB 11000 (about USD 1518.85); 4 = RMB 11000 (about USD 1518.85) − RMB 15000 (about USD 2071.17); 5 = RMB 15000 (about USD 2071.17) or above |

| Available time | Free time available to tourists during the year (Compared with the statutory and weekend holidays): 1 = Less than it; 2 = Equivalent to it; 3 = More than it |

| Knowledge about the park | Tourists’ knowledge about the concept, policy and status of national parks: 1 = Not know with not aware; 2 = Much less known with of slightly aware; 3 = Less known with moderately aware; 4 = Known with aware; 5 = Very familiar |

| Willingness to revisit | 1 = Yes; 0 = No |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sightseeing zone | 1740 | 0.866 | 0.785 | 0 | 2 |

| The number of concession activities | 1740 | 0.974 | 0.824 | 0 | 2 |

| The density of recreational facilities | 1740 | 0.997 | 0.773 | 0 | 2 |

| Transportation variety | 1740 | 0.543 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Combined ticket fee | 1740 | 0.913 | 0.809 | 0 | 2 |

| Biodiversity | 1740 | 1.472 | 1.181 | 0 | 3 |

| Variable | Samples | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 435 | 1.505 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 435 | 2.268 | 0.598 | 1 | 4 |

| Education | 435 | 3.763 | 0.941 | 1 | 5 |

| Travel distance | 435 | 1.578 | 0.786 | 1 | 4 |

| Monthly income | 435 | 2.768 | 1.311 | 1 | 5 |

| Available time | 435 | 2.422 | 0.690 | 1 | 3 |

| Knowledge about the park | 435 | 3.242 | 1.088 | 1 | 5 |

| Willingness to revisit | 435 | 1.151 | 0.359 | 1 | 2 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLM | MLM | MLM | |

| Attributes | |||

| Fixed variable | |||

| Density of recreational facilities | 0.570 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.510 *** |

| (0.052) | (0.143) | (0.165) | |

| Combined ticket fee | −0.003 * | −0.013 ** | −0.016 ** |

| (0.045) | (0.154) | (0.191) | |

| Biodiversity | 0.398 *** | 0.284 ** | 0.337 ** |

| (0.049) | (0.127) | (0.154) | |

| Random variable | |||

| Sightseeing zone | 0.418 *** | 0.265 * | 0.326 * |

| (0.062) | (0.157) | (0.192) | |

| Transportation variety | 0.698 *** | 0.552 ** | 0.675 ** |

| (0.107) | (0.237) | (0.296) | |

| Number of concession activities | 0.618 *** | 0.636 *** | 0.784 *** |

| (0.051) | (0.216) | (0.278) | |

| Random parameter standard deviation | |||

| Sightseeing zone | 1.048 ** | 1.154 *** | |

| (0.446) | (0.426) | ||

| Transportation variety | 3.138 ** | 4.159 *** | |

| (1.244) | (1.561) | ||

| Number of concession activities | 1.119 *** | 1.332 *** | |

| (0.434) | (0.513) | ||

| Social and economic characteristic | |||

| Gender | 0.388 | ||

| (0.653) | |||

| Age | −0.777 * | ||

| (0.403) | |||

| Education | 0.777 ** | ||

| (0.338) | |||

| Travel distance | 0.131 | ||

| (0.404) | |||

| Monthly income | 0.010 | ||

| (0.288) | |||

| Available time | 0.976 | ||

| (0.622) | |||

| Knowledge about the park | −0.489 | ||

| (0.414) | |||

| Willingness to revisit | 1.858 ** | ||

| (0.796) | |||

| Constant term | |||

| ASC | 3.026 *** | 3.368 * | |

| (0.488) | (1.885) | ||

| Number of obs | 5220.000 | 5220.000 | 5220.000 |

| Likelihood | −2098.093 | −1300.2155 | −1283.4994 |

| Variable | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| MLM | MLM | MLM | |

| Attributes | |||

| Fixed variable | |||

| Density of recreational facilities | 0.493 *** | 0.423 *** | 0.452 *** |

| (0.164) | (0.148) | (0.156) | |

| Combined ticket fee | −0.015 ** | −0.013 ** | −0.014 ** |

| (0.182) | (0.160) | (0.173) | |

| Biodiversity | 0.337 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.311 ** |

| (0.143) | (0.131) | (0.137) | |

| Random variable | |||

| Sightseeing zone | −0.302 | 0.278 * | 0.303 * |

| (0.706) | (0.164) | (0.177) | |

| Transportation variety | 0.669 ** | −0.366 | 0.596 ** |

| (0.287) | (0.868) | (0.262) | |

| Number of concession activities | 0.769 *** | 0.648 *** | 2.159 *** |

| (0.251) | (0.225) | (0.801) | |

| Random parameter standard deviation | |||

| Sightseeing zone | 1.010 *** | 1.036 ** | 1.120 ** |

| (0.386) | (0.453) | (0.435) | |

| Transportation variety | 4.140 *** | 3.235 ** | 3.543 ** |

| (1.554) | (1.314) | (1.480) | |

| Number of concession activities | 1.245 *** | 1.097 ** | 1.050 ** |

| (0.423) | (0.435) | (0.419) | |

| Cross term | |||

| Sightseeing zone × Age | 0.060 | ||

| (0.194) | |||

| Sightseeing zone × Education | 0.303 * | ||

| (0.165) | |||

| Sightseeing zone × Willingness to revisit | 0.559 | ||

| (0.361) | |||

| Transportation variety × Age | −0.133 | ||

| (0.251) | |||

| Transportation variety × Education | 0.032 | ||

| (0.163) | |||

| Transportation variety × Willingness to revisit | 0.964 * | ||

| (0.558) | |||

| Number of concession activities × Age | −0.382 * | ||

| (0.200) | |||

| Number of concession activities × Education | 0.020 | ||

| (0.116) | |||

| Number of concession activities × Willingness to revisit | 0.589 * | ||

| (0.321) | |||

| Constant term | |||

| ASC | 3.366 *** | 3.271 *** | 3.310 *** |

| (0.516) | (0.500) | (0.505) | |

| Number of obs | 5220.000 | 5220.000 | 5220.000 |

| Likelihood | −1293.2583 | −1296.3805 | −1294.2249 |

| Key Attributes | Willingness to Pay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | |

| Density of recreational facilities | 32.15 *** | 31.86 *** | 32.87 *** | 32.54 *** | 32.29 *** |

| Biodiversity | 21.85 ** | 21.07 ** | 22.47 ** | 22.38 ** | 22.21 ** |

| Sightseeing zone | 20.38 * | 20.38 * | 0 (−20.01) | 21.38 * | 21.64 * |

| Transportation variety | 42.46 ** | 42.19 ** | 44.60 ** | 0 (−28.15) | 42.57 ** |

| Number of concession activities | 48.92 *** | 49.01 *** | 51.27 ** | 49.85 ** | 154.21 ** |

| Total (RMB) | 165.76 (about USD 22.98) | 164.51 (about USD 22.75) | 151.21 (about USD 20.97) | 136.15 (about USD 18.88) | 272.92 (about USD 37.85) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Jin, D. Tourists’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity, Concession Activity and Recreational Management in Wuyishan National Park in China: A Choice Experiment Method. Forests 2024, 15, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15040629

Liu J, Wu Y, Jiang X, Jin D. Tourists’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity, Concession Activity and Recreational Management in Wuyishan National Park in China: A Choice Experiment Method. Forests. 2024; 15(4):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15040629

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiayu, Yining Wu, Xuemei Jiang, and Dian Jin. 2024. "Tourists’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity, Concession Activity and Recreational Management in Wuyishan National Park in China: A Choice Experiment Method" Forests 15, no. 4: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15040629

APA StyleLiu, J., Wu, Y., Jiang, X., & Jin, D. (2024). Tourists’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity, Concession Activity and Recreational Management in Wuyishan National Park in China: A Choice Experiment Method. Forests, 15(4), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15040629